5 Ethics, preoperative considerations, anaesthesia and analgesia

Ethical and legal principles for surgical patients

The level of trust invested in surgeons by patients when they submit to a surgical procedure is unique in society, as is the potential for harm and exploitation. It is paramount therefore that the practice of surgery is subject to ethical and legal principles that enshrine the rights of patients and the duties of surgeons within the context of varying societal expectations. Medical ethics is a complex area, particularly with the challenges that advances in bioethics and new technologies bring, and there should be sufficient latitude within the framework of medical ethics to accommodate differing views in resolving ethical dilemmas. In the United Kingdom, ethical standards are upheld by regulatory bodies such as the General Medical Council and the Surgical Royal Colleges (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 The duties of a doctor registered with the General Medical Council

| Patients must be able to trust doctors with their lives and health. To justify that trust you must show respect for human life and you must: | |

| Make the care of your patient your first concern | |

| Protect and promote the health of patients and the public | |

| Provide a good standard of practice and care | Keep your professional knowledge and skills up-to-date |

| Recognize and work within the limits of your competence | |

| Work with colleagues in the ways that best serve patients’ interests | |

| Treat patients as individuals and respect their dignity | Treat patients politely and considerately |

| Respect patients’ right to confidentiality | |

| Work in partnership with patients | Listen to patients and respond to their concerns and preferences |

| Give patients the information they want or need in a way they can understand | |

| Respect patients’ right to reach decisions with you about their treatment and care | |

| Support patients in caring for themselves to improve and maintain their health | |

| Be honest and open and act with integrity | Act without delay if you have good reason to believe that you or a colleague may be putting patients at risk |

| Never discriminate unfairly against patients or colleagues | |

| Never abuse your patients’ trust in you or the public’s trust in the profession | |

| You are personally accountable for your professional practice and must always be prepared to justify your decisions and actions. | |

Principles in surgical ethics

Principalism

Principalism is a widely adopted approach to medical ethics. Championed by Beauchamp and Childress, it judges all possible actions in a particular ethical dilemma against four principles. These are autonomy, beneficence, non-malfeasance and justice (Summary Box 5.1). Each is considered in more detail below and while addressed separately, it becomes apparent that the principles are linked and do not simply cover four unrelated issues. Protagonists of this approach to bioethics suggest that it provides a practical framework for working through ethical dilemmas, allowing identification of important issues and is universally applicable with its four principles widely acceptable irrespective of culture or religious beliefs. The principles can be applied to most surgical clinical scenarios and if each element is given due consideration it is unlikely that the resulting decision will be unethical.

Informed consent

General considerations

Capacity exists if a patient can:

• understand and retain the information presented

• weigh up the implications, including risk and benefit of the options

Circumstances where the capacity to consent may not exist:

• is suitably trained and qualified

• has sufficient knowledge of the proposed procedure including risks

• understands the process of consent (in the UK as laid out by the GMC).

Consent in specific circumstances

Confidentiality

See Table 5.2 for important sources of information regarding ethics in medicine.

| Publications |

• Human Tissue Act: www.hta.gov.uk/legislationpoliciesandcodesofpractice/codesofpractice.cfm

• Research governance: www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4122427.pdf

• Declaration of Helsinki: www.cirp.org/library/ethics/helsinki/

• Declaration of Geneva: www.cirp.org/library/ethics/geneva/

Specific topics

Ethics committees

Research on human subjects is necessary to advance medical knowledge and treatment. Ensuring that it is carried out in a safe and ethical way is the remit of the ethics committee. The Declaration of Helsinki sets out the principles of ethical research. All clinical trials involving human subjects or tissue must receive ethical approval prior to commencing recruitment. For information on how ethical approval is obtained in the UK see the National Research Ethics Service which is part of the National Patient Safety Agency (http://www.nres.npsa.nhs.uk/). The composition of ethics committees is important and should reflect societal diversity in terms of age, gender, ethnicity and disability and embody a broad range of experience and expertise so that the scientific, clinical and methodological aspects of a research proposal can be reconciled with the welfare of the research participants.

