CHAPTER 68 Evidence-based care in gynaecology

Introduction

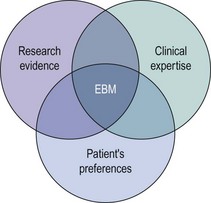

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been defined as the ‘conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’ (Sackett et al 1996). It incorporates three fundamental elements: external research evidence, clinical expertise, and patients’ views and values in the delivery of health care (Figure 68.1).

Evidence-Based Medicine Processes

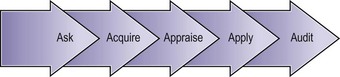

A fifth ‘A’ for ‘Audit’ can be added to these steps to take EBM beyond the care of the individual patient (Figure 68.2).

Formulation of a structured question

A well-structured question is essential in order to get the right clinical answer. It also facilitates the process of searching for evidence. A suggested approach uses five components (PICOD: Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome(s) and Design), as shown in Table 68.1.

| Component | Example 1 | Example 2 |

|---|---|---|

| P: Population, patient or problem | In women suffering with heavy menstrual bleeding… | In postoperative women with swollen legs… |

| I: Intervention (test, medical or surgical treatment, or process of care) | … would treatment with norethisterone… | … would a Doppler ultrasound be accurate… |

| C: Comparison (placebo, another alternative treatment or the gold standard in a diagnostic accuracy study) | … compared with no treatment at all or alternative treatments (e.g. levonorgestrel IUS)… | … compared with venography as the gold standard… |

| O: Outcome(s) | … lead to an improvement in their symptoms? | … in diagnosing deep venous thrombosis? |

| D: Ideal design for the study | A randomized controlled trial | A test accuracy study |

IUS, intrauterine system. Produced by Bob Phillips, Chris Ball, Dave Sackett, Doug Badenoch, Sharon Straus, Brian Haynes, Martin Dawes since November 1998. Updated by Jeremy Howick March 2009.

Searching the literature

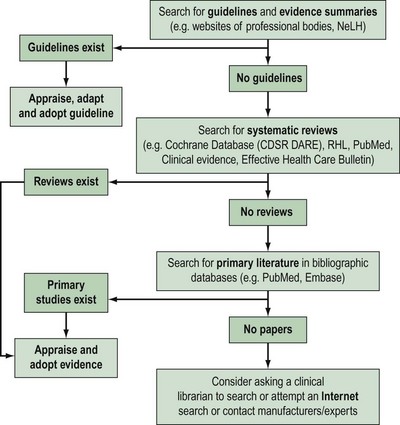

Approximately 17,000 journals collectively publish over 1 million biomedical articles each year. Identifying relevant articles will require the use of apposite keywords (and their combinations) to search appropriate databases. A hierarchical approach to literature searching is recommended (Figure 68.3).

The first step is to look for an up-to-date professional guideline that has been developed on the basis of systematic appraisal of available evidence. Table 68.2 lists some sources of guidelines and evidence summaries. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) has long acknowledged the need to update clinical practice on the basis of research findings. Since 1973, the RCOG has regularly convened study groups to address important growth areas within the specialty. These groups have met, evaluated the results of research and conducted in-depth discussions on a variety of topics. These discussions have shaped the development of clinical recommendations which were initially based on consensus. Over the years, this approach has been modified in order to produce genuine evidence-based guidelines. To be effective and relevant, guidelines must fulfil fthe following three essential criteria.

Table 68.2 Sources of guidelines and evidence summaries (relevant for gynaecology)

| Sources of guidelines and evidence summaries | Website |

|---|---|

| Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) | www.rcog.org.uk |

| American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) | www.acog.org |

| The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) | www.sogc.org |

| The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) | www.ranzcog.edu.au |

| International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) | www.figo.org |

| Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FFPRHC) | www.ffprhc.org.uk |

| British Fertility Society (BFS) | www.britishfertilitysociety.org.uk |

| British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) | www.bgcs.org.uk |

| British Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (BSCCP) | www.bsccp.org.uk |

| British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG) | www.rcog.org.uk/bsug |

| British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (BSGE) | www.bsge.org.uk |

| The Association of Early Pregnancy Units (AEPU) | www.earlypregnancy.org.uk |

| The NHS National Library for Health (NLH) | www.library.nhs.uk |

| The National Institute for Health Clinical Excellence (NICE) | www.nice.org.uk |

| Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) | www.sign.ac.uk |

| NHS Clinical Knowledge Summaries (NHS CKS; formerly PRODIGY) | www.cks.library.nhs.uk |

| The National Guideline Clearing House (NGC, US) | www.guidelines.gov |

In the absence of credible evidence-based guidelines, the next step would be to search for an up-to-date, good-quality, systematic review. Some sources of systematic reviews are given in Table 68.3.

