Assessment of (un)fitness for work 371

The words ‘expert assessment’ here refer to any medical evaluation of a patient in terms of fitness for work and potential employment and in terms of any insurance-related issues in the particular case in question.

9.1. Assessment of (un)fitness for work

The most numerous category of patients suffering from pain originating in the locomotor system comprises those with back pain. While their lives are not endangered, they may nevertheless not be fit for the work they are expected to perform, temporarily or permanently, and in some cases they are even threatened with invalidity. In addition, there is the question of harm traceable to the type of work they do, or to occupational injury, sometimes involving litigation with claims for compensation. All these aspects have to be assessed by an expert.

If the assessment is to be scientifically based, it must take account of the pathogenesis, evolution, and prognosis of the condition. Our experience with reflex therapy and with manual therapy in particular has modified our views concerning pathogenesis, leading us to conclude that function is the decisive factor here. Since it is precisely this aspect that must be reflected in any expert assessment, the considerable difficulties are obvious.

One problem is that patients have often not received either adequate therapy or rehabilitation. This scenario will continue for as long as there are only relatively few physicians who understand how to diagnose and treat locomotor system dysfunctions adequately. In this highly regrettable situation significant lesions may pass unnoticed, and this is a particularly serious consequence in view of the principal symptom, that is pain. A physician who is unfamiliar with the diagnosis of painful trigger points (TrPs), tension, and resistance in the tissues has to rely on the patient’s own description of the symptoms. The physician then has the choice of either believing the patient or not. When called upon to provide an expert opinion, the physician tends to search for objective criteria, in the misguided belief that these are supplied by X-ray examination findings. However, any changes detected in that way are primarily morphological. Because this approach is consistent with conventional, received wisdom it is psychologically advantageous. The patient is informed, more often than not, of the changes found on X-ray and these are presented as the true cause of the pain, thus confirming the patient’s own ideas about the significance and potential duration of the underlying condition. It then becomes very difficult to motivate the patient concerning the benefits of an arduous rehabilitation program.

On the other hand, young patients with serious pain that is often of a radicular nature are considered to be malingerers because their X-rays show ‘no degenerative changes’. In recent years, despite significant advances made in the fields of computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound, not much has altered; indeed, if anything, the situation has become even more complicated. It is beyond the capability of any imaging technique to demonstrate the relevance of morphological changes, that is to show whether the patient has a herniated disk or ‘merely’ narrowing of the spinal canal. If no radicular syndrome is present, even a herniated disk may be irrelevant. These findings, obtained using the most up-to-date and most expensive techniques, divert attention away from gross yet highly relevant dysfunctions.

It is therefore important to give some indication here of how an expert assessment can and should be performed with regard to disturbed function. While we cannot deal with all types of pain caused by locomotor disturbance, we will focus primarily on back pain and radicular syndromes, because these are the commonest causes of unfitness for work that necessitate expert assessment. Because expert assessment is chiefly called for in conditions with a chronic or chronic relapsing course, we will deliberately not be considering acute cases. It is also important to exclude pathological conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis, tuberculosis, osteoporosis, etc.

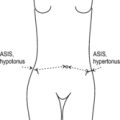

Chronic disease courses without pathomorphological findings are characterized by decompensation due to dysfunctions of muscles, joints, or soft tissues, by faulty statics, or by muscle imbalance. The chief concern must be to correct these, so as to reverse the pattern of dysfunction, while at the same time assessing to what extent the work the patient is expected to perform contributes to this decompensated state. This assessment of the locomotor system has to be performed specifically in each individual case.

For instance, if a patient consistently develops back pain after sitting for extended periods, there should be a (temporary) ban on sedentary work but walking should be encouraged if the patient feels comfortable with this. First, however, a check must be made to ensure that the bad effects of sitting are not due to an unsuitable chair or to a table at the wrong height. Similarly, if the symptoms are produced by bending down, lifting, or carrying loads, it must be established whether the patient’s corresponding movement patterns are at fault – in which case these must be corrected. Steps should also be taken to ensure that the patient returns to work as soon as possible after learning how to perform these activities correctly.

If the symptoms are due to lack of exercise, we should be reluctant to forbid movement, even if it is perceived to be unpleasant. It should not cause a sensation if a patient who is signed off sick from work is spotted walking in the countryside or even moving about on skis so as to get fit.

Sometimes unfitness for work is caused not by the patient’s work itself, but by how the patient travels to and from work, particularly if the journey involves being jolted about.

Here again it is important to distinguish between (low-)back pain, with or without pain referred to the lower extremities, and true radicular pain. In the former case, movement (especially walking) is usually very well tolerated and should be encouraged, while in the acute stage of a radicular syndrome it may be harmful. Patients with degenerative joint disease involving the lower extremities do not tolerate walking (or standing) for long periods, especially on hard paved surfaces or concrete.

