Ethical Issues

Differences between Morals and Ethics

Morals are the “shoulds,” “should nots,” “oughts,” and “ought nots” of actions and behaviors, and they are related closely to cultural and religious values and beliefs that govern our social interactions. Morals form the basis for action and provide a framework for the evaluation of behavior.1

Ethics are concerned with the basis of the action rather than whether the action is right or wrong, good or bad. Imposition of ethics implies that an evaluation is being made that is based on or derived from a set of standards. It refers to what rules are required to prevent harm to persons and to the collective beliefs and values of a community or profession.1

Moral Distress

Recently, moral distress has been a topic widely discussed in the literature as a serious problem for nurses.2–5 Nurses face multiple challenges on a daily basis: emergency situations, tension from conflict with others, complex clinical cases, new technologies, increasing regulatory requirements, acquisition of new skills/knowledge, staffing issues, financial constraints, workplace violence, to name a few. This care environment has led to increasingly complex moral and ethical dilemmas.5 In addition, they frequently may experience emotional outbursts from patients, families, co-workers, and feel a lack of control and “burnt out.”2,5 Moral distress occurs when a person knows the ethically appropriate action to take but cannot act on it. It also manifests when a nurse acts in a manner contrary to personal and professional values. As a result, there can be significant emotional and physical stress that leads to feelings of loss of personal integrity and dissatisfaction with the work environment. Relationships with co-workers and patients are affected, and the quality of care can be negatively affected. There is also a great impact on personal relationships and family life; nurses experiencing moral distress may resign their position or leave the profession entirely.3

It is therefore important that nurses recognize moral distress and actively seek strategies to address the issue through institutional, personal, and professional organizational resources. Knowledge and application of ethical principles and guidelines can assist the nurse in daily practice when ethical dilemmas occur. Box 2-1 provides a position statement on moral distress, promulgated by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN).6 The document is evidence-based, providing additional references for the reader. There is also a reference to ensuring that support to alleviate moral distress is present in a healthy work environment (see Chapter 1). Actions are listed for direct care staff nurses as well as employers.

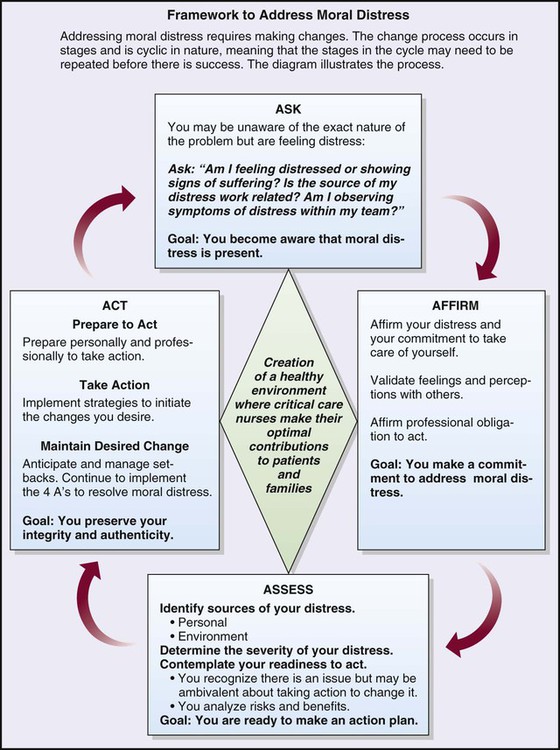

The AACN has created a framework—The 4A’s to Rise Above Moral Distress—to support nurses who are experiencing moral distress (Figure 2-1). ASK, the first stage, is a self-awareness and reflection period in which one becomes more aware of the distress and its effects on oneself. Specific areas to address are physical, spiritual, emotional, and behavioral responses. During stage two, AFFIRM, one affirms the distress and makes a commitment to take care of oneself. In stage three, ASSESS, one needs to identify the timing and context of when the stressors occur; determine the severity of the distress; and examine one’s readiness to act. The final stage, ACT, consists of preparation, the action itself, and maintaining the desired change. Although the model was created by AACN, it is a framework that can be used in diverse settings and by various health care professionals.7 McCue8 reported using this model as a resource for resolving an issue between a chief nurse executive and chief executive officer. In this case, the impact of the outcome was at the organizational level.

