CHAPTER 23 Feeding and Eating Conditions

Because eating is integral to survival, successful feeding of one’s child forms the bedrock of a healthy and fulfilling parent-child relationship. Perturbations in eating and feeding frequently come to the attention of a developmental-behavioral pediatrician. These conditions require a conceptualization of child development from medical, social, and psychological perspectives. The biological brain-based relationships between feeding and stress, emotion, and affect regulation are only just beginning to be explored. Feeding and eating disorders highlight social injustices, health disparities based on race and socioeconomic status, and the unique pressures on girls and women in our society. Finally, feeding and eating are fluid processes that rely on interaction with others and the environment and respond differentially to various influences over the course of the child’s development. They are, in summary, disorders particularly appropriate to the expertise of the developmental-behavioral pediatrician in the intersection of biology and behavior, parent-child relationships, the influence of societal issues on children’s well-being, and, most fundamentally, the myriad ways in which children change, physically, cognitively, and emotionally, as they grow.

23B. Infant Feeding Processes and Disorders

FEEDING DEVELOPMENT

The Dyadic Nature of Feeding

THE NURSING PERIOD

The full-term human infant is first nourished by a reciprocal process between the newborn and the mother. Breastfeeding is the prototype of the dyadic maternal-infant feeding relationship during the nursing period (first 4 to 6 months after birth). The neonate is born with primitive reflexes, including sucking and rooting that allow suckling during the first hours after birth. Gagging, a competing primitive reflex, may initially interfere with infant feeding. However, the infant’s suckling gradually increases in strength, frequency, and coordination over the first few days and, under normal circumstances, predominates over gagging. Colostrum, the first milk produced by the lactating breast, is produced in scant volume, which decreases the chance of choking, as well as regurgitation caused by overfilling of the stomach. The scant colostrum is gradually replaced with increasing volumes of transitional milk between the fourth and tenth postpartum day. By 14 days of age, the baby is usually an accomplished “nurser.”

Maternal lactation is regulated by a positive feedback loop. When suckling occurs, oxytocin and prolactin are released by the maternal hypothalamus, controlling milk ejection. Oxytocin release occurs as a conditioned response in most women and can be induced by seeing the baby or hearing the cry even before the tactile stimulus of suckling.1 Oxytocin and prolactin basal levels are elevated during the months of lactation and are higher 4 days post partum than during the third or fourth month of breastfeeding.2 Oxytocin levels in the perinatal period are influenced by characteristics of the infant, such as the infant’s birth weight. Levels are also influenced by exclusivity of breastfeeding over time, so that mothers who exclusively breastfeed have higher oxytocin and prolactin levels than do those who give supplementary feedings at 3 to 4 months. Prolactin and oxytocin have multiple influences on behaviors crucial to the survival of mammalian infants. Animal research demonstrates that oxytocin promotes maternal-infant bonding and prolactin inhibits sexual behaviors. Mammalian research contributes to the hypothesis that oxytocin and prolactin may contribute to maternal responsiveness during the attachment process. These neuroendocrine hormones may also contribute to decreased maternal interest in and responsiveness to outside stressors.

Both prolactin and oxytocin release are induced by suckling. Suckling-induced oxytocin release may be reduced by psychological stress, thereby reducing stimulation of milk flow (letdown).3 Infant suckling (on demand or frequently), provides the primary impetus that determines the actual volume of milk produced. It is difficult to overfeed a breastfed infant, because the baby influences the volume of milk by his or her own appetite and satiety. The infant hypothalamus processes infant hunger and satiety signals and coordinates stimulation and inhibition of infant feeding. This positive feedback loop can be perturbed by infant impairment such as muscle weakness or fatigue. For example, the infant with a weak suck may provide inadequate stimulation to the breast to induce oxytocin release and maintain an adequate milk supply. The positive feedback loop can also be disrupted by maternal mammary-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal dysregulation related to maternal fatigue, distress, or medication.

Social interaction takes place during feeding as well as during holding, rocking, stroking, and visual engagement. Social interaction develops with a burst in eye contact at 4 weeks of age.4 The infant may become increasingly social during suckling with interruptions to engage, laugh, or look around. These behaviors may be erroneously interpreted as lack of interest in feeding or desire to discontinue feeding, but they more accurately reflect the infant’s emerging capability of directing attention to other interests.

THE TRANSITIONAL FEEDING PERIOD

The transitional feeding period starts when the baby begins to ingest nonmilk food but continues to ingest a major portion of calories from milk. The timing and practices of the introduction of food to infants has varied historically and continues to vary widely across cultures. At about 1900, most infants in the United States were not fed solid food routinely until 12 months of age, but in the 1950s, mothers were encouraged to give 3-week old infants pureed or liquid food, such as pablum (rice cereal) and soft-cooked egg yolk. The American Academy of Pediatrics currently recommends gradual introduction of complementary foods containing iron at approximately 6 months of age.5 These recommendations are based on the infant’s neurodevelopmental ability to sit, hold the head erect, and turn the head when satiated, as well as scientific evidence that infants begin to need supplemental foods for calories and for iron in the second 6 months of life.

The dyadic nature of feeding does not diminish during the transitional feeding period. Infants lose some control over nutritional intake when supplemental foods are introduced, as they have less direct input into the timing, volume, and pace of feeding than during breastfeeding. However, if supplemental feeding begins beyond the neonatal and early infancy period (first 3 months), the infant’s capability to communicate desires and dislikes can aide in the self-regulation of feeding. Infants have variable capacity to signal hunger and satiety. Most newborns cry when they are hungry, but their early cries are not easily differentiated from cries for other needs such as for sleep and physical comfort.6 Therefore, these signals may be misinterpreted. As infants mature and develop relationships with caregivers, the human adult’s perceptual and problem-solving capability for interpreting the infant cry improves.6 It is quite likely that infants are sometimes fed when they are not hungry and that at times the amount may not match their desire.

ATTACHMENT THEORY

Feeding, beginning with the nursing period and continuing through the transitional feeding period and into the modified adult feeding period, is anchored in relationships. It is therefore important to consider attachment theory and how it relates to feeding development. Attachment is a behavioral system that conceivably operates in many infant behaviors, including normal feeding development. Furthermore, attachment theory can aid in the understanding of some feeding problems. In 1958, Bowlby hypothesized that human young must be equipped with a behavioral system that operates to promote sufficient proximity to the principal caregiver.7 He argued that attachment was important for humans because of their long period of immaturity and vulnerability. This system facilitated parental protection and therefore infant survival. His theory was based on the Darwinian notion of adaptation for survival of the species. Specific behaviors that attract the caregiver include crying, suckling, calling, smiling, and seeking proximity. Attachment theory describes attachment behaviors as a behavioral system, which differs from the use of the word attachment to mean a bond. Bowlby emphasized the importance of the infant’s confidence in the mother’s accessibility and responsiveness.8

Bowlby described four phases of attachment.9 The initial preattachment phase involves “orientation and signals without discrimination of figure.” This phase comes to an end within a few weeks after birth, when the infant can discriminate the mother figure from others. During the second phase, attachment in the making, the system involves “orientation and signals toward one or more discriminated figures.” The second phase lasts until the phase of clear attachment, which begins in the second half of the first year and involves the “maintenance of proximity to a discriminated figure by means of locomotion as well as signals.” This stage of attachment has been studied empirically.10 The final phase, goal-corrected partnership, which involves lessening of egocentricity and capability of seeing things from caretaker’s point of view, does not begin for most children until age 3 or 4 years.

Attachment is clearly entwined with feeding, inasmuch as feeding behaviors are an intricate part of the system of behaviors during preattachment and attachment in the making. Feeding both facilitates attachment and can be disturbed by disorders of attachment throughout early childhood.11 Feeding becomes a less important behavioral determinant of attachment during the phase of clear attachment as capabilities such as locomotion become operational.

The Context of Infant Feeding

CULTURE

Both within and outside of the United States, cultural norms strongly influence infant feeding practices. Breastfeeding initiation, frequency, and duration are influenced by cultural factors. Culture prescribes how the infant is held and for how long. Carrying and how the infant is carried (arms, sling, cradleboard, infant seat) is also culturally determined. Furthermore, where the infant sleeps, where the infant is placed when not held, and how the infant is clothed are all influenced by culture.12 In return, these practices influence feeding.