Preoperative assessment

Assessment of operative fitness and perioperative risk

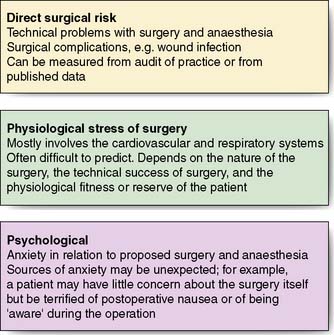

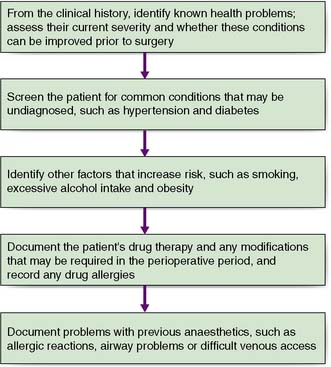

The first priority is to establish the severity and extent of the condition requiring surgery by employing appropriate imaging and other investigations. For example, it is important to know that both recurrent laryngeal nerves are functional prior to thyroid surgery as damage is a recognized complication of this type of operation, on the other hand malignant conditions require appropriate staging to establish the disease extent. The second objective is to identify co-morbid conditions through careful clinical assessment and through optimization, minimize perioperative risk. Figure 5.1 details the areas of potential perioperative risk and Figure 5.2 shows a logical sequence of preoperative assessment. Details of previous operations and anaesthetics should be sought, as well as drug, alcohol and smoking history, specific allergies and concerns. Investigations to assess the surgical condition, co-morbid conditions and general health should be arranged as soon as possible to minimize surgical delay. Thorough and timely preoperative assessment is essential to avoid the expense and delay of cancelled or delayed surgery. Good quality assessment and appropriate optimizations prior to admission mean that many patients can be admitted on the day of surgery.

Systematic preoperative assessment

Smoking

All patients should be offered support to quit smoking, particularly once the decision to operate has been made. The benefits of preoperative smoking cessation are listed in Table 5.3 and should be explained to the patient. Some of the benefits occur within hours (reduced circulating nicotine and carboxyhaemoglobin) while others take weeks, months, or even years. Despite the significant advantages in the perioperative period, many patients are unable or unwilling to stop smoking prior to and after their surgery. Referral to specialist services that support patients to stop smoking may help.

Obesity

Obese patients are at increased risk from surgery and anaesthesia and special equipment may be required. Obese patients are at risk of major associated co-morbidities (e.g. diabetes, obstructive sleep apnoea, degenerative joint disease and cardiovascular disease). Table 5.4 details some of the technical difficulties, perioperative risks and comorbid conditions associated with obesity. If the risks of surgery are outweighed by its potential benefits, surgery may be postponed. In practice, the majority of patients cannot lose weight without support and referral to the GP and dietician for weight loss programmes, including supervised exercise, may be beneficial.

Table 5.4 Significance of obesity in the perioperative period

| Cardiovascular system |

Drug therapy

Pregnancy

Elective surgery should be avoided in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy. The risk of miscarriage and potential teratogenicity is high in the first trimester and this is usually encountered in relation to surgery for an acute abdomen at this stage. Third trimester surgery is associated with significant maternal risks and premature labour (see Table 5.5). If surgery is necessary, it is best undertaken in the second trimester in conjunction with the obstetric team. Surgery in pregnancy is usually an emergency or related to the pregnancy. Early involvement of the anaesthetist is essential as much of the excess risk relates to the general anaesthesia.

Table 5.5 Perioperative risks associated with surgery in pregnant patients

Previous operations and anaesthetics

Summary Box 5.3 Key factors in the anaesthetic history

Preoperative investigations

Haematology

Full blood count

Summary Box 5.4 Preoperative investigation

Haematological full blood count (FBC), coagulation screen, cross match / group and save

Biochemistry urea and electrolytes (U&E), liver function tests (LFTs)

Microbiology Sputum, MRSA screen, virology (patients at high risk of blood borne viruses e.g. HIV)

importance but the platelet and white cell count are also important considerations in terms of haemostatic capacity and where sepsis is suspected. Any patients undergoing surgery with the potential for significant blood loss should have a full blood count, as should those with signs or symptoms of anaemia, patients with significant cardiorespiratory disease that may compromise oxygen delivery to the tissues and those with overt or suspected blood loss (for example gastrointestinal tract symptoms).

Wherever possible, anaemia should be corrected preoperatively to optimize oxygen delivery to the tissues. Preoperative blood transfusion should only be considered for haemoglobin concentrations below 8 g/dl unless the patient is at increased risk of tissue hypoxia due to significant cardiorespiratory disease, especially severe ischaemic heart disease or severe intraoperative bleeding (EBM 5.1). (http://www.transfusionguidelines.org.uk) The threshold for transfusion should be higher (because lower haemoglobin concentrations are tolerated) in patients with chronic anaemia (such as renal failure patients) where compensatory mechanisms such as increased red blood cell 2,3-diphosphoglycerol and reduced blood viscosity increase oxygen delivery.

Coagulation screen

The indications for coagulation studies are shown in Table 5.6 and include suspected abnormal clotting, anti-coagulation treatment and consideration of epidural anaesthesia. When disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is suspected, such as in sepsis, fibrinogen, fibrinogen degradation products (FDP) and D-dimers should be measured. The surgical implications of selected disorders of coagulation are considered below.

