Chapter 637 Evaluation of the Patient

Immunofluorescence Studies

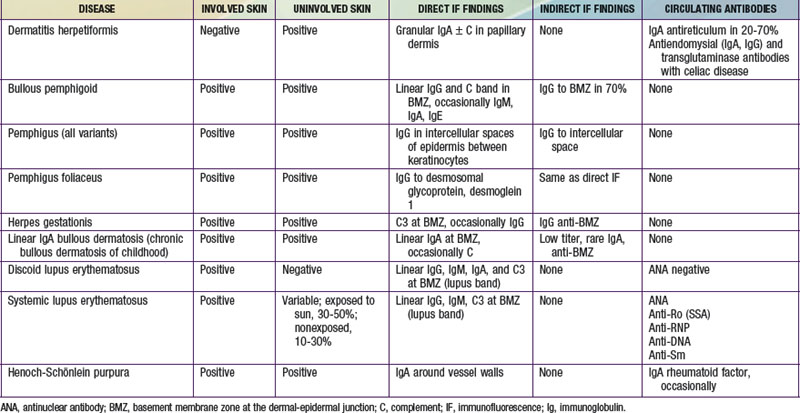

Immunofluorescence studies of skin can be used to detect tissue-fixed antibodies to skin components and complement; characteristic staining patterns are specific for certain skin disorders (Table 637-1). Serum can be used for identifying circulating antibodies. Skin biopsy specimens for direct immunofluorescence preparations should be obtained from involved sites except in those diseases for which perilesional skin or uninvolved skin is required. A punch biopsy sample is obtained, and the tissue is placed in a special transport medium or immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for transport or storage. Thin cryostat sections of the specimen are incubated with fluorescein-conjugated antibodies to the specific antigens.

637.1 Cutaneous Manifestations of Systemic Diseases

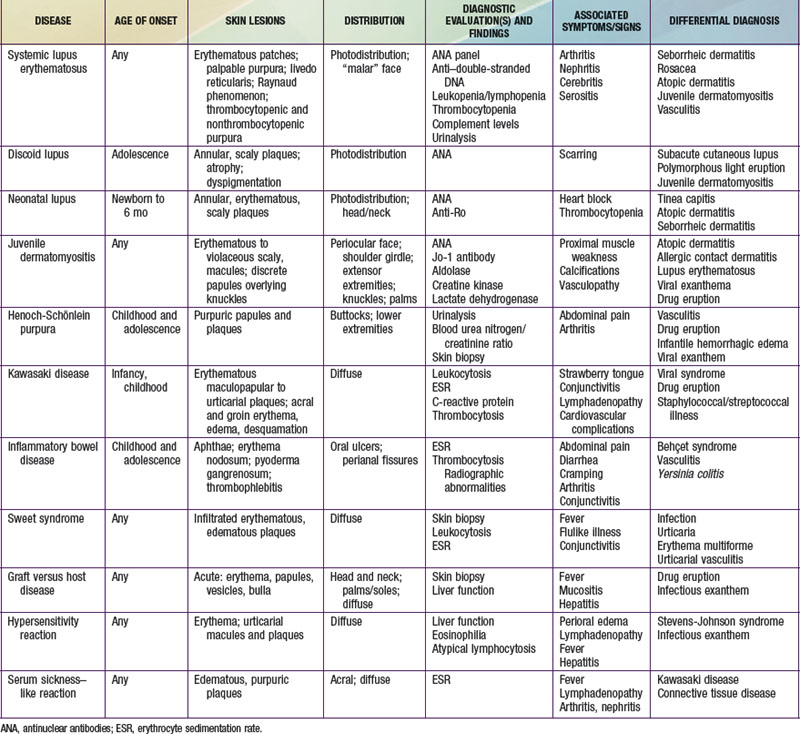

Selected diseases have signature skin findings, often as the presenting signs of illness, that can facilitate the assessment of patients with complex medical status (see Table 637-2 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com).

