CHAPTER 5 Extremities

Nontrauma

SHOULDER PAIN

Calcium Hydroxyapatite Deposition Disease

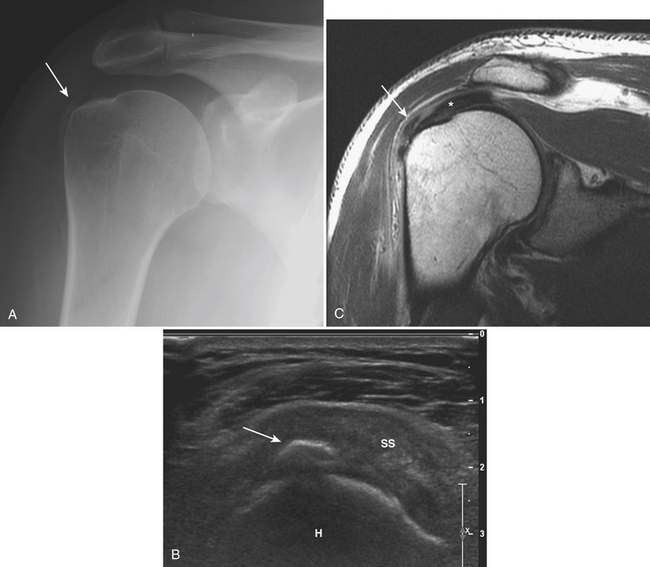

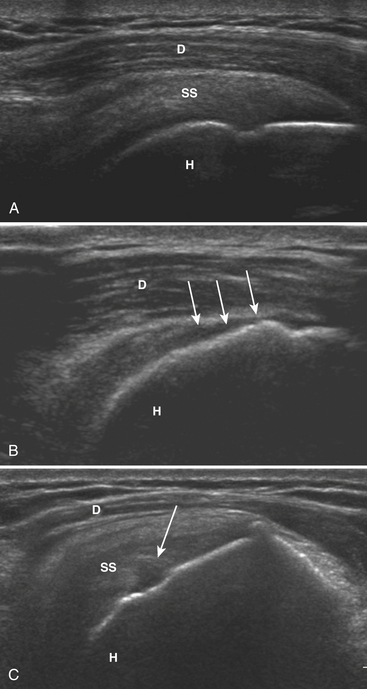

Calcific deposits are more easily identified and characterized with radiographs, computed tomography (CT), and ultrasonography (US) than with magnetic resonance (MR). On radiographs, most calcific deposits appear as homogeneous and amorphous densities, ovoid, linear, or triangular in shape, with and without internal trabeculations (Fig. 5-1A). The precise appearance and location varies with the phase of the disease process and specific anatomical structure involved. The supraspinatus is the most frequently affected tendon. US is highly sensitive for detecting even very small calcific deposits and may be used to guide puncture, aspiration, and lavage as therapeutic options. Hyperechoic foci with minimal or no significant posterior shadowing are identified, sometimes as ill defined and fluffy or as discrete, well-defined calcifications that are linear or rounded (Fig. 5-1B). Calcific deposits may be seen on MR as nodular foci of low signal intensity in all pulse sequences (Fig. 5-1C), and may be easier to identify on gradient-echo sequences, as they may induce blooming artifact. Inflammatory changes in surrounding soft tissues may be present and identified as heterogeneous hyperintensity in fluid-sensitive (T2-weighted and short T1 inversion recovery [STIR]) sequences.

Rotator Cuff Abnormalities and Impingement

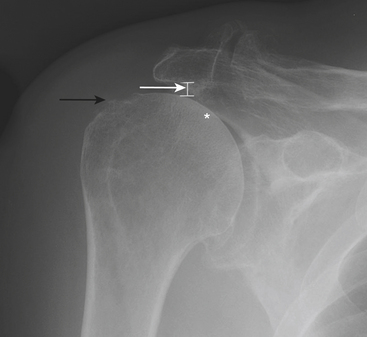

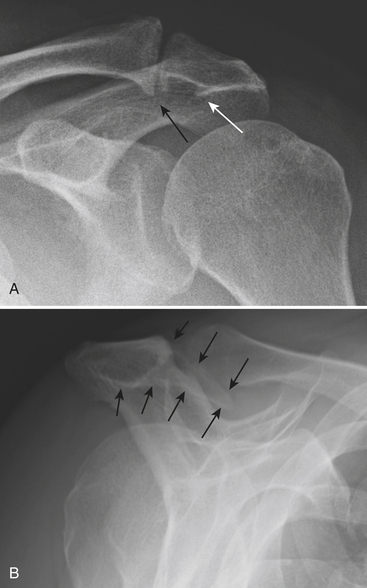

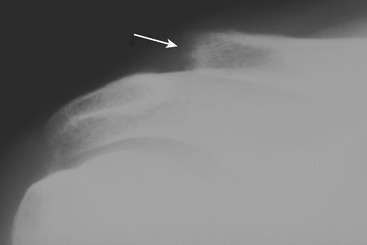

Radiographs should always be performed initially for evaluation of shoulder pain. However, they are often not contributory. The presence of gas from vacuum phenomenon in the glenohumeral joint strongly suggests the absence of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear. The rotator cuff tendons cannot be directly seen on radiographs; rather, there are a number of radiographic findings that serve as indirect evidence of cuff pathology and impingement (Fig. 5-2). These include superior subluxation of the humerus with a decreased subacromial space (less than 8 mm) and secondary changes in the humeral head, such as sclerosis, flattening, surface irregularity, and cystic changes. Radiographs may also demonstrate potential anatomic causes of impingement (Fig. 5-3).

