24 Ethical Issues in Pediatric Critical Care

Pearls

• The practice of medical ethics seeks to identify and resolve competing moral claims among patients, their families, healthcare professionals, healthcare institutions, and society at large.

• Appeals to rights, such as the right of conscience, might not resolve a dispute.

• Legal considerations provide a general framework for decision making, but rarely provide a definitive answer to complex ethical questions. The law typically represents the floor, not the ceiling, of standards of morality.

• The creation of an ethical working environment in the pediatric critical care unit is a necessary precondition for addressing ethical issues raised by specific patient situations.

• The primary focus in decision making should be the interests of the child.

• Care for the critically ill child must be centered on the family.

• Informed consent is a process, not an event, and it has four key requirements: competency, disclosure, understanding, and voluntariness.

• Minors may be legally empowered to make their own decisions if they are deemed emancipated by state law or determined to be a mature minor by a judge.

• Pediatric critical care professionals should refrain from speaking about withdrawal of care. Although treatments may be withdrawn, care is never withdrawn. Care can be redirected from a focus on cure to a focus on comfort.

• The satisfaction of the patient, family, and provider may all be endangered when information is poorly delivered.

• Any medical treatment, including nutrition and hydration, can be withheld or withdrawn.

Defining medical ethics

Medical ethics is the discipline devoted to the identification, analysis, and resolution of value-based problems that arise in the care of patients.29 The discipline is unique only because it relates to the particular dilemmas that arise in medicine, not because it embodies or appeals to some special moral principles or methodology. The practice of medical ethics seeks to identify and resolve competing moral claims among patients, their families, healthcare professionals, healthcare institutions, and society at large.

Sources of Moral Guidance

Everyone draws on multiple sources of moral guidance, including parental and family values, cultural traditions, and religious beliefs. These sources are the roots of moral values, and they create a disposition to do the right thing. However, for many reasons these values and beliefs do not provide sufficient guidance for addressing dilemmas in clinical ethics.50

Occasionally, individuals may explain their actions as a matter of conscience: to act otherwise would make them feel guilty or ashamed or violate their sense of wholeness or integrity. Conscience involves self-reflection and judgment about whether an action is right or wrong.9 Conscience thus arises from a fundamental commitment or intention to be moral. It unites the cognitive, conative, and emotional aspect of the moral life by a commitment to integrity or moral wholeness.80 It is a commitment to uphold one’s deepest self-identifying moral beliefs; a commitment to discern the moral features of a particular case as best one can, and to reason morally to the best of one’s ability; a commitment to emotional balance in one’s moral decision-making; and a commitment to make decisions according to one’s moral ability and to act upon what one discerns to be the morally right course of action.80

Individuals often appeal to rights, such as a right to healthcare, to explain positions on ethical issues. To philosophers, rights are justified claims that a person can make on others or on society.9 The language of rights is widespread, but an appeal to rights is often controversial. Other people might deny that the right exists or assert conflicting rights. Claims of rights are often used to end debates; however, the crucial issue is whether persuasive arguments support the existence of the right.50

It is a mistake to suppose that moral principles simply prescribe what to do or require uniform action and conformity. First, because they are stated abstractly, they must be interpreted or specified35; this is done by making practical moral judgments, leaving considerable room for interpretation and disagreement from person to person or from culture to culture, even among those who agree on the importance of these principles. Second, because principles can conflict in a given situation, they sometimes have to be ranked, and people can reasonably disagree about how to do this justifiably.

Clinical ethics as an aid to nursing care

Learning about clinical ethics can help nurses identify, understand, and resolve common ethical issues in pediatric critical care. By studying published cases, healthcare workers can gain experience in resolving specific dilemmas.35,50 By studying cases that illustrate common ethical problems, nurses can better recognize the ethical issues they encounter. On many issues, healthcare professionals, philosophers, and the courts agree on what should be done. Clinical ethics can help to identify actions that are clearly right or wrong and those that are controversial. Subsequent sections of this chapter and information in the Chapter 24 Supplement on the Evolve Website will highlight areas of ethical agreement as well as those areas of ongoing controversy.

A systematic approach to ethical dilemmas helps to identify important considerations and fosters consistency in decisions. Clinical ethics is a practical discipline that provides a structural approach to decision making that can assist the healthcare team in identifying, analyzing, and resolving ethical issues in clinical practice.35 Box 24-1 lists key steps to take when approaching an ethical dilemma that needs to be clarified, analyzed, and resolved.

Box 24-1 Approach to Ethical Dilemmas

• Identify and define the problem. Determine whether there are different ways to view the problem.

• Identify potential consequences of the different options.

• Determine the policies, laws, rights, duties or values that are important. If there is conflict, which carries the most moral weight?

• Negotiate for a solution to the problem. What are the weaknesses of the solution? Is the solution consistent and universal?

Creating an environment that supports ethical practice

On a daily basis nurses, physicians, and other members of the pediatric critical care healthcare team are faced with maintaining the delicate balance between the application of complex technological care and humane, ethical care for the critically ill pediatric patient.74 Ethical considerations in the pediatric critical care unit often involve moments of crisis marked by disagreement over decisions, such as whether to resuscitate a patient; to withhold or withdraw “futile” treatment over a patient’s or family’s objections; or to allocate limited or expensive resources, such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or the last pediatric critical care unit bed.

The expansion of technology combined with awareness of biologic, economic, and ethical limits to applying that technology can lead to uncertainty and conflict when it appears that providers are unable to restore a patient to the patient’s previous state.59 To address these complex issues, the pediatric critical care unit team must recognize and address the ethical issues that exist each and every day in interactions with families, patients, and fellow workers. The creation of an ethical working environment in the pediatric critical care unit is a necessary precondition for addressing ethical issues involved in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, the limitation or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, and conflicts in medical decision making.

The American Association of Critical Care Nurses has recognized the inextricable links among quality of the work environment, excellent nursing practice, and patient care outcomes. The American Association of Critical Care Nurses is also committed to creating work and care environments that are safe, healing, humane, and respectful of the rights, responsibilities, needs, and contributions of all people, including patients, their families, and nurses. Six standards for establishing and sustaining healthy work environments have been identified (Box 24-2).5

Box 24-2 Key Elements for Establishing and Sustaining Healthy Work Environments

• Skilled Communication—Nurses must be as proficient in communication skills as they are in clinical skills.

• True Collaboration—Nurses must be relentless in pursuing and fostering true collaboration.

• Effective Decision Making—Nurses must be valued and committed partners in making policy, directing and evaluating clinical care, and leading organizational operations.

• Appropriate Staffing—Staffing must ensure the effective match between patient needs and nurse competencies.

• Meaningful Recognition—Nurses must be recognized and must recognize others for the value each brings to the work of the organization.

• Authentic Leadership—Nurse leaders must fully embrace the imperative of a healthy work environment, authentically live it and engage others in its achievement.

From American Association of Critical Care Nurses: AACN standards for establishing and sustaining healthy work environments: a journey to excellence. Am J Crit Care 14:187-197, 2005.

