154 Ethanol and Opioid Intoxication and Withdrawal

• Most organ systems in the body can be affected by ethanol consumption. Important associated disease states are electrolyte disturbances, traumatic injuries, infectious diseases, and primary central nervous system, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular complications.

• Ethanol causes depressant effects, but abrupt cessation in long-term users causes hyperstimulation and dangerous withdrawal syndromes.

• Alcohol withdrawal is a spectrum of diseases ranging from minor signs and symptoms, such as anxiety and mild tremor, to severe withdrawal, including autonomic instability and delirium.

• Supportive care is the mainstay of treatment for acute ethanol intoxication and withdrawal. Benzodiazepines constitute the major form of pharmacotherapy for withdrawal syndromes.

• For admitted patients, underlying liver disease, need for intubation, hyperthermia, persistent tachycardia, and use of physical restraints are all associated with increased risk of death in alcohol withdrawal.

• Patients who have a history of major withdrawal and are currently in withdrawal or have significant associated disease states should be admitted for further treatment.

• Brief interventions in alcohol-dependent patients in the emergency department have been shown to have positive effects.

• Opioid intoxication is characterized by depressed central nervous system activity, respiratory depression, and miosis.

• Patients with opioid withdrawal syndrome can present with yawning, piloerection, and mydriasis.

Ethanol

Epidemiology

Ethanol use is a common part of our society, as evidenced by the knowledge that approximately 80% of adults in the United States have consumed ethanol-containing beverages during their lifetimes.1 Mild to moderate consumption (up to one drink/day for women and two drinks/day for men) has been shown to have beneficial cardiovascular effects, including a decreased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, as well as overall decreased mortality (Box 154.1).2–5

Box 154.1

Definition of One Standard Alcoholic Drink

A standard alcoholic drink can be defined as one of the following:

Adapted from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Dietary guidelines for Americans 2005. 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005.

Despite these possibly beneficial effects of alcohol, it has been found to be a top 10 cause of preventable deaths among all age groups in the United States.6 Additionally, approximately 9% of adults meet the diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse and alcoholism.7 This maladaptive behavior can lead to numerous individual medical complications and societal problems, including motor vehicle collisions, assaults, homicide, suicide, and domestic violence. An estimated 7.6 million emergency department (ED) visits per year are for alcohol-related diseases and diagnoses.8

Alcohol withdrawal is seen in the ED in various forms and stages, including early withdrawal, hallucinosis, seizures, and fully developed delirium tremens (DT). DT, a severe withdrawal syndrome defined by the presence of tremors, seizures, and delirium, develops in 5% of patients who develop symptoms of alcohol withdrawal and itself carries a 5% to 15% risk of mortality.9 Among patients admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal, the following clinical features have been found to be associated with an increased risk of death: underlying liver disease, the need for endotracheal intubation, hyperthermia, persistent tachycardia, and the use of physical restraints.10,11

Pathophysiology

Alcohol Intoxication

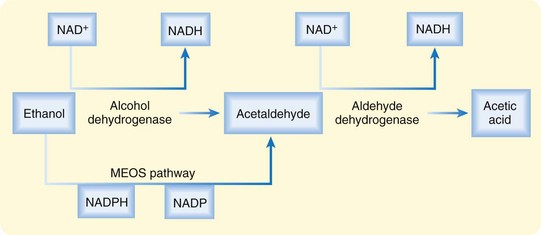

Ethanol is readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and is primarily metabolized by the liver through the alcohol dehydrogenase pathway (Fig. 154.1). Metabolism of ethanol differs in men and women. Although alcohol dehydrogenase is found in gastric mucosa and other tissues, women seem to have less ability to metabolize it by the gastric route.12 Long-term ethanol users or those with high alcohol levels also use a second pathway, the microsomal ethanol-oxidizing system.13

Ethanol is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant involving multiple receptors and pathways. Likely its greatest effect is in enhancing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) inhibitory action.14 Ethanol is also known to block the excitatory N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor, thus leading to further CNS depression.15

The level of CNS depression depends on many factors affecting absorption and elimination, including age, weight, gender, the presence of food, gastric motility, the speed of consumption, and long-term alcohol use. Ethanol intoxication in most states is legally defined as a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 80 to 100 mg/dL (0.08 to 0.1% BAC). Elimination rates vary greatly, but a rate of 20 mg/dL/hour can be assumed for most intoxicated patients in the ED, regardless of initial alcohol level or chronic alcohol use.16,17 Because alcohol follows zero-order kinetics, some sources advocate drawing two ethanol levels to determine the individual patient’s exact rate of ethanol clearance, although this is most often medically unnecessary.

