Chapter 665 Evaluation of the Child

History

A comprehensive history should include details about the prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal periods. Prenatal history should include maternal health issues: smoking, prenatal vitamins, illicit use of drugs or narcotics, alcohol consumption, diabetes, rubella, and sexually transmitted infections. The child’s prenatal and perinatal history should include information about the length of pregnancy, length of labor, type of labor (induced or spontaneous), presentation of fetus, evidence of any fetal distress at delivery, requirements of oxygen following the delivery, birth length and weight, Apgar score, muscle tone at birth, feeding history, and period of hospitalization. In older infants and young children, evaluation of developmental milestones for posture, locomotion, dexterity, social activities, and speech are important. Specific orthopedic questions should focus on joint, muscular, appendicular, or axial skeleton complaints. Information regarding pain or other symptoms in any of these areas should be appropriately elicited (Table 665-1). The family history can give clues to heritable disorders. It also can forecast expectations of the child’s future development and allow appropriate interventions as necessary.

Table 665-1 CHARACTERIZATION OF PAIN AND PRESENTING SYMPTOM

Physical Examination

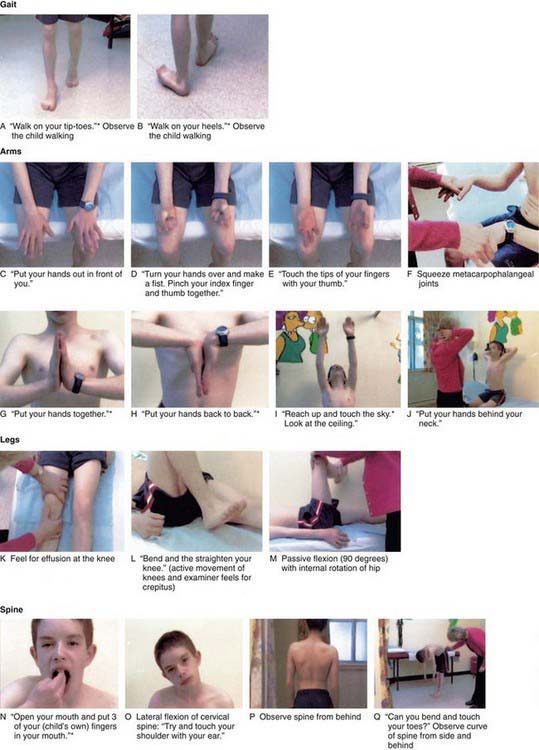

The orthopedic physical examination includes a thorough examination of the musculoskeletal system along with a comprehensive neurologic examination. The musculoskeletal examination includes inspection, palpation, and evaluation of motion, stability, and gait. A basic neurologic examination includes sensory examination, motor function, and reflexes. The orthopedic physical examination requires basic knowledge of anatomy of joint range of motion, alignment, and stability. Many common musculoskeletal disorders can be diagnosed by the history and physical examination alone. One screening tool that has been useful in adults has now been adapted and evaluated for use in children, the pediatric gait, arms, legs, spine (pGALS) test, the components of which are listed in Figure 665-1.

Inspection

Initial examination of the child begins with inspection. The clinician should use the guidelines listed in Table 665-2 during inspection.

Table 665-2 GUIDELINES DURING INSPECTION OF A CHILD WITH MUSCULOSKELETAL PROBLEM

Gait Assessment

Children typically begin walking between 8 and 16 mo of age. Early ambulation is characterized by short stride length, a fast cadence, and slow velocity with a wide-based stance. Gait cycle is a single sequence of functions that starts with heel strike, toe off, swing, and heel strike. The four events describe one gait cycle and include two phases: stance and swing. The stance phase is the period during which the foot is in contact with the ground. The swing phase is the portion of the gait cycle during which a limb is being advanced forward without ground contact (Chapter 664). Normal gait is a symmetric and smooth process. Deviation from the norm indicates potential abnormality and should trigger investigation.

Deviations from normal gait occur in a variety of orthopedic conditions. Disorders that result in muscle weakness (e.g., spina bifida, muscular dystrophy), spasticity (e.g., cerebral palsy), or contractures (e.g., arthrogryposis) lead to abnormalities in gait. Other causes of gait disturbances include limp, pain, torsional variations (in-toeing and out-toeing), toe walking, joint abnormalities, and leg-length discrepancy (Table 665-3).