A frequent ethical problem in the acute care setting is a difference of opinion among the healthcare team and often involves disputes between and a nurse and a physician.27,59,74 Such conflicts typically involve a nurse disagreeing with a physician concerning ethical issues such as the extent or invasiveness of treatment, when to stop treatment, and when not to attempt resuscitation in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest. In order to create an environment that supports ethical practice, a shift from a chain-of-command relationship to interdisciplinary care is required. An interdisciplinary approach seeks to blur professional boundaries and requires trust, tolerance, and a willingness to share responsibility.74 The challenge in the pediatric critical care unit is to develop and sustain organizational and structural changes that reflect an ethical practice environment, making routine the collaborative and communicative strategies that ethical issues often require.

How are ethical issues in pediatrics different?

Children Are Different

Children are smaller than adults. This fact is obvious, but the practical and ethical implications are substantial. “The child’s small size can contribute to the child’s feeling intimidated by adults, even if unintentionally. Adults must physically look down at children, and children unavoidably must look up at adults. The world is largely designed for adults; so although adults sit down, children must climb up. These simple physical facts both establish and illustrate the relative imbalance of power, influence, and authority between children and adults.”10

Healthcare professionals are ethically compelled to respect and integrate the child’s expressed wishes, the parents’ expressed outcomes, the child’s maturational needs, and the family’s cultured beliefs about family roles and child-rearing practices. Such considerations bring new ethical considerations and challenges to treatment (Box 24-3).

Box 24-3 Caring for Children: Core Ethical Issues

• Children are inherently more vulnerable than adults.

• Children’s abilities are more variable and change over time.

• Children are more reliant on others and their environment.

• Ethical principles and practices in the treatment of adults must be modified in response to the child’s current developmental abilities and legal status.

• Healthcare professionals must develop skills to work with families, agencies, and systems.

• Healthcare professionals must maintain an absolute commitment to the safety and well-being of the child.

• Although young children are not autonomous, their potential autonomy deserves respect.

• The primary focus in decision making should be the interests of the child.

• Healthcare professionals must constantly monitor one’s own actions and motivations.

• Healthcare professionals must seek consultation and advice in difficult situations.

• Children should be given the protection of privacy.

• All persons with decisional capacity, regardless of age, have the right to make healthcare treatment decisions.

Modified from: Belitz J, Baley RA: Clinical ethics for the treatment of children and adolescents: a guide for general psychiatrists. Psychiatr Clin N Am 32:243–257, 2009.

Because children cannot weigh risks and benefits, compare alternatives, or appreciate the long-term consequences of decisions, they are incapable of making informed decisions. As a result, autonomy is less important in pediatrics than in adult medicine. A child’s objections to beneficial medical interventions do not have the same ethical force as an adult’s informed refusals. Because children are immature and vulnerable, they need an adult to make decisions for them and to protect their best interests. Parents are presumed to be the appropriate decision makers.2

As children mature, they become capable of making informed decisions, and their involvement in care should increase. Pediatric critical care unit professionals need to provide the child with information about his or her condition and opportunities to participate in decisions about healthcare, to the extent that it is developmentally appropriate.2

Children also differ from one another. In a very real way, there is no such category as “children.”10 Infants differ from toddlers, who differ from preschoolers, who differ from school-aged children and adolescents. Furthermore, within any group of children there is wide variability in size, ability, psychosocial development, cognitive development, and maturity. Many children develop inconsistently in physical, cognitive, emotional, social, and moral abilities and characteristics. The individual child may progress and regress in the face of various challenges and traumas, being “childish” one day and a “young lady” or “young man” the next. Children manifest much broader developmental and individual variability than do adults. Consequently, pediatric critical care unit professionals must tailor their approaches and care to the individual state and abilities of each pediatric patient. The child’s ability to engage in particular aspects of care, including its ethical aspects, or to move toward particular goals of treatment can vary with the child’s immediate developmental abilities, themes, challenges, and tasks.10

The Family Is the Patient

Care for the critically ill child must be family-centered.76 Family-centered care is an approach to healthcare that shapes healthcare policies, programs, facility design, and day-to-day interactions among patients, families, physicians, and other healthcare professionals. Healthcare professionals who practice family-centered care recognize the vital role that families play in ensuring the health and well-being of children and family members of all ages. These practitioners acknowledge that emotional, social, and developmental support are integral components of healthcare. They respect each child’s and family’s innate strengths and view the healthcare experience as an opportunity to build on these strengths, and the providers support families in their caregiving and decision-making roles. Family-centered approaches lead to better health outcomes and wiser allocation of resources as well as greater patient and family satisfaction.4

Given that the family is the child’s primary source of strength and that the family’s perspectives are important in clinical decision making, the pediatric critical care unit team has a moral obligation to the patient’s family and a duty to increase family access to the pediatric critical care unit. Increased access to the pediatric critical care unit has also resulted in more reports of parental presence during bedside pediatric critical care unit rounds, complex procedures, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.16,23,63,68 All patient care units should develop written documentation for presenting the option of family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and invasive procedures. Education programs should be developed for healthcare staff to include: the benefits of the family’s presence for the patient and the family, criteria for assessing the family, the role of the professional assigned as the family support person, family support methods, and contraindications for family presence.

Medical decision making

Consent or Permission from Parents or Guardians

“Parents or guardians usually have the authority to give consent or permission for their child’s healthcare and participation in research. Reasons for this social policy include, first, that parents in general have the greatest knowledge about, and interest in, the well-being of their own minor children.”40 Another well-recognized reason that parents have legal authority to make these and many other decisions for their minor children is that parents or guardians must address the consequences of the choices being made. Clinicians should generally try to respect the parents’ preferences because of the importance parents play in fostering the child’s well-being and shaping the child’s values.40

The person who gives consent must have the capacity to make decisions. The terms competent and incompetent are often reserved for legal contexts. Courts can make a determination about whether someone is competent. The presumption is that adults are legally competent and minors are not. Minors—in most parts of the United States this includes those younger than 18 years—are regarded as incompetent to make decisions about their own healthcare, especially if the decisions are momentous.40 The reality is that many adults lack decision-making capacity, but have not been declared legally incompetent in the courts, and many legally incompetent minors have good decision-making capacity. Thus, the legal notion of competence and that of decision-making capacity should be distinguished.40

For the purposes of healthcare, the term decision-making capacity refers to an individual’s ability to understand information needed to make informed consent, evaluate this information in terms of stable personal values, and use and manipulate the information in a reasonable manner.40 For important decisions, clinicians should assess how well those giving the consent can understand the information, deliberate, and make and defend choices. It also is important that those giving consent communicate choices appropriately. These details should help clinicians decide whether parents or older minors have the capacity to make important healthcare decisions.

Informed consent or permission should have the following elements40:

1. All information or material important to the decision has been disclosed.

2. Those giving consent comprehend or understand the information that has been disclosed.

3. Those giving consent voluntarily agree to participate.

4. Those giving consent are competent to make a decision to participate.

5. Those giving consent agree to the procedure, act, intervention, or research.

Parents giving consent or permission should be guided by what is in the best interest of their child. Their decisions can be challenged, for example, if they endanger the child. The best interest of the child standard is one of four important standards for medical decision making; the other three are self-determination, advance directive, and presumed consent.40 Although the best interest of the child standard is of special importance in pediatrics, each of the four standards has a role in making healthcare decisions for minors.