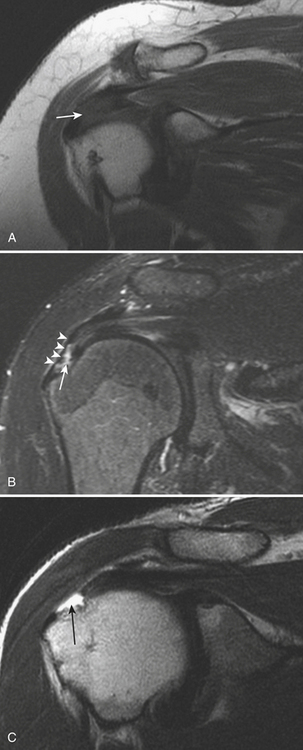

Rotator cuff tendinopathy (tendon degeneration) is characterized on MR by increased signal within the tendon on low TE sequences (T1 and proton density). The tendon may demonstrate associated focal or diffuse thickening, but this is not a constant finding (Fig. 5-4A). Abnormal signal within the rotator cuff tendons in low TE sequences may be seen in a variety of normal situations, and thus there is need for close clinical correlation: most commonly, magic angle artifact as an area of increased signal at 55 degrees from the main magnetic field, which, on oblique coronal planes, coincides with the supraspinatus “critical zone.” Cuff tendon tears present as disruption (interruption) of fibers and may be either partial or full-thickness in the craniocaudal plane. High-signal fluid is seen separating the disrupted fibers. This fluid may extend from the articular (inferior) surface superiorly in varying degrees to the bursal (superior) surface (Fig. 5-4B). Partial thickness tears affecting the articular surface are more common than isolated bursal surface tears. In full-thickness tears, fluid invariably extends across the tendon (Fig. 5-4C) into the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa. Subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis may occur in isolation or in conjunction with rotator cuff tears.

Figure 5-5A shows an intact supraspinatus and its relation to the humeral head and deltoid muscle. The primary or direct signs of full-thickness supraspinatus tear in US include nonvisualization of the tendon and a hypoechoic or anechoic full-thickness defect filling the gap of the torn tendon (Fig. 5-5B). Secondary or indirect signs that are helpful to correlate with the primary signs include sagging of the peribursal fat, cortical irregularity at the greater tuberosity, fluid in the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa, and muscle atrophy. Partial-thickness tears manifest sonographically as focal areas of hypoechoic or anechoic tendon defects involving the bursal or articular surface (Fig. 5-5C). An adequate exam requires evaluation of the extension of the defect on two orthogonal planes to confirm the findings. Tendon degeneration is demonstrated as internal heterogeneous echogenicity.

Acromioclavicular Joint Disease (Osteolysis and Osteoarthritis)

Osteolysis

When advanced, resorption of the distal clavicle may be easily recognized radiographically (Fig. 5-6), with loss of up to 3 cm of bone and widening of the acromioclavicular joint. The radiologist, however, should focus on identifying early signs, as immobilization seems to diminish the amount of bone loss and shorten the natural course of the lytic phase. Early radiographic signs include soft tissue swelling, demineralization, and loss of the subarticular sclerotic cortex at the distal end of the clavicle. MR findings usually precede radiographic findings. Initially, there is periarticular soft tissue swelling/edema, and a bone marrow edema pattern may be evident. The marrow signal abnormality can be limited to the distal end of the clavicle or involve the acromion as well, albeit to a lesser degree. There may be an associated joint effusion, although this finding is variable. The disease process then progresses to bone erosion and frank destruction. Other MR findings include cortical irregularity, subchondral erosion or cystic changes, and a subchondral line suggestive of a subchondral fracture.

Glenohumeral Joint Disease (Arthropathy and Adhesive Capsulitis)

Rheumatoid Arthritis

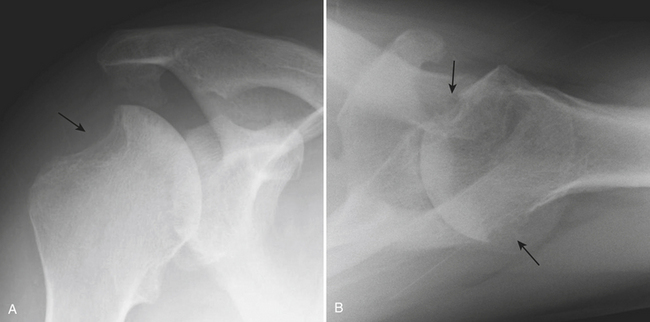

Conventional radiographs are still important for diagnosis and classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Classically, there is uniform joint space narrowing, periarticular demineralization, subchondral cystic changes, and marginal erosions. Erosions in the shoulder have a predilection for the lateral portion of the humeral head and may resemble a Hill-Sachs deformity (Fig. 5-7). Characteristically, there is lack of productive bone changes. Superior subluxation of the humeral head can also be seen, as chronic rotator cuff tear or cuff atrophy occurs frequently in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The role of other imaging tests for rheumatoid arthritis is still evolving. US and MR are more sensitive for detection of erosions and soft tissue findings. There may be a role for these modalities in early detection and for evaluation of disease activity or response to therapy. MR can demonstrate erosions earlier than plain radiographs, as well as subchondral cystic changes on both sides of the joint. Erosions are commonly located in the humeral head near the insertion of the rotator cuff tendons. MR can also show common findings not identifiable in radiographs, like joint effusion, signs of synovitis, tears or atrophy of the rotator cuff muscles and tendons, synovial cysts, bursitis, and rice bodies. Routine MR is limited for evaluation of glenohumeral articular cartilage.

