Chapter 42 Feeding Healthy Infants, Children, and Adolescents

Feeding During the First Year of Life

Breast-feeding

Feedings should be initiated soon after birth unless medical conditions preclude them. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and World Health Organization (WHO) strongly advocate breast-feeding as the preferred feeding for all infants. The success of breast-feeding initiation and continuation depends on multiple factors, such as education about breast-feeding, hospital breast-feeding practices and policies, routine and timely follow-up care, and family and societal support (Table 42-1). The AAP recommends exclusive breast-feeding for a minimum of 4 mo and preferably for 6 mo. The advantages of breast-feeding are well documented (Tables 42-2 and 42-3), and contraindications are rare (Table 42-4).

Table 42-1 STEPS TO ENCOURAGE BREAST-FEEDING IN THE HOSPITAL: UNICEF/WHO BABY-FRIENDLY

HOSPITAL INITIATIVES

MOTHERS TO LEARN

ADDITIONAL INSTRUCTIONS

UNICEF, United Nations Children’s Fund; WHO, World Health Organization.

Table 42-2 SELECTED BENEFICIAL PROPERTIES OF HUMAN MILK COMPARED TO INFANT FORMULA

| Secretory lgA | Specific antigen-targeted anti-infective action |

| Lactoferrin | Immunomodulation, iron chelation, antimicrobial action, antiadhesive, trophic for intestinal growth |

| κ-casein | Antiadhesive, bacterial flora |

| Oligosaccharides | Prevention of bacterial attachment |

| Cytokines | Anti-inflammatory, epithelial barrier function |

| Growth factors | |

| Epidermal growth factor | Luminal surveillance, repair of intestine |

| Transforming growth factor (TGF) | |

Table 42-3 CONDITIONS FOR WHICH HUMAN MILK HAS BEEN SUGGESTED TO HAVE A PROTECTIVE EFFECT

Adapted from the Schanler RJ, Dooley S: Breastfeeding handbook for physicians, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2006, American Academy of Pediatrics.

Table 42-4 ABSOLUTE AND RELATIVE CONTRAINDICATIONS TO BREAST-FEEDING DUE TO MATERNAL HEALTH CONDITIONS

| MATERNAL HEALTH CONDITIONS | DEGREE OF RISK |

|---|---|

| HIV and HTLV infection |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; HbsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HTLV, human T-lymphotropic virus.

Mothers should be encouraged to nurse at each breast at each feeding starting with the breast offered 2nd at the last feeding. It is not unusual for an infant to fall asleep after the 1st breast and refuse the 2nd. It is preferable to empty the 1st breast before offering the 2nd in order to allow complete emptying and therefore better milk production. Table 42-5 summarizes patterns of milk supply in the 1st week.

Table 42-5 PATTERNS OF MILK SUPPLY

| DAY OF LIFE | MILK SUPPLY |

|---|---|

| Day 1 | Some milk (~5 mL) may be expressed |

| Days 2-4 | Lactogenesis, milk production increases |

| Day 5 | Milk present, fullness, leaking felt |

| Day 6 onward | Breasts should feel “empty” after feeding |

Adapted from Neifert MR: Clinical aspects of lactation: promoting breastfeeding success, Clin Perinatol 26:281–306, 1999.

Jaundice

Breast-feeding jaundice is a common reason for hospital readmission of healthy breast-fed infants and is largely related to insufficient fluid intake (Chapter 96.3). It may also be associated with dehydration and hypernatremia. Breast milk jaundice causes persistently high serum indirect bilirubin in a thriving healthy baby. Jaundice generally declines in the 2nd wk of life. Infants with severe or persistent jaundice should be evaluated for problems such as galactosemia, hypothyroidism, urinary tract infection, and hemolysis before ascribing the jaundice to breast milk that might contain inhibitors of glucuronyl transferase or enhanced absorption of bilirubin from the gut. Persistently high bilirubin can require changing from breast milk to infant formula for 24-48 hr and/or phototherapy without cessation of breast-feeding. Breast-feeding should resume after the decline in serum bilirubin. Parents should be reassured and encouraged to continue collecting breast milk during the period when the infant is taking formula.

Growth of the Breast-fed Infant

The rate of weight gain of the breast-fed infant differs from that of the formula-fed infant, and the infant’s risk for excess weight gain during late infancy may be associated with bottle feeding. Some of the differences in weight gain are explained by the use of growth charts derived from predominantly formula-fed children, and several studies suggest that the growth pattern of the population of breast-fed infants should be considered the norm. The WHO, has published a growth reference based on the growth of healthy breast-fed infants through the 1st yr of life. The new standards (http://www.who.int/childgrowth) are the result of a study in which >8,000 children were selected from 6 countries. The infants were selected based on healthy feeding practices (breast-feeding), good health care, high socioeconomic status, and nonsmoking mothers, so that they reflect the growth of breast-fed infants in the optimal conditions and can be used as prescriptive rather than normative curves. Charts are available for growth monitoring from birth to age 6 yr. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends use of these charts for infants 0 to 23 months of age.

