CHAPTER 2

Esophagus

INTRODUCTION

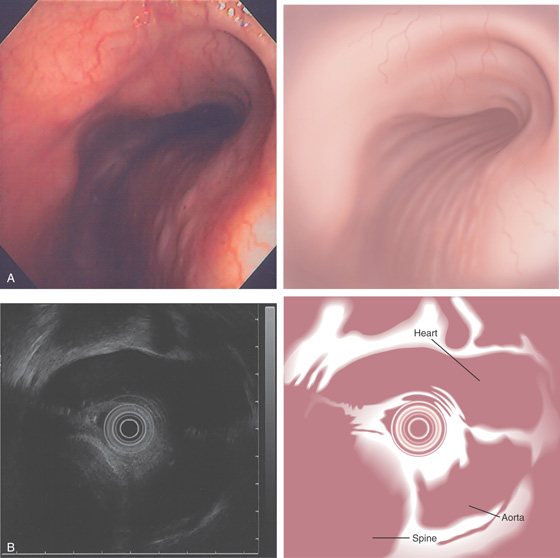

The esophagus is a muscular tube 20 to 23 cm in length, functioning as a conduit from the oropharynx to the stomach. It begins at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra and at approximately 15 to 17 cm on the standard endoscope. Endoscopically, it is characterized by a whitish color typical for squamous mucosa. Along the course of the esophagus, impressions from the trachea and aortic arch may be identified. Mediastinal abnormalities may also manifest in the esophagus. The gastroesophageal (GE) junction is located 38 to 40 cm from the incisors and is easily recognized. A more proximal location of the junction suggests a hiatal hernia or Barrett’s esophagus. The most common esophageal abnormalities encountered by endoscopists relate to reflux disease and its complications, primary neoplasms, and opportunistic infections.

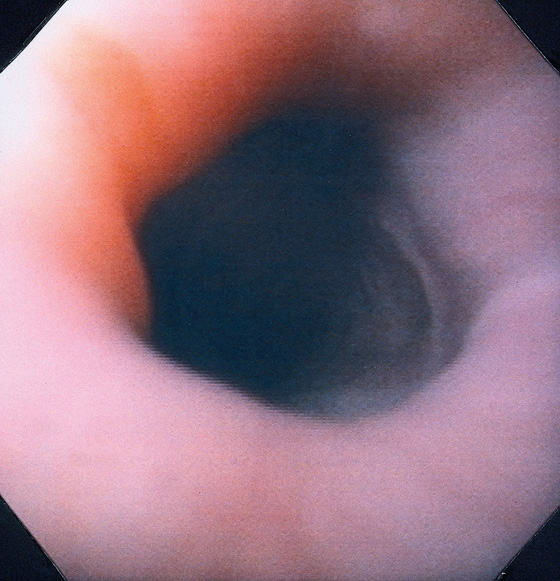

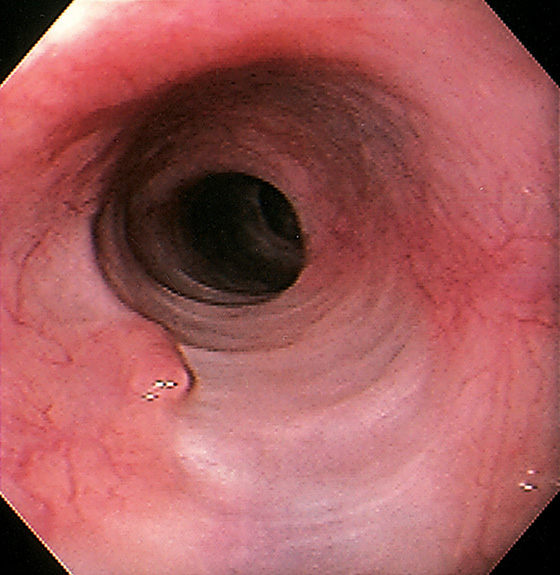

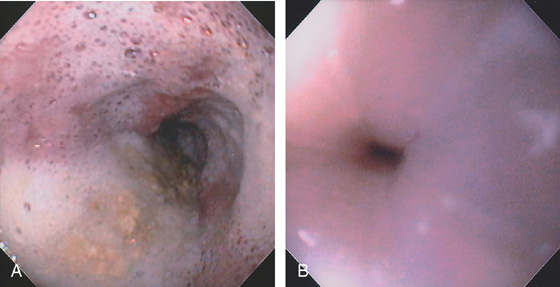

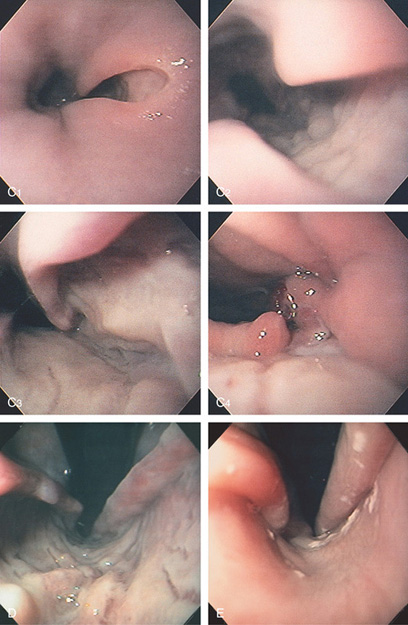

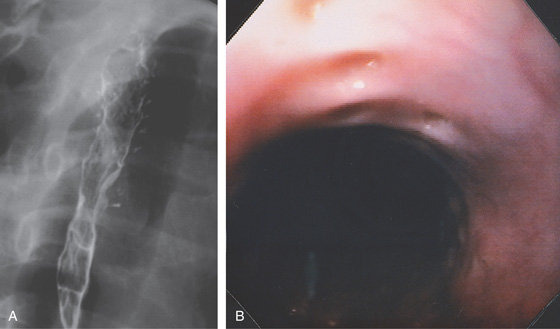

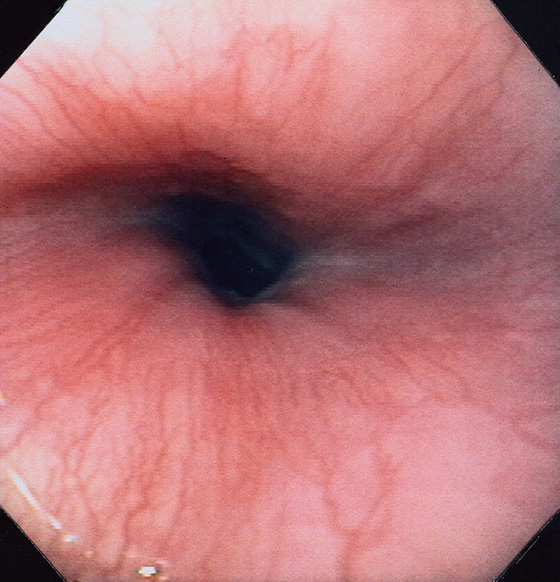

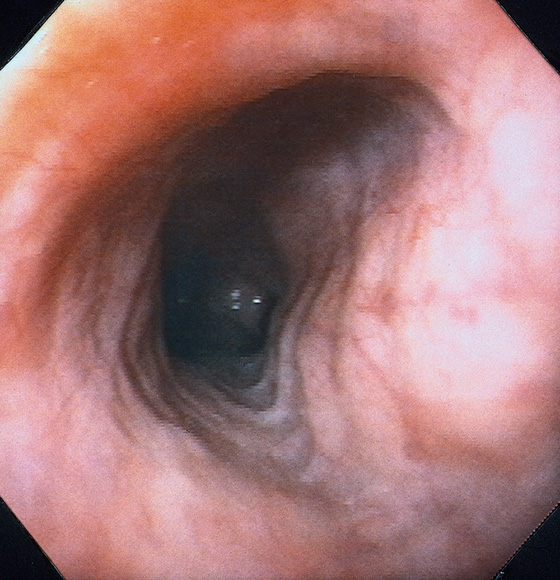

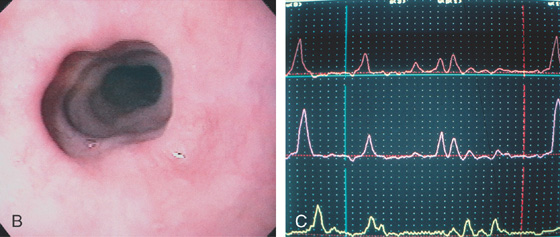

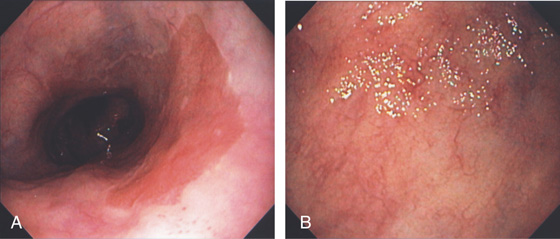

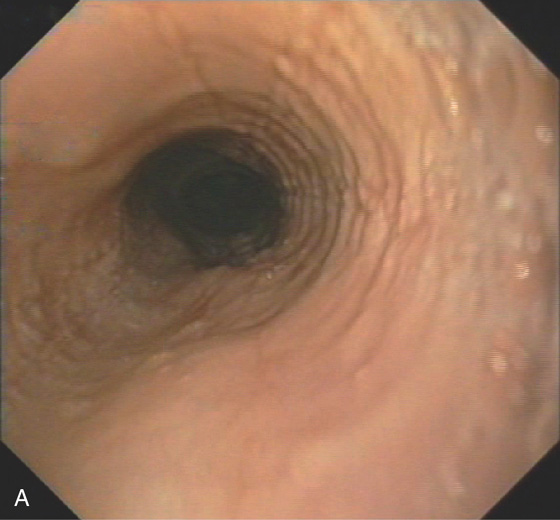

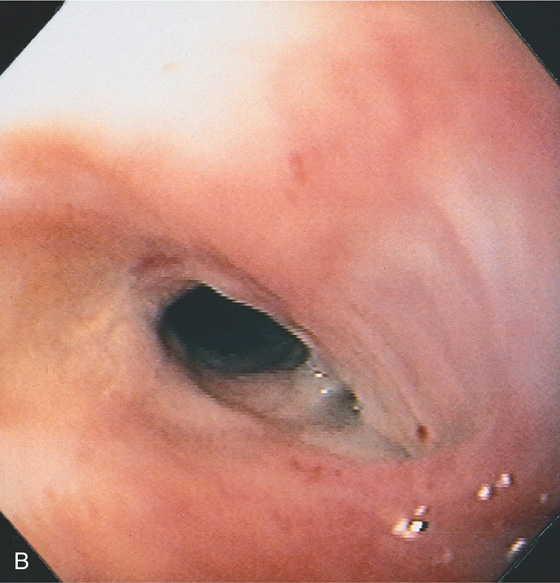

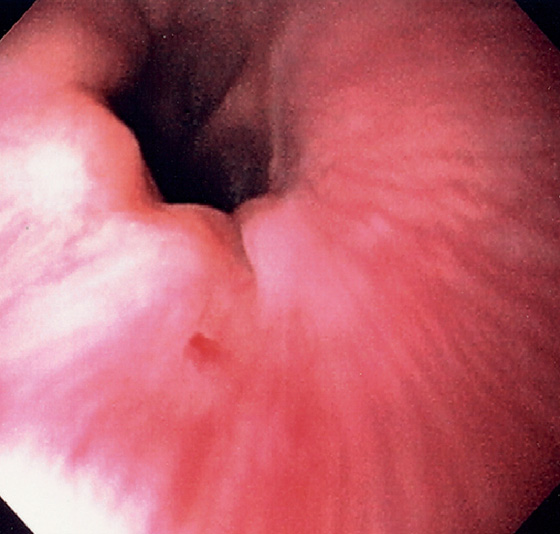

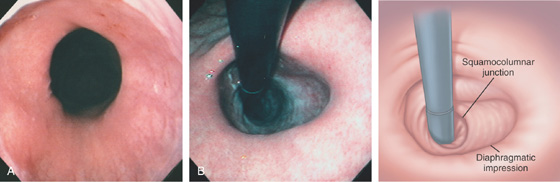

Figure 2.1 UPPER ESOPHAGEAL SPHINCTER

The cricopharyngeus muscle is contracting. The proximal esophagus is in the distance.

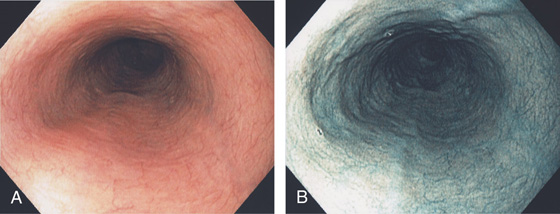

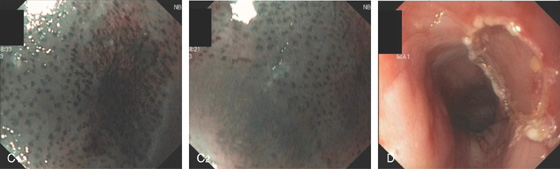

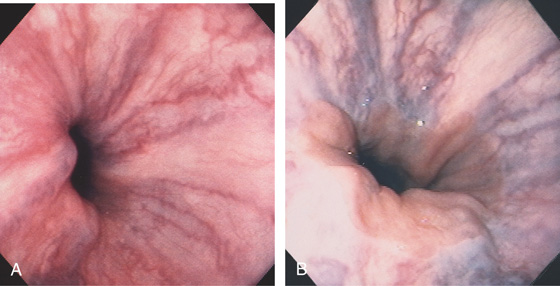

Figure 2.2 MIDESOPHAGUS

The esophageal mucosa has a whitish appearance with a delicate vascular pattern (A) highlighted by narrow band imaging (B).

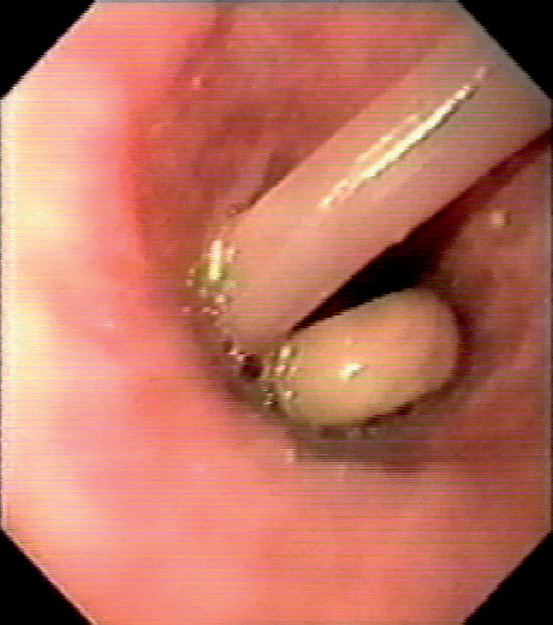

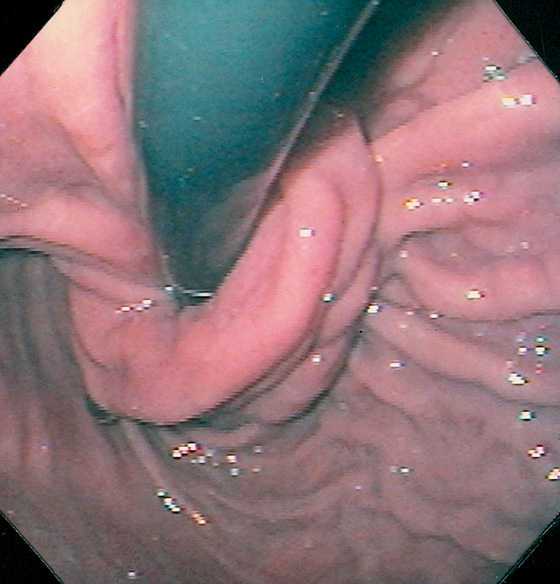

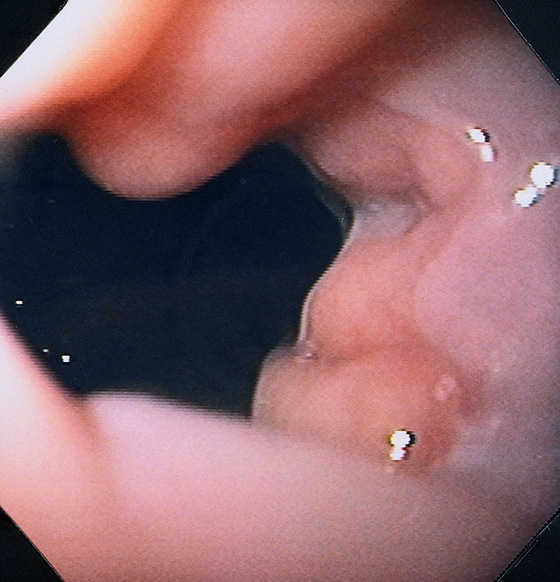

Figure 2.3 VASCULAR PATTERN AT THE GASTROESOPHAGEAL JUNCTION

Multiple linearly arranged blood vessels are present proximal to the gastroesophageal junction.

