9 Evidence-based practice and research

Clinical Practice Guideline: Systematically developed statements or guides designed to provide a key link between evidence-based knowledge and health care practice and to offer a mechanism to advance the quality and equity of patient care through the translation of evidence to practice.1–3

Evidence-Based Practice: The conscientious and judicious use of current best available evidence in conjunction with clinical expertise and patient values or preference to guide the care given to patients.1,4–6

Experimental Design: A study whose purpose is to test cause-and-effect relationships, specifically to examine the effects of an intervention or treatment on selected outcomes. An experimental design always includes an intervention and control group with random assignment to groups.1,4

Metaanalysis: A technique for quantitatively integrating the results of multiple similar studies addressing the same research question to produce a single estimate of the effect of the intervention of interest.4

Nonexperimental Design: Also called an observatory or exploratory study, a non-experimental design is a study in which data are collected regarding a phenomena without the introduction of an intervention by the researcher.1,4

Prospective Study: Follows patients forward in time, with the use of carefully defined protocols to determine an outcome that is unknown beforehand. This powerful type of research allows the determination of cause-and-effect relationships.4

Qualitative Research: The investigation of phenomena using an in-depth and holistic approach, often involving personal interviews and observations.1,4

Quantitative Research: The investigation of phenomena involving the use of precise measurement and manipulation of numeric data via statistical analysis.1,4

Quasiexperimental Design: A type of design that examines the effect of an intervention on an outcome but lacks one or more characteristics of a true experimental design.1,4

Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial: Patients are randomly assigned to a control (receiving the standard treatment or placebo) or intervention group (receiving the new or experimental treatment), and the outcome is measured and compared. Such trials are considered the most reliable and impartial method of determination of treatment effectiveness.1,4

Retrospective Study: Looks backward in time, usually with use of medical records or existing databases. This type of study is weaker than a prospective study and permits one to determine only the nature of association between a treatment and outcome.1,4

Systematic Review (Integrative Review or Metasynthesis): A rigorous and systematic review of the literature on a like topic involving a clearly defined method for identifying, appraising, and synthesizing the literature and drawing conclusions regarding the question of interest.1,4

Overview of evidence-based practice

EBP involves the conscientious and judicious use of the most current and best available evidence along with the clinician’s expertise and consideration of the patient’s values and preferences to provide patient care.1,4–6 Evidence-based care has been recognized by the Institute of Medicine as a critical component of safe, quality patient care.7 Despite the emphasis on evidence-based care and the millions of dollars spent in the development and conduct of research designed to improve patient care,8 it can take as long as 15 years for this newly discovered knowledge to be translated to clinical practice.9–11

Nursing has a long history of applying evidence to practice, dating back to the days of Florence Nightingale; however, little recognized progress was made in the formal EBP movement until the development of the Cochrane Collaboration, established by Archie Cochrane in the early 1970s in the United Kingdom. As this collaboration was evolving, a similar movement was evolving at the McMaster Medical School in Canada. Originally designated as evidence-based medicine, the concept has shifted over time to be referred to as evidence-based practice and is inclusive of all health care disciplines.1,4,5

The process of evidence-based practice

There are many models to guide the process of EBP. Some of the best known models include the Iowa Model of EBP,12,13 the Hopkins Model of EBP,14 the Melnyk/Fineout-Overholt model,1 and the Rosswurm and Larrabee model.15,16 Steps common to all EBP models include1,12,14,15:

1. Identify the problem or need for change.

4. Critically appraise and synthesize the evidence.

5. Design the practice change.

7. Evaluate the outcomes of the practice change.

Identify the problem or need for change

The first step in the EBP process is to identify the problem or need for change. Problem identification or “triggers” for change can arise from many sources and can be either knowledge or problem focused.12 Problem-focused triggers typically arise from clinical problems or data. Perhaps performance improvement data shows an increase in surgical site infection, or clinical observation shows that female laparoscopic patients are having a higher incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) then other patients. Knowledge-focused triggers arise when a nurse or another member of the health care team gains new knowledge about current practice that may show improved patient outcomes. This knowledge may arise from reading journal articles or attending a conference.12 After the problem is identified, it is important to form a work team that is inclusive of all involved stakeholders. Organizational support, to include commitment of all necessary resources, inclusive of employee time to work on the project, should also be obtained.12,15

Refine the question

One of the most critical components of the EBP process is to form a focused, searchable, answerable clinical question. Successful completion of this task will literally drive the continued evolution of the project. A strong question typically addresses at least four major components (Box 9-1): the patient (or population), intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO). A fifth component that may be included is time (PICOT).1

BOX 9-1 PICO Components

From Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E: Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: a guide to best practice, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2011, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

When the PICO components have been defined, the next step is to organize them into a question. The most common EBP questions are focused on either an intervention, prognosis or prediction, diagnosis or diagnostic test, or etiology.1 Templates for developing questions using identified PICO components are provided in Box 9-2. Box 9-3 provides an example of the process.

