Clinical examination of the temporomandibular joint

Pain

Pain in the TMJ area usually has a local cause and is seldom referred to any distance.

Pain referred from the temporomandibular joint

Pain of the TMJ structures may arise from the masticatory muscles or from the joint itself. The main inert structures that can give rise to pain are the intracapsular tissues located posterior to the condyle: the posterior part of the meniscus, the meniscus attachments to the capsule, the capsule and the retromeniscal fat pad.1 Pain is often accompanied by headache, earache or pain in the postauricular area. Pain arising from the TMJ sometimes refers to the maxilla.

Pain referred to the temporomandibular joint area

Neurological disorders

Trigeminal nerve neuritis

This may be encountered in patients of 45–60 years of age. It affects females more often than males and the right side more frequently than the left. The patients complain of unilateral shooting pain, from the ear towards the temporal area and the maxilla, sometimes even in the forehead and towards the pharynx. The cause of the pain may be so obscure that unnecessary dental extraction takes place. Pain is seldom accompanied by diminished sensitivity but characteristic trigger points are often found. Stimulation of these, even sometimes by light touch, results in pain felt elsewhere, which is followed by a refractory period of up to 30 seconds during which stimulation does not lead to new pain. The pain attacks seldom last longer than a few seconds. They may recur at irregular intervals, sometimes on a daily, weekly or even a monthly basis. They are isolated or come on in clusters.2

Herpes zoster oticus infection

This can give rise to dysaesthesia preceding the characteristic vesicles. No true trigger points are present. About 15% of all peripheral facial palsies is caused by this virus.3

Non-neurological disorders

Cluster headache (Horton’s neuralgia)

This predominantly affects males, is unilaterally localized, and is associated with increased lachrymation, rhinitis and ipsilateral facial redness. Attacks of severe headache in or around the eyes, usually unilaterally, come on within 5–10 minutes and last from about 45 minutes to a few hours. Attacks occur in clusters.6

Temporal arteritis

This is one of the manifestations of a giant-cell arteritis, an autoimmune process.7 It is usually seen unilaterally in males over 50 years of age and is frequently associated with polymyalgia rheumatica. It is characterized by a knocking pain around the temporal vessels. The skin overlying the artery is red, swollen and warm. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is raised.

Leaking cerebral aneurysm

It has an explosive onset of headache, nausea and vomiting, together with photophobia and stiffness of the neck. Aneurysm at the level of the posterior communicating artery may be followed by pain in the first division of the trigeminal nerve. It is the commonest cause of so-called ophthalmoplegic migraine.8

History

As well as taking a history of pain, a number of other aspects should be discussed with the patient:

• Does the joint click? In an anterior subluxating meniscus, the normal relation between meniscus and condyle is disturbed, giving rise to a click on opening the mouth.

• Is movement limited, either in range or by locking? If there is a diminished range of opening of the mouth, did the limitation come on suddenly or was it more progressive? If ‘sudden’ locking is mentioned, can the patient still open or close the mouth? Inability to open suggests meniscus displacement, which is usually unilateral, and in which at least 1 cm of mouth opening is always retained. If closing is impossible, a luxation of the mandibular condyle is most likely. Excessive limitation coming on rapidly may be the result of hysteria or of tetanus; mouth opening is impossible in these circumstances. A limitation of slow development is usually the outcome of arthrosis of the TMJ.

• Is there crepitus? Crepitus is the result of movement across an irregular surface because of advanced changes in the joint. It may be present in osteoarthrosis.

• Does the patient suffer from clenching or grinding? This occurs mainly at night in stressed people. The patient may not be aware of it, relatives may have to be asked.

• Is there tinnitus, vertigo or a hearing problem? Vertigo may result from differences in vestibular impulses as a result of TMJ problems. Other symptoms, such as mild deafness, a sensation of fullness in the ear and tinnitus, may also be present.

• Have there been changes in sensibility? These can indicate peripheral neuropathy. It frequently affects the lips, cornea and conjunctivae. In atypical facial neuralgia, severe diminished facial sensibility is often found. Trigeminal neuritis is seldom accompanied by disturbed sensibility.

