CHAPTER 17 Fecal Incontinence

Fecal incontinence is usually defined as the involuntary passage of fecal matter through the anus or the inability to control the discharge of bowel contents. The severity of incontinence can range from occasional unintentional elimination of flatus to the seepage of liquid fecal matter or the complete evacuation of bowel contents. Consequently, the problem has been difficult to characterize from an epidemiologic and pathophysiologic standpoint, but undoubtedly causes considerable embarrassment, a loss of self-esteem, social isolation, and a diminished quality of life.1

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Fecal incontinence affects people of all ages, but its prevalence is disproportionately higher in middle-aged women, older adults, and nursing home residents. Estimates of the prevalence of fecal incontinence vary greatly and depend on the clinical setting, definition of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, and influence of social stigma and other factors.2 Both the embarrassment and social stigma attached to fecal incontinence make it difficult for subjects to seek health care; consequently, treatment is often delayed for several years. Fecal incontinence not only causes significant morbidity in the community, but also consumes substantial health care resources.

In a U.S. householder survey, frequent leakage of stool or fecal staining for more than one month were reported by 7.1% and 0.7% of the population, respectively.3 In the United Kingdom, two or more episodes of fecal incontinence per month were reported by 0.8% of patients who presented to a primary care clinic.4 In an older self-caring population (older than 65 years), fecal incontinence occurred at least once a week in 3.7% of subjects and in more men than women (ratio of 1.5 : 1).5 The frequency of fecal incontinence increases with age, from 7% in women younger than 30 years to 22% in women in their seventh decade.6,7 By contrast, 25% to 35% of institutionalized patients and 10% to 25% of hospitalized geriatric patients have fecal incontinence.1 In the United States, fecal incontinence is the second leading reason for placement in a nursing home.

In a survey of 2570 households, comprising 6959 individuals, the frequency of at least one episode of fecal incontinence during the previous year was 2.2%; among affected persons, 63% were women, 30% were older than 65 years, 36% were incontinent of solid stool, 54% were incontinent of liquid stool, and 60% were incontinent of flatus.1 Furthermore, in another prospective survey of patients who attended either a gastroenterology or a primary care clinic, over 18% reported fecal incontinence at least once a week.8 Only one third had ever discussed the problem with a physician. When stratified for the frequency of episodes, 2.7% of patients reported incontinence daily, 4.5% weekly, and 7.1% monthly.8 In another survey, fecal incontinence was associated with urinary incontinence in 26% of women who attended a urology-gynecology clinic.9 A high frequency of mixed fecal and urinary incontinence was also reported in nursing home residents. Persons with incontinence were 6.8 times as likely to miss work or school, and missed an average of 50 work or school days per year, compared with those without incontinence or other functional gastrointestinal symptoms.3

HEALTH CARE BURDEN

The cost of health care related to fecal incontinence includes measurable components such as the evaluation, diagnostic testing, and treatment of incontinence, the use of disposable pads and other ancillary devices, skin care, and nursing care. Approximately $400 million/year is spent on adult diapers,8 and between $1.5 and $7 billion/year is spent on care for incontinence among institutionalized older patients.1,2,10 In a long-term facility, the annual cost for a patient with mixed fecal and urinary incontinence was $9,711.11 In the outpatient setting, the average cost per patient (including evaluation) has been estimated to be $17,166.12 In addition, these persons incur costs that cannot be easily measured and that result from their impaired quality of life and social dysfunction.7 Fecal incontinence is most likely to affect a person’s quality of life significantly and lead to increased use of health care, predominantly in women with moderate to severe symptoms.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE ANORECTUM

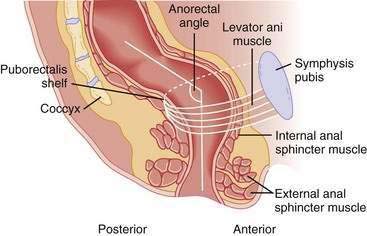

A structurally and functionally intact anorectal unit is essential for maintaining normal continence of bowel contents (see Chapters 98 and 125).13 The rectum is a hollow muscular tube composed of a continuous layer of longitudinal muscle that interlaces with the underlying circular muscle. This unique muscle arrangement enables the rectum to serve both as a reservoir for stool and as a pump for emptying stool. The anus is a muscular tube 2 to 4 cm in length that at rest forms an angle with the axis of the rectum (Fig. 17-1). At rest, the anorectal angle is approximately 90 degrees; with voluntary squeeze, the angle becomes more acute, approximately 70 degrees; and during defecation the angle becomes obtuse, about 110 to 130 degrees.

Figure 17-1. Sagittal diagrammatic view of the anorectum.

(From Rao SSC. Pathophysiology of adult fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology 2004; 126:S14-22.)

The anal sphincter consists of two muscular components—the internal anal sphincter (IAS), a 0.3- to 0.5-cm thick expansion of the circular smooth muscle layer of the rectum, and the external anal sphincter (EAS), a 0.6- to 1.0-cm thick expansion of the levator ani muscles. Morphologically, both sphincters are separate and heterogenous.14 The IAS is composed predominantly of slow-twitch, fatigue-resistant smooth muscle and generates mechanical activity with a frequency of 15 to 35 cycles/min as well as ultraslow waves at 1.5 to 3 cycles/min.13 The IAS contributes approximately 70% to 85% of the resting anal sphincter pressure but only 40% of the pressure after sudden distention of the rectum and 65% during constant rectal distention; the remainder of the pressure is provided by the EAS.15 Therefore, the IAS is responsible chiefly for maintaining anal continence at rest.

The anus is normally closed by the tonic activity of the IAS. This barrier is reinforced during voluntary squeeze by the EAS. The anal mucosal folds, together with the expansive anal vascular cushions (see later), provide a tight seal.16 These barriers are augmented by the puborectalis muscle, which forms a flap-like valve that creates a forward pull and reinforces the anorectal angle.13

The anorectum is richly innervated by sensory, motor, and autonomic nerves and by the enteric nervous system. The principal nerve to the anorectum is the pudendal nerve, which arises from the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves (S2, S3, S4), innervates the EAS, and subserves sensory and motor function.17 A pudendal nerve block creates a loss of sensation in the perianal and genital skin and weakness of the anal sphincter muscle but does not affect rectal sensation.15 A pudendal nerve block also abolishes the rectoanal contractile reflexes (see later), an observation that suggests that pudendal neuropathy may affect the rectoanal contractile reflex response. The sensation of rectal distention is most likely transmitted along the S2, S3, and S4 parasympathetic nerves. These nerve fibers travel along the pelvic splanchnic nerves and are independent of the pudendal nerve.13

How humans perceive stool contents in the anorectum is not completely understood. Earlier studies failed to demonstrate rectal sensory awareness.13 Subsequent studies have confirmed that balloon distention is perceived in the rectum and that such perception plays a role in maintaining continence.16,18 Furthermore, sensory conditioning can improve hyposensitivity19,20 and hypersensitivity21 of the rectum. Mechanical stimulation of the rectum can produce cerebral evoked responses,22 thereby confirming that the rectum is a sensory organ.

Although organized nerve endings are not present in the rectal mucosa or myenteric plexus, myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers are present.13 These nerves most likely mediate the distention or stretch-induced sensory responses as well as the viscerovisceral,22 rectoanal inhibitory, and rectoanal contractile reflexes. The sensation of rectal distention is most likely transmitted via the parasympathetic nervi erigentes along the S2, S3, and S4 splanchnic nerves. Rectal sensation and the ability to defecate can be abolished completely by resection of the nervi erigentes.23 If parasympathetic innervation is absent, rectal filling is perceived only as a vague sensation of discomfort. Even persons with paraplegia or sacral neuronal lesions may retain some degree of sensory function, but almost no sensation is felt if lesions occur in the higher spine.15,18,24 Therefore, the sacral nerves are intimately involved in the maintenance of continence.

The suggestion has been made that bowel contents are sensed periodically by anorectal sampling,25 the process whereby transient relaxation of the IAS allows the stool contents from the rectum to come into contact with specialized sensory organs in the upper anal canal. Specialized afferent nerves may exist that subserve sensations of touch, temperature, tension, and friction, but the mechanisms are incompletely understood.13 Incontinent patients appear to sample rectal contents less frequently than continent subjects. The likely role of anal sensation is to facilitate discrimination between flatus and feces and the fine-tuning of the continence barrier, but its precise role has not been well characterized. Rectal distention is associated with a fall in anal resting pressure known as the rectoanal inhibitory reflex. The amplitude and duration of this relaxation increases with the volume of rectal distention. This reflex is mediated by the myenteric plexus and is present in patients in whom the hypogastric nerves have been transected and in those with a spinal cord lesion. The reflex is absent after transection of the rectum, but it may recover.18 Although the rectoanal inhibitory reflex may facilitate discharge of flatus, rectal distention is also associated with a rectoanal contractile response, a subconscious reflex effort to prevent release of rectal contents, such as flatus.26,27 This contractile response involves contraction of the EAS and is mediated by the pelvic splanchnic and pudendal nerves. The amplitude and duration of the rectoanal contractile reflex also increases with rectal distention, up to a maximum volume of 30 mL. Abrupt increases in intra-abdominal pressure, as caused by coughing or laughing, are associated with an increase in anal sphincter pressure. A number of mechanisms, including reflex contraction of the puborectalis, may be involved.