Cultural practices dictate when solid foods are introduced and whether bottle supplementation is started early. Health care providers may be integral in some cultures and may influence other cultures by their recommendations. Many families choose to feed their infants solid food earlier than the range of 4 to 6 months recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics.5 Mothers are often encouraged to introduce solid food (before the time recommended by physicians) by grandmothers who believe that infants’ sleep will improve if they have food in their stomachs at bedtime. Conversely, some groups choose to delay feeding until later than 6 months because of cultural beliefs (often related to a theory that longer exclusive breastfeeding is more natural and perhaps healthier for the baby). Similarly, toddler feeding may be accomplished in a high chair or by allowing the toddler to take food while moving from family member to family member. Parents may introduce food into their infant’s mouth by hand or by various types of utensils. Many American Indian and African American mothers chew food for their infant and then introduce small amounts into the infant’s mouth. This practice is seen in other contemporary and historical cultures. (Research on this practice as a risk for infectious diseases focuses on children exposed to this practice who present with infectious disease, and it suffers from lack of a denominator as well as control groups.)12a

FAMILY

Infant feeding is fraught with meaning for parents, especially mothers: “Successful feeding is inherently satisfying and a powerful affirmation of competence.”13 Conversely, mothers often interpret poor infant feeding as a sign that their mothering is defective. Some mothers generalize this belief and begin to feel that they themselves are defective because their babies do not eat. Clinical experience suggests that fathers also feel competent if their children eat well for them. However, fathers are less inclined to self-blame if their children have eating problems. The grandparents are often the repository of knowledge regarding childrearing and cultural practices. Therefore, grandparents view themselves as experts. This can be problematic if the parents do not choose to follow the feeding practices recommended by the grandparents. Conflicts between pediatric recommendations and grandparental recommendations about feeding are common. Some of these differences reflect changes that have taken place in pediatric knowledge and recommendations over a generation. Feeding problems can often cause stress for grandparents, who may wonder if they could do a better job than the parents. Grandparents do not always understand the complexity of feeding problems, which may stem from neurodevelopmental differences and parent-child relationship difficulties, often in a vicious cycle. Although parents need support from the grandparents, they also need consistent advice from all sources, including their family and doctors. Because infant/toddler feeding problems are poorly understood, the family is often confused by conflicting information and advice.

Normal Feeding Development

Full-term human infants are born with the ability to suck and swallow, to protect their airway, to perceive taste, and to regulate their appetite and satiety. Swallowing occurs as early as the 11th week of fetal life.14 The coordination of sucking, swallowing, and breathing is related to neuromuscular coordination, which is a function of gestational maturity.15 Although there is individual variation, most infants can adequately coordinate sucking, swallowing, and breathing by 35 weeks’ gestational age. In preterm infants, nonnutritive sucking bursts are seen at 31 to 33 weeks’ gestational age.16 The duration of each sucking burst is about 4 seconds, and as the infants mature, the period of time between sucking bursts decreases. Nutritive sucking allows approximately one suck and swallow per second.

The infant’s developing ability to take food off of a spoon and handle thicker foods depends on neuromuscular maturation, including loss of the extrusion reflex. Infants gradually develop the ability to keep their lips closed, thereby avoiding the loss of food from their mouth. Infants who are spoon-fed before 4 to 6 months of age are likely to use a sucking pattern to ingest pureed foods. By 9 months of age, most infants can chew by using a vertical jaw movement and can transfer food from the center of the mouth to the side. At this age, diagonal rotary jaw movements are emerging. By 12 months, most children can use a controlled, sustained bite for textured food, such as a soft cookie. Well-coordinated diagonal rotary and circular rotary jaw movements are attained by 18 and 24 months, respectively. Babies with neurodevelopmental disorders, including cerebral palsy, cleft lip and palate, and hypotonia syndromes, may present with feeding disorders or FTT. Extremes of oromotor tone—spasticity and hypotonia—often cause delay in feeding milestones. Sensory problems are discussed in the following section.

FEEDING CONCERNS, DISTURBANCES, AND DISORDERS

Deviations from normal development are described in the DSM-PC16a as normal variations, problems, and disorders. Variations of normal feeding may be accompanied by parental concerns, which are commonly handled by primary care pediatricians. They are included in this chapter because developmental-behavioral pediatricians are instrumental in training pediatric residents, and provide consultation about feeding problems to pediatric generalists and specialists. More serious feeding problems, as long as they do not impair growth, are called disturbances or perturbations in this chapter. Feeding disorders are more persistent than these problems and involve vomiting and/or poor growth. After these broad categories are discussed, more specific feeding disorders are described developmentally by presenting complaint.

Feeding Variations and Concerns

Parental concern about infant feeding problems is very common. At least 25% of parents of infants (in normative samples) express concern about their child’s eating.17–19 A longitudinal study of a normative sample of infants and toddlers in Sweden found that more than half of the mothers reported feeding concerns when their children were 10 months old and at the end of the second year. However, very few of the children were experiencing highly problematic feeding at both ages. In these cases, both infant temperament and maternal sensitivity were believed to mediate the development and the maintenance of the problem.20

Dr. Spock comments, “I suspect this mother is quoting me—with a touch of irritation and sarcasm.… I agree that she is in no mood to create a happy mealtime when she’s worried sick about a child’s meager and lopsided diet. And it isn’t just that she’s anxious. She can’t help being angry. She’s bought and cooked and served good food and this tiny, opinionated whippersnapper turns it down day after day.… Her worry is not just over his… health… but what her husband, her mother, the doctor, and the neighbors will say about him as he grows thinner and thinner, and what they’ll think about her.… The only thing she did, in the beginning, to bring this about was to be a conscientious mother. The guilt she feels for getting so mad, openly or inside, complicates the picture… as time goes on.21

Initial evaluation of feeding disorders is expected to take place in the primary care practice. Some physicians ask for developmental-behavioral pediatric consultation during the initial evaluation. When a parent expresses concern about a child’s feeding behavior, the pediatrician’s first task is to determine whether the child is growing adequately and then determine whether the feeding behavior is developmentally normal, problematic, or frankly disordered. Many parents are concerned about developmentally normal behavior, such as decreased intake at 1 year of age or throwing food at 9 months of age. When feeding behavior is normal, pediatric counseling can help parents avoid feeding battles. The development of frank feeding disorders may also be averted with appropriate anticipatory guidance, including pediatric counseling about age-appropriate feeding behaviors and normal growth parameters. The pediatrician can also explore parental strategies for feeding and support strategies that are helpful to the child. An example would include allowing the 12-month-old to do some finger feeding and limiting the mealtimes to 15 minutes in length (unless he is eating eagerly at 15 minutes). The pediatrician should listen for maladaptive strategies, such as force-feeding or punishing for not finishing food, and advise against such practices.

Feeding Disturbance

A feeding perturbation (intermittent problem) or disturbance (problem lasting more than one month) is diagnosed when an infant exhibits abnormal feeding with normal growth.22 Although the infant maintains adequate growth, the abnormal behavior causes significant distress for the family. Furthermore, the feeding disturbance may put the child at risk for future eating problems. The following case from our practice is an example of a 10-month-old with a feeding disturbance:

Feeding Disorder

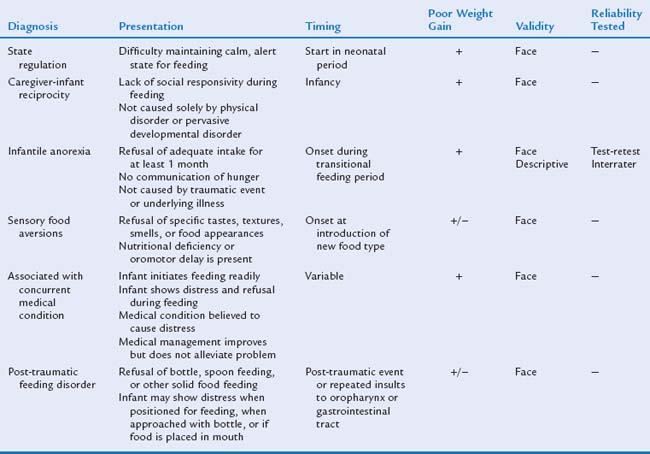

A feeding disorder (in comparison with a normal variation or problem) is a dysfunctional behavior that persists across time and situations and involves abnormal growth or vomiting. It may necessitate more intensive intervention. A system of classification of feeding disorders currently used for research was developed by Chatoor (Table 23B-1).23 These diagnostic categories were created on the basis of face validity (the extent to which the description of a category seems to accurately describe the characteristics of persons with a particular disorder).24 Infantile anorexia is the one diagnosis that has been studied for descriptive validity (the extent to which the features of a disorder are unique in comparison with other mental disorders), and reliability (how reliably a condition can be identified, as judged by test-retest and interrater reliability). Although this diagnostic schema has some limitations for both research and clinical practice, it is the only system of classification for infant feeding disorders that has been studied empirically. The remainder of this chapter describes the developmental and symptom manifestations of infant feeding disorders.