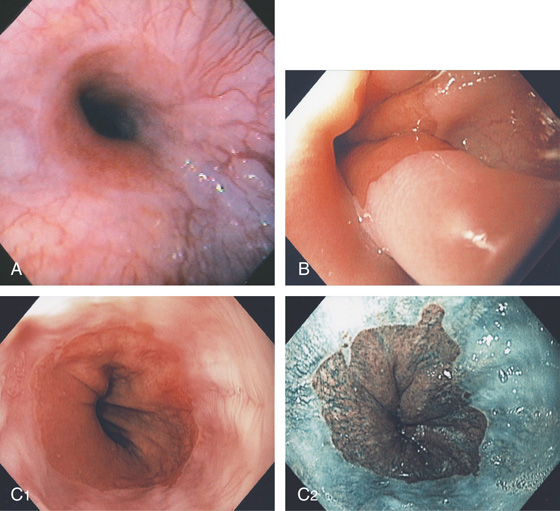

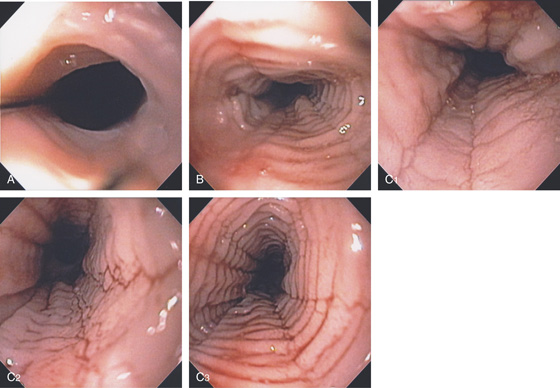

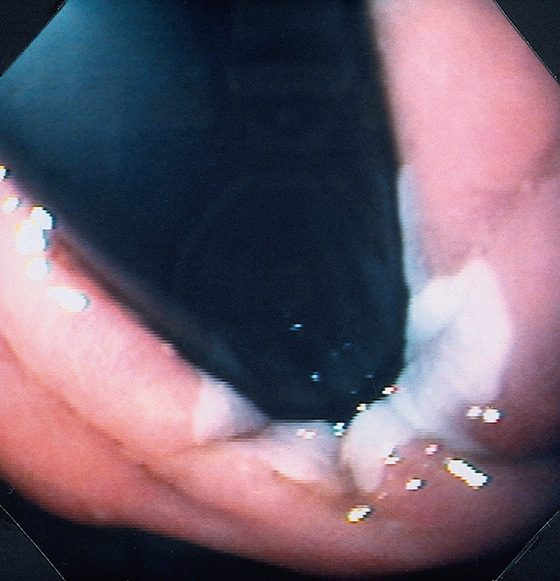

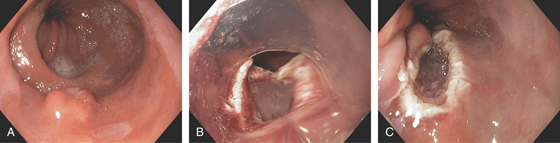

Figure 2.4 GASTROESOPHAGEAL JUNCTION

A, The squamous mucosa and blood vessels end abruptly with a well-demarcated margin. The orange mucosa of the stomach is opposite the esophageal mucosa. B, Note the crisp distinction between the squamous mucosa and the orange appearance of the gastric mucosa. In this case, a paucity of blood vessels appears in the distal esophageal mucosa. C1, C2, The gastroesophageal junction is well delineated by narrow band imaging.

Figure 2.5 GASTROESOPHAGEAL JUNCTION WITH OPENING OF THE LOWER ESOPHAGEAL SPHINCTER

The normal demarcation between the white squamous mucosa and pinkish orange gastric mucosa.

Figure 2.6 RETROFLEX VIEW OF THE GASTROESOPHAGEAL JUNCTION

Retroflexion demonstrates demarcation of the gastroesophageal junction, where squamous mucosa can be seen encircling the endoscope.

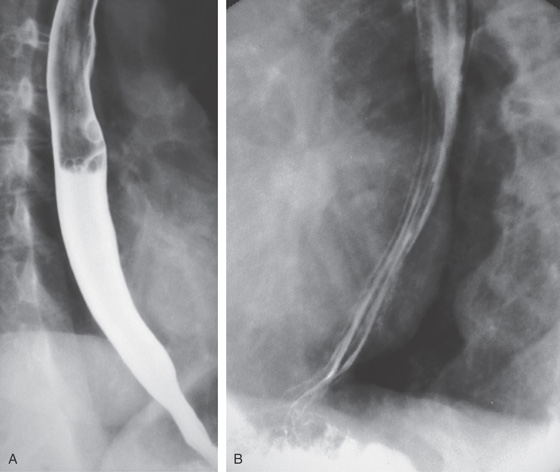

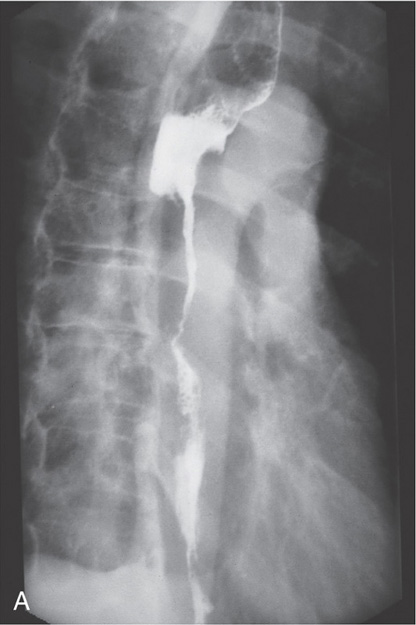

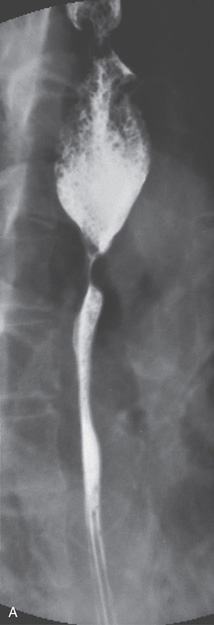

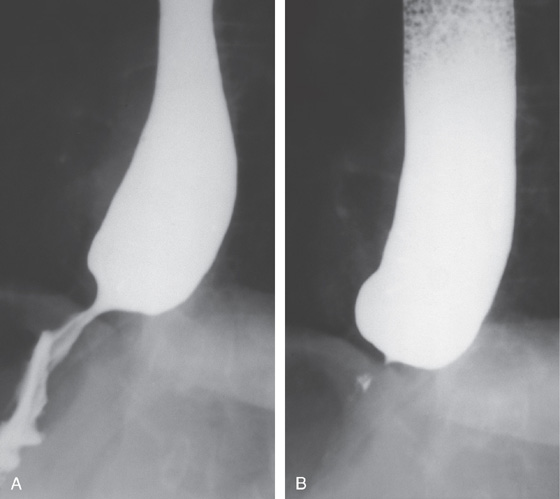

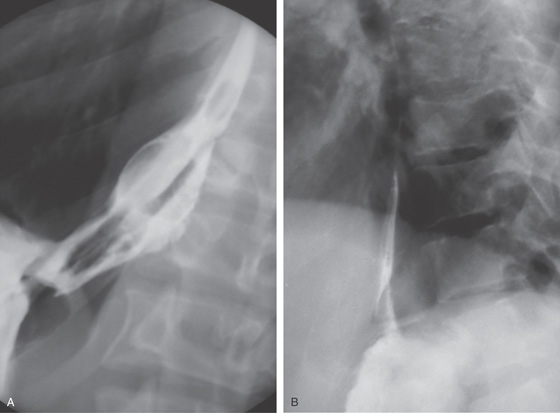

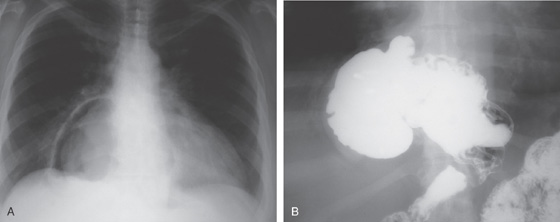

Figure 2.7 BARIUM ESOPHAGRAM

A, Barium esophagram shows normal esophageal contour and luminal diameter. The esophageal mucosa is proximal to the barium column. The esophageal walls are smooth and symmetric. Air bubbles are present at the proximal column of barium. The esophagus can be seen entering the stomach at the gastric air bubble. B, With the esophagus collapsed, the esophageal folds are delicate and smooth.

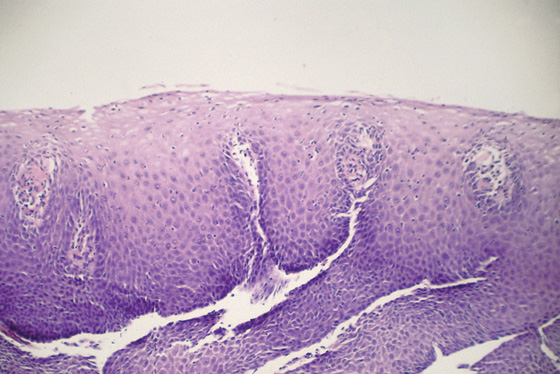

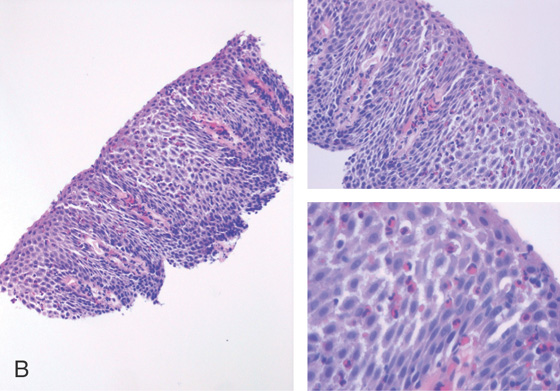

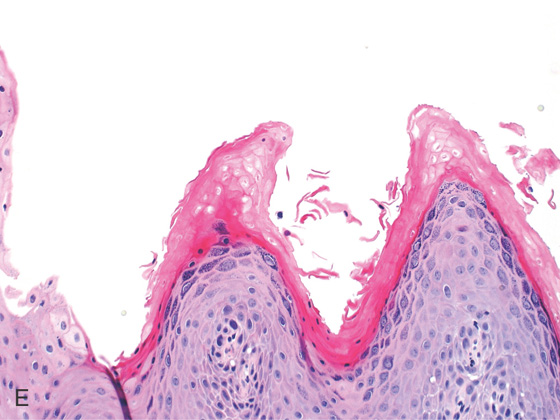

Figure 2.8 NORMAL STRATIFIED SQUAMOUS EPITHELIUM

Vascular channels are seen in the epithelium. Portions of the basal epithelium are present.

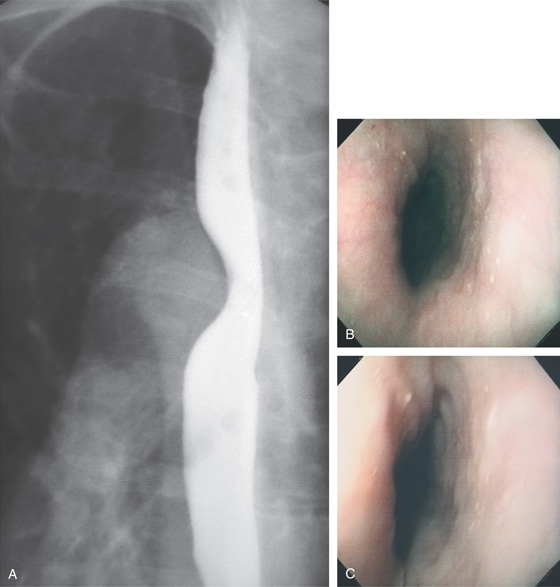

Figure 2.9 TRACHEAL IMPRESSION

Tracheal impression on the proximal esophagus.

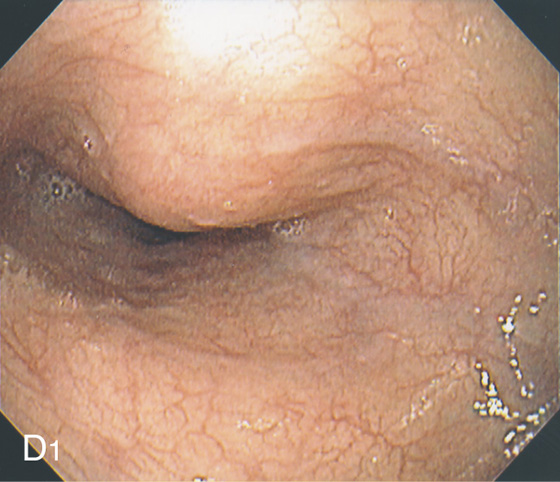

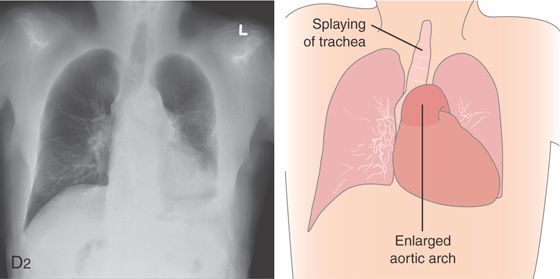

Figure 2.10 AORTIC IMPRESSION

A, Indentation on the midesophagus from an ectatic aorta. The indentation is smooth and unilateral. B, The normal diameter of the esophageal mucosa is diminished by extrinsic compression; the overlying mucosa is normal. C, With systole, the esophageal lumen is further compressed. D1, Extrinsic compression in the proximal midesophagus. D2, Chest x-ray film demonstrates splaying of the trachea with an enlarged aortic arch. L indicates the left side.

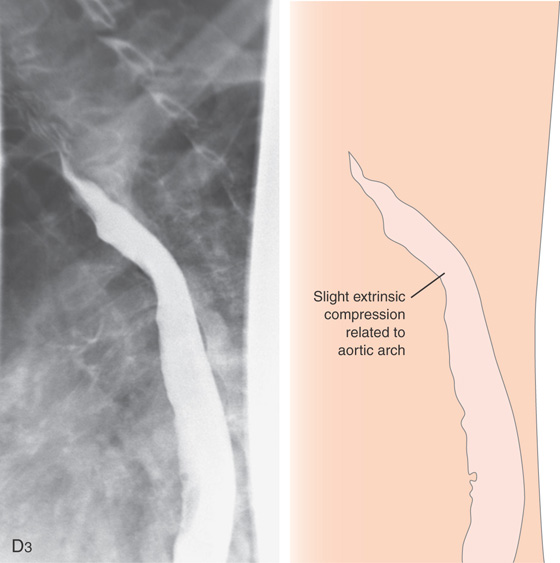

Figure 2.10 AORTIC IMPRESSION

D3, Barium swallow shows slight extrinsic compression related to the aortic arch.

Figure 2.11 AORTIC IMPRESSION

A, Extrinsic compression posteriorly in the midesophagus. Erosions are present on the lesion. B, The contrast-filled esophagus is compressed posteriorly by an ectatic aorta.

Figure 2.12 TERTIARY ESOPHAGEAL CONTRACTIONS

A, Multiple tertiary contractions observed in a patient with dysphagia.

B, Tertiary contractions occur during endoscopy as well. C, Simultaneous contractions on esophageal manometry.

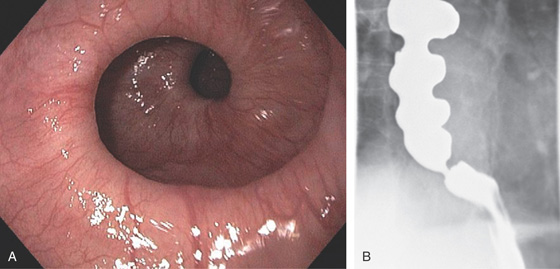

Figure 2.13 CORKSCREW ESOPHAGUS

A, Endoscopic images show circular folds resembling a corkscrew. B, Corresponding barium esophagram.

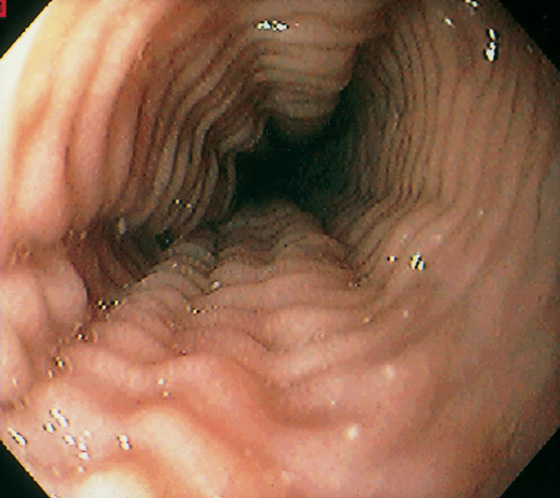

Figure 2.14 FELINE ESOPHAGUS

Multiple simultaneous smooth muscle contractions result in this ringlike appearance.

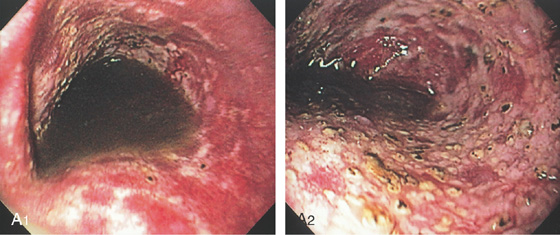

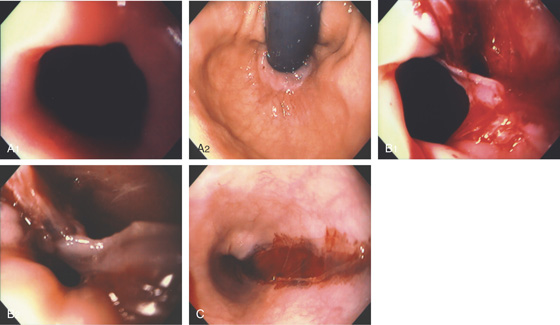

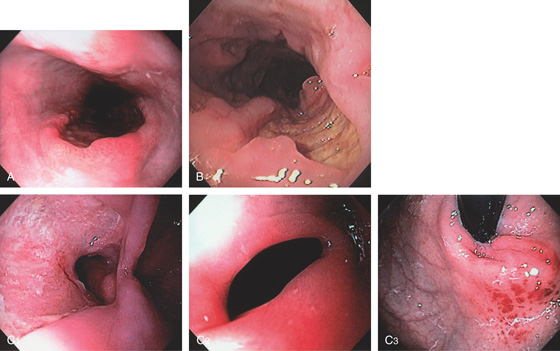

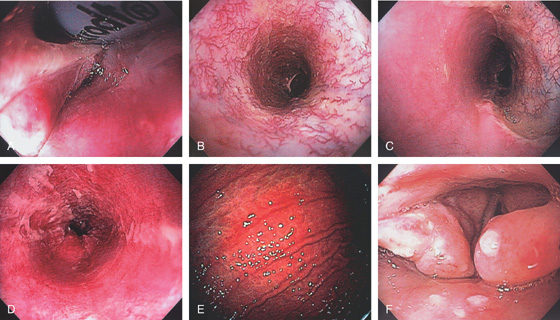

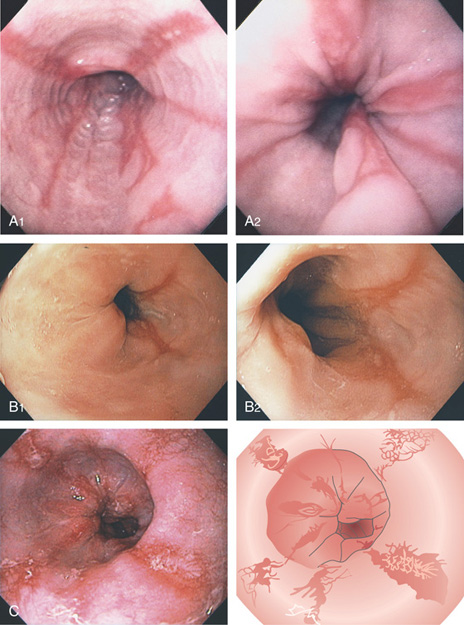

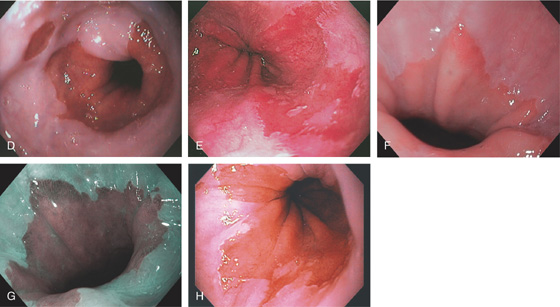

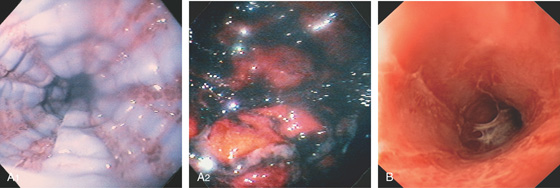

Figure 2.15 GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GERD)

A1, Typical appearance of erosive esophagitis, with linear erythematous streaks and central ulceration emanating from the gastroesophageal junction. Between the lesions, the squamous epithelium is normal. A2, With the lumen collapsed, the ulcerations reside primarily on the surface of the normal esophageal folds. B1, B2, Typical linear ulcerations emanating from the gastroesophageal junction. C, Multiple linear ulcerations in the typical pattern.