The blood-filled vascular tissue of the anal mucosa also plays an important role in producing optimal closure of the anus. An in vitro study has shown that even during maximal involuntary contraction, the internal sphincter ring is unable to close the anal orifice completely, and a gap of approximately 7 mm remains. This gap is filled by the anal cushions, which may exert pressures of up to 9 mm Hg and thereby contribute 10% to 20% to the resting anal pressure.26

PATHOGENIC MECHANISMS

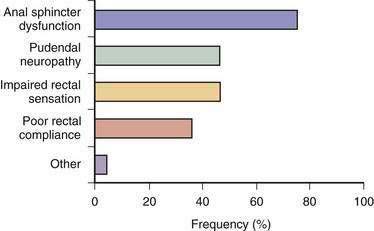

Fecal incontinence occurs when one or more mechanisms that maintain continence is disrupted to the extent that other mechanisms are unable to compensate. Therefore, fecal incontinence is often multifactorial.2,27 In a prospective study, 80% of patients with fecal incontinence had more than one pathogenic abnormality (Fig. 17-2).13 Although the pathophysiologic mechanisms often overlap, they can be categorized under four broad groups, as summarized in Table 17-1.

Table 17-1 Mechanisms, Causes, and Pathophysiology of Fecal Incontinence

| MECHANISM | CAUSES | PATHOPHYSIOLOGY |

|---|---|---|

| Abnormal Anorectal or Pelvic Floor Structures | ||

| Anal sphincter muscle | Hemorrhoidectomy, neuropathy, obstetric injury | Sphincter weakness, loss of sampling reflex |

| Puborectalis muscle | Aging, excessive perineal descent, trauma | Obtuse anorectal angle, sphincter weakness |

| Pudendal nerve | Excessive straining, obstetric or surgical injury, perineal descent | Sphincter weakness, sensory loss, impaired reflexes |

| Nervous system, spinal cord, autonomic nervous system | Avulsion injury, spine surgery, diabetes mellitus, head injury, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, stroke | Loss of sensation, impaired reflexes, secondary myopathy, loss of accommodation |

| Rectum | Aging, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, prolapse, radiation | Loss of accommodation, loss of sensation, hypersensitivity |

| Abnormal Anorectal or Pelvic Floor Function | ||

| Impaired anorectal sensation | Autonomic nervous system disorders, central nervous system disorders, obstetric injury | Loss of stool awareness, rectoanal agnosia |

| Fecal impaction | Dyssynergic defecation | Fecal retention with overflow, impaired sensation |

| Altered Stool Characteristics | ||

| Increased volume and loose consistency | Drugs, bile salt malabsorption, infection, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, laxatives, metabolic disorders | Diarrhea and urgency, rapid stool transport, impaired accommodation |

| Hard stools, retention | Drugs, dyssynergia | Fecal retention with overflow |

| Miscellaneous | ||

| Physical mobility, cognitive function | Aging, dementia, disability | Multifactorial changes |

| Psychosis | Willful soiling | Multifactorial changes |

| Drugs* | ||

* Pathophysiology is noted for each class of drugs.

Abnormal Anorectal and Pelvic Floor Structures

Anal Sphincter Muscles

Disruption or weakness of the EAS muscle causes urge-related or diarrhea-associated fecal incontinence. In contrast, damage to the IAS muscle or anal endovascular cushions may lead to a poor seal and an impaired sampling reflex. These changes may cause passive incontinence or fecal seepage (see later), often under resting conditions. Both sphincters may be defective in many patients. The extent of muscle loss can influence the severity of incontinence.13

The most common cause of anal sphincter disruption is obstetric trauma, which may involve the EAS, IAS, or pudendal nerves. Why most women who have sustained an obstetric injury in their 20s or 30s typically do not present with fecal incontinence until their 50s, however, is unclear. In a prospective study, 35% of primiparous (normal antepartum) women showed evidence of anal sphincter disruption after vaginal delivery.28,29 Other important risk factors include a forceps-assisted delivery, prolonged second stage of labor, large birth weight, and occipitoposterior presentation.13 A prospective study of 921 primiparous women has shown that the frequencies of fecal incontinence at 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum are 27% and 17%, respectively, in subjects with vaginal delivery and a sphincter tear; 11% and 8%, respectively, in subjects with vaginal delivery but without a tear; and 10% and 7.6%, respectively, in subjects who underwent cesarean section.30 This study showed clearly that the occurrence and severity of fecal incontinence were attributable to an anal sphincter tear that occurred at the time of vaginal delivery.

Episiotomy is believed to be a risk factor for anal sphincter disruption. In one study, medial episiotomy was associated with a ninefold higher risk of anal sphincter dysfunction.31 Regardless of the type of delivery, however, incontinence of feces or flatus occurred in a surprisingly large percentage of middle-aged women, thereby suggesting that age-related changes in the pelvic floor may predispose to fecal incontinence.

Aging affects anal sphincter function.32 In men and women older than 70 years, sphincter pressures decrease by 30% to 40% compared with younger persons.33 Also, in all age groups, anal squeeze pressure is lower in women than men,33 with a rapid fall after menopause.34 Estrogen receptors have been identified in the human striated anal sphincter, and ovariectomy in rats leads to atrophy of the striated anal sphincter muscle.13,35 These observations suggest that the strength and vigor of the pelvic floor muscles are influenced by hormones. Pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PNTML) is prolonged in older women, and pelvic floor descent is excessive on straining.36 These mechanisms may contribute to progressive damage to the striated anal sphincter muscle. Aging is also associated with increased thickness and echogenicity of the IAS.37

Other causes of anatomic disruption include anorectal surgery for hemorrhoids, fistulas, and fissures. Anal dilation or lateral sphincterotomy may result in incontinence because of fragmentation of the anal sphincters.38 Hemorrhoidectomy can cause incontinence by inadvertent damage to the IAS39 or loss of endovascular cushions. Accidental perineal trauma or a pelvic fracture may also cause direct sphincter trauma that leads to fecal incontinence,40 but anoreceptive intercourse is not associated with anal sphincter dysfunction.41 Finally, IAS dysfunction may also occur because of myopathy, degeneration, or radiotherapy.13

Puborectalis Muscle

The puborectalis muscle is also important for maintaining continence by forming a flap valve mechanism.42 Studies using three-dimensional ultrasound have shown that 40% of women with fecal incontinence have major abnormalities, and another 32% have minor abnormalities of the puborectalis muscle, compared with 21% and 32%, respectively, of asymptomatic parous controls.43 Also, assessment of puborectalis function by a perineal dynamometer revealed impaired puborectalis (levator ani) contraction in patients with fecal incontinence, and this finding was an independent risk factor for and correlated with the severity of fecal incontinence.44 Furthermore, improvement in puborectalis strength following biofeedback therapy was associated with clinical improvement, in part because the upper portion of the puborectalis muscle receives its innervations from branches of the S3 and S4 sacral nerves rather than the pudendal nerve. Therefore, the puborectalis muscle and EAS have separate neurologic innervations. Consequently, pudendal blockage does not abolish voluntary contraction of the pelvic floor45 but completely abolishes EAS function.15

Nervous System

Intact innervation of the pelvic floor is essential for maintaining continence. Sphincter degeneration secondary to pudendal neuropathy and obstetric trauma may cause fecal incontinence in women.28 The neuropathic injury is often sustained during childbirth, probably as a result of stretching of the nerves during elongation of the birth canal or direct trauma during the passage of the fetal head. The nerve damage is more likely to occur when the fetal head is large, the second stage of labor is prolonged, or forceps are applied, especially with a high-forceps delivery or prolonged labor.

The role of extrinsic autonomic innervation is somewhat controversial. Animal studies have shown that the pelvic nerves convey fibers that relax the rectum.46 Consequently, these nerves may play a role in accommodating and storing feces and gas. Damage to the pelvic nerves may lead to impaired accommodation and rapid transit through the rectosigmoid region, thereby overwhelming the continence barrier mechanisms. Sympathetic efferent activity, as studied by stimulating the presacral sympathetic nerves, tends to relax the IAS, whereas parasympathetic stimulation may cause contraction of the anal sphincter. The upper motor neurons for voluntary sphincter muscle lie close to those that innervate the lower limb muscles in the parasagittal motor cortex, adjacent to the sensory representation of the genitalia and perineum in the sensory cortex.13 Consequently, damage to the motor cortex from a central nervous system (CNS) lesion may lead to incontinence. In some patients with neurogenic incontinence, the sensory and motor nerve fibers may be damaged, resulting in sensory impairment.47 This damage can impair conscious awareness of rectal filling as well as the associated reflex responses in the striated pelvic floor sphincter muscles.

Approximately 10% of patients with fecal incontinence may have a lesion more proximal than the intrapelvic or perianal nerves. The primary abnormality in these patients is cauda equina nerve injury,48 which may be occult and not evident through clinical evaluation. These patients have a prolongation of nerve conduction along the cauda equina nerve roots without an abnormality in PNTML.49 In a minority of patients, however, a combination of peripheral and central lesions is present. Other disorders such as multiple sclerosis, diabetes mellitus, and demyelination injury (or toxic neuropathy from alcohol or traumatic neuropathy) may also lead to incontinence.13

Rectum

The rectum is a compliant reservoir that stores stool until social conditions are conducive to its evacuation.2 If rectal wall compliance is impaired, a small volume of stool material can generate a high intrarectal pressure that can overwhelm anal resistance and cause incontinence.50 Causes include radiation proctitis, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn’s disease, infiltration of the rectum by tumor, and radical hysterectomy.51 Similarly, rectal surgery, particularly pouch surgery,52 and spinal cord injury53 may be associated with loss of rectal compliance.