Connective Tissue Diseases

Lupus Erythematosus

Lupus erythematosus (LE; Chapter 152) is an idiopathic autoimmune inflammatory disease that may be multisystemic or confined to the skin.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic LE (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory multisystem disease. It is a diagnosed when 4 of 11 well-defined criteria are present (Chapter 152). Three of the criteria are skin findings. Criterion 1 is the classic malar or “butterfly” rash (Fig. 637-1). It must be distinguished from other causes of a “red face,” most notably seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and rosacea. Criterion 2 is a discoid rash. Criterion 3 is a photosensitive erythematous macular or papular eruption (Fig. 637-2). Other associated but not diagnostic cutaneous findings include purpuric lesions, livedo reticularis, mucosal ulcerations, Raynaud phenomenon, and nonscarring alopecia.

Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

Neonatal LE (NLE; Chapter 152.1) manifests during the 1st weeks to months of life as annular, erythematous, scaly plaques, typically on the head, neck, and upper trunk (Fig. 637-3). Ultraviolet light may exacerbate or initiate cutaneous lesions. NLE is often misdiagnosed as infantile eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, or tinea corporis. Passive transfer of maternal IgG (anti-Ro/La, SS-A/SS-B) antibodies causes the transient skin lesions; antibody levels wane by 6 mo, generally resulting in clearance of the rash. Congenital heart block occurs in 30% of affected infants, but only 10% of affected infants have both skin and cardiac abnormalities. Noncardiac extracutaneous manifestations, such as anemia, thrombocytopenia, and cholestatic liver disease, are uncommon. Maternal antibody (antinuclear antibody [ANA]) testing is indicated.

Discoid Lupus Erythematosus

Discoid LE (DLE) is uncommon in early childhood and manifests in late adolescence. The signature skin findings in DLE are chronic, erythematous, scaly, atrophic, telangiectatic plaques (Fig. 637-4) on sun-exposed skin that frequently heal with scarring and dyspigmentation. Extracutaneous features may include involvement of the nasal and oral mucosa, eyes, and nails. The differential diagnosis includes other photodermatoses, such as polymorphous light eruption, juvenile springtime eruption, and juvenile dermatomyositis. There is a distinct overlap between SLE and DLE, with common histopathologic features and photoexacerbation; most patients with DLE have normal laboratory results and do not progress to systemic disease. Topical sunscreens and steroids may be helpful. Intralesional steroids and oral antimalarials (hydroxychloroquine) are used for severe disease.

Juvenile Dermatomyositis

Characteristic skin findings are often the presenting sign of juvenile dermatomyositis (JDMS; Chapter 153). An ill-defined, erythematous to violaceous, scaly, minimally pruritic eruption occurs in photodistributed areas such as the face, upper trunk, and extensor extremities. Circumscribed periocular involvement of this heliotrope rash may take the appearance of “raccoon eyes,” particularly in young children. Distinctive papules overlying the knuckles (Gottron papules) are helpful in suggesting the diagnosis in the absence of associated muscle weakness (Fig. 637-5). Other cutaneous features include nail fold and gingival margin telangiectasia, palmar hyperkeratosis (“mechanic’s hands”), and a poikilodermatous (dyspigmentation and telangiectasia) eruption over the shoulder girdle (“shawl sign”). Cutaneous features may precede the systemic illness. The differential diagnosis includes atopic dermatitis, other connective tissue diseases, lichen planus, medication reactions, and infectious exanthems. The paucity of itch in JDMS may help eliminate some diagnostic considerations. Lesional skin demonstrates epidermal atrophy and vacuolar degeneration at the dermal-epidermal junction. JDMS is distinct from adult dermatomyositis in both presentation and prognosis. Pediatric patients have more difficulty with gastrointestinal vasculopathy and cutaneous calcifications but are not at increased risk of malignancy.

Progressive Systemic Sclerosis

Progressive systemic sclerosis frequently manifests as acral (sclerodactyly, ulceration, nail fold telangiectasia, or Raynaud phenomenon) and other cutaneous changes (pinched nose, furrowed perioral skin, or “scleroderma facies”) (Chapter 154). Overlap syndromes, such as CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasias) and mixed connective tissue disease, may include some physical and laboratory features of scleroderma.

Vasculitides

The vasculitides (Chapter 161) encompass a broad group of disorders having considerable overlap with connective tissue diseases. Immune-mediated inflammation of blood vessels of varying size may be caused by an underlying inflammatory state, infection, medication, or malignancy. Common clinical features include palpable nonthrombocytopenic purpuric skin lesions, arthritis, fever, myalgia, fatigue, and weight loss as well as an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Extracutaneous organs that may be involved include the joints, lungs, kidneys, and central nervous system.