Moral Courage

In order to avoid moral distress, nurses must feel free to advocate for themselves, their patients, co-workers, and a safe and effective work environment. Lachman and colleagues describes moral courage as “the willingness to stand up for and act according to one’s ethical beliefs when moral principles are threatened, regardless of the perceived or actual risks (such as stress, anxiety, isolation from colleagues, or threats to employment)”.9,p24 They describe organizational cultures that support moral courage, the importance of peer support, education, and policies that can support moral courage of staff. Other authors have reported that moral courage is needed in everyday practice and that one must act ethically even in the presence of risk.4,10

Ethical Principles

Certain ethical principles were derived from classic ethical theories that are used in health care decision making. Principles are general guidelines that govern conduct, provide a basis for reasoning, and direct actions. The six ethical principles that are discussed in this chapter are autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, veracity, fidelity, and justice (Box 2-2).

Autonomy

The concept of autonomy appears in all ancient writings and early Greek philosophy. In health care, autonomy can be defined as an agreement to respect another’s right to self-determine a course of action and the support of independent decision making11 without coercion or interference from others. Autonomy is a freedom of choice or a self-determination that is a basic human right. It can be experienced in all human life events.

The critical care nurse is often “caught in the middle” in ethical situations, and promoting autonomous decision making is one of those situations. As the nurse works closely with patients and families to promote autonomous decision making, another crucial element becomes clear. Patients and families must have all of the information about a particular situation before they can make a decision that is best for them. They should be given all the pertinent information and facts, and they must have a clear understanding of what was presented. This is where the nurse is a most important member of the health care team—as patient advocate, the nurse provides more information as needed, clarifies points, reinforces information, and provides support during the decision-making process. Box 2-3 presents the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) feature on nursing intervention activities that facilitate decision making.

Beneficence

The concept of doing good and preventing harm to patients is the sine qua non for the nursing profession. However, the ethical principle of beneficence—which requires a nurse to promote the well-being of patients—points to the importance of this duty for the health care professional. The principle of beneficence presupposes compassion; taking positive action to help others; desire to do good. It is the core principle of patient advocacy.11 Harms and benefits are balanced, leading to positive or beneficial outcomes. In approaching issues related to beneficence, conflict with another principle, that of autonomy, is common. Paternalism exists when the nurse or physician makes a decision for the patient without consulting the patient.

Fidelity

Another ethical principle that is closely related to autonomy and veracity is fidelity. Fidelity, or faithfulness and promise-keeping to patients, is an essential aspect of nursing. The American Nurses Association (ANA) states that this principle requires loyalty, fairness, truthfulness, advocacy, and dedication to our patients. It involves an agreement to keep our promises. Fidelity refers to the concept of keeping a commitment and is based on the virtue of caring.11 It forms a bond between individuals and is the basis of all professional and personal relationships. Regardless of the amount of autonomy that patients have in critical care areas, they still depend on the nurse for many types of physical care and emotional support. A trusting relationship that establishes and maintains an open atmosphere is one that is positive for all involved.

Privacy also has been described as being inherent in the principle of fidelity. It may be closely aligned with confidentiality of patient information and a patient’s right to privacy of his or her person, as in maintaining privacy for the patient by pulling the curtains around the bed or making sure that he or she is adequately covered. The ANA summary and principle on privacy and confidentiality are found in Box 2-4.

Justice

The principle of justice is often used synonymously with the concept of allocation of scarce resources. According to the ANA, it is based on analysis of benefits and burdens of decisions. Justice implies that all have equal rights and that there be a fair and equal distribution of resources to all.11 Contrary to the belief of many people, health care is not a right guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States. Rather, it is the access to health care that should be provided to all people. With escalating health care costs, expanded technologies, an aging population with its own special health care needs, and in some instances a scarcity of health care personnel, the question of how to allocate health care becomes even more complex.