There is a specific problem in the case of patients who have been unfit for work for a long period due to a radicular syndrome, particularly where an operation has been necessary. These people are out of training. If a young athlete, for example, were confined to bed for several weeks or months, nobody would expect them to be ready to compete again straight away. However, people with physically demanding jobs do not enjoy the same consideration, although it should be obvious that a period of adaptation is necessary if they are to train themselves up to the same level of efficiency as before. If we do not want to run the risk of relapse, it is helpful if the patient works for a time under somewhat easier conditions, that is either part-time or omitting some of the more demanding operations involved, until full work fitness is regained.

Even though they are equally intense, pain in the low back and the lower extremities is a more frequent cause of work incapacity than pain involving the neck, head, or upper extremities; this is because intense low-back or lower extremity pain may prevent the patient from standing or walking. Pain of cervical origin may result in unfitness for work if the job demands full use of the hands or if the nature of the work considerably aggravates the pain. (As an aside, pain is often more bearable if the patient is not alone and resting or ‘taking things easy’.)

From all that we have noted so far, it is evident that in terms of function it is possible for the expert to make a concrete assessment of the demands imposed on the patient by a particular type of work and to relate these demands to the patient’s symptoms and capabilities. In this way the patient can be helped far more efficiently to overcome those symptoms produced by locomotor system dysfunctions or by adverse circumstances in the workplace.

Before turning to the much-discussed question of trauma, it will be appropriate to say a few words about the harmful effects of certain types of work per se. In the preceding chapter we noted the unfavorable repercussions on the locomotor system of most forms of work in our technologically developed world. Having said that, there are certain occupations that appear to be particularly vulnerable from this point of view: drivers, particularly those exposed to severe jolting, as in a tractor; people whose jobs involve extreme static overstrain, for example long hours of computer work in an ergonomically unsound position; and production line workers who have to perform rapid hand movements for hours at a time (repetitive strain injuries). Even so, it seems premature to regard back pain as an occupational disease.

Frequently, symptoms develop if patients are engaged in work for which they are clearly unsuited physically. This should be prevented by screening employees in the workplace when they are first taken on. Worst affected are older employees who find it hard to adapt and have to move to another job. They then rightly claim that symptoms appeared or got much worse because of their new job. However, the real fault lies in lack of prevention.

9.2. Assessment of trauma and its consequences

Because an accident, and particularly an accident in the workplace, may give the patient the right to claim compensation, this is a frequent area for litigation and one that requires expert assessment. The expert needs to consider two main questions: (1) Did an accident really happen? and (2) Was the alleged accident responsible for the patient’s condition, and to what extent? Both these questions may be contentious and therefore both will be explored here.

9.2.1. Did an accident happen?

If a heavy object falls on someone’s toe and causes fracture, nobody would question that the fracture was due to injury. When someone bends forward to lift a heavy object, the force generated in the trunk on straightening up may amount to several hundred kilograms. If in such a situation a sudden, uncoordinated, jerky movement occurs, for example if the person slips or unexpectedly lets go of the load, the dynamic forces brought to bear on the lumbosacral junction may be even greater.

It would be illogical not to regard the sudden, unexpected effect of such a force as an injury. We know from experience that sometimes it will not be easy to determine with certainty precisely which mechanism actually caused the alleged injury because most injuries affect the spinal column indirectly. If, therefore, symptoms pointing to spinal involvement occur after a fall on to the buttocks, shoulders, or head, they should be considered as a consequence of the trauma, even if the patient is unaware of the connection. The greater the damage to the structure directly injured, the easier it will be for indirect spinal involvement to be overlooked. Immediately after fracture of the humerus or pelvis, local pain is such that it draws all attention to the major trauma, while the insidious concomitant injury to the spinal column is barely noticed. In the cervical spine, this same phenomenon is often seen in whiplash-type injury. After the fracture has healed, the vertebrogenic symptoms deteriorate and often assume a chronic course. It is also not sufficiently recognized that a fall on to the shoulder or a blow on the head (e.g. in boxing) can have an effect similar to that of whiplash injury after a classic rear-end automobile impact.

It should be recalled that although a patient’s symptoms after trauma are frequently due to disturbed function, only relatively few physicians have the skills needed to accurately diagnose locomotor system dysfunctions. And it can be particularly difficult to recognize hypermobility resulting from trauma. It may easily happen therefore that patients who have suffered injury end up ‘merely’ with disturbance of function. If they then complain of symptoms, they are dismissed as having ‘no objective signs of illness’, their pain is labeled as ‘psychological’ and in the worst-case scenario they may even be accused of malingering. Inevitably, patients register this and feel a deep sense of injustice. A typical conflict then ensues, in which patients tend to come off worse, eventually reacting in a neurotic and usually inappropriate way, and sealing their own fate. The diagnosis is then one of ‘pain behavior’, although this is often the result of physician ignorance regarding dysfunctions that are eminently treatable.

