Objectives

• Discuss ethical principles as they relate to critical care patients.

• Discuss strategies to address moral distress in critical care nursing.

• Discuss the concept of medical futility.

• Describe what constitutes an ethical dilemma.

• List steps for making ethical decisions.

• Identify legal and professional obligations of critical care nurses.

• Describe the elements of certain torts that may result from critical care nursing practice.

• Identify and discuss specific legal issues in critical care nursing practice.

![]()

Be sure to check out the bonus material, including free self-assessment exercises, on the Evolve web site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Urden/priorities/.

Morals and Ethics

Morals are the “shoulds,” “should nots,” “oughts,” and “ought nots” of actions and behaviors and have been related closely to sexual mores and behaviors in Western society. Religious and cultural values and beliefs largely mold a person’s moral thoughts and actions. Morals form the basis for action and provide a framework for evaluation of behavior.

Ethics is concerned with the “why” of the action rather than with whether the action is right or wrong, good or bad. Ethics implies that an evaluation is being made and is theoretically based on or derived from a set of standards.

Moral Distress

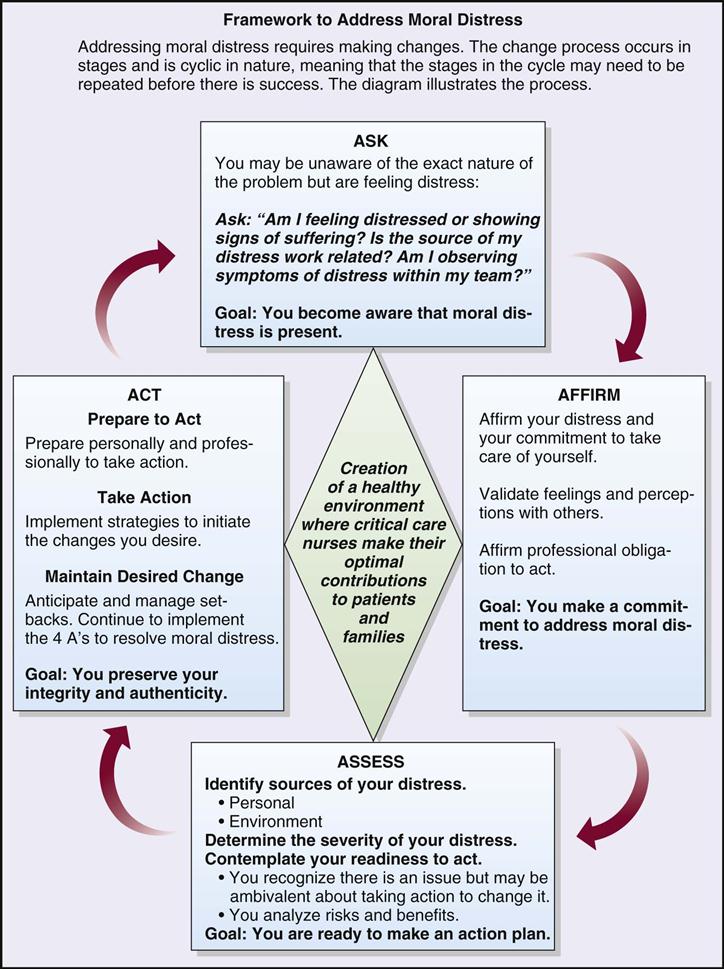

Moral distress is a serious problem for nurses. It occurs when one knows the ethically appropriate action to take but cannot act upon it. It also presents when one acts in a manner contrary to personal and professional values. There can be an internal conflict when one’s ethical framework clashes with the ethical beliefs of the patient.1,2 As a result, there can be significant emotional and physical stress that leads to feelings of loss of personal integrity and dissatisfaction with the work environment.3 Relationships with both co-workers and patients are affected and can negatively impact the quality of care. There is also a great impact on personal relationships and family life. It is therefore important that nurses recognize moral distress and actively seek strategies to address the issue through institutional, personal, and professional organizational resources. Knowledge and application of ethical principles and guidelines will assist the nurse in daily practice when ethical dilemmas occur. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) has written a position statement on moral distress that describes the phenomenon and lists actions for individual nurses and employers to address moral distress. Refer to Box 2-1. The AACN3,4 has created a framework to support those nurses who are experiencing moral distress (Figure 2-1).