SPECIFIC INFANT FEEDING DISORDERS

Feeding Problem—Nursing Period

Feeding problems involving a breastfed infant can be related to the infant, to the mother, or to the maternal-infant dyad. It is reasonable to expect that breastfeeding problems that begin as isolated infant or maternal problems will quickly progress to involve the maternal-infant dyad. Examples of breastfeeding problems include inability to adequately coordinate sucking, swallowing, and breathing or inability to stimulate adequate breast milk production (Table 23B-2). Feeding disorders in formula-fed infants during the first 6 months of life can also result from the same issues except for stimulating breast milk production.

TABLE 23B-2 Feeding Problems during the Nursing Period That Are Related to Pathological Processes in the Infant

| Infant Feeding Problem | Example |

|---|---|

| Developmental disorder | Prematurity |

| Neurological disorder | Cerebral palsy |

| Anatomical disorder | Cleft palate |

| Transient feeding difficulty | Poor latching on |

| Disordered alertness, vigor | Sedation, mild asphyxia |

| Oral-motor delays | Mild neurological disorder |

Eating disorders that take root in the maternal-infant dyad are common. A feeding disorder of caregiver-infant reciprocity (previously called feeding disorder of attachment) can manifest during the nursing period.25 Both breastfed and formula-fed infants can develop feeding disorders when there is a disorder of caregiver-infant reciprocity. Criteria for this diagnosis include (1) onset between 2 and 8 months; (2) poor infant growth; (3) the presence of delays in cognitive, motor, or socioemotional development; (4) the presence of maternal psychopathological processes associated with lack of consistent care of the infant; and (5) poor parent-infant reciprocity during feeding. When feeding problems and poor growth are noted in the first 6 months of an infant’s life, poor attachment should be included in the differential diagnosis. Along with many other causes of failure of attachment, the clinician can consider the “ghosts in the nursery” described by Selma Fraiberg, in which unconscious response to previous losses and painful experiences in the mother’s life can distort interactions with the infant.26 For example, a mother who experienced a significant loss, such as the death of a parent or spouse, may have difficulty forming attachment to her infant. Subconscious fear of the pain associated with loss prevents closeness with the baby. Her lack of attachment translates into behavior. For example, she may tune out the baby’s crying or feed infrequently. Parents who have fewer unresolved losses are more available for knowing and responding to their child and interpreting the child’s behavior.

Feeding Refusal (Birth to Age 6 Months)

Feeding refusal may be seen during the first 6 months of life. Most infants who refuse to eat during the nursing period have had medical problems such as prematurity, intubation, surgery, or conditions that cause anorexia. Many of these infants are nutritionally supported with gastrostomy or nasogastric feeding. Currently, feeding therapy is provided inconsistently to these infants, and there is little research addressing the utility of feeding therapy in the development of normal eating in infants who have required tube feeding. In our experience, most of these infants eventually eat if they have the neurological capability to do so. However, some feeding refusal persists well into school age.27 A multidisciplinary approach to infant feeding refusal appears to be quite effective, albeit not empirically studied. An individualized combination of medical care, parental support, behavior modification, feeding practice, and desensitization for aversion is the current standard of care.

Feeding Refusal (Ages 6 to 18 Months)

Feeding problems during the transitional feeding period may be associated with an infant’s problem, a caretaker’s problem, or a disorder in the infant-caretaker dyad. Like feeding problems in the first 6 months of life, transitional feeding refusal associated with an infant’s problem is often related to a developmental, neurological, or anatomical disorder. During this developmental phase, some infants develop transient feeding refusal related to illness or distress. Most feeding refusal associated with temporary problems resolves and does not progress to the stage of a disorder. Even when an infant experiences anorexia, most infants respond to thirst and drink enough to remain hydrated. Table 23B-3 lists some causes in infant for feeding refusal in the transitional feeding period.

TABLE 23B-3 Possible Causes for Infants’ Feeding Refusal from 6 to 18 Months

Infants and toddlers may exhibit feeding refusal after trauma associated with the face or mouth or temporally with feeding. Posttraumatic feeding disorder has been well described in latency-age children after they experience choking, become preoccupied with a fear of eating, and refuse to eat.28 The following criteria can be used to diagnose posttraumatic feeding disorders in infants: (1) The infant demonstrates food refusal after a traumatic event or repeated traumatic events to the oropharynx or esophagus (e.g., choking, severe gagging, vomiting, reflux, acute allergic reaction, insertion of nasogastric or endotracheal tubes, suctioning, force-feeding); (2) the event (or events) triggered intense distress in the infant; (3) the infant experiences distress when anticipating feedings (e.g., when positioned for feeding, when shown the bottle or feeding utensils, and/or when approached with food); and (4) the infant resists feedings and becomes increasingly distressed when force-fed. Conditioned dysphagia has also been described in children with congenital heart disease, tracheoesophageal fistula, and gastroesophageal reflux.29–31 Research is needed to determine whether the pathophysiology of feeding problems associated with early oropharyngeal medical procedures or infantile illness is similar to that of posttraumatic feeding disorder in older children who have experienced choking.

Transition-stage feeding problems can relate to deficiencies in caretaker ability to assess the child’s hunger, satiety, and feeding needs. Some caretakers are not good at reading the infant’s hunger and satiety cues. The risk for cue insensitivity increases when the caretaker is inexperienced, exhausted, depressed, or hostile toward the infant. Some caretakers do not spontaneously interpret subtle signs, such as turning away, as infant communication. Furthermore, a developmentally inappropriate diet or feeding style can cause feeding refusal. Although some parents expect young infants to self-feed before they are capable, others continue to spoon-feed their infants long after the infant is capable of and desires self-feeding. Infants do not express hunger and satiety equally well. Refusal can result from a mismatch in the child’s developmental ability and feeding opportunities provided by the caretaker. Infants eat optimally in a pleasant, social feeding environment. A distracting or unsupportive feeding environment may be problematic. At the other extreme, force-feeding is aversive conditioning, and feeding refusal can result. Feeding problems initiated by a caretaker’s insensitivity or lack of knowledge can be best detected by a feeding observation. Standardized assessment tools are available for research.32,33 Development of simple assessment tools for practice are needed.

It is important to assess for individual infant-related and individual caretaker-related causes of feeding refusal; however, between 6 and 18 months of an infant’s age, disorders are likely to occur in the caretaker-infant relationship. Feeding refusal during transition to solid feeding is not typically related to poor attachment. Early individuation or beginning to separate from the symbiotic phase of infancy is a developmental challenge during the second half of the first year.34 Feeding problems may develop when caretakers are insensitive to the infant’s new developmental needs. Chatoor25,35 classifies feeding refusal during this developmental period as infantile anorexia with the following criteria: (1) refusal to eat adequate amounts of food for at least 1 month; (2) onset of the food refusal before 3 years of age, most commonly during the transition to spoon- and self-feeding, between 9 and 18 months of age; (3) lack of communication of hunger signals and lack of interest in food but interest in exploration and/or interaction with caregiver; (4) significant growth deficiency; (5) no preceding traumatic event; and (6) no underlying medical illness. Infantile anorexia is understood to stem from the infant’s increasing need for autonomy, often beginning with a battle of wills over the infant’s food intake. As the name infantile anorexia suggests, children with infantile anorexia characteristically lack appetite, beginning during infancy, seeming not to notice their own hunger. Although most infants with infantile anorexia have secure attachment to their mothers, they are somewhat more likely to have insecure mother-infant attachment than are picky eaters or normal controls. Furthermore, the likelihood of insecure attachment increases with worsening malnutrition.36

1 McNeilly AS, Robinson ICA, Houston MJ, et al. Release of oxytocin and prolactin in response to suckling. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:257-259.

