CHAPTER 7 Facelift with SMAS technique and FAME

History

Surgery of the deep layer tissues of the face and neck is now established as a permanent part of facelift operations. There is no clear consensus as to how to treat the midface and its related nasolabial fold. Skoog introduced tightening of the midface superficial fascia and platysma muscle in the late 1960s, and Mitz and Peyronie verified the anatomy of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) in 1976. Surgery of the midface developed subsequent to descriptions of the retaining ligaments of the cheek, as the focus of facial rejuvenation extended to correction of the nasolabial fold. Masseteric-cutaneous and lateral zygomatic-cutaneous ligament release allowed lifting of the SMAS to correct the lower face below the zygoma. However, approaches to the prezygomatic SMAS developed in an effort to gain harmony of the upper and lower parts of the face. In this effort two different approaches are in use:

Physical evaluation

• Evaluate the face in general for the bone structure of the entire face including the forehead, orbits, zygomas, zygomatic arches, maxilla, mandible, mentum, as well as the lips, nose and teeth.

• Evaluate skin quality and laxity, fat deposits and/or bulges in the face and neck.

• Evaluate midface thickness, laxity, and mobility to finger tip manipulation.

• Evaluate nasolabial folds, and labiomandibular folds if present.

• Evaluate neck including fat deposits, platysma muscle anatomy, hyoid position, thyroid cartilage contour and submandibular gland position.

• Evaluate the malar area for bony contour and the thickness of the soft tissue lying medial to the zygomaticus major muscle.

• Evaluate the lower eyelids for the integrity and function of the orbicularis oculi muscle.

• Evaluate the lower eyelids for prominence of herniated fat, prominence of the bony orbital rim, palpebromalar grove and nasojugal grove.

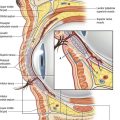

Anatomy

The midcheek can be understood as part of the midface and refers to a part of the cheek medial to a line extending from the frontal process of the zygoma to the oral commissure and from the lower lid above to the nasolabial fold below. It is composed of two functionally distinct parts including the prezygomatic part over the body of the zygoma and maxilla and infrazygomatic part below, as described by Mendelson (Ch. 6). A major determinant of the shape of the midface is the underlying skeleton as it connects the orbital and oral cavities and provides a bony platform for their skeletal attachments and retaining ligaments of each muscle. The aging changes that appear in the midcheek largely reflect the effect of laxity and ptosis of the soft tissues relative to the underlying skeleton. This affects the upper face by revealing the anatomy of the orbit, with exposure of the bony orbital rim inferiorly, palpebromalar groove laterally, and nasojugal groove medially. The displaced soft tissue accentuates the nasolabial fold and reveals lower lid fat bulges. With soft tissue descent, laxity of the structures of the prezygomatic space including the orbital retaining ligament at its uppermost aspect and its roof (pars orbitale of the orbicularis oculi) are resisted by the zygomatic-cutaneous ligaments below. When visibly enlarged this area forms the clinical entity known as the malar mounds, also termed malar bags and malar crescent. It should be noted that the presence of the malar septum was described by Pessa and Garza and Pessa et al. to explain the clinical appearance of a black eye, and explain the anatomic basis of malar mounds and malar edema. Malar mounds should be distinguished from the malar fat pad. The anatomical terminology regarding this area can be somewhat confusing, as the malar fat pad is also simply known as malar fat.

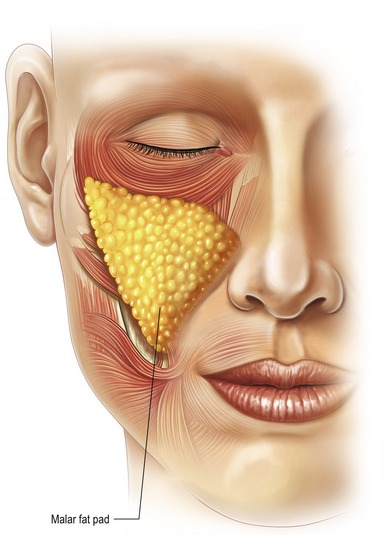

Specifically, the malar fat pad is a term used to describe the subcutaneous fat of the medial cheek that exaggerates the nasolabial fold. The malar fat pad is a localized thickness of the subcutaneous panniculus adiposus (Fig. 7.1). The malar fat pad is of maximum thickness centrally in youth with a well-defined border at the nasolabial crease and less discrete border in the upper face as it blends imperceptibly into the lower lid with a gradual decrease in thickness over the prominence of the orbital rim and zygoma. The malar fat has upper, middle and lower components. The fullness of the nasolabial fold is in large part caused by the medial and inferior migration of the soft tissue medial to the zygomaticus major muscle (primarily the malar fat pad). It is triangular in shape with its base along the nasolabial crease, and its apex overlies the body of the zygoma. The malar fat pad firmly attaches to skin. It is easily separated from underlying fascia, and the malar fat pad moves forward and down perpendicular to the nasolabial crease during the aging process.

