Ethical Considerations in Managing Critically Ill Patients

THE DOCTOR-PATIENT RELATIONSHIP

Decision Making for Cognitively Impaired Patients

Avoiding Conflicts in the Intensive Care Unit

THE ETHICS OF END-OF-LIFE CARE

Withholding and Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Treatments

Advance Care Directives and Durable Powers of Attorney

Critical illnesses and the interventions necessary to address them pose many ethical dilemmas for clinicians. Therefore, it is not surprising that critical care physicians encounter ethical dilemmas more often than do general internists.1 The most frequent predicaments relate to end-of-life care, including decisions about termination of medical treatment, respect for patient autonomy, and conflicts among various parties involved in patient care. Less frequent quandaries stem from concerns about equitable use of resources, truth telling, religious and cultural differences, and professional conduct. On rare occasions, critical care providers must be prepared to address the extraordinary demands related to disasters because the skills and resources at their command offer key components of a well-organized disaster response.

The Doctor-Patient Relationship

As a rule, clinicians should follow the same ethical guidance in critical care situations as in less stressful contexts:2 They should treat patients with respect. They should deal honestly with patients and should not reveal confidences entrusted to them, unless the well-being of others is threatened. They should act in good faith, keep promises and commitments, and try faithfully to meet fiduciary responsibilities to patients.

At the same time, ICU staff must balance competing moral obligations that may limit or override obligations to fidelity to one particular patient, such as the needs of other patients who are currently under their care or may need their care in the future. Various models of decision making have been proposed—ranging from an informative model, in which patients make the decisions quite independently after the clinician has offered sufficient information, to a more paternalistic model, in which clinicians make decisions based on their judgment of what is in the best interest of the patient.3 A commonly accepted model today is a deliberative model, in which the clinician gives the patient information about his or her condition and the medical options, along with their advantages and disadvantages, and the patient explains his or her values and preferences, and together they reach a treatment decision. This model must be adapted to the extreme circumstance of critical illness.4,5 Leaders in the field of critical care medicine have endorsed a model of decision making, shared decision making, that recognizes that patients and their surrogates will vary in their desire to participate in decision making, but generally all will feel most comfortable with decisions if they have been given sufficient information to be able to understand and trust the decision process.6–9

Most physicians do not follow the same model with every patient or in every encounter. Regardless of the model adopted, clinicians should heed the elements of good ethical practice when making their decisions (Box 71.1). ICU clinicians also should be attentive to the many facets of patients’ lives that influence their views and preferences. For example, patients’ families play a large role in shaping their experiences and beliefs and in supporting them, particularly when they are sick. Ethicists in North America initially took an approach to patient autonomy that ignored the family, but more recent thought has recognized the importance of the family’s supportive role.10,11

Clinicians also should be sensitive to the needs of the family when a patient is sick.12 Among these, according to a survey of family members in ICU waiting rooms, are the need to talk about negative feelings such as guilt and anger; to talk about the possibility of the patient’s death; to be told what to expect before they go into the ICU for the first time; to visit at any time; to talk to the same nurse every day; to receive explanations that are understandable; to feel that there is hope; to have good food available in the hospital; to be assured that it is all right to leave the hospital for a while; and to feel accepted by the staff.13

Members of the ICU staff also should take note of the religious affiliation and cultural identity of their patients. However, they should not stereotype patients and presume to know what patients want based on their affiliation, but rather should be ready to inquire about each patient’s views and should be respectful of diverse beliefs14,15 (Box 71.2).

Communication with Patients

Often, the ICU clinician must convey bad news. Recommendations for breaking bad news include the following16:

• Use a location that is comfortable, quiet, and private.

• Set aside adequate time for discussion.

• Check what the patient or family already knows.

• Give some warning that there will be unfortunate news.

• Let the patient’s desire for information guide the discussion.

• Elicit and address the patient’s reactions and concerns.

Communication with ventilated patients is particularly difficult. Clinicians should make every effort to use techniques designed to overcome communication barriers with ventilated patients.17

Decision Making for Cognitively Impaired Patients

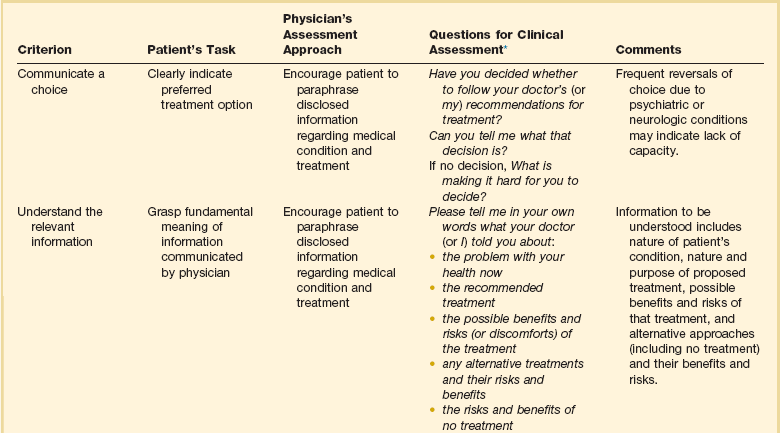

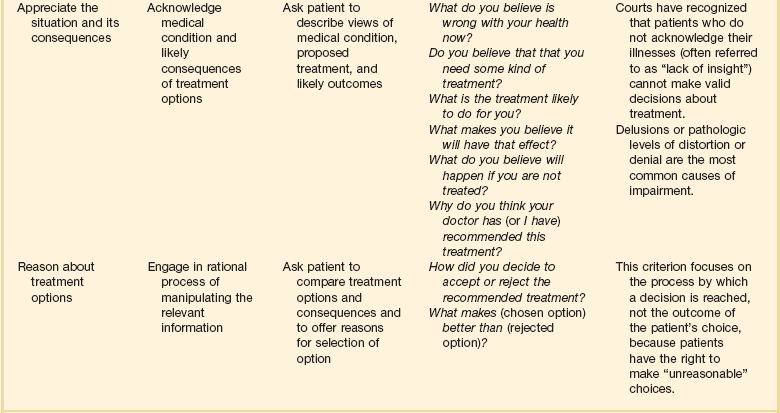

Because many patients are, or may become, cognitively impaired, clinicians should frequently and repeatedly assess patients’ capacity to understand their situation and make decisions. Judging the capacity of patients to make decisions can be difficult.18,19 Table 71.1 shows recommendations for assessing the relevant criteria: the ability to communicate a choice, to understand the relevant information, to appreciate the situation and its consequences, and to reason about treatment options. When patients are capable of decision making, they should be involved to the extent that they desire. Patients who have not prepared advance directives should be asked if they would like to prepare such a directive and should be asked to designate someone to hold durable power of attorney for them.

Table 71.1

Legally Relevant Criteria for Decision-Making Capacity and Approaches to Assessment of the Patient

*Responses need not be verbal.

From Appelbaum PS: Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1834-1840.

Collaborative Care

Care in the ICU is provided by a multidisciplinary team; good collaboration among its members is essential. Paying attention to the perspectives of all team members and respecting their skills and clinical judgment are ethically important and are associated with improved clinical outcomes.20 Collaboration is valuable not only for individual patients’ care but also to achieve optimal function of the unit as a whole.21

Justice-Related Issues

Of interest, Baker and Strosberg have argued that the assumption that triage is based on a utilitarian theory of justice is not correct.22 They point out that triage was developed by Larrey, surgeon general of Napoleon’s army, as a strategy for systematically handling the wounded so that those who had to be attended to first got care without regard to rank, in keeping with the French Revolutionary commitment to liberty, equality, and fraternity. Baker and Strosberg suggest that an egalitarian form of triage is advantageous because the public is likely to voluntarily comply with it. Persons with normal “rational self-interest” would agree with it because it improves everyone’s chances of survival. The chances of survival of the fatally wounded and the slightly wounded would not be significantly altered by deferred treatment. This optimal arrangement thus also is compatible with a social contract theory of justice.23

Although triage strategies have relied on the probability of survival, some authors have argued that this is too crude an outcome measure to guide triage. Engelhardt and Rie have suggested that critical decisions to admit, continue care, or discharge patients should be based on a more complete formula that includes probability of successful outcome, quality of life, predicted length of life remaining, and cost of therapy.24

Admission Criteria

The Task Force on Guidelines of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and the American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCM) have published recommendations for ICU admission and discharge.25,26 Each ICU should create a specific policy that explicitly articulates admission and discharge criteria and defines the services that it provides to the population served. Compliance with the policy should be monitored, and the policy should be revised as needed. Any decision to deny a patient admission should be made by clinicians who are familiar with expert opinion and relevant literature and should use established guidelines. Standardized criteria and guidelines facilitate fair rationing because they enhance the likelihood that patients will be treated similarly.