Abnormal Anorectal and Pelvic Floor Function

Impaired Anorectal Sensation

An intact sensation not only provides a warning of imminent defecation, but also helps distinguish among formed stool, liquid feces, and flatus. Older persons,54 those who are physically and mentally challenged, and children with fecal incontinence55 often show blunted rectal sensation. Impaired rectal sensation may lead to excessive accumulation of stool, thereby causing fecal impaction, megarectum (extreme dilatation of the rectum), and fecal overflow. Causes of impaired sensation include neurologic damage such as multiple sclerosis, diabetes mellitus, and spinal cord injury.53 Less well known is that analgesics (particularly opiates) and antidepressants also may impair rectal sensation and produce fecal incontinence. The importance of the rectum in preserving continence has been demonstrated conclusively through surgical studies in which preservation of the distal 6 to 8 cm of the rectum, along with its parasympathetic nerve supply, helped subjects avoid incontinence.56 By contrast, rectal sensation and the ability to defecate can be abolished completely by resection of the nervi erigentes (see earlier).23

An intact sampling reflex allows an individual to choose whether to discharge or retain rectal contents. Conversely, an impaired sampling reflex may predispose a subject to incontinence.25 The role of the sampling reflex in maintaining continence, however, remains unclear. In children who have undergone colonic pull-through surgery (see Chapter 113), some degree of sensory discrimination is preserved.57 Because the anal mucosal sensory zone is absent in these children, the suggestion has been made that sensory receptors, possibly located in the puborectalis muscle, may play a role in facilitating sensory discrimination. Also, traction on the muscle is a more potent stimulus for triggering defecation and a sensation of rectal distention. Because abolition of anal sensation by the topical application of 5% lidocaine does not reduce resting sphincter pressure (although it affects voluntary squeeze pressure but does not affect the ability to retain saline infused into the rectum), the role of anal sensation in maintaining fecal continence has been questioned.13

Dyssynergic Defecation and Incomplete Stool Evacuation

In some patients, particularly older adults, prolonged retention of stool in the rectum or incomplete evacuation may lead to seepage of stool or staining of undergarments.54 Most of these patients show obstructive or dyssynergic defecation,58 and many of them also exhibit impaired rectal sensation, whereby anal sphincter and pudendal nerve function is intact but the ability to evacuate a simulated stool is impaired. Similarly, in older adults and in children with functional incontinence, the prolonged retention of stool in the rectum can lead to fecal impaction. Fecal impaction may also cause prolonged relaxation of the IAS, thereby allowing liquid stool to flow around impacted stool and to escape through the anal canal (see Chapter 18).55

Descending Perineum Syndrome

In women with long-standing constipation and a history of excessive straining for many years (perhaps even without prior childbirth), excessive straining may lead to progressive denervation of the pelvic floor muscles.59 Most of these patients demonstrate excessive perineal descent and sphincter weakness, which may lead to rectal prolapse; however, fecal incontinence is not an inevitable consequence. Whether or not incontinence develops will depend on the state of the pelvic floor and the strength of the sphincter muscles.

Altered Stool Characteristics

The consistency, volume, and frequency of stool and the presence or absence of irritants in stool also may play a role in the pathogenesis of fecal incontinence.2 In the presence of large-volume liquid stools, which often transit the hindgut rapidly, continence can only be maintained through intact sensation and a strong sphincteric barrier. Similarly, in patients with bile salt malabsorption, lactose or fructose intolerance, or rapid dumping of osmotic material into the colon, colonic transit of gaseous and stool contents is too rapid and can overwhelm the continence mechanisms (see Chapters 15 and 101).2

Miscellaneous Mechanisms

Various medical conditions and disabilities may predispose to fecal incontinence, particularly in older adults. Immobility and lack of access to toileting facilities are primary causes of fecal incontinence in this population.60 Several drugs may inhibit sphincter tone. Some are used to treat urinary incontinence and detrusor instability, including anticholinergics such as tolterodine tartarate (Detrol) and oxybutynin (Ditropan) and muscle relaxants such as baclofen (Lioresal), and cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril). Stimulants such as caffeinated products, fiber supplements, or laxatives may produce fecal incontinence by causing diarrhea.13

EVALUATION

CLINICAL FEATURES

The first step in the evaluation of a patient with fecal incontinence is to establish a trusting relationship with the patient and assess the duration and nature of the symptoms, with specific attention to whether the leakage consists of flatus, liquid stool, or solid stool and to the impact of the symptoms on the quality of the patient’s life (Table 17-2). Because many people misinterpret fecal incontinence as diarrhea or urgency,61 a detailed characterization of the symptom(s) is important. The clinician should ask about the use of pads or other devices and the patient’s ability to discriminate between formed or unformed stool and gas (the lack of such discrimination is termed rectal agnosia).2 An obstetric history; history of coexisting conditions such as diabetes mellitus, pelvic radiation, neurologic problems, or spinal cord injury; dietary history; and history of coexisting urinary incontinence are important. A prospective stool diary can be useful. The circumstances under which incontinence occurs should also be determined. Such a detailed inquiry may facilitate the recognition of the following types of fecal incontinence:

Table 17-2 Features of the History That Should Be Elicited from a Patient with Fecal Incontinence

Although overlap exists among these three types, by determining the predominant pattern, useful insights can be gained regarding the underlying mechanism(s) and preferred management. Symptom assessment, however, may not correlate well with manometric findings (see later). In one study, leakage had a sensitivity of 98.9%, specificity of 11%, and positive predictive value of 51% for detecting a low resting anal sphincter pressure on manometry.62 The positive predictive value for detecting a low anal squeeze pressure was 80%. Therefore, for an individual patient with fecal incontinence, the history and clinical features alone are insufficient to define the pathophysiology, and objective testing is essential63,64 (see later).

On the basis of the clinical features, several grading systems have been proposed. A modification of the Cleveland Clinic grading system65 has been validated by the St. Mark’s investigators66 and provides an objective method of quantifying the degree of incontinence. It can also be useful for assessing the efficacy of therapy. This grading system is based on seven parameters that include the following: (1-3) the character of the anal discharge as solid, liquid, or flatus; (4) the degree of alterations in lifestyle; (5, 6) the need to wear a pad or take antidiarrheal medication; and (7) the ability to defer defecation. The total score ranges from 0 (continent) to 24 (severe incontinence). As noted earlier, however, clinical features alone are insufficient to define the pathophysiology. The use of validated questionnaires such as the SCL-90R (Symptom Checklist-90-R) and SF-36 (Short-Form 36) surveys may provide additional information regarding psychosocial issues and the impact of fecal incontinence on the patient’s quality of life.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A detailed physical examination, including a neurologic examination, should be performed in any patient with fecal incontinence, because incontinence may be secondary to a systemic or neurologic disorder. The focus of the examination is on the perineum and anorectum. Perineal inspection and digital rectal examination are best performed with the patient lying in the left lateral position and with good illumination. On inspection, the presence of fecal matter, prolapsed hemorrhoids, dermatitis, scars, skin excoriations, or a gaping anus and the absence of perianal creases may be noted. These features suggest sphincter weakness or chronic skin irritation and provide clues regarding the underlying cause.2 Excessive perineal descent or rectal prolapse can be demonstrated by asking the patient to attempt defecation. An outward bulge that exceeds 3 cm is usually defined as excessive perineal descent (see Chapter 18).67

Perianal sensation should be checked. The anocutaneous reflex examines the integrity of the connections between the sensory nerves and the skin; the intermediate neurons in spinal cord segments S2, S3, and S4; and the motor innervation of the external anal sphincter. This reflex can be assessed by gently stroking the perianal skin with a cotton bud in each perianal quadrant. The normal response consists of a brisk contraction of the external anal sphincter (“anal wink”). An impaired or absent anocutaneous reflex suggests either afferent or efferent neuronal injury.2

The accuracy of the digital rectal examination has been assessed in several studies. In one study of 66 patients, digital rectal examination by an experienced surgeon correlated somewhat with resting sphincter pressure (r = 0.56; P < 0.001) or maximum squeeze pressure (r = 0.72; P < 0.001).68 In a study of 280 patients with various anorectal disorders, a reasonable correlation was reported between digital examination and manometric findings, but the sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive values of digital examination were low.69 In another study of 64 patients, the agreement between digital rectal examination and resting or squeeze pressure was 0.41 and 0.52, respectively.70 These data suggest that digital rectal examination provides only an approximation of sphincter strength. The findings are influenced by many factors, including the size of the examiner’s finger, technique used, and cooperation of the patient. One study has shown that trainees lack adequate skills for recognizing the features of fecal incontinence on digital rectal examination.71 Therefore, digital rectal examination is not reliable and is prone to interobserver differences. Digital rectal examination can identify patients with fecal impaction and overflow but is not accurate for diagnosing sphincter dysfunction and should not be used as the basis for decisions regarding treatment.2