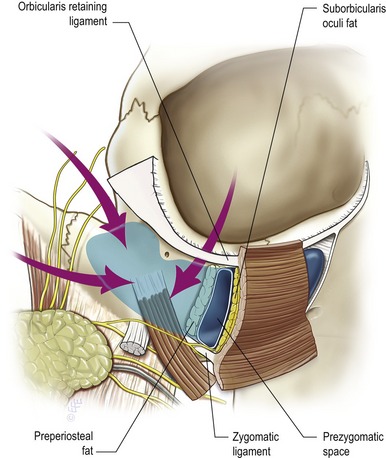

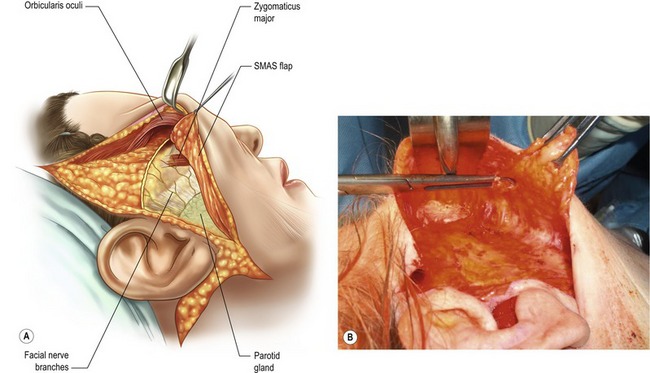

The prezygomatic space overlies the body of the zygoma and the origins of the lip elevator muscles. It extends to the posterior border of the body of the zygoma and can be accessed from the lower temporal region and lower lid. The floor is a thick layer of preperiosteal fat with an overlying thin membrane which covers the origins of the muscle bellies of the lip elevators. The upper border of the space is formed by the orbicularis retaining ligament, which separates the preseptal from the prezygomatic space and becomes confluent at the inferolateral orbital rim with the broad lateral orbital thickening that overlies the frontal process of the zygoma. The zygomatic-cutaneous neurovascular pedicle is the only structure crossing this space as Mendelson has previously elucidated. The roof of the space is the orbicularis oculi and its investing fascia, which is contiguous with the temporoparietal fascia laterally. The inferior wall of the prezygomatic space is lined by a continuation of the preperiosteal membrane and the most cephalad of the zygomatic-cutaneous ligaments as they extend between the origins of the lip elevator muscles through the subcutaneous fat to the dermis. With blunt dissection in this space, as in the FAME procedure, the smooth surface of this membrane remains intact and preperiosteal fat remains attached to the underlying facial bones. Mendelson has noted that the prezygomatic space can be entered from (1) the lower eyelid; (2) the temporal area; (3) laterally passing between the seventh nerve branches as performed with the FAME procedure to enter the prezygomatic space (Fig. 7.2).

Technical steps

The senior author (SJA) began using the FAME technique in the early 1990s as a procedure in conjunction with a standard SMAS/platysma facelift to improve the midface and nasolabial fold. The FAME technique (finger assisted malar elevation) is a composite technique designed to elevate skin, lateral orbicularis oculi muscle, and reposition the malar fat pad. This technique is used in combination with skin undermining and a SMAS/platysma flap to correct the remainder of the laxity in facial and cervical areas. The description given here is as performed for approximately 14 years. Recent modifications since February 2006 will be described below.