THE PAINFUL HIP

Insufficiency Fractures

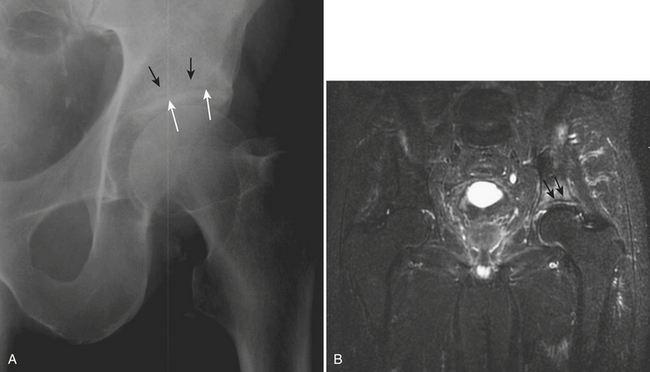

Insufficiency fractures are a type of stress fracture that occurs when a usual strength or physiologic force is applied to an abnormal or weakened bone. Most insufficiency fractures are caused by osteoporosis. In the pelvis, subcapital neck fractures (Fig. 5-8) are by far the most common. However, these fractures are usually associated with some degree of trauma. Common locations in the pelvis not usually associated with trauma include the sacrum, pubic rami, and supra-acetabular region. Undisplaced insufficiency fractures are very difficult to diagnose on conventional radiographs. Good radiographic technique and a high index of suspicion, especially when evaluating demineralized bones, are essential. If a stress fracture is suspected clinically and radiographs are not diagnostic, an MR examination should be obtained if available. MR is more accurate than scintigraphy. Additionally, MR may demonstrate coexisting conditions or alternative diagnoses that may influence management.

Radiographic findings may be occult or very difficult to detect and depend on the site of the fracture. Most commonly, a sclerotic band or line is evident. This finding is usually subtle and most often the only indication of a stress fracture. Evaluation for symmetry on the anteroposterior view of the pelvis is essential. Other potential findings include a fracture line, cortical disruption, and periosteal reaction. Supra-acetabular insufficiency fractures should be considered in elderly females with hip pain and no history of trauma. Particular attention should be paid to the distinct trabecular pattern of the acetabulum. Dense trabeculae outline a more lucent triangular area immediately above the sclerotic acetabular roof. A band of sclerosis within this triangular lucent region, parallel to the roof of the acetabulum, is characteristic and should be diagnostic of a stress fracture in most cases (Fig. 5-9).

MR is a highly sensitive and accurate tool for the diagnosis of insufficiency fractures. T1-weighted images may identify the fracture line itself as a serpiginous line of low signal intensity. On T2-weighted images with fat saturation and STIR sequences, the fracture line (high or low signal) may be obscured by the surrounding marrow edema in the acute setting. Linear low-signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences located in the supra-acetabular region running parallel to the acetabular roof is the characteristic finding of an insufficiency fracture (see Fig. 5-9).

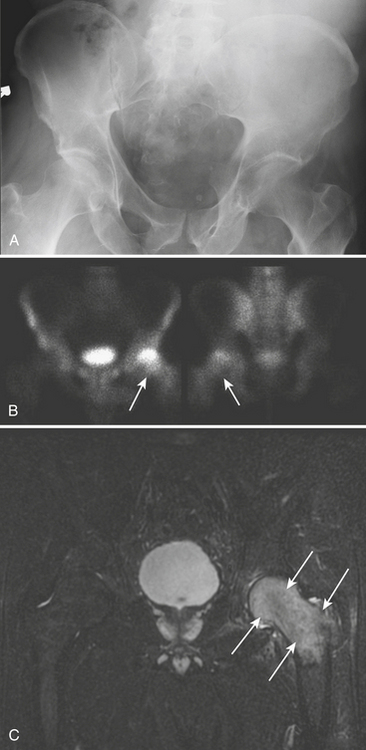

Transient Bone Marrow Edema and Transient Osteoporosis of the Hip

Conventional radiographs are normal initially and, over time, show variable degrees of demineralization involving the femoral head and neck regions (Fig. 5-10A). The acetabulum may occasionally be involved, but to a lesser degree. The joint space is preserved. Loss of the subchondral cortex of the femoral head is characteristic. Bone scintigraphy is abnormal before radiography. Increased, often extensive and homogeneous, uptake is evident in the femoral head and neck (Fig. 5-10B). MR shows a bone marrow edema pattern in the head and neck of the femur, sometimes extending into the intertrochanteric region (Fig. 5-10C). Mild involvement of the acetabulum is an inconsistent finding. Heterogeneous low-signal intensity on T1 and high-signal intensity on fluid-sensitive sequences are noted. A joint effusion is frequently present. The surrounding soft tissue and the contralateral side are normal.

Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head

Even though there is no universally satisfactory therapy for early stage disease, diagnosis of this entity before the joint is affected leads to an improved long-term prognosis. The Ficat classification, described in the 1980s, describes five stages based on clinical and radiographic findings (Table 5-1). Additional classification systems incorporating MR findings have also been developed. Imaging plays a pivotal role for the diagnosis, the determination of prognosis, and planning appropriate treatment. The size of the osteonecrosis lesion is an essential parameter for determining prognosis. The presence of bone collapse and joint involvement influences potential treatment options.

| Stage | Pain | Radiography |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | – | Normal |

| I | + | Normal |

| II | + | Cysts and/or sclerosis |

| III | ++ | Collapse (“crescent” sign, step-off in contour, flattening of articular surface) |

| IV | +++ | Osteoarthrosis (joint space narrowing, acetabular disease) |

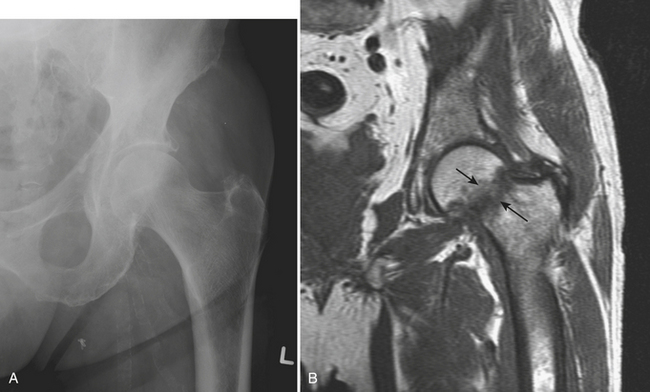

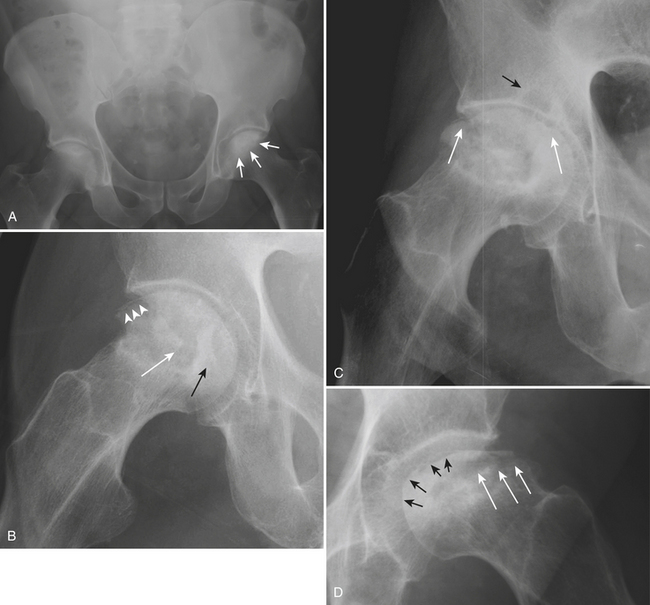

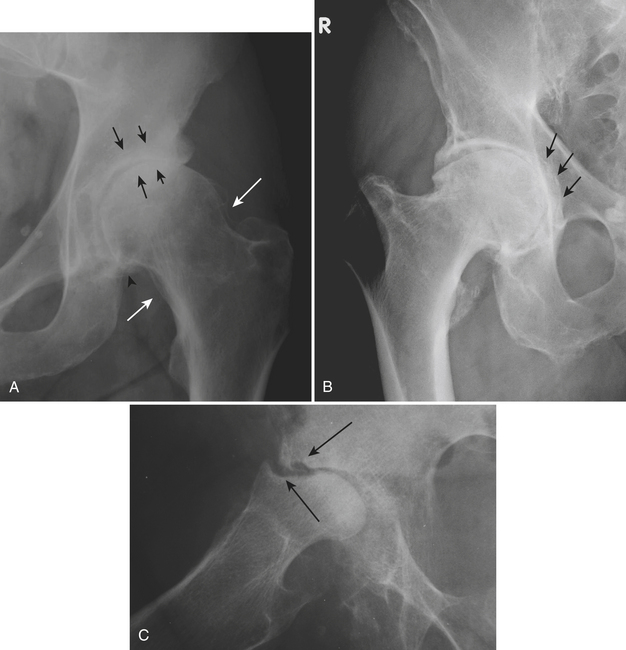

Initially, conventional radiographs are normal. In the reparative phase, both lytic and sclerotic areas are identified in the femoral head (Fig. 5-11A). Next, a subchondral fracture may develop. This manifests itself on radiographs as a subchondral crescent lucency (“crescent” sign) and is best seen on the frog leg lateral view (Fig. 5-11B). As the disease progresses, subarticular collapse may follow; this is seen as a loss of the normal rounded contour and flattening of the femoral head (Fig. 5-11D). Ultimately, severe collapse and destruction of the femoral head will lead to secondary osteoarthritis with joint space narrowing, osteophytes, subchondral cyst formation, and involvement of the acetabulum (Fig. 5-11C).

