Chapter 116 Evaluation of Suspected Immunodeficiency

Primary care physicians must have a high index of suspicion if defects of the immune system are to be diagnosed early enough that appropriate treatment can be instituted before irreversible damage develops. Diagnosis is difficult because primary immunodeficiency diseases are not screened for at any time during life and most affected do not have abnormal physical features. Screening for SCID (T-cell lymphopenia) has become incorporated as part of the newborn screening programs in a few states. Extensive use of antibiotics may mask the classic presentation of many primary immunodeficiency diseases. Evaluation of immune function should be initiated in those rare infants or children who do have clinical manifestations of a specific immune disorder and in all who have unusual, chronic, or recurrent infections such as (1) 1 or more systemic bacterial infections (sepsis, meningitis); (2) 2 or more serious respiratory or documented bacterial infections (cellulitis, abscesses, draining otitis media, pneumonia, lymphadenitis) within 1 yr; (3) serious infections occurring at unusual sites (liver, brain abscess); (4) infections with unusual pathogens (Pneumocystis jiroveci, Aspergillus, Serratia marcescens, Nocardia, Burkholderia cepacia); and (5) infections with common childhood pathogens but of unusual severity (Table 116-1). Additional clues to immunodeficiency include: failure to thrive with or without chronic diarrhea, persistent infections after receiving live vaccines, and chronic oral or cutaneous moniliasis. Certain clinical features suggestive of immunodeficiency syndromes are noted in Tables 116-2 and 116-3.

Table 116-2 CHARACTERISTIC CLINICAL PATTERNS IN SOME PRIMARY IMMUNODEFICIENCIES

| FEATURES | DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|

| IN NEWBORNS AND YOUNG INFANTS (0 TO 6 MONTHS) | |

| Hypocalcemia, unusual facies and ears, heart disease | DiGeorge anomaly |

| Delayed umbilical cord detachment, leukocytosis, recurrent infections | Leukocyte adhesion defect |

| Persistent thrush, failure to thrive, pneumonia, diarrhea | Severe combined immunodeficiency |

| Bloody stools, draining ears, atopic eczema | Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome |

| Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, neutropenia, recurrent infections | X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome |

| IN INFANCY AND YOUNG CHILDREN (6 MONTHS TO 5 YEARS) | |

| Severe progressive infectious mononucleosis | X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome |

| Recurrent staphylococcal abscesses, staphylococcal pneumonia with pneumatocele formation, coarse facial features, pruritic dermatitis | Hyper-IgE syndrome |

| Persistent thrush, nail dystrophy, endocrinopathies | Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis |

| Short stature, fine hair, severe varicella | Cartilage hair hypoplasia with short-limbed dwarfism |

| Oculocutaneous albinism, recurrent infection | Chédiak-Higashi syndrome |

| Abscesses, suppurative lymphadenopathy, antral outlet obstruction, pneumonia, osteomyelitis | Chronic granulomatous disease |

| IN OLDER CHILDREN (OLDER THAN 5 YEARS) AND ADULTS | |

| Progressive dermatomyositis with chronic enterovirus encephalitis | X-linked agammaglobulinemia |

| Sinopulmonary infections, neurologic deterioration, telangiectasia | Ataxia-telangiectasia |

| Recurrent neisserial meningitis | C6, C7, or C8 deficiency |

| Sinopulmonary infections, splenomegaly, autoimmunity, malabsorption | Common variable immunodeficiency |

Modified from Stiehm ER, Ochs HD, Winkelstein JA: Immunologic disorders in infants and children, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier/Saunders.