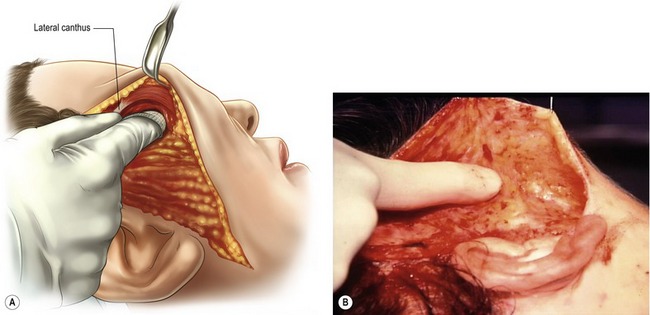

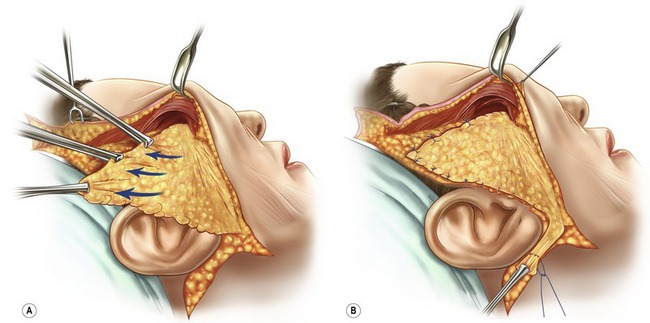

In the temporal area the skin is undermined sharply for approximately half the distance between the ear and lateral canthus. The right index finger is rotated medially and inferiorly so as to separate the orbicularis oculi muscle from the temporal fascia; the lateral canthus is easily reached (Fig. 7.3).

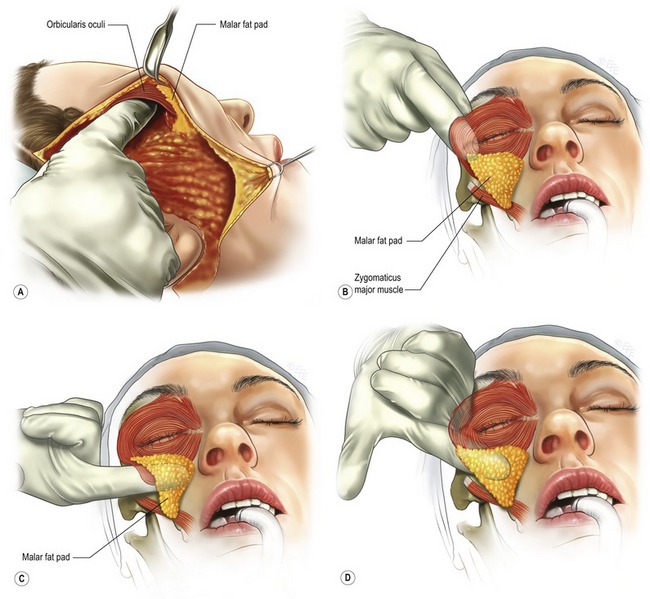

Attention is now returned to the lateral canthus. With the index finger pulp surface down under the orbicularis oculi muscle pressure is exerted downward, inferiorly, and medially across the malar prominence (Fig. 7.4A&B). The orbicularis oculi muscle and the malar fat pad separate rather easily from the underlying fascia overlying the preperiosteal fat thus entering the prezygomatic space (Fig. 7.4C). The entire malar fat pad in undermined with the index finger going to near the nasal alar attachment (Fig. 7.4D). The index finger is turned over with the pulp surface up in order to permit leverage for complete mobilization of the malar fat pad. Bimanual palpation with one index finger in the “deep plane” helps evaluate malar fat pad thickness and mobility (Fig. 7.5).

At this point the levels of dissection have been established (1) subcutaneously and (2) underneath the malar fat pad and orbicularis oculi (in the deep plane and a composite flap). The subcutaneous soft tissue bridge separates the two planes at the lower quarter of the malar prominence. Redraping of the composite flap in a cephaloposterior direction with the emphasis on the vertical vector will demonstrate repositioning of the malar fat pad to its earlier location over the malar prominence. If more mobility is needed for repositioning of the malar fat pad, the subcutaneous bridge is dissected until the desired mobility of the composite flap is achieved.

A SMAS flap is developed going inferiorly to join the subplatysmal dissection and going medially anterior to the parotid gland until the desired flap mobility is obtained. The SMAS platysma flap and, when indicated, anterior platysma procedures give independent control for lower facial and cervical contouring. The SMAS/platysma flap is elevated and rotated in the cephaloposterior direction with the vectors of lifting and repositioning according to the anatomy of the patient and the desired facial contouring.