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (IgA Vasculitis)

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is a vasculitis that manifests as purpuric lesions prominently on the buttocks and lower extremities of school-aged children (Fig. 637-6). Infantile hemorrhagic edema (IHE; also called acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy) shares some clinical features with HSP but appears in infants and toddlers. IHE is characterized by circumscribed purpuric papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities but, unlike HSP, commonly affects the face and lacks other organ involvement. IHE may follow a recent infection and manifests as peripheral edema and fever; patients with HSP are usually afebrile. HSP must also be differentiated from infectious causes of purpuric skin lesions, such as meningococcemia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and purpuric viral exanthems such as those caused by enteroviruses, as well as from juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and other vasculitides. Diagnosis is confirmed by vasculitis with the immunofluorescence finding of IgA in the blood vessel walls.

Kawasaki Disease

Kawasaki disease (Chapter 160) is a clinical diagnosis based on both cutaneous and extracutaneous features. The skin eruption of Kawasaki disease may be polymorphic, manifesting variously as urticarial, maculopapular, or morbilliform patches and plaques on the trunk and extremities, but early involvement with erythema and peeling in the perineum/inguinal region may be an initial clue to the diagnosis. Acral edema and desquamation are also prominent features but typically occur later. Conjunctivitis (nonpurulent), often with sparing of the limbus, and lingual plaques (“white strawberry tongue”) that shed to produce denuded, erythematous patches with prominent papilla (“strawberry tongue”) are classic mucocutaneous features.

Behçet Disease

Behçet disease (Chapter 155) is multisystem disease that includes oral and genital ulceration and ocular disease (uveitis, relapsing iridocyclitis). Recurrent aphthous stomatitis is present in almost all patients and is commonly the presenting symptom. Genital ulcerations may resemble aphthae, can occur on the penis or scrotum, and may be particularly painful in females. Additional skin findings may include folliculitis, purpuric lesions, erythema nodosum, and pustule formation after venipuncture or skin trauma (pathergy). Differential diagnosis of oral lesions includes recurrent aphthous stomatitis, herpes simplex, and less common oculocutaneous syndromes (e.g., MAGIC [mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage] syndrome). Skin biopsy demonstrates nongranulomatous vasculitis in all vessel sizes. Oral lesions may respond to swish and spit/swallow preparations variably including corticosteroids, antihistamines, antibiotics, and analgesics.

Gastrointestinal Diseases

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Up to 30% of patients with ulcerative colitis (Chapter 328.1) present with cutaneous manifestations. Aphthous ulcers are common and may worsen with gastrointestinal exacerbations. Erythema nodosum, occurring in up to 10% of patients, manifests as warm, erythematous nodules, often on the distal lower extremities. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a focal, ulcerative process that has distinctive, inflamed, undermined borders and a purulent, boggy center. Thrombophlebitis also occurs at an increased rate in patients with ulcerative colitis. In most cases, treatment of the underlying disease state improves the cutaneous sequelae.

Crohn disease, or regional enteritis (Chapter 328.2), classically manifests as perianal fissures and skin tags, abscesses, sinuses, and fistulas; these may be presenting signs. As in ulcerative colitis, aphthae, erythema nodosum, and pyoderma gangrenosum occur at increased frequency and may improve with treatment of the underlying disease. Noncaseating granulomatous inflammation is seen on routine histopathology, and when found in skin not contiguous with the intestinal tract, is labeled metastatic Crohn disease. Metastatic lesions may appear as solitary or multiple, localized plaques or nodules and may be located on perianal, perioral, or other cutaneous surfaces, including scars and ileostomy sites. Standard therapy includes immunosuppressive medications, anti-TNF agents, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, nutritional support, and surgery for complications.