Table 116-3 COMMON CLINICAL FEATURES OF IMMUNODEFICIENCY

| Usually present | Recurrent upper respiratory infections |

| Severe bacterial infections | |

| Persistent infections with incomplete or no response to therapy | |

| Paucity of lymph nodes and tonsils | |

| Often present | Persistent sinusitis or mastoiditis (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus, Pneumocystis jiroveci, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas spp.) |

| Recurrent bronchitis or pneumonia | |

| Failure to thrive or growth retardation for infants or children; weight loss for adults | |

| Intermittent fever | |

| Infection with unusual organisms | |

| Skin lesions: rash, seborrhea, pyoderma, necrotic abscesses, alopecia, eczema, telangiectasia | |

| Recalcitrant thrush | |

| Diarrhea and malabsorption | |

| Hearing loss due to chronic otitis | |

| Chronic conjunctivitis | |

| Arthralgia or arthritis | |

| Bronchiectasis | |

| Evidence of autoimmunity, especially autoimmune thrombocytopenia or hemolytic anemia | |

| Hematologic abnormalities: aplastic anemia, hemolytic anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia | |

| History of prior surgery, biopsy | |

| Occasionally present | Lymphadenopathy |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | |

| Severe viral disease (e.g., EBV, CMV, adenovirus, varicella, herpes simplex) | |

| Chronic encephalitis | |

| Recurrent meningitis | |

| Deep infections: cellulitis, osteomyelitis, organ abscesses | |

| Chronic gastrointestinal disease, infections, lymphoid hyperplasia, sprue-like syndrome, atypical inflammatory bowel disease | |

| Autoimmune disease such as autoimmune thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, rheumatologic disease, alopecia, thyroiditis, pernicious anemia | |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | |

| Adverse reaction to vaccines | |

| Delayed umbilical cord detachment | |

| Chronic stomatitis or peritonitis |

EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

Modified from Goldman L, Ausiello D: Cecil textbook of medicine, ed 22, Philadelphia, 2004, Saunders, p 1598.

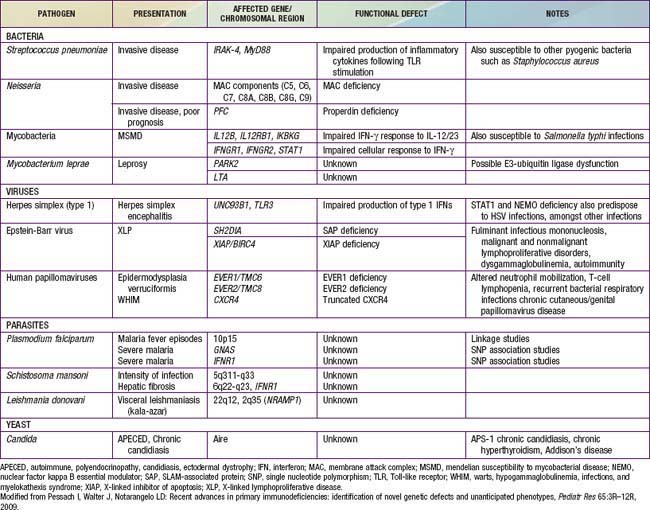

Children with defects in antibody production, phagocytic cells, or complement proteins have recurrent infections with encapsulated bacteria and may grow and develop normally despite their recurring infections, unless they develop bronchiectasis from repeated lower respiratory tract bacterial infections or persistent enteroviral infections of the central nervous system. Patients with only repeated benign viral infections (with the exception of persistent enterovirus infections) are not as likely to have an immunodeficiency. By contrast, patients with deficiencies in T-cell function usually develop opportunistic infections or serious illnesses from common viral agents early in life, and they fail to thrive (Table 116-4).