Ethical Principles

Certain ethical principles were derived from classic ethical theories that are used in health care decision making. Principles are general guidelines that govern conduct, provide a basis for reasoning, and direct actions. The six ethical principles discussed here are autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, veracity, fidelity, and justice (Box 2-2).

Autonomy

The concept of autonomy appears in all ancient writings and early Greek philosophy. In health care, autonomy can be viewed as the freedom to make decisions about one’s own body without the coercion or interference of others. Autonomy is a freedom of choice or a self-determination that is a basic human right. It can be experienced in all human life events. Involving the patient and family in decision making is also an indication of respect and family-centered care.5

The critical care nurse is often “caught in the middle” in ethical situations, and promoting autonomous decision making is one of those situations. As the nurse works closely with patients and families to promote autonomous decision making, another crucial element becomes clear. Patients and families must have all the information about a particular situation before they can make a decision that is best for them. They not only should be given all the pertinent information and facts but also must have a clear understanding of what was presented.6 In this situation the nurse assumes one of the most important roles of the health care team, that is, as patient advocate, providing more information as needed, clarifying points, reinforcing information, and providing support during the decision-making process.

Beneficence

The concept of doing good and preventing harm to patients is a sine qua non for the nursing profession. However, the ethical principle of beneficence, which requires that one promote the well-being of patients, indicates the importance of this duty for the health care professional. The principle of beneficence presupposes that harms and benefits are balanced, leading to positive or beneficial outcomes.

In approaching issues related to beneficence, conflict with the principle of autonomy is common. Paternalism exists when the nurse or physician makes a decision for the patient without consulting the patient.

Traditional health care has been based on a paternalistic approach to patients. Many patients are still more comfortable in deferring all decisions about care and treatment to their health care provider. Active involvement by various organizations and agencies in regard to health care has demonstrated a trend toward the public’s need and desire for more information about health care in general, as well as more about alternative treatments and providers. Paternalism, or maternalism in the case of female providers, may always be a possibility in the health care setting, but enlightened consumers are causing a change in this practice of health care professionals.

Nonmaleficence

The ethical principle of nonmaleficence, which dictates that one prevent harm and correct harmful situations, is a prima facie duty for the nurse. Thoughtfulness and care are necessary, as is balancing risks and benefits. Beneficence and nonmaleficence are on two ends of a continuum and are often adhered to differently, depending on the views of the practitioner.

Veracity

Veracity, or truth telling, is an important ethical principle that underlies the nurse-patient relationship. Communication trust, or the trust of disclosure, is rooted in respect and based on veracity.7

Veracity is important when soliciting informed consent because the patient needs to be aware of all potential risks of and benefits to be derived from specific treatments or alternative therapies.8–10 Again, the critical care nurse may be in the middle of a situation where all the facts and information about a particular treatment option are not disclosed. Sometimes information has been given accurately to the patient and family but has been delivered with bias or in a misleading way. Veracity must guide all areas of practice for the nurse, that is, in colleague relationships and employee relationships, as well as in the nurse-patient relationship.

Fidelity

Fidelity, or faithfulness and promise keeping to patients, is also a sine qua non for nursing. It forms a bond between individuals and is the basis of all relationships, both professional and personal. Regardless of the amount of autonomy that patients have in the critical care areas, they still depend on the nurse for many types of physical care and emotional support. A trusting relationship that establishes and maintains an open atmosphere is positive for all involved.11 Making a promise to a patient is voluntary for the nurse, whereas having respect for a patient’s decision making is a moral obligation.12

Fidelity extends to the family of the critical care patient. When a promise is made to the family that they will be called if an emergency arises or that they will be informed of any other special events concerning the patient, the nurse must make every effort to follow through on the promise. Fidelity not only will uphold the nurse-family relationship but also will reflect positively on the nursing profession as a whole and on the institution where the nurse is employed.

Confidentiality is one element of fidelity that is based on traditional health care professional ethics. Confidentiality is described as a right whereby patient information can be shared only with those involved in the care of the patient. An exception to this guideline might be when the welfare of others will be put at risk by keeping patient information confidential. Again in this situation, the nurse must balance ethical principles and weigh risks with benefits. Special circumstances, such as the existence of mandatory reporting laws, will guide the nurse in certain situations.

Privacy also has been described as being inherent in the principle of fidelity. Privacy may be closely aligned with confidentiality of patient information and a patient’s right to privacy of his or her person, such as maintaining privacy for the patient by pulling the curtains around the bed or making sure that the patient is adequately covered.