Alcohol Withdrawal

Alcohol withdrawal is best described as a pathologic excitation of the CNS and autonomic systems. GABA receptors are desensitized and downregulated in chronic ethanol use, with a resulting decrease in activity of the inhibitory effects of GABA when a patient reduces ethanol consumption. The excitatory glutamate neurotransmitter system is blocked by the NMDA receptor in the presence of ethanol, and this blockade leads to receptor upregulation in chronic alcoholism and excitation during withdrawal.17 With repeated episodes of alcohol withdrawal, the patient will have more severe withdrawal, a phenomenon known as “kindling.”18 Cessation of alcohol consumption may be inadvertent, as in the patient who is unable to tolerate oral intake because of vomiting or in the hospitalized patient whose access to ethanol is restricted.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Classically, Wernicke encephalopathy consists of the following: ocular abnormalities such as nystagmus and motor palsies, seen in 29% of cases; ataxia, seen in 23% of cases; and mental status change, seen in 82% of cases. Presentations with this classic triad are rare, with only 10% of confirmed cases having all three symptom types.19

Alcohol is related to an estimated 35% of injury-associated ED visits.20 In the setting of trauma, ethanol intoxication generally should not lower the Glasgow Coma Scale score dramatically; whenever a low score is found, further CNS evaluation is warranted.21

Alcohol Withdrawal

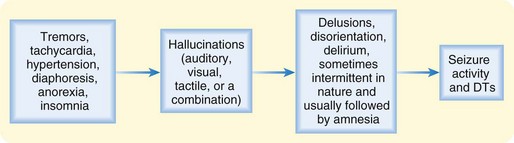

True DT is rare and constitutes the most severe form of withdrawal, although patients may mistakenly equate it with generalized withdrawal syndrome. DT occupies the far end of the spectrum, and it consists of substantial tremor, autonomic hyperactivity, profound confusion, fever, and hallucinations (Fig. 154.2).22

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The diagnosis of ethanol intoxication is mainly one of exclusion, and a history consistent with ethanol consumption is important. The initial approach to the patient should be the same as for any patient with altered mental status. Traumatic injuries and coingestions (acetaminophen, illicit drugs, toxic alcohols) should be high on the differential diagnosis list (Box 154.2).

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

• Incorrectly assuming the patient is intoxicated

• Not suspecting ethanol abuse in an older patient

• Not recognizing concomitant head injury, intoxication, or associated diseases

• Not aggressively treating signs and symptoms of withdrawal

• Inappropriately discharging an acutely intoxicated patient

• Not managing the airway in a timely manner

• Not evaluating for other causes, including head trauma, infection, and cerebrovascular accident, after repeated doses of naloxone or continued altered consciousness in the patient with suspected intoxication or opioid overdose

• Not considering opioid withdrawal in patients with cancer and in other patients with long-term opioid use and treating appropriately

Treatment

Alcohol Intoxication

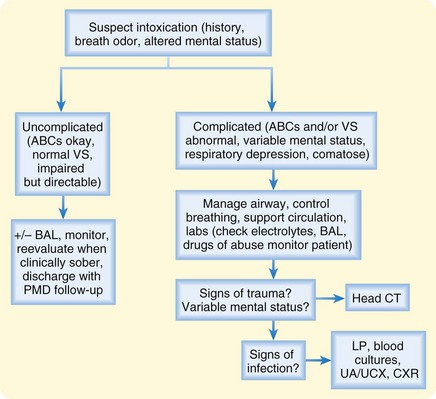

Supportive care is the mainstay of treatment for acute ethanol intoxication (Fig. 154.3). Airway and breathing must be assessed in the comatose patient, and endotracheal intubation, although rarely needed, should be used for airway protection if necessary. Circulation should be assessed, and isotonic intravenous fluids should be given initially for patients with hypotension or volume depletion.