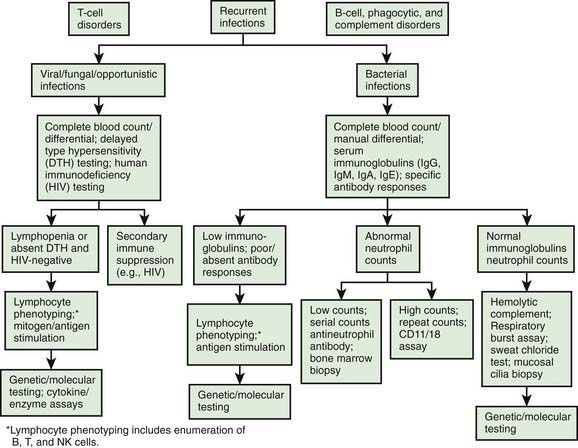

The initial evaluation of immunocompetence includes a thorough history, physical examination, and family history (Table 116-5). Most immunologic defects can be excluded at minimal cost with the proper choice of screening tests, which should be broadly informative, reliable, and cost-effective (Table 116-6 and Fig. 116-1). A complete blood count (CBC), manual differential count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are among the most cost-effective screening tests. If the ESR is normal, chronic bacterial or fungal infection is unlikely. If an infant’s neutrophil count is persistently elevated in the absence of any signs of infection, a leukocyte adhesion deficiency should be suspected. If the absolute neutrophil count is normal, congenital and acquired neutropenias and leukocyte adhesion defects are excluded. If the absolute lymphocyte count is normal, the patient is not likely to have a severe T-cell defect, because T cells normally constitute 70% of circulating lymphocytes and their absence results in striking lymphopenia. Normal lymphocyte counts are higher in infancy and early childhood than later in life (Fig. 116-2). Knowledge of normal values for absolute lymphocyte counts at various ages in infancy and childhood (Chapter 708) is crucial in the detection of T-cell defects. At 9 mo of age, an age when infants affected with severe T-cell immunodeficiency are likely to present, the lower limit of normal is 4,500 lymphocytes/mm3. Absence of Howell-Jolly bodies or pitted erythrocytes by microscopic examination of erythrocytes rules against congenital asplenia. Normal platelet size or count excludes Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. If a CBC and a manual differential were performed on the cord blood of all infants, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) could be detected at birth by the identification of lymphopenia, and lifesaving immunologic reconstitution could then be provided to all affected infants shortly after birth and before they become infected.

Table 116-5 SPECIAL PHYSICAL FEATURES ASSOCIATED WITH IMMUNODEFICIENCY DISORDERS

| CLINICAL FEATURES | DISORDERS |

|---|---|

| DERMATOLOGIC | |

| Eczema | Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, IPEX |

| Sparse and/or hypopigmented hair | Cartilage hair hypoplasia, Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, Griscelli syndrome |

| Ocular telangiectasia | Ataxia-telangiectasia |

| Oculocutaneous albinism | Chédiak-Higashi syndrome |

| Severe dermatitis | Omenn syndrome |

| Recurrent abscesses with pulmonary pneumatoceles | Hyper-IgE syndrome |

| Recurrent organ abscesses, liver and rectum especially | Chronic granulomatous disease |

| Recurrent abscesses or cellulitis | Chronic granulomatous disease, hyper-IgE syndrome, leukocyte adhesion defect |

| Oral ulcers | Chronic granulomatous disease, severe combined immunodeficiency, congenital neutropenia |

| Periodontitis, gingivitis, stomatitis | Neutrophil defects |

| Oral or nail candidiasis | T-cell immune defects, combined defects, mucocutaneous candidiasis, hyper-IgE syndrome |

| Vitiligo | B-cell defects, mucocutaneous candidiasis |

| Alopecia | B-cell defects, mucocutaneous candidiasis |

| Chronic conjunctivitis | B-cell defects |

| EXTREMITIES | |

| Clubbing of the nails | Chronic lung disease due to antibody defects |

| Arthritis | Antibody defects, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, hyper-IgM syndrome |

| ENDOCRINOLOGIC | |

| Hypoparathyroidism | DiGeorge syndrome, mucocutaneous candidiasis |

| Endocrinopathies (autoimmune) | Mucocutaneous candidiasis |

| Growth hormone deficiency | X-linked agammaglobulinemia |

| Gonadal dysgenesis | Mucocutaneous candidiasis |

| HEMATOLOGIC | |

| Hemolytic anemia | B- and T-cell immune defects, ALPS |

| Thrombocytopenia, small platelets | Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome |

| Neutropenia | Hyper-IgM syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrich variant |

| Immune thrombocytopenia | B-cell immune defects, ALPS |

| SKELETAL | |

| Short-limb dwarfism | Short-limb dwarfism with T- and/or B-cell immune defects |

| Bony dysplasia | ADA deficiency, cartilage hair hypoplasia |

ADA, adenosine deaminase deficiency; AID, activation-induced cytidine deaminase; ALPS, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; Ig, immunoglobulin; IPEX, X-linked immune dysfunction enteropathy polyendocrinopathy; SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency.