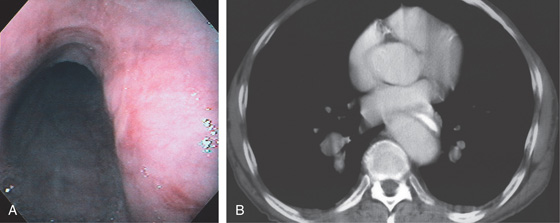

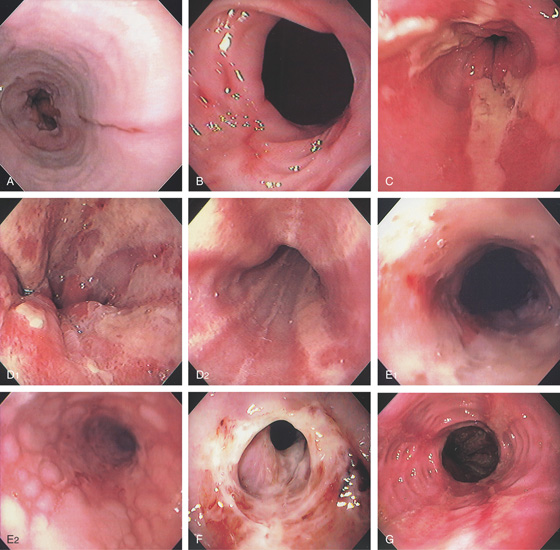

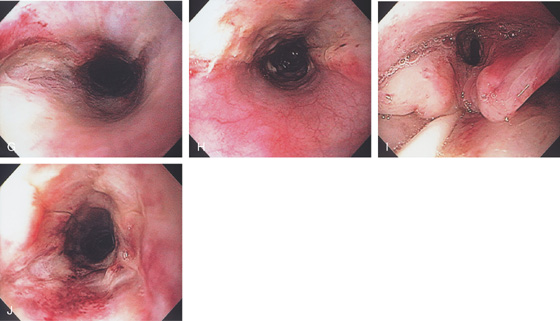

Figure 2.16 GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

A, Single linear erosion in the distal esophagus. B, Erythematous erosions at the GE junction. Note the patulous sphincter. C, Streaks of exudate in the distal esophagus. D1, Exudate at the GE junction, which is almost confluent. D2, More proximally, the exudate takes on a linear migration typical for GERD. E1, Circumferential ulceration at the GE junction above a patulous sphincter. E2, More proximally, the mucosa takes on the appearance of multiple, well-circumscribed, squamous “islands” caused by edema with intervening mucosal erosion. F, Circumferential ulcer with fresh bleeding and luminal narrowing above a patulous GE junction. G, Patulous GE junction above a hiatal hernia associated with multiple scars from prior disease. Note the linear erosions.

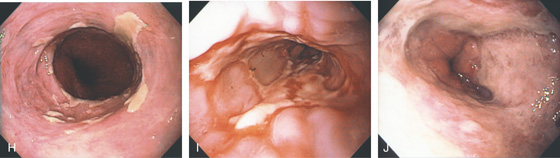

Figure 2.16 GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

H, Note that some of the exudate has a plaquelike appearance in this patient with a patulous GE junction and hiatal hernia. I, The exudate and ulceration have coalesced. The mucosa has a nodular appearance. J, Note the circumferential ulceration ends abruptly at the GE junction.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (Figure 2.16)

Infection

Cytomegalovirus

Herpes simplex virus

Other infections

Pill-induced esophagitis

Caustic ingestion

Figure 2.17 GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

A, The linear ulcers are becoming circumferential and deep. The gastroesophageal junction seen in the distance is patulous, and the proximal portion of a hiatal hernia is present. B, Severe disease with circumferential ulceration, overlying exudate, and loss of the normal mucosal pattern. The diffuse abnormality extends proximally from the normal-appearing gastroesophageal junction.

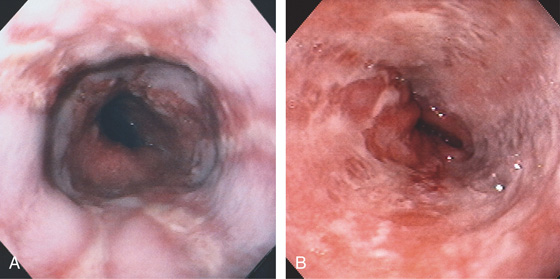

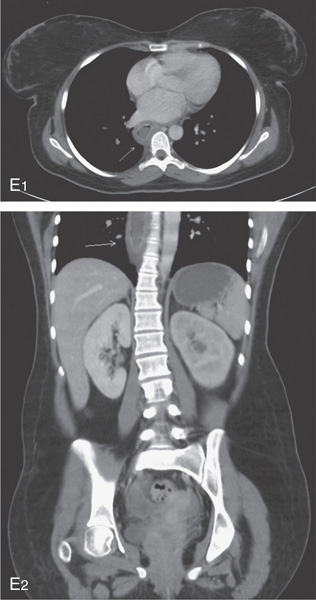

Figure 2.18 SEVERE GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

A, Narrowing in the distal esophagus associated with circumferential ulceration. B, More proximally the ulceration is hemicircumferential. C, In the midesophagus, the ulceration takes on the typical linear ulceration. D, Near the upper esophageal sphincter, no exudate is present, but erythema and evidence of scarring exist.

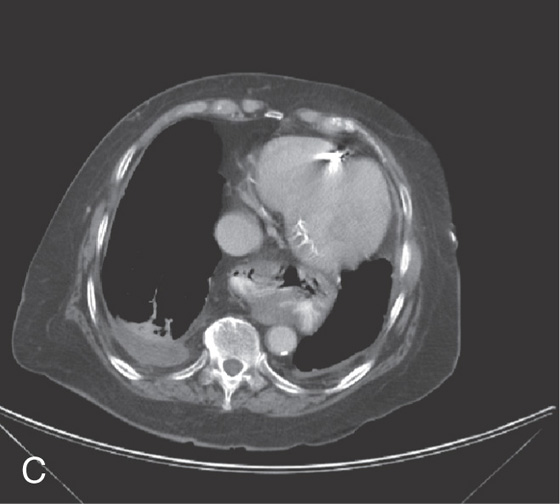

E1, E2, Esophageal wall thickening on CT scan.

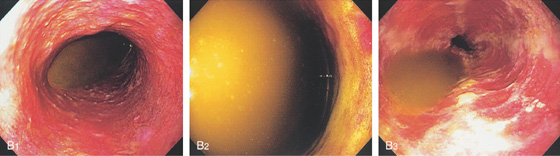

Figure 2.19 SEVERE ESOPHAGITIS ASSOCIATED WITH GASTRIC OUTLET OBSTRUCTION

A1, Gastric bile stained fluid present in the distal esophagus. A2, After aspiration, the diffuse nodularity and ulceration are evident.

B1, Bilious fluid is present in the distal esophagus associated with erosions. B2, The stomach is full of bilious fluid because of pyloric obstruction. B3, After aspiration of the fluid, severe erosive esophagitis is evident.

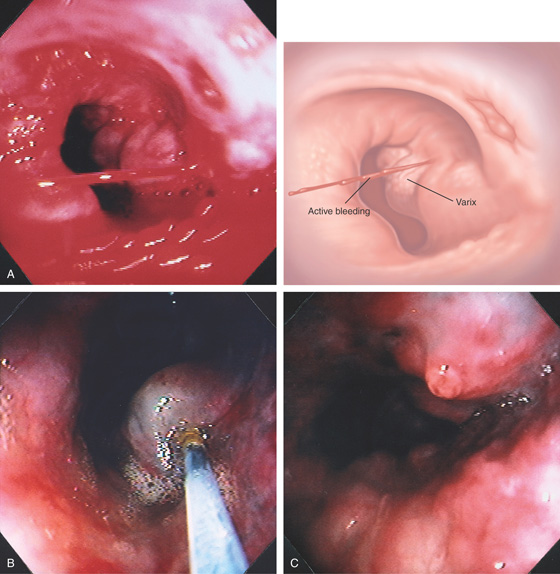

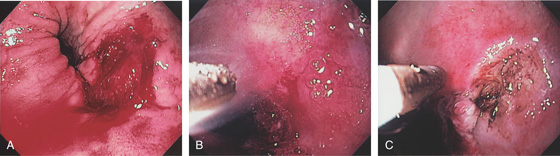

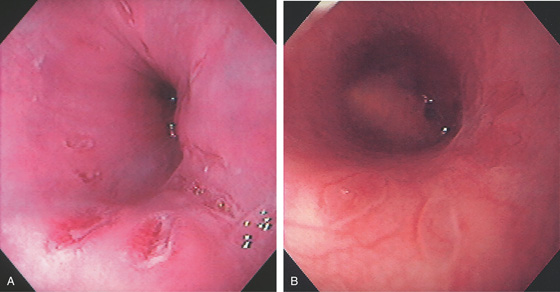

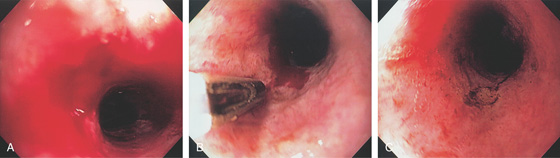

Figure 2.20 BLEEDING GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

A, Arterial bleeding in the distal esophagus. B, Thermal probe applied to the area of bleeding. Note the circumferential erosive esophagitis. C, Hemostasis achieved with a coagulation “footprint” remaining.

Figure 2.21 IRREGULAR Z LINE

A, Irregular squamocolumnar junction associated with a hiatal hernia. B, Irregular squamocolumnar junction associated with a hiatal hernia. C, Mild narrowing at the GE junction suggestive of a ring above a hiatal hernia. Note the patches of gastric mucosa above the ringlike structure. This may suggest patches of Barrett’s mucosa. D, Biopsy confirms gastric cardia mucosa without specialized intestinal epithelium.

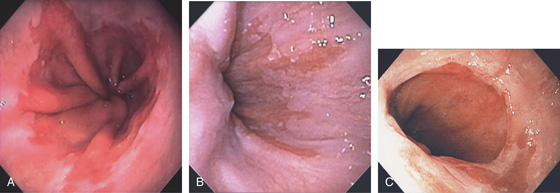

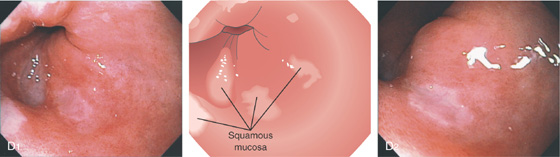

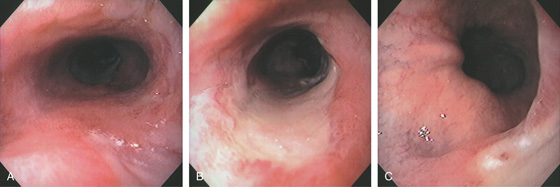

Figure 2.22 BARRETT’S ESOPHAGUS

A, Typical-appearing Barrett’s mucosa emanating from the GE junction. B, Tongue of Barrett’s mucosa with a small squamous island. C, Two tongues of Barrett’s mucosa extending from the GE junction. D, Normal squamous mucosa (left) with gastric epithelium. Goblet cells are present in the gastric epithelium, indicating intestinal metaplasia. E, The goblet cells are highlighted with Alcian blue staining. The large vacuoles are purple blue.

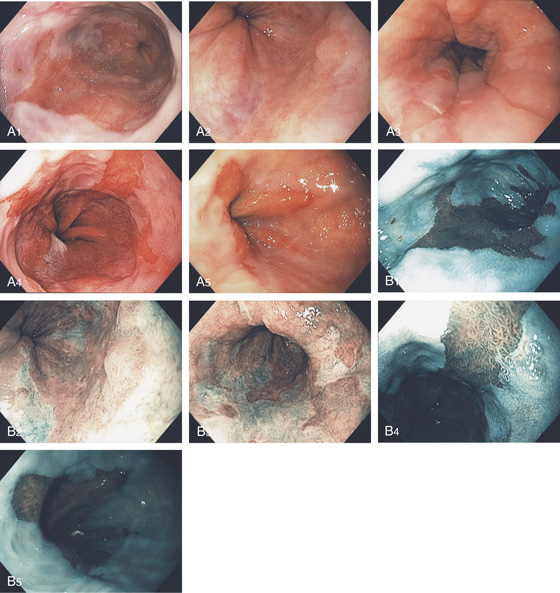

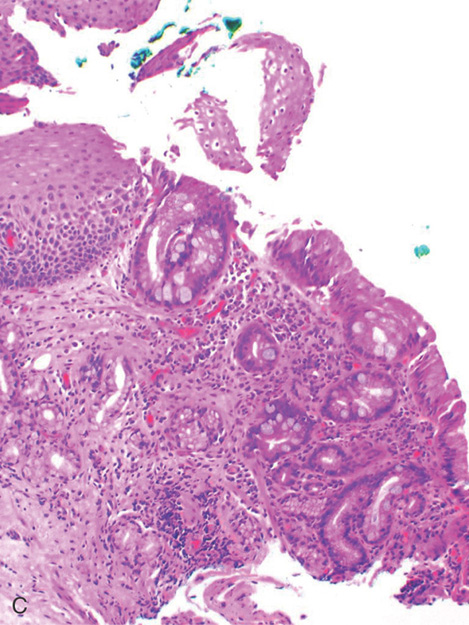

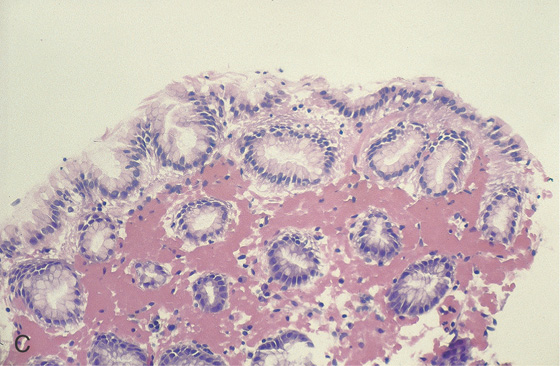

Figure 2.23 BARRETT’S MUCOSA

A1-A5, Typical tongues of Barrett’s mucosa of variable lengths emanating from the gastroesophageal junction. B1-B5, The Barrett’s mucosa is well delineated by narrow band imaging. C, Biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction shows squamous tissue, as well as columnar-lined intestinal mucosa with plentiful goblet cells.

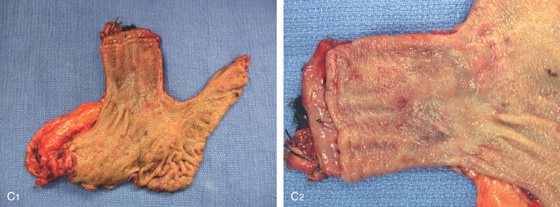

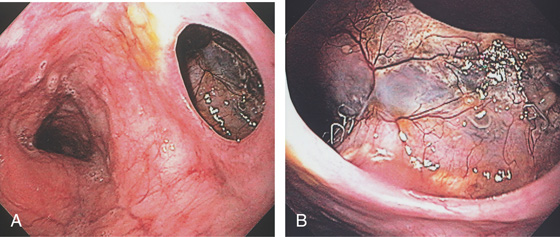

Figure 2.24 BARRETT’S MUCOSA WITH SQUAMOUS ISLAND

A, Long-segment Barrett’s mucosa with island of squamous mucosa. B, Barrett’s segment between squamous mucosa. The Barrett’s mucosa shows dysplasia.

C1, C2, Postoperative specimen shows the long-segment Barrett’s mucosa.

D1, D2, Several areas of squamous mucosa are identified in the Barrett’s mucosa.

Figure 2.25 LONG-SEGMENT BARRETT’S ESOPHAGUS

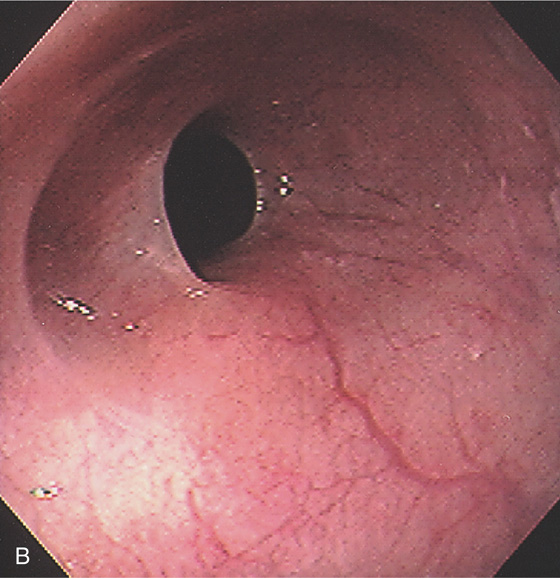

A, Long segment of Barrett’s esophagus extending from the GE junction. B, Note the mucosa has a pale appearance with visible blood vessels.