Justice

The principle of justice is often used synonymously with the concept of allocation of scarce resources. With escalating health care costs, expanded technologies, an aging population with their own special health care needs, and in some cases a scarcity of health care personnel, the question of how to allocate health care becomes even more complex. With the recent passage of landmark legislation that will lead to major changes in health care, numerous questions are presently unanswered about the impact on our citizens.13

The application of the justice principle in health care is concerned primarily with divided or portioned allocation of goods and services, which is termed distributive justice. As health care resources become increasingly scarce, allocation of resources to certain programs and rationing of resources within certain programs will become more evident.

Medical Futility

The concept of medical futility has resulted in various discussions and proposed criteria and formulas to predict outcomes of care.14–16 Medical futility has both a qualitative and a quantitative basis and can be defined as “any effort to achieve a result that is possible but that reasoning or experience suggests is highly improbable and that cannot be systematically reproduced.”17

Therapy or treatment that achieves its predictable outcome and desired effect is, by definition, effective. Effect must be distinguished from benefit, however; although predictable and desired, the effect is nonetheless futile if it is of no benefit to the patient.

Ethical Foundation for Nursing Practice

Traditional theories of professions include a code of ethics upon which the practice of the profession is based. It is by adherence to a code of ethics that the professional fulfills an obligation to provide quality practice to society.

A professional ethic forms the framework for any profession18 and is based on three elements: (1) the professional code of ethics, (2) the purpose of the profession, and (3) the standards of practice of the professional. The code of ethics developed by the profession is the delineation of its values and relationships with and among members of the profession and society. The need for the profession and its inherent promise to provide certain duties form a contract between nursing and society. The professional standards describe specifics of practice in a variety of settings and subspecialties. Nursing professionals must stay consistent with their values and ethics, and ensure that the ethical environment is maintained wherever nursing care and services are performed.19,20 Each element is dynamic, and ongoing evaluations are necessary as societal expectations change, technologies increase, and the profession evolves.

Nursing Code of Ethics

The American Nurses Association (ANA) provides the major source of ethical guidance for the nursing profession. The Code of Ethics for Nurses serves as the basis for nurses in analyzing ethical issues and decision making (Box 2-3).21

What Is An Ethical Dilemma?

In general, ethical cases are not always clear-cut or “black and white.” The most common ethical dilemmas encountered in critical care are forgoing treatment and allocating the scarce resources of critical care. Before the application of any decision model is made, it must be determined whether a true ethical dilemma exists. Thompson and Thompson22 delineate the following three criteria for defining moral and ethical dilemmas in clinical practice:

One must pause, expand group consciousness about the issue, validate assumptions, look for patterns of thoughts or behaviors, and facilitate reflection and inquiry prior to making any decision.23

Steps in Ethical Decision Making

To facilitate the ethical decision-making process, a model or framework must be used so that all parties involved will consistently and clearly examine the multiple ethical issues that arise in critical care. There are various ethical decision-making models in the literature.24,25 Box 2-4 lists steps in a model that will be briefly discussed in this chapter.

Step One

First, the major aspects of the medical and health problems must be identified. In other words, the scientific basis of the problem, potential sequelae, prognosis, and all data relevant to the health status must be examined.

Step Two

The ethical problem must be clearly delineated from other types of problems. Systems problems result from failures and inadequacies in the health care facility’s organization and operation or in the health care system as a whole and are often misinterpreted as ethical issues. Social problems arising from conditions in the community, state, or country as a whole also are occasionally confused with ethical issues. Social problems can lead to systemic problems, which can constrain responses to ethical problems.

Step Three

Although categories of necessary additional information will vary, whatever is missing in the initial problem presentation should be obtained. If not already known, the health prognosis and potential sequelae should be clarified. Usual demographic data (e.g., age, ethnicity, religious preferences, educational/economic status) may be considered in the decision-making process. The role of the family or extended family and other support systems needs to be examined. Any desires that the patient may have expressed about the treatment decision, either in writing or in conversation, must be obtained.

Step Four

The patient is the primary decision maker and autonomously makes these decisions after receiving information about the alternatives and sequelae of treatments or lack of treatment. In many ethical dilemmas the patient is not competent to make a decision, however, as when the patient is comatose or otherwise physically or mentally unable to make a decision. In these cases, surrogates are designated or court appointed because the urgency of the situation requires a quick decision.