BOX 9-2 PICO Question Templates

Intervention: In P, what is the effect of I compared with C on O?

Prognosis and prediction: In P, how does I compared with C influence or predict O?

Diagnosis or diagnostic Test: In P, what is the accuracy of I compared with C in diagnosing O?

From Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E: Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: a guide to best practice, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2011, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Polit DF, Beck CT, editors: Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, Philadelphia, 2008, Lippincott Willims & Wilkins.

Locate the evidence

Key sources of evidence include evidence-based guidelines, evidence-based reviews such as Cochrane Reviews, and original research articles and reviews published in journals. These sources can be located by searching databases and government or specialty practice websites.17,18 It is always recommended that multiple databases be searched; however, searches of certain databases or other sources may be more productive depending on the type of question posed (Table 9-1).

Table 9-1 Databases and Other Sources for Conducting Literature Searches

| DATABASE OR SOURCE | TYPE OF INFORMATION | ACCESS |

|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) | Excellent database for more nursing focused questions | www.cinahl.com (subscription required) |

| MEDLINE | Developed by the National Library of Medicine; recognized as the premier source for biomedical literature | www.pubmed.gov |

| Cochrane Databases | Database of all Cochrane reviews; excellent source for systematic reviews | www.cochrane.org |

| Joanna Briggs Institute | International source for evidence-based guidelines | www.joannabriggs.edu.au |

| National Guideline Clearinghouse | Hosted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; free clearinghouse of clinical practice guidelines | www.guideline.gov |

| Specialty practice organizations such as ASPAN, ANA, AORN, and SAMBA | Provide evidence-based guidelines or practice recommendations regarding various aspects of anesthesia and perianesthesia care | Access via each organizational web site |

Modified from Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E: Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: a guide to best practice, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2011, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Polit DF, Beck CT, editors: Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, Philadelphia, 2008, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Ehrlich-Jones L, et al: Searching the literature for evidence. Rehabil Nurs 33:163–169, 2008; Fineout-Overholt E, et al: Teaching EBP: getting to the gold: how to search for the best evidence. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2:207–211, 2005.

The process of locating the best evidence is driven by the formulation of a solid question. The PICO components of the question provide the key search terms as well as guides for limiting or narrowing your search. The ideal approach would be to engage the services of a medical librarian who is familiar with EBP searches. The reality, however, is that such resources might not be readily available to the bedside nurse. The first step to embarking on a successful search strategy is to identify the key search terms unique to your particular question. It is often helpful to begin this process by taking the time to make a list of key search words or terms. The most successful searchers are general driven by at least two or three key search concepts.17 This list should be driven by the PICO components of your question. Using the example question in Box 9-3, key search words would include acupressure and PONV. Other useful search terms may include postoperative, postanesthesia, nausea, vomiting, and complications. Because PONV can occur in both adult and pediatric populations, it may also be helpful to use the adult population as a search limit.

In most databases, these key search terms will automatically map to medical subject headings, also known as MeSH terms.17 For example, if PONV is not a MeSH term in the database that you are searching, it may automatically map to nausea, vomiting, or postoperative complications. It is recommended that one use the “explode” option for the primary search terms, and then use features such as combining search results using and or or to further narrow the results. For example, should the search term PONV map to a MeSH heading of postoperative complications, it may be helpful to fully explode this term, as well as the terms nausea and vomiting. is the next step is to combine the three terms (i.e., postoperative complications, nausea, vomiting) using and to narrow the search to literature specific to PONV. Combine this narrowed search result with the results from the search on the term acupressure to capture the literature addressing the use of acupressure for the prevention or treatment of PONV (see Box 9-3). These results may then be narrowed by adult ages using the search limitation options.