Figure 2.26 SHORT-SEGMENT BARRETT’S ESOPHAGUS

A, Short tongue of Barrett’s mucosa at the GE junction. B, Short-segment Barrett’s mucosa extending just proximal to the GE junction. Note the two associated small Barrett’s patches. C, Small patch of Barrett’s mucosa that appears distinct from the GE junction.

D, Circumferential short-segment Barrett’s mucosa with an additional associated patch. E, Areas of short-segment Barrett’s mucosa above a hiatal hernia. F, Short-segment Barrett’s mucosa as seen by high-definition endoscopy. G, Narrow band imaging also shows a short segment of Barrett’s mucosa. H, Several areas of Barrett’s mucosa above a hiatal hernia proximal to the most proximal portion of the gastric folds.

Figure 2.27 BARRETT’S ULCER

A, Ulceration with heaped-up margins in the distal esophagus. B, The ulceration becomes circumferential distally and has a black base, indicating necrosis. The gastroesophageal junction appears in the distance. C1, Occasional goblet cells indicate Barrett’s metaplasia of the intestinal type. C2, Ulcerative esophagitis with granulation tissue and gastric epithelium.

Figure 2.28 BARRETT’S ULCER

A, Proximal extent of long-segment Barrett’s mucosa to the midesophagus. B, Long midesophageal ulcer on a background of Barrett’s mucosa. C, The ulcer extends to but does not involve the GE junction. Note the surrounding Barrett’s mucosa.

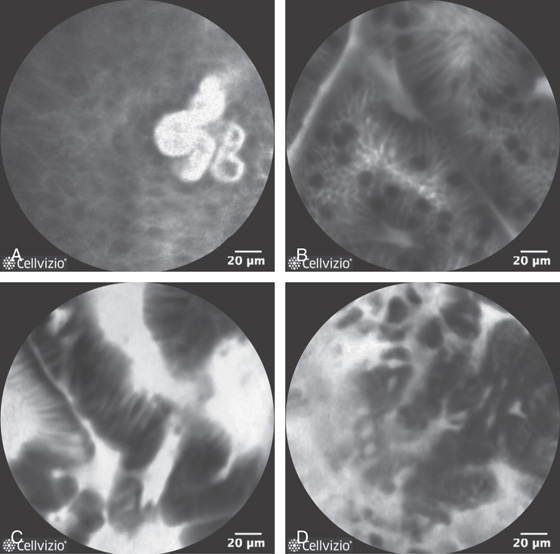

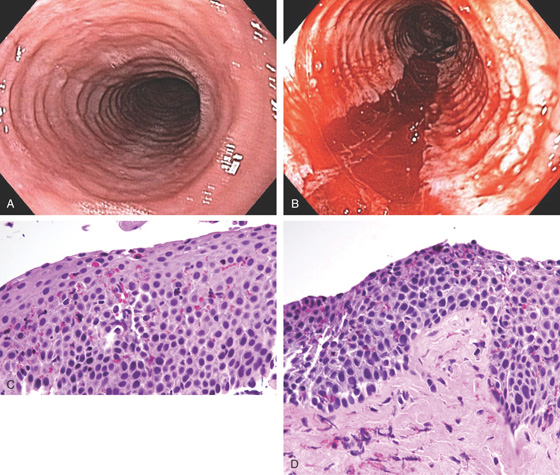

Figure 2.29 CONFOCAL ENDOMICROSCOPY OF NORMAL AND ABNORMAL ESOPHAGEAL LESIONS

A, Normal squamous tissue. B, Intestinal metaplasia. Note the presence of goblet cells. C, High-grade dysplasia. D, Adenocarcinoma (note the disruption of the normal architecture). (D courtesy Don’t Biopsy Study.)

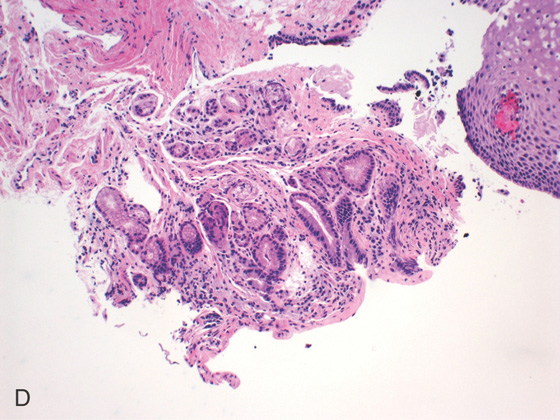

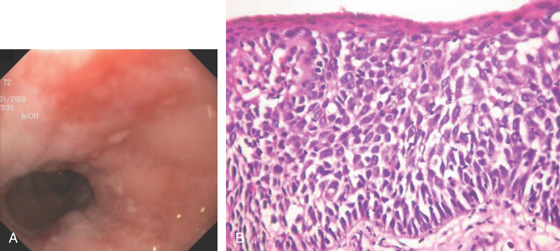

Figure 2.30 BARRETT’S MUCOSA WITH DYSPLASIA

A, Flat hyperemic area in the midesophagus. B, The biopsy specimen shows high-grade dysplasia.

C1, C2, Narrow band imaging shows the abnormal tissue with a distinct demarcation. Note the intraepithelial papillary capillary loops. D, Mucosal resection was performed. (C courtesy Dr. Cristian Gheorghe.)

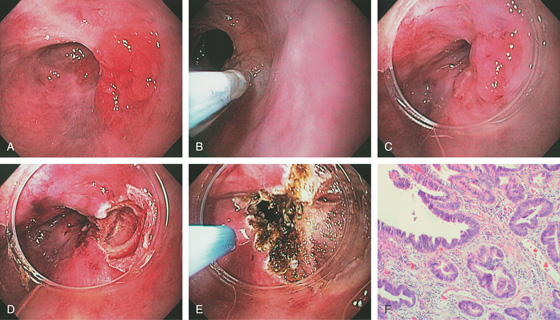

Figure 2.31 BARRETT’S MUCOSA WITH HIGH-GRADE DYSPLASIA: ENDOSCOPIC MUCOSAL RESECTION

A, Nodular well-circumscribed area in the distal esophagus. B, Dilute saline and epinephrine are injected underneath the lesion. C, The cap device is placed on the endoscope and positioned over the lesion for resection. D, After endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), a mucosal defect is produced. E, The argon laser is used to ablate any suspicious surrounding mucosa that was not removed with the resection specimen. F, High-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s mucosa.

Figure 2.32 NODULAR LESION IN BARRETT’S ESOPHAGUS: HIGH-GRADE DYSPLASIA

A, Well-circumscribed nodule in the distal esophagus. B, A cap device is used for resection. C, Mucosal defect after resection.

Figure 2.33 BARRETT’S MUCOSA UNDERGOING RADIOFREQUENCY ABLATION

A, Typical Barrett’s esophagus. This patient had high-grade dysplasia on biopsy. B, After therapy, superficial ulceration is seen. C, Use of the halo device to ablate additional areas of Barrett’s esophagus.

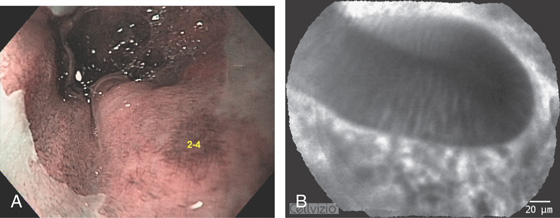

Figure 2.34 BARRETT’S ESOPHAGUS WITH ENDOMICROSCOPY

A, Typical Barrett’s esophagus as seen on narrow band imaging. Numbers represent the area where endomicroscopy was performed. B, Esophageal glands with normal architecture and the presence of goblet cells. No dysplasia is present. (Courtesy F. Alberca, MD, Murcia, Spain.)

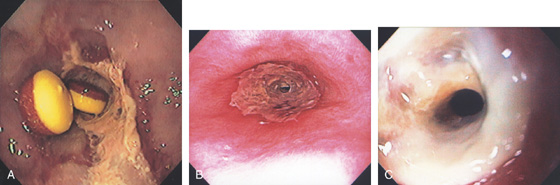

Figure 2.35 GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE-ASSOCIATED STRICTURE

A, Tight stricture of the distal esophagus associated with proximal ulceration. Note the collection of pills proximal to the stricture. B, C, Severe esophagitis with circumferential exudate and an associated tight stricture.

D, The stricture was dilated and endoscopy performed. Note the luminal caliber is improved and there is underlying ulceration of the dilated area. E, After dilation, a large tear is proximal to the stricture.

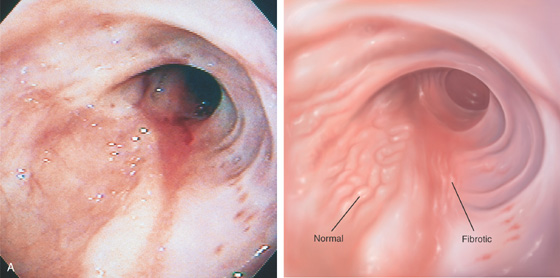

Figure 2.36 HEALED SEVERE GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

A, The esophageal mucosa appears thickened, with loss of vascular pattern from fibrosis. A portion of normal mucosa is still present.

B, Retroflex view in the hiatal hernia shows evidence of prior ulcers, with four well-circumscribed, reepithelialized depressions.

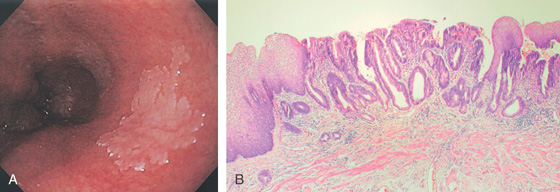

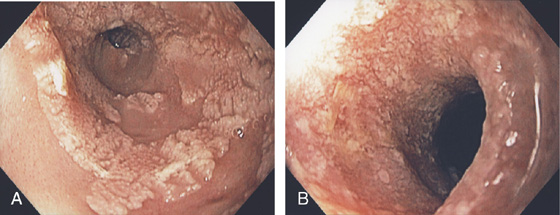

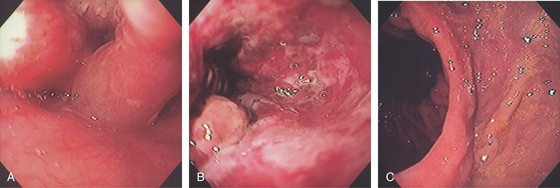

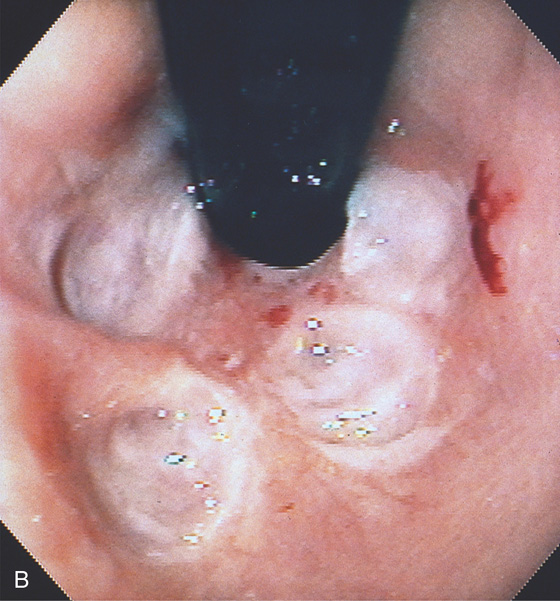

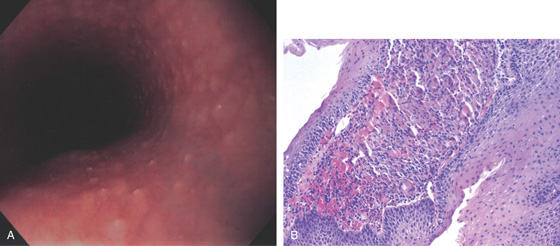

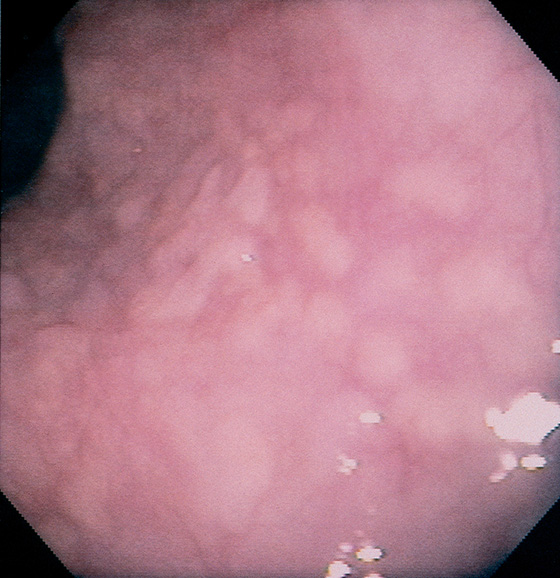

Figure 2.37 MILD CANDIDA ESOPHAGITIS

A, Small white plaques throughout the midesophagus and distal esophagus. B, Multiple white plaques stud the distal esophagus. C, Linear confluent plaques in the midesophagus. The surrounding mucosa is normal.

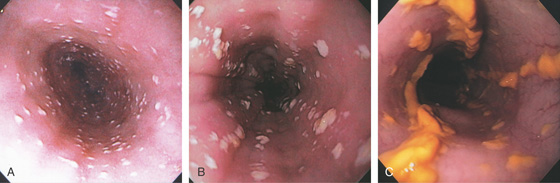

Figure 2.38 CANDIDA ESOPHAGITIS

A, Diffuse irregularity of the wall, with multiple filling defects. These abnormalities result from barium intercalating between the confluent candidal plaques. In most cases, these irregularities do not represent ulceration. B, Typical-appearing raised, confluent yellow plaques. The yellow plaque assumes a linear pattern in some areas, with normal intervening mucosa. C, Severe Candida esophagitis, with confluent circumferential yellow plaque and encroachment on the esophageal lumen. D, If the candidal plaque is vigorously removed, the underlying mucosa appears relatively intact. Denudation of the surface epithelium is seen in a few areas, with associated hemorrhage resulting from the endoscopic trauma. No frank ulceration is present. E, Thick yellow exudate coats the esophagus and results in mild luminal narrowing. F, A portion of the exudate is removed showing inflamed underlying mucosa.

G, Full-thickness squamous epithelium with overlying candidal plaque. The plaque is adherent to the surface epithelium. The plaque is composed of mature squamous epithelial cells, fungal pseudohyphae, and yeast. The Candida does not extend into the deep layers of the epithelium. H, Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain of the candidal plaque demonstrates branching fungal mycelia, including pseudohyphae and true hyphae, characteristic of C. albicans.