In the comatose patient, naloxone (0.8 mg) should be considered, and glucose (25 to 50 g intravenously) should be given to a hypoglycemic patient. Thiamine (100 mg intravenously) can be given before glucose administration to prevent or treat Wernicke encephalopathy, but glucose administration need not be delayed.23 Electrolyte and thiamine replacement can be achieved orally if the patient is tolerating oral intake, is not at risk of aspiration, and is not being treated for active Wernicke encephalopathy. Routine multivitamin replacement with vitamin B12 and folate in patients presenting with alcohol intoxication is unnecessary.24

Alcohol Withdrawal

Patients who present to the ED with signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal should be evaluated using the Revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA-Ar) scale to aid in determining the severity of withdrawal (Box 154.3). Initial treatment should focus on resuscitation with fluids, replacement of electrolyte deficiencies, and evaluation and treatment of concomitant diseases.

Box 154.3

Alcohol Withdrawal Assessment Scoring Guidelines (Revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Scale)

From Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict 1989;84:1353–7.

Benzodiazepines are the mainstays of treatment for withdrawal and are usually initiated when CIWA-Ar scores are higher than 9. Lorazepam (1 to 4 mg) has an intermediate half-life and is easily used as either an oral, intramuscular, or intravenous agent. The dose can be repeated every 10 minutes as necessary. Other benzodiazepines, such as diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, and midazolam, can also be used. Massive amounts of benzodiazepines have been known to be given to patients in major withdrawal and may be necessary to control rapidly progressive symptoms, although a symptom-triggered approach has been shown to require less medication and shorter treatment.25

Follow-Up, Next Steps of Care, and Patient Education

Patients presenting to the ED with alcohol-related issues should be screened for alcohol abuse and dependence. For patients thought to have or to be at risk for alcohol dependence, brief interventions have been shown to decrease at-risk drinking in the short term and provide an opportunity to provide information on long-term follow-up.26 The brief intervention is described as a four-step conversation with the patient and consists of the following: (1) broach the subject, (2) give feedback on current drinking patterns, (3) discuss readiness to change drinking habits, and (4) provide information. More information on ED-based brief alcohol interventions can be obtained at http://www.ed.bmc.org/sbirt/.

Tips and Tricks

• Serum ethanol measurements are not needed in every patient. Obtain an ethanol measurement when needed for confirmation or to guide treatment.

• Remember to rule out any other disease process in the patient with complicated ethanol intoxication.

• Discharge time can be guided by the following: (1) a calculated sober time according to ethanol level; (2) an evaluation for clinical sobriety; or (3) whether the patient is awake and directable and will be in the care of a responsible, sober adult.

• Calculate sober time as follows: (1) subtract 80 to 100 (legal limit) from the blood ethanol level; (2) divide the remainder by 20 (mg/dL/hr); the resulting number is the time to sobriety in hours.

• Opioids may have a long half-life, so additional naloxone doses may be necessary if the patient seems to return to a depressed state after initially responding to naloxone.

• In patients with cancer or long-term pain medication use who present with symptoms of opioid withdrawal, treatment of nausea and vomiting and a dose of the prescribed opioid medications are appropriate.

Opioids

Epidemiology

Opioids are a class of drugs that comprise natural, semisynthetic, and synthetic substances that provide analgesic and anesthetic properties by acting at opioid receptors. Box 154.4 gives the definition of terms associated with opioids. Opioids are most commonly used in the ED for the treatment of acute pain and for procedural sedation, although ED visits for patients with chronic opioid use for both medical and nonmedical reasons have steadily increased since 2000.27 Between 2004 and 2008, the number of ED visits for nonmedical uses of prescription opioids increased by 111% and now is equivalent to the number of visits associated with illicit drugs.28 This change parallels the marked increase in opioid prescription rates seen since 2000; approximately 4 million patients in the United States are receiving long-acting, long-term opioid therapy.29

Box 154.4 Definition of Terms Commonly Related to Opioids

Opium: A resin from opium poppies (flowers) containing morphine, codeine, and thebaine

Opiate: Only the narcotic alkaloids directly found in opium (morphine, codeine, thebaine)

Opioid: Natural, semisynthetic, and synthetic opium derivatives that bind opioid receptors

Narcotic: Compounds with sedative properties, commonly including the opioids; in legal jargon, term referring to a controlled substance with illicit use

Tolerance: Physiologic adaptation to opioid use with escalating doses required for similar effects

Dependence: Continuous use despite negative impacts on life in addition to tolerance, withdrawal history, and compulsive use

Withdrawal: Physiologic response to decreased intake of opioids in dependent individuals with behavioral, cognitive, and physical changes

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Respiratory depression leading to apnea is the primary life-threatening presentation of opioid overdose. Because respiratory depression is reliably accompanied by altered mental status or coma, a history of opioid use is often not readily available and should be considered in patients who are found unconscious and who have a decreased respiratory rate or miosis. Patients with milder opioid intoxication may present with nausea, vomiting, constipation, miosis, depressed CNS level, and depressed respiratory status. Table 154.1 contains a more extensive list of these symptoms.