Cross matching

Most hospitals have local policies that govern the indications for group and save and cross matching, as well as the number of units required for a given procedure. These policies reflect local resources and availability of blood and blood products in the elective and emergency settings. For rare blood groups and patients with known antibodies, it is important to allow adequate time for cross matching as blood may not be available locally. Blood transfusion and blood products are discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

Biochemistry

Urea and electrolytes

Analysis of urea and electrolytes (U&E) is not necessary in young patients presenting for minor surgery. Elderly patients and those presenting for major surgery, as well as patients with renal dysfunction, cardiovascular disease, fluid balance problems including dehydration and patients on diuretic therapy or any drug therapy that may affect electrolyte balance or renal function should all have routine blood chemistry analysis. Potassium homeostasis is of particular concern as both hypo- and hyperkalaemia can cause arrhythmias. Abnormalities in electrolyte concentrations and renal function should be corrected preoperatively. A detailed discussion of fluid and electrolyte disorders can be found in Chapter 1X.

Cardiac investigations

In general, the involvement of a cardiologist is advisable if anything more than basic cardiac evaluation is required. The significance of common arrhythmias is listed in Table 5.7. The perioperative management of patients with pacemakers is discussed below.

Table 5.7 Significance of common arrhythmias in the perioperative period.

| Arrhythmia | Significance |

|---|---|

| Uncontrolled atrial fibrillation | May compromise cardiac output |

| Exclude metabolic causes, e.g. electrolyte abnormality, and thyrotoxicosis | |

| Ventricular rate should be controlled prior to surgery | |

| Controlled atrial fibrillation | Rarely causes severe perioperative problems unless associated with other significant heart disease |

| Patient may be on anticoagulants; if not, consider thromboprophylaxis | |

| Ventricular extrasystoles | Usually of little significance |

| May indicate ischaemia in patients with ischaemic heart disease | |

| First-degree heart block, asymptomatic bi- or trifascicular block or asymptomatic second-degree heart block | Little significance. |

| Previously considered an indication for temporary pacemaker insertion | |

| Now usually managed by careful monitoring in the perioperative period | |

| Third-degree heart block | Requires pacemaker insertion prior to anaesthesia |

Respiratory investigations

Pulmonary function tests are useful to gauge severity and reversibility of the obstructive component of respiratory disease and may help guide therapy to optimize function. Pulmonary function tests are indicated in pre-existing significant pulmonary disease, patients with significant respiratory symptoms, and in patients undergoing thoracic surgery. Table 5.8 lists the commonly performed pulmonary function tests. Although commonly used, the evidence that preoperative pulmonary function tests are predictive of postoperative complications is not convincing. Indications for preoperative arterial blood gas analysis are given in Table 5.9.

Table 5.8 Respiratory function tests commonly carried out preoperatively

| Respiratory function test | Significance |

|---|---|

| FEV1 | Forced expire volume. Volume of air forcibly expelled in one second |

| FVC | Forced vital capacity. Volume of air forcibly expelled from full inspiration to maximal expiration. |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | Restrictive lung disease (fibrosing alveolitis or scoliosis): the FEV1 and FVC are reduced proportionately with an unchanged FEV1/FVC ratio Obstructive pulmonary disease (asthma and COPD): the FEV1 is reduced by a greater extent than the FVC resulting in a reduced FEV1/FVC ratio A ratio of < 70% indicates obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchodilator therapy is indicated. |

| PEFR | Peak expiratory flow rate. Maximum speed of expiration. PEFR < 70% of expected indicates poorly controlled obstructive lung disease. |

| Gas transfer factor | An estimate of the lungs’ ability to transfer gases. Usually performed by inhaling a gas mixture containing a small amount of carbon monoxide Reduced in conditions that reduce the surface area available for gas transfer (emphysema), conditions that thicken the alveolar membrane (fibrosis), interstitial lung disease, asbestosis and anaemia Increased in polycythaemia (some laboratories adjust for haemoglobin concentration) |

Table 5.9 Indications for blood gas analysis in the preoperative period

| Surgical presentation | Useful features |

|---|---|

| Elective surgery | |

| Chronic respiratory disease: Moderate to severe COPD Fibrotic lung disease Bronchectasis and cystic fibrosis Severe chest wall deformity e.g. ankylosing spondylitis Lung malignancy |

Degree of hypoxaemia (respiratory failure) Distinguish type I (characterized by normocapnia) from type II (characterized by hypercapnia) respiratory failure Detect degree of compensation of hypercapnia (uncompensated, acute hypercapnia results in respiratory acidosis) |

| Emergency surgery | |

| As above. Acute respiratory disease: pneumonia, pleural effusion, ARDS, pneumo- or haemothorax, suspected pulmonary embolism Dyspnoea, decreased SaO2 Shock |

As above Document acid–base disturbance including the presence and degree of metabolic acidosis indicating inadequate tissue perfusion and to guide resuscitation |

