44 Facet Block

Placement

Anatomy

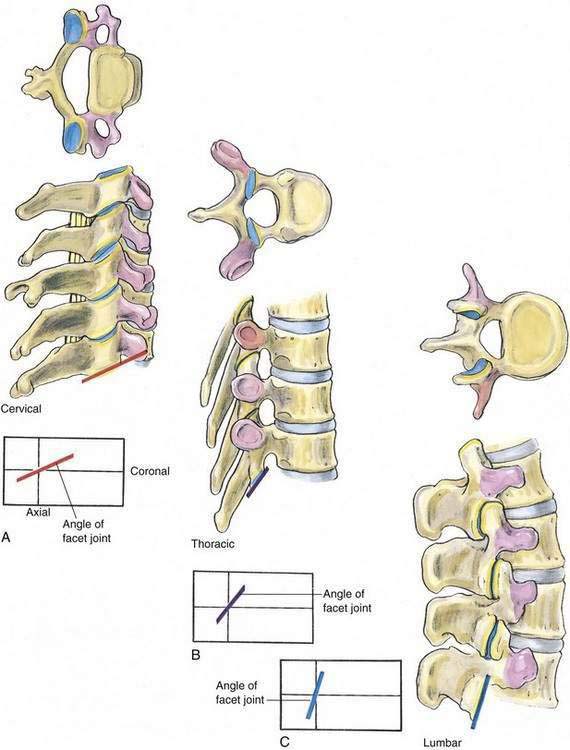

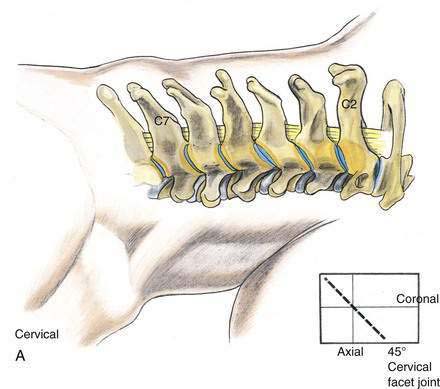

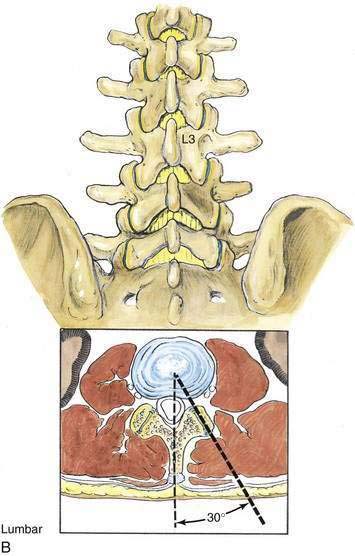

The 33 vertebrae that make up the spinal column are linked by intervertebral disks and longitudinal ligaments anteriorly and through facet joints posteriorly. The posterior facet joints allow flexion, extension, and rotation of the vertebral column while providing a means for the axial nerves to exit the vertebral column on their way to becoming peripheral nerves. The facet joints are synovial joints formed by the inferior articular processes of one vertebra and the superior articular processes of the adjacent caudad vertebra. These articular processes are projections, two superior and two inferior, from the junction of the pedicles and the laminae. In the cervical and lumbar portions of the vertebral column, the facet joints are posterior to the transverse processes, whereas in the thoracic region the facet joints are anterior to the transverse processes (Fig. 44-1). In the cervical vertebrae, the joint surfaces are midway between a coronal and an axial plane, whereas in the lumbar region, the joints (at least the posterior portion) assume an orientation approximately 30 degrees oblique to the sagittal plane (Fig. 44-2).

