Clinical examination of the shoulder girdle

Symptoms referred to the shoulder girdle

Shoulder girdle movements are therefore included in both the cervical (see Chapter 6) and thoracic (see Chapter 25) examinations. This preliminary screening may arouse suspicion about the shoulder girdle.

History

History-taking will therefore start in the same way as for the examination of the cervical (see Chapter 6) or thoracic spine (see Chapter 25) or of the shoulder (see Chapter 12). The examiner will notice elements that may lay blame on the spinal joints (e.g. pain shifting from the centre to one side) or features that point towards a lesion of the shoulder girdle (e.g. increase of symptoms following scapular movements).

Functional examination

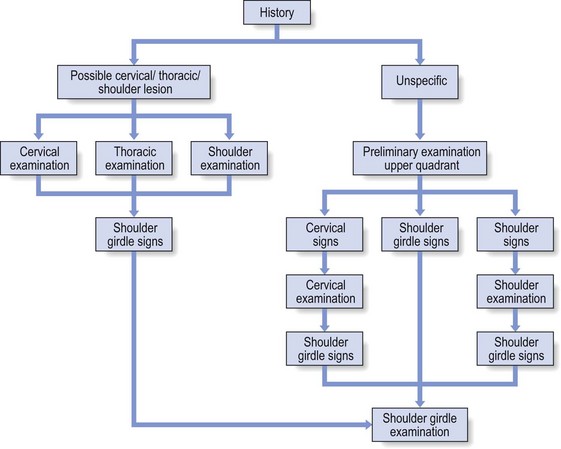

When the history is unspecific a preliminary examination (quick survey) of the upper quadrant is done (see p. 212). This includes tests for:

Functional examination of the shoulder girdle is very simple: three active, three passive and four resisted movements are performed (see Fig. 1), summarized in Box 1.![]()

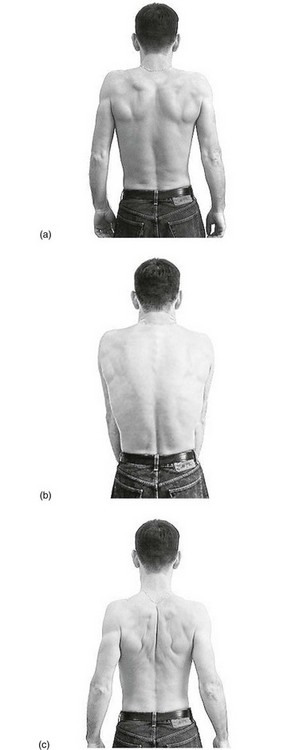

Active movements

The active tests cause movement in the three primary articulations. During all active movements (Fig. 2), attention is paid to pain, range of motion and abnormal sensations, such as paraesthesia or crepitus. The movements may stretch inert or contractile structures and make muscles work. A decreased range of movement is usually the result of either a neurological disorder or a problem of an inert structure.

Active protraction of both shoulders

The patient brings both shoulders forwards. The normal range of scapular abduction is about 30°.

Active retraction of both shoulders

The patient is asked to pull both shoulders backwards. Normally, about 30° is possible.

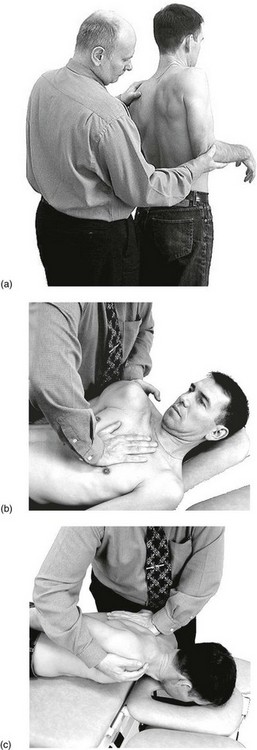

Passive movements

For a clear differential diagnosis between disorders of inert and contractile structures, active tests must be followed by passive and resisted movements. Passive movements (Fig. 3) put local inert structures under tension, have some influence on the joints at both ends of the clavicle and may passively stretch some contractile structures. Because the scapula glides on the thorax during these movements, the scapulothoracic gliding surface also must function properly.

Passive elevation of the shoulder

The examiner stands behind the patient, places one hand underneath the flexed elbow and brings the shoulder up by an upward directed pressure on the olecranon. The other hand fixates at the contralateral side of the base of the neck (Fig. 3a).

Passive protraction of the shoulder

The patient is supine. The examiner stands at the patient’s painful side and asks the patient to bring the shoulder forwards actively. The ipsilateral hand on the sternum is used for fixation, with the contralateral hand on the scapula. The patient is then asked to relax and the examiner continues the movement passively to the end of range where an extra pressure is given to assess end-feel (Fig. 3b).

Passive retraction of the shoulder

The patient is asked to lie prone with the arm on the back. The examiner, at the patient’s painless side, asks the patient to pull the shoulder actively backwards and then places the contralateral hand at the spine and fixes that area. The ipsilateral hand lies at the anterior aspect of the shoulder. The patient is asked to relax and the examiner continues the movement passively to the end of range where an extra pressure is given for the judgement of the end-feel (Fig. 3c).

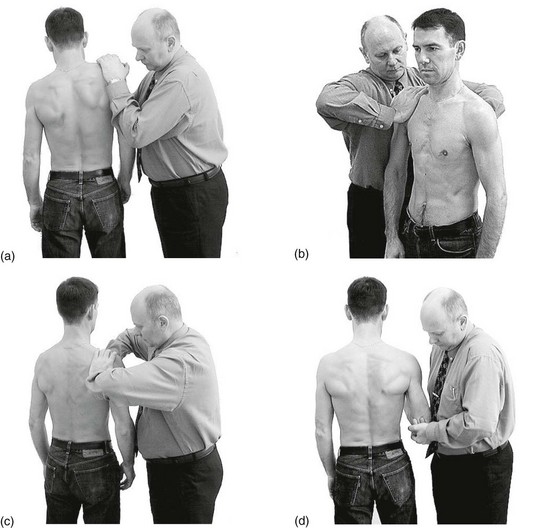

Resisted movements

During resisted movements (Fig. 4) pain and weakness are assessed.

Fig 4 Resisted movements of the shoulder: (a) elevation; (b) protraction; (c) retraction; (d) depression.

Resisted elevation of the shoulder

The examiner stands at the patient’s painful side and puts both hands on the shoulder. The patient is asked to shrug the shoulder against the examiner’s resistance (Fig. 4a). This movement tests the levator scapulae and the upper part of the trapezius, as well as the integrity of the C2–C4 nerve roots.

Resisted protraction of the shoulder

The examiner stands at the patient’s side and puts one hand on the anterior aspect of the shoulder, the other one on the posterior thorax between the scapulae. The patient is now asked to press the shoulder forwards (Fig. 4b). This is a test for the pectoralis major, serratus anterior and pectoralis minor muscles.