Others who are involved in the decision also need to be identified at this time, such as family, nurse, physician, social worker, clergy, and members of other disciplines in close contact with the patient. The role of the nurse must be examined. It may not be necessary for the nurse to make a decision at all; rather, the nurse’s role may be simply to provide additional information and support to the decision maker.

Step Five

Personal values, beliefs, and moral convictions of all persons involved in the decision-making process need to be known. Whether actually achieved through a group meeting or through personal introspection, values clarification facilitates the decision-making process.

General ethical principles also need to be examined in regard to the case at hand. For example, are veracity, informed consent, and autonomy being promoted? Beneficence and nonmaleficence will be analyzed as they relate to a patient’s condition and desires. Close examination of these principles will reveal any compromise of ethical or moral principles for either the patient or the health care provider and will assist in decision making.

Step Six

After the identification of alternative options, the outcome of each action must be predicted. This analysis helps the person select the option with the best “fit” for the specific situation or problem. Both short- and long-range consequences of each action must be examined, and new or creative actions must be encouraged. Consideration also must be given to the “no action” option, which is another choice.

Step Seven

When a decision has been reached, it is usually after much thought and consideration.

Step Eight

Evaluation of an ethical decision serves both to assess the decision at hand and to provide a basis for future ethical decisions. If outcomes are not as predicted, it may be possible to modify the plan or to use an alternative that was not originally chosen.

Legal Relationships

When a professional nurse commences employment in a critical care facility, three legal relationships are formed. First, on accepting employment, the relationship between the nurse and the employer is formed. Second, on assuming the care of a patient, a relationship is created between the patient and nurse. Third, every state has a law that mandates the entry-level educational requirements that must be met for a person to become licensed to practice nursing. The act of licensing creates a legal relationship between the nurse and the state.

These relationships impose legal obligations. The nurse owes a patient the duty of reasonable and prudent care under the circumstances. The nurse owes the employer the duty of competency and the ability to follow policies and procedures; other contractual duties may exist as well. The nurse owes the state and public the duty of safe, competent practice as legally defined by practice standards.

The critical care nurse’s legal duties are enforceable, and the nurse can be held legally accountable for breach or violation through a variety of laws and legal processes. Nurses, hospitals, patients, and other health care providers can be involved in a variety of legal disputes, including negligence and professional malpractice, incompetence, unauthorized practice, unprofessional or illegal conduct, workers’ compensation, and contract and labor disputes.

Tort Liability

The area of civil law is divided into many categories, two of which are contracts and torts. The law of contracts contains a set of rules governing the creation and enforcement of an agreement between two or more parties (entities or individuals). For example, contract law may apply to a dispute between the nurse, as employee, and an institution, as employer. In contrast, a tort is a type of civil wrong or injury that results from a breach of a legal duty. Tort law is generally divided into intentional and unintentional torts, strict liability, and specific torts (Box 2-5).

Intentional torts involve (1) a mind-set indicative of purpose and (2) an act. Intent exists when the person forms a mental design to achieve a particular outcome and consequence. Assault, battery, false imprisonment, trespass, and intentional infliction of emotional distress are all examples of intentional torts. In each of these torts, a specific act is required, and there is purposeful interference with a person or property.

In assault the act is a behavior that places the plaintiff (person being wronged who later sues) in fear or apprehension of offensive physical contact; in civil law the defendant is the person being sued for wronging another. Battery is the unlawful or offensive touching of or contact with the plaintiff or something attached to the plaintiff. False imprisonment is detaining, confining, or restraining another against the person’s will. The two types of trespass involve (1) a person’s land and (2) an individual’s personal property. These acts are defined as “unauthorized entry onto land of another” or “unauthorized handling of another’s personal property.” In addition, the law protects a person’s interest in peace of mind through the tort claim of infliction of mental or emotional distress. The act in this case, however, must involve extreme misconduct or outrageous behavior.

Unintentional torts involve failures or breach of nursing duties that lead to harm, including negligence, malpractice, and abandonment. Negligence is the failure to meet an ordinary standard of care, resulting in injury to the patient or plaintiff. Malpractice is a type of professional liability based on negligence and includes professional misconduct, breach of a duty or standard of care, illegal or immoral conduct, or failure to exercise reasonable skill, all of which lead to harm (see later discussion). Abandonment is a type of negligence in which a duty to give care exists, is ignored, and results in harm to a patient. It is the absence of care and the failure to respond to a patient that may give rise to an allegation of abandonment.