Discharge Criteria

Discharge decisions should be guided by an assessment that less care is necessary and should take patient safety into account. Decisions to transfer a patient from the ICU to other hospital facilities should always be accompanied by good communication with the receiving team to avoid oversights and errors in care.27 Straightforward indications would include, at one extreme, improvement in medical condition that obviates the need for further intensive therapy or, at the other extreme, a decision to end intensive care because of impending death. The ethically challenging aspect of discharge criteria involves the question of discharge when a patient’s probability of survival is expected to be only minimally improved by remaining in the ICU, but the probability is not zero.

Triage

Triage decisions should be made explicitly and without bias. Ethnicity, race, gender, social status, sexual preference, and financial status should not be considered.26 Factors that are appropriate to consider include probability of survival; likely functional outcome; age; chronic underlying conditions; marginal benefit to be gained; and preferences expressed by the patient or surrogate.28 When the ICU is full, patients already in the ICU should not necessarily be given priority if someone else stands to benefit more from the care.29 Like many ethically difficult decisions, triage decisions can be made more manageable by thinking proactively, every day, about the disposition of patients. For example, ICU physicians should regularly review the status of all patients in the unit to assess their degree of readiness for discharge in case the need for new admissions arises.27 Application of this kind of strategy should involve cooperation with other patient care units in the hospital to arrange smooth transfer.

Even when policies are in place for fair triage through an admission approval process by a designated individual, attempts to circumvent admission rules by seeking permission from ICU clinicians or administrators who are on duty in the ICU are fairly common.30 Therefore, policies should be designed to anticipate—and resist—such backdoor efforts.

In addition to decisions about admission, discharge, and triage, ICU physicians frequently must deal with the question of whether to offer or withhold treatments from patients with ultimately fatal injuries or illnesses. The ethical reasoning behind decisions to ration possibly beneficial interventions should be clear in the clinician’s mind31; this issue is discussed more fully later in the section on termination of medical care.

Because expected benefit is a crucial factor in decision making, it is important for critical care physicians to understand the limits of prognostic guidelines for patients with life-threatening illnesses.32 Physicians should recognize the degree of uncertainty that surrounds mortality estimates. Although it is useful to consider a patient’s expected outcome, and to use this prognosis to guide decisions, a false sense of certainty can lead to mistakes. Furthermore, communicating prognostic information with a false sense of certainty can lead to misunderstanding and subsequent distrust on the part of families. Prognostic scoring systems can serve as a useful baseline on which to build treatment recommendations, but firm thresholds should not be set. For a patient with a very uncertain prognosis, trying different treatments for short periods can avoid extended inappropriate treatments without denying care that has a minute chance of working. Medical decision making requires more than functional assessment and prediction. Scoring systems can provide an unbiased measure to help inform physicians’ decisions, but such measures should not be adopted as absolute guides.32

Disparity in Use and Outcome of Intensive Care

Critical care clinicians should be aware that a number of studies show a pattern of disparity in use of intensive care that is the result of forces outside the ICU itself. Patients of lower socioeconomic status have higher mortality rates.33 Patients who lack health insurance are less likely to be admitted to hospitals; once hospitalized, however, they are more likely to be admitted to the ICU and more likely to die in the hospital.34 Patients with private attending physicians are likely to stay longer in the ICU. Intensive care providers should try to prevent inequitable use of resources in the delivery of critical care services.

The Ethics of End-of-Life Care

Defining Death

Given the emphasis on life and death decisions in intensive care, it is prudent for the critical care practitioners to be aware of the many philosophical questions surrounding the definition of death.36 In any consideration of the definition of death, it is useful to recognize that death is more of a process than an instantaneous event and that the boundary between life and death is not perfectly sharp. The specification of any standard will require some arbitrary line drawing that has ethical implications.36

In 1968, the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death determined that severely brain injured patients meeting certain diagnostic criteria could be declared dead prior to the cessation of cardiopulmonary function.37 The use of neurologic criteria to determine death was subsequently accepted by some states in the United States. However, confusion remained with regard to what constituted “brain death”; specifically whether total brain nonfunction or brainstem nonfunction sufficiently fulfilled neurologic criteria for death. In response to the variability in state statutes regarding brain death, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine published a uniform statute for determining brain death, called the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA). According to the UDDA, “an individual who has sustained either 1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory function or 2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem is dead. A determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.”38

The ethical justification for using neurologic criteria to determine death relies on the presumption that in brain death, the body of the patient is no longer “a somatically integrated whole” and that in the absence of whole brain function, maintaining circulation, even with cardiorespiratory support, will stop imminently within a defined period of time.39

Recently the use of brain death criteria has been questioned in the medical and bioethical community. Opponents of using brain death criteria cite the uncertainty in determining physiologic death by neurologic parameters. There is evidence that even in the setting of whole brain death many homeostatic functions can persist, including maintenance of body temperature, wound healing, the gestation of a fetus in a pregnant patient, and sexual maturation and growth in pediatric patients who fulfill the neurologic criteria for death.40 In addition, cardiopulmonary death does not always occur in a timely fashion after brain death and in rare cases may take weeks or years to occur after brain death has been declared.41 Notably, arguments against neurologic standards of death do not preclude the ethical permissibility of withdrawing supportive care when the criteria of brain death have been met, but question whether these criteria alone constitute the death of the patient.

In response to concerns regarding brain death as a legitimate determinant of human death, the President’s Council on Bioethics revisited the philosophical and clinical dilemmas surrounding this issue in 2008.39 The council’s ultimate conclusions were to support neurologic criteria of brain death with an alternative argument regarding defining death as the inability of the organism to function as “a somatically integrated whole.” Rather, “total brain failure” constitutes death as the patient, “is no longer able to carry out the fundamental work of a living organism. Such a patient has lost—and lost irreversibly—a fundamental openness to the surrounding environment as well as the capacity and drive to act on this environment on his or her own behalf . . . a living organism engages in self-sustaining, need-driven activities critical to and constitutive of its commerce with the surrounding world. These activities are authentic signs of active ongoing life. When these signs are absent, and these activities have ceased, then a judgment that the organism as a whole has died can be made with confidence.”

Currently all 50 states and the District of Columbia have adopted the UDDA definition of brain death by statute or judicial decision. Two states, New Jersey and New York, have specific laws or regulations to address religious objections to neurologically based declarations of death.42 Similarly, over 90 countries use neurologic criteria to determine death in addition to traditional cardiopulmonary criteria.43 The cultural variability in accepting neurologic criteria to determine brain death is exemplified in the organ transplant laws in China and Japan. In 2003, the Chinese Ministry of Public Health drafted a proposal to outline neurologic criteria that would define death in the absence of cardiopulmonary arrest. However, legislation approving the use of brain death criteria was not endorsed, lacking support from the public and health care professionals.43 Prior to 2010, Japan’s Organ Transplant Law only recognized brain death when the patient had given prior written consent to be an organ donor and the family did not object to the donation. This law has since been revised to allow a determination of death based on neurologic criteria for the purposes of organ donation with family consent so long as the donor did not previously refuse organ donation. However, the revision still does not address whether neurologic criteria for death are sufficient in the absence of an anticipated organ donation.44

Withholding and Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Treatment

The first suggestion that physicians should withhold medical interventions from terminally ill patients probably dates to Hippocrates’s injunction to “refuse to treat those [patients] who are overmastered by their disease, realizing that in such cases medicine is powerless.”45 In 1835, Jacob Bigelow urged members of the Massachusetts Medical Society to withhold “therapies”—such as cathartics and emetics—from hopelessly ill patients.46 In 1848, John Warren, the surgeon who performed the first operation with ether anesthesia, urged that ether should be used “in mitigating the agonies of death.”47 In 1958, Pope Pius XII, in response to questions about resuscitating patients and maintaining comatose patients on respirators, stated that physicians had no obligation to use such “extraordinary” means to forestall death.48 The concept that the mere extension of life is not always in the best interest of the patient is perhaps even more apparent in current times, when advances in medical technology have led to the seemingly indefinite prolongation of the lives of the critically and terminally ill.49

Many physicians find withdrawing life-sustaining treatment more difficult than withholding treatment. However, from a bioethical perspective, there is little distinction between withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatments.50 Competent patients have the right to refuse medical care and can use whatever criteria they deem acceptable; it is their values that guide the choice.51 Every medical intervention, including artificial nutrition and hydration, may be terminated under some conditions.