From Goldman L, Ausiello D: Cecil textbook of medicine, ed 22, Philadelphia, 2004, Saunders, p 1599.

Table 116-6 INITIAL IMMUNOLOGIC TESTING OF THE CHILD WITH RECURRENT INFECTIONS

COMPLETE BLOOD COUNT, MANUAL DIFFERENTIAL, AND ERYTHROCYTE SEDIMENTATION RATE

SCREENING TESTS FOR B-CELL DEFECTS

SCREENING TESTS FOR T-CELL DEFECTS

SCREENING TESTS FOR PHAGOCYTIC CELL DEFECTS

SCREENING TEST FOR COMPLEMENT DEFICIENCY

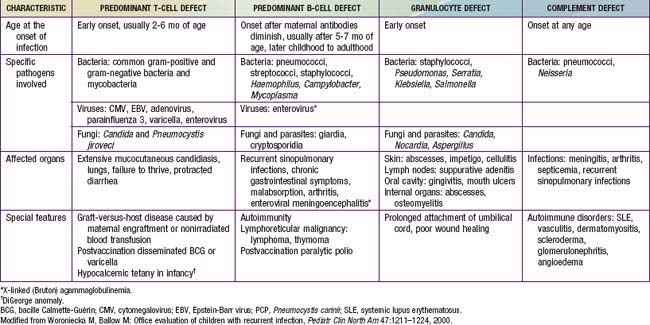

Figure 116-1 A diagnostic testing algorithm for primary immunodeficiency diseases. DTH, delayed type hypersensitivity.

(From Lindegren ML, Kobrynski L, Rasmussen SA: Applying public health strategies to primary immunodeficiency diseases: a potential approach to genetic disorders, MMWR Recomm Rep 53[RR-1]:1–29, 2004.)

Figure 116-2 Absolute lymphocyte counts in normal individual during maturation.

(Data graphed from Altman PL: Blood and other body fluids. Prepared under the auspices of the Committee on Biological Handbooks. Washington, DC, Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 1961.)

Patients found to have abnormalities on any screening tests should be characterized as fully as possible before any type of immunologic treatment is begun, unless there is a life-threatening illness (Table 116-7). Some “abnormalities” may prove to be laboratory artifacts and, conversely, an apparently straightforward diagnosis may prove to be a much more complex disorder. For patients with recurrent or unusual bacterial infections, evaluation of T-cell and phagocytic cell functions is indicated even if results of initial screening tests including the CBC and manual differential, immunoglobulin levels, and CH50 are normal.

Table 116-7 LABORATORY TESTS IN IMMUNODEFICIENCY

| SCREENING TESTS | ADVANCED TESTS | RESEARCH/SPECIAL TESTS |

|---|---|---|

| B-CELL DEFICIENCY | ||

| IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgE levels | B-cell enumeration (CD19 or CD20) | Advanced B-cell phenotyping |

| Isohemagglutinin titers | Biopsies (e.g., lymph nodes) | |

| Ab response to vaccine antigens (e.g., tetanus, diphtheria, pneumococci, Haemophilus influenzae) | Ab responses to boosters or to new vaccines | Ab responses to special antigens (e.g., bacteriophage ϕX174), mutation analysis |

| T-CELL DEFICIENCY | ||

| Lymphocyte count | T-cell subset enumeration (CD3, CD4, CD8) | Advanced flow cytometry |

| Chest x-ray examination for thymic size* | Proliferative responses to mitogens, antigens, allogeneic cells | Enzyme assays (e.g., ADA, PNP) |

| Thymic imaging | ||

| Delayed skin tests (e.g., Candida, tetanus toxoid) | HLA typing | Mutation analysis |

| Chromosome analysis | T-cell activation studies | |

| Apoptosis studies | ||

| Biopsies | ||

| PHAGOCYTIC DEFICIENCY | ||

| WBC count, morphology | Adhesion molecule assays (e.g., CD11b/CD18, selectin ligand) | Mutation analysis |

| Respiratory burst assay | Mutation analysis | Enzyme assays (e.g., MPO, G6PD, NADPH oxidase) |

| COMPLEMENT DEFICIENCY | ||

| CH50 activity | AH50, activity | |

| C3 level | Component assays | |

| C4 level | Activation assays (e.g., C3a, C4a, C4d, C5a) | |

Ab, antibody; ADA, adenosine deaminase; C, complement; CH, hemolytic complement; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; Ig, immunoglobulin; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; PNP, purine nucleoside phosphorylase; WBC, white blood cell; ϕX, phage antigen.