2 Uvnas-Moberg K, Widstrom AM, Werner S, et al. Oxytocin and prolactin levels in breastfeeding women. Correlation with milk yield and duration of breastfeeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1990;69:301-306.

3 Ueda T, Yokoyama Y, Irahara M, et al. Influence of psychological stress on suckling-induced pulsatile oxytocin release. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:259-262.

4 Wolff P. The Development of Behavioral States and the Expression of Emotions in Early Infancy: New Proposals for Investigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

5 Gartner L, Morton J, Lawrence R, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496-506.

6 Barr RG, Hopkins B, Green JA, editors. Crying as a Sign, a Symptom, and a Signal. London: Mac Keith Press, 2000.

7 Bowlby J. The nature of a child’s tie to his mother. Int J Psychoanal. 1958;39:350-373.

8 Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss, Volume 2: Separation. New York: Basic Books, 1973.

9 Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss, Volume 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books, 1969.

10 Bretherton I, Waters E. Growing points in attachment theory and research. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 50(1–2, Serial No. 209), 1985.

11 Ward MJ, Kessler DB, Altman SC. Infant-mother attachment in children with failure to thrive. Infant Ment Health J. 1993;14:208-220.

12 Lawrence RA. Breastfeeding: A Guide for the Medical Profession. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1989.

12a. Steinkuller JS, Chan K, Rinehouse SE. Prechewing of food by adults and streptococcal pharyngitis in infants. J Pediatr. 1992;120:563-564.

13 Kedesdy JH, Budd KS, editors. Childhood Feeding Disorders: Biobehavioral Assessment and Intervention. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes, 1998.

14 Diamant NE. Development of esophageal function. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;131:S29-S32.

15 Bu’Lock F, Woolridge MW, Baum JD. Development of coordination of sucking, swallowing and breathing: Ultrasound study of term and preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1990;32:669-678.

16 Hack M, Estabrook MM, Robertson SS. Development of sucking rhythm in preterm infants. Early Hum Dev. 1985;11:133-140.

16a. American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Primary Care Version. Washington, DC: American Academy of Pediatrics, 1995.

17 Linscheid TR. Behavioral treatments for pediatric feeding disorders. Behav Modif. 2006;30:6-23.

18 McDonough S: Personal communication, 2007.

19 Gahagan S: Parental concern about eating behavior in early childhood. Submitted manuscript, 2007.

20 Hagekull B, Bohlin G, Rydell AM. Maternal sensitivity, infant temperament, and the development of early feeding problems. Infant Ment Health J. 1997;18:92-106.

21 Spock B. Dr. Spock Talks With Mothers-Growth and Guidance. Cambridge, MA: Riverside, 1961.

22 Anders TF. Clinical syndromes, relationship disturbances, and their assessment. In: Sameroff AJ, Emde RN, editors. Relationship Disturbances i n Ea rly Child hood. New York: Basic Books; 1989:125-144.

23 Chatoor I. Feeding disorders in infants and toddlers: diagnosis and treatment. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2002;11:163-183.

24 Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Classification of mental disorders and DSM-III. Kaplan H, Freedman AM, Sadock BJ, editors. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1980;4:1035-1072.

25 Chatoor I. Feeding disorders in infants and toddlers: Diagnosis and treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;11:163-183.

26 Fraiberg S, editor. Clinical Studies in Infant Mental Health: The First Year of Life. New York: Basic Books, 1980.

27 Lumeng JC, Perez M, Gahagan S. Does Treatment of Undernutrition w ith Gastrostomy T ube Feeding Worsen Childhood Eating Disorders? PAS. May 1, 2001. Pediatric Research, 2001.

28 Chatoor I, Conley C, Dickson L. Food refusal after an incident of choking: A posttraumatic eating disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:105-110.

29 Dellert SF, Hyams JS, Treem WR, et al. Feeding resistance and gastroesophageal reflux in infancy. J Pedatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;17:66-71.

30 Di Scipio WS, Kaslon K. Conditioned dysphagia in cleft palate children after pharyngeal flap surgery. Psychosom Med. 1982;44:247-257.

31 Skuse D. Identification and management of problem eaters. Arch Dis Child. 1993;69:604-608.

32 Barnard K: Caregiver/Parent-Child Interaction Feeding Manual. Seattle: University of Washington School of Nursing, NCAST Publications, 1994.

33 Chatoor I, Getson P, Menville E, et al. A feeding scale for research and clinical practice to assess mother-infant interactions in the first three years of life. Infant Ment Health J. 1997;18:76-91.

34 Egan J, Chatoor I, Rosen G. Nonorganic failure to thrive: Pathogenesis and classification. Clin Pro Child Hosp Nati Med Cent. 1980;36:173-182.

35 Chatoor I, Ganiban J, Surles J, et al. Physiological regulation and infantile anorexia: A pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1019-1025.

36 Chatoor I, Ganiban J, Hirsch R, et al. Maternal characteristics and toddler temperament in infantile anorexia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:743-751.

23C. Food Insecurity and Failure to Thrive

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Food insecurity and nutritional growth failure, frequently termed failure to thrive, are common pediatric problems in the United States and even larger issues globally.1,2 Although famine and malnutrition in the developing world are widely recognized, food insecurity in the United States remains relatively invisible. Food-insecure American children rarely resemble haunting images of hunger in the international media. However, many are not receiving adequate sustenance to support crucial development in early childhood. Insufficient nutrition, even without anthropometric changes, affects a child’s behavior, learning, and social interactions.3

A startling number of American children are at risk for FTT. A U.S. Department of Agriculture study4 revealed that in 2004, nearly 12% of U.S. households were “food insecure” (defined as being unable to obtain reliably sufficient nutritious food for an active, healthy life because of economic constraints). Food insecurity is even more prevalent among households with young children. Nearly 19% of American households with children younger than 6 years (the peak age for FTT) lacked consistent access to enough food for a healthy life in 2004.

Although not all children with FTT come from food-insecure families, poverty remains the most significant social risk factor for developing FTT. In some samples, as many as 10% of young, low-income American children meet criteria for FTT (see later “Diagnosis” section).5 Developmental-behavioral clinicians usually do not become involved in a child’s care until multiple cumulative experiences of food insecurity and associated medical and developmental risks manifest as FTT. As advocates for children, however, developmental-behavioral pediatricians should be aware that in low-income communities, children with FTT represent only part of a large problem. Many additional children experience food insecurity, which often acts as a precursor as well as a concomitant of FTT within a family, community, or population. FTT, in this regard, serves as a broad sentinel indicator of the health and well-being of children’s communities.6 The threshold at which persistent developmental-behavioral risk emerges in young children on the continuum from household food insecurity without growth failure to FTT has not been established. Research findings from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study7 suggest that living in a food-insecure household during kindergarten is correlated with impaired social skills in girls and depressed third grade reading and math scores in both boys and girls, even after confound control.

Undernutrition in a young child, often in concert with other factors, is the key but not sole mechanism that disrupts cognitive and socioemotional development in children with FTT.8 Studies of moderate to severe early malnutrition have shown detrimental effects on later cognitive measures,9 increased rates of behavioral and mental health disorders,10–13 and poorer school performance.14–16 As noted, it is not only severely affected children with anthropometric deficits who are at risk. Children’s physiology automatically conserves limited energy by decreasing social interaction and exploratory behavior.17 This results in lost opportunities for language, cognitive, and social development. A meta-analysis revealed that even more mildly affected children with FTT managed in the outpatient setting had demonstrable decrements on later cognitive measures.18 By virtue of their training, developmental-behavioral pediatricians are uniquely prepared to address the complex biopsychosocial factors, including proximal undernutrition, that contribute to FTT, with the goal of not only restoring growth but also ameliorating lasting developmental-behavioral sequelae.