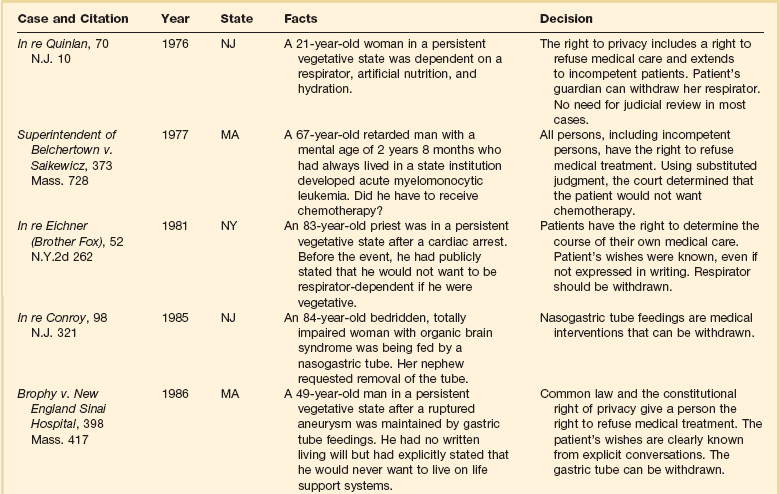

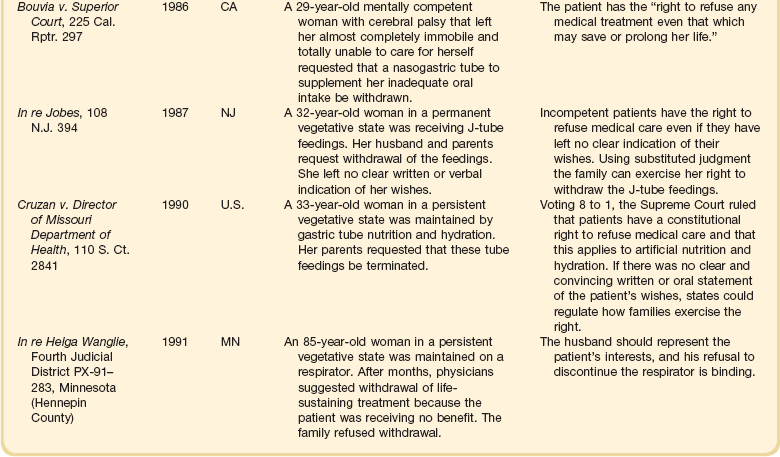

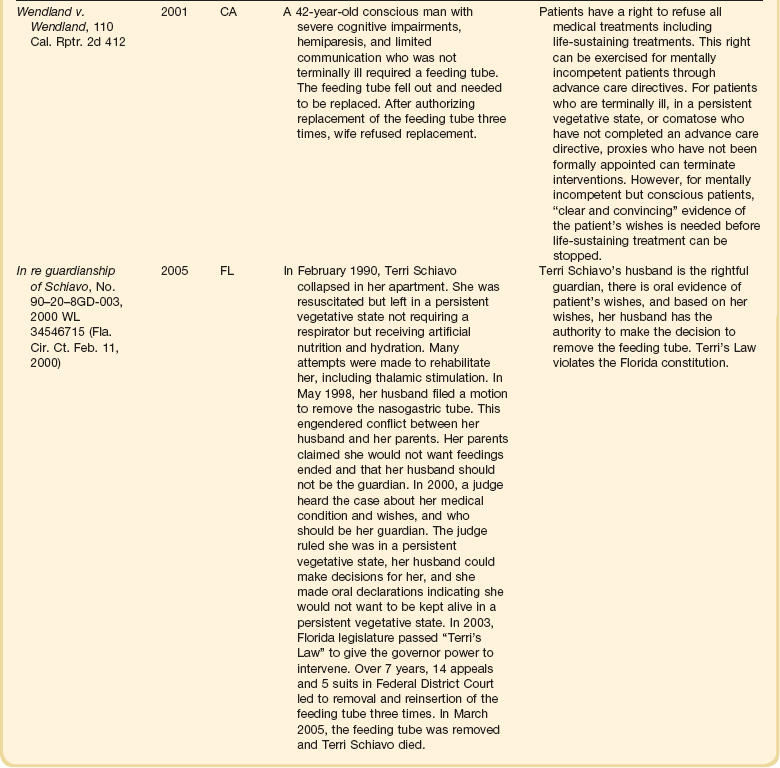

The right to refuse medical interventions, including life-sustaining treatment, is supported by legal precedent (Table 71.2). Court decisions have sanctioned the withholding or withdrawal of respirators, chemotherapy, blood transfusions, hemodialysis, and major surgical operations. In its 1990 Cruzan decision, the U.S. Supreme Court recognized that competent patients have a constitutional right to refuse medical care.52

Competent patients need not be terminally ill to exercise the right to refuse interventions; they have the right regardless of health status. Moreover, the right applies both to withholding proposed treatments and to discontinuing initiated treatments. This does not, however, imply that patients have a correlative right to demand treatment.53,54

In theory, the right of patients to refuse medical therapy can be limited by state interests in the preservation of life, prevention of suicide, protection of third parties such as children, and preservation of the integrity of the medical profession.54 In practice, these interests almost never override the rights of competent patients or of incapacitated patients who have left explicit advance directives.

Advance Care Directives and Durable Powers of Attorney

There are two types of advance care planning documents: living wills and proxy statements. Living wills or instructional directives are advisory documents specifying the patient’s preferences to specific care decisions. State-specific forms that people can fill in to draw up advance directives are available on the Internet.55 Some advance directives, such as the Medical Directive, enumerate different scenarios and interventions for the patient to choose from.56 Among these, some are for general use and others are designed for use by patients with a specific disease, such as cancer.57 Less specific directives can be general statements of not wanting life-sustaining interventions or forms that describe the values that should guide specific terminal care decisions. Of importance, a person does not have to use a state-specific form because “a living will or health care power of attorney that does not strictly follow the statutory [state] form is also valid in most states” and the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that a person has a constitutional right to refuse medical treatments.58 Practitioners should be aware that living wills may have some legal limitations. For instance, in 25 states, a living will is not valid if a woman is pregnant; specific state statutes should be reviewed in caring for a pregnant patient.

The health care proxy statement, sometimes called a durable power of attorney for health care, specifies a person selected by the patient to make decisions. A combined directive includes both instructions and the designation of a proxy; the directive should clearly indicate whether the specified patient preferences or the proxy’s choice should take precedence if they conflict.56

Many states permit clear and explicit verbal statements to be legally binding even if not written down.58 However, such statements must be very explicit. In the Wendland case, a 42-year-old man suffered permanent brain damage and hemiparesis in a car accident.59 The California Supreme Court ruled that when the patient is conscious and there is no advance care directive, there must be “clear and convincing” evidence of the patient’s view in order to permit withdrawal of a feeding tube.59 “Clear and convincing” evidence requires prior comments to refer to the specific intervention in the specific circumstances of the patient, not a similar health state.