Assent and Self-determination

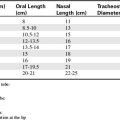

Self-determination, as a standard for healthcare decision making, applies to competent adults and to many older or emancipated minors (Table 24-1). This standard of self-determination presupposes that the person is autonomous or capable of self-determination, has informed understanding, and makes the choices voluntarily. The standard honors the basic moral principles mentioned previously; it flows from the moral principle of autonomy or self-determination and honors individual liberty; and it enables people to make choices about themselves, assess their own best interest, and develop their own capacities and life plans as they wish, as long as they do not harm others.40

Table 24-1 Glossary of Terms Related to Adolescent Medical Care

| Term | Definition |

| Assent | To give clear agreement, used in connection with a child’s or adolescent’s agreement to treatment or research participation when consent is not possible because the individual has not yet achieved adult status (see Consent below, which in its narrow sense can be given only by competent adults) |

| Bright line | Clear distinction that solves a matter in dispute in law |

| Capacity | Individual’s ability to understand facts and consequences of a decision, communicate a choice, and appreciate the effects of that choice and alternatives; a status that is in flux and evolving in adolescents; a clinical determination that is context-sensitive |

| Competency | Ability to understand facts and consequences; in law, related to definitive criteria (e.g., age of majority, after which legal adulthood is attained, with the presumption of competence) |

| Consent | Voluntary agreement freely made without coercion or duress, and with adequate knowledge (informed); as strictly construed, can be given only by a competent adult, or in certain limited circumstances, by emancipated or mature minors; grounded in ethical principle of respect for autonomy and patient self-determination |

| Emancipation | Condition by which a minor is recognized as an adult for legal purposes; often triggered by certain events (e.g., marriage, military service, childbearing) or under certain conditions (e.g., adolescent living alone and financially supporting self) |

| Ethical | Addresses what a clinician should or should not do based on moral guiding principles; not limited to legal mandate, although often tied to certain legal rules and professional codes |

| Legal | Addresses what a clinician can or cannot do based on state, federal, and local laws and regulations (required; legal sanctions may follow a breach) |

| Mature minor | Consent authority related to context-sensitive and specific situations, or conditions in which an adolescent demonstrates a mature capacity to make decisions related to healthcare |

Modified from Campbell AT: Consent, competence and confidentiality related to psychiatric conditions in adolescent medicine practice. Adolesc Med 17: 25-47, 2006.

Although the law grants full competence on the occasion of a specific birthday (e.g., 18 years of age), this practical and useful legal practice fits poorly with medical decision making. In medicine, it is more useful to view capacity as a matter of degree, and less like the “light-switch” concept found in the law.40 In both law and medicine, young children are the paradigm of persons unable to make decisions for themselves. Infants are among the many incompetent and vulnerable, but minors just before the age of majority are as competent as many adults. Most young children lack the capacity, maturity, experience, or foresight to make important decisions for themselves and to determine which decisions promote their well-being and opportunities. As children gain maturity, many seek to understand important healthcare decisions being made for them, and older children may have strong opinions about their care.12,25,82,85,87

To acknowledge the child’s emerging capacities and point of view, and to promote the child’s well-being, clinicians seek the child’s assent in addition to parental permission when possible.2,40 Healthcare providers may seek the assent or agreement of children as young as 7 years. As minors become increasingly mature and competent, they should be accorded more self-determination. Children with life-threatening or chronic illnesses, for example, may want to participate in discussions and decisions about their care and find that it is a way to gain control and respect.82 Ignoring their desires to participate can cause pain, isolation, misunderstanding, and frustration.

Assent is different from consent, because the minor’s preferences need not be honored in the same way as those of adults.40 Whether a minor’s preference should be honored can depend on the probability and magnitude of the harms involved and the irreversibility of the consequences. When children cannot enhance their own well-being and opportunities, adults may have to override their decisions and not grant self-determination. The obligation to honor their wishes is not as binding as it would be for an adult.

“In many parts of the world, adults who face serious illness or death are not privy to conversations about their care, because family and clinicians believe that it is kinder to exclude them.”40 Such cultural conflicts about how to apply the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence have the potential to cause serious problems when people travel from one country to another seeking medical care, or when patients or families from other countries receive healthcare in the United States. For example, older adolescents with serious illness may indicate a desire to discuss their prognosis and options with the medical team, while family members strongly object to telling the adolescent. Clinicians can help family members understand the importance of including the child, explaining to the family members that children understand a good deal about their diseases and even imminent death and that excluding them increases their suffering.40 Of course, some guardians remain adamant, and clinicians may have to choose between doing what they believe is best for the patients (by informing them) and honoring parental wishes. Other clinicians find that consultations with an ethics committee can help to resolve such conflicts.

The recognition that older children can understand a great deal and be competent to participate in many decisions has been recognized recently in the literature and in social policy.17,40 As children grow older, they are increasingly able to discuss and participate in health decisions relating to them. Some adolescents have gained authority to make healthcare decisions independently of their parents. Depending on state law, adolescents can get medical care such as contraceptives, contraceptive information and devices, abortions, and treatment for substance abuse without parental permission (i.e., legal emancipation by condition).17

The ideal situation is to have shared decision making and agreement among clinicians, family, and the child about what course to take. In the ordinary situation, however, parents or guardians have the authority to make decisions for the child’s medical care, just as for religion and schooling, unless they endanger the child. The child’s assent has been found to be increasingly important based on evidence that children with serious, chronic, or life-threatening illnesses understand a great deal and benefit from participating.2 In addition, the importance of their assent stems from understanding that they have the competence to make important contributions to these discussions.

Age of Consent: The Mature Minor in Law

State legislation increasingly recognizes that a “light-switch” (“bright line,” or purely age-related) rule regarding who is an adult may not be appropriate (see Table 24-1).17,82 Greater flexibility is emerging in legal interpretations that allow adolescents, although they are not legal adults, to make certain healthcare decisions. One path leading to adolescent consent authority follows case (common) law, in which courts have given specific meaning and scope to adolescents being sufficiently mature (i.e., the mature minor) to provide consent to treatment.17 This determination is subjective and is based on a case-sensitive analysis, dependent not only on the adolescent involved but also on the adolescent’s condition and the risks of treatment versus no treatment.

Perhaps the clearest guideline for the mature minor doctrine came in a Tennessee Supreme Court case that established the “Rule of Sevens”: (1) a minor under the age of 7 years lacks capacity; (2) a minor between 7 and 14 years of age is presumed not to have capacity, but that assumption can be rebutted (the burden is on the minor to show capacity); and (3) a minor 14 years of age or older is presumed to have capacity (the burden is on the one arguing against capacity).18 This rule was acknowledged to be case-sensitive and not a strict standard. As reiterated by a prominent legal authority, a minor’s consent should be effective if he or she is “capable of appreciating the nature, extent and probable consequences of the conduct consented to (e.g., medical treatment),” even if parental consent is “not obtained or is expressly refused.”17

States have codified a range of situations in which sufficiently mature minors can make their own healthcare decisions, providing exceptions to the rule of parental permission for certain healthcare conditions or based on the status of the minor.17 These statutes respond to clinician and patient concerns that a desire to seek care of a more sensitive nature (e.g., mental health or family planning services) might be impeded by a requirement for parental permission.30

The distinction between a mature minor and an emancipated minor has become blurred over time. Generally, mature minor consent authority relates to context-sensitive and specific situations, or conditions in which an adolescent demonstrates capacity to make decisions related to healthcare (Box 24-4), whereas emancipation represents a progression into adulthood linked with certain events that are viewed as conferring adult status. However, clinicians with specific questions are urged to consult local legal authorities for guidance.