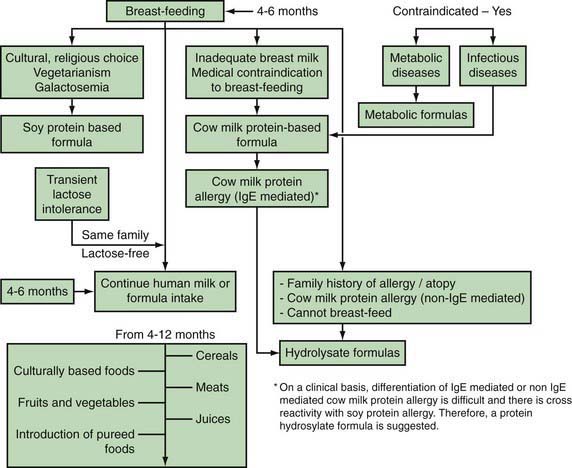

Formula Feeding (Fig. 42-1)

Most women make their feeding choices for their infant early in pregnancy. In a U.S. survey, although 83% of respondents initiated breast-feeding, the percentage who continued to breast-feed declined to 50% at 6 mo. Fifty-two percent of infants received formula while in the hospital and by 4 mo 40% had consumed other foods as well. Despite efforts to promote breast-feeding and discourage complementary foods before 4 mo of age, supplementing breast-feeding with infant formula and early introduction of complementary foods remain common in the USA. Indications for the use of infant formula are as a substitute or a supplement for breast milk or as a substitute for breast milk when breast milk is medically contraindicated by maternal (see Table 42-4) or infant factors.

Figure 42-1 Feeding algorithm for term infants.

(From Gamble Y, Bunyapen C, Bhatia J: Feeding the term infant. In Berdanier CD, Dwyer J, Feldman EB, editors: Handbook of nutrition and food, Boca Raton, FL, 2008, CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, pp 271–284, Fig. 15-3.)

Complementary Feeding

The timely introduction of complementary foods (all solid foods and liquid foods other than breast milk or formula, also called weaning foods or beikost) during infancy is necessary to enable transition from milk feedings to other foods and is important for nutritional and developmental reasons (Table 42-6). The dilemmas of the weaning period are different in different societies. The ability of exclusive breast-feeding to meet macronutrient and micronutrient requirements becomes limiting with increasing age of the infant. Current WHO recommendations on the age at which complementary food should be introduced are based on the optimal duration of exclusive breast-feeding. A WHO-commissioned systematic review of the optimal duration of exclusive breast-feeding compared outcomes with exclusive breast-feeding for 6 vs 3-4 mo. The review concluded that there were no differences in growth between the 2 durations of exclusive breast-feeding. Another systematic review concluded that there was no compelling evidence to change the recommendations for starting complementary foods at 4-6 mo. The AAP Pediatric Nutrition Handbook also states that there is no significant harm associated with introduction of complementary foods at 4 mo of age and no significant benefit from exclusive breast-feeding for 6 mo in terms of growth, zinc and iron nutriture, allergy, or infections. The European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition considers that exclusive breast-feeding for ~6 mo is desirable, but that the introduction of complementary foods should not occur before 17 weeks (~4 mo) and should not be delayed beyond 26 weeks (~6 mo).

Feeding Toddlers and Preschool-Age Children

Feeding Practices

The period starting after 6 mo until 15 mo is characterized by the acquisition of self-feeding skills because the infant can grasp finger foods, learn to use a spoon, and eat soft foods (Table 42-7). Around 15 mo, the child learns to feed himself or herself and to drink from a cup, messy as that may be. Infants may still breast-feed or desire formula bottle feeding, but bedtime bottles should be discouraged because of the association with dental caries. Even breast-fed babies can develop caries; therefore, drinking juices and other sugared drinks from a bottle should be discouraged in all infants at all times. In the 2nd yr of life, self-feeding becomes a norm and provides the opportunity for the family to eat together with less stress. Self-feeding allows the child to limit his or her intake while also observing parental reactions to the child’s eating behavior. Encouraging positive eating behaviors and ignoring negative ones unless they jeopardize the health and safety of the infant should be the family’s goal.

| AGE (mo) | FEEDING/ORAL SENSORIMOTOR |

|---|---|

| Birth to 4-6 |

Modified from Udall Jr JN: Infant feeding: initiation, problems, approaches, Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 37:369–408, 2007.