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

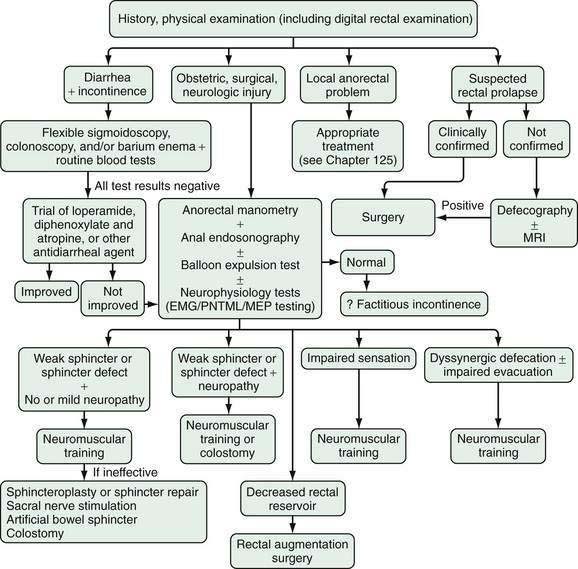

The first step in assessing a patient with fecal incontinence is to determine whether the incontinence is secondary to diarrhea or independent of stool consistency. If diarrhea coexists with incontinence, appropriate tests should be performed to identify the cause of the diarrhea (see Chapter 15). Such testing may include flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy to exclude colonic mucosal inflammation, a rectal mass, or stricture and stool studies for infection, volume, osmolality, electrolytes, fat content, and pancreatic function. Biochemical tests should be performed to look for thyroid dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, and other metabolic disorders. Breath tests may be considered for lactose or fructose intolerance or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.2 A history of cholecystectomy may suggest bile salt malabsorption and prompt a therapeutic trial of a bile salt–binding agent.

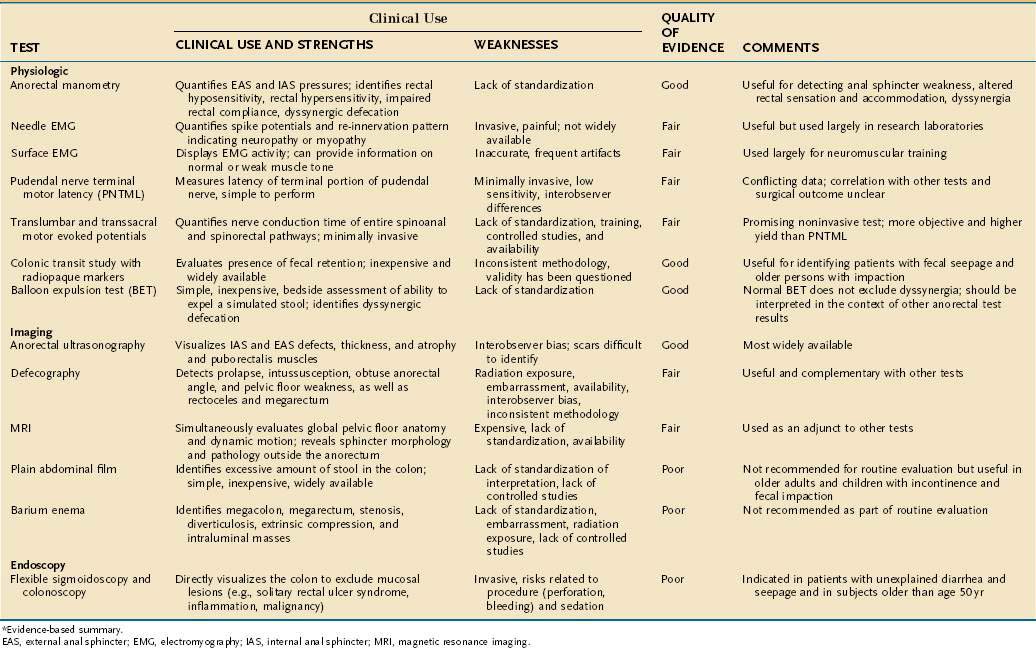

Specific tests are available for defining the underlying mechanisms of fecal incontinence and are often used in complementary fashion. The most useful tests are anorectal manometry, anal endosonography, the balloon expulsion test, and PNTML.2,72–74

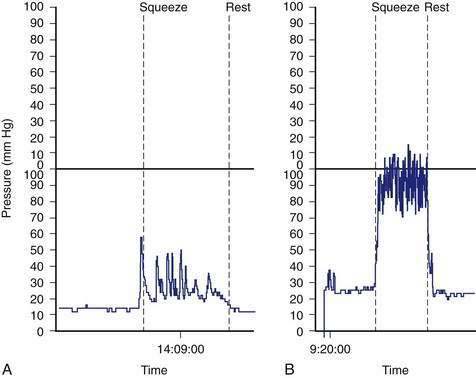

Anorectal Manometry and Sensory Testing

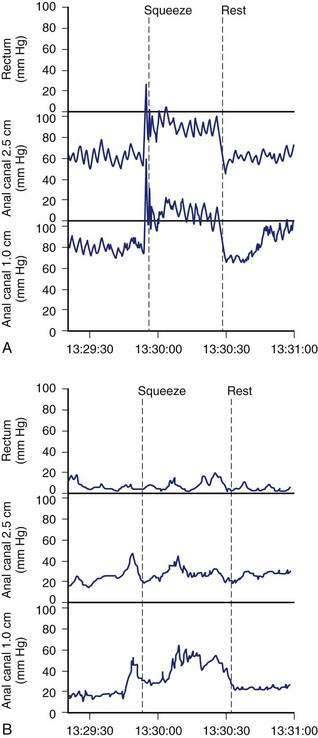

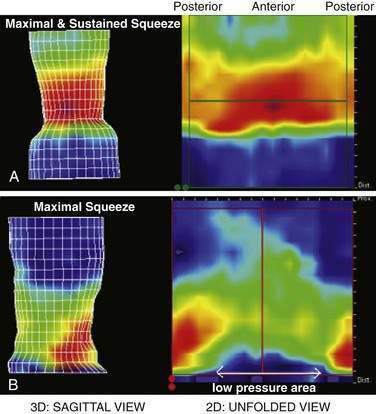

Anorectal manometry is a simple and useful method for assessing IAS and EAS pressures (Fig. 17-3) as well as rectal sensation, rectoanal reflexes, and rectal compliance. Several types of probes and pressure recording devices are available. Each system has distinct advantages and drawbacks. A water-perfused probe with multiple closely spaced sensors is commonly used.2 Increasingly, a solid-state probe with microtransducers or air-filled miniaturized balloons is used. A novel solid-state probe with 36 circumferential sensors spaced at 1-cm intervals, with a 4.2-mm outer diameter (Sierra Scientific Instruments, Los Angeles) has been reported to provide higher resolution than older style probes.75 This device uses a novel pressure transduction technology (TactArray) that allows each of the 36 pressure sensing elements to detect pressure over a length of 2.5 mm and in each of 12 radially dispersed sectors. The data can be displayed in isobaric contour plots that can provide a continuous dynamic representation of pressure changes, although anal sphincter pressures are higher than those recorded with water-perfused manometry. A high-definition manometry system with 256 circumferentially arrayed sensors in a 5-cm probe76 has become available and may provide anal sphincter pressure profiles and topographic changes of even higher fidelity (Fig. 17-4).

Anal sphincter pressures can be measured by stationary or station pull-through techniques.73,74 Resting anal sphincter pressure predominantly represents IAS function, and voluntary anal squeeze pressure predominantly represents EAS function. Patients with fecal incontinence have low resting and low squeeze pressures (see Figs. 17-3 and 17-4), indicating IAS and EAS weakness.2,69 The duration of sustained squeeze pressure provides an index of sphincter muscle fatigue. The ability of the EAS to contract reflexively can be assessed during abrupt increases in intra-abdominal pressure, as when the patient coughs. This reflex response causes the anal sphincter pressure to rise above that of the rectal pressure to preserve continence. The response may be triggered by receptors in the pelvic floor and mediated through a spinal reflex arc. In patients with a spinal cord lesion above the conus medullaris, this reflex response is preserved, even though voluntary squeeze may be absent, whereas in patients with a lesion of the cauda equina or sacral plexus, both the reflex and voluntary squeeze responses are absent.2,77,78

Rectal Sensory Testing

Rectal balloon distention with air or water can be used to assess sensory responses and compliance of the rectal wall. By distending a balloon in the rectum with incremental volumes, the thresholds for first perception, first desire to defecate, and urgent desire to defecate can be assessed. A higher threshold for sensory perception indicates reduced rectal sensitivity.2,77,79 The balloon volume required for partial or complete inhibition of anal sphincter tone also can be assessed. The volume required to induce reflex anal relaxation is lower in incontinent patients than in controls.80

Because sampling of rectal contents by the anal mucosa may play an important role in maintaining continence,25 quantitative assessment of anal perception using electrical or thermal stimulation has been advocated but is not used clinically.2 Rectal compliance can be calculated by assessing the changes in rectal pressure during balloon distention with air or fluid.73,81 Rectal compliance is reduced in patients with colitis,50 patients with a low spinal cord lesion, and diabetic patients with incontinence but is increased in those with a high spinal cord lesion.