The description of the technique above is as performed by the senior author for approximately 15 years. Most cases were performed without malar fat pad fixation to the zygoma. However, in some patients the malar fat was sutured to the periosteum of the zygoma to help maintain the vertical vector. In February 2006 the senior author modified the technique by extending the SMAS flap through the subcutaneous bridge between the deep plane and the subcutaneous plane. It is now an extended SMAS flap joining the FAME composite deep plane flap, thereby giving more mobility to the malar soft tissue (Fig. 7.6A&B). The SMAS flap is not excised but sutured to the temporal fascia (high lamella fixation) in order to maximize the vertical vector of the midface repositioning (Fig. 7.7A). The elevated malar fat pad is sutured to the periosteum of the zygoma in a vertical vector (Fig. 7.7B). In patients with a thin or poor quality SMAS, the FAME technique can be performed with plication of the SMAS. Likewise, a smasectomy can be performed with the FAME in patients where it is desirable to excise facial fat.

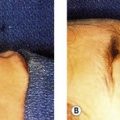

Redraping of the skin flap in the cephaloposterior direction repositions the malar fat pad and orbicularis oculi muscle. In general, the maximum vertical vector possible is desired in order to return the malar soft tissue onto the malar prominence. An incision is made beneath the temporal hairline so as not to narrow or elevate the sideburn. A Burrow’s triangle is excised so as to place only minimal tension on the elevated and rotated skin flap. Excess tension will only result in scar migration and add nothing to the lift. In the vast majority of patients, an incision along the anterior hairline is avoided entirely. When a small “dog ear” is present at the end of the transverse incision under the hairline, a small anterior hairline incision (5 to 7 mm) will eliminate the “dog ear” and permit restoration of the sideburn shape and position. The remainder of the skin flap is trimmed and sutured in a routine fashion. The FAME procedure can be performed with a short scar facelift technique or conventional scar technique, where the posterior scar is curved in the mastoid hair so as to be as almost imperceptible. Pre- and postoperative views of patients who have undergone a facelift with the FAME technique are shown (Figures 7.C1–C5).

Fig. 7.C1 A 58-year-old-patient following facialplasty with FAME technique, extended SMAS/platysma flap, endoscopic browlift and lower lid blepharoplasty. Postoperative photographs show lower and midface repositioning and lateral orbicularis tightening.

Fig. 7.C2 A 59-year-old patient 10 months postoperative facialplasty with FAME technique, extended SMAS, laternal platysma dissection, high lamella fixation, chin implant, 4-lid blepharoplasty, erbium laser resurfacing lower lids and rhinoplasty. Postoperative photographs show repositioning of mid and lower facial soft tissue and lateral orbicularis tightening.

Postoperative care

Sample instructions for the facelift patient

General

• Take pain medication as prescribed.

• Do not take aspirin, ibuprofen or any products containing these drugs, as they can cause bleeding problems after surgery. Tylenol is permissible. Also avoid vitamin E and multivitamins containing vitamin E. Stop herbal and homeopathic medications, as some may cause bleeding after surgery.

• Abstain from alcohol for a minimum of 7 days post-op. Do not drink alcohol when taking pain medications.

• Do not smoke, as smoking delays healing and increases the risk of complications.

• Following surgery, sleep on your back for 2 weeks. Keep head elevated on two pillows while sleeping.

• You may shampoo 24 hours after removal of the drainage tubes. Hair is generally shampooed on the 2nd postoperative day. Wash hair daily for two weeks following surgery. Use a cool setting on the hair dryer. Do not use rollers for 1 week after surgery. Do not color hair or use harsh chemicals prior to 2 weeks post-op.

• Soft foods are easier to consume post-op.

• Always use a strong sunblock, if sun exposure is unavoidable (SPF 30 or greater).

• You may use cold compresses for comfort and to help decrease the swelling.

Activities

• Start walking as soon as possible. This helps to reduce swelling and lowers the chance of blood clots in the legs.

• Do not drive until you are no longer taking any pain medications (narcotics), and can turn your neck easily.

• No strenuous activities, including sex and heavy housework, for at least 2 weeks. (Walking and mild stretching are permissible).

Incision care

• The area of sutures must be washed gently and thoroughly.

• Keep incisions clean and inspect daily for redness or signs of inflammation.