Box 24-4 Minors as Healthcare Decision Makers: Characteristics Of Mature Minor For Healthcare

• Has experienced the illness for some time

• Understands the illness and the benefits and the burdens of treatment

• Has the ability to reason and has previously been involved in decision making about the illness

• Has a comprehension of death recognizing its personal significance and finality

Adapted from Leikin S: A proposal concerning decisions to forgo life-sustaining treatments for young people. J Pediatr 115:17-22, 1989.

Advance Directives and Substituted Judgment

Advance directives are used in framing healthcare decisions when the person has become incapacitated. These directives are statements made by the person who has decision-making capacity, stating how decisions should be made when they are unable to make decisions. Adults and some older children may have such directives in order to extend their control over events. Competent adults can use living wills or powers of attorney for healthcare to make known their views about how decisions should be guided and who should make decisions for them. In rare cases, minors can decide that they wish to make their views known.40 Although such decisions are not as controlling as those of legally competent adults, they can be morally binding. “Sometimes parents and children disagree about the sort of treatment that is appropriate at the end of life, with each making what the other regards as an inappropriate request. Whenever possible, clinicians should give the requests of the older minor serious consideration and seek a consensus among the family.”40

Exceptions to parents as decision makers

Informed Refusal of Care

Families who decline medical care for a child present the pediatric critical care unit team with an ethical dilemma: respect for the autonomy and privacy rights of the family and the importance of familial support for any therapeutic endeavor are in conflict with the duty to provide the best available care for the pediatric patient.69 The validity of parental consent for children has been taken for granted, although the presumption that parents invariably choose in their child’s best interests may at times be inaccurate. Rights are virtually never absolute and parents are not at liberty to destroy, maim, or neglect their children. The parents’ authority can be contested if the parents place their children at serious risk, such as by refusing to permit the critical care team to provide life-saving interventions to a child. The pediatric critical care unit team’s response to the parents’ refusal of treatment will depend on the clinical circumstances, the benefits and the burdens of treatment, and the child’s wishes in some cases.24

Parents may refuse interventions that have limited effectiveness, impose significant side effects, require chronic treatment, or are controversial. In such situations the parents’ informed refusals should be decisive.51 Refusal of such interventions might be ethically permissible even if the patient’s life expectancy might be shortened.

Parents sometimes refuse treatments for life-threatening conditions, although these treatments are highly effective in restoring the child to previous health, are short term, and have few side effects.7 It has been suggested that parents might refuse a medical recommendation for at least three categories of reasons: neglect, disagreement based on religions or other values, or inability to comply.46 Jehovah’s Witnesses commonly refuse blood transfusions for their children even when the child has suffered life-threatening hemorrhage or anemia. Similarly, Christian Scientist parents often refuse antibiotics for bacterial meningitis. Physicians who are unable to persuade parents to accept such interventions should seek a court order to administer the treatment.52,70 A court order is important because it signifies that society believes that the parent’s refusal is unacceptable.51 As one court declared, although “parents may be free to become martyrs themselves,” they are not free to “make martyrs of their children.”67

The American Academy of Pediatrics recognizes the “important role of religion in the personal, spiritual, and social lives of many individuals and cautions physicians and other healthcare professionals to avoid unnecessary polarization when conflict over religious practices arise. Nevertheless, professionals who believe that the parental religious convictions interfere with appropriate medical care that is likely to prevent substantial harm, suffering or death should request court authorization to override parental authority or, under circumstances involving imminent threat to a child’s life, intervene over parental objections.”3

Child’s Refusal of Care

In some cases children might refuse effective treatments. The physician’s response should be determined by the seriousness of the clinical situation, the effectiveness and side effects of treatment, the reasons for the child’s refusal, the parents’ preferences regarding treatment, and the burdens of insisting on treatment. It is difficult to force adolescents to take ongoing therapies, such as insulin shots for diabetes or inhalers for asthma. The most constructive approach is to try to understand the patient’s reasons for refusal, address them, and provide psychosocial support. In several cases adolescents have run away from home rather than accept cancer chemotherapy, which has significant side effects.82 Because it is physically difficult and morally troubling to force such treatment on adolescents, these refusals have been accepted, particularly when the parents have supported the child’s refusal. Sound ethical practice requires pediatric critical care unit professionals to respect the dignity of each adolescent patient by hearing and understanding the patient’s discussion of values and expressed concerns about medical treatment.82

Baby Doe Rules

The Federal Child Abuse Amendments of 1984 and subsequent regulations, commonly called Baby Doe Regulations, apply to decisions to withhold medical treatment from disabled infants younger than 1 year60; they limit the circumstances in which interventions may be withheld.

Under these regulations, treatment other than “appropriate nutrition, hydration, or medication”60 need not be provided if (1) the infant is chronically and irreversibly comatose; (2) the provision of such treatment would merely prolong dying, not be effective in ameliorating or correcting all of the infant’s life-threatening conditions, or otherwise be futile in terms of the survival of the infant; or (3) the provision of such treatment would be virtually futile in terms of the survival of the infant, and the treatment itself under such circumstances would be inhumane. The regulations note that decisions to withhold medically indicated treatment might not be based on subjective opinions about the child’s future quality of life. In addition, hospitals are encouraged to establish ethics committees, specifically infant care review committees, to advise physicians in difficult cases.

The Baby Doe Regulations have been sharply criticized.42,43 Many terms, such as appropriate and futile, are subject to conflicting interpretations. Most importantly, parents are not included in decision making despite their customary role as surrogates. The pediatric critical care unit team should appreciate that these regulations do not require them to provide treatment that, in their judgment, is inappropriate or futile.42

Inappropriate Care Requests

Parents may request inappropriate treatment for a number of reasons (Box 24-5). Many requests for inappropriate interventions are the result of miscommunications.40 Some of these miscommunications are embedded in social, ethnic, or religious differences. In some cases, families have unrealistic expectations, believe “everything must be done,” or are “waiting for a miracle.” Guilt and denial also may play a role in these irrational and unreasonable requests.40 Clinicians should show great sensitivity and patience in helping families come to terms with a diagnosis or prognosis.

Box 24-5 Potential Reasons That Parents Request Inappropriate Care

In some cases, families have a general mistrust of the healthcare system; this mistrust may appear to be vindicated by an unexpected and bleak prognosis.40 The family’s request for inappropriate treatment may be an expression of this mistrust. It is sometimes helpful to include someone whom the family can trust, such as a minister or family member with a healthcare background, who can help the family understand. In rare cases, the disagreement is truly a value disagreement in which family members may, for example, see maintaining someone in a persistent vegetative state as a positive value, whereas the clinicians do not. In these and other cases, healthcare professionals should maintain professional integrity and personal morality, but may find other clinicians willing to accept the families’ decisions. Substantial literature15,29,69,40 exists on how to respond to such situations, when to override parental requests, and the dangers of using decisions about what treatments are futile as mechanisms for rationing healthcare.