Anorectal manometry can provide useful information regarding anorectal function.72,73,82 The American Motility Society has provided consensus guidelines and minimal standards for manometry testing.74 Although there are insufficient data regarding normal values, overlap betwen healthy subjects and patients with fecal incontinence,69 and large confidence intervals for test reproducibility,83 manometry testing can be useful for the individual patient with fecal incontinence.74 Manometric tests of anorectal function may also be useful for assessing objective improvement following drug therapy, biofeedback therapy, or surgery.84–86

Imaging the Anal Canal

Anal Endosonography

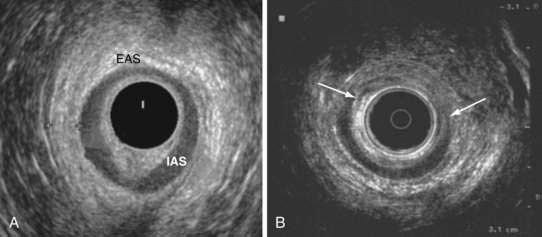

Anal endosonography is performed by using a 7- to 15-mHz rotating transducer with a focal length of 1 to 4 cm.87 The test provides an assessment of the thickness and structural integrity of the EAS and IAS and can detect scarring, loss of muscle tissue, and other local pathology (Fig. 17-5).88 Higher frequency (10- to 15-mHz) probes that provide better delineation of the sphincter complex have become available.88

After vaginal delivery, anal endosonography has revealed occult sphincter injury in 35% of primipara women; most of these lesions were not detected clinically. In another study, sphincter defects were detected in 85% of women with a third-degree perineal tear compared with 33% of subjects without a tear.89 In studies that compared electromyography (EMG; see later) mapping with anal endosonography, the concordance rate for identifying a sphincter defect was high.90,91 The technique is, however, operator-dependent and requires training and experience.73 Although endosonography can distinguish internal from external sphincter injury, it has a low specificity for demonstrating the cause of fecal incontinence.2 Because anal endosonography is more widely available, less expensive, and certainly less painful than EMG, which requires needle insertion, it is the preferred technique for examining the morphology of the anal sphincter muscles.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Endoanal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been shown to provide superior imaging with excellent spatial resolution, particularly for defining the anatomy of the EAS.92,93 One study,94 but not another,92 has shown that MRI is less accurate than anal endosonography. A major contribution of anal MRI has been the recognition of external sphincter atrophy, which may adversely affect sphincter repair95 (see later). Atrophy also may be present without pudendal neuropathy.96 The addition of dynamic pelvic MRI using fast imaging sequences or MRI colpocystography, which involves filling the rectum with ultrasound gel as a contact agent and having the patient evacuate while lying inside the magnet, may define the anorectal anatomy more precisely.97 The use of an endoanal coil significantly enhances the resolution and allows more precise definition of the sphincter muscles. Comparative studies of costs, availability, technical factors, clinical utility, and role in treatment decision making are warranted.

Defecography

Defecography uses fluoroscopic techniques to provide morphologic information about the rectum and anal canal.98 It is used to assess the anorectal angle, measure pelvic floor descent and length of anal canal, and detect the presence of a rectocele, rectal prolapse, or mucosal intussusception. Approximately 150 mL of contrast material is placed into the rectum, and the subject is asked to squeeze or cough and expel the contrast. Although defecography can detect a number of abnormalities, these abnormalities can also be seen in otherwise asymptomatic persons,73,99 and their presence correlates poorly with impaired rectal evacuation. Agreement between observers in the measurement of the anorectal angle is also poor. Whether one should use the central axis of the rectum or the posterior wall of the rectum when measuring the angle is unclear. The functional significance of identifying morphologic defects has been questioned. Although defecography can confirm the occurrence of incontinence at rest or during coughing, it is most useful for demonstrating rectal prolapse2,100 or poor rectal evacuation (see Chapter 18). In selected patients, magnetic resonance defecography may evaluate evacuation and identify coexisting problems such as a rectocele, enterocele, cystocele, or mucosal intussusception.88

Balloon Expulsion Test

Normal subjects can expel a 50-mL water-filled balloon101 or a silicone-filled artificial stool from the rectum in less than one minute.2 Most patients with fecal incontinence have little or no difficulty with evacuation, but patients with fecal seepage58 and many older persons with fecal incontinence secondary to fecal impaction54 demonstrate impaired evacuation. In these patients, a balloon expulsion test may help identify coexisting dyssynergia or a lack of coordination between the abdominal, pelvic floor, and anal sphincter muscles during defecation. One study has shown a high frequency of dyssynergia in residents of nursing homes (see Chapter 18).102

Neurophysiologic Testing

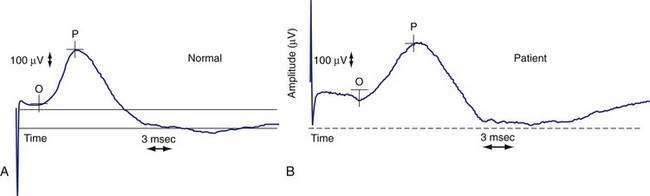

Electrical recording of the muscle activity from the anal sphincter (EMG) is a useful technique for identifying sphincter injury as well as denervation-reinnervation potentials that can indicate neuropathy.22,73 EMG can be performed using a fine wire needle electrode or a surface electrode, such as an anal plug. Abnormal EMG activity, such as fibrillation potentials and high-frequency spontaneous discharges, provides evidence of chronic denervation, which commonly is seen in patients with fecal incontinence secondary to pudendal nerve injury or cauda equina syndrome.103 The PNTML measures the neuromuscular integrity between the terminal portion of the pudendal nerve and the anal sphincter. Injury to the pudendal nerve leads to denervation of the anal sphincter muscle and muscle weakness. Therefore, measurement of the nerve latency time can help distinguish muscle injury from nerve injury as the cause of a weak sphincter muscle. A disposable electrode (St. Mark’s electrode; Dantec, Denmark) is used to measure the latency time.104 A prolonged nerve latency time suggests pudendal neuropathy (Fig. 17-6).

Women who have delivered vaginally with a prolonged second stage of labor or have had forceps-assisted delivery have been found to have a prolonged PNTML compared with women who delivered by cesarean section or spontaneously.105,106 An American Gastroenterological Association technical review did not recommend PNTML,73 although an expert review has noted that patients with pudendal neuropathy generally have a poor surgical outcome.107 A normal PNTML does not exclude pudendal neuropathy, because the presence of a few intact nerve fibers can lead to a normal result, whereas an abnormal latency time is significant. PNTML may be useful in the assessment of patients prior to anal sphincter repair and is particularly helpful in predicting the outcome of surgery.

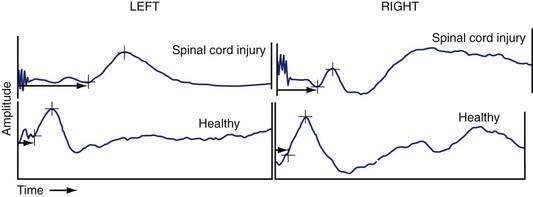

The integrity of the peripheral component of efferent motor pathways that control anorectal function can also be assessed by recording the motor evoked potentials (MEPs) of the rectum and anal sphincter in response to magnetic stimulation of the lumbosacral nerve roots (translumbar magnetic stimulation [TLMS] and transsacral magnetic stimulation [TSMS]).22,108,109 The technique is based on Faraday’s principle, which states that in the presence of a changing electrical field, a magnetic field is generated. Consequently, when a current is discharged rapidly through a conducting coil, a magnetic flux is produced around the coil. The magnetic flux causes stimulation of neural tissue. Magnetic stimulation of the lumbosacral roots (TLMS and TSMS) may allow more precise localization of the motor pathways between the brain and the anal sphincter as well as subcomponent analysis of the efferent nervous system between the brain and sphincter. Electrical or magnetic stimulation of the lumbosacral nerve roots facilitates measurement of the conduction time within the cauda equina and can diagnose sacral motor radiculopathy as a possible cause of fecal incontinence.110,111 One study has shown that translumbar MEP and transsacral MEP of the rectum and anus provides delineation of peripheral neuromuscular injury in subjects with fecal incontinence108 (Fig. 17-7) and can reveal hitherto undetected changes in patients with back injury.

Saline Infusion Test

The saline infusion test assesses the overall capacity of the defecation unit to maintain continence during conditions that simulate diarrhea.72,80,82 With the patient lying on the bed, a 2-mm plastic tube is introduced approximately 10 cm into the rectum and taped in position. Next, the patient is transferred to a commode. The tube is connected to an infusion pump and 800 mL of warm saline (37°C) is infused into the rectum at a rate of 60 mL/min. The patient is instructed to hold the liquid for as long as possible. The volume of saline infused at the onset of first leak (defined as a leak of at least 15 mL) and the total volume retained at the end of infusion are recorded. Most normal subjects should retain most of the infused volume without leakage, whereas patients with fecal incontinence or patients with impaired rectal compliance, such as those with ulcerative colitis,112 leak at much lower volumes. The test is also useful for assessing objective improvement of fecal incontinence after biofeedback therapy.85

Clinical Utility of Tests for Fecal Incontinence

In one prospective study, history taking alone could detect an underlying cause in only 9 of 80 patients (11%) with fecal incontinence, whereas physiologic tests revealed an abnormality in 44 patients (55%).113 In a large retrospective study of 302 patients with fecal incontinence, an underlying pathophysiologic abnormality was identified, but only after manometry, EMG, and rectal sensory testing were performed.114 Most patients had more than one pathophysiologic abnormality.