• You may use makeup after the sutures are removed; new facial makeup can be used to cover up bruising, but not on the incisions until 48 hours after suture removal. It is important to gently remove all makeup.

What to expect

• Swelling, bruising and numbness is normal and to be expected.

• Expect to feel tightness and a pulling sensation in your face and neck, especially when turning your head.

• Face may look and feel strange and distorted from the swelling.

• Men need to shave behind their ears, where beard-growing skin is repositioned.

• Expect a bruised and puffy face for 7–14 days, although some patients do not bruise at all. Wearing scarves, turtlenecks and high-collared blouses masks the swelling and discoloration.

• By the third week, you will look and feel much better.

• Final result is not fully realized for approximately 3 months.

Complications

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Apply firm downward fingertip pressure when dissecting across the temporal area to go under the orbicularis oculi muscle. This establishes the plane you want to be in.

• Inject anesthetic hemostatic agent perpendicular to the face of zygoma so as to infiltrate prezygomatic space.

• Apply fingertip pressure downward on malar bone to go under malar fat pad.

• Dissect prezygomatic space completely to mobilize entire malar fat pad.

• Use absorbable sutures (PDS, Vicryl, and Monacryl) to secure malar fat pad to periosteum.

Pitfalls

• Failure to dissect under the orbicularis oculi muscle laterally, therefore injuring the muscle and delaying the return of lower lid function.

• Failure to dissect under malar fat pad at its apex; therefore dissection will probably not be in the prezygomatic space but tear the malar fat pad.

• Injury to the small motor branch that crosses the upper zygomaticus major muscle to innervate the lateral orbicularis oculi muscle.

• Subcutaneous dissection medial to zygomaticus major muscle.

• Performing the procedure on a patient with thin malar fat pads.

Summary of steps

1. Infiltrate face and neck with anesthetic hemostatic solution.

2. Infiltrate prezygomatic space.

3. If indicated undermine anterior neck skin through a submental incision and perform anterior platysma procedure through submental incision.

4. Dissect sharply in the subcutaneous plane in the preauricular area and temporal area half distance to lateral canthus.

5. Rotate index finger downward and medially going under the lateral orbicularis oculi muscle.

6. Complete skin undermining as needed in cervical area.

7. Complete midcheek undermining in subcutaneous plane up to the lateral border of the zygomaticus major muscle.

8. Place index finger under lateral orbicularis oculi and push downward against malar bone so as to go under the apex of the malar fat pad.

9. Push index finger into the prezygomatic space and release the entire malar fat pad.

10. Bimanual palpation of malar fat pad to determine malar fat pad thickness.

11. Test mobility of this composite flap.

12. Perform lateral platysma and SMAS procedure (SMAS, extended SMAS, plication or smasectomy) as indicated for the individual patient.

13. Rotate and elevate the extended SMAS flap (most often used technique) and secure to temporalis fascia (high lamella fixation).

14. Redrape composite skin flap and determine position of the elevated malar fat pad with vertical vector.

15. Secure malar fat pat with 4-0 PDS to zygoma approximately 1 cm lateral to lateral canthus.

16. Redrape and trim skin flap, suture skin and place drains.

Aston SJ. The FAME technique, presented at the Aging Face Symposium. New York, NY: Waldorf Astoria Hotel; 1993.

Aston SJ. Platysma-SMAS cervicofacial rhytidoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1983;10(3):507.

Barton FE, Jr. The aging face: rhytidectomy and adjunctive procedures. Select Read Plast Surg. 2001;9(19):22.

Barton FE, Jr. Rhytidectomy and the nasolabial fold. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:601.

Hamra ST. The zygorbicular dissection in composite rhytidectomy: an ideal midface plane. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:1646.

Mendelson BC. Discussion; A study of long-term effect of malar fat repositioning in face lift surgery: short term success but long-term failure, by Sam T. Hamra, MD. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(3):952.

Mendelson BC. Surgical anatomy of the midcheek and malar mounds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(3):885.

Owsley JQ. Lifting the malar fat pad for correction of prominent nasolabial folds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91:463.

Skoog T. Rhytidectomy – A personal experience and technique, presented at the Seventh Annual Symposium of Cosmetic Surgery. Cedars of Lebanon Hospital, Miami, FL. 1973.

Stuzin JM, Baker TJ, Baker TM. Extended SMAS dissection as an approach to midface rejuvenation. Clin Plast Surg. 1995;22:295.