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome

The high risk patient

Preoperative MRSA screening

Infection with methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) can have devastating clinical consequences, causing significant in-hospital morbidity and mortality, prolonging hospital stay and increasing cost. Preoperative MRSA screening has been shown to be an effective strategy to decrease MRSA infection rates by identifying asymptomatic carriers and allowing decolonization treatment prior to hospital admission which reduces the risk of transmission and clinical infection (see chapter 4). Preoperative MRSA screening involves swabbing the areas (nostrils, perineum and axillae) regularly colonized by Staphylococcus aureus. MRSA carriers should then undergo preoperative decolonisation using daily antibacterial shampoo, body wash and nasal cream three times daily for five days. Although this regime is only 50–60% effective, in the remainder, reduced bacterial shedding reduces the risk of transmission and infection. Where possible, MRSA positive emergency admissions should be nursed in single room isolation until decolonization is complete.

The preoperative ward round

Summary Box 5.6 Principles of perioperative management

• Optimization of chronic conditions

• Optimization of acute physiological disturbances

• Information sharing / psychological preparation / informed consent

• Surgical strategy / planning / investigations specific to surgical indication.

Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis

In the United Kingdom, 25 000 people die each year from venous thromboembolism (VTE): many of these deaths are preventable (EBM 5.2). A substantial proportion of these are surgical patients. In addition to death from pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT) causes substantial morbidity which may persist to cause the chronic health problems of post-thrombotic syndrome with leg ulceration and swelling with huge health care costs.

‘Each year, it is estimated that 25 000 die from venous thromboembolism in the UK.

Mechanical methods of prevention are effective.

Pharmacological prophylaxis is cost effective.’

NICE Clinical Guideline 92: Venous thromboembolism – Reducing the risk. (2010).

SIGN Clinical Guideline 122: Prevention and management of venous thromboembolism. (2010).

All patients should have their risk of VTE assessed prior to, or on, admission to hospital to enable prophylactic measures to be taken. The patient’s risk of bleeding should be taken into consideration and balanced against the risk of DVT when deciding on thromboprophylaxis. The magnitude of the risk of DVT relates to patient and operative factors as shown in Table 5.10. Measures should be taken to reduce the risk of VTE, in addition to thromboprophylaxis; these include maintaining hydration, encouraging mobility and in patients at very high risk of VTE the use of an inferior vena caval filter. Women should consider stopping oestrogen-containing contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy four weeks prior to surgery.

| Medical patients |

Adapted from: Venous thromboembolism: reducing the risk. NICE clinical guideline 92, 2010.

Mechanical and pharmacological thromboprophylaxis is available (Table 5.11). All surgical patients with increased risk of VTE should be offered mechanical VTE prophylaxis at admission and pharmacological VTE prophylaxis if the risk of bleeding is low. Thromboprophylaxis should be continued until mobility is not significantly reduced, usually for 5–7 days with the exception of orthopaedic lower limb surgery where it should be continued for 2–4 weeks after surgery.

| Mechanical |

| Pharmacological |

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Antibiotic prophylaxis refers to the use of antibiotics peri-operatively to reduce the incidence of surgical site infections (EBM 5.3). Surgical site infections (SSI) refer to infections of the wound, tissues involved in the surgery or devices where surgery involves the insertion of implants or surgical devices (see Chapter 4). Prevention of SSI is important because they are responsible for approximately 16% of hospital acquired infections and cause considerable morbidity, prolonged hospital stay and increased costs. Every surgical patient should be assessed for the risk of SSI and its potential severity and appropriate prophylactic antibiotics selected. The risk of SSI depends on patient and operative risk factors, including the wound class (Table 5.12), SSI risk should be balanced against the risks of antibiotic prophylaxis such as allergy and increasing the prevalence of resistant bacteria and infection with organisms like Clostridium difficile. In general a single dose of intravenous antibiotics is adequate provided the half-life permits activity throughout the operation.

Prophylactic antibiotics should be given intravenously.

Intravenous prophylactic antibiotics should be given ≤ 30 mins before the skin is incised.

The choice of antibiotic should cover the expected pathogens for that operative site.’

SIGN Clinical Guideline 104: Antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery – principles (2008).

| Class | Definition |

|---|---|

| Clean | Operations in which no inflammation is encountered and which do not breach the respiratory, alimentary or genitourinary tracts. Operating theatre technique is continuously aseptic |

| Clean–contaminated | Operations which breach the respiratory, alimentary or genitourinary tracts but without significant spillage |

| Contaminated | Operations where acute inflammation is encountered or where the wound is visibly contaminated, e.g. gross spillage from a hollow viscus or compound injuries less than 4 hours old |

| Dirty | Operations in the presence of pus, a perforated hollow viscus or a compound injury more than 4 hours old |

Preoperative fasting

The purpose of fasting preoperatively is to try to ensure an empty stomach and minimize the risk of regurgitation and aspiration during induction of anaesthesia. Where possible, patients should be starved of food for 6 hours and of clear fluids for 2 hours (EBM 5.4). This may not be possible in the emergency setting in which case anaesthetic technique is adjusted to minimize the risk of aspiration. There are situations where an empty stomach cannot be guaranteed despite fasting. These include pregnancy, gastric outlet or bowel obstruction and any condition that causes a functional gastroparesis (autonomic neuropathy with delayed gastric emptying is common in long-standing diabetes). In such patients a nasogastric tube may be indicated.