Inspection

Swelling may be the result of a bacterial or an inflammatory arthritis (frequently rheumatoid, seldom due to psoriasis or gout), or in children10 may be caused by an inflammation of the parotid gland.

Severe inflammatory disorders of the TMJ area during childhood may result in asymmetrical development of the lower face because of disturbance of the growth centre in the mandible. Advanced arthrosis may lead to asymmetry of face and head and to narrowing of the external auditory canal. Synovitis usually causes an ipsilateral deviation when the mouth is opened and a contralateral deviation when closed.9

Functional examination

Active movements

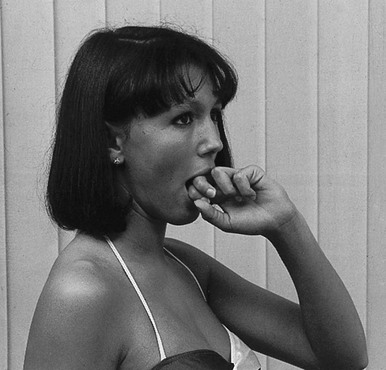

Active opening of the mouth (Fig. 1)

Because it is difficult to measure the range of motion of the TMJ in degrees, the interincisal distance at maximum opening is used. It is about 36–38 mm in adults but may vary between 30 and 67 mm, depending on sex and age.11,12 A practical and quick way of checking range of motion is to ask the patient to insert the knuckles in between the front teeth (Fig. 2).

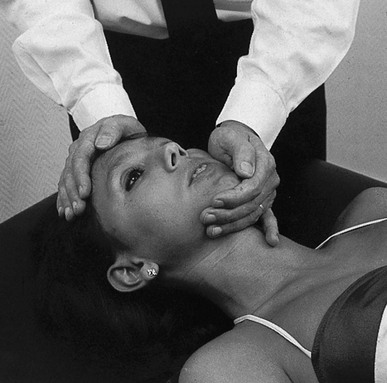

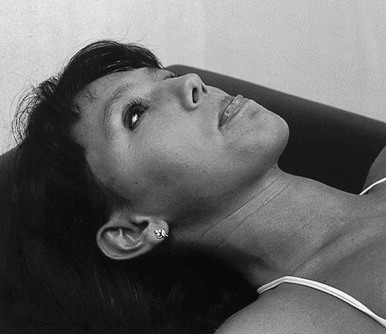

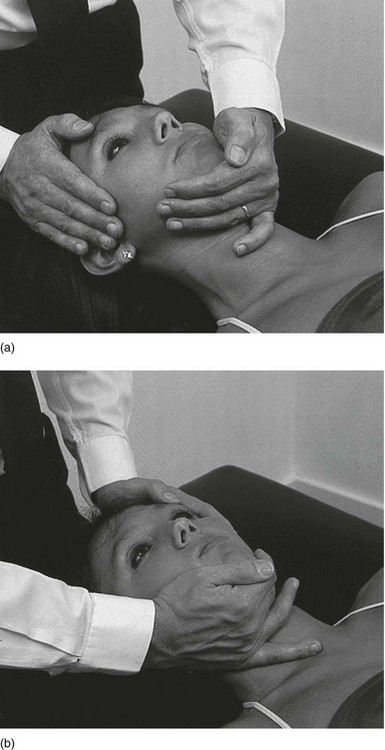

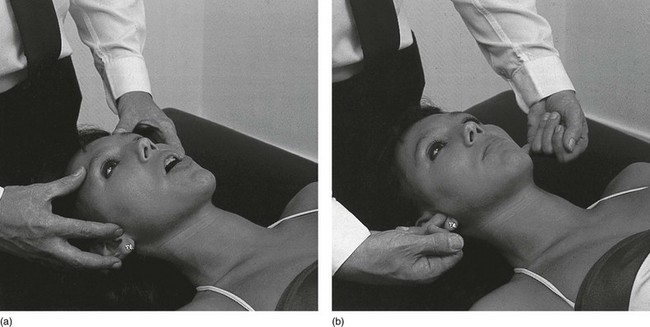

Palpation

On opening, the TMJ is palpated with the finger below the zygomatic bone just anterior to the condyle or, as for closing, with the tip of the finger placed either just anterior to the tragus (Fig. 9a) behind the condyle or in the external auditory meatus (Fig. 9b), exerting some anterior directed pressure against the posterior aspect of the joint. The examiner normally feels a depression on opening. If a severe effusion is present, a bulge may be palpated. Attention must be paid to abnormal sounds and crepitus and to the anteroposterior gliding movement of the condyle.