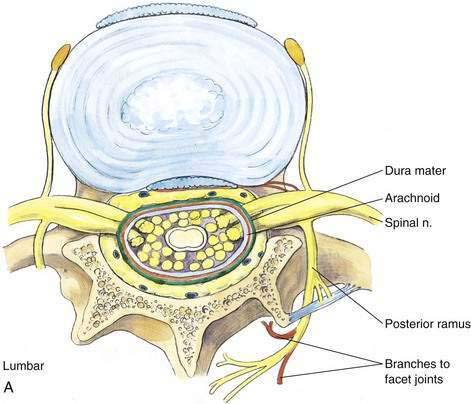

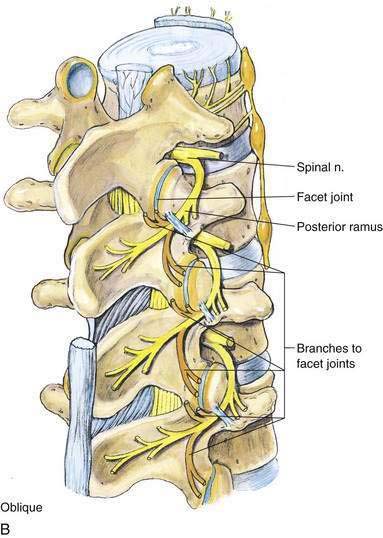

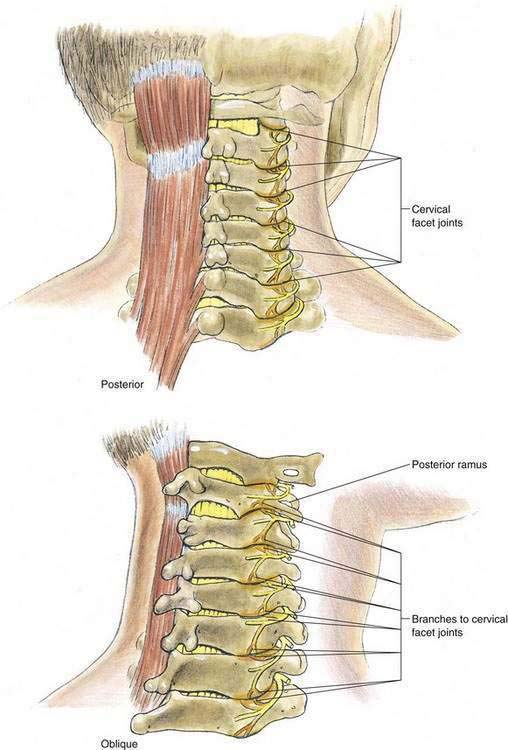

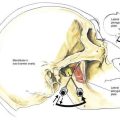

The facet joints are innervated through the segmental sensory nerves that overlap the vertebral levels. Each joint has a dual innervation from the segmental nerve at its vertebral level as well as from the nerve at the level caudad to it. In the lumbar region, the posterior and anterior primary rami of a segmental nerve diverge at the intervertebral foramen (Fig. 44-3A). The posterior ramus, also known as the sinuvertebral nerve of Luschka, passes dorsally and caudally to enter the spine through a foramen in the intertransverse ligament. Almost immediately it divides into medial, lateral, and intermediate branches. The medial branch supplies the lower pole of the facet joint at its own level and the upper pole of the facet joint caudad to it. Each medial branch of the lumbar posterior ramus also supplies paraspinous muscles, such as the multifidus and interspinalis, as well as ligaments and the periosteum of the neural arch (Fig. 44-3B). In the cervical region, the medial branch innervates primarily the facet joint and not the paraspinous musculature. Further, in the cervical region, the nerves of Luschka wrap around the waists of their respective articular pillars and are bound to the periosteum by an investing fascia and held against the articular pillars by tendons of the semispinalis capitis muscle (Fig. 44-4).