Modified from Stiehm ER, Ochs HD, Winkelstein JA: Immunologic disorders in infants and children, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier/Saunders.

Because of the lack of screening, the true incidence and prevalence of primary immunodeficiency diseases are unknown, although the incidence has been estimated to be 1:10,000 births (Table 116-8). If true, this is higher than some disorders that are part of the newborn metabolic screening program (phenylketonuria [PKU] is 1:16,000) (Chapter 79.1). Approximately 80% of the mutated genes causing the more than 150 known primary immunodeficiency diseases are known, information that is crucial for genetic counseling and that could eventually be used in neonatal screening. Newborn or early childhood screening would be extremely valuable so that timely initiation of appropriate therapy can be initiated before infections develop. Currently it is likely that many affected patients die before a diagnosis is determined.

Table 116-8 2003 MODIFIED IUIS CLASSIFICATION OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY IMMUNODEFICIENCIES

| GROUPS AND DISEASES | INHERITANCE |

|---|---|

| A. PREDOMINANTLY ANTIBODY DEFICIENCIES | |

| XL agammaglobulinemia | XL |

| AR agammaglobulinemia | AR |

| Hyper-IgM syndromes | XL |

| a. XL | XL |

| b. AID defect | AR |

| c. CD40 defect | AR |

| d. UNG defect | AR |

| e. Other AR defects | AR |

| Ig heavy-chain gene deletions | AR |

| κ chain deficiency mutations | AR |

| Selective IgA deficiency | AD |

| Common variable immunodeficiency | AD |

| B. SEVERE COMBINED IMMUNODEFICIENCIES | |

| T−B+NK− SCID | |

| a. X-linked (γc deficiency) | XL |

| b. Autosomal recessive (Jak3 deficiency) | AR |

| T−B+NK+ SCID | |

| a. IL-7 Rα deficiency | AR |

| b. CD3δ, CD3ε, or CD3ζ deficiencies | AR |

| c. CD45 deficiency | AR |

| T−B−NK+ SCID | |

| a. RAG-1/2 deficiency | AR |

| b. Artemis defect | AR |

| Omenn syndrome | |

| a. RAG-1/2 deficiency | AR |

| b. IL-2Rα deficiency | AR |

| c. γc deficiency | XL |

| Combined Immunodeficiencies | |

| a. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase deficiency | AR |

| b CD8 deficiency (ZAP-70 defect) | AR |

| c. MHC class II deficiency | AR |

| d. MHC class I deficiency caused by TAP-1/2 mutations | AR |

| Reticular dysgenesis | AR |

| C. OTHER CELLULAR IMMUNODEFICIENCIES | |

| Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome | XL |

| Ataxia-telangiectasia | AR |

| DiGeorge anomaly | ? |

| D. DEFECTS OF PHAGOCYTIC FUNCTION | |

| Chronic granulomatous disease | |

| a. XL | XL |

| b. AR | AR |

| 1. p22 phox deficiency | |

| 2. p47 phox deficiency | |

| 3. p67 phox deficiency | |

| Leukocyte adhesion defect 1 | AR |

| Leukocyte adhesion defect 2 | AR |

| Neutrophil G6PD deficiency | XL |

| Myeloperoxidase deficiency | AR |

| Secondary granule deficiency | AR |

| Shwachman syndrome | AR |

| Severe congenital neutropenia (Kostmann) | AR |

| Cyclic neutropenia (elastase defect) | AR |

| Leukocyte mycobacterial defects | AR |

| IFN-γR1 or R2 deficiency | AR |

| IFN-γR1 deficiency | AD |

| IL-12Rβ1 deficiency | AR |

| IL-12p40 deficiency | AR |

| STAT1 deficiency | AD |

| E. IMMUNODEFICIENCIES ASSOCIATED WITH LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDERS | |

| Fas deficiency | AD |

| Fas ligand deficiency | |

| FLICE or caspase 8 deficiency | |

| Unknown (caspase 3 deficiency) | |

| F. COMPLEMENT DEFICIENCIES | |

| C1q deficiency | AR |