If this initial search strategy yields a large number of results that would prohibit a comprehensive review of the references, it may be helpful to further limit the search by levels of evidence. EBP should be guided by the best available evidence. What is considered best is guided by the level of the evidence and its relationship to the question of interest. The level of evidence is ranked according to the type of evidence or research design. Numerous evidence hierarchies are available in the literature. All commonly rank systematic reviews, metaanalyses, and high-quality evidence-based clinical practice guidelines as the highest level of evidence, and expert opinion as the lowest level of evidence. A sample evidence hierarchy is provided in Table 9-2.

| LEVEL | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| I | Systematic review or metaanalysis of RCTs; evidence-based guidelines based on a systematic review process |

| II | Evidence from at least one RCT |

| III | Evidence from at least one quasiexperimental study |

| IV | Systematic review of descriptive or qualitative studies |

| V | Evidence from at least one nonexperimental study |

| VI | Evidence from at least one descriptive or qualitative study |

| VII | Expert opinion |

RCT, Randomized controlled trial.

Modified from Polit DF, Beck CT, editors: Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, Philadelphia, 2008, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Newhouse RP, et al: Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice model and guidelines, Indianapolis, 2007, Sigma Theta Tau; Fineout-Overholt E, Johnston L: Teaching EBP: asking searchable, answerable clinical questions, Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2:157–160, 2005; Krainovich-Miller B, et al: Evidence-based practice challenge: teaching critical appraisal of systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines to graduate students, J Nurs Educ 48:186–195, 2009; Jones KR: Rating the level, quality, and strength of the research evidence, J Nurs Care Qual 25:304–312, 2010.

Critically appraise and synthesize the evidence

The next step in the EBP process is to critically appraise and then synthesize the evidence. A thorough discussion of the specifics guiding the critical appraisal of various research designs is beyond the scope of this chapter. It is helpful to first break out each particular component of an article so that it is possible to easily analyze each section. Questions that can help in organizing an appraisal are outlined in Table 9-3.

| APPRAISAL QUESTION | APPLICATION TO YOUR EBP QUESTION |

|---|---|

| What is the research question or purpose of the article? | Does the question or purpose relate to your EBP question? |

| What is the study design? | |

| Who or what are the subjects or setting? | Are the subjects or setting similar to that of your EBP question? |

| What are the predictor (independent) variables? | Are these similar to factors affecting your EBP issue? |

| What are the outcome (dependent) variables? | Are these the same as the outcomes that you are interested in for your EBP question? |

| What type of analysis was conducted? | |

| Are there potential biases? | |

| What were the results? | Can you apply the results to your EBP question? |

EBP, Evidence-based practice.

From Ehrlich-Jones L, et al: Searching the literature for evidence, Rehabil Nurs 33:163–169, 2008.

Criteria guiding the critical appraisal and ranking of the quality of a piece of evidence are dependent on the type of evidence examined. Table 9-4 provides an overview of specific criteria that should be used to examine certain types of evidence, and Table 9-5 provides some general guidance in judging the overall quality of a specific type of evidence.

Table 9-4 Evidence-Specific Criteria for Appraising Quality

| EVIDENCE TYPE | APPRAISAL CRITERIA |

|---|---|

| Systematic review |

RCT, Randomized controlled trial.

Modified from Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E: Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: a guide to best practice, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2011, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Polit DF, Beck CT, editors: Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, Philadelphia, 2008, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Jones KR: Rating the level, quality, and strength of the research evidence, J Nurs Care Qual 25:304–312, 2010.

Table 9-5 Guidelines for Ranking Quality

| QUALITY LEVEL | EVIDENCE TYPE | CRITERIA |

|---|---|---|

| High | Systematic reviews | Well-defined, reproducible search strategy; consistent results across included studies; criteria-based evaluation of overall strength and quality of included articles; definitive conclusions |

| Research | Consistent results based on adequate sample size and control measures; consistent recommendations based on extensive literature review with thoughtful reference to current scientific evidence | |

| Expert opinion | Expertise clearly evident | |

| Good | Systematic reviews | Reasonably thorough and appropriate search; reasonably consistent results across studies; evaluation of strength and limitations of included studies; fairly definitive conclusions |

| Research | Sufficient sample size; some control; reasonably consistent results; fairly definitive results | |

| Expert opinion | Expertise appears to be credible | |

| Low or major flaws | Systematic reviews | Undefined, poorly defined, or inadequate search strategies; insufficient evidence with inconsistent results; unable to draw conclusions |

| Research | Insufficient sample size; numerous confounding variables; inconsistent results; unable to draw conclusions | |

| Expert Opinion | Expertise not discernable or dubious |

From Newhouse RP, et al: Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice model and guidelines, Indianapolis, 2007, Sigma Theta Tau.