Withholding and Withdrawing Treatment

In order to accomplish a positive outcome for the patient, family, and health care providers, a plan for this complex and difficult process must be established. Stacy reported a case study that described nursing management of an adult patient undergoing withdrawal of mechanical ventilation as part of an end-of-life protocol. The clinical nurse specialist was instrumental in coordinating a patient care conference that included all involved members of the health care team along with family members. Key to the process that followed was symptom management, clear communication among health care team and family, determining the procedure for withdrawal of mechanical ventilation, and documentation of the care. Another key component is bereavement debriefing for the health care team, which ideally occurs several days after the event.12

Medical Futility

The concept of medical futility has resulted in various discussions and proposed criteria or formulas to predict outcomes of care.13–14 Medical futility has a qualitative and a quantitative basis and can be defined as “any effort to achieve a result that is possible but that reasoning or experience suggests is highly improbable and that cannot be systematically reproduced.”13 Quantitative futility was based on statistical calculations and assumed to be objective. However, there is no agreement regarding statistical thresholds for treatments to be considered futile.15 Qualitative futility is subjective and has no consistency in agreement.14 Hofmann and Schneiderman indicate that “Death is not necessarily a medical failure; a bad death is not only a medical failure, but also an ethical breakdown”.16

Ethics as a Foundation for Nursing Practice

A professional ethic forms the framework for any profession17 and is based on three elements: 1) the professional code of ethics; 2) the purpose of the profession; and 3) the standards of practice of the professional. The code of ethics developed by the profession is the delineation of its values and relationships with and among members of the profession and society. The need for the profession and its inherent promise to provide certain duties form a contract between nursing and society. The professional standards describe specifics of practice in a variety of settings and subspecialties. Nursing professionals must stay consistent with their values and ethics, and ensure that the ethical environment is maintained wherever nursing care and services are performed.18–19 Each element is dynamic, and ongoing evaluations are necessary as societal expectations change, technologies increase, and the profession evolves.

Nursing Code of Ethics

The ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses20 provides the major source of ethical guidance for the nursing profession. The nine statements of the code are found in Box 2-5. Further delineation of each of the provisions along with in-depth discussion and examples of application can be found on the ANA website, www.nursingworld.org.

Ethical Decision Making in Critical Care

The Nurse’s Role

Benner21 described the concept of the relational ethics of comfort, touch, and solace and questioned whether it is an endangered art lost to times past. However, she and her colleagues did find that there are still many examples of such comforting in daily practice, despite the overwhelming emphasis on using technologies in treating critically ill patients. Voice and touch are described as being central for the patient recovering from anesthesia. Critical decisions such as the conservative uses of restraints are another example related to comfort and ethical care of patients. Lachman described the ethics of caring to nursing practice. Through the very decision to become a nurse, one makes a moral commitment to provide care and services for patients, and that indicates a focus on meeting all the needs of patients.22 Acknowledging the importance of the nurse-patient relationship and establishing time to listen, explain, and comfort can assist the nurse in determining unmet needs of patients. Box 2-6 presents the NIC feature on values clarification.

As discussed earlier, the critical care nurse encounters ethical issues on a daily basis. Pavlish and colleagues studied nurses’ ethically difficult situations, their early indicators and risk factors, nurse actions, and outcomes. From this study, they derived risk factors for patients, families, health care providers, and health care organizations. Additionally, they delineated early indicators for ethical dilemmas in six areas (Box 2-7).23

Health care organizations and authors have emphasized that responding to individual ethical issues is not enough and that there must be a plan in place that asserts a systematic approach for proactively addressing ethical situations.24–25 This program should identify, prioritize, and address concerns about ethics at an organizational level. Thus, measurable improvements will be able to demonstrate reduced disparities between current practices and ideal practices.24 Epstein described an intervention in which the role of the critical care nurse is essential in early identification of potential ethical issues, i.e., preventative ethics.25 Sample questions to consider are listed in Box 2-8.

One common practice for nurses on a daily basis is their oncoming and “hand-off” patient report. Rushton reports that nurses may overlook common issues and potential ethical violations. She offers several strategies to ensure an ethically grounded nursing shift report26 (Box 2-9). Another patient care issue that arises is when the critically ill patient needs a surrogate decision maker. Especially difficult is when that patient has no family member or is otherwise from a vulnerable and/or marginalized population. There are major concerns when clinicians serve as both the clinical and the surrogate for the patient. The decision must be made by someone other than the treating clinician, considering procedural fairness for the situation.27

Ethical conflicts occur frequently in the health care setting. Negative outcomes of such conflicts are in the areas of staff morale, operational and legal costs, and public relations. It is essential that the health care organization has methods in place to address ethical issues. Because the nurse is on the front line with issues such as do not resuscitate (DNR) orders, response to treatments, and application of new technologies and protocols, he or she may be the one person who best knows the patient’s and family’s wishes about treatment prolongation or cessation. It is therefore important that the nurse be included as a member of the health care team that determines ethical dilemma resolution. Box 2-10 presents a sample of ethics-related resources.