Specific torts involve privacy and reputation interests and include invasion of privacy and defamation. Defamation is composed of two torts: slander (oral defamation) and libel (written defamation). Defamation is not the mere statement or writing of words that injures a person’s reputation or good name; the words also must be communicated to another. If the words are true, this may provide a defense against a defamation claim. Invasion of privacy involves the violation of a person’s right to privacy. Nurses can invade another’s privacy by revealing confidential information without authorization or by failing to follow the patient’s health care decisions.

Nurses can avoid allegations of these specific claims by (1) making statements about another’s reputation only when necessary and substantiated by fact and (2) respecting another’s privacy and autonomy and maintaining a confidential relationship with the patient.

Administrative Law and Licensing Statutes

A second type of law and legal process in which nurses are involved is administrative law and the regulatory process. This area of law governs the nurse’s relationship with the government, either state or federal. Administrative law involves the rules of the government’s activities in regulating health care delivery and practice; the rules of investigation, procedure, and evidence differ from those of civil and criminal law. Several government health care agencies are involved in such regulation.

A state has the power to regulate nursing because the state is responsible for the health, safety, and welfare of its citizens. Therefore, establishing minimal entry-level requirements, standards of nursing practice, and educational requirements are acceptable state actions. State legislatures create laws governing nursing practice, generally termed nurse practice acts, and a unit of the state government within the executive branch is responsible for the enforcement of nursing laws. This unit is often called the State Board of Nursing or Board of Nurse Examiners; however, the name varies by state. Standards also vary by state, which is another important reason that nurses should seek advice from counsel licensed to practice law in their own state. Because law is the minimum expected behavior, the profession oftentimes sets a higher standard. Additional methods to ensure competency are continuing education for renewal of license, work-based orientation programs, and certification in specialty practice areas. Self-reflection and assessment of one’s current competencies and level of technical knowledge can serve to elevate practice.26

Negligence and Malpractice

As defined earlier, negligence is an unintentional tort involving a breach of duty or failure (through an act or an omission) to meet a standard of care, causing personal harm. Malpractice is a type of professional liability based on negligence in which the defendant is held accountable for breach of a duty of care involving special knowledge and skill. These torts have several elements, all of which the plaintiff has the burden of proving.

The law recognizes four elements of negligence and malpractice. The first element, a duty, or legal obligation, requires the person (“actor”) to conform to a certain standard of conduct for the protection of others against unreasonable risks. The critical care nurse’s legal duty is to act in a reasonable and prudent manner, as any other critical care nurse would act under similar circumstances. The standard is that of a critical care nurse, a professional with special knowledge and skill in critical care. The standard is that owed at the time the incident or injury occurred, not at the time of litigation. In most jurisdictions the standard of care is a national standard, as opposed to a local or community standard. General critical care nursing duties are implied by statute and administrative rules and regulations and are stated explicitly in judicial decisions (Box 2-6).

The second element, breach of duty, involves a failure on the actor’s part to conform to the standard required. Causation, the third element, involves proving that the actor’s breach was reasonably close or causally connected to the resulting injury. This is also referred to as proximate cause. The fourth element, injury or damages, must involve an actual loss or damage to the plaintiff or his or her interest. A plaintiff may claim different types of damages, such as compensatory and punitive. Patient injury can range in value, depending on what happened to the patient. The plaintiff must produce evidence of the damages and their value. If the nurse breaches a standard of care that leads to injury, the plaintiff must show what amount of money will compensate for his or her injuries. The goal of the compensation is to provide the amount of money that will return the plaintiff to the position that existed before the injury occurred.

Res ipsa loquitur, “the thing speaks for itself,” is a rule of evidence used by plaintiffs in negligence or malpractice litigation. It is a rebuttable presumption or inference of negligence by the defendant, which arises on the plaintiff’s proof that (1) the injury is one that ordinarily does not happen in the absence of negligence and (2) the instrumentality causing the injury was in the defendant’s exclusive management and control. The burden then shifts to the defendant to prove absence of negligence. For example, negligence can be inferred when muscle ischemia and necrosis occur as a result of improper body positioning and the application of splints or restraints. Negligence can also be inferred from a foreign object left in a patient’s body cavity after surgery.