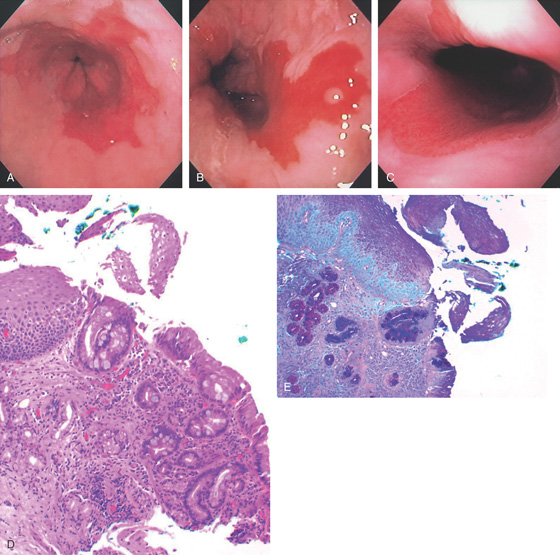

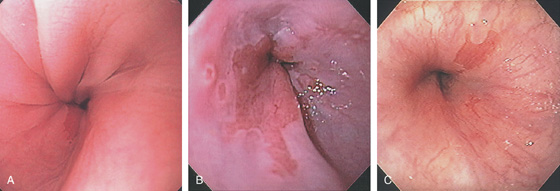

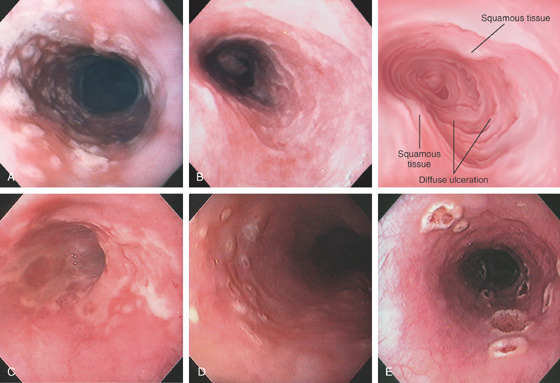

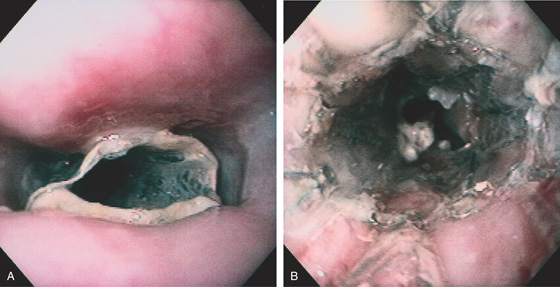

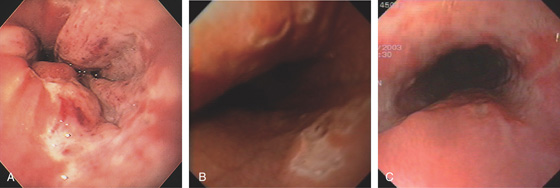

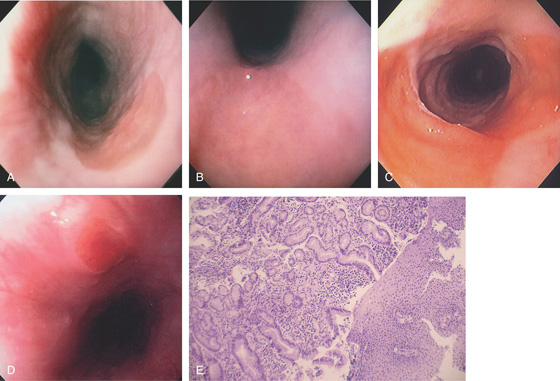

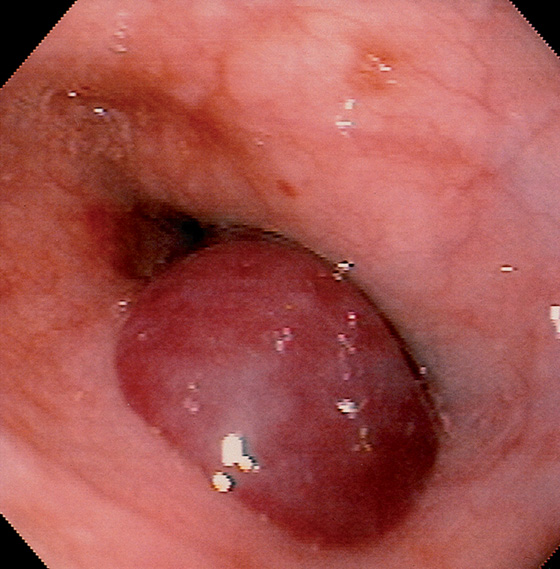

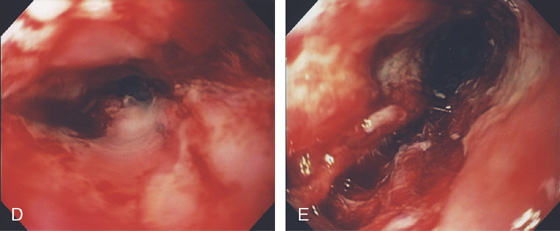

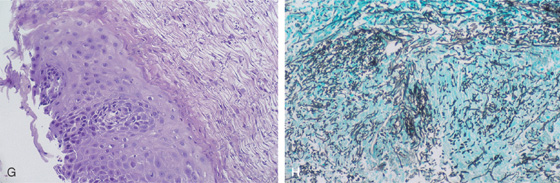

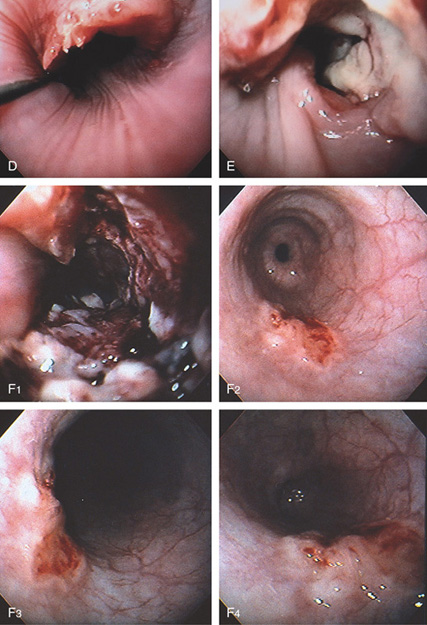

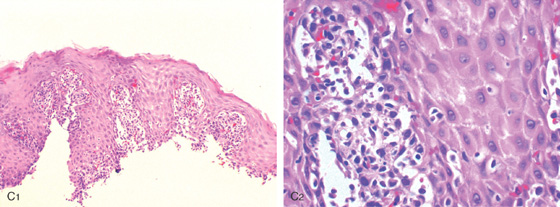

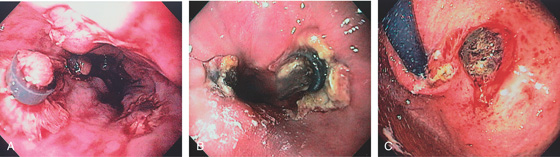

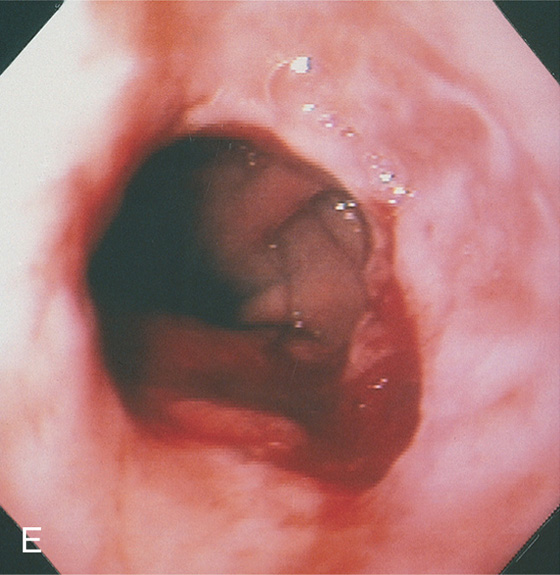

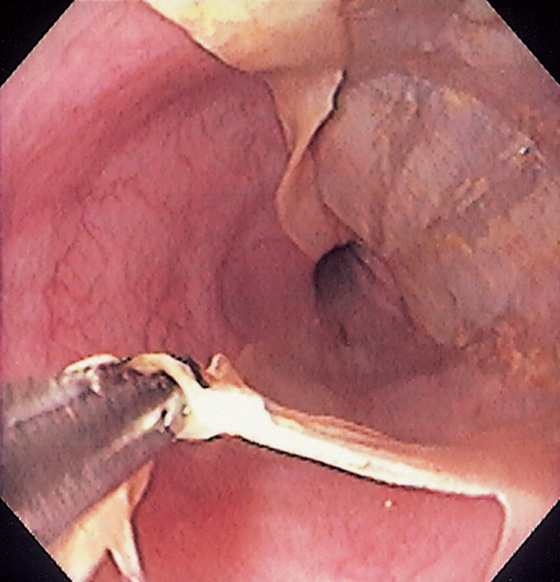

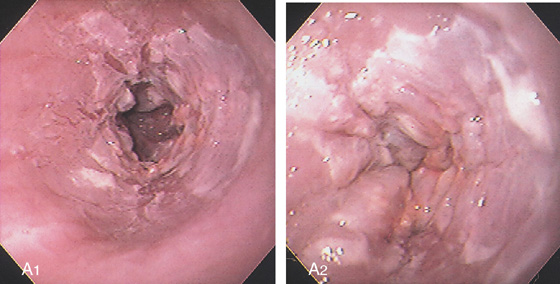

Figure 2.39 HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS ESOPHAGITIS

A, Herpes simplex virus esophagitis manifested by multiple whitish plaques. Diffuse erythema surrounds the plaque, representing shallow ulceration. Islands of normal-appearing esophageal mucosa are still present. B, Diffuse shallow ulceration of the entire esophagus, with two areas of normal-appearing squamous tissue present. C, Confluent exudate in the distal esophagus. D, Vesicular lesions in the midesophagus. E, Volcano-like lesions in the midesophagus.

F1, Large, plaquelike, exudative lesions that become confluent more distally (F2). G, Ulceration with narrowing at the GE junction. The ulcer has thick exudate resembling GE reflux disease.

Figure 2.39 HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS ESOPHAGITIS

H, Herpes simplex virus infection of the esophagus, producing characteristic multinucleated inclusions in squamous epithelial cells. I, Confirmation of herpes simplex virus by in situ DNA hybridization. The intranuclear viral inclusions are stained brown.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Herpes Simplex Virus Esophagitis (Figure 2.39)

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Other infections

Cytomegalovirus

Varicella

Pill-induced esophagitis

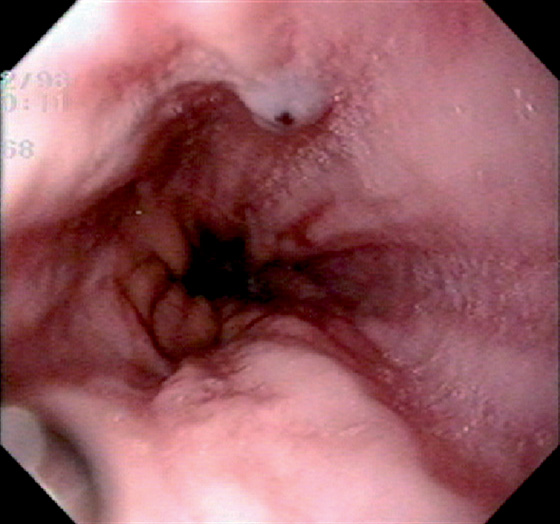

Figure 2.40 VARICELLA ESOPHAGITIS

Diffuse nodularity and pinpoint exudates in the esophagus with fresh bleeding.

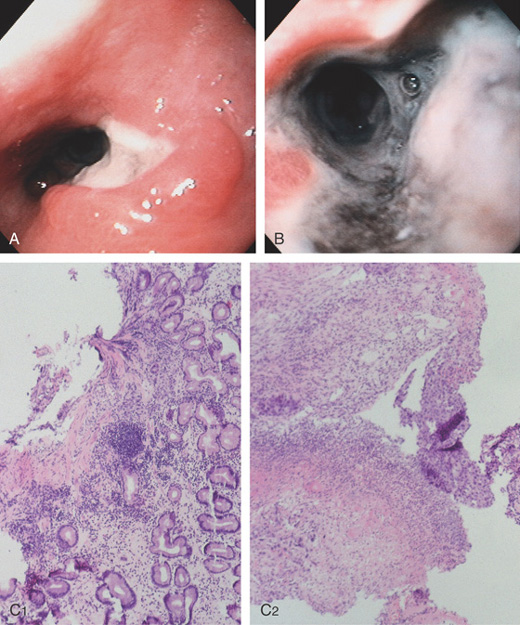

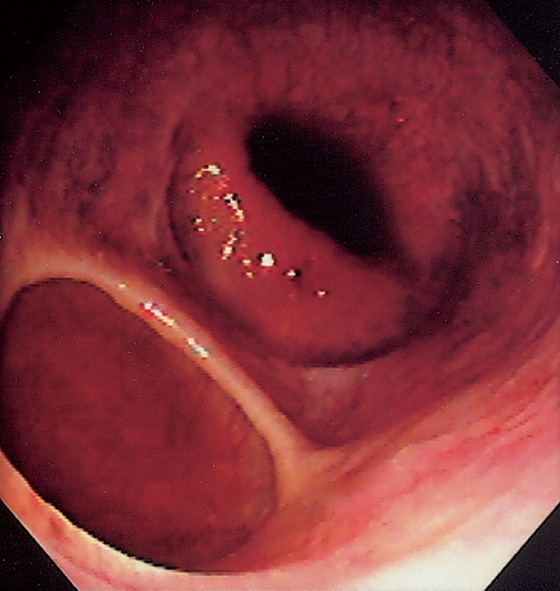

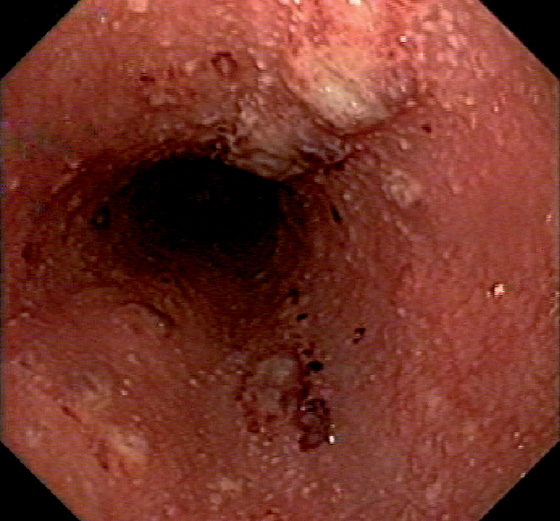

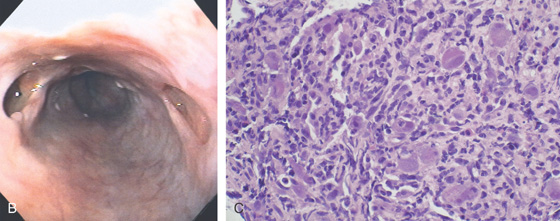

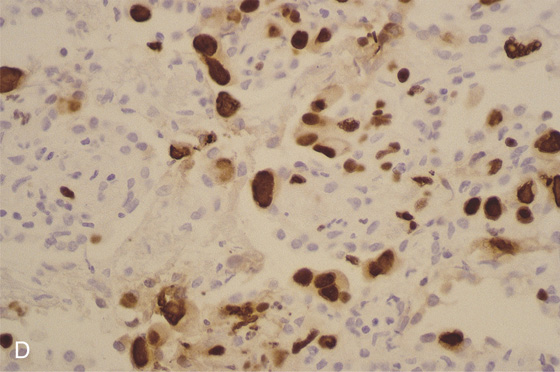

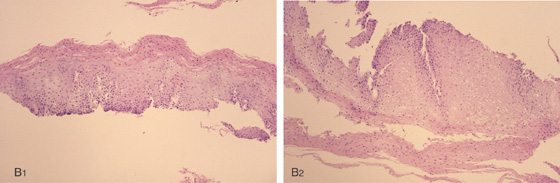

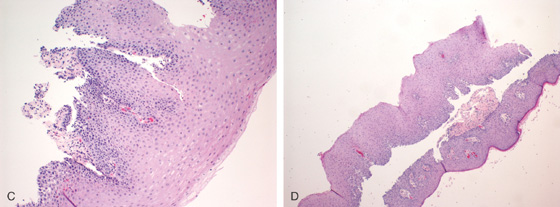

Figure 2.41 CYTOMEGALOVIRUS ESOPHAGITIS

A, Three esophageal ulcerations. Two of the lesions are on opposite walls. There is no extravasation of barium to contiguous structures or to the mediastinum. The surrounding mucosa is normal, giving the ulcerations a well-circumscribed appearance.

B, Multiple large ulcerations. The ulcer on the left represents the deep ulcer on the esophagrams. The distal ulcer is not visible at this level. The ulcers are well-circumscribed, having a “punched-out” appearance. The intervening esophageal mucosa is normal. C, Multiple viral inclusions in endothelial cells and stromal cells in the ulcer base. Cytomegalovirus inclusions typically consist of enlarged cells with characteristic “owl eye” intranuclear inclusions and granular eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions. In the gastrointestinal tract, atypical viral inclusions (some shown here) are often present. Cells with atypical inclusions may appear smudged or can be similar in appearance to ganglion cells.

D, Immunostain confirms the viral cytopathic effect to be cytomegalovirus.

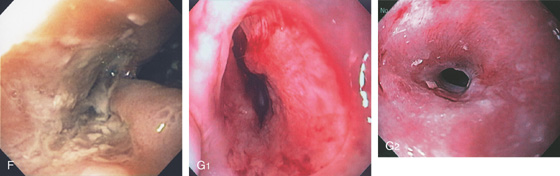

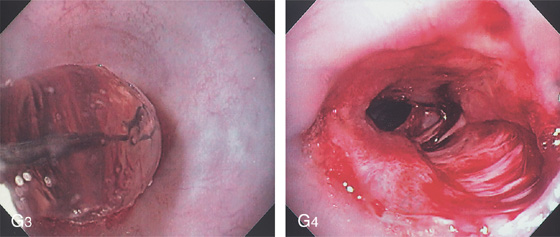

Figure 2.42 CYTOMEGALOVIRUS ESOPHAGITIS

A, Long, linear ulcer. B, Multiple large, well-circumscribed ulcerations in the midesophagus. C, Shallow ulceration in the distal esophagus.

D1, Diffuse exudate in the midesophagus with areas of depression. D2, Markedly thickened distal esophagus. E, Circumferential ulceration involving the distal esophagus.

F, Deep ulceration extending outward from the lumen in the distal esophagus. G1, Midesophageal ulcer with mild luminal narrowing. G2, After therapy, a stricture has resulted.

G3, Balloon dilation performed. G4, The stricture has torn appropriately, now exposing the submucosa. No perforation resulted.

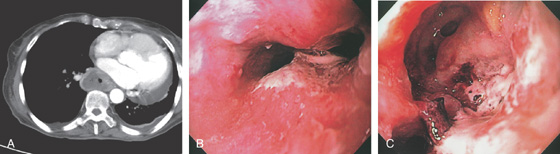

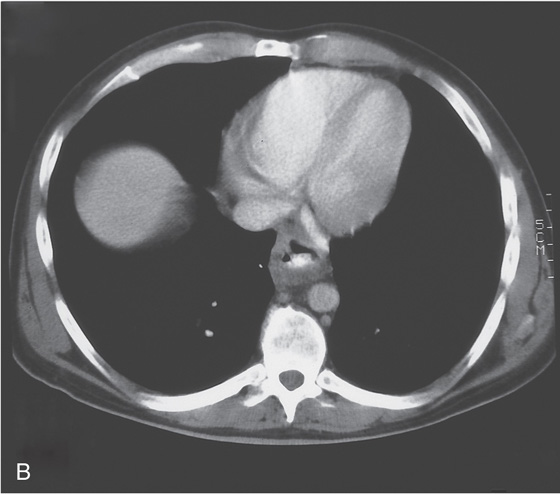

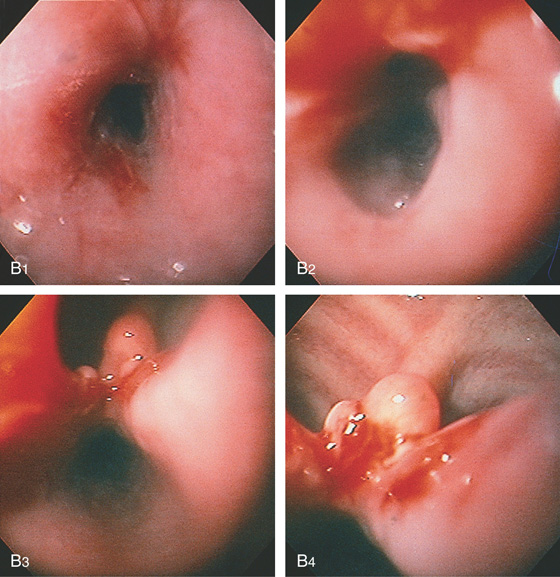

Figure 2.43 CYTOMEGALOVIRUS ESOPHAGITIS WITH STRICTURE

A, Large, irregular ulceration at the gastroesophageal junction. There appears to be a mass effect just proximal to the gastroesophageal junction.

B, The distal esophagus is markedly thickened.

C, Circumferential ulceration in the distal esophagus, extending into the stomach anteriorly and forming a shelf. The gastric tissue is edematous. D, After therapy, the patient reported dysphagia. A circumferential stricture is now present, with persistent active ulceration.