9.2.2. Did the accident cause the symptoms?

Where trauma as such has been admitted, the question then to be answered is whether the patient’s symptoms are indeed the result of the accident. This is a difficult question in some circumstances, for example if symptoms do not follow immediately after the accident and if there is a symptom-free interval of days, weeks, or even months. We know that the immediate result of an accident may be ‘merely’ disturbance of function and that this may not become clinically manifest for some time, being triggered, for example, by a sudden movement or by additional strain.

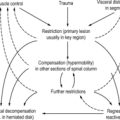

Another contentious issue is whether the trauma affects a structure that was completely intact, or whether the structure now affected has previously been injured. This question is frequently put in cases of elderly patients in whom degenerative changes are usually already present. It is reasonable to argue that trauma impacting an intact structure should cause less harm than if there was previous damage to the structure. In the first case there is ‘merely’ a (reversible) dysfunction that, if treated adequately, should recover in time without sequelae. In the second case (with the previously damaged structure), even if the patient was symptom-free prior to injury, there were probably compensatory mechanisms at work that were already functioning well; the subsequent trauma therefore brings about decompensation, which may be (and frequently is) a much more serious condition.

In actual fact, however, most expert assessors arrive at the opposite conclusion. They reason that in view of the demonstrable morphological (i.e. degenerative) changes, the patient would sooner or later have developed the same symptoms, and therefore the trauma did not produce the symptoms but merely caused a clinically latent disorder to become manifest. The same thinking is also used to explain the clinical manifestation of intervertebral disk herniation. Again the argument runs like this: trauma affecting an intact spinal column is more likely to result in fracture of the vertebra than in disk herniation. If, however, signs of disk degeneration are already present, prolapse with its clinical consequences would have occurred anyway, so that again the trauma would have been no more than a precipitating factor.

The above reasoning can be criticized point by point, as follows:

1. There are conditions under which a disk may prolapse even if intact. This occurs when a force impacts the disk in lordosis or hyperlordosis, as is known from those tragic accidents when an adolescent diver’s head strikes the bottom of a pool. Acute herniation of the disk then compresses the spinal cord, resulting in quadriplegia. In this process the vertebrae remain intact and the radiological appearance is normal.

2. Disk degeneration is a very common condition, as confirmed by radiological evidence of such in the majority of persons studied over 50 years of age. Yet relatively few suffer from any clinical manifestations at all, let alone from radicular pain.

3. Even if a disk has prolapsed, it may be asymptomatic: disk herniation is often an opportunistic finding at autopsy in subjects who never suffered radicular pain (McRae 1956). Currently, thanks to CT or MRI, we are detecting increasing numbers of herniated disks that are clinically irrelevant, that is the patient’s symptoms have cleared up. This serves to confirm the commonly opportunistic nature of this finding, as pointed out by McRae more than half a century ago.

It is therefore untenable to argue that particular morphological, mainly degenerative changes are necessarily predictive of certain clinical conditions. This applies not only to the ‘degenerative’ changes themselves but also to the disk lesions associated with them.

In principle, it is wrong to assess the consequences of trauma as ‘less serious’ simply because pre-existing degenerative changes have been demonstrated. To follow that line of reasoning may give rise to a number of potential anomalies, as illustrated in the following example. A young injury victim with an intact locomotor system would receive extremely generous compensation, even though recovery from the consequences of trauma is normally quite straightforward. By contrast, an older injury victim with no symptoms up to the time of the accident (i.e. because of good adaptation to any pre-existing degenerative changes) is likely to show functional deterioration following trauma. This individual would receive relatively little financial compensation despite the fact that recovery from injury will be far more difficult than in the case of the younger colleague.

The crucial question then is: what are the criteria for providing an expert assessment in the field of locomotor system dysfunctions? The basis here should be the clinical examination because this offers insight into the significance of any dysfunctions present and provides a measure of the intensity of the reflex changes that are the direct expression of the pain or nociceptive stimulus.

However, the true role played by trauma is determined primarily on the basis of the case history: according to the criteria set out in this chapter, did the trauma really occur and was the patient in fact symptom-free up to the time of the accident? If the answer is yes on both counts, then the trauma must be recognized as having caused the patient’s symptoms. The pain-free interval between the occurrence of trauma and the onset of symptoms should be relatively brief and not longer than a few weeks. On the other hand, if the patient already had symptoms before the accident and the clinical course alternated between typical episodes and remissions, then the trauma was at most a precipitating cause, and even then only if the pain occurred shortly afterward. And this is irrespective of the presence or absence of degenerative changes on X-ray. As most employed persons are registered with a physician, it is not usually difficult to establish how often the patient sought medical help for pain even before the accident and whether the symptoms had previously necessitated the patient being signed off sick.

Trauma impacting a previously damaged but compensated spinal column will have more serious repercussions than trauma impacting an intact spinal column. The fact that a patient shows evidence of pre-existing degenerative changes in no way justifies the assumption that symptoms and/or disk herniation would eventually have occurred anyway. A useful criterion here is the presence of similar symptoms prior to the accident.