Because critical care nurses deal with life-threatening situations, any patient injury is potentially severe or may result in death. Should the injury occur as a result of alleged negligence, the nurse may be held liable for the patient’s death and also for the resulting loss to surviving family members. All states have “wrongful death” acts, and a number of states have both “death” acts and “survival” acts, which are prosecuted concurrently. With the two causes of action, the expenses, pain and suffering, and loss of earnings of the decedent up to the time of death are allocated to the survival action, and loss of benefits to the survivors is allocated to the wrongful death action.

Specific critical care nursing actions have resulted in litigation (Box 2-7). In such cases the nurse’s action is central to the lawsuit. However, nurses are named as sole defendant or codefendant in a comparatively small percentage of cases. Although this pattern is changing, physicians and hospitals are generally named as defendants.

Typically, nursing negligence cases involve breach or failure in six general categories (Box 2-8). The first category includes the use of defective equipment or the failure to perform safety and maintenance assessments. Nurses have made errors in drug identification, administration, and dosages. Nurses have failed to report changes in patient status to physicians in a timely manner. Nurses have not communicated to supervisors a physician’s failure to respond to the nurse’s communication. Failure to supervise and assist patients who subsequently fall is also a source of nursing negligence. Improper wound care with resulting infection and incorrect instrument and sponge counts in the surgical setting have also led to patient injury and lawsuits.

It is important to report and document any adverse event or unexpected outcome in an honest and genuine manner. Disclosure should take place as soon as possible after the event has been identified. This information needs to be orally discussed with the patient and family and documented. Documentation, also upon identification of the issue, needs to include the date, time, place, and all individuals involved, including the discussion with the patient and family. Document the discussion with the patient and family (use quotations of any key statements of anyone involved), the follow-up plan, and any subsequent discussions. The documentation must be accurate and concise with no admission of guilt or negligence.27

Legal Doctrines and Theories of Liability

In tort law the nurse’s action may be examined and legal duties defined according to the following theories of liability:

• Vicarious liability: respondeat superior

• Other liability doctrines (e.g., temporary or borrowed servant, captain of the ship)

Under the theory of personal liability, each individual is responsible for his or her own actions, including the critical care nurse, supervisor, physician, hospital, and patient. Each has responsibilities that are uniquely his or her own. In contrast to personal liability, the individual may be afforded the protection of personal immunity.

Vicarious liability is indirect responsibility, such as the liability of an employer for the acts of the employee. Under the doctrine of respondeat superior, a “master” is liable for certain wrongful acts of a “servant,” as is a principal for those of an agent. An employer may be liable for an employee’s acts that are performed within the legitimate scope of employment. In critical care the nurse typically is an employee of a hospital. However, nurses may be independent contractors with the hospital through critical care nursing agencies or businesses. If the latter is the case, the nurse is not an employee of the hospital, and the hospital is not vicariously liable for the nurse’s action.

Corporate liability is the liability attached to the corporate entity (e.g., the hospital) for its own corporate activities and decisions.

Other doctrines, such as temporary servant or borrowed servant and captain of the ship, may apply to the critical care nurse and the critical care unit. These doctrines are used when the plaintiff argues that the physician is responsible for the nurse’s actions, even though the nurse is an employee of the hospital, not of the physician. If it can be shown that the nurse acted under the direction and control of the physician, the physician may be accountable for the nurse’s actions. However, these doctrines are becoming increasingly uncommon. What viability remains is typically found in cases involving nurse anesthetists and operating room nurses.

Nurse Practice Acts

The practice of nursing is regulated by the state. As a general rule, the state’s police power to regulate prevails, as long as the state’s actions are not arbitrary or capricious. All nurses must be licensed to practice under their individual state’s licensure statutes. Licensure authorizes (1) the right to practice and (2) access to employment. Therefore licensure is a property right that is constitutionally protected. Every state has legislation that defines the legal scope of nursing practice and defines unprofessional and illegal conduct that may lead to investigation and disciplinary action by the state and sanctions on the right to practice. The state nurse practice act establishes entry requirements, definitions of practice, and criteria for discipline. Although licensure is mandatory for registered nurses (RNs), statutory content varies among the states.

Generally, state law contains two definitions of nursing: one for the RN (or professional nurse) and one for the licensed practical (or vocational or technical) nurse. These definitions determine titles that may be used by nurses, the scope of nursing practice, and requirements for entering the nursing profession. In some states, advanced RN practice, prescriptive authority for certain nurses, and third-party reimbursement are also defined by statute.