In general, it is important for the pediatric critical care unit professional to remember that most demands for inappropriate interventions are likely to be the result of poor communication and inadequate understanding. The pediatric critical care unit team must spend the time necessary to approach the specific ethical dilemma (see Box 24-1). Discussion with an ethics committee or an ethics consultant may help clarify the facts and points at issue and return the child to the central role, a role sometimes lost during heated disagreements.

Ethics of communication

The ethical dimensions of communication are expressed in the relationships that healthcare providers develop with their patients, society, and ultimately themselves.31 Society expects that patients will be treated with honesty and with respect for their autonomy. For pediatric patients who cannot speak for themselves, parents will be sought to address the best interests of the child. Depending on the relevant cognitive development of the child, however, his or her understanding and voice will be sought, whether it is to allow for information and education, to acquire individual assent, or to obtain real informed consent. All of these measures reflect the principle of respect, generally characterized in the adult setting as respect for autonomy.

The satisfaction of the patient, family, and provider may all be endangered when information is delivered poorly. The ethical dimensions of patient-provider communication represent the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, justice, and utility. Their practical application is represented in the four domains of veracity (truth-telling), privacy, confidentiality, and fidelity.31

Truth-Telling

Codes of medical ethics have traditionally ignored the obligations and virtues of veracity. The Hippocratic oath does not address veracity, nor does the Declaration of Geneva of the World Medical Association. As recently as 1980, the Code of Medical Ethics of the American Medical Association made no mention of veracity or truth-telling as either an obligation or a virtue, giving physicians unrestricted discretion about what to disclose to their patients; this changed in the 1997 edition of the code.6

In medicine, there is a long and distinguished tradition of providing less than the whole (unvarnished) truth.36,47,48 In The Silent World of Doctor and Patient, Katz shows that, from the time of Hippocrates until the late twentieth century, doctors routinely withheld the truth from patients and vigorously defended the morality of their decisions to do so.36 The arguments for withholding the truth varied. Some of the arguments were centered on the patient, arguing that the truth might be too difficult to bear. “Reassure the patient and declare his safety, even though you may not be certain of it,” wrote Isaac Israeli, a ninth-century physician, “for by this you will strengthen his Nature.”36 Other arguments focused on the physician and his moral obligation to foster hope. Thomas Percival, writing in the late eighteenth century, counseled doctors, “The physician should be the minister of hope and comfort to the sick.”36 Some of the arguments were economic, contending that doctors who admitted uncertainty would frighten and discourage patients and would soon go out of business. None of the arguments were apologetic.47

In light of this history, recent moral sentiment that the physician should tell the patient the truth—the whole truth, no matter how horrible it might be or how ill-prepared the patient might be—represents one of those mysterious changes in morality that occur from time to time, whereby something that was once thought morally intolerable is suddenly thought of as morally obligatory.47 When noting such a moral watershed, it is important to ask why the change occurred. Generally, it is not that morality itself changes. Instead, historical circumstances change so that people must react differently to new situations and reevaluate conventional moral wisdom.47

There are many reasons for the changes in attitude toward truth telling among physicians.31 Such reasons may include the availability of more treatment options, improved rates of survival, fear of malpractice suits, involvement of multiple team members in hospitals, altered societal attitudes about medicine in general, greater attention to patients’ rights, and increased recognition by physicians that communication is an effective means of enhancing patient understanding and compliance with healthcare.31

The obligation of veracity is based on the respect owed to others and is therefore rooted deeply in the principle of respect for patient autonomy.2,31,48 This obligation is the primary justification and basis for rules of disclosure in informed consent. The obligation of veracity exists even when consent is not an issue, and it is the guiding precept of the duty of respect toward others. Veracity is closely related to the obligations of fidelity and promise keeping.

When any two parties communicate, there is an implicit promise that both will speak truthfully and that they will not deceive each other.31 A patient becomes part of a contract, or a covenant, by entering into the therapeutic relationship. Although children may not legally be allowed to enter into formal contracts independent from their parents or guardians, the implied promise remains important. Such a contract includes the patient’s right to have his or her wishes respected regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment procedures. Cultural beliefs may affect the patient’s wishes, as might limitations on a family’s desire for full disclosure and informed consent.

Discerning the patient’s and family’s wishes can require experience, skill, listening, and time. In this truth-telling process, the health professional also expects to gain the right to truthful disclosures from the patient. Relationships between healthcare professionals and the patients and their parents ultimately depend on communication and trust. With respect to children, such dependence can be frustrating; although children are generally more honest and forthright than adults, they may act to protect their parents.31

There are certain culture-specific situations in which adult patients prefer not to receive complete information about their diagnosis and prognosis. Whether these feelings hold true for the children from these cultures has not been formally studied. Respect for autonomy suggests that cultural factors must be represented when considering disclosure to patients. Pellegrino warns against the use of assaultive truthfulness, suggesting that to “thrust the truth on a patient who expects to be buffered against news of impending death is a gratuitous and harmful misinterpretation of the moral foundations for respect for autonomy.”62

Parents of children and adolescents occasionally request that the physician not disclose a diagnosis or prognosis to the young patient. Such a request creates an ethical dilemma for the practitioner; the conflict between a duty to respect the parents’ wishes and a duty to tell the truth to the child.78

The authority of parents to direct the flow of information to the child and to organize and provide appropriate systems of emotional support is well recognized in pediatric care. Parents are regarded as moral agents for their children; pediatricians perceive that the integrity of the patient’s family is necessary to sustain and nurture the child. Still, parental authority cannot be absolute. A “best interest” standard that extends beyond parents’ wishes is recognized in nontreatment decisions for severely ill neonates and children, in the treatment of children whose parents have religious objection to usual care, and in the confidential care of adolescents.78

If there is a moral justification for lying to the patient or willfully hiding the truth, it must have a strength that overrides the principle of veracity derived from basic human respect. People deserve to be told the truth, and circumstances must be morally persuasive when considering deviating from this basic moral duty.31 One must ask whether concealing the diagnosis, not using the name of the disease, and not speaking to the child about prognosis will do more harm than good.

Confidentiality

The importance of confidentiality in medical practice has been acknowledged since ancient times.41 Respecting patients’ confidentiality usually promotes the moral principle of beneficence or the patients’ best interest. If patients are assured of confidentiality, they are more likely to be candid. Moreover, because privacy is what each of us wants for ourselves, it is only just to extend it to others. In addition, it is fair to adopt this policy of respecting confidentiality because, in a sense, patients own the information about themselves, and confidentiality honors their privacy and rights to control this information. If some information about the patient is released, such as a genotype for a late-onset genetic disease, it has the potential to cause harm through discrimination, labeling, or loss of self-esteem.

Concerns about confidentiality create a major barrier to effective healthcare for many adolescents.13 Adolescents are more likely to seek healthcare and to disclose personal information when they believe that the information will be kept confidential.