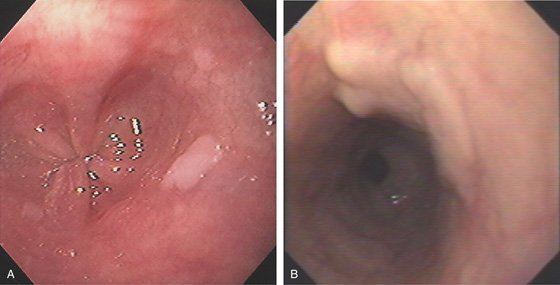

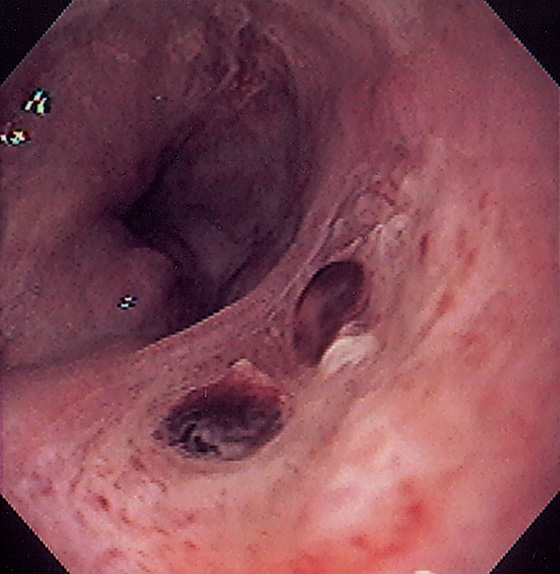

Figure 2.44 HEALED ULCER SCAR

Large scar in the midesophagus representing healing of a large ulcer. Note the characteristic whitish color.

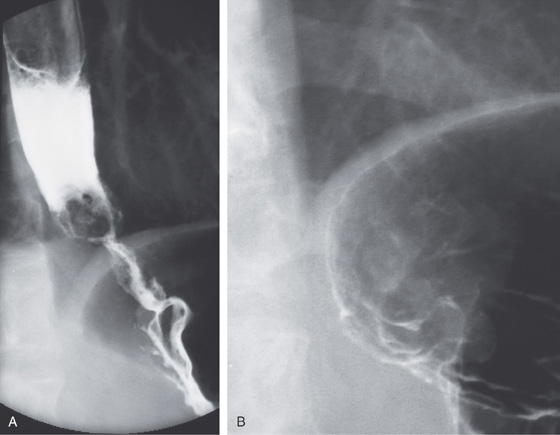

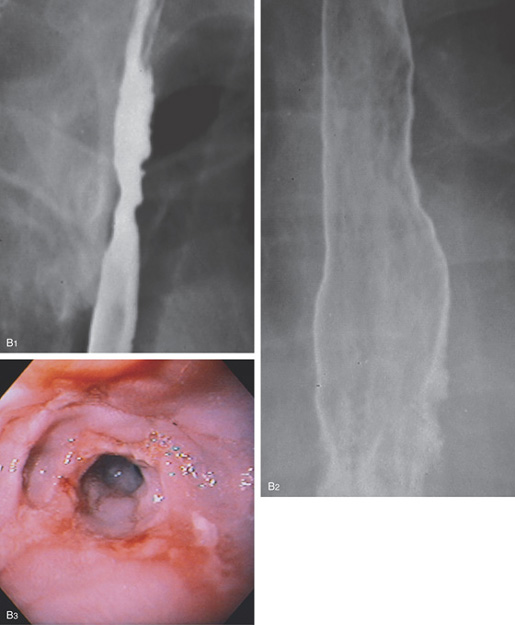

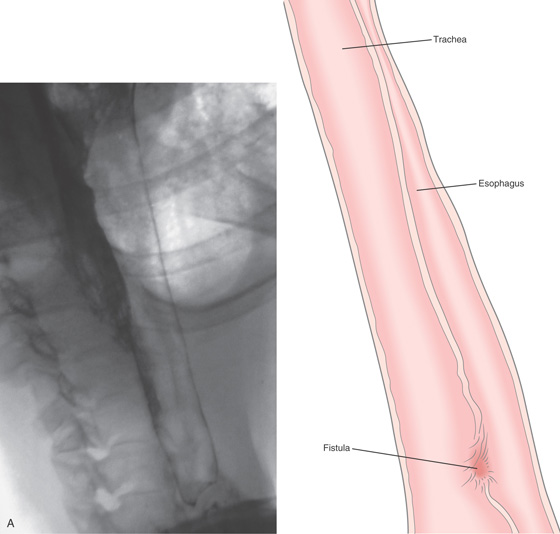

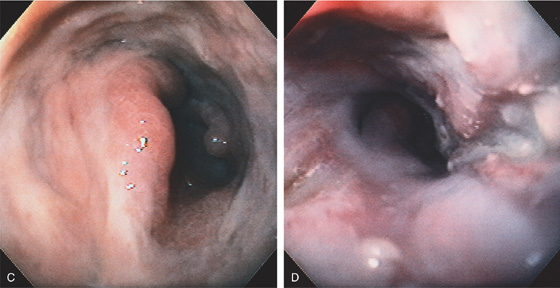

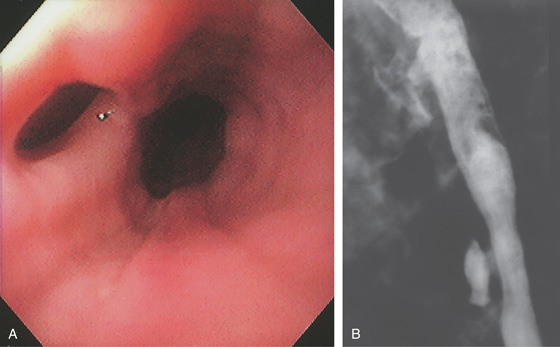

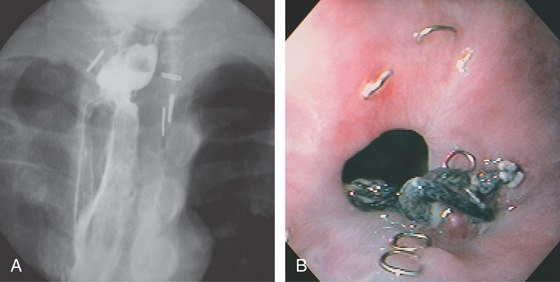

Figure 2.45 TUBERCULOUS ESOPHAGITIS WITH FISTULA

Ulcer in the midesophagus representing a fistula to the mediastinum (A), well shown on barium esophagram (B).

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Tuberculous Esophagitis with Fistula (Figure 2.45)

Infection

Trauma

Neoplasia

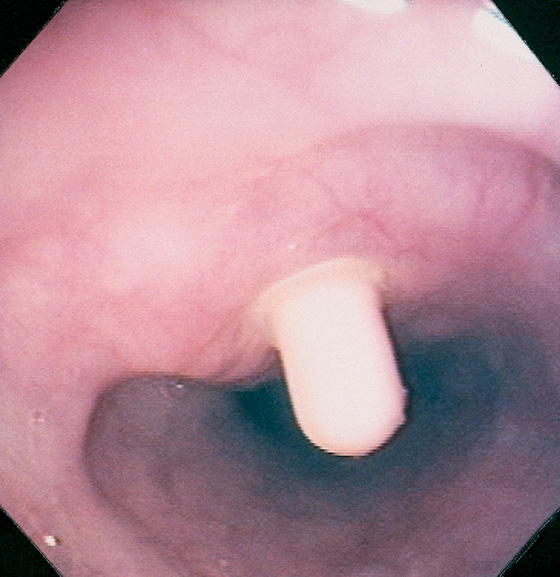

Figure 2.46 ASCARIS LUMBRICOIDES

Large ascarid in the midesophagus. (Courtesy F. Vida, MD, and A. Tomas, MD, Manresa, Spain.)

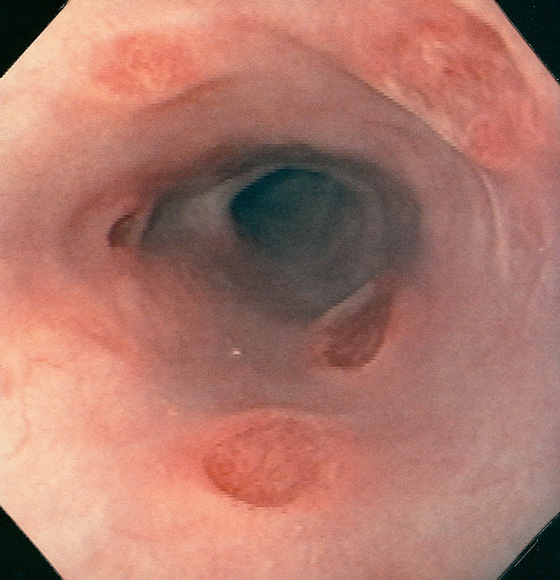

Figure 2.47 EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

A, Multiple mild ringlike lesions of the midesophagus are characteristic.

B, Biopsies show numerous eosinophils in the squamous epithelium.

Figure 2.48 EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

A, Multiple ringlike structures in the distal esophagus above a mild narrowing. B, More proximally, the mucosa has a feline appearance. C1-C3, After biopsy, the blood essentially performs chromoendoscopy, and multiple fissures are also now very evident.

Figure 2.49 DILATION OF EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

A, Typical-appearing rings. B, Long tear after dilation. C, Biopsy shows marked eosinophilia. D, Dense fibrosis is also present in the submucosa.

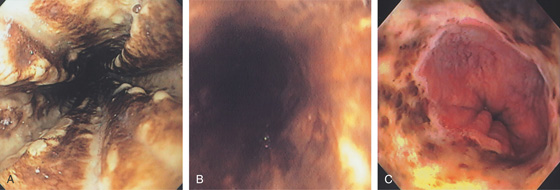

Figure 2.50 ACUTE NECROTIZING ESOPHAGITIS

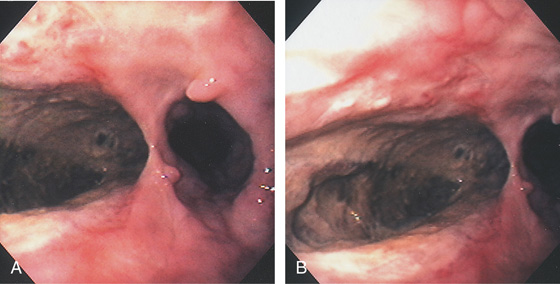

Diffuse black exudates coat the esophagus (A, B). C, Note the abnormalities stop at the GE junction.

Figure 2.51 PEMPHIGUS

A, Submucosal hemorrhage in the midesophagus. B, The biopsy forceps are used to grasp the overlying mucosa showing that it can be “peeled away.”

C, D, More extensive esophageal involvement with sloughing of a large portion of the mucosa. The thin film of detached mucosa is visible.

Figure 2.52 PARANEOPLASTIC PEMPHIGUS

Diffuse edema and subepithelial hemorrhage.

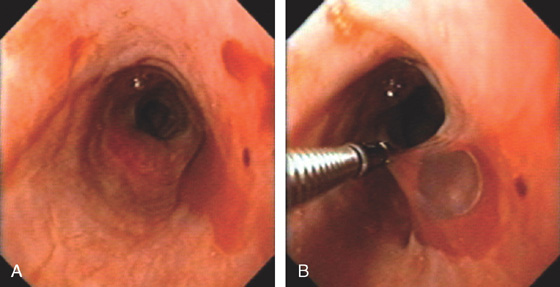

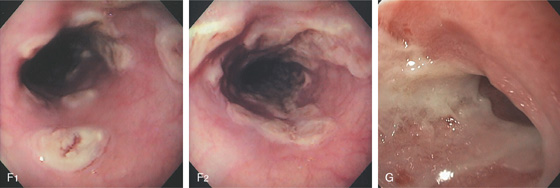

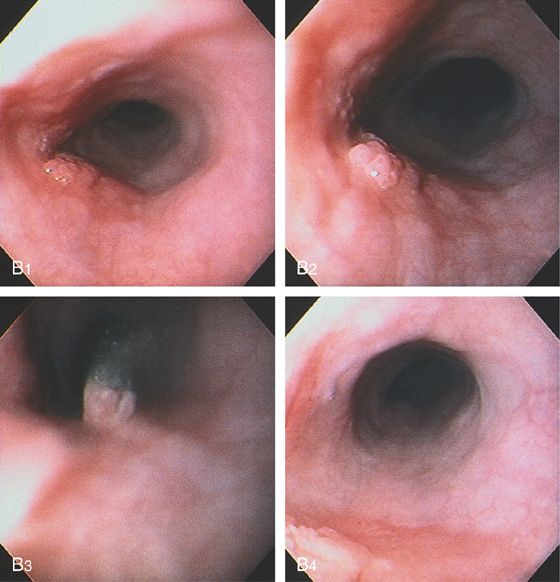

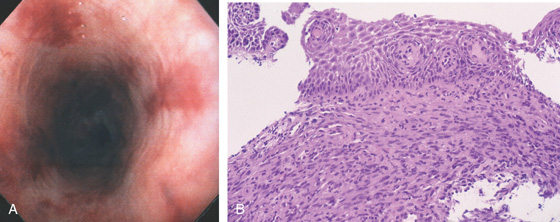

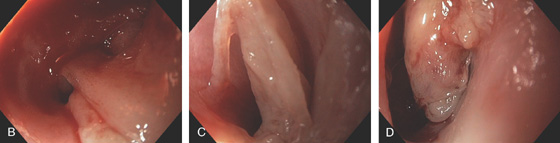

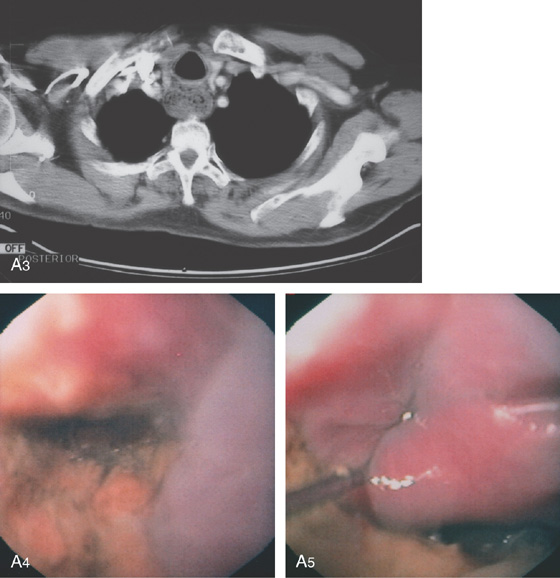

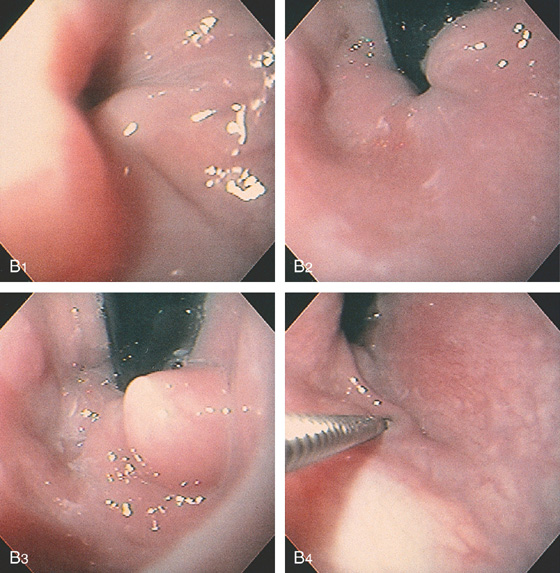

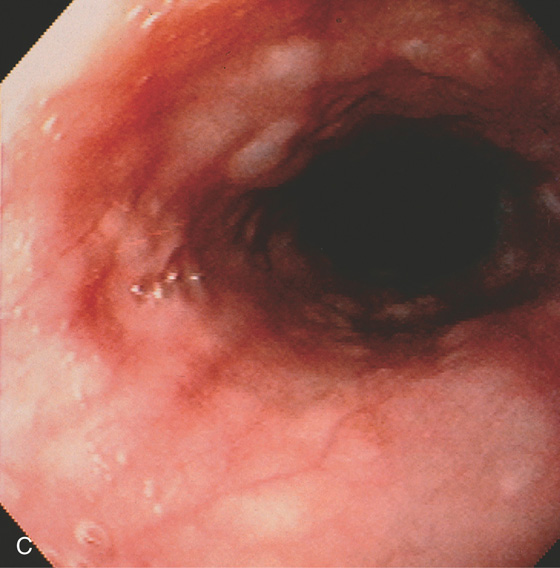

Figure 2.53 EARLY SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

A, Focal area of nodularity. Air bubbles can also be seen on the barium-coated esophagus.

B1, B2, Verrucous-appearing lesion in the center of a well-demarcated area of erythema. B3, After washing of the lesion, it is found not to be fixed to the wall. B4, A distal border of erythema is present. Biopsy of the erythematous mucosa demonstrated carcinoma.

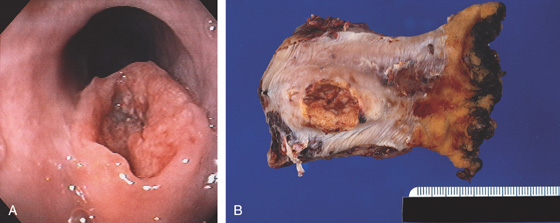

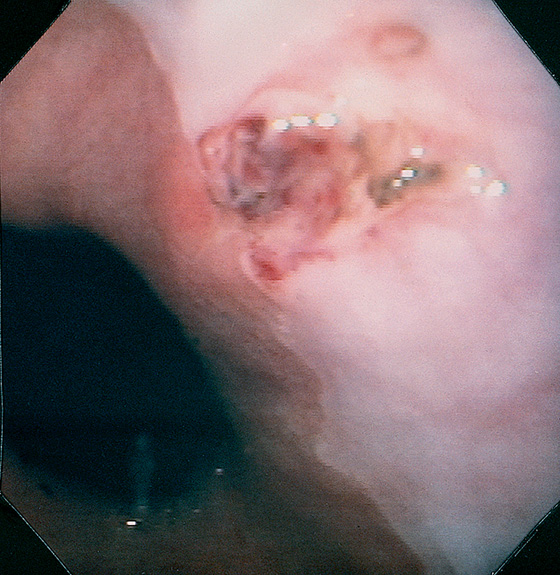

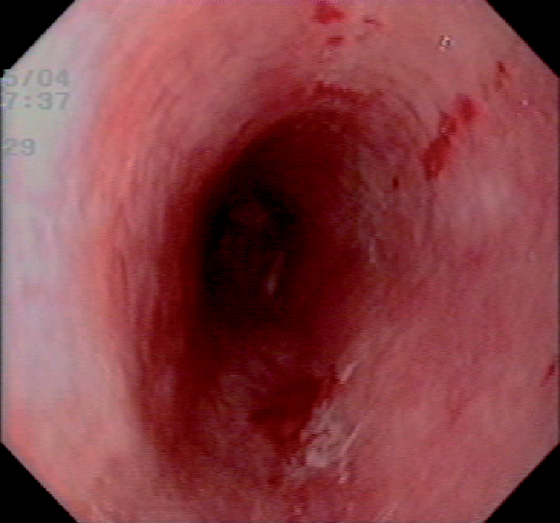

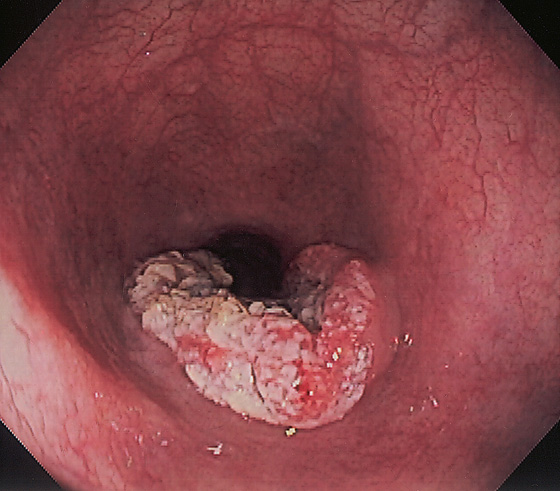

Figure 2.54 SQUAMOUS CELL CANCER OF THE ESOPHAGUS WITH RECENT BLEEDING

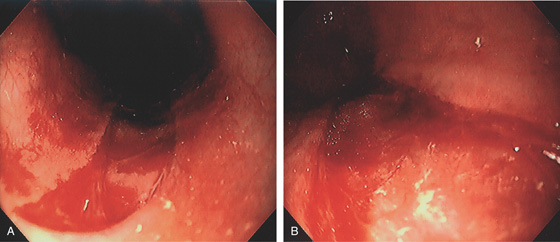

Raised ulcerative lesion of the midesophagus with overlying blood clot indicating recent bleeding (A, B).