MR is more sensitive and specific than radiography and scintigraphy (Fig. 5-12). MR provides an accurate estimation of the size of the lesion and demonstrates early subarticular collapse and secondary osteoarthritis. It is essential that the MR examination include both hip joints, as osteonecrosis is bilateral in more than 50% of cases. The superoanteromedial quadrant of the femoral head is most frequently involved. A focal abnormality is seen outlined by a low-signal intensity margin. This margin represents the reactive interface between necrotic and viable bone and extends to the subchondral bone. The characteristic “double line” sign is seen on T2-weighted images and consists of an inner rim or band of high-signal intensity outlined by an outer low-signal margin. A subchondral fracture appears as a high-signal subchondral crescent on fluid-sensitive sequences. Identification of subchondral collapse, when present, is crucial. Flattening of the articular surface is often seen earlier on the sagittal plane. The MR appearance of late osteonecrosis with severe joint destruction is confusing and may be misinterpreted as neuropathic arthropathy or septic joint. Prior history and prior imaging are of utmost importance for making the differential diagnosis.

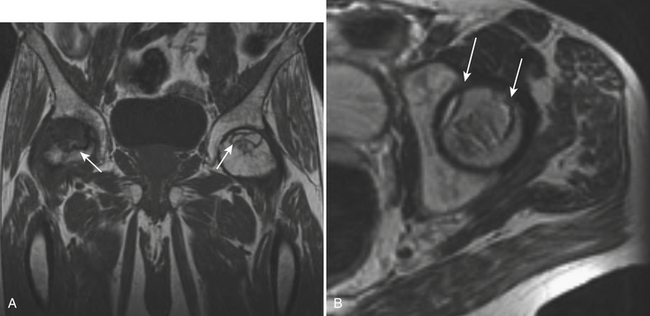

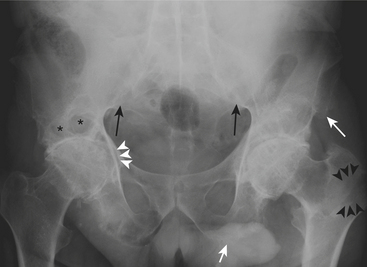

Arthropathies

Osteoarthritis is by far the most common arthropathy affecting the hip. Nonuniform joint space narrowing occurs most commonly superiorly, with the femoral head migrating superomedially or, more commonly, superolaterally. Buttressing (thickening of bone) of the femoral neck is a characteristic but not pathognomonic finding. The classic findings of osteoarthritis, namely, marginal osteophytes, subchondral cyst formation, and eburnation, can also be found in the hip (Fig. 5-13A). Occasionally, acetabular protrusio can be a result of osteoarthritis. In this condition, medial (rather than superior) migration of the femoral head occurs (Fig. 5-13B). Other causes of protrusio include Paget’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, osteomalacia, trauma, ankylosing spondylitis, radiation, and infection. A particularly destructive but rare form of osteoarthritis can be seen with a rapid progression of disease, mainly in the elderly. Awareness of rapidly destructive osteoarthritis is important to avoid misdiagnosis as a more aggressive or infectious arthropathy (Fig. 5-13C). In osteoarthritis, MR directly demonstrates loss of articular cartilage earlier and may also identify synovial cysts. MR is particularly useful in the differential diagnosis of osteoarthritis in cases with a confusing clinical presentation and nonspecific radiographic findings.

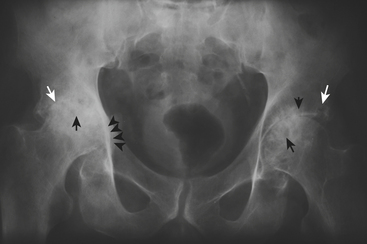

Rheumatoid arthritis can affect the hip joint and causes uniform joint space narrowing. Characteristic radiographic findings include bilateral and symmetric periarticular demineralization, erosions, and lack of proliferative changes (Fig. 5-14). Acetabular protrusion if bilateral and symmetric, should favor the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Additional findings seen on MR examinations include joint effusion, trochanteric or iliopsoas bursitis, tendon ruptures, pannus, and rice bodies.

The seronegative spondyloarthropathies commonly affect the hip joint. These are a group of joint conditions that include ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis (e.g., Reiter’s syndrome), psoriatic arthritis, arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease, and undifferentiated spondyloarthropathies. The joint space appears uniformly narrowed with productive bone changes. Bone mineralization is relatively preserved. Enthesophytes (proliferative bone changes that occur at the insertions of ligaments and tendons) occur commonly. Late-stage complications include acetabular protrusion and ankylosis. Careful attention must be paid to the sacroiliac joints, which often reveal bilateral symmetric involvement in ankylosing spondylitis (Fig. 5-15) and unilateral or bilateral asymmetric involvement in the other spondyloarthropathies.