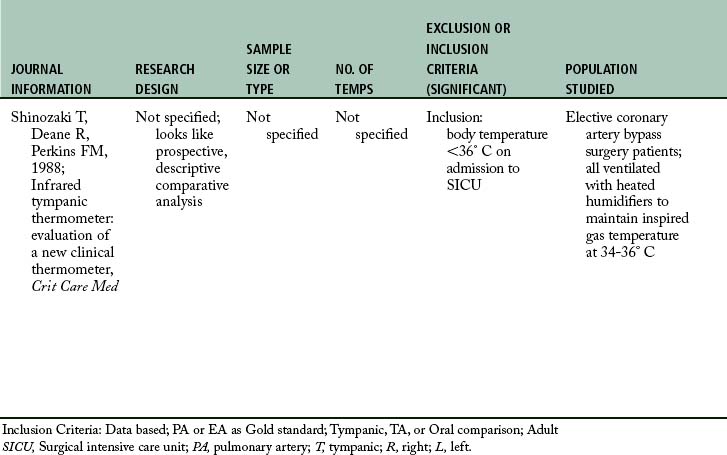

It may be helpful to organize this information in tables to better assimilate and synthesize the information.1,4,15,19 The first step in this process would be to develop evidence tables that include some of the basic evidence components of the article, to include the evidence level and quality ranking (Table 9-6). It may then be helpful to also develop tables summarizing the articles by interventions and specific outcomes of interest. This summary information will then help in interpreting what is and is not supported by the evidence, and thus guide recommended practice changes.

Design and implement the practice change

The next steps of the EBP process are to design and implement the practice change. The results of a critical appraisal and synthesis of the evidence should provide guidance in answering the PICO question, and thus identify the practice change that is indicated. In the case of the sample PICO question in Box 9-3, “In adult PACU patients, what is the effect of acupressure compared with routine care on the incidence of PONV,” the evidence search revealed a Cochrane Review that supported the effectiveness of acupressure in reducing the incidence of PONV. Because a Cochrane Review is of the highest level and quality of evidence available, one can be confident that the addition of acupressure should be effective in reducing the incidence of PONV in the adult PACU patient population.

If you have not already done so, one of the first steps in implementing a proposed practice change is to identify and engage all affected staff and stakeholders. From this group, formal implementation teams are built and change leaders or agents in the targeted implementation unit are identified. Build excitement about the change by identifying the relative advantage of the practice change, both for the practitioner and the patient. Discuss observable benefits. Design an education strategy that incorporates the advantages and benefits of the change and provides an overview of the where’s, how’s, and why’s associated with the proposed change. Listen to staff feedback as the change is previewed and adjust strategies as indicated by staff response and recommendation. Identify possible barriers to implementing the proposed change and develop strategies to help overcome these variables such as technological resources, reminder tools, and documentation resources.1,15

When developing the implementation strategy for the practice change, also identify a target unit or patient population in which to first pilot the practice change. Using a targeted implementation plan will facilitate evaluation of outcomes and modification of the practice change or implementation strategy before going with facility-wide implementation. It is also important to collect preliminary outcome data before implementation of the practice change so that clinical outcomes can be compared before and after implementation.1,15

Evaluate the outcomes of the change

Outcomes of interest should be measurable and easily identified from the PICO question. The outcome of interest in the sample PICO question (Box 9-3), incidence of PONV, is easily measured. It is also likely that data regarding this issue can be easily abstracted from the medical record to allow for comparison before and after the practice change. Additional measurable outcomes that may also be examined for this question include number and amount of prophylactic or rescue antiemetics given, length of stay in the PACU or phase II setting, patient satisfaction, and overall cost of care. When outcome measures are finalized, a data collection cycle should be established that allows for inclusion of a large enough sample of patients to ensure a true evaluation of the effects of the practice change on targeted patient outcomes.1,15

In addition to a quantitatively focused outcome evaluation, it is also important to capture qualitative feedback from the major stakeholders and staff members, as well as patients and family members affected by the practice change, as appropriate. This type of evaluation allows for an opportunity to closely examine process and flow issues that might not be reflected by other outcome measures. This information may indicate the need to refine the implementation strategy before expansion of the practice change across multiple units in the facility.1,15