Table 154.1 Opioid Intoxication and Withdrawal Signs and Symptoms by Organ System

| OPIOID INTOXICATION | OPIOID WITHDRAWAL | |

|---|---|---|

| Central nervous system | Depression of activity Respiratory depression Increased parasympathetic activity |

Excitation, restlessness, anxiety, seizures (rare) Tachypnea Adrenergic/sympathetic overdrive (lacrimation, piloerection, yawning, diaphoresis) |

| Head and neck | Miosis (pinpoint pupils) Antitussive effect |

Mydriasis Rhinorrhea |

| Cardiovascular system | Hypotension to normal blood pressure Bradycardia to normal heart rate |

Normal blood pressure to hypertension Normal heart rate to tachycardia |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Constipation Nausea and vomiting |

Diarrhea Nausea and vomiting |

| Genitourinary tract | Sphincter constriction/spasm | Sphincter relaxation |

| Musculoskeletal system | Relaxation and flaccidity | Myalgias |

| Psychiatric manifestations | Euphoria or dysphoria | Drug craving |

Certain opioids have unique toxicities that must be considered during ED evaluation (Table 154.2). Methadone, an agent used primarily for addiction therapy, is very long acting, with a half-life of more than 24 hours, and can cause prolongation of the QTc interval and torsades de pointes. Propoxyphene, tramadol, and meperidine may cause seizures, even in therapeutic doses. Propoxyphene was taken off the market because of its tricyclic antidepressant–like sodium channel activity and association with wide complex tachyarrhythmias and negative inotropy, even at therapeutic doses. Fentanyl, particularly when given as a rapid injection, can cause chest wall rigidity that can be difficult to manage, even with naloxone and endotracheal intubation.30

Table 154.2 Specific Opioid Toxicities

| COMPOUND | TOXICITY |

|---|---|

| Morphine | Acute lung injury |

| Meperidine | Seizures |

| Methadone | QTc prolongation, torsades de pointes |

| Fentanyl | Chest wall rigidity |

| Propoxyphene | QRS prolongation, seizures |

| Tramadol | Seizures |

Adapted from Gutstein HB, Akil H. Opioid analgesics. In: Brunton LL, editor. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema is an uncommon complication of opioid overdose characterized by hypoxia despite resolution of altered mental status and bradypnea, production of frothy pink sputum, and chest radiograph evidence of diffuse pulmonary infiltrates.31 Opioid-related pulmonary edema is short-lived and infrequently requires intubation, but it mandates admission to the hospital until resolution of symptoms and hypoxia. In the alert patient, noninvasive ventilation can be considered for improved oxygenation.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis of mild opioid intoxication should include diagnoses that cause altered mental status and hypoventilation: hypoglycemia, head injury, and overdose of other medications (alcohols, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, tricyclic antidepressants). The differential diagnosis for the patient who is ill secondary to opioid overdose is similar to that for the patient in coma; infection, cerebrovascular accident, head trauma, and other overdoses should be considered (Box 154.5).

Follow-Up, Next Steps of Care, and Patient Education

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Physical Examination

• Stable or unstable vital signs (including repeat evaluation)?

• Does the patient look ill? Are signs of trauma present?

• Is the patient awake? Arousable? What is the Glasgow Coma Scale score?

• Respiratory and airway status

• Skin and musculoskeletal findings

• Eye examination: pinpoint pupils

• Findings of any repeat examinations made while the patient is in the emergency department

• Signs of intoxication at admission and discharge, especially if ethanol level was not measured

Patient Instructions

• Discussion with patient regarding diagnosis, warning signs, what to do, follow-up, when to return

• Referral to outpatient primary medical follow-up and substance abuse centers

• For pediatric accidental ingestions: poison prevention counseling and child protective service notification if indicated

Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1117–1121.