APPENDICULAR MUSCULOSKELETAL INFECTION

Soft Tissue Infection

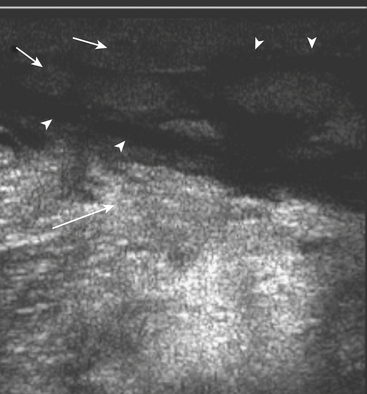

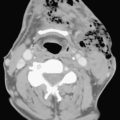

Cellulitis, an acute suppurative infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissues, is usually the result of contiguous spread of infection from skin breakdown, and is the initial step in the development of deep soft tissue infections. Findings on radiographs are minimal and nonspecific: increased soft tissue density, soft tissue swelling, and infiltration of the subcutaneous fat. Small radiolucent foci may be seen if gas is present (Fig. 5-16). CT may demonstrate thickening of the skin, subcutaneous tissues, and fascia (Fig. 5-17). US demonstrates increased echogenicity of the involved tissues and anechoic bands traversing the subcutaneous tissues, giving them a cobblestone appearance (Fig. 5-18). Findings on MR are similar, with decreased T1 signal and increased T2 signal in the thickened and infiltrated skin, subcutaneous tissues, and fascia (Fig. 5-19). Enhancement is variable. In clinically confusing cases, the finding of intense enhancement favors the diagnosis of cellulitis over noninfectious causes of subcutaneous edema that otherwise could have the same imaging findings. Three-phase bone scintigraphy demonstrates increased blood flow (initial phase) and blood pool (early phase) activity. Delayed images (third phase) are normal or demonstrate only mild increased uptake of the involved soft tissues.

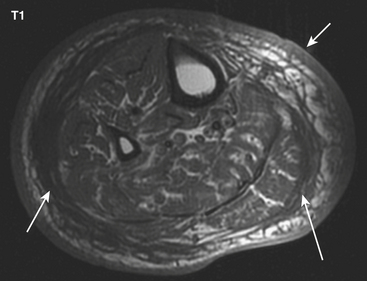

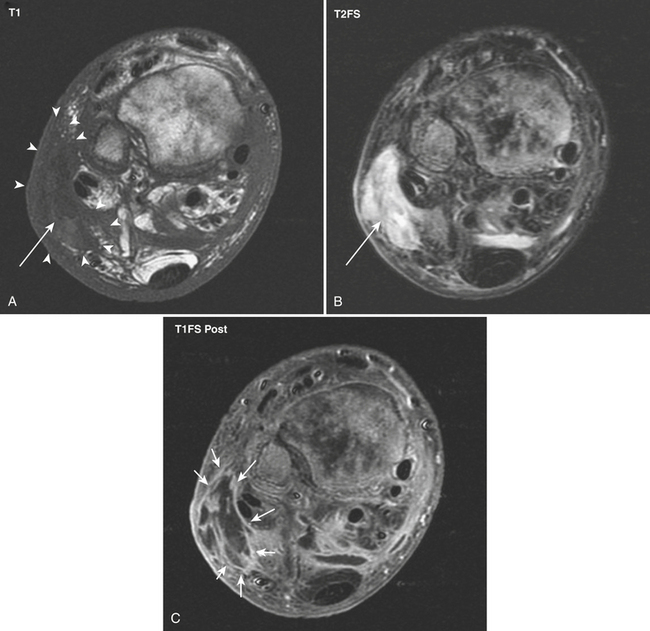

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare but very aggressive and often fatal condition characterized by necrosis of subcutaneous and deep fascial tissues. Patients with underlying conditions leading to decreased immunity, such as the elderly, those with HIV infection and leukemia, drug abusers, alcoholics, and those taking immunosuppressive medication, are all at increased risk of developing this lethal disease. The infection is most commonly polymicrobial, with both aerobic and anaerobic organisms. The disease is a surgical emergency requiring fasciotomy and extensive débridement of the necrotic tissue. Rapid diagnosis and prompt surgical intervention are essential. Cellulitis has clinical and imaging characteristics similar to those of necrotizing fasciitis, but the treatment is not surgical. The clinical dilemma always lies between acting rapidly and waiting for imaging test results that may or may not be helpful. If imaging cannot be done expeditiously, delaying surgical intervention is not justified. Radiographic and sonographic findings are similar to those of cellulitis, but with more severe involvement (Fig. 5-20). Presence of soft tissue gas on radiographs is an ominous sign. Severe asymmetric thickening, with air and fluid collections, is the hallmark of necrotizing fasciitis on CT. However, this constellation of findings occurs inconsistently. CT often demonstrates nonspecific thickening and enhancement of the superficial and deep fascial layers. MR images show thickening, high T2 signal, and abnormal enhancement in the subcutaneous tissues and deep fascial planes. However, when necrosis is established, only minimal or peripheral enhancement surrounding the area of necrosis may be present. MR overestimates the extent of deep fascial involvement as compared with findings at the time of surgery. The absence of deep fascial involvement on MR virtually excludes the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis.