‘Water and drinks without milk allowed up to 2 hours prior to induction of anaesthesia.

In children, breast milk allowed up to 4 hours prior to induction of anaesthesia.

Food, including sweets and drinks containing milk up to 6 hours prior to anaesthesia.

Chewing gum not permitted on the day of surgery.

Routine medication continued, can be taken with 30 ml fluid or 0.5 ml/kg in children.’

Perioperative fasting in adults and children, Royal College of Nursing 2005.

Perioperative implications of chronic disease

Some of the more important and common chronic diseases are discussed below.

Cardiovascular disease

Ischaemic heart disease

Ischaemic heart disease is common; increases with age; and significant number of patients with significant coronary artery disease are asymptomatic. Preoperative assessment therefore should focus not only on documented ischaemic heart disease but also on the diagnosis and investigation of occult or undiagnosed disease, especially in high-risk groups (Table 5.13).

Table 5.13 Factors indicating increased risk of ischaemic heart disease

Myocardial infarction

In patients with previous myocardial infarction (MI), the risk of a perioperative MI decreases with time from infarction (Table 5.14), but overall is approximately 6%. This contrasts with patients without a history of MI whose risk is around 0.2%. The mortality of perioperative MI is approximately 50% greater than that of non-perioperative MI. In general, a delay of six months for elective surgery is recommended with three months delay for more urgent surgery, although individual patient factors need to be considered, taking the risks of delayed surgery into account. Post-infarction coronary artery angioplasty, stenting and bypass surgery may reduce the risk of perioperative MI meaning that surgery may be safely carried out sooner. Advice from cardiologists may be helpful in planning the timing of surgery following MI to minimize risk and optimise medical treatment.

Table 5.14 Risk of postoperative myocardial infarction according to time elapsed after previous myocardial infarction.

| Time elapsed after MI | Incidence of postoperative MI (%) |

|---|---|

| > 6 months | 5 |

| 4–6 months | 10–20 |

| < 3 months | 20–30 |

Congestive cardiac failure

The commonest cause of congestive cardiac failure is ischaemic heart disease but the exact cause should be determined where possible as it may influence treatment. Cardiac failure is associated with a number of complications as a result of either poor pump function or underlying cardiac disease (Table 5.15). Uncontrolled heart failure indicated by peripheral oedema, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea or orthopnoea is associated with very high perioperative risk and should be controlled prior to elective surgery.

Table 5.15 Increased perioperative risk in patients with cardiac failure.

| Mechanism | Complication |

|---|---|

| Poor ‘pump function’ | Pulmonary oedema Cardiogenic shock Renal failure Organ ischaemia, e.g. bowel ischaemia Deep venous thrombosis |

| Cardiac disease | Arrhythmias Myocardial infarction Venous thromboembolism |

Valvular heart disease

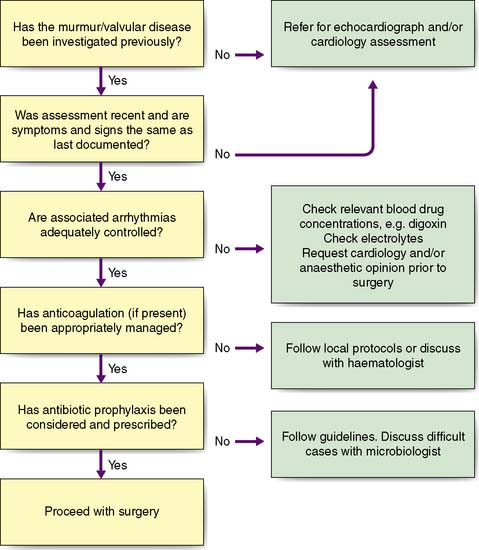

The severity of valvular heart disease should be assessed by clinical evaluation and echocardiography. Associated arrhythmias and cardiac failure should be excluded. An algorithm for the preoperative work-up of these patients in shown in Figure 5.3. Antibiotic prophylaxis guided by local protocol will depend on the risk of bacterial endocarditis according to the surgical procedure and the presence and type (metallic or bioprosthesis) of prosthetic heart valve.