In 1984, California passed the first law recognizing the appointment of a designated proxy for health care decisions; by 2007, all 50 states and the District of Columbia had enacted statutes recognizing the durable power of attorney for health care decisions. There are some limitations. For instance, although most states permit proxies to terminate life-sustaining treatments, Alaska prohibits such decisions by proxies. In other states, orally appointed proxies are limited to a particular hospitalization or episode of illness. Nevertheless, it appears that any properly filled-out, formal advance care document or durable power of attorney designation, whether or not it conforms to a state’s specific document, is protected by the U.S. Constitution and must be honored.52

Although advance directives can be helpful in guiding clinicians and family members, many patients have not prepared them. Despite polling data showing that approximately 80% of Americans endorse the use of advance directives, and passage in 1990 of the federal Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA), which requires hospitals and other health care facilities to inform patients about their right to complete an advance care directive, less than 30% of the adult population in the United States has a formally prepared advance directive.60 The use of advance care directives may be more prevalent in older adults. Silveira and colleagues used data from the Health and Retirement Study to survey the proxies of patients 60 years and older who had died between 2000 and 2006 and found that approximately 47% of these patients had advance directives.61

However, even when advance care directives have been prepared, they frequently are not in the patient’s medical record, and the patient’s physician may not be aware of the existence or content of the document.62,63 In addition, recent studies suggest that most advance directives are either proxy forms or standard living wills, and that few have any specific directions from the patient.64 Finally, studies confirm that proxies and family members tend to be poorly informed about patients’ wishes regarding end-of-life care and therefore are unlikely to make decisions as the patient would.65,66 Even if specific treatment courses are outlined, these directives may be outdated as preferences change with time or the patient’s medical condition evolves. Ideally, advance directives should be revisited with the patient over time with family members or a physician with whom the patient has a long-term relationship.

Futile Treatments

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, some argued that physicians could ethically terminate futile treatments.67 However, citing medial futility as an ethical and legal justification for the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments is not a clear-cut endeavor and has been criticized as inadvisable.68,69 The term futility carries both quantitative and qualitative meanings. There is little, if any, agreement among health care professionals as to what numeric threshold of probability should be considered an indication of futility. Medical futility also has a qualitative aspect that implies that the objective of the proposed treatment is not worthwhile.42 The qualitative definition of futility can be especially problematic when patients or their surrogate decision makers disagree with physicians about what constitutes a worthwhile outcome. In addition, a declaration by clinicians that a treatment is futile can marginalize patients and surrogates by effectively revoking their participation in treatment decisions. Thus, the ambiguities in defining medical futility and the potential for alienation of patients and family members have led some bioethicists to propose that the term futility be replaced by the terms “medically inappropriate” or “surgically inappropriate” to more accurately describe an assessment that reflects a professional opinion rather than a summation of value.70

Nonetheless, some states including Texas, Virginia, Maryland, and California have enacted so-called medical futility laws.71 These laws protect physicians from liability if they terminate life-sustaining treatments against family wishes. In Texas, if the medical team and the hospital ethics committee believe that interventions should be terminated, but the patient’s family disagrees, the hospital is supposed to seek another institution willing to provide treatment.71 If, after 10 days, this fails, then the hospital and the physician may unilaterally withdraw treatments determined to be futile; however, the family may appeal to a state court. Early data suggest that the law increases futility consultations with the ethics committee, and that most families concur with withdrawal decision.71

Some hospitals have enacted “unilateral DNR” (do not resuscitate) policies to allow clinicians to provide a DNR order in cases in which consensus cannot be reached with families and there is medical opinion that resuscitation would not affect a patient’s outcome. Because the ethical justification for unilateral DNR relies on the medical assessment that resuscitation efforts will not achieve the desired outcome (i.e., resuscitation is futile) the unilateral DNR remains a controversial policy. If a unilateral DNR is being considered by a physician, a second opinion by another physician and a hospital ethics committee consultation should be considered.42

“Partial codes” and “slow codes” describe resuscitation efforts that are selective or foreshortened in the setting in which the medical team believes resuscitation efforts to be inappropriate and the patient’s family or proxy will not agree to a recommended DNR order. Slow codes have been historically almost universally repudiated in the bioethics community. The American College of Physicians Ethics Manual cautions against slow codes as “deceptive, half-hearted resuscitation efforts.”72 Ultimately slow and partial codes threaten the ethical principles of autonomy and beneficence. By neither attempting a full resuscitation nor invoking a unilateral DNR, the patient’s or surrogate’s decision is disregarded while administering a nonbeneficial treatment. However, more recently Lantos and Meadow have defended the practice of partial and slow codes when communication has been exhausted and intractable disagreements about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) persist.73–75 Supporters of the slow or partial code cite the symbolic value of CPR and delineate specific circumstances in which such a limited code would be ethically permissible such as when resuscitation will almost certainly be ineffective, the surrogate decision makers understand that death is inevitable, and the surrogates “cannot bring themselves to agree to a do-not-resuscitate order.”73 When compared to enforcing a unilateral DNR on a surrogate or family member, such a compromise may be a more compassionate option for those responsible for making a decision on DNR status. However, arguments supporting limited resuscitation are almost always focused exclusively on the welfare of the surrogates, rather than the patient under the physician’s care. Therefore, slow and partial codes should not be considered an acceptable practice in the care of critically ill patients.

Ordinary/Extraordinary Care

Following Pope Pius XII’s and Roman Catholic teachings, some ethicists advocate a distinction between ordinary and extraordinary care: Ordinary care is considered to be mandatory, whereas extraordinary care may be withheld or withdrawn.48 One commentator for the Catholic Hospital Association explained this distinction as follows:

Ordinary means of preserving life are all medicines, treatments, and operations, which offer a reasonable hope of benefit for the patient and which can be obtained and used without excessive expense, pain, or inconvenience. . . . Extraordinary means of preserving life mean all medicines, treatments, and operations, which cannot be obtained without excessive expense, pain, or other inconvenience, or which, if used, would not offer reasonable hope of benefit.76

Many ethicists and courts have concluded that this distinction is too vague and has “too many conflicting meanings” to be helpful in guiding surrogate decision makers and physicians.53,54,77,78 As one lawyer noted, ordinary and extraordinary are “extremely fact-sensitive, relative terms. . . . What is ordinary for one patient under particular circumstances may be extraordinary for the same patient under different circumstances, or for a different patient under the same circumstances.”78 Thus, the ordinary versus extraordinary distinction should not be used to justify decisions about stopping treatment.54

Substituted Judgment

The standard of substituted judgment is based on preserving the patient’s right of self-determination in the absence of decisional capacity. Many courts advocate use of the substituted judgment criterion. Substituted judgment holds that the surrogate decision maker should try to imagine what the patient would do if the patient were competent.77 That is, the surrogate should try to “ascertain the incompetent person’s actual interests and preferences” and to make the decision that “would be made by the incompetent person, if that person were competent.”79

In the absence of specific guidance from the patient, substituted judgment involves surmising what a patient would want, rather than a guaranteed fulfillment of the patient’s wishes.54,80 Of note, patients who were surveyed varied regarding the extent to which they want families to strictly adhere to their personal wishes in making end-of-life decisions on their behalf.81

Best Interests

The best-interests criterion holds that treatment decisions should be made based on balancing benefits and risks and should select those treatments in which the benefits maximally outweigh the burdens of treatment.53,54 When the patient’s wishes are truly unknown or cannot be inferred, the best-interests standard should take precedent.

For the best-interests standard to work, there must be some “objective, societally shared criteria” about what constitutes benefits and burdens.82 However, as is made clear by many court cases involving conflict between family members, or between family members and the medical team, no objective way of determining benefits and burdens, and how they should be balanced, has been recognized. One court suggested that burdens should be determined solely by levels of pain.53 However, many people consider a permanent vegetative state to be a serious burden that they want to avoid, even if they do not feel pain. In the absence of an objective best-interests standard, families largely decide what constitutes a benefit or burden from their estimation of a patient’s personal values.

Ethical Issues in Transitioning Patients to Palliative Care

Critical care clinicians have a particularly challenging responsibility when taking care of patients whose chances of survival are uncertain. Under such circumstances, clinicians need to understand how to use prediction tools such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) tool or the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) system, or SAPS II, to estimate the likelihood of survival. Awareness of the limited predictive ability of these tools is important for the ICU physician, who at the same time will use them to trigger decisions and interventions as part of a systematic approach to improving care.83

Although prognosis is uncertain, clinicians are advised to attend to the dual goals of prolonging life and palliating symptoms. As a patient’s prognosis becomes increasingly worse, consideration needs to be given to withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatments. Useful guidelines for withdrawing life support are shown in Box 71.3.