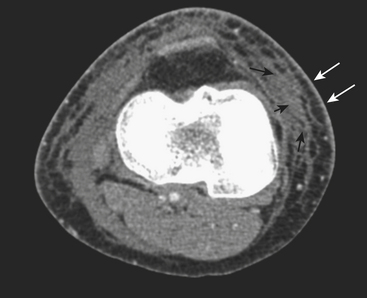

An abscess is defined as a localized collection of pus (necrotic tissue, inflammatory debris, and bacteria). An earlier stage in the development of an abscess, before liquefaction and organization ensue, is called a phlegmon. An abscess can occur anywhere in the soft tissues and, when located in a skeletal muscle (which is relatively resistant to infection), the term pyomyositis is used. Radiographs may be noncontributory, showing only diffuse or focal increased soft tissue density, focal prominence of the affected soft tissues, and displacement of fat pads. The sonographic appearance of abscesses is variable. Most commonly, a complex hypoechoic, predominantly fluid-containing mass with increased through-transmission is identified. The margins of the mass may be well or ill defined, depending on the stage of evolution. Internal septations and amorphous internal echoes are additional common findings (Fig. 5-21). Often, dynamic evaluation of the area with gentle compression is necessary to reveal the liquid nature of the contents. Color or power Doppler demonstrates absent internal flow and hyperemia of the wall and adjacent tissues. CT reveals an organized low attenuation fluid collection with an enhancing wall of variable thickness (Fig. 5-22), internal septations, and high-attenuation internal foci. Surrounding edema or findings of cellulitis are common. MR depicts abscesses and adjacent soft tissue changes to greater advantage (Fig. 5-23). Focal fluid collections demonstrating low or intermediate signal on T1- and high signal on T2-weighted sequences surrounded by reticulated, edematous soft tissue are characteristic. Intravenous contrast increases the conspicuity of the lesion with intense peripheral (wall) enhancement.

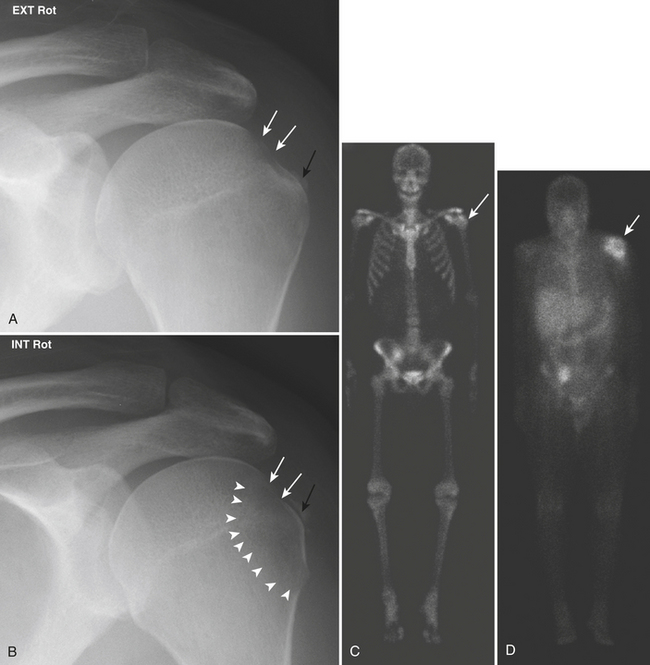

Infectious Arthritis

Early findings on conventional radiographs include periarticular demineralization, joint widening/effusion, and soft tissue swelling. Later, there may be joint space narrowing, periosteal reaction, erosions (both marginal and central), destruction of the subchondral bone, subluxations and dislocations, and, ultimately, ankylosis (Figs. 5-24 and 5-25). Intra-articular gas is a rare finding. The diagnosis of septic joint superimposed on known rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory arthropathy is very challenging. Infection should be suspected if there is widening of the joint space along with rapid articular destruction and significant soft tissue asymmetry.

Sonography is very sensitive for demonstrating a joint effusion and an excellent tool for aspiration guidance. Synovial thickening is seen consistently in infectious and inflammatory arthropathies. Bone scintigraphy demonstrates increased blood flow, prominent blood pool, and increased delayed activity in the distribution of the affected joint. The use of gallium citrate as a marker of inflammation has been greatly replaced by imaging with labeled leukocytes, either with indium 111 or technetium 99m hexamethylpropylene-amine-oxime. Increased tracer uptake of these agents in the joint improves specificity for the diagnosis of infectious arthritis (see Fig. 5-24).

CT is rarely used for imaging patients with suspected joint infection, except for patients with orthopedic hardware. All findings described in conventional radiographs may be seen on CT, easier and earlier (see Fig. 5-24). Additionally, synovial thickening may be identified. Synovial and periartcular soft tissue enhancement is variable.

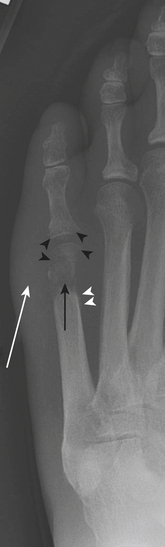

Acute Osteomyelitis

The overall sensitivity of conventional radiographs for early osteomyelitis is poor. Appearance of radiographic findings may be delayed for weeks after the initial infection. The earliest sign is usually swelling of the deep soft tissues. Early radiographic findings in the bone itself include focal demineralization and periosteal reaction. However, periosteal reaction may be absent in small bones such as those of the feet. Later, cortical lucency and frank bone destruction occur (see Fig. 5-25). Sonography is limited for the diagnosis of acute osteomyelitis. Deep soft tissue swelling, adjacent to the bone, may be seen, but this finding is nonspecific. A fluid collection immediately adjacent to the bone in the proper clinical setting is highly suggestive of osteomyelitis, but is rarely observed. CT is helpful in selected cases of acute osteomyelitis, although osseous findings may be detected to greater advantage and earlier than in radiographs. These include focal demineralization of the affected bone, cortical destruction, periosteal reaction, and hyperattenuation of the bone marrow. Soft tissue findings associated with osteomyelitis can also be demonstrated.