Table 68.3 Sources of evidence

| Systematic reviews | |

|---|---|

| Sources of systematic reviews | Website |

| The Cochrane Library | www.cochrane.org/reviews/ |

| The CRD databases (including DARE) | www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb |

| The Pubmed Systematic Reviews Search Filter | www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query/static/clinical.shtml |

| Bandolier | www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier |

| The WHO Reproductive Health Library (RHL) | www.rhlibrary.com |

| Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database | www.ncchta.org/project/htapubs.asp |

| Sources of primary literature | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sources of primary literature | Subject matter | Website |

| Pubmed (Medline) | Medicine, bioscience | www.pubmed.gov |

| EMBASE | Medicine, pharmacology, nursing | www.embase.com |

| CINAHL | Nursing and allied health care | www.cinahl.com |

| AMED | Allied and alternative health care | www.bl.uk (search for ‘AMED’) |

| BNI (British Nursing Index) | Nursing | |

| HMIC (Health Management Information Consortium) database | Health management | |

WHO, World Health Organization; CRD, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; DARE, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness.

Apart from the traditional sources of systematic reviews, such as the Cochrane Library and DARE, MEDLINE and Pubmed have now become a rich source of systematic reviews. Pubmed contains a systematic review filter within Pubmed Clinical Queries (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query/static/clinical.shtml), and MEDLINE has the indexing term ‘reviews, systematic’ as a ‘publication type’.

If no systematic reviews are identified, or if reviews are out-of-date, non-systematic or of marginal relevance to the clinical question, it is necessary to continue the literature search for primary studies. Table 68.3 provides a list of important sources of primary literature.

Evaluation of the literature

Various checklists can be used to appraise different types of clinical questions. Checklists for therapeutic and diagnostic questions as well as systematic reviews are given in Tables 68.5, 68.7 and 68.10. In appraising a study, it is important to assess the suitability of the research design and methods used in the context of the specific clinical question. Randomized trials provide the best evidence for treatment, but valid evidence for diagnosis, prognosis and causation may be derived from publications based on other study designs (Table 68.4).

| Clinical question | Ideal research design |

|---|---|

| Effectiveness of therapy | RCT |

| Prevention | RCT |

| Screening | Cluster RCT |

| Diagnosis (accuracy) | Cross-sectional study (comparison of index test with reference standard test) |

| Prognosis | Cohort study |

| Aetiology | Case–control or cohort study |

| Adverse events | Case report, case series, case–control studies, cohort studies and RCTs |

| Economic assessment of medical interventions |

RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Appraising a paper on effectiveness of therapy (randomized controlled trial)

A randomized controlled trial reduces the risk of bias (systematic deviations or errors in the results) by minimizing the likelihood of important differences between the treatment and control arms of the study. If no randomized controlled trials are available, other research designs (e.g. a non-randomized controlled study or even a case–control study) may provide valuable information about therapy, although they may exaggerate the potential benefits of treatment and thus represent a lower grade of evidence (see evidence grades, Centre for Evidence-based Medicine, Oxford University, www.cebm.net) (see Appendix). A checklist can be used to appraise a therapy article (Table 68.5).

Table 68.5 Critical appraisal checklist for randomized controlled trials

* These items do not strictly relate to ‘validity’; nevertheless, they are important and should be part of the appraisal process.

If the results for a randomized controlled trial are dichotomous (i.e. a ‘yes/no’ outcome), and there are two arms in the study, the findings can be presented and analysed in a 2 × 2 table, as shown in Table 68.6.

Table 68.6 2 × 2 table to present the results of a two-arm trial with a dichotomous outcome

| Outcome (live birth) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Event | Non-event | |

| Experimental group (surgery for endometriosis) | a | b |

| Control group (no surgery) | c | d |

Appraising a diagnostic article

The checklist shown in Table 68.7 can be used to appraise a diagnostic accuracy article. It should be noted that this checklist only applies to accuracy studies; there are other aspects of testing that may need to be judged on other criteria. For example, evaluating the inter- or intraobserver reliability or the clinical impact of testing will require designs other than the one employed for accuracy evaluation, and will often need to be judged by other criteria.

Table 68.7 Critical appraisal checklist for diagnostic accuracy studies

| I. Are the results valid? |

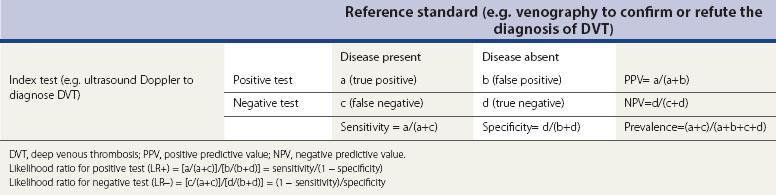

The sensitivity, specificity, predictive values and prevalence are defined in the marginal cells of Table 68.8. The sensitivities and specificities are often misinterpreted, and the mnemonics ‘SnNout’ and ‘SpPin’ are very useful to ensure correct interpretations.

