Exposure of the Common Femoral Artery and Vein

Femoral Anatomy

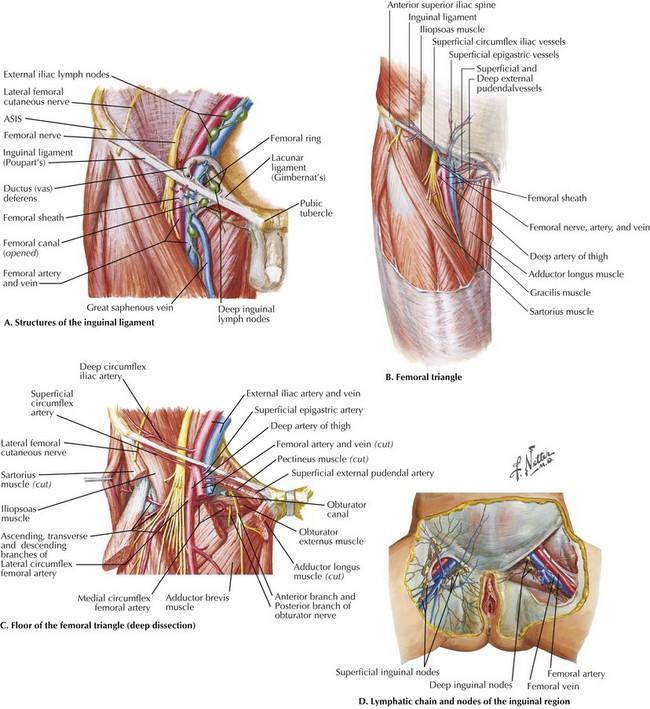

The CFA measures approximately 5 cm and is the direct continuation of the external iliac artery, distal to the inguinal ligament. The femoral neurovascular bundle emerges from the retroperitoneum of the pelvis at the inguinal level on its way into the thigh. Just as the umbilicus is located toward the midline, the mnemonic NAVEL refers to these structures deep to the inguinal ligament, from lateral to medial: femoral Nerve, common femoral Artery (CFA), common femoral Vein (CFV), Empty space in femoral canal containing lymph vessels and lymph nodes, and lacunar Ligament (Fig. 37-1, A).

The inguinal (Poupart’s) ligament, which spans from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the pubic tubercle, also forms the superior border of the femoral triangle (Fig. 37-1, B). The lateral and medial borders are the sartorius and adductor longus muscles, respectively. The femoral triangle appears as a depressed plane on thigh flexion and external rotation and contains the femoral neurovascular bundle, including the two major CFA branches, the femoral and profunda femoris (deep femoral) arteries and their corresponding veins. Proximally, deep to the NAVEL structures, the floor of the triangle comprises, from lateral to medial, the iliopsoas and pectineus muscles and pectineal ligament condensation on the superior pubic ramus (Fig. 37-1, C). The roof of the triangle is formed by fascia lata of the thigh, which has an oval opening at the superomedial aspect (fossa ovalis) through which the greater saphenous vein and lymphatic vessels join the deeper structures. Lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes are oriented parallel to the CFA and CFV, as well as along the inguinal ligament (Fig. 37-1, D).