ETIOLOGY

Too often, families of children with FTT are confronted with clinicians harboring the unstated assumption that the root cause of the child’s difficulties is related to poor “mothering.” This inaccurate perception springs from deep historical roots. The phrase failure to thrive was historically used by Spitz,19,20 in his classic studies in the 1940s of “hospitalism,” to describe children in orphanages suffering from “maternal deprivation.” The concept was extended by Coleman and Provence21 in the 1950s to describe two young children with feeding difficulties, growth retardation, and developmental delay living in college-educated families whose growth failure was, again, ascribed to “insufficient stimulation from the mother.” The primary therapeutic intervention recommended for these home-reared children was “to modify the parents’ attitude” or introduce a “mother substitute” via foster care.

Not until the groundbreaking work of Whitten and associates22 in 1969 was the primary role of malnutrition in the development of FTT recognized. Since then, the field has advanced rapidly; the simplistic “maternal deprivation” model has been replaced by a more sophisticated understanding of the interplay of medical, nutritional, social, and developmental risks. However, historical stereotypes often persist, and many children are referred to developmental-behavioral pediatricians for the assessment of presumed primary and causal maternal incompetence, psychiatric disturbance, or culpability without systematic investigation of medical, nutritional, developmental, and social context.

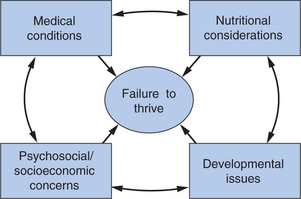

Moreover, developmental-behavioral pediatricians in their work with feeding disorders programs, neonatal follow-up clinics, and care of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities, autism, or other special health care needs may encounter children with complex cases of FTT. Thus, although diagnostically appealing, traditional dichotomous conceptualizations, such as organic versus nonorganic FTT, do not encompass the multifactorial causes of the disorder. Children with major medical conditions and FTT often have concomitant feeding or sensory issues. Families coping with a child’s serious illness often lack adequate social and economic supports to buffer the stress of the child’s condition. Conversely, apparently healthy children can have unidentified conditions like sleep-disordered breathing,23 gastroesophageal reflux,24 or subtle neurological dysfunction that contribute to their poor eating and growth. To be effective, the developmental-behavioral pediatrician must assess the child in the context of the entire family and, at a minimum, identify medical, nutritional, social, and developmental issues systematically and recommend further evaluation. In many settings, the developmental-behavioral pediatric practitioner must actually direct intensive diagnosis and treatment in these domains because effective management of affected children often exceeds the time available to primary care physicians. Rather than “ruling out” medical and nutritional conditions and then proceeding to address developmental and social issues, the successful practitioner, either alone or, ideally, with a multidisciplinary team, assesses and addresses these domains simultaneously, aware of how each affects the other. Current frameworks emphasize FTT as a “syndrome,” a diagnosis of which is, for each child, identified through a complex network of contributions (Fig. 23C-1).

FTT, once established, often becomes self-perpetuating without clinical intervention. The behavioral effects of malnutrition contribute to the maintenance of FTT. Malnourished children, less likely to seek interaction and make demands to be fed, often do not elicit adequate nutrients or interpersonal stimulation from their caregivers. In addition, malnutrition depresses secretory immunoglobulin A levels, impairs cell-mediated immunity, and disrupts cytokine regulation.25 Such compromised immune function manifests clinically as the frustrating malnutrition/infection cycle. As a result of functional immune compromise, children with FTT are more susceptible to illnesses such as gastroenteritis or otitis media. Caloric intake decreases, and utilization increases with each intercurrent illness, further inhibiting weight gain. From an ecological perspective, families struggle ineffectively to care for their ill and underweight child without adequate economic, physical, or social resources. The dynamic of a family dealing with a child’s FTT parallels that of other chronic conditions during the time the child’s growth is impaired. A complementary, multidisciplined approach—medical, nutritional, psychosocial, and developmental-behavioral—can validate caregivers’ concerns and result in more thorough assessment and effective management.

DIAGNOSIS

Accurate diagnosis begins with careful anthropometric measurement, plotting of growth parameters, and consideration of growth trajectories over time. FTT is most commonly defined as a child’s weight for age presenting at below the fifth percentile, a sustained decline in growth velocity, or a drop of more than two “major” percentiles after 18 months of age (e.g., a drop from the 50th to the 10th percentile). The child’s height (or length under age 2 years) for age, weight for height (or body mass index in older children), and head circumference, in addition to weight for age, help determine the direction (or necessity) of diagnostic evaluation, as well as intervention.

Clinicians should use the most recent growth charts for sex and age published by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), available online.26 By international consensus, the NCHS growth charts serve currently as the references for evaluating growth in young children regardless of ethnic or racial background.6 Despite their accepted use, these references include an unknown number of ill and deprived children and thus may be imprecise tools for identifying aberrant growth.6 The World Health Organization27 has developed standards for expected growth from a multiethnic, multinational sample restricted to healthy, initially breastfed children, which are publicly available.6 To avoid a factitious diagnosis of FTT, it also is important to correct the following anthropometric measurements for prematurity: correct weight for age until 24 months chronological age, height for age until 42 months, and head circumference for age until 18 months.28 Weight for length is not dependent on chronological or gestational age and does not require correction.

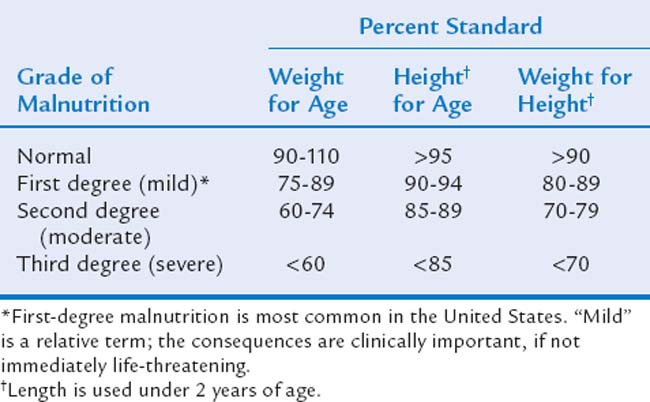

Frequently, scores on anthropometric measures of children with FTT fall below the lowest percentile shown on growth references, and growth failure must be classified more precisely than simply “less than the fifth percentile.” Therefore, a standardized system for further ranking the severity of growth deficit, developed by Gomez and associates29 and Waterlow,30 defines anthropometric measurements as “percent standards” (percentage of the median). For example, a child’s percent standard for weight for age is calculated by dividing his or her current weight by the median weight for chronological (or corrected) age and sex and multiplying by 100. This can be calculated for all four anthropometric measurements and allows identification of the degree of malnutrition. Table 23C-1 shows degrees of malnutrition based on percent standards for rapid clinical use. For research purposes, z-scores (standard deviation units) calculated from the NCHS growth grids are used, with parameters less than two standard deviations below the median (z-scores of −2 or lower) accepted as a threshold for identifying clinically serious malnutrition, even in developing countries.2

ASSESSMENT

Assessment of the child who “fails to thrive” touches on core family dynamics: what it means to be a good parent able to nourish and provide for a child. Thorough assessment, even when performed skillfully, can cause caregivers to feel that their most fundamental abilities are being questioned. Initial clinical encounters should cultivate a supportive relationship and include overt acknowledgment of caregivers’ desire to do the best for their child. Inviting families to partner with the clinical team lays a solid therapeutic foundation and empowers caregivers. At the same time, it is important to recognize the frustration many families feel when a child fails to thrive. Statements like “I can see you’ve tried several things to help Emily” and “We see many children with this problem” acknowledge the complementary perspectives of caregivers and clinicians, wherein one knows best the individual child and situation and the other has the benefit of broad experience and expertise. Because the origin of FTT is often multifactorial, a multidisciplinary assessment that includes medical, nutritional, psychosocial, and developmental parameters is important. Even in seemingly straightforward cases, thorough evaluation frequently identifies multiple causal contributors.