Perioperative management of patients with cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular management

Maximizing myocardial oxygen supply

In order to optimize and monitor myocardial oxygen supply and demand closely, patients with significant cardiovascular and respiratory disease may benefit from invasive perioperative monitoring (Table 5.16 and EBM 5.5).

Table 5.16 Monitors of cardiovascular status during the perioperative period.

| Monitor | Information given |

|---|---|

| Arterial catheter | Continuous measurement of blood pressure |

| Central venous catheter | Central venous pressure (estimate of cardiac preload with important exceptions) |

| Pulmonary artery catheter | Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (a measure of left atrial pressure) and cardiac output (by thermodilution) |

| Oesophageal Doppler | Cardiac output |

Respiratory disease

Diabetes mellitus

Effect of surgical stress on diabetic control

Part of the metabolic response to surgery involves glucose mobilization and lipolysis with increased circulating insulin levels to maintain homeostasis and normoglycaemia. The net result in diabetics is a tendency towards hyperglycaemia and ketoacidosis following surgery, which is exaggerated if complications such as sepsis develop. Glycaemic control should be monitored closely and insulin or oral hypoglycaemic drug doses titrated accordingly. The metabolic response to surgery is discussed in more detail in chapter 1.

Principles of perioperative diabetes management

• whether the diabetes is usually diet, tablet or insulin controlled

• the magnitude of the surgical stress

In practice, many units have protocols for the perioperative management of diabetes, which can be tailored to the individual patient. Table 5.17 gives examples of the typical approach to diabetic control.

Table 5.17 Typical scenarios for diabetic patients presenting for surgery.

| Patient | Procedure | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Diet-controlled diabetic | Elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy (moderate stress response) | Monitor blood glucose until eating |

| Patient on oral hypoglycaemics | Hernia repair (minor stress response) | Omit oral hypoglycaemic on morning of surgery Monitor preoperatively for hypoglycaemia Monitor postoperatively until eating normally Restart oral hypoglycaemics when on normal diet |

| Normally well-controlled | Elective aortofemoral bypass (major stress response) | Omit oral hypoglycaemic on morning of surgery Monitor perioperatively for hypo- or hyperglycaemia If blood glucose > 10 mmol/l, commence glucose/insulin/potassium infusion |

| Normally poorly controlled blood sugar > 10 mmol/l | Emergency aortofemoral bypass (major stress response) | Commence glucose/insulin/potassium infusion prior to surgery Stop oral hypoglycaemics perioperatively |

| Insulin-dependent diabetic | ||

| Well-controlled | Cataract surgery (minor stress response) | Omit morning insulin Monitor blood sugar for hypoglycaemia Restart regular insulin when eating |

| Normally well-controlled | Elective coronary artery bypass graft (major stress response) | Convert to glucose/insulin/dextrose prior to surgery Monitor blood sugar perioperatively Convert to subcutaneous short-acting insulin and then regular insulin as diet reintroduced |

| Blood sugar > 20 mmol/l or ketones in urine | Emergency laparotomy for diverticular abscess (major stress response) | Treat as diabetic ketoacidosis and stabilize prior to surgery Ensure adequate volume resuscitation Continue glucose/insulin/potassium infusion perioperatively Convert to intermittent short-acting and then normal insulin as diet reintroduced |

Methods of insulin administration

For patients with poor glycaemic control or not established on their usual diabetic medication because normal dietary intake has not been established, sliding scale insulin is normally administered. Sliding scale insulin regimens consist of intravenous insulin, glucose and potassium that can be given as a single mixed infusion (the Alberti regimen) (Table 5.18) or as separate infusions of insulin and glucose with potassium. Single mixed infusions are simple, cheap and safer, with less risk of hypoglycaemia, but at the expense of greater flexibility and tight glycaemic control that can be achieved with separate insulin and glucose infusions.

Chronic renal failure

Patients with chronic renal failure are at increased risk of complications in the perioperative period (Table 5.19). Management of fluid balance and specific arrangements for dialysis should be undertaken in conjunction with a nephrologist.

Table 5.19 Risk factors in patients with renal failure undergoing surgery.

| Cardiovascular |

Dialysis dependent patients

Considerations in dialysis dependent patients include:

• Fluid balance. The majority of these patients are anuric and depend on dialysis to remove excess water. Intravenous fluid should be administered with extreme caution.

• Access for dialysis. Patients will either have venous access for haemodialysis (fistulae or large intravenous cannulae) or peritoneal dialysis catheters. Care should be taken to protect this life preserving access. An arterio-venous or dialysis access graft fistula should never be used for intravenous access or phlebotomy.

• Electrolyte imbalance, particularly hyperkalaemia is common. Frequent monitoring should be undertaken.

• Timing of dialysis. This should be decided after liaison with a nephrologist. Preoperative dialysis may be advised to optimize the patient for surgery.

Abnormal coagulation

Patients with abnormal coagulation fall into three categories.