The clinician’s duty to maintain confidentiality, however, is not absolute. The presumption in favor of confidentiality can be overruled if there is a greater duty at stake or if there is a recognized exception.41 For example, an exception to the duty to maintain confidentiality is to protect a third party, as in intentional injury to children. If clinicians suspect that someone is abusing a child, they have a legal and moral duty to override confidentiality because a greater duty—the duty to protect the child—is present. In addition, there may be a duty to override confidentiality if there is a need to protect a patient from himself or herself; there may be such a duty if the minor is suicidal. There also may be a duty to protect the community that is greater than the duty to maintain someone’s confidentiality, such as a duty to report communicable diseases or gunshot wounds, regardless of the patient’s wishes.41

Breaking Bad News

Although breaking bad news is difficult and stressful for everyone, being uninformed is even more stressful for patients and families.14,31 One of the most common complaints of patients and families is the lack of accuracy, clarity, and consistency in the information provided.31 Family members indicate a willingness and desire to receive bad news as long as it is empathetically communicated.31

Sometimes, in response to their own pain, medical caregivers communicate the news of a bad prognosis in a brief encounter and may use technical terms to soften the blow, avoid the conversation altogether, or wait until the child is unconscious. Research on breaking bad news does not support the use of these techniques. Further discussion of this important topic is covered in Chapter 3.

Withholding and withdrawing therapy

Advances in pediatric critical care medicine have led to ethical issues of profound concern to all pediatric intensivists and nurses. One of the most striking developments in the past several years is that most children admitted to a pediatric critical care unit die after a decision is made to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatments.21,26,81,83 It is important that all healthcare professionals in the pediatric critical care unit be competent in end-of-life decision making and palliative care.

The decision to forgo life-sustaining treatment is made for up to 60% of terminally ill children83; 80% of the deaths that occur in the neonatal critical care unit are preceded by decisions to limit, withhold, or withdraw life support.39 Faced with decisions that challenge the very essence of the parenting role, parents of children in the pediatric critical care unit for whom withdrawal of life support has been recommended need to hear assurances that the healthcare team has not made the recommendation lightly.

The decision making at the end-of-life in the pediatric critical care unit is a dynamic process.26 Certainly, there must be acknowledgment of the value of the child and the child’s life, and acknowledgement of the sorrow of lifelong pain that such decisions evoke for parents.28 Parents also need to be assured that their child will not suffer and that all efforts will be made to control symptoms and allow the family to be with the child as much as desired and feasible. Pediatric critical care unit professionals must refrain from speaking about “withdrawal of care.” Although treatments may be withdrawn, care is never withdrawn. Care may be redirected from a focus on cure to a focus on comfort.

Despite extensive literature covering the ethical and legal aspects of withdrawal of therapy, little attention has been given to determining the optimal methods to withdraw it.72 Despite the lack of data on optimal management of some aspects of withdrawing life-sustaining treatments, a consensus exists regarding the ethical and clinical principles that should guide this care (Box 24-6).

Box 24-6 Principles of Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Treatments

• The goal of withdrawing life-sustaining treatments is to remove treatments that are no longer desired, no longer beneficial, or do not provide comfort to the patient.

• Withholding life-sustaining treatments is morally and legally equivalent to withdrawing them.

• Actions whose sole goal are to hasten death are morally and legally problematic.

• Any treatment can be withheld or withdrawn.

• Withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment is a medical procedure.

Modified from Rubenfield GD: Withdrawing life-sustaining treatment in the intensive care unit. Respir Care 45:1399-1407, 2000.

The Do-Not-Attempt-Resuscitation (DNAR) Order

The concept of doing less than everything possible to preserve the life of the patient is not new. The Hippocratic corpus advises physicians “to refuse to treat those who are overmastered by their diseases, realizing that in such cases medicine is powerless.”15 Even the earliest researchers in the field of resuscitation recognized that CPR should be used only in circumstances of reversible cardiac arrest. Unfortunately, no clear criteria exist for determining when cardiac arrest is irreversible.

In response to these concerns, many institutions have adopted procedure-specific DNAR orders. This approach is intended to reduce much of the ambiguity surrounding DNAR orders. The greatest advantage of the procedure-directed DNAR order is its clarity. This type of order must be supplemented with a detailed note in the chart explaining the justifications for the order and documenting the discussions between the clinicians and the patient or surrogate. By focusing on procedures, the form addresses in concrete terms exactly what will or will not be done in the event of a cardiorespiratory arrest. For example, Mittelberger and others56 found that the number of ambiguous DNAR orders was decreased from 88% to 7% after implementation of a procedure-specific DNAR order form. Two other studies have also documented improved communication among physicians and nurses after adopting procedure-specific DNAR order forms.32,61

DNAR replaced the older term do not resuscitate (DNR).57 DNAR presupposes that there is no guarantee that resuscitation attempts are going to be successful. This shift in terminology arose partly in response to the realization that the general public had a falsely optimistic perception of the success of resuscitation. The term DNAR is not, however, specific enough to stand alone; it also requires specific orders.57

Another controversy concerns whether it is necessary for physicians to obtain the consent for DNAR orders from the patient or the patient’s family.11,79 Many hospitals address this issue in internal hospital policies.54 Some hospitals, however, have adopted policies that permit physicians to write DNAR orders without the permission, or sometimes without the knowledge, of the patient or family. The presumption behind this approach is the view that CPR is a medical therapy and that physicians are uniquely qualified to determine whether and when a medical therapy is indicated. These policies are often referred to as CPR-not-indicated policies.84

There has been a recent call to modify the standard terminology further and replace the term DNAR with the term allow natural death (AND).38,57 Rather than emphasizing that something is being withheld, AND focuses on the benefits of allowing a natural process to take place. Although it initially seems to be a mere semantic issue, medial centers that have changed the terminology report easier conversations with patients and families about response to the end of life.57 It must be acknowledged that in the highly technologic environment, such as the pediatric critical care unit, the concept of “natural” death is rendered virtually meaningless.20

Not surprisingly, patients with DNAR orders often believe they have been abandoned by their caregivers. Indeed, it is often the case that physicians do in fact spend less time caring for patients who have DNAR orders. This is not appropriate, as patients with DNAR orders often need more attention in terms of aggressive palliative care than patients who are not imminently dying (see Chapter 3).

Withdrawal of Medically Provided Nutrition and Hydration

During the last two decades there has been a gradual consensus emerging in both law and ethics that medical nutrition and hydration can be withheld or withdrawn by the same standards that apply to other life-sustaining treatments. Specifically, it can be withheld or withdrawn after an analysis of the balance between the benefits and burdens of providing the therapy.22,34,49,53,58,66,77

Whereas this consensus has achieved wide acceptance among healthcare professionals caring for adult patients, professionals who care for children have been more reluctant to accept this approach.34,44,49 Decisions about the technologic administration or withdrawal of nutrition and hydration from a terminally ill child are among the most ethically troublesome that pediatric healthcare professionals face. Part of the reason for this difficulty may be the view that nutrition and feeding is such a basic and fundamental aspect of the care provided to children.