In another large study of 350 patients, incontinent patients had lower resting and squeeze sphincter pressures, a smaller rectal capacity, and earlier leakage following saline infusion in the rectum.82 Nevertheless, results of a single test or a combination of three different tests (anal manometry, rectal capacity, saline continence test) provided a low discriminatory value between continent and incontinent patients. This finding emphasizes the wide range of normal values and the ability of the body to compensate for the loss of any one mechanism involved in fecal incontinence.

In a prospective study, anorectal manometry with sensory testing not only confirmed a clinical impression, but also provided new information that was not detected clinically.72 Furthermore, the diagnostic information obtained from these studies can influence both the management and outcome of patients with incontinence. A single abnormality was found in 20% of patients, whereas more than one abnormality was found in 80% of patients. In another study, abnormal sphincter pressure was found in 40 patients (71%), whereas altered rectal sensation or poor rectal compliance was present in 42 patients (75%).113 These findings were confirmed by another study, which showed that physiologic tests provided a definitive diagnosis in 66% of patients with fecal incontinence.114 Still, on the basis of the test results alone, it is not possible to predict whether an individual patient is continent or incontinent. Consequently, an abnormal test result must be interpreted in the context of the patient’s symptoms and the results of other complementary tests. Tests of anorectal function provide objective data and define the underlying pathophysiology. Table 17-3 summarizes the key tests, information gained from them, and evidence to support their clinical use.

TREATMENT

The goal of treatment for patients with fecal incontinence is to restore continence and improve their quality of life. Strategies that include supportive and specific measures may be used. An algorithmic approach to the evaluation and management of patients with fecal incontinence is presented in Figure 17-8.

SUPPORTIVE MEASURES

Supportive measures such as avoiding offending foods, ritualizing bowel habit, improving skin hygiene, and instituting lifestyle changes may serve as useful adjuncts to the management of fecal incontinence. Obtaining a comprehensive history (see Table 17-1), performing a detailed physical examination, and requesting that the patient keep a prospective stool diary2,73 can provide important clues regarding the severity and type of incontinence as well as predisposing conditions, such as fecal impaction, dementia, neurologic disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or dietary factors (e.g., carbohydrate intolerance). If present, these conditions should be treated or corrected.

In the management of older or institutionalized patients with fecal incontinence, the availability of personnel experienced in the treatment of fecal incontinence, timely recognition of soiling, and immediate cleansing of the perianal skin are of paramount importance.60 Hygienic measures such as changing undergarments, cleaning the perianal skin immediately following a soiling episode, use of moist tissue paper (baby wipes) rather than dry toilet paper, and use of barrier creams such as zinc oxide and calamine lotion (Calmoseptine; Calmoseptine, Huntington Beach, Calif) may help prevent skin excoriation. Perianal fungal infections should be treated with topical antifungal agents. More importantly, scheduled toileting with a commode at the bedside or bedpan and supportive measures to improve the general well-being and nutritional status of the patient may prove effective. Stool deodorants (e.g., Bedside Care Perineal Wash, Minneapolis; Derifil, Integra, Plainsboro, NJ; Devrom, Parthenon, Salt Lake City) can help disguise the smell of feces. In an institutionalized patient, ritualizing the bowel habit and instituting cognitive training may prove beneficial. Using these measures, short-term (3- to 6-month) success rates of up to 60% have been reported in case series.115 Patients in whom these measures fail have been shown to have a higher mortality rate than those without incontinence and than those with incontinence who respond to these measures.116

Other supportive measures include dietary modifications, such as reducing caffeine or fiber intake. Caffeine-containing coffee enhances the gastrocolic (or gastroileal) reflex, increases colonic motility,117 and induces fluid secretion in the small intestine.118 Therefore, reducing caffeine consumption, particularly after meals, may help lessen postprandial urgency and diarrhea. Brisk physical activity, particularly after meals or immediately after waking, may precipitate fecal incontinence because these physiologic events are associated with increased colonic motility.119 Acute exercise can enhance colonic motor activity and transit.120 A food and symptom diary may identify dietary factors that cause diarrheal stools and incontinence; frequent culprits are lactose and fructose, which may be malabsorbed.121 Eliminating food items containing these constituents may prove beneficial.2 Fiber supplements such as psyllium are often advocated in an attempt to increase stool bulk and reduce watery stools. In a single case-controlled study, psyllium led to a modest improvement,122 but fiber supplements can potentially worsen diarrhea by increasing colonic fermentation of unabsorbable fiber.

SPECIFIC THERAPIES

Pharmacologic Therapy

The antidiarrheal agents loperamide hydrochloride (Imodium) and diphenoxylate and atropine sulfate (Lomotil ) remain the mainstays of drug treatment for fecal incontinence, although other drug treatments have been proposed.2,123 In placebo-controlled studies, loperamide, 4 mg three times daily, has been shown to reduce the frequency of incontinence, improve stool urgency, and increase colonic transit time,84 as well as increase anal resting sphincter pressure124 and reduce stool weight. Clinical improvement was also reported with diphenoxylate and atropine,125 but objective testing showed no improvement in the ability of the patient to retain saline or spheres in the rectum. Although most patients benefit from antidiarrheal agents temporarily, many report cramping, lower abdominal pain, or difficulty with evacuation after a few days. Therefore, careful titration of the dose is required to produce the desired result.

Idiopathic bile salt malabsorption may be an important underlying cause of diarrhea and fecal incontinence (see Chapter 15).126 Patients with this problem may benefit from titrated doses of ion exchange resins such as cholestyramine (Questran) or colestipol (Colestid). Alosetron (Lotronex), a 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor antagonist used for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome and diarrhea, may serve as an adjunct to the therapy of fecal incontinence, but use of the drug is restricted because of side effects (see Chapter 118).127

Postmenopausal women with fecal incontinence may benefit from estrogen replacement therapy.128 An open-labeled study has shown that oral amitriptyline, 20 mg, is useful in the treatment of patients with urinary or fecal incontinence without evidence of a structural defect or neuropathy.129 Suppositories or enemas may also have a role in the treatment of incontinent patients with incomplete rectal evacuation or in those with postdefecation seepage. In some patients, constipating medications alternating with periodic enemas may provide more controlled evacuation of bowel contents, but these interventions have not been tested prospectively.

Neuromuscular Training

Neuromuscular training, usually referred to as biofeedback therapy, improves symptoms of fecal incontinence, restores quality of life, and improves objective parameters of anorectal function. Biofeedback training is useful in patients with a weak sphincter or impaired rectal sensation. The method is based on operant conditioning techniques whereby an individual acquires a new behavior through a learning process of repeated reinforcement and instant feedback.2,130 The goals of neuromuscular training in a patient with fecal incontinence are as follows: (1) to improve the strength of the anal sphincter muscles; (2) to improve the coordination between the abdominal, gluteal, and anal sphincter muscles during voluntary squeeze and following rectal perception; and (3) to enhance anorectal sensory perception.

Because each goal requires a specific method of training, the treatment protocol should be customized for each patient on the basis of the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism(s). Neuromuscular training often is performed using visual, auditory, or verbal feedback techniques, and the feedback is provided by a manometry or EMG probe placed in the anorectum.2,130 When a patient is asked to squeeze, the anal sphincter contraction is displayed as an increase in anal pressure or EMG activity. This visual cue provides instant feedback to the patient.

The aim of rectoanal coordination training is to achieve a maximum voluntary squeeze in less than two seconds after a balloon is inflated in the rectum. In reality, this maneuver mimics the arrival of stool in the rectum and prepares the patient to react appropriately by contracting the right group of muscles.2,130 Patients are taught how to squeeze their anal muscles selectively without increasing intra-abdominal pressure or inappropriately contracting their gluteal or thigh muscles. Also, this maneuver identifies sensory delay and trains the individual to use visual clues to improve sensorimotor coordination.131,132 Sensory training of the rectum educates the patient to perceive a lower volume of balloon distention but with the same intensity as they had felt earlier with a higher volume. This goal is achieved by repeatedly inflating and deflating a balloon in the rectum.