Mandatory continuing education requirements are also defined by statute in most states. The state authorizes its board of nursing to monitor practice, implement standards of care, enforce rules and regulations, and issue sanctions. Sanctions include additional education, restricted practice, supervised practice, license suspension, and license revocation. Some form of disciplinary action generally occurs as a result of unauthorized practice, negligence or malpractice, incompetence, chemical or other impairment, criminal acts, or violations of specific nurse practice act provisions.

The scope of medical practice is also statutorily defined, and in most states a physician is given broad discretion to delegate tasks to others. Physicians may delegate to critical care nurses through written protocols or standing orders, which must be written, dated, and signed by the physician; standing orders and protocols must be updated regularly. The nurse must be adequately prepared to follow the protocol and perform with a reasonable degree of skill, care, and diligence as performed by similar nurses under similar circumstances. Protocol and standing orders should identify unambiguously the corresponding roles of hospital administrators, nurses, and physicians. Within a state’s jurisdiction, however, the scope of medical practice and the scope of nursing practice often overlap because each practice may authorize the same functions. Such overlapping creates problems at the regulatory level and will expand as the role of nursing continues to evolve.

Chemical impairment is a common reason for disciplinary action. In some states the impaired nurse may avoid serious sanctions by voluntarily suspending practice and entering a rehabilitation program. This must be done with the advice of counsel (the nurse’s own lawyer). Generally, this option is available as long as no patient has been harmed because of the nurse’s impairment.

Specific Patient Care Issues

Myriad legal issues and controversies exist in the field of critical care. Concerns often arise in the areas of (1) informed consent and authorization for treatment and (2) the patient’s right to accept or refuse medical treatment.

Informed Consent and Authorization for Treatment

There are two types of consent: express and implied. Express consent may be written or verbal and is the consent given specifically for nonroutine procedures. Implied consent may be implied in fact, an assumption based on patient behavior (e.g., patient extending arm for venipuncture or nodding approval), or may be implied in law (e.g., unconscious, hemorrhaging patient in emergency department). This discussion summarizes the elements of valid informed consent, the adequacy of consent and negligent nondisclosure, and exceptions to consent requirements and the duty to disclose.

Valid consent must be (1) voluntary, (2) obtained, and (3) informed. Although consent can be verbal or written, most hospital policies require that informed, voluntary consent to nonroutine procedures be obtained and confirmed in writing, as signed and dated by the patient, physician, and witness (if required). Most informed consent statutes provide that a consent in writing to a medical or surgical procedure that meets the consent and disclosure requirements of the statute creates a legal presumption that informed consent was given. Research has shown that participant comprehension of the informed consent process continues to be deficient in how much the persons who sign consents actually know and/or understand.28

In the vast majority of jurisdictions the decision maker (person giving consent) must be a legally competent adult (i.e., having reached age of majority, or age 18 years in most states). Competence is a legal judgment, and as a general rule, there is a legal presumption of patient competence.29 A person is mentally incompetent (thereby rendering a consent invalid) if adjudicated incompetent. A person must likewise have the capacity (a medical and nursing judgment) to give consent. The patient must be oriented and understand what he or she has been told, and current medications must be documented. For adults legally adjudicated incompetent, the guardian may give consent if the guardian has been given this authority.

Minors are legally incompetent, and consent is obtained from the parent or guardian. In many jurisdictions, however, there are two important exceptions to this rule: (1) mature minors may consent to treatment for substance abuse, sexually transmitted disease, and matters involving contraception and reproduction; and (2) emancipated minors may consent to treatment in general. Minors are considered “emancipated” if married or divorced before the age of majority, if in the military service, or if living independently with parental consent.

Consent must also be informed and timely. The physician has a duty to disclose the diagnosis, condition, prognosis, material risks/benefits associated with the treatment or procedure, explanation of the treatment, providers of the treatment (who is performing, supervising, and assisting in procedure), material risks and benefits of alternative therapy, and the probable outcome (including material risks/benefits) if the patient refuses the treatment or procedure. Failure to disclose such information or inadequate disclosure with resultant injury may constitute negligence and give rise to tort claims of malpractice, battery, negligent nondisclosure, and abandonment. Consent is generally valid for 7 to 30 days. However, the time at which consent expires must be explicitly stated in the institutional policy and procedure manual.