Providing food is deeply symbolic of nurturing, caring, and commitment in the human experience.44 The dilemma centers on whether food and fluids, provided by gastric and enteral tubes or parenteral administration, preserves life or prolongs death. Expert opinions range across the spectrum: from the belief that withholding or withdrawing food and fluids is active euthanasia to a perspective that administered nutrition and hydration will increase the dying persons’ discomfort and only delay the inevitable. Despite the fact that artificial nutrition and hydration is viewed by a majority of the U.S. Supreme Court44 as medical therapy that may be withheld, it is administered to a significant number of terminally ill patients.

Clinical experience, validated by research, has demonstrated that imminently dying persons experience loss of appetite and a natural process of dehydration. Organ systems function less efficiently until they fail, and the desire to eat and drink is lost.44 Clinical observations of hospice patients’ final stages indicate that most terminally ill patients do not experience hunger and often exhibit isotonic dehydration. Benefits from end-stage dehydration include the release of endogenous opioids and the analgesic affect of ketosis.44 There is decreased urine output, diminishing incontinence; lessened edema, decreasing the risk of pressure ulcers; and reduced pulmonary and gastric secretions, relieving congestion, coughing, and vomiting.44 With total parenteral nutrition, the adverse effects of fluid overload, local bleeding and infection, and sepsis may be significant and shorten life while diminishing its quality.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has recently concluded that the withdrawal of medically administered fluids and nutrition for pediatric patients is ethically acceptable in limited circumstances.22 As always, when particularly difficult or controversial decisions are being considered, consultation with experts in ethics is strongly recommended.

There is a cost of caring

The pediatric critical care unit is a stressful environment because of high patient acuity, morbidity and mortality, daily confrontations with ethical dilemmas, and a tension-charged atmosphere.1 The cumulative effect on the pediatric critical care unit professional can include significant caregiver suffering.55,65,71,73 Several concepts—burnout, compassion fatigue, moral distress and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—are related to the concept of caregiver suffering.

Burnout is “a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion caused by long-term involvement in emotionally demanding situations.”64 Burnout syndrome has been identified in a high percentage of pediatric critical care unit nurses and nursing assistants.65 Burnout syndrome emerges gradually and is the result of emotional exhaustion and job stress. In contrast, compassion fatigue is characterized by a sense of helplessness, confusion, and isolation from supporters, which can have a more rapid onset and resolution than burnout.73

After exposure to a traumatic event, individuals with PTSD experience symptoms of persistent recollections, avid reminders of the events, and have symptoms of increased arousal.86 Critically ill patients, adult and pediatric, who survive their hospitalization can have symptoms of PTSD.19,33,37,75 In addition, a high percentage of family members of pediatric critical care unit patients report PTSD symptoms.8,45,55 Critical care nurses have also been reported to have PTSD symptoms.55

Moral distress occurs when an individual is unable to translate his or her moral choice into action.73 As previously mentioned, acting in a manner contrary to personal or professional values undermines the individual’s sense of integrity. When healthcare professionals cannot live up to their personal values by acting in an ethical manner, their suffering is compounded by moral distress.73 Caregiver suffering takes a toll on the individual healthcare professional and on the workplace, causing decreased productivity, more sick days, and higher nursing turnover.55

Recommendations for protecting pediatric critical care unit professionals from the cumulative and complicated effects of caregiver suffering include three tiers of strategies: personal, professional, and organizational.71 In caring for the caregivers, the challenge for healthcare organizations lies in developing respect and care for their employees in the same way that they require their employees to care for patients. Further information regarding signs, symptoms, and treatment of caregiver suffering can be found in the Chapter 24 Supplement on the Evolve Website.

1 Acker K.H. Do critical care nurses face burnout, PTSD, or is it something else? Getting help for the helpers. AACN Clin Issues Crit Care Nurs. 1993;4:558-565.

2 American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Bioethics. Informed consent, parental permission, and assent in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 1995;95:314-317.

3 American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Bioethics. Religious objections to medical care. Pediatrics. 1997;99:279-281.

4 American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Hospital Care. Family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3):691-696.

5 American Association of Critical Care Nurses. AACN standards for establishing and sustaining healthy work environments: a journey to excellence. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14(3):187-197.

6 American Medical Association, Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. Code of Medical Ethics: current opinions with annotations. Chicago: American Medical Association; 1997.

7 Asser S.M., Swan R. Child fatalities from religion motivated medical treatment. Pediatrics. 1998;101:625-629.

8 Azoulay E., et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:987-994.

9 Beauchamp T.L., Childress J.F. Principles of biomedical ethics, ed 4. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994.

10 Belitz J., Baley R.A. Clinical ethics for the treatment of children and adolescents: a guide for general psychiatrists. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;32:243-257.

11 Blackhall L.J. Must we always use CPR? N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1281-1285.

12 Bluebond-Langer M. The private world of dying children. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1978.

13 Brindis C., et al. Adolescents’ access to health services and clinical preventive health care: crossing the great divide. Pediatric Annals. 2002;31:575-581.

14 Buckman R. How to break bad news: a guide for health care professionals. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1992.

15 Burns J.P., Truog R.D. Ethical controversies in pediatric critical care. New Horizons. 1997;5:72-84.

16 Cameron M.A., Schleien C.L., Morris M.L. Parental presence on pediatric intensive care rounds. J Pediatr. 2009;155:522-528.

17 Campbell A.T. Consent, competence and confidentiality related to psychiatric conditions in adolescent medicine practice. Adolesc Med. 2006;17:25-47.

18 Cardwell v. Bechtol, 724 S.W.2d 739 (Tenn. 1987)

19 Colville G. The psychological impact on children of admission to intensive care. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2008;55:605-616.

20 Copnell B. Death in the pediatric ICU: caring for children and families at the end of life. Crit Care Nurs Clin N Am. 2005;17:349-360.

21 Deviator D., Latour J.M., Tissieres P. Forgoing life-sustaining or death-prolonging therapy in the pediatric ICU. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2008;55:791-804.

22 Dickema D.S., Botken J.R. Clinical report: forgoing medically provided nutrition and hydration in children. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):813-822.

23 Dingeman R.S., et al. Parent presence during complex invasive procedures and cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2007;120:842-854.

24 Fleishman A.R., et al. Caring for gravely children. Pediatrics. 1998;101:625-629.

25 Freyer D.R. Care of the dying adolescent: special considerations. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):381-388.

26 Garros D., Rosychuk R.J., Cox P.N. Circumstances surrounding end-of-life in a pediatric intensive care unity. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e371-e379.

27 Granulspacher G.P., Howell J.D., Young M.J. Perception of ethical problems by nurses and doctors. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:577-578.

28 Greig-Midlane H. The parents’ perspective on withdrawing treatment. BMJ. 2001;323:390-395.

29 Hardart G.E., DeVictor D.J., Traog R.D. Ethics. In: Nichols D.G., editor. Rogers textbook of pediatric intensive care. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:180-194.

30 Hartman R.G. Coming of age: devising legislation for adolescent medical decision-making. Am J Law Med. 2002;28:409-453.

31 Hays R.M., et al. Communication at the end of life. In: Carter B.S., Levetown M., editors. Palliative care for infants, children, and adolescents. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2004:112-140.

32 Heffner J.E., Barbieri C., Casey K. Procedure-specific do-not-resuscitate orders—effect on communication of treatment limitations. Arch Intern Med. 1994;156:793-797.