Predicting how many neuromuscular treatment sessions will be required is often difficult. Most patients seem to require between four and six training sessions (Fig. 17-9).2,85,130 Studies that used a fixed number of treatment sessions, often less than three, showed a less favorable improvement response than those that titrated the number of sessions on the basis of the patient’s performance.133,134 In one study, periodic reinforcement with neuromuscular training at six weeks, three months, and six months was thought to confer additional benefit85 and long-term improvement.135

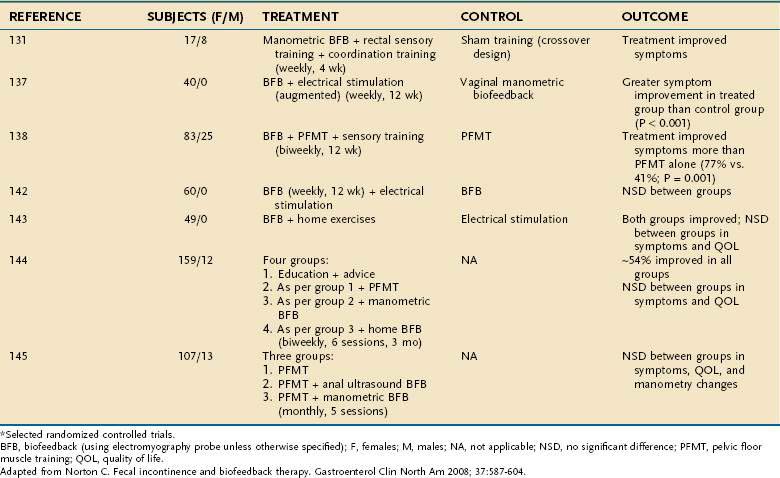

In the literature on fecal incontinence,136–146 the terms improvement, success, or cure have been used interchangeably, and the definition of each term has been inconsistent. In uncontrolled studies, subjective improvement has been reported in 40% to 85% of patients.2,133 Table 17-4 summarizes selected randomized controlled trials of neuromuscular training in patients with fecal incontinence.130,131,137,138,142–145 A Cochrane review of 11 randomized, controlled trials has concluded that no method of training is better than any other method.147 Whether biofeedback is superior to conservative management is also unclear. In the most recent randomized controlled trial,138 108 patients were randomized to receive either six sessions of EMG biofeedback (n = 44) or Kegel exercises (n = 64) plus supportive therapy. After treatment, 77% of patients who received biofeedback reported adequate relief of symptoms compared with 41% of those who did Kegel exercises (P < 0.001). The number of episodes of incontinence was not different between groups in an intention-to-treat analysis, but a trend toward improvement (P = 0.042) was observed in a per-protocol analysis.138 This study suggests that biofeedback is superior to Kegel exercises.

Table 17-4 Outcome of Neuromuscular Training (Biofeedback Therapy) and/or Exercises for Fecal Incontinence in Adults*

The technique of neuromuscular training has not been standardized, and the use of this treatment is largely restricted to specialized centers. The manometric parameters obtained at baseline do not appear to predict the clinical response to biofeedback treatment.148 Similarly, the patient’s age, presence of sphincter defects, or presence of neuropathy do not predict outcome.149 Therefore, criteria used for selection, motivation of the individual patient, enthusiasm of the therapist, and severity of incontinence each may affect the outcome.2,130,133,134,144

Despite the lack of a uniform approach and the inconsistencies in the reported outcomes of randomized controlled trials, neuromuscular training seems to confer benefit (see Table 17-4). Therefore, neuromuscular training should be offered to all patients with fecal incontinence who have failed supportive measures and especially to older patients, patients with comorbid illnesses, and those for whom reconstructive surgery is being considered. Severe fecal incontinence, pudendal neuropathy, and an underlying neurologic disorder are associated with a poor response to biofeedback therapy.150–152 One study has suggested that neuromuscular training may be most beneficial in patients with urge incontinence.153 Biofeedback also seems to be useful for patients who have undergone anal sphincteroplasty,154 postanal repair (see later),155 or low-anterior resection156 and children who have undergone correction of a congenital anorectal anomaly.157

Plugs, Sphincter Bulkers, and Electrical Stimulation

Disposable anal plugs have been used to help occlude the anal canal temporarily.158 Unfortunately, many patients are unable to tolerate prolonged insertion of the device.159,160 A plug may be useful for patients with impaired anal canal sensation, those with neurologic disease,161 and those who are institutionalized or immobilized. In some patients with fecal seepage, insertion of an anal plug made of cotton wool may prove beneficial162; the recommended wear time (although not formally tested) is up to 12 hours.130 Diapers generally are thought to be unsatisfactory for providing security or comfort, protecting the skin, or disguising odor. Many people with fecal incontinence choose not to wear a pad. Small anal dressings may be useful for people with minor soiling contained between the buttocks but can become costly if several dressings are needed each day.

Bulking the anal sphincter to augment its surface area and thereby provide a better seal for the anal canal has been attempted with a variety of agents, including autologous fat,163 glutaraldehyde-treated collagen,164 and synthetic macromolecules.165 These materials usually are injected submucosally at the site where the sphincter is deficient or circumferentially if the whole muscle is degenerated or fragmented. Studies have shown definite improvement in the short term in patients with passive fecal incontinence. The experience with these techniques, however, is limited, and controlled and long-term outcome studies have not been done. Newer and better designed anal plugs are currently being tested.

Electrical stimulation of striated muscle at a frequency sufficient to produce a tonic involuntary contraction (usually 30 to 50 Hz) can increase muscle strength, conduction rate of the pudendal nerve, and size of motor units, encourage neuronal sprouting, and promote local blood flow.166,167 Stimulation at lower frequencies (typically 5 to 10 Hz) can modulate autonomic function, including sensation and overactivity. Studies of electrical stimulation for fecal incontinence, however, generally have been small and uncontrolled and have been confounded by the effects of exercise, biofeedback, or other interventions. A Cochrane review of four randomized controlled trials with 260 participants concluded that electrical stimulation may have some effect.168 One study has found that anal electrical stimulation with anal biofeedback produces short-term benefits greater than those with biofeedback alone,137 whereas another study found no additional benefit to electrical stimulation over exercises and biofeedback alone.142 Also, patients have been shown to improve equally with stimulation at 1 and 35 Hz.130 Two randomized controlled trials have reported that biofeedback and electrical stimulation are equally effective.169,170 Therefore, whether electrical stimulation by itself is helpful remains unclear.

Surgical Therapy

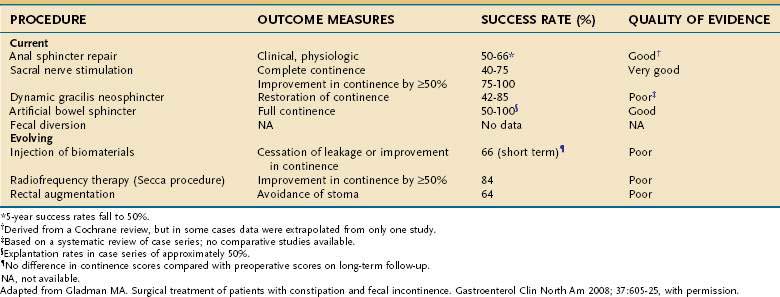

Surgery should be considered for selected patients who have failed conservative measures or biofeedback therapy. The choice of surgical procedure must be tailored to the need of the individual patient and can be described under four broad clinical categories: (1) simple structural defects of the anal sphincters; (2) weak but intact anal sphincters; (3) complex disruption of the anal sphincter complex; and (4) extrasphincteric abnormalities. Table 17-5 summarizes success rates for these surgical procedures.171

In most subjects, particularly those with obstetric trauma, overlapping sphincter repair is often sufficient. The torn ends of the sphincter muscle are plicated together and to the puborectalis muscle. Overlapping sphincter repair, as described by Parks and McPartlin,172 involves a curved incision anterior to the anal canal with mobilization of the external sphincter, which is divided at the site of the scar; the scar tissue is preserved to anchor the sutures, and overlap repair is carried out using two rows of sutures. If an internal anal sphincter defect is identified, a separate imbrication (overlapping repair) of the internal anal sphincter may be undertaken. Symptom improvement with a frequency in the range of 70% to 80% has been reported, although one study reported an improvement rate of only approximately 50%.172–176 Furthermore, some patients may experience problems with evacuation after surgery.

In patients with incontinence caused by a weak but intact anal sphincter, postanal repair has been tried.177 The anorectal angle is made more acute via an intersphincteric approach, thereby improving continence. The long-term success of this approach ranges from 20% to 58%.178

In patients with severe structural damage of the anal sphincter and significant incontinence, construction of a neosphincter has been attempted using two approaches: (1) use of autologous skeletal muscle, often the gracilis and rarely the gluteus107,179; and (2) use of an artificial bowel sphincter (ABS).180 The technique of stimulated gracilis muscle transposition (dynamic graciloplasty) has been tested in many centers.181,182 This technique uses the principle that a fast-twitch, fatigable skeletal muscle, when stimulated over a long period of time, can be transformed into a slow-twitch fatigable muscle that can provide a sustained, sphincter-like muscle response. Such continuous stimulation is maintained by an implanted pacemaker. When the subject has to defecate or expel gas, an external magnetic device is used to switch off the pacemaker temporarily. Rates of clinical improvement with this approach have ranged from 38% to 90% (mean 67%).171 The other approach to neosphincter construction has been to implant an ABS. The ABS consists of an implanted inflatable cuffed device that is filled with fluid from an implanted balloon reservoir, which is controlled by a subcutaneous pump. The cuff is deflated to allow defecation. In one series of 24 carefully selected patients, almost 75% reported satisfactory results, although some had the device explanted.183 Both approaches (dynamic graciloplasty and ABS) require major surgery and are associated with revision rates that approach 50%. At medium-term follow up, 50% to 70% of patients have a functioning new sphincter. Several groups have reported their experiences with the ABS in small numbers of patients with overall improvement in continence in approximately 50% to 75% of patients.184,185 A randomized controlled trial has demonstrated that ABS is better than conservative treatment in improving continence.186 Long-term outcome studies, with median follow-up periods of approximately seven years, however, have documented success rates of less than 50%, explantation rates as high as 49%, and infection rates of up to 33%.131,187 Additionally, evacuation problems occur in 50% of patients.