Position

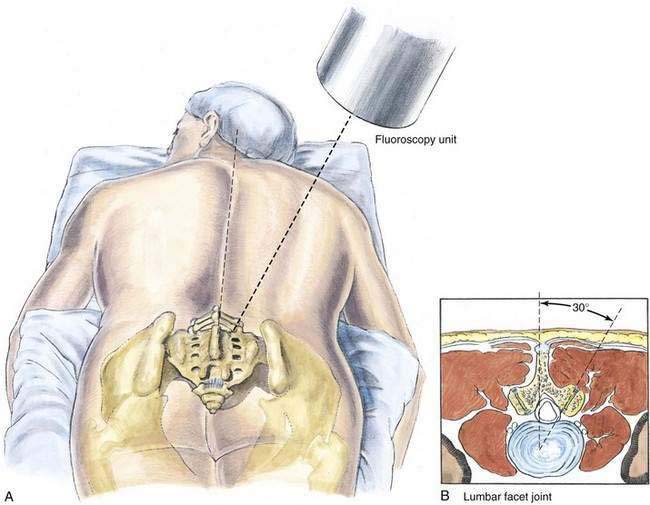

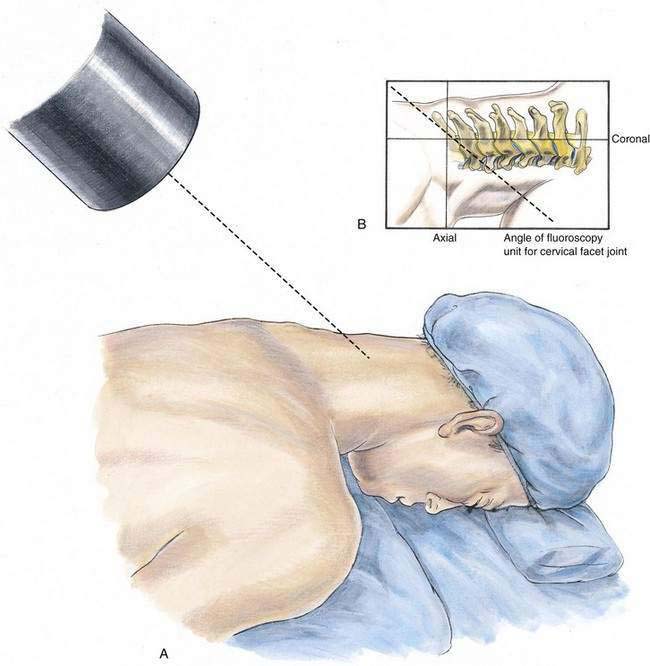

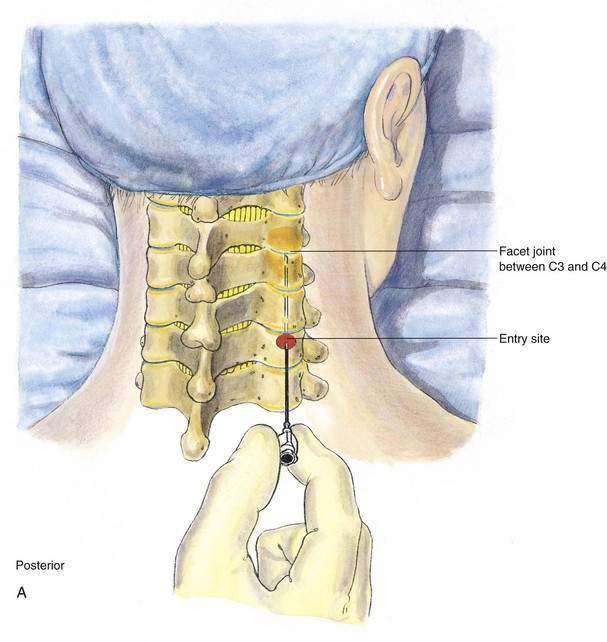

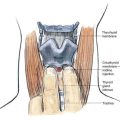

Lumbar facet blocks are performed with the patient prone on an imaging table with the hips and lower abdomen supported by a pillow. After the level of the facet joint is identified, the fluoroscopy unit is angled approximately 30 degrees off the parasagittal plane to obtain optimum visualization of the lumbar facet joint (Fig. 44-5). Cervical facet blocks are also performed with the patient prone on an imaging table with the forehead and chest supported by pillows or individual silicone pads (Fig. 44-6A). Again, fluoroscopy is used to identify the facet joint, and after its position has been marked, the fluoroscopy unit is rotated to produce a lateral image of the cervical spine.