Cutaneous Manifestations of Malignancy

Sweet Syndrome

Also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, Sweet syndrome (Chapter 161.5) manifests abruptly as tender, erythematous, edematous plaques or nodules on any area of the skin, often accompanied by fever, anemia, and leukocytosis. Diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of vasculitis. The differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, erythema multiforme, Behçet disease, and erythema nodosum. The etiology of Sweet syndrome is unknown but may involve a hypersensitivity reaction to a bacterial, viral, or tumor antigen. Forty-two percent of cases of Sweet’s syndrome in childhood occur without an identifiable etiology. The other 58% have been associated with recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, vasculitis with aortitis, recurrent infection due to immunodeficiency, arthritis, SLE, aplastic anemia, Fanconi anemia, and leukemia. Sweet syndrome is sensitive to oral corticosteroids.

Cutaneous Reactions in the Setting of Immunosuppression

Graft versus Host Disease

GVHD (Chapter 131) may have florid cutaneous expression in addition to characteristic extracutaneous features such as fever, mucositis, diarrhea, and hepatitis. It may be either acute or chronic. Acute GVHD occurs in 35-50% of hematopoietic stem cell transplants and may be mistaken for a medication reaction or infectious exanthem, on the basis of the nonspecific erythematous maculopapular eruption that often starts focally and generalizes. Features that may suggest GVHD include timing of eruption (typically 1-3 wk after transplantation, at the time of hematopoietic reconstitution), initial involvement of the head and neck including the ears, and subsequent spread to the trunk, extremities, palms, and soles. Chronic GVHD, which occurs in ≈20% of long-term transplant survivors, is seen most often in patients who have previously experienced acute GVHD. About 50% of patients with acute GVHD eventually have chronic GVHD. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD are distinctive, with sclerotic, dyspigmented scaly plaques and lichenoid papules predominating (Fig. 637-7). Treatment includes systemic immunosuppression supplemented by topical steroids, topical immunomodulators, antihistamines, antipruritics, and emollients. Chronic disease may also respond to pentostatin, mycophenolate mofetil, photochemotherapy (PUVA), UVA-1, and plasmapheresis. GVHD may also develop in susceptible patients who have not undergone transplantation, such as the severely immunosuppressed neonate or infant in response to therapeutic transfusion of nonirradiated blood products, the fetus with congenital immunodeficiency and with transplacental passage of maternal lymphocytes, as well as the older child with malignancy who has received nonirradiated blood products.

Bolanos-Meade J, Vogelsang GB. Chronic graft-versus host disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:1974-1986.

Borlu M, Uksal U, Ferahbas A, et al. Clinical features of Behçet’s disease in children. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:713-716.

Fiore E, Rizzi M, Ragazzi M, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of young children (cockade purpura and edema): a case series and systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:684-695.

Hospach T, von den Driesch P, Dannecker GE. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome) in childhood and adolescence: two new patients and review of the literature on associated diseases. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:1-9.

Jacobsohn DA, Vogelsang GB. Acute graft versus host disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:35.

Lee LA. Transient autoimmunity related to maternal autoantibodies: neonatal lupus. Autoimmune Rev. 2005;4:207-213.

Pluchinotta FR, Schiavo B, Vittadello F, et al. Distinctive clinical features of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus in three different age classes. Lupus. 2007;16:550-555.

Saulsbury FT. Clinical update: Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Lancet. 2007;369:976-978.

Shah KN, Honig PJ, Yan AC. Urticaria multiforme: a case series and review of acute annular urticarial hypersensitivity syndromes in children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1177-e1183.

Timani S, Mutasim DF. Skin manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:265-273.

Van Beek AP, de Haas ER, van Vloten WA, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema: a clinical review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:531-537.

Zulian F, Martini G. Childhood systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:592-597.