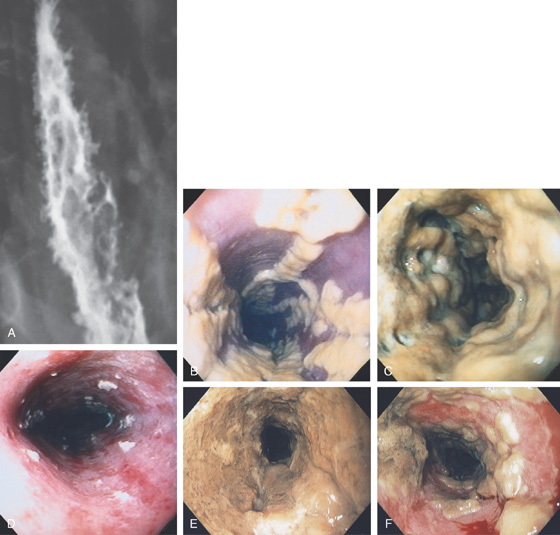

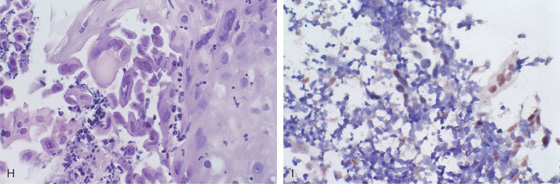

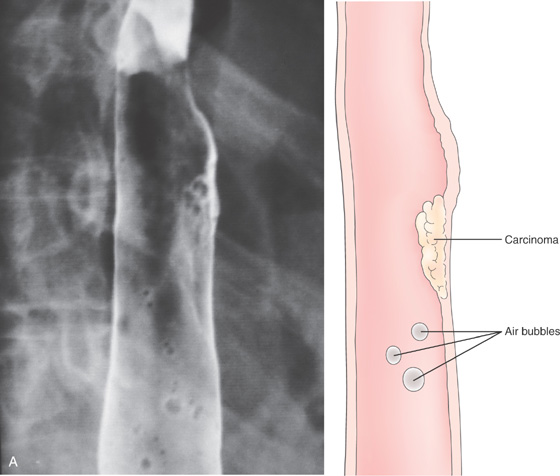

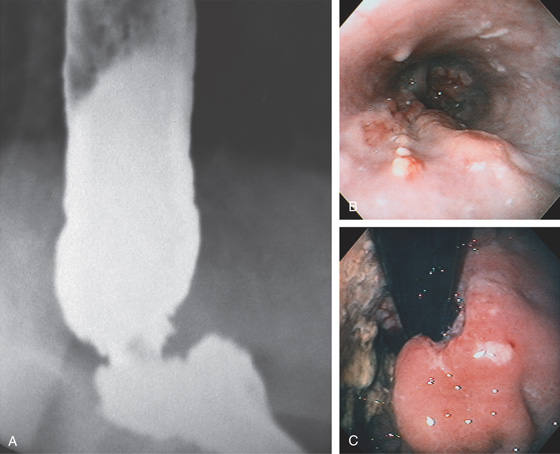

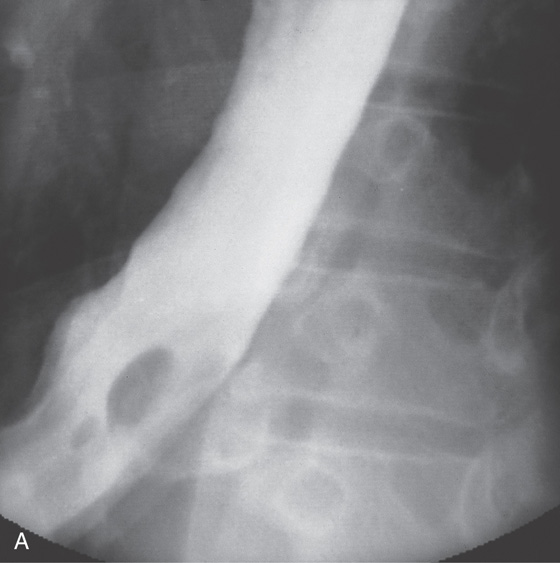

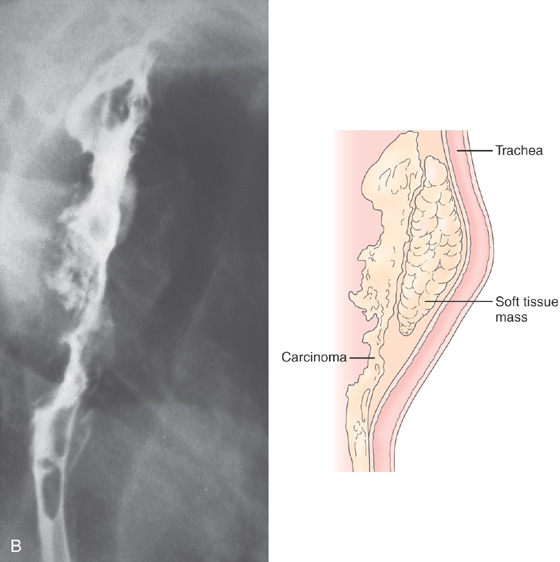

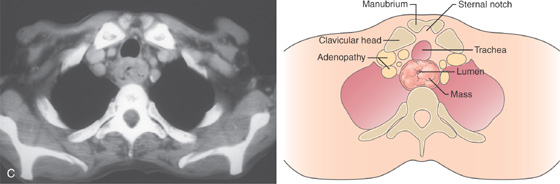

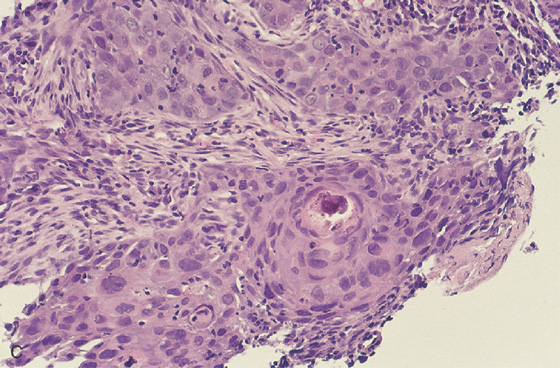

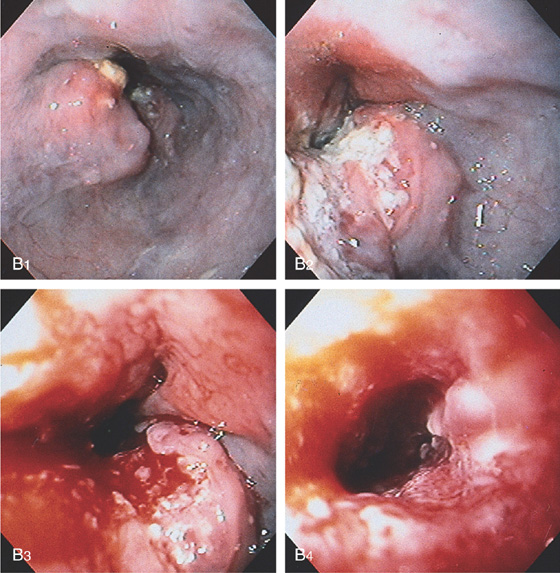

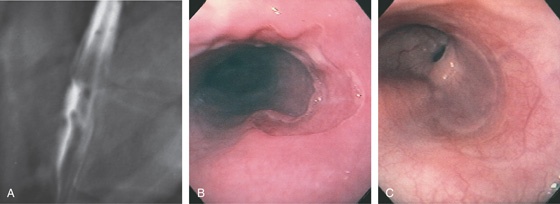

Figure 2.55 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

A, Anteroposterior view shows a long segmental lesion, with nodular mucosa and luminal narrowing.

Figure 2.55 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

B, A soft-tissue mass anteriorly causes a mass effect, with posterior effacement of the trachea.

C, Mass lesion of the cervical esophagus at the level of the manubrium. The esophageal lumen is severely compromised. Adenopathy is present.

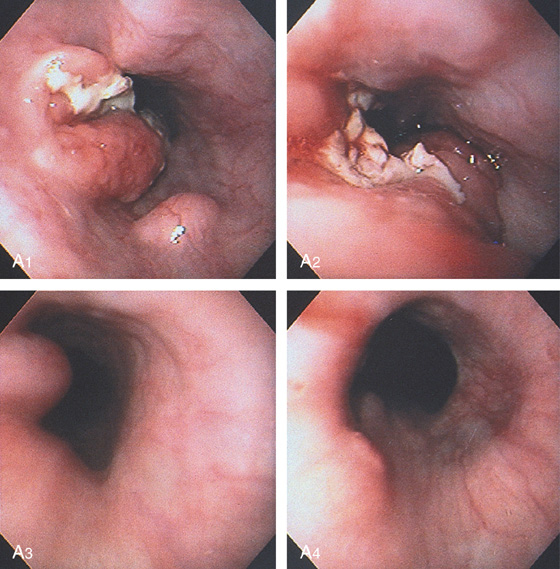

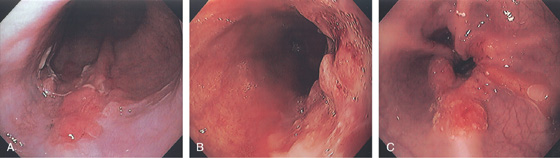

Figure 2.55 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

D, Proximal lip of the tumor. A guidewire is present. E, Hemicircumferential ulceration. F1, Appearance of the lesion after dilation. F2-F4. An ulcer with irregular margins in the distal esophagus was also a squamous cell carcinoma. The lesion was found after dilating the stricture. This could be a second primary carcinoma, which is unusual, or a metastatic lesion.

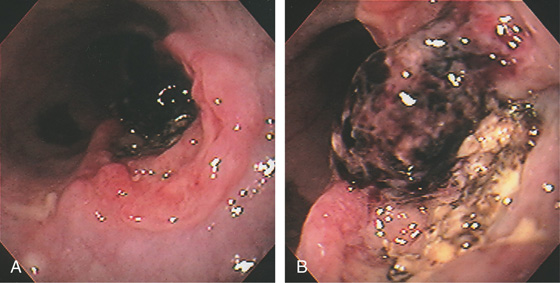

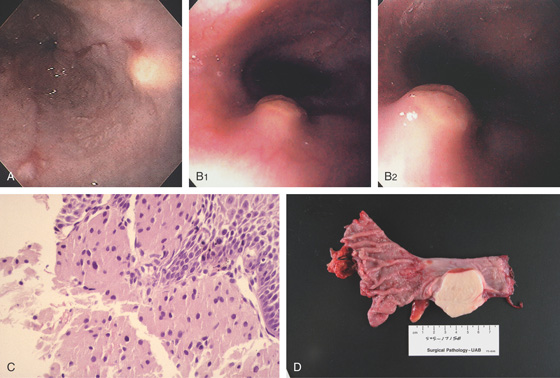

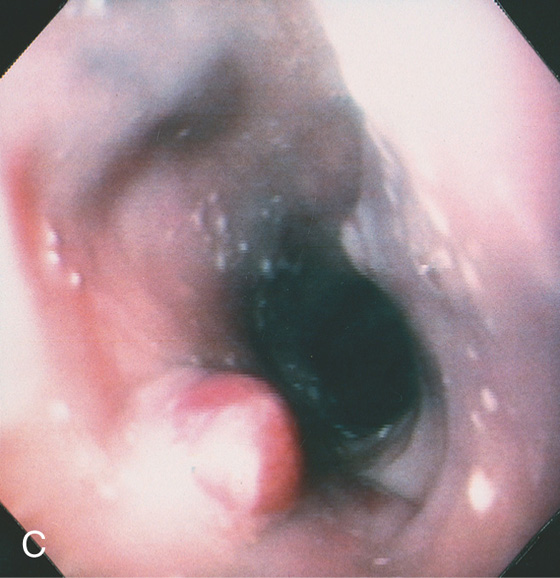

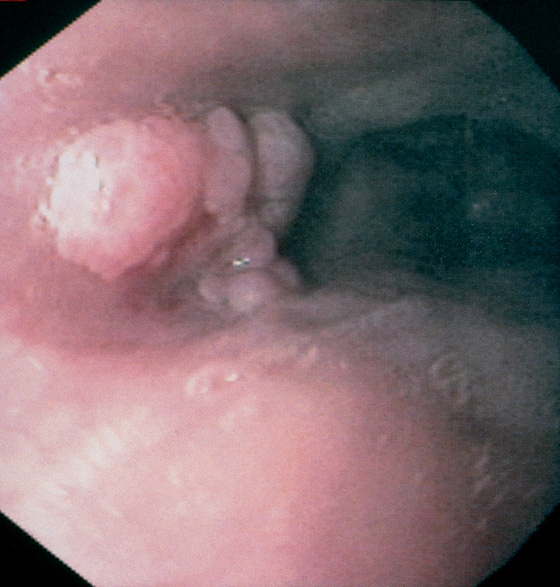

Figure 2.56 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

A, The cancer has a volcano appearance, with a central area of necrosis surrounded by normal-appearing squamous mucosa. B, Surgical specimen demonstrates a mass lesion protruding from normal-appearing squamous mucosa.

C, Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

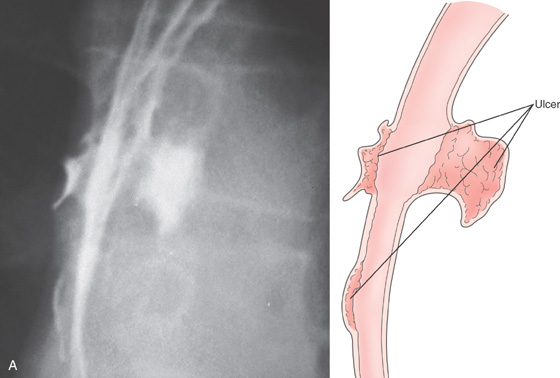

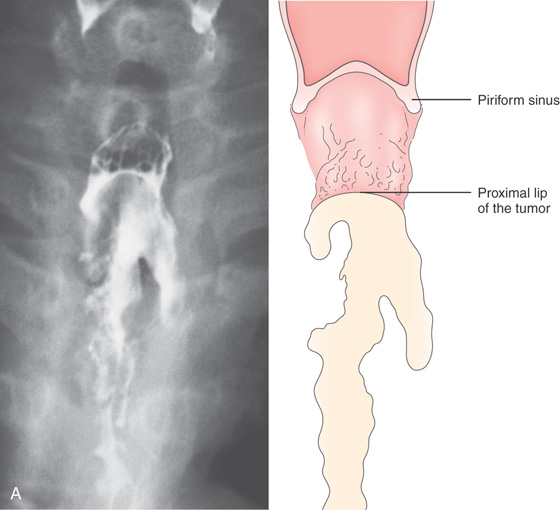

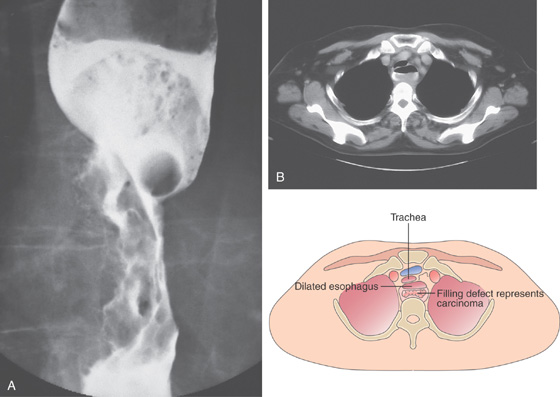

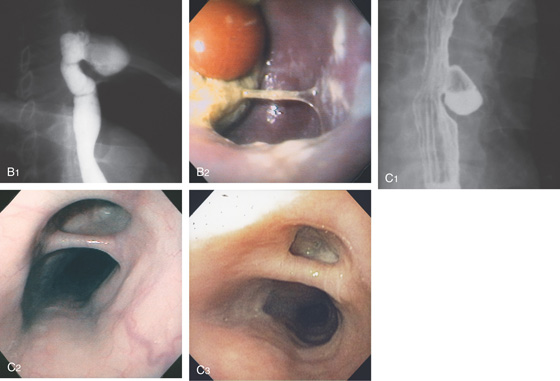

Figure 2.57 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

A, Irregular, masslike lesion producing high-grade partial obstruction of the esophageal lumen. The proximal esophagus is dilated, and a round nodular intraluminal mass is seen in the barium column, representing proximal luminal tumor extension. A round structure is present at the proximal portion of the carcinoma, suggesting a pill. Note the difference in caliber between the proximal and distal esophagus. B, The esophagus is dilated with residual barium. A filling defect is also present in the barium column. The posterior and left posterolateral walls of the trachea are deformed by the lesion. Adenopathy is present anteriorly.