Anticoagulant therapy

Patients receiving oral anticoagulants may require reversal of anticoagulation, bridging anticoagulation to cover the perioperative period and re-anticoagulation. Advice from a haematologist or cardiologist may be helpful. In general, warfarin should be stopped 4–5 days before surgery to achieve an INR < 2 for minor surgery and < 1.5 for major surgery. The risk of thromboembolism during the perioperative period without anticoagulation should be assessed (Table 5.20). Where the risk is high or medium, bridging anticoagulation with intravenous unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin should be administered. Bridging anticoagulation is not required for patients at low risk of thromboembolism. Oral anticoagulation should be reintroduced as soon as the risk of haemorrhage has subsided and the patient is tolerating oral medication. Bridging anticoagulation should only be stopped once the INR is therapeutic.

Table 5.20 Risk stratification of conditions requiring consideration of continuous perioperative anticoagulation

Miscellaneous conditions

There are many other diseases with particular considerations in the perioperative period that are beyond the scope of this chapter for detailed discussion, Table 5.21 gives an overview of some of these.

Table 5.21 Relevance of some medical conditions in the perioperative period.

| Condition | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Neck may be ‘unstable’, careful positioning necessary, complex drug therapy, associated chronic diseases, e.g. renal failure, lung disease |

| Multiple sclerosis | Reduced respiratory reserve; stress of surgery can cause relapse or worsening of disease |

| Epilepsy | Drugs may interact with anaesthetics; surgical stress and some drugs may precipitate seizures |

| Scoliosis or spondylitis | Can significantly reduce respiratory reserve; difficult endotracheal intubation |

| Myasthenia gravis | Risk of respiratory failure or aspiration; anaesthetic technique needs modifying |

| Sickle-cell anaemia | Stress of surgery, hypoxia, hypothermia can all precipitate sickle-cell crisis |

Anaesthesia and the operation

Local anaesthetic agents

Maximum local anaesthetic doses are shown in Table 5.22. A patient receiving large doses of local anaesthetic should be monitored with ECG, pulse oximetry and non-invasive blood pressure measurement. Local anaesthetic toxicity as a result of inadvertent injection into the blood stream or overdose may be heralded by perioral tingling and can result in arrhythmias and convulsions (Table 5.23). Intravascular injection should be avoided by aspirating on the needle prior to injection. Treatment of toxicity is supportive; the airway should be secured, ensuring adequate ventilation and the circulation supported with intravenous fluid and antiarrhythmics if necessary. Seizures should be controlled with small increments of intravenous benzodiazepines.

Table 5.22 Safe maximum doses of commonly used local anaesthetics

| Drug | With adrenaline (epinephrine) (mg/kg) | Without adrenaline (epinephrine) (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Lidocaine | 6 | 2 |

| Bupivacaine | 2 | 2 |

| Prilocaine | Maximum 600 mg |

Table 5.23 Signs of local anaesthetic toxicity

| Early |

Spinal and epidural anaesthesia

Spinal anaesthesia

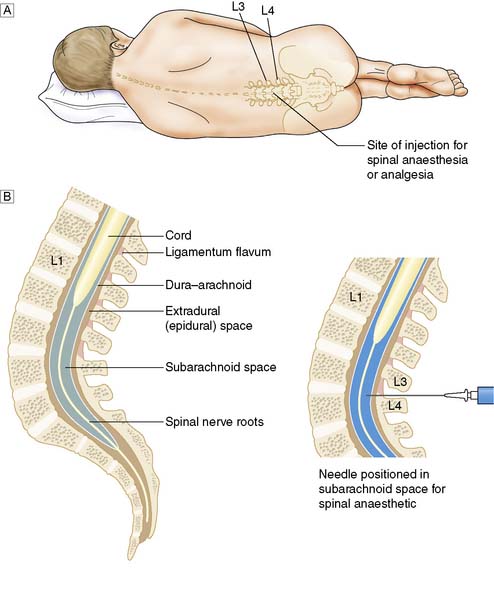

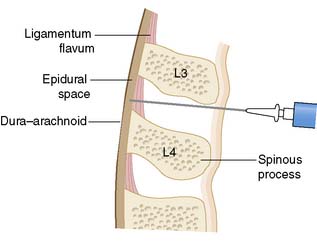

Spinal anaesthetic is defined by the introduction of local anaesthetic, usually lidocaine or bupivacaine into the subarachnoid space to block the spinal nerves before they exit the intervertebral foramina (Fig. 5.4). To protect against damage to the spinal cord, spinal anaesthesia is administered below L2, either at the L3/4 or L4/5 level. At this level, the cauda equina nerves acquire their perineural coverings and myelin sheath as they exit the dura making them exquisitely sensitive to the effect of local anaesthetic. As a result, 2–4 ml of local anaesthetic produces a dense block up to T6 level, with a rapid onset of action, giving 2–3 hours of surgical anaesthesia. The addition of 6–8% glucose increases the density of the spinal anaesthetic solution making it easier to control the level of the block using gravity. Aspiration of subarachnoid fluid confirms the correct site of the spinal needle.