Medical History and Physical Examination

A history of low birth weight is associated with many developmental conditions and is a risk factor for later FTT.31 Both prematurity and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) can result in low birth weight but can have different implications for postnatal growth. Although, as discussed previously, growth parameters for children born prematurely must be corrected for gestational age, growth rates should be comparable with (or greater than) those of full-term infants.32 Formerly premature infants not growing at expected rates must be evaluated further. FTT in this population should not be attributed to “being born small.” A history of prematurity is only a starting point that allows associated behavioral, oromotor, neurological, and other medical issues to be identified and addressed. Regardless of gestational age, infants with IUGR are at risk for postnatal FTT.33 IUGR is conventionally defined as a birth weight less than the 10th percentile for gestational age. In this circumstance, it is important to determine the pattern of growth restriction. Symmetrical IUGR, with proportionate depression of weight, length, and head circumference at birth, carries a poorer prognosis for postnatal growth,34 often portending long-term abnormalities of growth and development.35 Asymmetrical growth restriction, which depresses weight to a greater degree than length or head circumference, has a better prognosis. This is because asymmetrical growth restriction is more likely to have had a maternal cause (such as preeclampsia) that is no longer present as an influence after birth. If provided optimal postnatal nutrition, infants with asymmetrical IUGR can often catch up in growth in the first years of life with subsequent normalization of growth trajectories.

Childhood conditions affecting growth are identified by a detailed history, review of systems, and physical examination. This should include information about chronic illnesses, consistency of medical care, hospitalizations or surgeries, medications, immunizations, allergies, and acquisition of developmental milestones. Family history should include both parents’ attained heights36 and both parents’ ages at pubertal onset, if known, as well as medical, psychiatric, and developmental diagnoses. A thorough review of systems may identify previously undiagnosed contributing conditions. Clinicians should ask about symptoms that the caregiver may not recognize as related to poor growth, including diarrhea, vomiting, cough, gagging, snoring, fevers, rash, and painful teeth. The status and current management of previously diagnosed chronic conditions such as asthma or cerebral palsy, including effects on the child’s daily appetite, energy demands, and dietary intake, as well as the effect on the quality of life of both child and caregivers, should be explored. Many medical conditions may contribute to the development of FTT. Although not an exhaustive summary, Table 23C-2 lists common medical contributors that can be identified by history, physical, and targeted laboratory assessment.

TABLE 23C-2 Common Medical Contributors to Failure to Thrive

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Laboratory Evaluation and Imaging

Historically it has been taught that laboratory evaluations identify very few occult causes of FTT. However, the data supporting this position date from the mid-1980s.37 Despite the more recent emergence of new diagnostic assessments for food allergies, celiac disease, and subtle genetic and nongenetic syndromes, the current validity of this assumption has not been reevaluated. Nevertheless, it remains true that laboratory assessment should be guided primarily by meticulous history and physical examination. Basic laboratory evaluation includes complete blood cell count with differential, lead measurement, free erythrocyte protoporphyrins measurement, urinalysis/urine culture, electrolyte measurements, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine measurements, and purified protein derivative skin test for tuberculosis; all of these are screens for common and treatable contributors to poor growth. Iron deficiency, with or without anemia, is seen at presentation in up to half of children with FTT, especially in low-income populations.38 Iron deficiency directly impairs growth, development, and behavior. It also increases anorexia and enhances environmental lead absorption, raising the risk of lead toxicity.39

Additional laboratory work should be obtained only as indicated by history and physical examination findings. This may include human immunodeficiency virus testing, a sweat test for cystic fibrosis, or serum immunoglobulin A and anti-transglutaminase antibodies to screen for celiac disease.40 Nutritional vitamin D deficiency can lead to rickets, especially in breastfed, dark-skinned infants in northern latitudes and should be sought in infants with suggestive physical findings or history.41 Zinc deficiency impairs growth, taste perception, and functional activity level and may also be part of targeted screening.42 Children with abdominal pain may benefit from testing for Helicobacter pylori infection.43 If the child is a recent immigrant or traveler, is living in a shelter, is attending a childcare program, or has been camping and has diarrhea or abdominal discomfort, evaluation for enteric pathogens such as Giardia lamblia and Cryptosporidium parvum would be appropriate. Radioallergosorbent or skin testing for food allergies should be considered in children with atopic dermatitis, chronic rhinitis, or wheezing. Children with dysmorphic features and cardiac or other malformations should undergo careful assessment for genetic and nongenetic syndromes that may contribute to growth failure (see Chapter 10B). Since the advent of neonatal screening, previously undiagnosed inborn errors of metabolism (see Chapter 10C) and primary endocrine causes of FTT, such as hypothyroidism, are usually identified perinatally but must be considered in selected cases especially among children born overseas or in states without comprehensive neonatal screening programs.

For children whose weight is decreased in proportion to height and for whom underlying causes remain unclear, a bone age can be helpful in differentiating constitutional short stature from stunting resulting from undernutrition. Children with constitutional short stature have a bone age commensurate with chronological age; in nutritionally or hormonally stunted children, bone age is less than chronological age and similar to height age. When diagnosing constitutional short stature, clinicians should be aware of a study indicating that children with the diagnosis of idiopathic short stature often have more problematic (picky) eating behavior and reduced body mass index, which thus warrants an attempt at nutritional intervention.44

Nutritional Considerations

Comprehensive, longitudinal nutritional assessment is crucial. Current intake and feeding practices, along with historical information, must be elicited. As noted in the section on feeding disorders, particular attention should be paid to vulnerable nutritional transition points, such as weaning from breast or bottle or the introduction of solids, which are often associated with the onset of growth difficulties. The timing of growth failure, correlated with nutritional transitions, may suggest possible causes. For example, a clinician identifying FTT in a newly formula-fed infant is advised to consider whether there is incorrect preparation of formula or insufficient family resources to purchase adequate formula. FTT occurring after the introduction of cow’s milk might suggest milk protein or lactose intolerance. Components of the nutritional assessment are summarized in Table 23C-3.

Several feeding issues are frequent contributors to FTT in children and merit specific mention. In infants, poor weight gain often results from breastfeeding difficulties, formula preparation errors, dilution of formula to stretch limited resources,45 and mixing large amounts of cereal into bottles. In toddlers and preschoolers, excessive consumption of juice,46 water, soda, tea, sports drinks, or thin soups instead of solids or milk is a common contributor. “Grazing” (eating frequently in very small amounts) suppresses appetite47 and often leads to poor weight gain in young children.

Family Resources and Psychosocial Concerns

Inadequate resources and psychosocial stressors frequently play a role in families of children with FTT. It is important to inquire directly about family composition, income sources, housing, childcare, social supports, and availability of food throughout the month. Neither full-time work nor the receipt of public support ensures adequate food in the home. The Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) nutrition program and food stamps provide only a portion of a family’s food expenses. These benefits are often tenuous, subject to time restrictions and maintenance of paperwork. Termination of benefits can tip the scales in an at-risk household. Families whose welfare benefits are terminated or reduced have an almost 50% higher risk of being food insecure than do similar families whose benefits are intact.48 Issues associated with poverty, including disconnected utilities and unreliable transportation, also negatively affect treatment success if not identified and addressed.

In all social strata, even the most privileged, the emotional functioning of family members is an important factor in children’s growth. A wide range of psychosocial factors contributes to the development of FTT (Table 23C-4). Caregiver psychopathology (particularly depression), substance use, and interpersonal violence distort caregiver-child interactions and can lead to unresponsive parenting, erratic feeding schedules, and, at times, frank neglect. Stress caused by the child’s condition may contribute additionally to caregiver depression. Sensitive interviewing helps identify these issues. Formal questionnaires also may be used to screen for caregiver depression.49 One community study revealed that mothers of young children with FTT were more likely to report increased symptons on depression screening.50 The quality of the home environment can be more difficult to ascertain without a home visit by a skilled clinician. Validated instruments such as the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment scale are often used, particularly in research.51

TABLE 23C-4 Common Psychosocial Contributors to Failure to Thrive

In assessing these concerns, the clinician must determine whether a child’s safety and well-being are at risk, and he or she must involve protective services when risk is indicated. In addition, although it is uncommon, school-aged children who present with the typical symptoms of hyperphagic short stature (formerly termed psychosocial dwarfism), including food scavenging, disrupted sleep, and encopresis or enuresis, often have a transient depression of growth hormone and are uniformly victims of serious and prolonged maltreatment. These children must be removed from the home or institution in which the maltreatment occurred.52

Developmental Issues

Children with FTT are at higher risk for developmental delay and may have reductions in exploratory behaviors, both resulting from and contributing to their malnutrition. Less interactive children receive diminished environmental stimulation and reinforcement. Transactionally, this can exacerbate underlying developmental vulnerabilities and delays, which results in more significant morbidity.53 The effects of early FTT on cognitive development are “dose” related: More severely affected children demonstrate a greater decrement on concurrent and later cognitive measures. In one analysis, pooled data from cases identified in primary care revealed FTT in infancy to have an effect size of −0.28 (−4.2 points) on later IQ testing.18 Of importance is that because FTT often occurs in children with other risk factors affecting cognitive development, the decrement related to the FTT may be only one of several factors negatively affecting the child’s development. Formal developmental assessment can identify delays and may lead to interventions that improve outcomes.