Because decisions to limit life support should be shared with patients or their families, clinicians should be familiar with the important components of discussing these decisions. These components are summarized in Box 71.4.

Critically ill patients require relief of symptoms regardless of their prognosis. Once a patient is thought to be dying, the focus of care increasingly shifts away from combined efforts to prolong life and palliate symptoms to more exclusive focus on palliative care. Critical care clinicians should aim to deliver high-quality palliative care (Box 71.5).

When the decision is made to withdraw treatment and focus on comfort care, necessary palliative interventions to relieve pain, alleviate air hunger, or assuage anxiety may cause the unintended effect of hastening death. The doctrine of double effect provides the ethical justification for providing care that may have harmful effects. This principle relies on the distinction between an intended versus a foreseen but unintended effect of treatment50. There are a number of critics of this doctrine84; some opponents of the doctrine of double effect deny that the distinction between intended and merely foreseen consequences has moral significance. Regardless of whether one relies on this doctrine, most clinicians and medical ethicists endorse the view that if the goals of care have shifted to alleviating symptoms of pain and discomfort, administering interventions to achieve these goals is ethically and legally permissible even if doing so results in hastening the patient’s death.

Palliative Sedation

Palliative sedation is a controversial practice in part due to the lack of a consistent definition. Administering sedatives to a dying patient in a titrated fashion for the purposes of specific symptom relief is an accepted practice in palliative care. However, the term palliative sedation has also been used to describe the practice of providing continuous sedation to the dying patient for the purposes of maintaining a sustained level of unconsciousness. In 2008, the American Medical Association (AMA) condoned the use of palliative sedation to unconsciousness to relieve intractable clinical symptoms unresponsive to “aggressive symptom-specific treatments.” A palliative care team should be consulted to ensure that all other treatment options have been exhausted. Informed consent must be obtained from the patient or the patient’s surrogate. Obtaining consent should include a thorough discussion addressing the degree and length of sedation with respect to achieving an intermittent or constant level of unconsciousness. The AMA Code of Ethics does not condone the use of palliative sedation to unconsciousness for the purposes of relieving existential suffering such as feelings of death anxiety, social isolation, or loss of control, citing that these symptoms are more appropriately and effectively addressed by alternative measures.85 Other professional organizations including the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) and the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) have released similar policy statements and recommendations and additionally recommend an interdisciplinary approach involving palliative care expertise.86,87 The NHPCO recognized the controversy surrounding palliative sedation to unconsciousness for relief of existential suffering and the panel was unable to reach an agreement on recommendations regarding this practice.86

Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide

Administering treatments to hasten death as a way to relieve pain and discomfort falls into the realm of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. The term euthanasia requires clarification. So-called passive euthanasia is the withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining medical interventions and is widely accepted as both ethical and legal. “Indirect euthanasia”—such as increasing narcotic dosage to ease a patient’s pain, even if this has the consequence of hastening the patient’s death—also is a misnomer; it generally has been deemed both ethical and legal for more than 100 years.88 Almost all commentators agree that involuntary and nonvoluntary active euthanasia are unethical because they end the life of a patient without consent. Consequently, the focus of debate is on physician-assisted suicide and voluntary, active euthanasia. To avoid confusion, use of the term euthanasia should be restricted to voluntary, active euthanasia.

Proponents typically cite four reasons to justify physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia.88,89 First, they claim that euthanasia ensures patients’ autonomy. How a person dies is essential to that person’s values. Therefore, to respect patients’ autonomy, it is mandatory to respect their wishes regarding the manner and timing of their death, through euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide.90,91 Second, for some patients, dying causes pain and suffering. A main purpose of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide is a comfortable, quick death. Hence, euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide furthers beneficence, which is one of the major principles of medical ethics.90,91 Third, euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide are morally equivalent to terminating life-sustaining treatments. The goal is the same: a peaceful, painless death. Furthermore, there is no difference between an act of omission and an act of commission.91 Finally, the potential adverse consequences of legalization are speculative.

Opponents of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide offer four parallel but opposite arguments. First, autonomy does not justify euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide.92–94 Autonomy does not mean a person should be permitted to do anything he or she wishes. Both Kant94a and Mill94b thought that a person’s autonomy could be limited to prevent voluntary dueling or slavery. Similarly, one could argue that because euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide are aimed at ending autonomy, they can be limited without infringing autonomy. Second, many terminally ill patients receive inadequate treatment for pain, fatigue, and depression. With proper treatment, few people would experience pain and suffering of a level sufficient to justify euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide. Third, acts of omission and acts of commission are not equivalent. The ethical validity of an act does not depend solely on its final result but also stems from the intention of the person performing it. When physicians stop a medical intervention, they are stopping unwanted bodily intrusion, not trying to end a person’s life; euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide do aim to end a person’s life.38,92–94 Finally, permitting euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide would have a variety of well-documented adverse consequences. These effects include disruption of the doctor-patient relationship, intrusion of the courts, and possibly extension of euthanasia to children, mentally incapacitated patients, and others.94

Although the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld the right of patients to reject medical treatment, the Court ruled unanimously in 1997 that there is no constitutional right to euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide.95 Of importance, the U.S. Supreme Court did permit individual states to legalize these interventions. Oregon and Washington state have enacted legislation permitting physician-assisted suicide.96,97 The Supreme Court of the state of Montana has ruled that prohibition of physician-assisted suicide is against the state’s constitution.98

The Netherlands and Belgium have legalized both euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Their legislation included the following safeguards: The patient must have unbearable pain and suffering that cannot be medically relieved; the patient must be competent and must repeatedly request to have his or her life ended; and the physician must consult a second physician.99 In 2008, Luxembourg legalized euthanasia for patients with a “grave and incurable” condition. The physician must first consult a colleague and the patient must have repeatedly asked for the intervention.100

For a brief period the Northern Territory of Australia had legalized euthanasia, but this was rescinded by the national legislature.101 In Switzerland assisted suicide is legal and the assistance need not be provided by a physician.102

Research in Critically Ill Patients

History and Fundamentals of Human Research Ethics

Among the first documented experiments with human subjects were vaccination trials in the 1700s. In these early trials, many physicians used themselves or their family members as test subjects. Even these early practices were not without some formulations of research ethics. In 1865, the French physiologist Claude Bernard wrote that the first principle of medical morality “consists in never performing on man an experiment which might be harmful to him to any extent, even though the result might be highly advantageous to science.”103 Louis Pasteur is reported to have “agonized” over performing a previously untried intervention in humans, even though he was confident of the results obtained through animal trials. He finally did so only when he was convinced that the death of the first test subject “appeared inevitable.”104

In the twentieth century, the medical experiments conducted by German physicians on concentration camp prisoners during World War II ushered in a new era of research ethics. After the war, 23 Nazi doctors and scientists were put on trial at Nuremberg for the torture and murder of concentration camp inmates who were used as research subjects. Most were convicted and sentenced to death or prison terms ranging from 10 years to life.105

The Nuremberg judges were convinced that the Hippocratic Oath alone could not serve as an adequate foundation for ethical research. Accordingly, their principles for research, which became known as the Nuremberg Code, were meant to protect subject welfare as well as basic human rights.106,107 They formed the basis of the research ethics codes that are used internationally today.