Surgical Principles

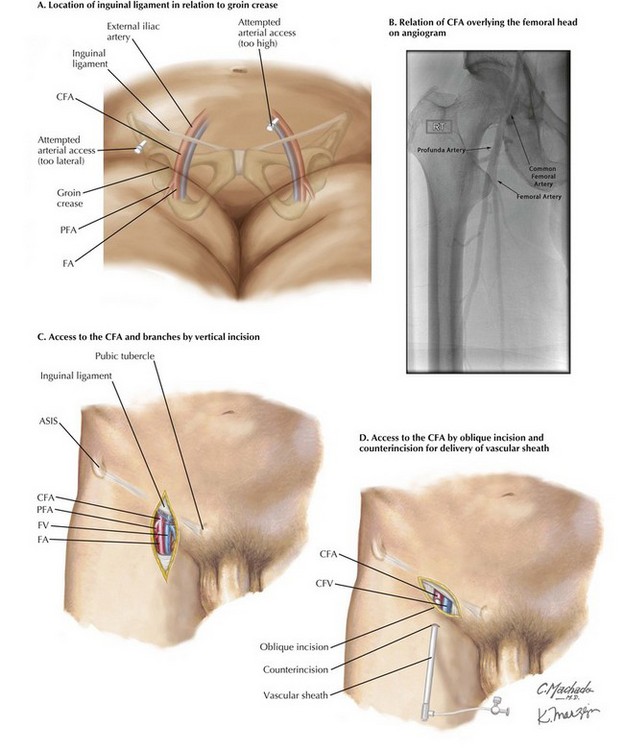

The location of CFA for percutaneous access is usually guided by palpation of its pulse, typically located just medial and inferior to the midpoint of the inguinal ligament. A common misconception that leads to low arterial sticks and possible injury to the femoral or profunda artery is that the groin crease directly corresponds to the inguinal ligament (Fig. 37-2, A). The inguinal ligament is two to three fingerbreadths cephalad to the crease and is most reliably identified by bony landmarks (ASIS, pubic tubercle) on palpation or fluoroscopy. The CFA usually overlies the medial two thirds of the femoral head (Fig. 37-2, B). These guidelines are helpful when the CFA is pulseless (heavy calcification, severe stenosis) or indiscernible (body habitus, obesity).

FIGURE 37–2 Accessing the femoral artery.

ASIS, Anterior superior iliac spine; CFA, common femoral artery; CFV, common femoral vein; FA, femoral artery; FV, femoral vein; PFA, profunda femoris artery.

Incisions and Closure

Operative exposure of the CFA can be achieved through vertical or oblique incisions. A vertical incision is favored if access to the CFA, femoral artery, and profunda femoris artery (PFA) is required. The PFA takeoff is usually 3 to 5 cm below the inguinal ligament in a posterolateral direction. The vertical extent of skin incision can therefore be adjusted to the required level of dissection (Fig. 37-2, C). Dissection in a vertical plane lessens inadvertent transection of lymphatic vessels that travel parallel to the CFA. Along with meticulous ligation of lymphatic tissue before transection, complications (lymphatic leak, lymphocele) and subsequent wound infection can be minimized.

Oblique incisions should be made at a level between the groin crease and inguinal ligament, overlying the CFA. This technique is favored if only a segment of CFA is required, such as for delivery of aortic endografts. A separate skin incision inferiorly can be made to allow tunneling of the endograft delivery device (vascular sheath) through subcutaneous fat to reach the CFA at a suitable entry angle (Fig. 37-2, D).

Major Arterial Branches

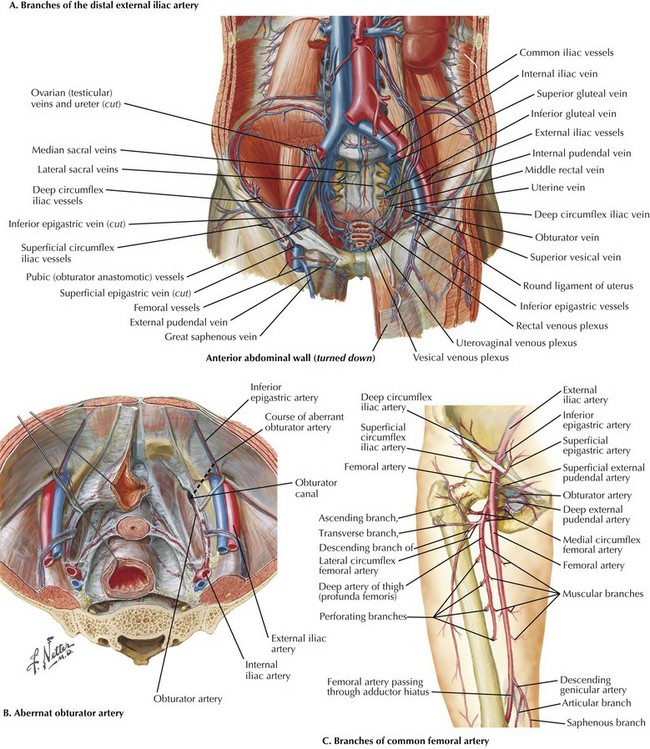

The distal external iliac artery gives off two small branches, the inferior epigastric artery and the deep circumflex iliac artery, which runs between the peritoneum and transversalis fascia just cephalad to the inguinal ligament (Fig. 37-3, A). The inferior epigastric artery supplies the lowest part of the rectus abdominis muscle, entering at the level of the arcuate line. An aberrant obturator artery may be present in 20% of cases, originating from the inferior epigastric artery instead of the internal iliac artery. This aberrant obturator artery is prone to injury during bypass graft tunneling (aortofemoral or iliofemoral) or femoral hernia repairs, because it lies across the femoral canal and pectinate line, coursing to exit at the obturator foramen (Fig. 37-3, B). The deep circumflex iliac vessels, especially the vein, are also prone to injury because they course along the lateral portion of the inguinal ligament. Control of the vein by division between silk ties is recommended before blunt tunneling of the retroperitoneum from the femoral triangle into the abdomen, to accommodate a bypass graft.