Adjust, integrate, and sustain change

When the proposed practice change has been piloted on a specific unit or target population and the results of that pilot have been analyzed, it is then time to make appropriate adjustments and expand the practice change to other appropriate units or patient populations in the facility. This project expansion requires continued engagement of all stakeholders and affected staff of all affected units. Minor adjustments to the practice change or implementation strategy may be indicated to incorporate needs of a specific unit or patient population. Monitoring of outcome data as well as process and structure issues should also be continued throughout the implementation stage, and then on a periodic basis postimplementation to assure sustainability and incorporation into the practice culture.15

Disseminate outcomes

Outcome dissemination should incorporate numerous internal and external strategies. Daily or at least weekly feedback will be indicated on individual units as the practice change is implemented to allow for celebration of successes and rapid resolution of identified problems. As the practice change is expanded throughout the facility, larger celebrations of success may be indicated to reward good practice and improved patient outcomes. It is also important that the process and outcomes are disseminated outside of the facility via poster and podium presentations as well as journal articles.1,15 It is only through the sharing of EBP failures and successes that practice can continue to evolve and improve on a national and international level.

Relationship of evidence-based practice to bedside practice

EBP is the key link between knowledge generation and application of that knowledge to practice. It is the most critical component in improving the safety and quality of patient care,7 and it should be the standard of practice for all disciplines. EBP is a process that affords the opportunity to explore, implement, and assess interventions that are applied to the patient within the context of all available information. It represents a shift in the culture of health care provision away from exclusive opinion-based, past practice, and precedent decisions toward making health care decisions based on science, research, and evidence, while continuing to incorporate provider expertise and patient preference.

Summary

Today’s perianesthesia nurses have an enormous amount of information and experience (personal, collegial, published) from which to draw when providing patient care. Only through the thorough analysis and synthesis of the highest levels and quality of information available, however, can the perianesthesia nurse be assured of providing the highest quality of care available.

1. Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: a guide to best practice. ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2011.

2. Larson E. Status of practice guidelines in the United States: CDC guidelines as an example. Prev Med.2003;36(5):519–524.

3. Lia-Hoagberg B, et al. Public health nursing practice guidelines: an evaluation of dissemination and use. Public Health Nurs.1999;16(6):397–404.

4. Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Willims, & Wilkins; 2008.

5. Titler MG. The evidence for evidence-based practice implementation. Hughes RG, ed. Patient safety and quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, Md: AHRQ; 2008;vol 1:113–161.

6. Sackett DL, et al. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. ed 2. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

7. Institute of Medicine: Crossing the quality chasm a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

8. Dufault M. Testing a collaborative research utilization model to translate best practices in pain management. Worldviews on evidence-based nursing. 2004;1:S26–S32.

9. Dobbins M, et al. A framework for the dissemination and utilization of research for health-care policy and practice. The Online Journal of Knowledge Synthesis for Nursing. 9(7), 2002.

10. Donaldson NE, et al. Outcomes of adoption: measuring evidence uptake by individuals and organizations. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing.2004;1:S41–S51.

11. Olsen L, et al. The learning healthcare system: Workshop summary (IOM roundtable on evidence-based medicine). available at: http://books.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=11903, April 9, 2009. Accessed

12. Cullen L, Adams S. An evidence-based practice model. J Perianesth Nurs. 2010;25(5):307–310.

13. Titler M, et al. The Iowa model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America. 2001;13:497–509.

14. Newhouse RP, et al. Johns hopkins nursing evidence-based practice model and guidelines. Indianapolis: Sigma Theta Tau; 2007.

15. Larrabee JH. Nurse to Nurse: Evidence-Based Practice. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2009.

16. Rosswurm MA, Larrabee JH. Clinical scholarship: A model for change to evidence-based practice. Image: journal of nursing scholarship.1999;31(4):317–322.

17. Ehrlich-Jones L, et al. Searching the literature for evidence. Rehabil nurs. 2008;33(4):163–169.

18. Fineout-Overholt E, et al. Teaching EBP: Getting to the goldhow to search for the best evidence. Worldviews on evidence-based nursing.2005;2(4):207–211.

19. Fineout-Overholt E, et al. Evidence-based practice, step by step: critical appraisal of the evidencepart III. Am.2010;110(11):43–51.

21. Krainovich-Miller B, et al. Evidence-based practice challenge: teaching critical appraisal of systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines to graduate students. Journal of nursing education.2009;48(4):186–195.

22. Jones KR. Rating the level, quality, and strength of the research evidence. J nurs care qual. 2010;25(4):304–312.