There are many exceptions to consent requirements and the duty to disclose, and clearly the exceptions vary according to jurisdiction. Emergencies constitute one exception, unless the patient refuses treatment or has previously made a competent and informed refusal. States vary significantly in the following treatment situations: endangered fetal viability, alcohol or other drug detoxification, emergency blood transfusion, cesarean birth, and substance abuse during pregnancy. Jurisdictions also vary on the issue of sources of consent (informal directives) for the incompetent patient or the patient in an emergency who has no legal guardian. Alternatives include consensus from as many next of kin as possible, with evidence that (1) the treatment is reasonable and necessary and (2) the family’s decision would not be contrary to the patient’s wishes, known as substituted judgment (made by a surrogate decision maker). Another alternative is a court order for treatment. In the absence of substituted judgment, many courts use the “best interests” standard.

Right to Accept or Refuse Medical Treatment

The right to consent and informed consent includes the right to refuse treatment. In most cases a competent adult’s decision to refuse even life-sustaining treatment is honored.30–34 The underlying rationale is that the patient’s right to withdraw or withhold treatment is not outweighed by the state’s interest in preserving life. The right to refuse treatment is not honored in some situations, including (but not limited to) the following:

1 The treatment relates to a contagious illness that threatens the health of the public.

3 The refusal violates ethical standards.

4 Treatment must be instituted to prevent suicide and to preserve life.

When patients refuse treatment, complex ethical, legal, and practical problems arise. Hospitals should have specific policies to guide nurses in these areas, and nurses’ participation in hospital or institutional ethics committees is strongly advised.

Withholding and Withdrawing Treatment

As stated, an adult has the right to refuse treatment, even treatment that sustains life. This right means that the critical care nurse may participate in the withholding or withdrawing of treatment. Historically, the distinction between withholding and withdrawing treatment was considered the issue of importance, but this is no longer the case. Health care decisions become most complex when patients lose competency and capacity to make their own decisions personally.

Advance Directives

The U.S. Congress passed landmark legislation known as the Patient Self-Determination Act/Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1990.35–44 The statute requires that all adults must be provided written information on an individual’s rights under state law to make medical decisions, including the right to refuse treatment and the right to formulate advance directives.

The law mandates that providers of health care services under Medicare and Medicaid must comply with requirements relating to patient advance directives, which are written instructions recognized under state law for provisions of care when persons are incapacitated. Providers may not be reimbursed for the care they provide unless the requirements of this provision are met. Despite various methods to inform patients about the importance of having advance directives, there are still persons seeking health care who do not have completed advanced health care directives in place.45

Providers must have written policies and procedures (1) to inform all adult patients at initiation of treatment of their right to execute an advance directive and of the provider’s policies on the implementation of that right, (2) to document in the medical record whether an individual has executed an advance directive, (3) not to condition care and treatment or otherwise discriminate on the basis of whether a patient has executed an advance directive, (4) to comply with state laws on advance directives, and (5) to provide information and education to staff and the community on advance directives.

Patients themselves can provide clear direction by preparing in advance written documents that specify their wishes.46 These documents are termed advance directives and include the living will and durable power of attorney for health care. To be effective in a jurisdiction, both these directives must be statutorily or judicially recognized. The living will specifies that if certain circumstances occur, such as terminal illness, the patient will decline specific treatment, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and mechanical ventilation. The living will does not cover all treatment; in some states, for example, nutritional support may not be declined through a living will. The durable power of attorney for health care is a directive through which a patient designates an “agent,” someone who will make decisions for the patient if the patient becomes unable to do so. Critical care nurses whose patients have executed advance directives must follow state law provisions and the hospital’s policies and require education regarding advance directives and their important role in patient advocacy.47

Orders Not To Resuscitate

Hospital policies that address orders to withhold or withdraw treatment should exist in all critical care units. For example, orders not to resuscitate, typically referred to as do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, should be governed by written policies, including (but not limited to) the following:

2 DNR orders should have the concurrence of another physician designated in the policy.

3 Policies should specify that orders are reviewed periodically (some policies require daily review).

4 Patients with capacity must give their informed consent.

7 Policies should specify who is to be contacted and notified within the hospital administration.

Other orders to withhold or withdraw treatment may involve mechanical ventilation, dialysis, nutritional support, hydration, and medications such as antibiotics. The legal and ethical implications of these orders for each patient must be carefully considered. Hospitals should have written policies on all orders to withhold and withdraw treatment. Policies must cover how decisions will be made, who will decide, and what roles the patient, family, health care providers, and the institution will play. Policies must be developed that consider state laws and judicial opinions.