What Is an Ethical Dilemma?

In general, ethical cases are not always clear-cut. An ethical dilemma exists if there are two (or more) morally correct actions that cannot be followed. The result is that both something right and something wrong occur. In these situations, there are both ethical conflict and ethical conduct issues.28 The most common ethical dilemmas encountered in critical care are forgoing treatment and allocating the scarce resource of critical care, but how does the health care worker know that a true ethical dilemma exists?

Before any decision model is applied, it must be determined whether a true ethical dilemma exists. Criteria for defining moral and ethical dilemmas in clinical practice are threefold: 1) an awareness of the various options; 2) an issue that has options; and 3) two or more options with true or “good” aspects, with the choice of one option compromising the option not chosen. One must pause, expand group consciousness about the issue, validate assumptions, look for patterns of thoughts or behaviors, and facilitate reflection and inquiry prior to making any decision.29

Steps in Ethical Decision Making

To facilitate the ethical decision-making process, a model or framework must be used so that all involved will consistently and clearly examine the multiple ethical issues that arise in critical care. There are various ethical decision-making models in the literature.30–31 Box 2-11 lists steps in an ethical decision-making model that will be briefly discussed in this chapter.

Step Five

Personal values, beliefs, and moral convictions of all involved in the decision process need to be known. Whether actually achieved through a group meeting or through personal introspection, values clarification facilitates the decision process. See the NIC feature on values clarification in Box 2-6.

Strategies for Promotion of Ethical Decision Making

Inservice and Education Programs

Basic education about ethical principles and decision making is an important first step in facilitating ethical decision making among nursing staff in the critical care area.32–33 It is important for nurses to examine their own values, beliefs, and moral convictions. Nurses need to know and use the ANA Code for Nurses in their daily clinical practice. Treatment choices for patients and ethical issues involving patients, nurses, and medical colleagues must be explored and discussed in the classroom setting, where no time constraints or extraneous distractions exist to interrupt the decision-making process. Use of the nursing process as a framework can be a teaching strategy for understanding ethical issues1 (Box 2-12).

Nursing Ethics Committees

Nursing ethics committees provide a forum in which nurses can discuss ethical issues that are pertinent to nurses at the individual, the unit, or the department level.32–33 Unlike the IEC, which involves treatment choices for patients, the nursing committee may or may not address a patient situation. Depending on the specific goals of the committee, it can also serve as a resource to nursing staff, make recommendations to a policy-making body about a variety of professional issues, or actually formulate policies. It also may serve to educate the department on ethical and professional issues. Membership usually comprises representatives from all major clinical areas or divisions, educators, clinical nurse specialists, administrators, and other specialty staff. Some departments, such as critical care, may have their own unit or division committee.

Ethics Rounds and Conferences

Ethics rounds at the unit level regarding patients in the unit can be done by nurses on a weekly or other established basis. Rounds educate the staff about problems and can have preventive effects when facilitated appropriately. During the discussion, potential problems may be identified early, and actions may be taken to decrease or prevent the incidence of a problem. An individual patient ethics conference may be scheduled to include only the nursing staff or to include a multidisciplinary group to discuss unit issues.32–33 A patient ethics conference may function as a liaison with the IEC or as an end in itself.

Summary

• Ethical dilemmas are encountered daily in the practice of critical care.

• The AACN statement on moral distress and framework to address moral distress provide insight and guidelines for critical care nurses who experience moral distress.

• The critical nature of the situation and the speed that is required to make decisions often prevent practitioners from gaining insight into the desires, values, and feelings of patients.

• By assuming a solely technologic approach, practitioners violate the rights of patients and their professional codes of ethics.

• By using an ethical decision-making process, practitioners protect the rights of the patient, and logical analysis of the case leads to a decision that is made in the best interests of the patient.

• It is through moral reasoning and examining, weighing, justifying, and choosing ethical principles that patient’s rights and individuality are upheld.

• The practice of nursing is built on a foundation of moral and ethical caring; the critical care nurse is pivotal in identifying patient situations with an ethical component and can participate in the decision-making process to address the issues.