33 Hobbie W.L., et al. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:4060-4066.

34 Johnson J., Mitchell C. Responding to parental requests to forego pediatric nutrition and hydration. J Clin Ethics. 2000;11:128-135.

35 Jonsen A.R., Siegler M., Winslade W.J. Clinical ethics: a practical approach to ethical decisions in clinical medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 1992.

36 Katz J. The silent world of doctor and patient. New York: Free Press; 1984.

37 Kenardy J.A., Spence S.H., McLeod A.C. Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder in children after accidental injury. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):1002-1009.

38 Knox C., Vereb J.A. Allow natural death: a more humane approach to discussing end-of-life directives. J Emerg Nurs. 2005;31(6):560-561.

39 Kopelman A.E. Understanding, avoiding and resolving end-of-life conflicts in the NICU. Mount Sinai J Med. 2006;73(3):580-586.

40 Kopelman L.M. Ethical and legal issues. In: Perkin R.M., Newton D.A., Swift J., Anas N., editors. Pediatric hospital medicine: textbook of inpatient management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:39-47.

41 Kopelman L. Confidentiality. In: Perkin R.M., Newton D., Swift J., Anas N., editors. Pediatric hospital medicine: textbook of inpatient management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:43-44.39.

42 Kopelman L.M. Are the 21 year old Baby Doe Rules misunderstood or mistaken? Pediatrics. 2005;115:797-802.

43 Kopelman L.M., Irons T.G., Kopelman A.E. Neonatologists judge the “Baby Doe” regulations. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:677-683.

44 Kyba F.C. Legal and ethical issues in end-of-life care. Crit Care Nurs Clin N Am. 2002;14:141-155.

45 Landolt M.A., et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in paediatric patients and their patients: an exploratory study. J Paediatr Child Health. 1998;34:539-543.

46 Lantos J.D. Treatment refusal, noncompliance, and the pediatrician’s responsibilities. Ped Ann. 1989;18:255-260.

47 Lantos J.D. Should we always tell children the truth? Perspect Biol Med. 1996;40(1):78-92.

48 Leiken S. An ethical issue in pediatric cancer care: nondisclosure of a fatal prognosis. Pediatr Ann. 1981;10(10):401-407.

49 Levi B.H. Withdrawing nutrition and hydration from children: legal, ethical, and professional issues. Clin Pediatr. 2003;42:139-145.

50 Lo B.: Resolving ethical dilemmas: a guide for clinicians. . Philadelphia; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins:2005:4-9

51 Lo B.: Resolving ethical dilemmas: a guide for clinicians. . Philadelphia; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins:2005:235-242

52 Macklin R. Consent, coercion and conflict of rights. Perspect Biol Med. 1977;20:365-366.

53 McCann R.M., Hall W.J., Groth-Juncker A. Comfort care for terminally ill patients: the appropriate use of nutrition and hydration. JAMA. 1994;272:1263-1266.

54 McClung J.A., Kamer R.S. Legislating ethics: implications of New York’s do-not-resuscitate law. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:270-272.

55 Meader M.L., et al. Increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in critical care nurses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:693-697.

56 Mittelberger J.A., et al. Impact of procedure-specific do-not-resuscitate order form on documentation of do not resuscitate orders. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:228-232.

57 Morrison W., Berkowitz I. Do not attempt resuscitation orders in pediatrics. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2007;54:757-771.

58 Nelson R.M. Ethics in the intensive care unit: creating an ethical environment. Crit Care Clin. 1997;13(3):691-701.

59 Nelson L.J., et al. Forgoing medically provided nutrition and hydration in pediatric patients. J Law Med Ethics. 1994;23:33-46.

60 Nondiscrimination on the basis of handicap; procedures and guidelines relating to healthcare for handicapped infants—HHS. Final rules. Fed Regist. 1985;50:14879-14892.

61 O’Toole E.E., et al. Evaluation of a treatment limitation policy with a specific treatment-limiting order page. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:425-432.

62 Pelligrino E. Is truth telling to the patient a cultural artifact? JAMA. 1992;268:1734-1735.

63 Phipps L.M., et al. Assessment of parental presence during bedside pediatric intensive care unit rounds: effect on duration, teaching and privacy. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8:220-224.

64 Pines A.M., Aronson E. Career burnout: causes and cures. New York: Free Press; 1988.

65 Poncet M.C., et al. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:698-704.

66 Porta N., Frader J. Withholding hydration and nutrition in newborns. Theor Med Bioeth. 2007;28:443-451.

67 Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S.; 158 (1944)

68 Pruitt L.M., et al. Parental presence during pediatric invasive procedures. J. Pediatr Health Care. 2008;22:120-127.

69 Ridgway D. Court-mediated disputes between physicians and families over the medical care of children. Arch Pediatr Adoles Med. 2004;158(9):891-896.

70 Rosen P. Religious freedom and forced transfusion of Jehovah’s Witness children. J Emerg Med. 1996;14:241-243.

71 Rourke M.T. Compassion fatigue in pediatric palliative care providers. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2007;54:631-644.

72 Rubenfield G.D. Withdrawing life-sustaining treatment in the intensive care unit. Respir Care. 2000;45(11):1399-1407.

73 Rushton C.H. The other side of caring: caregiver suffering. In: Carter B.S., Levetown M., editors. Palliative care for infants, children and adolescents. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2004:220-243.

74 Rushton C.H., Brooks-Brunn J. Environments that support ethical practice. New Horiz. 1997;5(1):20-29.

75 Schelding G., et al. Health-related quality of life and post-traumatic stress disorder in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:651-659.

76 Schexnayder S.M., Bryant P.H.I., Fiser D.H. The family is the patient. In: Fuhrman B.P., Zimmerman J.S., editors. Pediatric critical care. St Louis: Mosby; 1998:38-42.

77 Schwarte A.M. Withdrawal of nutritional support on the terminally ill. Crit Care Nurs Clin N Am. 2002;14:193-196.

78 Sigman G.S., Kraut J., LaPluma J. Disclosure of a diagnosis to children and adolescents when parents object: a clinical ethics analysis. AJDC. 1993;147:764-768.

79 Snider G.L. The do-not-resuscitate order: ethical and legal imperative or medical decision. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:665-674.

80 Sulmasy D.P. What is conscience and why is respect for it important? Theor Med Bioeth. 2008;29:135-149.

81 Tan G.H., et al. End-of-life decisions and palliative care in a children’s hospital. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(2):332-342.

82 Traugott I., Alpers A. In their own hands: adolescents refusal of medical treatment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(9):922-927.

83 Vose L.A., Nelson R.M. Ethical issues surrounding limitation and withdrawal of support in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 1999;14:220-230.

84 Waisel D.B., Truog R.D. The cardiopulmonary resuscitation-not-indicated order: futility revisited. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:304-308.

85 Weir R.F., Peters C. Affirming the decisions adolescents make about life and death. Hasting Cent Rep. 1997;27(6):29-40.

86 Yehunda R. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:108-114.

87 Zawistowski C.A., Frader J.E. Ethical problems in pediatric critical care: consent. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(suppl 5):S407-S410.

Be sure to check out the supplementary content available at

Be sure to check out the supplementary content available at