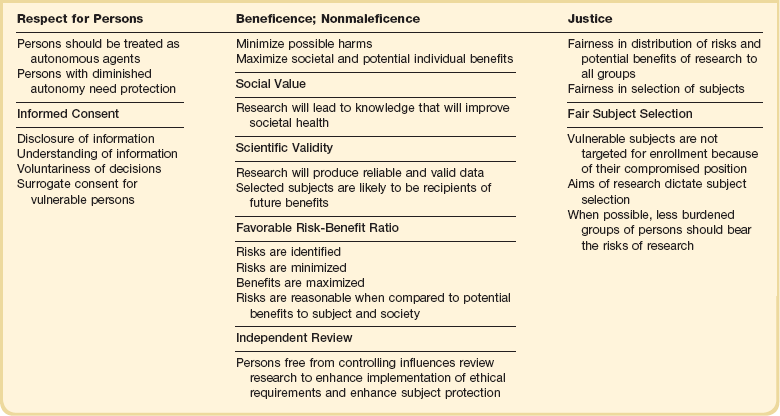

In the United States, the fundamental ethical guidelines for medical research were set out in 1974 by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects in Biomedical and Behavioral Research, which was established by Congress after a series of ethical scandals in the 1960s and 1970s. In its Belmont Report, the Commission outlined three basic ethical principles for the conduct of medical research: respect for persons; beneficence; and justice108 (Table 71.3).

Putting Principles into Practice: Applications

Although ethics codes and regulations exist to ensure the ethical conduct of research, what is needed is a systematic and coherent framework for evaluating the ethics of human subject research that incorporates all relevant ethical considerations. Stemming from the principles of research ethics, several requirements have been proposed to ensure the ethical conduct of research set out in the Belmont Report (see Table 71.3).

Scientific Validity

The ideal clinical trial establishes whether therapeutic interventions work and determines the overall benefits and risks of each alternative. This is achieved by limiting the effects of chance, bias, and confounding. The need for scientific rigor also must be balanced against other requirements of clinical trials, such as protection of subjects’ rights and welfare as well as minimizing the cost and the number of subjects necessary for enrollment to achieve significant results.109

An important ethical construct in clinical trials is that of clinical equipoise.110 This concept refers to the existence of an “honest, professional disagreement among expert clinicians” concerning the relative benefits and harms of the interventions being tested.110 The presence of clinical equipoise serves two important goals.111 It assures a physician that random selection of the intervention that a research participant will receive is ethically permissible, as neither of the interventions in the study groups dominates the other in terms of perceived safety and efficacy. Accordingly, the welfare of research subjects is not knowingly sacrificed for the interests of future patients. The other goal ensures that the results of the research will disturb clinical equipoise and hence yield reliable, generalizable information regarding the standard of care. The randomized controlled trial (RCT) is a formal method of resolving uncertainty about scientific knowledge, although well-conducted observational cohort and case-control studies also can provide valuable information to disturb equipoise and might lead to better human subject protections.112,113 Several research methods have raised specific ethical issues in critical care research and deserve special mention. Some examples follow.

Placebo Controls

Clinical research involving placebo controls in circumstances in which an established therapeutic alternative is not available is not ethically problematic. In this situation, an experimental intervention (e.g., a new drug) is compared with a placebo and both may be superimposed on the current standard of care for the enrolled research participants. Placebo controls have been used in trials of critical care treatments for a wide range of conditions, including asthma and pulmonary hypertension.114,115

In contrast, the use of a placebo control group, when a proven effective treatment exists for the medical condition, does raise ethical issues. Critics of placebo-controlled trials contend that when effective treatments exist, placing patients in a placebo group is not only unethical but also unwise. They argue that no scientific or clinical value derives from determining whether an investigational drug is better than an inert placebo; instead, they say, an experimental treatment should be compared with a standard treatment, to demonstrate which is better.116,117

Advocates of placebo-controlled studies argue that such studies are not only ethical but indeed necessary under many circumstances.118–120 For example, an experimental therapy may have fewer side effects or may be more effective for particular subgroups of patients, but these effects might not be recognized in active-control trials. Moreover, demonstrating that a new treatment is equivalent to an existing treatment may not prove that the new treatment is effective; both treatments could be ineffective. And comparing an experimental treatment with an existing treatment would require many more patients in each arm of the study than are necessary for a placebo-controlled trial.

Choice of Control in Clinical Trials Comparing a New Intervention with the Current Standard of Care

If a new intervention is going to be compared to contemporary standard practice the control must be representative of current practices both to permit a useful comparison and to protect the welfare of research participants, as the inclusion of such a control group allows a trial to be stopped early if the tested intervention has a mortality rate or survival rate that is significantly higher than standard practices.121

The difficulty in control group selection is made more manifest when current practices of critical care practitioners are variable. Accordingly, the choice of control group may involve a set protocol that is designated as the standard of care, and there are constraints on all treatment in both the experimental and standard-of-care control groups. Such constraints serve to improve the signal-to-noise ratio and increase the likelihood of finding difference between the tested interventions.122 However, the cost of using such control groups that enhance scientific validity is reduced generalizability and a potential to increase the risk of harm to enrolled research subjects.109,122,123

In recognition of this concern, several critical care trials have used so-called ”usual care” control groups whereby the control group represents the broad range of current practices and care is individualized for each patient. Several important critical care studies,124–128 including those involving mechanical ventilation,129–131 have proved to be extremely informative.132 Surveys and observational studies of clinicians’ practice patterns would help ensure that such control groups reflect usual care. An international trial evaluating two target ranges for glycemic control in ICU patients took such an approach.133

Informed Consent

Informed consent is the ethical prerequisite for all clinical trials involving human beings. The informed consent process respects subjects’ autonomy and ensures that they are not to be used merely as a means to another’s end.134 It also provides research subjects a mechanism to protect themselves.135,136 Practices regarding obtaining informed consent from critically ill patients differ among researchers; for example, there is a difference in the extent to which participants consent personally rather than having a surrogate do so.137

Valid informed consent consists of three major elements: disclosure of information, subject competence to make a decision, and voluntariness of the decision.138

Disclosure of Information

The basic elements of information that should be communicated to potential subjects and their surrogates include a full description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts a subject may experience, and full disclosure of other procedures or courses of treatment that are available139,140 (Box 71.6). Some of these elements are absent in many informed consent forms, including those used in critical care clinical trials.141,142 Recommendations for writing informed consent forms for critical care studies have been published.143

Decision-Making Capacity

Critical care investigators face a difficult task of recruiting research subjects who may have diminished capacity to give valid informed consent. Patients with acute illnesses often have limitations in their decision-making capabilities due to a number of factors, including the presence of delirium, their underlying illness, or the use of sedatives and analgesics.144–146 Understanding is less complete in severely ill patients than in healthier patients.147 Research participants enrolled in clinical trials often have limited understanding of the research to which they have consented.148,149 Many potential participants may not understand certain concepts of randomization, the notion of a placebo design, research risks, and the distinction between research and clinical care. Understanding is less complete in severely ill patients than in healthier patients.147 Investigators should make special efforts to ensure that potential research participants understand these general concepts and their implications for the specific study participants may be consenting to.

Investigators also should keep in mind that written descriptions of the research may not be effective in conveying information—particularly if the written material is so long and technical that potential research participants do not read it fully. Information given verbally can enhance understanding by giving research participants the opportunity to engage in a dialogue with the investigator. The opportunity for such a dialogue for patients receiving ventilatory support is difficult, and hence, the feasibility of enrolling such individuals with their own informed consent might be ethically problematic. One approach to such potential research participants who have some degree of decisional capacity is to obtain their assent in conjunction with proxy consent.137

Regarding the distinction between research and clinical care, patients and families have a strong tendency to inaccurately attribute therapeutic intent to the research.150 Physician-investigators should explicitly refute such a “therapeutic misconception” and should dispel any notion that a clinical trial is designed to or will provide patients with direct benefits, or that the research substitutes for clinical care.108,151

Finally, the research community often assumes that research participants derive benefits solely from participating in a research study—even if they are receiving inert placebo—because of the extra monitoring and superior care associated with academic “centers of excellence.” Such an “inclusion benefit,” however, has not been proved.152,153

Voluntariness

Valid informed consent requires that patients’ decisions to enroll in clinical trials are free from coercion—including a fear, justified or not, that they may be harmed in some way if they do not enroll in the clinical trial.108 The institutional setting of the research may be a source of subtle or covert coercion. Critically ill patients often lack decisional capacity. Patients may feel they have little choice but to participate in research when “their doctor” asks them to do so—particularly if their treating physician occupies the dual role of clinician-investigator. Accordingly, someone other than the treating physician should obtain informed consent from patients.154,155

Another factor that may affect voluntariness is the presence of undue influence, which occurs when offers to induce enrollment, such as financial payments or free medical care, are of such magnitude that they influence subjects’ decisions.156

Proxy Consent

Ethically acceptable research may proceed with critically ill patients who are—or are at risk of becoming—decisionally impaired, if the investigators receive appropriate proxy consent.157,158 U.S. and European standards require proxy or surrogate decision makers to be legally authorized to provide such consent. In the United States, the legal representative for the patient is determined by the applicable state laws.