| C1r deficiency | AR |

| C4 deficiency | AR |

| C2 deficiency | AR |

| C3 deficiency | AR |

| C5 deficiency | AR |

| C6 deficiency | AR |

| C7 deficiency | AR |

| C8α deficiency | AR |

| C8β deficiency | AR |

| C9 deficiency | AR |

| C1 inhibitor | AD |

| Factor I deficiency | AR |

| Factor H deficiency | AR |

| Factor D deficiency | AR |

| Properdin deficiency | XL |

| G. IMMUNODEFICIENCY ASSOCIATED WITH OR SECONDARY TO OTHER DISEASES | |

| Chromosomal Instability or Defective Repair | |

| Bloom syndrome | |

| Fanconi anemia | |

| ICF syndrome | |

| Nijmegen breakage syndrome | |

| Seckel syndrome | |

| Xeroderma pigmentosum | |

| Chromosomal Defects | |

| Down syndrome | |

| Turner syndrome | |

| Chromosome 18 rings and deletions | |

| Skeletal Abnormalities | |

| Short-limbed skeletal dysplasia | |

| Cartilage-hair hypoplasia | |

| Immunodeficiency with Generalized Growth Retardation | |

| Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia | |

| Immunodeficiency with absent thumbs | |

| Dubowitz syndrome | |

| Growth retardation, facial anomalies, and immunodeficiency | |

| Progeria (Hutchinson-Gilford syndrome) | |

| Immunodeficiency with Dermatologic Defects | |

| Partial albinism | |

| Dyskeratosis congenita | |

| Netherton syndrome | |

| Acrodermatitis enteropathica | |

| Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia | |

| Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome | |

| Hereditary Metabolic Defects | |

| Transcobalamin 2 deficiency | |

| Methylmalonic acidemia | |

| Type 1 hereditary orotic aciduria | |

| Biotin-dependent carboxylase deficiency | |

| Mannosidosis | |

| Glycogen storage disease, type 1b | |

| Chédiak-Higashi syndrome | |

| Hypercatabolism of Immunoglobulin | |

| Familial hypercatabolism | |

| Intestinal lymphangiectasia | |

| H. OTHER IMMUNODEFICIENCIES | |

| Hyper-IgE syndrome | AD and AR |

| Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis | |

| Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis with polyendocrinopathy (APECED) | AR |

| Hereditary or congenital hyposplenia or asplenia | |

| Ivemark syndrome | |

| IPEX syndrome | XL |

| Ectodermal dysplasia (NEMO defect) | XL |

AD, autosomal dominant; ADA, adenosine deaminase; AID, activation-induced cytidine deaminase; APECED, autoimmune, polyendocrinopathy, candidiasis, ectodermal dystrophy; AR, autosomal recessive; caspase, cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase; FLICE, Fas-associating protein with death domain–like IL-1–converting enzyme; G6PD, glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase; ICF, immunodeficiency, centromeric instability, facial anomalies; IFN, interferon; Ig, immunoglobulin; IL, interleukin; IPEX, immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; NEMO, nuclear factor B essential modulator; SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency; TAP-2, transporter associated with antigen presentation; XL, X-linked.

Modified from (no authors listed) Primary immunodeficiency diseases. Report of an International Union of Immunological Studies Scientific Committee, Clin Exp Immunol 118:1–28, 1999; Chapel H, Geha R, Rosen F: IUIS PID (Primary Immunodeficiencies) Classification committee: Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update, Clin Exp Immunol 132:9–15, 2003; Stiehm ER, Ochs HD, Winkelstein JA: Immunologic disorders in infants and children, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier/Saunders.