Holahan CJ, Schutte KK, Brennan PL, et al. Late-life alcohol consumption and 20-year mortality. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1961–1971.

Monte R, Rabunal R, Casariego E, et al. Analysis of the factors determining survival of alcoholic withdrawal syndrome patients in a general hospital. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:151–158.

Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1981–1985.

Pitzele HZ, Tolia VM. Twenty per hour: altered mental state due to ethanol abuse and withdrawal. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:683–705.

1 Pleis JR, Lucas JW, Ward BW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. Vital Health Stat 10. 2009;249:1–157.

2 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Dietary guidelines for Americans 2005, 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005.

3 Thun MJ, Peto R, Lopez AD, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality among middle-aged and elderly U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1705–1714.

4 Berger K, Ajani UA, Kase CS, et al. Light-to-moderate alcohol consumption and risk of stroke among U.S. male physicians. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1557–1564.

5 Holahan CJ, Schutte KK, Brennan PL, et al. Late-life alcohol consumption and 20-year mortality. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1961–1971.

6 Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 6, 2009. e1000058

7 Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, et al. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234.

8 McDonald AJ, 3rd., Wang N, Camargo CA, Jr. US emergency department visits for alcohol-related diseases and injuries between 1992 and 2000. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:531–537.

9 Tetrault JM, O’Connor PG. Substance abuse and withdrawal in the critical care setting. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24:767–788. viii

10 Monte R, Rabunal R, Casariego E, et al. Analysis of the factors determining survival of alcoholic withdrawal syndrome patients in a general hospital. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:151–158.

11 Khan A, Levy P, DeHorn S, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with delirium tremens. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:788–790.

12 Frezza M, di Padova C, Pozzato G, et al. High blood alcohol levels in women: the role of decreased gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity and first-pass metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:95–99.

13 Norberg A, Jones AW, Hahn RG, et al. Role of variability in explaining ethanol pharmacokinetics: research and forensic applications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:1–31.

14 Kumar S, Porcu P, Werner DF, et al. The role of GABA(A) receptors in the acute and chronic effects of ethanol: a decade of progress. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;205:529–564.

15 Krystal JH, Petrakis IL, Krupitsky E, et al. NMDA receptor antagonism and the ethanol intoxication signal: from alcoholism risk to pharmacotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:176–184.

16 Brennan DF, Betzelos S, Reed R, et al. Ethanol elimination rates in an ED population. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13:276–280.

17 Pitzele HZ, Tolia VM. Twenty per hour: altered mental state due to ethanol abuse and withdrawal. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:683–705.

18 Duka T, Gentry J, Malcolm R, et al. Consequences of multiple withdrawals from alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:233–246.

19 Cook CC, Hallwood PM, Thomson AD. B vitamin deficiency and neuropsychiatric syndromes in alcohol misuse. Alcohol Alcohol. 1998;33:317–336.

20 Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y. Trends in alcohol- and drug-related ED and primary care visits: data from three US national surveys (1995-2005). Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:576–583.

21 Stuke L, Diaz-Arrastia R, Gentilello LM, et al. Effect of alcohol on Glasgow Coma Scale in head-injured patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245:651–655.

22 Turner RC, Lichstein PR, Peden JG, Jr., et al. Alcohol withdrawal syndromes: a review of pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:432–444.

23 Krishel S, SaFranek D, Clark RF. Intravenous vitamins for alcoholics in the emergency department: a review. J Emerg Med. 1998;16:419–424.

24 Li SF, Jacob J, Feng J, et al. Vitamin deficiencies in acutely intoxicated patients in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:792–795.

25 Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1117–1121.

26 Academic Emergency Department Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral for Treatment Research Collaborative. The impact of screening, brief intervention and referral for treatment in emergency department patients’ alcohol use: a 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:514–519.

27 Braden JB, Russo J, Fan MY, et al. Emergency department visits among recipients of chronic opioid therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1425–1432.

28 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of selected prescription drugs: United States, 2004-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:705–709.

29 Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1981–1985.

30 Fahnenstich H, Steffan J, Kau N, et al. Fentanyl-induced chest wall rigidity and laryngospasm in preterm and term infants. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:836–839.

31 Sporer KA, Dorn E. Heroin-related noncardiogenic pulmonary edema: a case series. Chest. 2001;120:1628–1632.