Rectal augmentation is a novel approach to correct the physiologic abnormalities in a subgroup of patients with intractable fecal incontinence secondary to reservoir or rectal sensorimotor dysfunction.188 Candidates have low rectal compliance and heightened rectal sensation (rectal hypersensitivity). The procedure involves the creation of a side-to-side ileorectal pouch, or ileorectoplasty, that involves incorporating a 10-cm patch of ileum on its vascular pedicle into the anterior rectal wall to increase rectal capacity and compliance.189 In 11 subjects, at medium-term follow up (4.5 years), rectal capacity was increased, with an associated improvement in bowel symptoms (increased ability to defer defecation and reduced frequency of episodes of incontinence) and in patients’ quality of life.190

Other Procedures

Radiofrequency energy can be delivered deep to the mucosa of the anal canal via multiple needle electrodes with use of a specially designed probe (Secca System; Rayfield Technology, Houston) inserted into the anal canals of patients with fecal incontinence.191 The proposed mechanism of action is heat-induced tissue contraction and remodeling of the anal canal and distal rectum. In one study, symptomatic improvement was sustained at two and five years after treatment.192 A multicenter trial has confirmed the improvements in continence and quality of life, at least in the short term (at six months). Complications include ulceration of the mucosa and delayed bleeding.193 Interestingly, no changes were seen in the results of anorectal manometry, PNTML measurement, or anal endosonography. Results of a randomized controlled trial of this method completed in the United States are pending.

The Malone, or antegrade continent, enema procedure194 consists of fashioning a cecostomy button or appendicostomy195 to allow periodic antegrade washout of the colon. This approach may be suitable for children and for patients with neurologic disorders.195–197

If none of these techniques is suitable or all have failed, a colostomy remains a safe, although aesthetically less preferable, option for many patients.107,198–200 It is particularly suitable for patients with spinal cord injury, immobilized patients, and those with severe skin problems or other complications. A colostomy should not be regarded as a failure of medical or surgical treatment.171 For many patients with fecal incontinence, the restoration of a normal quality of life and amelioration of symptoms can be rewarding. The use of a laparoscopic-assisted approach, a trephine colostomy, may help to fashion a stoma with minimal morbidity for the patient.201 In one study, the total direct costs were estimated to be $31,733 for a dynamic graciloplasty, $71,576 for a colostomy including stoma care, and $12,180 for conventional treatment of fecal incontinence.202

Sacral Nerve Stimulation

Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) has emerged as a useful treatment option in selected patients, although how SNS improves fecal incontinence remains unclear.203 The benefit may relate to direct effects peripherally on colorectal sensory or motor function or to central effects at the level of the spinal cord or brain.204 Earlier studies were performed in subjects with a morphologically intact anal sphincter, but subsequent reports have described the treatment in patients with EAS defects,205 IAS defects,206 and cauda equina syndrome207 or spinal injuries.208

The technique of SNS consists of two phases. The first phase is a temporary trial phase of two weeks during which electrodes are implanted in the second or third sacral nerve roots and the nerves are stimulated with a neurostimulator device. If the patient reports satisfactory improvement of symptoms, a permanent neurostimulator device is placed in the second phase (Fig. 17-10). Initial reports of SNS have described marked improvements in clinical symptoms and quality of life and marginal effects on physiologic parameters.176,209 The results of multicenter studies of SNS have reported marked and sustained improvement in fecal incontinence and quality of life.210–212 A randomized controlled trial has found SNS to be superior to supportive therapy (pelvic floor exercises, bulking agents, and dietary manipulation),213 but long-term outcomes are not yet available. A morphologically intact anal sphincter may not be a prerequisite for success with SNS, and patients with EAS defects of less than 33% can be treated effectively with this method.214 A systematic review of the published outcomes of trials of SNS has revealed that 40% to 75% of patients achieve complete continence, and 75% to 100% experience improvement, with a low (10%) frequency of adverse events.215

An evidence-based summary of current therapies for fecal incontinence is shown in Table 17-6.

| TREATMENT | QUALITY OF EVIDENCE |

|---|---|

| Pharmacologic treatment | |

TREATMENT OF SUBGROUPS OF PATIENTS

Patients with Spinal Cord Injury

Patients with a spinal cord injury demonstrate delayed colonic motility or anorectal dysfunction that may manifest as incontinence, seepage, difficulty with defecation, or rectal hyposensitivity.216 Anal sphincter pressures and rectal compliance are low in these patients, but the correlation between manometric findings and bowel dysfunction is poor. Studies of translumbar and transsacral MEPs have shown profound neuromuscular dysfunction affecting the entire spinoanal and spinorectal pathways.109 Patients with a spinal cord injury may have fecal incontinence because of a supraspinal lesion or lesion of the cauda equina.77,78 In the former group, the sacral neuronal reflex arc is intact, and the cough reflex is preserved. Therefore, reflex defecation is possible through digital stimulation or with suppositories. In patients with a low spinal cord or cauda equina lesion, digital stimulation may not be effective because the defecation reflex is often impaired. In these cases, management consists of antidiarrheal agents to prevent continuous soiling with stool, followed by the periodic administration of enemas or the use of laxatives or lavage solutions at convenient intervals.2 A cecostomy procedure also may be appropriate.217 In some patients, colostomy may be the best option.198

Patients with Fecal Seepage

Because patients with fecal seepage show dyssynergic defecation with impaired rectal sensation, neuromuscular conditioning with biofeedback techniques to improve dyssynergia can be useful (see Chapter 18).58,218 Therapy that consists of sensory conditioning and rectoanal coordination of the pelvic floor muscles to evacuate stools more completely has been shown to reduce the number of fecal seepage events substantially and to improve bowel function and anorectal function by objective measures.58

Older Patients

Fecal incontinence is a common problem in older adults and may be a marker of declining health and increased mortality in patients in nursing homes.60 In one study, fecal incontinence developed in 20% of nursing home residents during a 10-month period after admission, and long-lasting incontinence was associated with reduced survival.116 In one report, immobility, dementia, and the use of restraints that precluded a patient from reaching the toilet in time were the most important risk factors for the development of fecal incontinence.219 Usual mechanisms of incontinence include impaired anorectal sensation, weak anal sphincter, and weak pelvic floor muscles. Decreased mobility and lowered sensory perception are common causes of incontinence.220 Many of these patients have fecal impaction and overflow.54,221 Fecal impaction, a leading cause of fecal incontinence in institutionalized older adults, results largely from a person’s inability to sense and respond to the presence of stool in the rectum. A retrospective screening of 245 permanently hospitalized geriatric patients222 has revealed that fecal impaction (55%) and laxatives (20%) are the most common causes of diarrhea and that immobility and fecal incontinence are strongly associated with fecal impaction and diarrhea. One study has shown that impaired anal sphincter function (a risk factor for fecal incontinence), decreased rectal sensation, and dyssynergia are seen in up to 75% of nursing home residents with fecal incontinence.36,223

Stool softeners, saline laxatives, and stimulant laxatives are frequently administered as prophylactic treatment to prevent constipation and impaction. In a study of institutionalized older patients, the use of a single osmotic agent with a rectal stimulant and weekly enemas to achieve complete rectal emptying reduced the frequency of fecal incontinence by 35% and the frequency of soiling by 42%.224 If fecal impaction is not relieved by laxatives and better toileting, a regimen of manual disimpaction, tap water enemas two or three times weekly, and rectal suppositories should be considered.225 In the presence of impaired sphincter function and decreased rectal sensation, however, liquid stools may be counterproductive. Similarly, neuromuscular training to improve dyssynergia in older adults, ritualizing the patient’s bowel habit, improving mobility, and cognitive training may be useful.60

Children

Incontinence is seen in 1% to 2% of otherwise healthy 7-year-old children.226 It is caused by functional fecal retention (previously described as encopresis), functional nonretentive fecal incontinence,227 congenital anomalies, developmental disability, or mental retardation.

In children with functional fecal retention, the bowel movements are irregular, often large, bulky, and painful. Consequently, when the child experiences an urge to defecate, he or she assumes an erect posture, holds the legs close together, and forcefully contracts the pelvic and gluteal muscles. Over time, this conscious suppression of defecation leads to excessive rectal accommodation, loss of rectal sensitivity, and loss of the normal urge to defecate. The retained stools become progressively more difficult to evacuate, thereby leading to a vicious cycle. The ultimate result is overflow incontinence, with seepage of mucus or liquid stool around an impacted fecal mass. This aberrant behavior may lead to the unconscious contraction of the external sphincter during defecation and cause dyssynergic defecation.221,228

By contrast, functional nonretentive fecal incontinence represents the repeated and inappropriate passage of stool at a place other than the toilet by a child older than four years with no evidence of fecal retention. According to criteria established by the Rome III consensus committee,227 children with functional nonretentive fecal incontinence often pass stools daily in the toilet but in addition have almost complete stool evacuations in their underwear more than once a week. They have no palpable abdominal or rectal fecal mass nor evidence of fecal retention on an abdominal x-ray, and colonic radiopaque marker studies are normal.229 The frequency of daytime and nighttime enuresis is higher (40% to 45%) in children with functional nonretentive fecal incontinence than in those with fecal retention. Children with functional nonretentive fecal incontinence have significantly more behavioral problems and more externalizing or internalizing of psychosocial problems than controls.