B Cells

Patients found to be agammaglobulinemic should have their blood B cells enumerated by flow cytometry using dye-conjugated monoclonal antibodies to B-cell–specific CD antigens (usually CD19 or CD20). Normally, approximately 8-10% of circulating lymphocytes are B cells. B cells are absent in X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), and present in CVID, IgA deficiency, and hyper-IgM syndromes. This distinction is important, because children with hypogammaglobulinemia from XLA and CVID can have different clinical problems, and the 2 conditions clearly have different inheritance patterns. Patients with XLA have a heightened susceptibility to persistent enteroviral infections, whereas those with CVID have more problems with autoimmune diseases and lymphoid hyperplasia. Specific molecular diagnostic tests for XLA (Chapter 118.1) are necessary in cases without a family history to aid genetic counseling. Molecular testing is also indicated in other B-cell defects.

T Cells

T cells and T-cell subpopulations can be enumerated by flow cytometry using dye-conjugated monoclonal antibodies recognizing CD antigens present on T cells (i.e., CD2, CD3, CD4, and CD8). This is a particularly important test to perform on any infant who is lymphopenic, because CD3+ T cells usually constitute 70% of peripheral lymphocytes. Infants with SCID are unable to produce T cells so are lymphopenic at birth. SCID is a pediatric emergency that can be successfully treated by stem cell marrow transplantation in >94% of cases if diagnosed before serious, untreatable infections develop. Normally, there are roughly twice as many CD4+ (helper) T cells as there are CD8+ (cytotoxic) T cells. Because there are examples of severe immunodeficiency in which phenotypically normal T cells are present, tests of T-cell function are far more informative and cost-effective than enumeration of T-cell subpopulations by flow cytometry. T cells are normally stimulated through their T-cell receptors (TCRs) by antigen present in the groove of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. The TCR can also be stimulated directly with mitogens such as phytohemagglutinin (PHA), concanavalin A (Con A), or pokeweed mitogen (PWM). After 3-5 days of incubation with the mitogen, the proliferation of T cells is measured by the incorporation of radiolabeled thymidine into DNA. Other stimulants that can be used to assess T-cell function in the same type of assay include antigens (Candida, tetanus toxoid) and allogeneic cells (see Table 116-6).

Complement

The most effective screening test for complement defects is a CH50 assay, a bioassay that measures the intactness of the entire complement pathway and yields abnormal results if complement has been consumed from the specimen for any reason. Genetic deficiencies in the complement system are usually characterized by extremely low CH50 values. The most common cause of an abnormal CH50 result, however, is a delay in or improper transport of the specimen to the laboratory. Specific immunoassays for C3 and C4 are commercially available, but further identification of other complement component deficiencies is usually possible only in research laboratories. Nevertheless, it is extremely important to identify which component is missing, because there are different disease susceptibilities depending on whether there are deficiencies of early or late components (Chapter 128). Identifying the mode of inheritance is also important for genetic counseling. Properdin deficiency is X linked, but all of the other complement deficiencies are autosomal. Measurement of C4 can be helpful in assessing suspected hereditary angioedema.

Baker MW, Grossman WJ, Laessig RH, et al. Development of a routine newborn screening protocol for severe combined immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:522-527.

Bustamante J, Zhang SY, von Bernuth H, et al. From infectious diseases to primary immunodeficiencies. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28:235-258. vii

Maródi L, Casanova JL. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: the J project. Lancet. 2009;373:2179-2182.

Mehra A, Sidi P, Doucette J, et al. Subspecialty evaluation of chronically ill hospitalized patients with suspected immune defects. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:143-150.

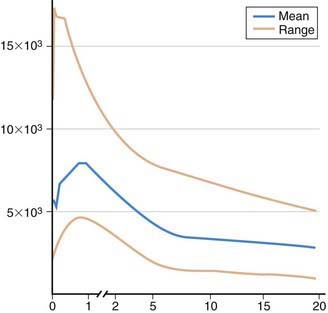

Pessach I, Walter J, Notarangelo LD. Recent advances in primary immunodeficiencies: Identification of novel genetic defects and unanticipated phenotypes. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:3R-12R.

Slatter MA, Gennery AR. Clinical immunology review series: an approach to the patient with recurrent infections in childhood. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152:389-396.