Likelihood ratios, which can be calculated from the 2 × 2 table, or derived from sensitivities and specificities as shown in the footnote of Table 68.8, are generally considered to be the most useful of all test accuracy summaries. The likelihood ratio indicates how much a given test result raises or lowers the probability of having the disease. The higher the likelihood ratio of an abnormal test, the greater the value of the test. Conversely, the lower the likelihood ratio of a normal test, the greater the value of the test. Although a guide to the interpretation of likelihood ratios is provided in Table 68.9, it should be noted that the value of a test may vary depending on the pretest probability and the consequences of having the condition.

Table 68.9 Interpretation of likelihood ratios (LR)

| LR for positive test | LR for negative test | Value of test |

|---|---|---|

| >10 | <0.1 | Very useful |

| 5–10 | 0.1–0.2 | Moderately useful |

| 2–5 | 0.5–0.2 | Somewhat useful |

| >1–2 | 0.5–<1 | Little useful |

| 1 | 1 | Useless |

Appraising a systematic reviews or meta-analysis

The checklist in Table 68.10 can be used to appraise a systematic review.

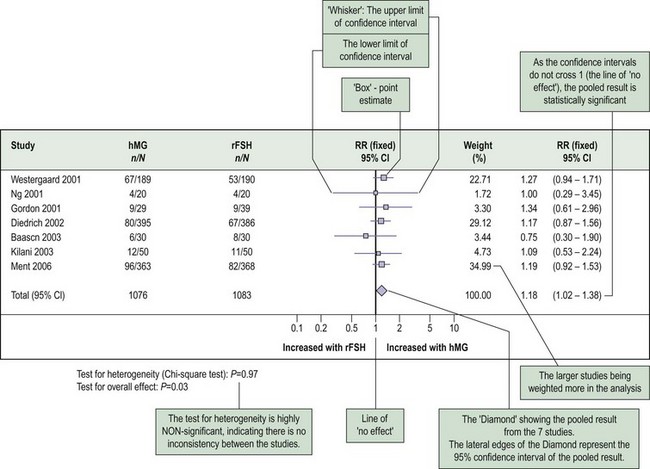

Findings of a meta-analysis are often presented as a forest plot (Figure 68.4). Forest plots can be used to plot relative risks, risk differences, odds ratios, mean differences or other summary estimates such as sensitivities, specificities and likelihood ratios. Each individual study in the systematic review is represented in a row, with its own point estimate (the ‘box’) and the 95% confidence interval (the ‘whiskers’). The pooled summary estimate is shown as a diamond at the bottom of the chart. The centre of the diamond represents the pooled estimate and the ends of the diamond represent the 95% confidence interval for the pooled estimate.

Implementation of useful findings

What does the patient think?

Despite being accessed and appraised systematically, most research findings are currently applied intuitively. If EBM is to be seen through to its logical conclusion involving a synthesis of empirical evidence and human values, the current conflict between the explicit collection of data and its implicit use must be addressed. This area is being investigated and possible options are being evaluated. These include decision analysis, which provides an intellectual framework for the development of an explicit decision-making algorithm (Lilford et al 1998), and computerized decision support systems. When there are several treatment options which may have different effects on a patient’s life, there is a strong case for offering patients a number of choices. It is possible that their active involvement in the decision-making process may actually increase the effectiveness of the treatment (Coulter et al 1999).

Conclusion

KEY POINTS

| A | Consistent level 1 studies |

| B | Consistent level 2 or 3 studies or extrapolations from level 1 studies |

| C | Level 4 studies or extrapolations from level 2 or 3 studies |

| D | Level 5 evidence or troublingly inconsistent or inconclusive studies of any level |

‘Extrapolations’ are where data are used in a situation that has potentially clinically important differences from the original study situation.

Coulter A, Entwistle V, Gilbert D. Sharing decisions with patients: is the information good enough? BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1999;318:318-322.

Coomarasamy A, Afnan M, Cheema D, et al. Urinary hMG versus recombinant FSH for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation following an agonist long down-regulation protocol in IVF or ICSI treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction. 2008;23(2):310-315.

Khan KS, Coomarasamy A. Searching for evidence to inform clinical practice. Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2003. Doi:10.1061/j.curobgyn.2003.12.006

Lilford RJ, Pauker SG, Braunholtz DA, Chard J. Decision analysis and the implementation of research findings. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1998;317:405-409.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71-72.

Guyatt G, Rennie D, O’Meade M, Cook DJ. JAMA Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature. A Manual for Evidence-based Clinical Practice. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008.

Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH. Physicians’ and patients’ choices in evidence based practice. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 2002;324:1350.

Khan KS, Coomarasamy A. Searching for evidence to inform clinical practice. Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2003. Doi:10.1016/j.curobgyn.2003.12.006.

Straus SE, McAlister FA. Evidence-based medicine: a commentary on common criticisms. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2000;163:837-841.

Straus SE, Richardson WS, Glasziou P, Haynes RB. Evidence-based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM, 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005.