If possible, surrogate decision makers should follow the “substituted judgment” standard: They should make a good-faith judgment of what the subjects would have decided if capable of making a decision themselves. As discussed earlier, however, surrogates often do not know patients’ previous preferences.159,160 Therefore, they also should consider what would be in the best interests of the patient.

Investigators should appreciate that family members of critically ill patients have high levels of anxiety and psychological distress that might impair their ability to give adequate informed consent for research participation for incapacitated patients.161,162

If research participants who were entered into a trial through proxy consent regain decisional capacity during the trial, investigators should obtain their informed consent for continuing their participation.163 Such retrospective consent should be sought even when the research procedures have been completed, because research participants have a right to know that they have participated in a trial and that further data may be collected. Whether participants should be given the right to withdraw the data obtained from them when they were unconscious is an unsettled issue. This is a sound proposal, ethically speaking, but from a methodologic standpoint it is arguable because it could ruin the comparability of study groups.

Waiver of Informed Consent

In some circumstances, the informed consent requirement can be waived—but only when an IRB finds that all of the following conditions are met:139

• The research involves no more than minimal risk to the research participants.

• The waiver or alteration of informed consent requirements will not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the research participants.

• The research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver or alteration.

• Whenever appropriate, the participants will be provided with additional pertinent information after participation.

Under U.S. regulations, research may be characterized as minimal risk if “the probability and magnitude of harms or discomforts anticipated in the research are not greater in and of themselves than those ordinarily encountered in daily life or during the performance of routine physical or psychological examinations or tests.”164 In other words, the types of minimal risks that are considered socially acceptable, such as in driving to work or crossing a street, or those encountered in routine physical or psychological evaluations, are acceptable in research.

An IRB can grant a waiver of informed consent for research assessing interventions in medical conditions that frequently occur in emergency situations such as cardiac arrest, stroke, shock, severe arrhythmias, and life-threatening traumatic injury. Patients with these conditions cannot give consent, and the narrow time window in which treatment must be given often does not afford sufficient time to obtain consent from a legal representative. A trial assessing the safety and efficacy of an infusion of low-dose steroid in severe septic shock provides a good example.165

Various countries and regions have differing regulations governing such research. In 1996, the U.S. government specified several mechanisms under which research involving incapacitated research participants in emergency situations can be allowed without informed consent of a legally authorized representative.166 But these procedures have been criticized as unnecessarily complicated and burdensome.167–169

A European Directive regarding clinical research involving drugs contains no provisions for waiver of informed consent for research in emergencies. Some European countries, however, provide for possible waivers in their own regulations.170

Australia’s National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Research Involving Humans allows an ethics committee to approve research without prior consent provided that (1) inclusion in the research is not contrary to the interest of the patient; (2) the research is intended to be therapeutic, and the research intervention poses no more risk than that inherent in the patient’s condition and alternative methods of treatment; (3) the research is based on valid scientific hypotheses that support a reasonable possibility of benefit over standard care; and (4) as soon as reasonably possible, the patient or the patient’s relatives or legal representatives, or both, will be informed of the patient’s inclusion in the research and of the option to withdraw from the research without any reduction in quality of care.171

Regulations in Canada stipulate that research in the emergency setting may proceed under the following conditions: if a serious threat to the prospective subject requires immediate intervention,172 if no standard efficacious care exists or the research offers a real possibility of direct benefit to the subject in comparison with standard care, or if the risk of harm is not greater than that involved in standard efficacious care or is clearly justified by direct benefit to the subject.

Analysis of Risks and Benefits

The U.S. federal regulations require that risks to research participants are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, to the research participants, and the importance of the knowledge that may reasonably be expected to result. This assessment of the potential risks involves three steps.157 First, the risks and discomforts of the trial must be identified; these factors include not only the physical risks but also psychological, economic, and social risks, including those that might emanate from breaches of confidentiality. Second, the risks must be minimized by changing the study design if possible—for example, excluding research participants who are at substantially higher risk, replacing invasive procedures with less risky procedures, or providing enhanced safety monitoring, for example, additional blood studies to monitor for safety. Finally, the risks must be reasonable when weighed against potential benefits to the research participants and to society. In weighing risks and benefits, some ethicists have found it useful to use a component analysis, which distinguishes between procedures with potential for benefiting research participants and procedures that merely answer a scientific question, without offering a potential direct benefit to research participants.158,173

A component analysis is intended to avoid what has been termed the “fallacy of the package deal” in which the potential benefits of one intervention are considered to justify the risks of a another intervention in the study.174

Justifying risks by the separate components of the study does not imply that there is no upper limit to acceptable risk.175 However, what the risk threshold should be is debatable. When investigational procedures do not offer a prospect of direct benefit to the patient, commentators have argued that the risk should be capped at the level of minimal risk.176,177 This position reflects the concern that vulnerable subjects should not be put at undue risk for the sake of society and that such research is exploitative. However, advocating such a risk ceiling would seriously impair important research. Instead of restricting such research, a desirable alternative might be to institute a safeguard for this risk level, such as the “necessity requirement.” Such a safeguard would provide that decisionally impaired research participants can be enrolled in research only when their participation is scientifically necessary—for example, when the desired information cannot be obtained by enrolling adults who can consent. To provide supplemental protection, some guidelines reinforce the necessity requirement with a “subject condition” requirement, under which the research must involve a condition from which the subject suffers.

Core Safeguards for Vulnerable Subjects

Although the U.S. regulations are silent regarding specific safeguards to provide additional protections to adults unable to provide consent, other guidelines have proposed examples of specific safeguards.178 These safeguards include (1) assessment of potential research participants’ decision-making capacity; (2) respect for potential participants’ assent and dissent; (3) “necessity” requirement to ensure that research cannot be performed without enrolling incapacitated adults; (4) “subject-condition” requirement, whereby the research involves a condition from which the subject suffers; (5) an independent participation monitor to monitor participants’ involvement as they progress through the study protocol; and (6) an independent and (7) sufficient evidence of subjects’ prior preferences and interests.

Additional protections for vulnerable people and groups should be based on the level of risk of the procedures that will be involved.172,175,179 For example, for research involving potential direct benefits that pose more than minimal risk, additional protections for vulnerable subjects could include designating independent monitors to witness the informed consent process or to determine when it might be appropriate to withdraw the subject from the study.177,180

Monitoring for Safety of Research Participants

The welfare of participants in clinical trials is overseen not just by IRBs and research ethics committees, which approve protocols before a trial can begin, but also by data and safety monitoring boards (DSMBs), which monitor data from ongoing trials, particularly large, multicenter trials.181 The role of DSMBs is to collect data that otherwise might not be aggregated until much later in a trial and to watch for unexpected adverse results that might necessitate halting the trial—or unexpected beneficial results that might justify making the experimental therapy more widely available.

Research in the International Context

In September 2011, the U.S. Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues published a review of U.S. Public Health Service-led studies in Guatemala involving the intentional exposure and infection of vulnerable populations that occurred between 1946 and 1948 during the study of penicillin to prevent and treat infection. The Commission concluded that “the experiments involved gross ethical violations.”182

The Commission reviewed domestic and international contemporary human subjects protection rules and standards to ensure that federally funded scientific studies are conducted ethically.183 This review was relevant as an increasing number of federally sponsored and pharmaceutical sponsored research is being performed in the developing world. Furthermore, commentators have recommended collaborations with colleagues in the developing world to address global disparities in critical illness and to care for those who become critically ill due to the consequences of natural disasters, acts of war, pandemics, and bioterrorism. Investigators and sponsors of such research need to ensure that it is not exploitative of the indigenous populations and is culturally sensitive.