637.2 Multisystem Medication Reactions

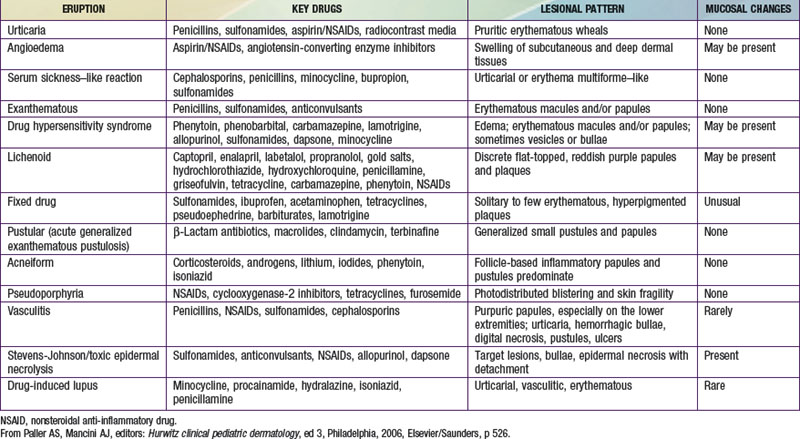

Most cutaneous reactions that result from the use of systemic medications are confined to the skin and resolve without sequelae after discontinuation of the offending agent (see Table 637-3 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com). More severe drug eruptions may be life-threatening, making rapid recognition vital (Chapter 646).

Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (Dress Syndrome)

DRESS syndrome, or drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, was formerly called anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome and pseudolymphoma syndrome. It is classically seen 1-6 wk after initial exposure to an aromatic anticonvulsant or other drugs (allopurinol, minocycline, sulfonamides, other antibiotics) and often manifest as the triad of fever, rash, and hepatitis. The skin rash is characterized by a pruritic, diffuse, erythematous to urticarial eruption of coalescing plaques (Fig. 637-8). Exfoliation early in the course, as seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis, is uncommon. If mucous membrane involvement occurs, it is usually mild. Prominent periocular or facial edema, cervical lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, and malaise accompany this dramatic cutaneous eruption. Eosinophilia (≥ 500/µL) occurs in up to 30% of patients. Atypical lymphocytosis is common. Hepatitis ranging from mild elevation of liver transaminase values to frank hepatic failure may also be accompanied by interstitial nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, shock, and encephalitis. Late-onset (several months) thyroiditis and hypothyroidism may occur as a result of antimicrosomal antibodies directed against thyroid peroxidases involved in drug metabolism. A heritable defect in the epoxide hydrolase pathway, in the case of anticonvulsants, leads to accumulation of toxic metabolites, which react with lymphocytes. Anticonvulsants with the distinctive aromatic structure (carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin) carry a high risk of triggering hypersensitivity syndrome in susceptible individuals and their first-degree relatives. The differential diagnosis includes Stevens-Johnson syndrome, viral exanthem, macrophage activation and hemophagocytic syndromes, and GVHD in the appropriate clinical setting. In addition to anticonvulsants, sulfonamides may cause similar symptoms on 1st exposure because of abnormalities in glutathione S-transferase pathways. Many other antibiotics have also been implicated as causes of this syndrome.

Serum Sickness–Like Reaction

Serum sickness–like reaction (SSLR) manifests as urticarial to purpuric, sharply marginated coalescing plaques and acral erythema/edema, often in association with arthritis, lymphadenopathy, and fever. Unlike with true serum sickness (Chapter 144), laboratory evidence of circulating immune complexes and multisystem involvement of vasculitis are typically absent. The differential diagnosis includes Kawasaki disease, connective tissue diseases, acute annular urticaria, and hypersensitivity syndrome. SSLR is most commonly seen after exposure to cefaclor. The cause is unknown, but a toxic metabolite is suspected. In contrast to hypersensitivity reaction, SSLR typically occurs after repeated drug exposures. Symptomatic treatment and medication withdrawal are recommended.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a pustular lesion, often drug-related (aminopenicillins, macrolides, sulfonamides), that is characterized by many nonfollicular sterile pustules with underlying edema and erythema (Fig. 637-9). Neutrophilia and fever are common, whereas eosinophilia is less common than in DRESS syndrome. The rash may burn or itch; mucous membrane involvement is rare and often mild. Internal organ involvement is not common and often is asymptomatic. Therapy consists of stopping the causative drug; steroids may be needed in some severe cases.

Ben m’rad M, Leclerc-Mercier S, Blanche P, et al. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome: clinical and biologic patterns in 24 patients. Medicine. 2009;88:131-140.

Chen YC, Ching HC, Chu CY. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Arch Dematol. 2010;146(12):1373-1379.

Eshki M, Allamore L, Musette P, et al. Twelve-year analysis of severe cases of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:67-72.

Lerch M, Pichler WJ. The immunological and clinical spectrum of delayed drug-induced exanthems. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:411-419.

Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Nico Bouwes J, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.