Children with underlying developmental conditions and specific difficulties contributing to FTT often benefit from additional evaluation. Examples include children with autism and food neophobia, oral aversion secondary to prolonged nasogastric feeding, poorly coordinated suck/swallow skills, and oromotor dysfunction.54 Occupational or speech therapy evaluation, with swallow study when indicated, can be helpful for the child presenting with oromotor dyscoordination or maladaptive oral motor tone (discussed earlier in this chapter). Such a referral helps rule out tactile hypersensitivity, swallowing difficulties, and other contributing factors. It also informs subsequent development of an appropriate feeding plan for caregivers specifying how food, as well as what kinds of foods, should be offered.

MANAGEMENT

Effective management of the child who fails to thrive is directed by information gathered during the clinical assessment. Identified contributing factors unique to each child and family must be comprehensively addressed, as discussed later in this chapter. Frequent follow-up with practical, responsive interventions as the condition evolves are crucial for successful management. The importance of active caregiver involvement and a multidisciplinary approach cannot be overstated. Research shows improved outcome with management by a multidisciplinary team, which includes, for example, a physician, a nutritionist, a social worker, a mental health provider, and, potentially, a speech and/or an occupational therapist.55

Medical Treatment

The most immediate issue in managing a child with FTT, even in the context of developmental-behavioral subspecialty care, is ensuring the child’s medical stability. Most children can be successfully managed as outpatients. Hospitalization is an added stress for families, disrupts mealtimes and feeding patterns, and increases risk for nosocomial infection. However, acute hospitalization is mandatory for a child classified as “severely malnourished” with third-degree malnutrition (see Table 23C-1) or for a child who fails to gain weight or continues to consistently lose weight despite aggressive outpatient management, as well as for children with serious, intercurrent infections or uncontrolled chronic illnesses.

Nutritional Intervention

The initial objective of nutritional intervention is for the child to consume enough calories to enable catch-up growth. Adequate catch-up growth rates for children with FTT can be as much as two to three times average rates (available in Table 23C-5).56 This is clearly a challenge because, by definition, these children are not maintaining even average rates of weight gain. Depending on severity of malnutrition at presentation, catch-up growth rates must be maintained for 4 to 9 months to restore a child’s weight for height.57

TABLE 23C-5 Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) and Growth Rates for Children

| Age | RDA (kcal/kg/day) | Median Weight Gain (grams/day) |

|---|---|---|

| 0-3 months | 108 | 26-31 |

| 3-6 months | 108 | 17-18 |

| 6-9 months | 98 | 12-13 |

| 9-12 months | 98 | 9 |

| 1-3 years | 102 | 7-9 |

| 4-6 years | 90 | 6 |

From National Resource Council, Food and Nutrition Board: Recommended Daily Allowances. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, 1989.

Nutritional intervention begins with ensuring that caregivers are engaged and understand therapeutic goals. Success may necessitate involving all current caregivers of the child (for example, including a grandmother or childcare worker) or putting together nutritional plans for the preschool. Caregiver education about what constitutes a healthy diet and children’s dietary needs at particular ages provides the basis for diet modification and additional intervention. Families receive nutritional misinformation from multiple sources including cultural traditions, well-meaning family and friends, television, and commercial advertising. Common misconceptions include the constipating effect of iron in infant formula, the nutritional value of fruit juice, perceived benefits of allowing an underweight child to graze and eat many sweets, and the appropriateness of adult low-fat diets for children.58 In addition to correcting misconceptions, clinicians should not assume that caregivers are familiar with basic nutritional tenets. Important concepts must be explicit reviewed. Caregivers may need to be taught to offer solids before liquids, that young children require both morning and afternoon snacks, to decrease juice intake to 4 to 6 oz/day, and to limit snacks and drinks with low caloric density and nutritional value. The importance of structured family meals without television and the developmental basis for feeding behaviors and food choices often merit review with families.

Although caregiver education is crucial, it is equally important to present a concrete plan addressing a child’s particular needs. Many caregivers respond positively to a formal feeding plan drawn up in collaboration with the clinician. A written schedule listing times for meals (three per day) and snacks (two to three per day), along with suggested meal choices based on a child’s preferences, is helpful, especially for less experienced parents or multiple caregiver situations. Dietary modification and nutritional intervention should be based on a child’s caloric needs. The caloric intake needed for catch-up growth can be estimated by dividing the average calorie requirement for age (as listed in Table 23C-5) by the child’s weight as a percentage of median weight for age. For example, a 12-month-old (average requirement for age, 102 kcal/kg) who weighs 75% of the median weight for age would need 102/0.75, or 136 kcal/kg/day.59 Depending on the severity of the initial malnutrition and the nutritional stresses of acute or chronic illness, a child may require as much as two times maintenance calories for adequate catch-up growth.

For some mildly affected children, target intake can be achieved by dietary manipulation: increasing caloric density without specialized supplementation. Many children, however, require a period of specialized oral supplementation, the options for which are presented in Table 23C-6 and depend on a child’s age and needs. If available, consultation with a registered dietitian is recommended. It is rare for a child to be unable to consume adequate supplementation orally, but in such cases, nasogastric or gastrostomy tube feedings improve weight gain and must be implemented.60 With these severely affected children, formal consultation with hospital-based nutrition support services is necessary. After a period of supplemental nutrition, a child should be monitored closely until the clinician ensures that the child can be weaned successfully to a regular diet administered orally and maintain normal rates of growth without supplementation.

TABLE 23C-6 Basic Nutritional Supplementation

| Type | Calories Provided | How to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Fortified infant formulas | Variable | Increase caloric concentration |

| Polycose powder | 23 kcal/tbsp | Add to formula or food |

| Instant breakfast mix | 130 kcal/packet | Add to whole milk |

| PediaSure, Nutren, Boost, Bright Beginnings | 30 kcal/oz | Ready to feed |

| Duocal | 42 kcal/tbsp | Add to formula, milk, food |

Finally, the clinician must remember that a diet inadequate in calories and protein is frequently deficient in micronutrients as well. Catch-up growth rates increase micronutrient demand and may additionally deplete a child’s micronutrient stores. For these reasons, all children with FTT should receive a daily multivitamin/multimineral preparation containing iron, calcium, and zinc. This ensures micronutrient intake, allowing caregivers to focus on increasing dietary calories rather than worrying about vitamin and micronutrient content. Children with frank anemia should receive therapeutic iron dosing until the anemia is corrected, and those with rickets should be treated with therapeutic doses of vitamin D.41

Addressing Developmental Needs

Caregiver observation of formal developmental testing can invite discussion of a child’s particular abilities and challenges. For children at risk for or found to have developmental delay, referral to early intervention programs (for children 36 months or younger) or to the public school system (for those older than 36 months) is imperative. Formal programs to enhance development result in improved outcomes for children with FTT,61,62 particularly language and cognitive development in children younger than age 2 years.63,64 Children with oromotor dysfunction secondary to neurological or developmental conditions often require specialized occupational therapy intervention with gradual introduction of foods and textures to develop age-appropriate competencies.65

Implications

Ironically, young children who are most vulnerable to the developmental effects of undernutrition are also most likely to experience it. Malnutrition uniquely affects the developing brain. In infants and young children, the growing brain accounts for up to 80% of the body’s glucose usage.66 This sensitive developmental period is characterized by biosynthetic capabilities and neural genesis that do not persist into later life.54,67 When a young child experiences undernutrition, these processes are compromised. Depending on the timing, duration, and severity of malnutrition, the effect is potentially lifelong. Current deprivation and future life course are linked irrevocably.