Collection and Storage of Tissue Samples for Future Unspecified Research, Particularly Genetic Research

Recent advances in genetics, molecular biology, and biomedical technologies have increased the scientific value of research on stored biologic samples and have spurred the development of genetic databases and biobanks. The collection, storage, and use of biologic samples in future research from acutely ill patients raise unique logistical and ethical challenges,184 particularly regarding confidentiality, accuracy of substituted judgments, ownership, and the commercialization of stored biologic samples. There has also been a lack of consensus regarding the type and quality of informed consent needed to collect and store samples for future, unspecified research.185 Finally, as research has become increasingly globalized, ethical issues also arise from collaborative international research in which samples are collected in developing countries and then exported for analysis to developed countries.186

Response to Disaster

Critical care practitioners may be called upon to participate in responding to natural and human-made disasters. As such they should be familiar with crisis standards of care developed by the Institute of Medicine (IOM)187 and recommendations from the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine regarding benchmarks for management of critical illness when disasters occur. They are obliged to be well prepared with regard to key functions and assets including triage, infrastructure, essential equipment, sufficient personnel, protection of staff and patients, medical procedures, hospital policy, coordination and collaboration with interface units, registration and reporting, administrative policies, and education.188 The IOM committee has argued that when crisis standards of care prevail, as when ordinary standards are in effect, health care practitioners must adhere to ethical norms. Conditions of overwhelming scarcity limit autonomous choices for both patients and practitioners regarding the allocation of scarce health care resources but do not permit actions that violate ethical norms. It has recognized that ethical considerations are one of the key elements of crisis standards of care protocols and that the most relevant ethical considerations are fairness, duty to care, duty to steward resources, transparency, consistency, proportionality, and accountability.189

References

1. DuVal, G, Clarridge, B, Gensler, G, Danis, M. A national survey of U. S. internists’ experiences with ethical dilemmas and ethics consultation. J Gen Intern Med. 2004; 19:251–258.

2. Beauchamp, TL, Childress, JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

3. Emanuel, EJ, Emanuel, LL. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992; 267:2221–2226.

4. Cohen, CB. Can autonomy and equity coexist in the ICU? Hastings Cent Rep. 1986; 16(5):39–41.

5. Cook, D. Patient autonomy versus paternalism. Crit Care Med. 2001; 29:N24–N25.

6. Murray, E, Pollack, L, White, M, Lo, B. Clinical decision-making: Patients’ preferences and experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2007; 65(2):189–196.

7. Azoulay, E, Pochard, F, Chevret, S, et al. Half the family members of intensive care unit patients do not want to share in the decision-making process: A study in 78 French intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:1832–1838.

8. Davidson, J. Do cultural differences in communication and visiting result in decreased family desire to participate in decision making? Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:1964–1966.

9. Levy, MM. Shared decision-making in the ICU: Entering a new era. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:1966–1968.

10. Nelson, JL, Nelson, HL. Guided by intimates. Hastings Cent Rep. 1993; 23:14–15.

11. Kuczewski, MG. Reconceiving the family. The process of consent in medical decision making. Hastings Cent Rep. 1996; 26:30–37.

12. Davidson, JE, Powers, K, Hedayat, KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med. 2007; 5:2–18.

13. Browning, G, Warren, NA. Unmet needs of family members in the medical intensive care waiting room. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2006; 29:86–95.

14. Koenig, B, Gates-Williams, J. Understanding cultural differences in caring for dying patients. West J Med. 1995; 163:244–249.

15. Danis, M. Role of ethnicity, race, religion, and socioeconomic status in end of life care in the ICU. In: Curtis JR, Rubenfeld GD, eds. The Transition from Cure to Comfort: Managing Death in the Intensive Care Unit. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

16. Mir, NU. Breaking bad news: Practical advice for busy doctors. Hosp Med. 2004; 65:613–615.

17. Lingren, VA, Ames, NJ. Caring for patients on mechanical ventilation: What research indicates is best practice. Am J Nurs. 2005; 105:50–60.

18. Appelbaum, PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:1834–1840.

19. Cohen, LM, McCue, JD, Green, GM. Do clinical and formal assessments of the capacity of patients in the intensive care unit to make decisions agree? Arch Intern Med. 1993; 153:2481–2485.

20. Jain, M, Miller, L, Belt, D, et al. Decline in ICU adverse events, nosocomial infections and cost through a quality improvement initiative focusing on teamwork and culture change. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006; 15:235–239.

21. Mills, AE, Spencer, EM. Values based decision making: A tool for achieving the goals of healthcare. HEC Forum. 2005; 17:18–32.

22. Baker, R, Strosberg, M. Triage and equality: An historical reassessment of utilitarian analyses of triage. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1992; 2:103–123.

23. Swenson, MD. Scarcity in the intensive care unit: Principles of justice for rationing ICU beds. Am J Med. 1992; 92:551–555.

24. Engelhardt, HT, Rie, MA. Intensive care units, scarce resources, and conflicting principles of justice. JAMA. 1986; 255:1159–1164.

25. Task Force on Guidelines, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Recommendations for intensive care unit admission and discharge criteria. Crit Care Med. 1988; 16:807–808.

26. Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Guidelines for intensive care unit admission, discharge, and triage. Crit Care Med. 1999; 27:633–638.

27. Dawson, JA. Admission, discharge, and triage in critical care. Crit Care Clin. 1993; 9:555–574.

28. Teres, D. Civilian triage in the intensive care unit: The ritual of the last bed. Crit Care Med. 1993; 21:598–606.

29. Terry, P, Rushton, CH. Allocation of scarce resources: Ethical challenges, clinical realities. Am J Crit Care. 1996; 5:326–330.

30. Cooper, AB, Joglekar, AS, Gibson, J, et al. Communication of bed allocation decisions in a critical care unit and accountability for reasonableness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005; 5:67.

31. Truog, RD, Brock, DW, Cook, DJ, et al. Rationing in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:958–963.

32. Knaus, W. Ethical implications of risk stratification in the acute care setting. Cambridge Q Healthcare Ethics. 1993; 2:193–196.

33. Latour, J, Lopez, V, Rodriguez, M, et al. Inequalities in health in intensive care patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991; 44:889–894.

34. Danis, M, Linde-Zwirble, WT, Astor, A, et al. How does lack of insurance affect use of intensive care? A population-based study. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:2043–2048.

35. Schneiderman, LJ, Gilmer, T, Teetzel, HD, et al. Effects of ethics consultation on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003; 290:1166–1172.

36. DeGrazia, D, The definition of deathZalta EN, ed. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2011. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2011/entries/death-definition/

37. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death. A definition of irreversible coma. JAMA. 1968; 205(6):337–340.

38. President’s Commission on Ethical Problems and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Defining Death. A Report on the Medical, Legal, and Ethical Issues in Definition of Death. Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office; 1981.

39. Snead, OC, President’s Council on Bioethics. Controversies in the determination of death. President’s Council on Bioethics, Washington, DC, 2008. http://bioethics.georgetown.edu/pcbe/reports/death/chapter1.html

40. Shewmon, DA. The brain and somatic integration: Insights into the standard biological rationale for equating “brain death” with death. J Med Philos. 2001; 26:457–478.

41. Shewmon, DA. Chronic “brain death”: Meta-analysis and conceptual consequences. Neurology. 1998; 51:1538–1545.

42. Jonsen, AR, Siegler, M, Winsalde, WJ. Clinical Ethics, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

43. Huang, J, Millis, JM, et al. A pilot program of organ donation after cardiac death in China. Lancet. 2012; 379:862–865.

44. Aita, K. New organ transplant policies in Japan, including the family-oriented priority donation clause. Transplantation. 2011; 91:489–491.

45. Hippocrates. The art. In: Jones WHS, ed. Hippocrates. The Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1923.

46. Bigelow, J. Self-limited disease: Address to the Massachusetts Medical Society, May 27, 1835. In: Bigelow J, ed. Nature in Disease. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1854.

47. Warren, J. Etherization, with Surgical Remarks. Boston: Ticknor & Co. ; 1848.

48. Pope Pius XII. The prolongation of life. In: Reiser SJ, Dyck AJ, Curran WJ, eds. Ethics in Medicine. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1977.

49. In re Quinlan, 70 N. J. 10 (1976).

50. Beauchamp, TL, Childress, JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009.