Technical investigations

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is frequently elevated in systemic diseases and infections.

Plain radiography does not provide much information except for evidence of arthrosis.13 A CT scan can determine more accurately the position and condition of the meniscus and the joint.14,15

In recent years, magnetic resonance imaging has been increasingly used to investigate temporomandibular disorders, for example internal derangement.16–18

References

1. Rocabado, M, Arthrokinematics of the temporomandibular joint. Dental Clin North Am. 1983;27(3):573–594. ![]()

2. Fromm, GH, Terrence, CF, Maroon, JC, Trigeminal neuralgia: current concepts regarding etiology and pathogenesis. Arch Neurol 1984; 41:1204–1207. ![]()

3. Adour, KK, Current concepts in neurology: diagnosis and management of facial paralysis. New Engl J Med 1982; 307:348–351. ![]()

4. Adour, KK, Wingerd, J, Idiopathic facial paralysis (Bell’s palsy): factor affecting severity and outcome in 446 patients. Neurology 1974; 24:1112–1116. ![]()

5. Adour, KK, Byl, FM, Hilsinger, RL, Jr., Kahn, ZM, Sheldon, MI, The true nature of Bell’s palsy: analysis of 1000 consecutive patients. Laryngoscope 1978; 88:787–801. ![]()

6. Kudrow, L. Cluster Headache: Mechanisms and Management. London: Oxford University Press; 1980.

7. Mumenthaler, M, Giant-cell arteritis: cranial arteritis, polymyalgia rheumatica. J Neurol 1978; 218:219–236. ![]()

8. Mumenthaler, M. Circulatory disturbances and hemorrhages of the brain. In Neurology, 3rd ed, New York: Thieme; 1990:93.

9. Hodges, JM, Managing temporomandibular joint syndrome. Laryngoscope 1990; 100:60–66. ![]()

10. De Bont, L, Stegenga, B, Boering, G, Kaakgewrichtsstoornissen. Deel I, Gedachtenontwikkeling en classificatie. Ned Tijd Tandheelkd 1989; 96:496–500. ![]()

11. Mezitis, M, Rallis, G, Zachariades, N, The normal range of mouth opening. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1989; 47:1028–1029. ![]()

12. Claes, J. Het temporomandibulair pijndysfunctiesyndroom in otorhinolaryngologie. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. 1981; 35(2):170–183.

13. Hansson, LG, Hansson, T, Petersson, A, A comparison between clinical and radiological findings in 259 temporomandibular joint patients. J Prosthetic Dentistry 1983; 50:89–94. ![]()

14. Helms, CA, Morrish, RB, Kircos, LT, Katzberg, RW, Dolwick, MF, Computed tomography of the meniscus of the temporomandibular joint. Preliminary observations. Radiology 1982; 145:719–722. ![]()

15. Raustia, AM, Phytinen, J, Virtanen, KK, Examination of the temporomandibular joint by direct sagittal computed tomography. Clin Radiol 1985; 36:291–296. ![]()

16. Kircos, LT, Ortendahl, DA, Mark, AS, Arakawa, M, Magnetic resonance imaging of the TMJ disc in asymptomatic volunteers. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 45:397–401. ![]()

17. Schellhas, KY. Imaging of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1989; 1:13–26.

18. Eberhard, D, Bantleon, HP, Steger, W, Functional magnetic resonance imaging of temporomandibular joint disorders. Eur J Orthodon. 2000;22(5):489–497. ![]()