Limping

Disorders most commonly responsible for an abnormal gait generally vary based on the age of the patient. The differential diagnosis of limping varies based on age group (Table 665-4) or mechanism (Table 665-5). Neurologic disorders, especially spinal cord or peripheral nerve disorders, can also produce limping and difficult walking. Antalgic gait is predominantly a result of trauma, infection, or pathologic fracture. Trendelenburg gait is generally due to congenital, developmental, or muscular disorders. Limping in some cases may also be due to nonskeletal causes such as testicular torsion, inguinal hernia, and appendicitis.

| ANTALGIC | TRENDELENBURG | LEG-LENGTH DISCREPANCY |

|---|---|---|

| TODDLER (1-3 YR) | ||

| Infection | Hip dislocation (DDH) | − |

| Septic arthritis | Neuromuscular disease | |

| Hip | Cerebral palsy | |

| Knee | Poliomyelitis | |

| Osteomyelitis | ||

| Diskitis | ||

| Occult trauma | ||

| Toddler’s fracture | ||

| Neoplasia | ||

| CHILD (4-10 YR) | ||

| Infection | Hip dislocation (DDH) | + |

| Septic arthritis | Neuromuscular disease | |

| Hip | Cerebral palsy | |

| Knee | Poliomyelitis | |

| Osteomyelitis | ||

| Diskitis | ||

| Transient synovitis, hip | ||

| LCPD | ||

| Tarsal coalition | ||

| Rheumatologic disorder | ||

| JRA | ||

| Trauma | ||

| Neoplasia | ||

| ADOLESCENT (11+ YR) | ||

| SCFE | + | |

| Rheumatologic disorder | ||

| JRA | ||

| Trauma: fracture, overuse | ||

| Tarsal coalition | ||

| Neoplasia | ||

From Thompson GH: Gait disturbances. In Kliegman RM, editor: Practical strategies of pediatric diagnosis and therapy, Philadelphia, 1996, WB Saunders, pp 757–778.

DDH, developmental dysplasia of the hip; JRA, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis; LCPD, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease; SCFE, slipped capital femoral epiphysis; −, absent; +, present.

Table 665-5 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF LIMPING

ANTALGIC GAIT

Congenital

Tarsal coalition

Acquired

Trauma

Neoplasia

Infectious

Rheumatologic

TRENDELENBURG

Developmental

Neuromuscular

From Thompson GH: Gait disturbances. In Kliegman RM, editor: Practical strategies of pediatric diagnosis and therapy, Philadelphia, 1996, WB Saunders, pp 757–778.

Back Pain

Children frequently have a specific skeletal pathology as the cause of back pain. The most common causes of back pain in children are trauma, spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and infection (see Table 671-2). Tumor and tumor-like lesions that cause back pain in children are likely to be missed unless a thorough clinical assessment and adequate work-up are performed when required. Nonorthopedic causes of back pain include urinary tract infections, nephrolithiasis, and pneumonia.

Neurologic Evaluation

As the nervous system matures, the developing cerebral cortex normally inhibits rudimentary reflexes that are often present at birth (Chapter 584). Therefore, persistence of these reflexes can indicate neurologic abnormality. The most commonly performed deep tendon reflex tests include biceps, triceps, quadriceps, and gastrocnemius and soleus tendons. Localized or diffuse weakness must be determined and documented. A thorough assessment and grading of muscle strength is mandatory in all cases of neuromuscular disorders.

Radiographic Assessment

Beebe AC, Kerpsack JM. Pediatric musculoskeletal examination. In: Dormans JP, editor. Pediatric orthopedics: core knowledge in orthopedics. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2005:15-35.

Ey EH. Medical imaging of common orthopedic conditions in childhood. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2011;41(1):29-32.

Foster HE, Kay LJ, Friswell M, et al. Musculoskeletal screening examination (pGALS) for school-age children based on the adult GALS screen. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(5):709-716.

Herring JA. Imaging. In: Herring JA, editor. Tachdjian’s pediatric orthopedics. ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:127-168.

Herring JA. The limping child. In: Herring JA, editor. Tachdjian’s pediatric orthopedics. ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:83-94.

Herring JA. The orthopedic examination: a comprehensive overview. In: Herring JA, editor. Tachdjian’s pediatric orthopedics. ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:25-61.

Hosalkar HS, Garg S, Pollack A, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of MRI vs. CT imaging for osteoid osteoma in children. Clin Orthop. 2005;433:171-177.

Hosalkar HS, Moroz L, Drummond DS, et al. Neuromuscular disorders of infancy and childhood and arthrogryposis. In: Dormans JP, editor. Pediatric orthopedics: core knowledge in orthopedics. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2005:454-482.

Jones DHA, Hosalkar HS, Jones S. The orthopaedic management of osteogenesis imperfecta. Curr Orthop. 2002;16:374-388.

Nemeth B. The diagnosis and management of common childhood orthopedic disorders. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2011;41(1):2-28.

Staheli LT. Normative data in pediatric orthopaedics. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16:561-562.

Sutherland DH, Olsten R, Cooper L, et al. The development of gait. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:336-353.