The CFA gives rise to three superficial branches that emerge through the deep fascia of the femoral sheath and thigh (fascia lata), to supply the subcutaneous tissue and skin of the lower abdomen and upper thigh: superficial epigastric, superficial external pudendal, and superficial circumflex iliac arteries (Fig. 37-3, C). These arteries may develop to become prominent collateral branches in peripheral vascular occlusive disease and therefore should be preserved as much as possible. Their corresponding veins converge at the greater saphenous vein (GSV) close to the saphenofemoral junction. Dissection along any of these tributaries in a central direction can help identify the GSV if needed as a vein conduit for bypass surgery.

Avoiding the Common Femoral Artery

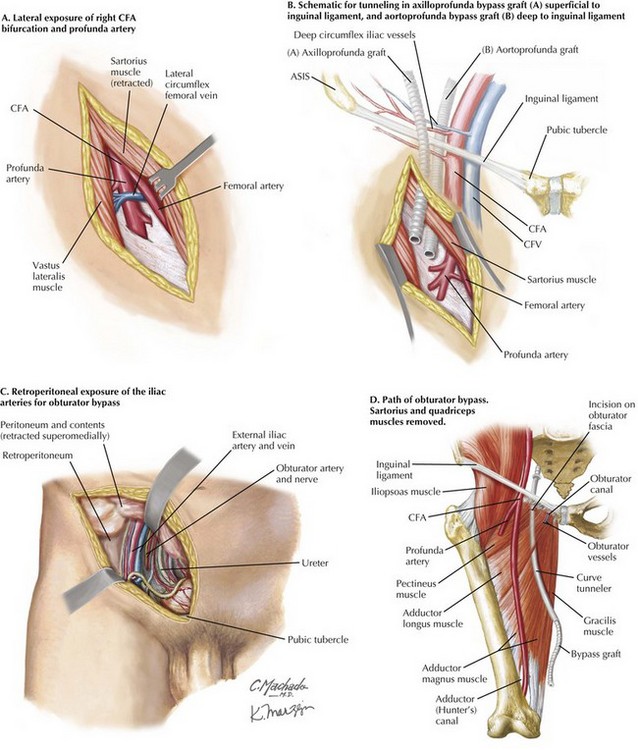

When avoiding the CFA is indicated, as in redo surgery and extensive scarring, the PFA may be an adequate recipient vessel for bypass with a slanted incision along the lateral border of the sartorius muscle. Dissection of the CFA bifurcation and proximal PFA can be achieved deep to the sartorius (Fig. 37-4, A). The bypass graft can be tunneled more laterally toward the ASIS, superficial to the inguinal ligament in an axillo-PFA bypass, or deep to the ligament in an aorto-PFA bypass (Fig. 37-4, B).

FIGURE 37–4 Avoiding the femoral artery.

ASIS, Anterior superior iliac spine; CFA, common femoral artery; CFV, common femoral vein.

In the more morbid situation of graft infection involving the groin area, after complete excision of infected graft material and debridement of infected tissue, revascularization can also be achieved with an obturator bypass. The obturator artery is best approached with a lower-quadrant incision along the direction of the external oblique muscle fibers. The internal oblique and transversalis muscles are divided and the peritoneum and its contents are retracted superomedially to expose the retroperitoneum and iliac vessels (Fig. 37-4, C). The surgeon passes the bypass conduit through the central portion of the obturator fascia, taking care not to injure the obturator artery and vein passing into the obturator canal. Using a curved tunneler, the surgeon can bring the graft behind the pectineus and adductor muscles to the midthigh for anastomosis with the femoral artery, or to the adductor canal for anastomosis with the supragenicular popliteal artery (Fig. 37-4, D).

Lawrence, RF. Arterial bypass through the obturator foramen. In: Baker RJ, Fisher JE, eds. Mastery of surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001:2109–2114.

McMinn, RMH. Lower limbs. In Last’s anatomy: regional and applied, 9th ed, London: Churchill Livingstone; 1994:145–170.

Valentine, RJ, Wind, GC. Common femoral artery. In Anatomic exposures in vascular surgery, 2nd ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2003:375–411.