Feeding School-Age Children and Adolescents

MyPyramid

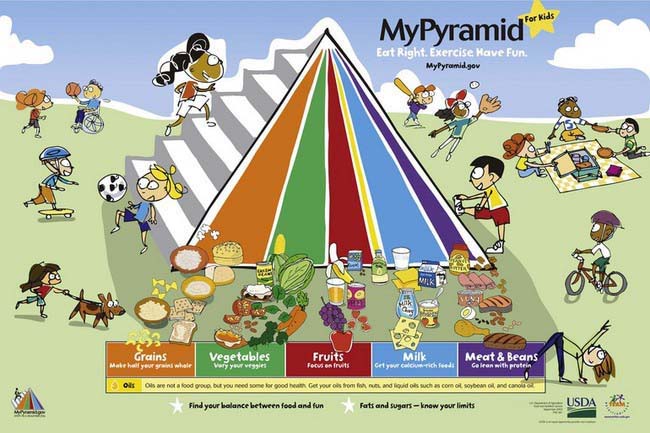

Most U.S. professional organizations and governmental agencies recommend the use of the USDA MyPyramid (www.mypyramid.gov) as a basis for building an optimal diet for children and adolescents. MyPyramid is based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. A personalized eating plan based on these guidelines provide, on average over a few days, all the essential nutrients necessary for health and growth, while limiting nutrients associated with chronic disease development. MyPyramid is aimed at the general public and differs from previous versions of the food pyramid in many ways. The intent is to primarily use MyPyramid as an Internet interactive tool that allows customization of recommendations, based on age, sex, physical activity, and, for some populations, weight and height. Print material is also available for families without Internet access.

Recommendations based on MyPyramid are given within 5 food groups (grains, vegetables, fruits, milk, and meat and beans) plus oils, with the general recommendations to eat, over time, a variety of foods within each food group. The graphic representation (Fig. 42-2) of slices symbolizes the average number of servings that should be consumed daily from each food group. In addition to these food groups, MyPyramid offers recommendations for physical activity to achieve a healthful energy balance. MyPyramid also provides information on discretionary calories, which are the foods that are not included in MyPyramid guidelines because of their low nutritional value, such as sweetened beverages, sweetened bakery products, or higher-fat meats. It should be noted that a diet based on MyPyramid, in order to provide all the necessary nutrients, allows a very small amount of discretionary calories available each day.

Eating at Home

At home, much of what children and adolescents eat is under the control of their parents. Typically, parents shop for groceries and they control, to some extent, what food is available in the house. It has been demonstrated that modeling of healthful eating behavior by parents is a critical determinant of the food choices of children and adolescents (Table 42-8). Therefore, pediatric counseling to improve diet should include guiding parents in using their influence to make healthier food choices available and attractive at home.

Table 42-8 FEEDING GUIDELINES FOR PARENTS

Adapted from Kleinman RE and the AAP Committee on Nutrition: Pediatric nutrition handbook, ed 6, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2009, American Academy of Pediatrics.

Nutrition Issues of Importance across Pediatric Ages

Food Environment

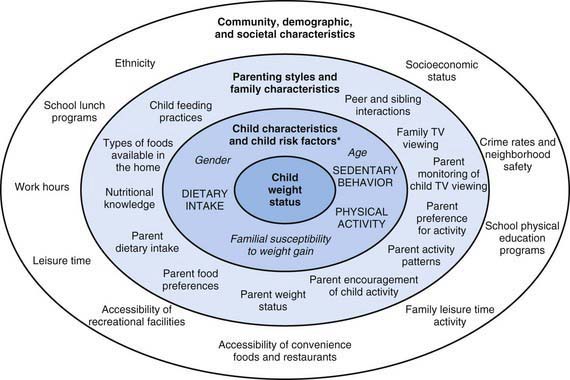

Most families have some knowledge of how to optimize nutrition and intend to provide their children with a healthful diet. The discrepancy between this fact and the actual quality of the diet consumed by U.S. children is often explained by difficulties and barriers for families to make healthful food choices. Because the final food choice is made by individual children or their parents, interventions to improve diet have focused on individual knowledge and behavior changes, but these have had limited success. One of the main determinants of food choice is taste, but other factors also influence these choices. One of the most useful conceptual frameworks to understand the child’s food environment in the context of obesity illustrates the variety and levels of the determinants of individual food and physical activity choices. Many of these determinants are not under the direct control of individual children or parents (Fig. 42-3). Understanding the context of food and lifestyle choices helps in understanding lack of changes or “poor compliance” and can decrease the frustration often experienced by the pediatricians who might “blame the victim” for behavior that is not entirely under their control.

