Examination

introduction

Introduction

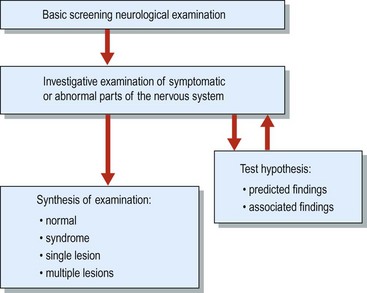

The examination is used, like the history, as a screening test and as an investigative tool (Fig. 1). In patients in whom you anticipate a normal examination (e.g. migraine or epilepsy), a simple screening examination is appropriate (Box 1). The examination is used to investigate the hypotheses generated by the history and to clarify and understand any abnormalities found on the screening examination. For example, sensory examination of the hand will need to be done carefully in a patient with sensory symptoms affecting the hand; this would not be done in the same detail in a patient who presented with blackouts.

Box 1 Screening neurological examination

Mouth – ‘open your mouth (look at tongue) and say ‘arrh’ (observe palate). Please put out your tongue’

Mouth – ‘open your mouth (look at tongue) and say ‘arrh’ (observe palate). Please put out your tongue’ Arms

Arms

Legs

Legs

When considering the examination as a whole you should try to answer the following questions:

General examination

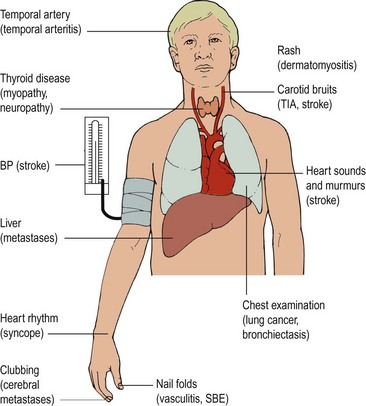

The general examination (Fig. 2) is important for several reasons. It may provide clues to the cause of the neurological disorder or uncover risk factors. For example, finding a breast mass in a woman with a progressive hemiparesis suggests there are cerebral metastases; raised blood pressure and hypertensive retinopathy indicate hypertension as a significant risk factor in a patient with a stroke. General examination may reveal conditions associated with the neurological problem, for example finding peripheral vascular disease in a patient with transient ischaemic attacks. General examination can also find other unrelated important diseases that may affect the management of the neurological condition: for example, a patient with difficulty walking and lumbar canal stenosis who was also found to have significant osteoarthritis of the hip may benefit more from a hip replacement than from lumbar canal decompression.

Patients in whom stroke or a transient ischaemic attack is being considered in the differential diagnosis need a careful examination of the cardiovascular system.

Patients in whom stroke or a transient ischaemic attack is being considered in the differential diagnosis need a careful examination of the cardiovascular system. Patients who present with possible metastases need examination to try to identify the likely primary tumour.

Patients who present with possible metastases need examination to try to identify the likely primary tumour.There are several conditions that come to mind as soon as you see the patient – if they don’t come to mind then they can be difficult to find. These include hypothyroidism, acromegaly, myotonic dystrophy and Parkinson’s disease.

Organization of the examination

Neurological examination findings are presented in a traditional way (Box 2). This has developed because it is easier to make sense of what can be quite a large amount of information if it is provided in a standard way. While most neurologists will examine patients broadly following this conventional order, most have developed their own habits. One I know starts his examination at the feet! You need to develop (and practise) your own order and system of examination.

Mental state examination

The mental state examination is conducted along with the history. It is useful to have a mental framework for areas to consider in a patient with an altered mental state (Table 1). In patients in whom the changes result from neurological disease, it is important to obtain independent corroboration of any change in personality, delusions and so on.

| Heading | Consider | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance and behaviour | Does he or she seem anxious or depressed? Does his or her behaviour seem appropriate? Do moods swing? | Ask relatives and make your own assessment |

| Mood | Is the patient depressed? Does the patient see any hope in the future? | Ask the patient directly and also form an impression from your own observations |

| Delusions | Belief, not amenable to argument, not usual in patient’s culture | Revealed by the patient in the history. Cannot be sought directly |

| Hallucination | Classify according to sensory modality affected (visual, auditory, etc.) Elementary or complex? | |

| Vegetative symptoms | Appetite, weight, constipation, libido |