Chapter 631 External Otitis (Otitis Externa)

Treatment

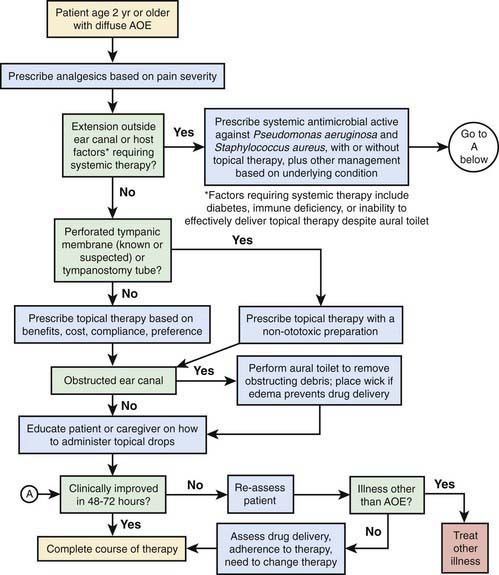

Topical otic preparations containing neomycin (active against gram-positive organisms and some gram-negative organisms, notably Proteus spp.) with either colistin or polymyxin (active against gram-negative bacilli, notably Pseudomonas spp.) and corticosteroids are highly effective in treating most forms of acute external otitis. Newer preparations of eardrops (e.g., ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin) are preferable and do not contain potentially ototoxic antibiotics. If canal edema is marked, the patient may need referral to a specialist for cleaning and possible wick placement. An otic antibiotic and corticosteroid eardrop is often recommended. A wick can be inserted into the ear canal and topical antibiotics applied to the wick 3 times a day for 24-48 hr. The wick can be removed after 2-3 days, at which time the edema of the ear canal usually is markedly improved, and the ear canal and TM are better seen. Topical antibiotics are then continued by direct instillation. When the pain is severe, oral analgesics (e.g., ibuprofen, codeine) may be necessary for a few days. Careful evaluation for underlying conditions should be undertaken in patients with severe or recurrent otitis externa. An approach to management is noted in Figure 631-1.

Other Diseases of the External Ear

Exostoses and Osteomas

Exostoses represent benign hyperplasia of the perichondrium and underlying bone (Chapter 495.2). Those involving the auditory canal tend to be found in people who swim often in cold water. Exostoses are broad-based, often multiple, and bilateral. Osteomas are benign bony growths in the ear canal of uncertain cause (Chapter 495.2). They usually are solitary and attached by a narrow pedicle to the tympanosquamous or tympanomastoid suture line. Both are more common in males; exostoses are more common than osteomas. Surgical treatment is recommended when large masses cause cerumen impaction, ear canal obstruction, or hearing loss.

Haddad JJr. Care of the draining ear in children. Emerg Pediatr. 1995;8:75.

Majumdar S, Wu K, Bateman ND, et al. Diagnosis and management of otalgia in children. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2009;94:33-36.

Nussinovitch M, Rimon A, Volovitz B, et al. Cotton-tip applicators as a leading cause of otitis externa. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:433-435.

Roland PS, Belcher BP, Bettis R, et alCipro HC Study Group. A single topical agent is clinically equivalent to the combination of topical and oral antibiotic treatment for otitis externa. Am J Otolaryngol. 2008 Jul–Aug;29(4):255-261.

Roland PS, Eaton DA, Gross RD, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled evaluation of Cerumenex and Murine earwax removal products. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:1175-1177.

Roland PS, Stroman DW. Microbiology of acute otitis externa. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1166-1177.

Rosenfeld RM, Brown L, Cannon CR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:S4-S23.

Siddiq MA, Samra MJ. Otalgia. BMJ. 2008;336:276-277.

Van Balen FAM, Smit WM, Zuithoff PA, et al. Clinical efficacy of three common treatments in acute otitis externa in primary care: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;327:1201-1203.

Wall GM, Stroman DW, Roland PS, et al. Ciprofloxacin 0.3%/dexamethasone 0.1% sterile otic suspension for the topical treatment of ear infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:141-144.