Much remains to be learned about the long-term effects of food insecurity and FTT in childhood. Research findings suggest that the implications for later health may be broader than previously appreciated. Animal and human studies have identified catch-up growth in early childhood (rapid weight gain after a period of undernutrition) as a risk factor for obesity and adult-onset type 2 diabetes later in life.68,69 In short, the same metabolic adaptations that work to minimize detrimental effects of undernutrition on brain growth during the perinatal period and early childhood period may paradoxically contribute to the development of obesity when nutrition is no longer compromised. Nevertheless, intact cognition and behavior are irreducible requirements for functioning successfully in the modern world, and they must be preserved.

1 El-Ghannam A. The global problems of child malnutrition and mortality in different world regions. J Health Soc Policy. 2003;16(4):1-26.

2 deOnis M, Blossner M, Borghi E, et al. Estimates of global prevalence of childhood underweight in 1990 and 2015. JAMA. 2004;291:2600-2606.

3 Weinreb L. Hunger: Its impact on children’s health and mental health. Pediatrics. 2002;110(4):e41.

4 Nord M, Andrews M, Carlson S: Household Food Security in the United States, 2003. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, 2004. (Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err11/; accessed 2/5/07.)

5 Frank D, Drotar D, Cook J, et al. Failure to thrive. In: Reece R, Ludwig S, editors. Child Abuse: Medical Diagnosis and Management. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:307-338.

6 Garza C, deOnis M. Rationale for developing a new international growth reference. Food Nutr Bull. 2004;25(1):S5-S14.

7 Jyoti D, Frongillo E, Jones S. Food insecurity affects children’s academic performance, weight gain, and social skills. J Nutr. 2005;135:2831-2839.

8 Galler JR, Barrett L. Children and famine: Long-term impact on development. Ambul Child Health. 2001;7(2):85-95.

9 Liu J, Raine A, Venables PH, et al. Malnutrition at age 3 years and lower cognitive ability at age 11 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:593-600.

10 Galler JR, Ramsey F. A follow-up study of the influence of early malnutrition on development: Behavior at home and at school. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:593-600.

11 St. Clair D, Xu M, Wang P, et al. Rates of adult schizophrenia following prenatal exposure to the Chinese famine of 1959–1961. JAMA. 2005;294:557-562.

12 Neugebauer R, Hoek H, Susser E. Prenatal exposure to wartime famine and development of antisocial personality disorder in early adulthood. JAMA. 1999;282:455-462.

13 Susser E, Neugebauer R, Hoek K, et al. Schizophrenia after prenatal famine: Further evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:25-31.

14 Galler JR, Famsey S, Solimano G. The influence of early malnutrition on subsequent behavioral development III: Learning disabilities as a sequel to malnutrition. Pediatr Res. 1984;18:309-313.

15 Kerr M, Black M, Krishnakumar A. Failure-to-thrive, maltreatment and the behavior and development of 6-year-old children from low-income, urban familes: A cumulative risk model. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24:587-598.

16 Dykman R, Casey P, Ackerman P, et al. Behavioral and cognitive status in school-aged children with a history of failure to thrive during early childhood. Clin Pediatr. 2001;40:63-70.

17 Beaton G. Nutritional needs during the first year of life: Some concepts and perspectives. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1985;32:275-288.

18 Corbett S, Drewett R. To what extent is failure to thrive in infancy associated with poorer cognitive development? A review and metanalysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:641-654.

19 Spitz R. Hospitalism. Psychoanal Study Child. 1945;1:53.

20 Spitz R. Hospitalism: A following-up report. Psychoanal Study Child. 1946;2:113.

21 Coleman R, Provence S. Environmental retardation (hospitalism) in infants living in families. Pediatrics. 1957;19:285-292.

22 Whitten C, Pettit M, Fischhoff J. Evidence that growth failure from maternal deprivation is secondary to undereating. JAMA. 1969;209:1675-1682.

23 Bonuck K. Sleep-disordered breathing and failure to thrive: Research vs practice. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:299-300.

24 Hassall E. Decisions in diagnosing and managing chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. J Pediatr. 2005;146:S3-S12.

25 Chevalier P, Sevilla R, Sejas R, et al. Immune recovery of malnourished children takes longer than nutritional recovery: Implication for treatment and discharge. J Trop Pediatr. 1998;44:304-307.

26 National Center for Health Statistics: 2000 CDC Growth Charts: United States. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2000. (Available at: www.cdc.gov/growthcharts; accessed 2/5/07.)

27 World Health Organization: The WHO Child Growth Standards. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, undated. (Available at: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/en/; accessed 2/5/07.)

28 Brandt I. Growth dynamics of low birthweight infants with emphasis on the perinatal period. In: Falkner F, Tanner J, editors. Human Growth, Neurobiology and Nutrition. New York: Plenum Press; 1979:415-475.

29 Gomez F, Galvan R, Frenk S, et al. Mortality in second and third degree malnutrition. J Trop Pediatr. 1956;2:77-83.

30 Waterlow J. Classification and definition of protein-calorie malnutrition. BMJ. 1972;3:566-569.

31 Dusick A, Poindexter B, Ehrenkranz R, et al. Growth failure in the preterm infant: Can we catch up? Semin Perinatol. 2003;27:302-310.

32 Casey P, Kraemer HC, Bernbaum J, et al. Growth status and growth rates of a varied sample of low birth weight, preterm infants: A longitudinal cohort from birth to three years of age. J Pediatr. 1991;119:599-605.

33 Hediger M, Overpeck MD, Maurer KR, et al. Growth of infants and young children born small or large for gestational age. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:1225-1231.

34 Luo Z, Albertsson-Wikland K, Karlberg J. Length and body mass index at birth and target height influences patterns of postnatal growth in children born small for gestational age. Pediatrics. 1998;102(6):E72.

35 Frisk V, Amsel R, Whyte H. The importance of head growth patterns in predicting the cognitive abilities and literacy skills of small-for-gestational-age children. Dev Neuropsychol. 2002;22:565-593.

36 Blair P, Drewett R, Emmett P, et al. Family, socioeconomic and prenatal factors associated with failure to thrive in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:839-847.

37 Berwick DM, Levy JC, Kleinerman R. Failure to thrive: Diagnostic yield of hospitalization. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57:347-351.

38 Bithoney W, Ratbun J. Failure to thrive. In: Levine M, Carey WB, Cracker AC, editors. Developmental-Behavioral. Pediatrics Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1983:557-572.

39 Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Hagen J, et al. Poorer behavioral and developmental outcome more than 10 years after treatment for iron deficiency in infancy. Pediatrics. 2001;105(4):e51.

40 Catassi C, Farsano A. Celiac disease as a cause of growth retardation in childhood. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16:445-449.

41 Gartner L, Greer F. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency: New guidelines for vitamin D intake. Pediatrics. 2003;111:908-910.

42 Black M. Zinc deficiency and child development. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:464S-469S.

43 Yang Y, Sheu B, Lee S, et al. Children of Helicobacter pylori-infected mothers are predisposed to H. pylori acquisition with subsequent iron deficiency and growth retardation. Helicobacter. 2005;10:249-255.

44 Wudy S, Hagemann S, Dempfle A, et al. Children with idiopathic short stature are poor eaters and have decreased body mass index. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):e52-e57.

45 Fein S, Falci C. Infant formula preparation, handling and related practices in the United States. J Am Diet Soc. 1999;99:1234-1240.

46 Dennison B. Fruit juice consumption by infants and children: A review. J Am Coll Nutr. 1996;15:4S-11S.

47 Haptinstall F, Puckering C, Skuse D, et al. Nutrition and mealtime behavior in families of growth retarded children. Hum Nutr Appl Nutr. 1987;41(A):390-402.

48 Cook J, Frank DA, Berkowitz C, et al. Welfare reform and the health of young children: A sentinel survey in 6 cities. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;156:678-684.

49 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Depression. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:760.