Epidural anaesthesia

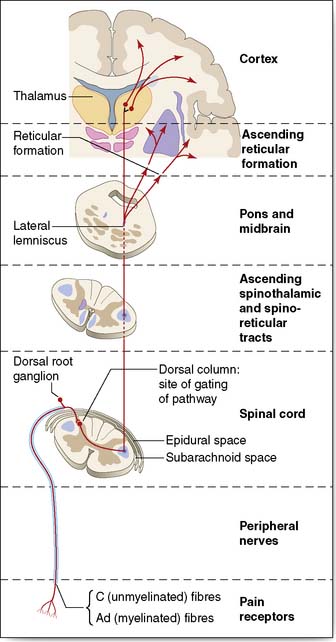

Epidural anaesthesia involves the injection of local anaesthetic into the epidural space which extends along the entire vertebral canal between the ligamentum flavum and dura mater (Fig. 5.5). Local anaesthetic spreads cranio-caudally penetrating the meningeal sheaths containing the nerve roots causing an anaesthetic block affecting several dermatomes. The level of epidural anaesthetic is therefore dictated by the proposed site of surgery and the dematomes involved. The nerve roots are fully covered and myelinated as they traverse the epidural space and therefore a larger volume (10–20 ml) of local anaesthetic, compared to spinal anaesthesia, is required to achieve anaesthesia. The technique by which a needle is introduced into the epidural space depends on sensing a loss of resistance as the needle passes through the ligamentum flavum; aspiration ensures that the needle is not advanced too far into the subarachnoid space, termed a ‘dural tap’. An ongoing CSF leak following a dural tap can lead to loss of CSF volume and headache. As well as adequate hydration, the CSF leak may be managed by the use of a blood patch. This involves using the patient’s own blood injected into the epidural space to seal the leak. If a dural tap goes undetected with the injection of local anaesthetic into the subarachnoid space, a profound block of all spinal nerves will result, with the potential of respiratory arrest and profound hypotension. A catheter is often left in the epidural space to provide access for ongoing analgesia. Table 5.24 details some common complications of epidural anaesthesia. Both spinal and epidural anaesthesia block spinal cord sympathetic outflow. Rapid vasomotor paralysis with peripheral vasodilatation is an early sign of a successful spinal or epidural anaesthetic due to the rapid onset of blockade in these small unmyelinated fibres. Conversely, the resulting peripheral vasodilatation can be a nuisance with unwanted hypotension requiring treatment with intravenous fluids, vasoconstrictors, or reduction in the rate of the epidural infusion.

Table 5.24 Complications of epidural anaesthesia and analgesia

| Complication | Steps to avoid complication |

|---|---|

| Epidural abscess (0.015–0.05%) | Avoid if skin or systemic sepsis |

| Epidural haematoma (0.01%) | Correct coagulopathy, reverse anticoagulation and avoid in patients who have received recent heparin |

| Respiratory depression | Avoid high epidural block, (C3–5 innervate diaphragm) |

| Cardiac depression | Avoid mid-thoracic epidural, blocking cardiac sympathetic outflow. The loss of positive chrontropic and inotropic innervation results in cardiovascular instability and hypotension |

Peripheral nerve block

Peripheral nerve blockade requires a detailed working knowledge of the target nerve’s surface anatomy, adjacent structures, as well as the cutaneous area supplied by it. Use of a nerve stimulator and insulated block needle can improve the accuracy of placement of the nerve block catheter. A list of commonly performed nerve blocks and their indications are detailed in Table 5.25.

| Block | Indication |

|---|---|

| Axillary or supraclavicular | Upper limb surgery |

| Interscalene | Shoulder and upper limb |

| Femoral | Lower limb surgery |

| Sciatic | Lower limb surgery |

| Intercostal nerves | Thoracotomy, fractured ribs |

| Ilio-inguinal/iliohypogastric | Inguinal hernia |

| Penile | Circumcision |

Postoperative analgesia

Good postoperative analgesia is essential in ensuring surgical success by minimizing psychological and physiological morbidity, enabling early mobilization and optimizing respiratory function. Despite this, approximately 20% of postoperative patients will have inadequate analgesia. Successful postoperative analgesia requires preoperative planning, taking into account the nature of the proposed surgery, patient factors and preferences and their comorbidity. Knowledge of pain physiology, assessment, analgesic drugs, including routes of delivery and pharmacology is essential. The pain pathway is illustrated in Figure 5.6. Many hospitals have acute pain teams involving doctors and specialist nurses to deliver improved patient analgesia.