Soft tissue findings are almost invariably seen in patients with osteomyelitis. Soft tissue findings include ulcers, sinus tracts, cellulitis, and abscess formation (Fig. 5-26). The MR features of most of these conditions have already been described in this chapter. An ulcer presents on MR as a cutaneous and soft tissue defect with granulation tissue at its base, which usually enhances avidly after administration of gadolinium chelates. Sinus tracts may extend outward from the bone to the superficial soft tissues and skin or inward from an ulcer toward the bone. Sinus tracts appear as linear areas of increased signal on fluid-sensitive sequences, but they are much more easily identified after contrast administration as parallel linear areas of enhancement in a “tram–track” pattern.

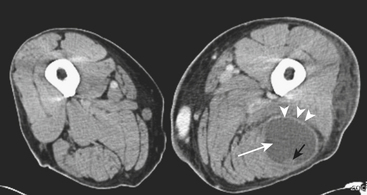

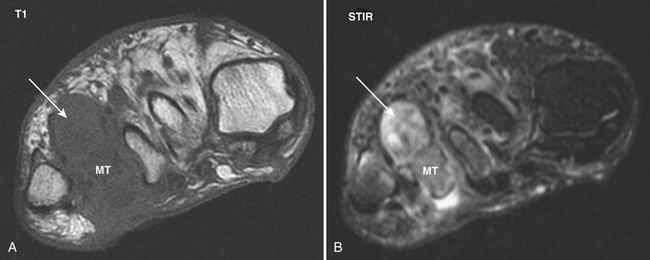

Foreign Bodies

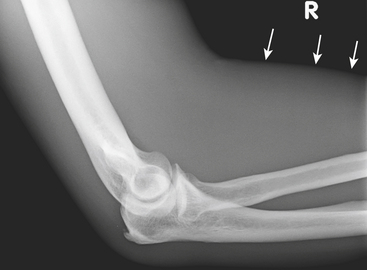

Puncture wounds and suspected retained foreign bodies (FBs) are a common cause of emergency room visits. Retained FBs are frequently overlooked initially, leading to inflammatory and infectious complications that are often severe. Therefore, prompt detection and removal are imperative. Precise localization of the object is extremely useful as this may minimize the extent of surgical dissection and shorten surgical time. A high clinical suspicion is always necessary, especially in patients with neuropathy who may be unaware of a prior puncture and present with a soft tissue infection (Fig. 5-27A and B). Wood, glass, and metal account for the vast majority of retained FBs encountered. On conventional radiographs, metal is almost always visible. Glass is seen radiographically in more than 90% of cases. On the other hand, wood is identified in only a minority of patients (approximately 15% or less).

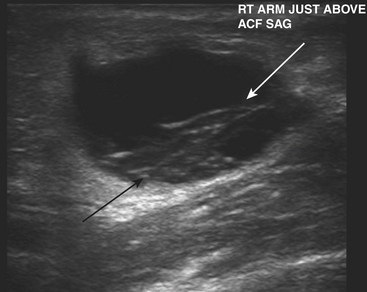

Ultrasound is highly sensitive and specific in the detection of retained FBs. US is rapid, inexpensive, accessible, and lacks ionizing radiation. It should be the modality of choice for radiographically occult FBs in the superficial soft tissues. All FBs are hyperechoic with acoustic posterior shadowing (see Fig. 5-27C). The degree of acoustic shadowing is variable and depends on the surface characteristics rather than the composition of the FB. Flat, smooth surfaces often encountered in metal and glass produce reverberation artifact or “dirty” shadowing, whereas irregular surfaces usually produce “clean” shadowing. Sonographic detection may be enhanced by the presence of a hypoechoic rim surrounding the FB. This rim may be seen after at least 24 hours, when an inflammatory reaction has developed. US also allows examination of the surrounding tissues for infectious complications and associated soft tissue injuries.

MR is rarely used in the acute setting for the detection of foreign bodies. More commonly, FBs may be detected incidentally on MR scans performed for the work-up of musculoskeletal infection. Foreign bodies exhibit low signal intensity on all pulse sequences and may show magnetic susceptibility artifact. Conspicuity on MR depends on size, location, and composition. Small FBs are difficult to distinguish from adjacent low-signal structures such as tendons, scars, and calcifications. Foreign objects may incite an inflammatory reaction, seen as surrounding areas of low signal intensity on T1- and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. MR is highly accurate for identifying infectious musculoskeletal complications (see Fig. 5-27D). Not infrequently, small FBs may become chronically embedded within the soft tissues and form foreign body granulomas. These lesions generate variable degrees of inflammatory response but often present with little or no T2 signal changes. They should be suspected when there is an area of magnetic susceptibility or signal void with peripheral enhancement.

Berquist T.H. Imaging of joint replacement procedures. Radiol Clin North Am. 2006;44:419-439.

Brower A.C., Kransdorf M. Imaging of hip disorders. Radiol Clin North Am. 1990;28:955-974.

Fang C., Teh J. Imaging of the hip. Imaging. 2003;15:205-216.

Hayes C.W., Conway W.F. Calcium hydroxyapatite deposition disease. Radiographics. 1990;10:1031-1048.

Mitchell M., Howard B., Haller J., et al. Septic arthritis. Radiol Clin North Am. 1988;26:1295-1313.

Morrison W.B. Ledermann HP: Work-up of the diabetic foot. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:1171-1192.

Rogers L.F., Hendrix R.W. The painful shoulder. Radiol Clin North Am. 1988;26:1359-1371.

Stiles R.G., Otte M.T. Imaging of the shoulder. Radiology. 1993;188:603-613.