Needle Puncture

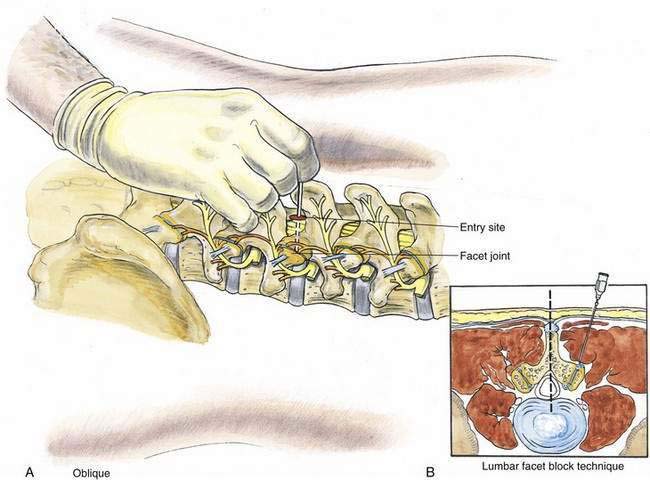

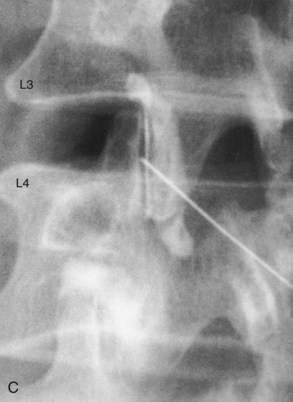

The facet joint is often located at the cephalocaudad level of the inferior extent of the more cephalad spinous process of the vertebra contributing to the facet joint. For example, the inferior extent of the spinous process of L3 corresponds to the L3-L4 facet joint. After the level of the facet joint has been marked, the fluoroscopy unit is angled approximately 30 degrees off the parasagittal plane, as described previously (see Fig. 44-5). A mark is then made 5 cm lateral to the vertebral midline at the previously identified facet joint level. After aseptic skin preparation, a 22-gauge, 6- to 10-cm needle is inserted at a slightly medial parasagittal angle. Under fluoroscopic guidance, the needle tip is placed in the facet joint (Fig. 44-7). Then a radiocontrast agent is injected to verify the position of the needle tip (see Fig. 44-6B). Once the needle position is confirmed, the therapeutic or diagnostic injection is performed.

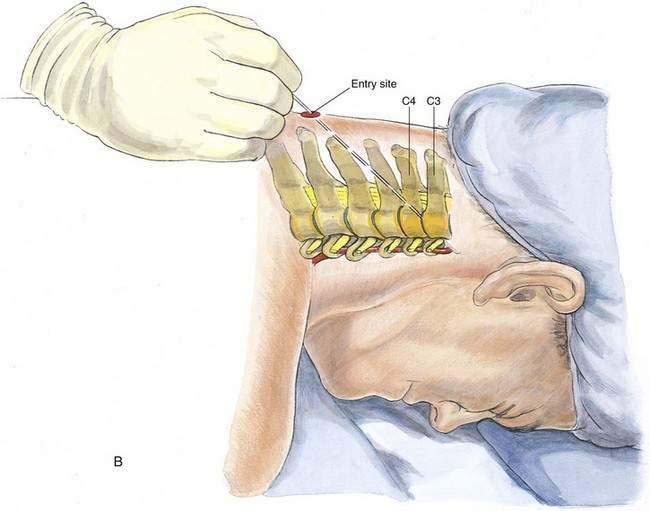

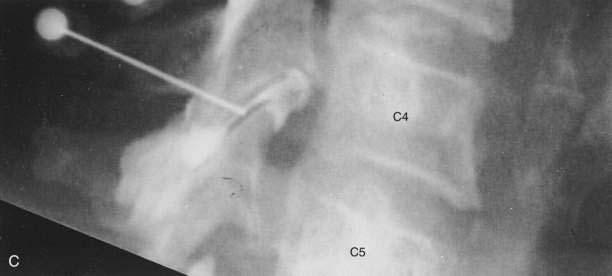

Cervical facet blocks are also performed with the patient prone on an imaging table, as described earlier. Fluoroscopy is used to identify the facet joint to be blocked, and its cephalocaudad vertebral level is marked. After the paravertebral cephalocaudad and mediolateral positions of the facet joint have been marked, the fluoroscopy unit is rotated to produce a lateral image of the cervical spine. This allows optimum visualization of the cervical facet joint during needle placement. A needle entry skin mark is made 3 to 4 cm caudad to the facet joint previously identified and approximately 3 cm lateral to the vertebral midline (Fig. 44-8A). After the skin has been aseptically prepared, a 22-gauge, 6- to 8-cm needle is inserted in a cephaloanterior direction and guided with fluoroscopic assistance into the previously identified cervical facet joint (Fig. 44-8B). Radiocontrast medium is then injected to verify the position of the needle tip (Fig. 44-8C). Once the needle position has been confirmed, the therapeutic or diagnostic injection is performed.