Vegetarianism

Specific nutrients of concern in vegetarian diets include:

Nutrition as Part of Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Functional Foods, Dietary Supplements, Vitamin Supplements, and Botanical and Herbal Products

Pediatricians are often asked by parents if their children need to receive a daily multivitamin. Unless the child follows a particular diet that may be poor in one or more nutrients for health, cultural, or religious reasons, or if the child has a chronic health condition that puts him or her at risk for deficiency in one or more nutrients, multivitamins are not indicated. A diet that follows the guidelines of MyPyramid contains sufficient nutrients to support healthy growth. Of course, many children do not follow all the guidelines of MyPyramid, and parents and pediatricians may be tempted to use multivitamin supplements just to make sure that nutrient deficiencies are avoided. The problem with this approach is that multivitamin supplements do not provide all the nutrients that are necessary for good health, such as fiber or some of the antioxidants contained in food. Use of a daily multivitamin supplement can result in a false impression that the child’s diet is complete and in decreased efforts to meet dietary recommendations with food rather than the intake of supplements. As discussed in Chapter 41, the average U.S. diet provides more than a sufficient amount of most nutrients, including most vitamins. Therefore, multivitamins should not be routinely recommended.

Food Safety

Constantly keeping food safety issues in mind is an important aspect of feeding infants, children, and adolescents. In addition to choking hazards and food allergies, pediatricians and parents should be aware of food safety issues related to infectious agents and environmental contaminants. Food poisoning with infectious agents, either live bacteria or viruses or chemicals produced by these infectious agents, are most common with food consumed raw or undercooked, such as oysters, beef, eggs, and tomatoes, or cooked foods that have not been handled or stored properly. The specific infectious agents involved in food poisoning are described in Chapter 332. A good source of information for patients and parents can be found at www.foodsafety.gov.

Basnet S, Schneider M, Gazit A, et al. Fresh goat’s milk for infants: myths and realities—a review. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e973-e977.

Bhatia J, Greer F, Committee on Nutrition. Use of soy protein–based formulas in infant feeding. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1062-1068.

Cao Y, Calafat AM, Doerge DR, et al. Isoflavones in urine, saliva and blood of infants—data from a pilot study on the estrogenic activity of soy formula. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2009;19:223-234.

Cattaneo A. Promoting breast feeding in the community. BMJ. 2009;338:a2657.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state—national immunization survey, United States, 2004–2008. MMWR. 2010;59:327-334.

Faith MS, Scanlon KS, Birch LL, et al. Parent-child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obes Res. 2004;12:1711-1722.

Gale CR, Marriott LD, Martyn CN, et al. Breastfeeding, the use of docosahexaenoic acid-fortified formulas in infancy and neuropsychological function in childhood. Arch Dis Child. 2010;98:174-179.

Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL, et al. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: a guide for practitioners: consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005;112:2061-2075.

Grummer-Strawn LM, Reinold C, Krebs NF. Use of World Health Organization and CDC growth charts for children aged 0-59 months in the United States. MMWR. 2010;59(rr09):1-15.

Grummer-Strawn LM, Scanlon KS, Fein SB. Infant feeding and feeding transitions during the first year of life. Pediatrics. 2008;122:S36-S42.

Hoddinott P, Tappin D, Wright C. Breast feeding. BMJ. 2008;336:881-887.

Isaacs EB, Fischl BR, Quinn BT, et al. Impact of breast milk on intelligence quotient, brain size, and white matter development. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:357-362.

Jenik AG, Vain NE, Gorestein AN, et al. Does the recommendation to use a pacifier influence the prevalence of breastfeeding? J Pediatr. 2009;155:350-354.

Kleinman RL, editor. Pediatric nutrition handbook, ed 6, Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009.

Kumanyika SK. Environmental influences on childhood obesity: ethnic and cultural influences in context. Physiol Behav. 2008;94:61-70.

Lanigan J. Breastfeeding, early growth, and later obesity. Obes Rev. 2007;8:51-54.

Lawrence RM, Pane CA. Human breast milk: current concepts of immunology and infectious diseases. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2007;37:1-44.

Mann J. Vegetarian diets. BMJ. 2009;339:b2507.

Mozaffarian D, Rim EB. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health—evaluating the risks and the benefits. JAMA. 2006;296:1885-1899.

Myers GJ, Davidson PW. Maternal fish consumption benefits children’s development. Lancet. 2007;369:537-538.

Stallings VA, Yaktine AL, Institute of Medicine (U.S.), Committee on Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools. Nutrition standards for foods in schools: leading the way toward healthier youth. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007.

Udall JNJr. Infant feeding: initiation, problems, approaches. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2007;37:369-408.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture, Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2005, ed 6. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2005.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care interventions to promote breastfeeding: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:560-564.

Victora CG. Nutrition in early life: a global priority. Lancet. 2009;374:1123-1125.

Wagner CL, Greer FR, the Section on Breastfeeding and Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1142-1152.

World Health Organization. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding (website). www.who.int/childgrowth. Accessed May 14, 2010