C, Luminal narrowing of the esophagus outlined by the barium column, with surrounding mass lesion. D, Proximal portion of the tumor is hemicircumferential and has a fleshy appearance. A pill is embedded in the tumor.

E, The resection specimen demonstrates the bulkiness of the tumor and luminal impingement.

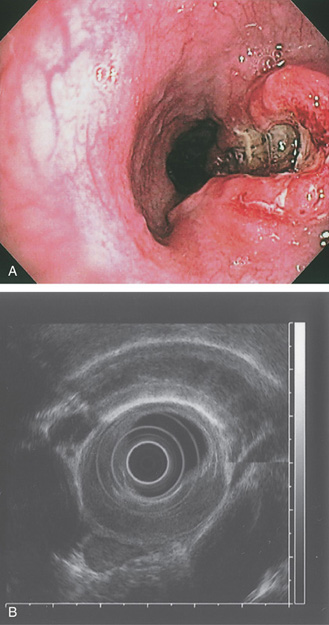

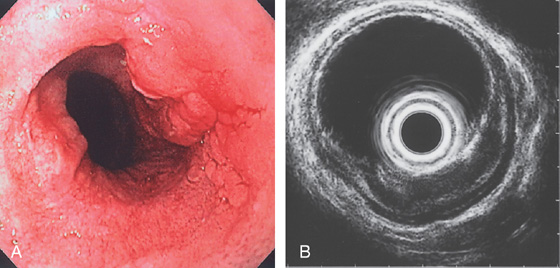

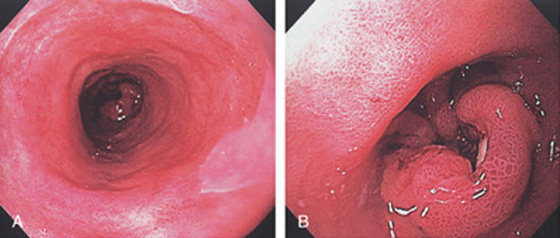

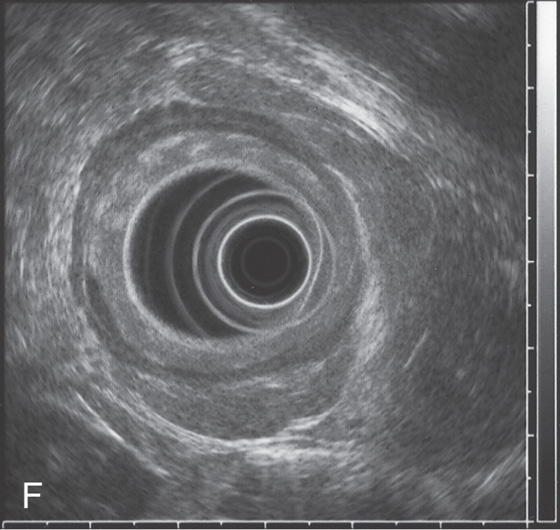

Figure 2.58 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

A, Ulcerated lesion of the midesophagus with heaped-up margins. B, Endoscopic ultrasonography confirms the tumor extent and adjacent lymph nodes.

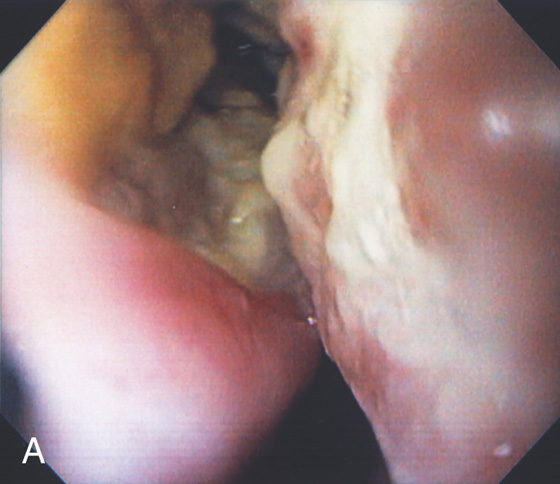

Figure 2.59 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA WITH TRACHEAL–ESOPHAGEAL FISTULA

An irregular nodular stricture with proximal shelving and a fistulous communication to the right lower lobe bronchus. Other areas of apparent fistula formation represent sinus tracts in the tumor mass.

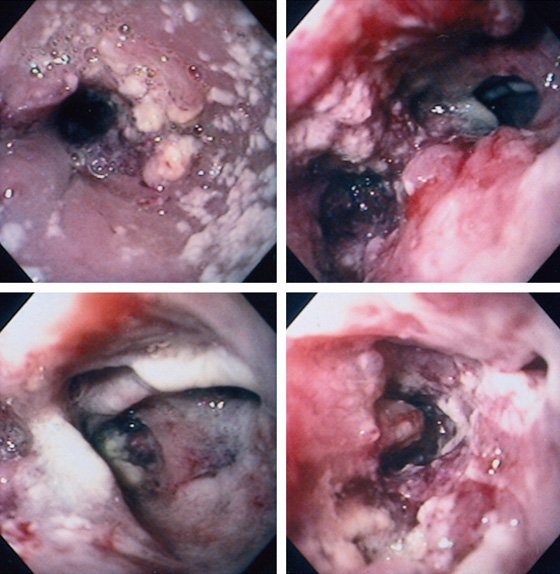

Figure 2.60 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA WITH TRACHEAL–ESOPHAGEAL FISTULA

Dilated esophagus with multiple white plaques, characteristic of Candida esophagitis. Candida esophagitis commonly occurs in areas of stasis resulting from obstruction. The proximal portion of the tumor is evident by the hemicircumferential rim of nodularity. The distal lumen is narrowed (top left). Two lumina are seen distal to the proximal portion of the tumor (top right). On the left, the esophageal lumen with circumferential carcinoma is shown; the lumen on the right is the large fistula. The fistula has an ulcerated appearance (bottom left). The circumferential ulcerated tumor is present distally in the esophagus (bottom right).

Figure 2.61 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

A1, A2, A raised, masslike lesion with central ulceration. A submucosal nodule is adjacent to the tumor. A3, A4, Distal to the tumor are several submucosal nodules.

B, A mass lesion in the gastric cardia. A well-circumscribed pooling of barium can be seen in the middle of the lesion.

C, Retroflex view of the gastric fundus reveals a large mass lesion with central ulceration. The lesion has the appearance of an extrinsic lesion that has ulcerated in its central portion. Biopsy of the lesion demonstrated squamous cell carcinoma.

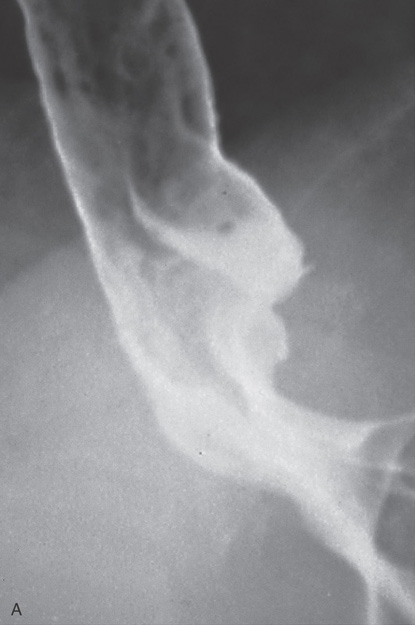

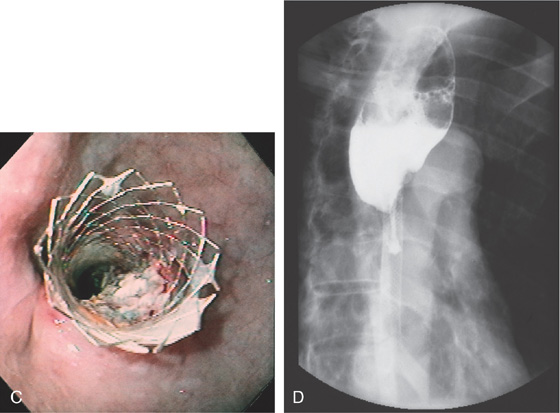

Figure 2.62 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

A, Long, irregular stricture characteristic of a neoplasm. The proximal portion of the tumor has shelving and is dilated.

B1, The shelflike lesion is evident. B2, The center of the tumor has a necrotic appearance. B3, B4, The midportion of the tumor becomes circumferential and friable, with significant luminal narrowing.

C, Gianturco metal stent placed into the esophageal cancer, resulting in luminal patency. Tumor is growing into the mesh stent. D, The stent is in a good position through the tumor mass. Barium is outlining the wire mesh of the stent.

Figure 2.63 POLYURETHANE-COATED ESOPHAGEAL STENT

A, Proximal portion of the stent. B, The polyurethane coating of the metal stent avoids ingrowth of tumor. The metal flanges are beneath the polyurethane.

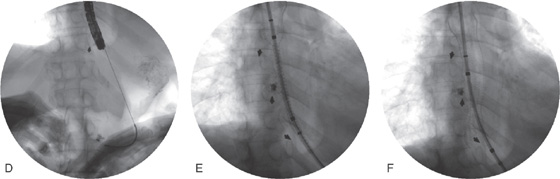

Figure 2.64 STENTING OF SQUAMOUS CELL CANCER

A, Large mediastinal lesion with luminal compromise. B, Luminal compromise of the midesophagus with mediastinal extension of the tumor. C, Ulceration extending to the mediastinum.

D, A wire has been placed through the tumor into the stomach and the most proximal margin of the tumor is marked with an arrow. E, The stent is passed fluoroscopically to the GE junction and deployed. Note the proximal opening of the stent and the distal markings with the arrow. F, Stent has been fully deployed.

G, The endoscope is passed through the stent to the level of the fistula noting adequate deployment. H, Appearance of the stent after deployment. I, Proximal extent of the prosthesis.

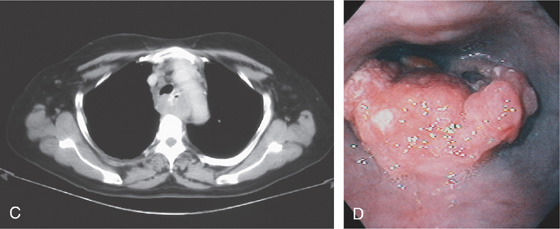

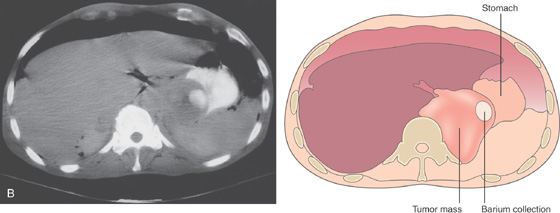

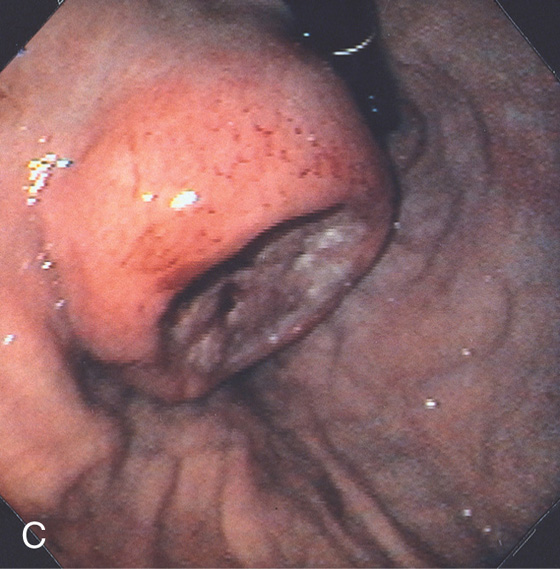

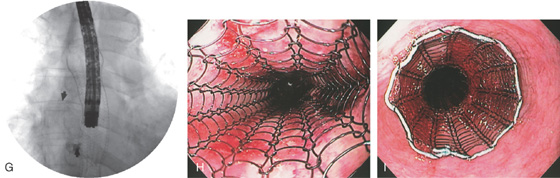

Figure 2.65 ADENOCARCINOMA

A, Irregular stricture at the gastroesophageal junction. In the proximal portion of the stricture, a mass lesion is present in the barium column. The proximal esophagus is dilated. The lesion can be seen extending into the gastric fundus. B, An irregular, masslike lesion is outlined by the residual barium.

C, The circumferential masslike lesion is adjacent to the liver and impinging on the gastric fundus. The lumen is significantly narrowed. D, The proximal tumor appears as a round, nodular, masslike lesion. Part of the tumor appears to have normal overlying squamous mucosa. E, Retroflex view of the proximal stomach demonstrates hemicircumferential ulceration with a mass lesion, typical of adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction.

Figure 2.65 ADENOCARCINOMA

F, The overlying squamous epithelium is compressed by poorly differentiated tumor occupying the submucosa. G, The mucicarmine stain is useful in identifying mucin-producing adenocarcinoma.

Figure 2.66 ADENOCARCINOMA WITH PROXIMAL SUBMUCOSAL EXTENSION

A, Dilated esophagus with a short, ulcerated stricture at the gastroesophageal junction. The distal esophageal mucosa is irregular. The proximal stomach appears to be involved, with an ulcerated masslike lesion. B, Nodularity of the distal esophagus with overlying areas of necrosis, resulting from proximal submucosal extension of adenocarcinoma at the gastroesophageal junction. Candidal plaques are also present as a result of the distal obstruction, with secondary stasis. C, Retroflex view of the cardia shows a hemicircumferential ulcerated mass.

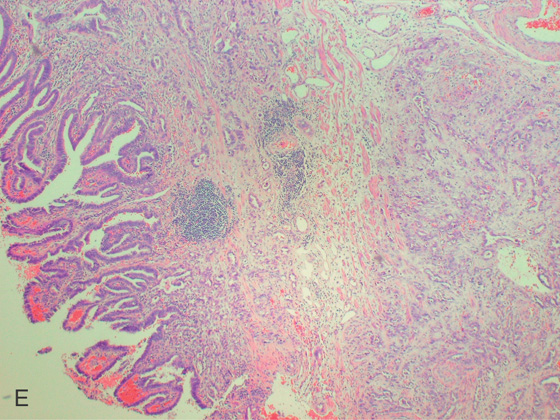

Figure 2.67 BARRETT’S-ASSOCIATED ADENOCARCINOMA

A, Focal area of nodularity at the proximal margin of a hiatal hernia at the site of Barrett’s mucosa. B, Focal area of nodularity at the proximal extent of a long segment of Barrett’s esophagus. C, Circumferential narrowing of the distal esophagus. Note the tumor involves the Barrett’s mucosa.

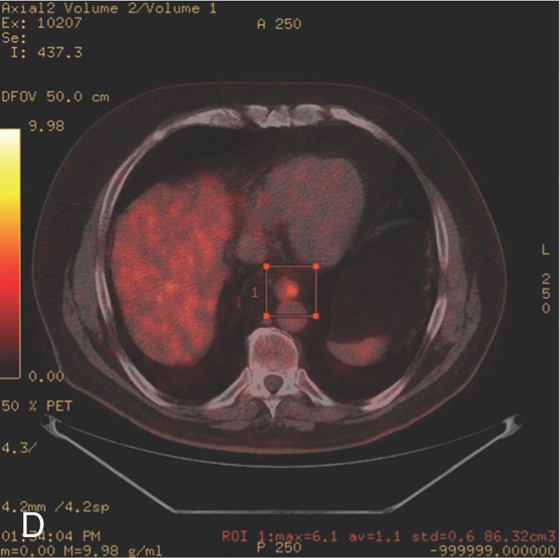

D, PET scan shows focal positivity in the distal esophagus.

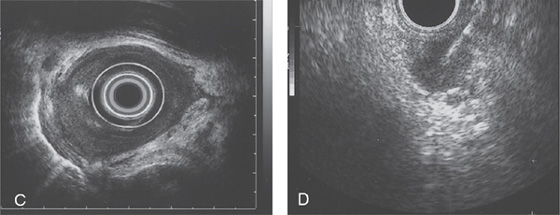

Figure 2.68 BARRETT’S ASSOCIATED ADENOCARCINOMA

A, Proximal extent of the long-segment Barrett’s-associated adenocarcinoma. Note the lesion in the distance. B, Raised ulcerated lesion.

C, Endoscopic ultrasonography shows the mass lesion to be invading the adventitia. D, Fine needle aspiration of a celiac lymph node confirms metastatic disease.

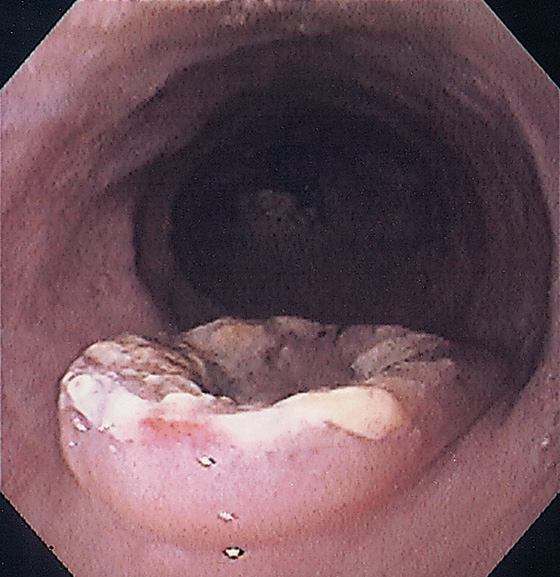

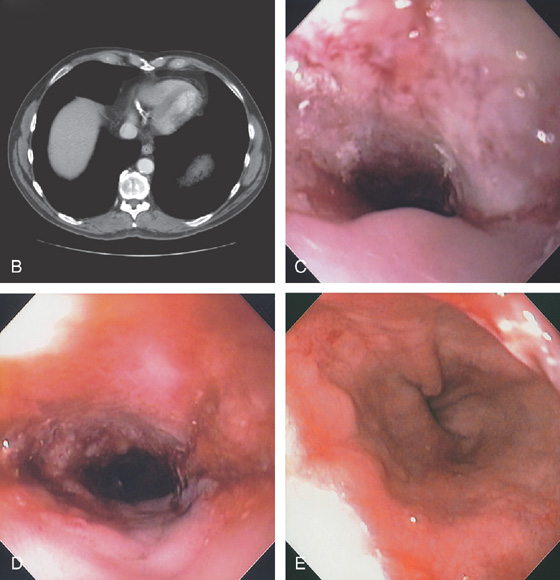

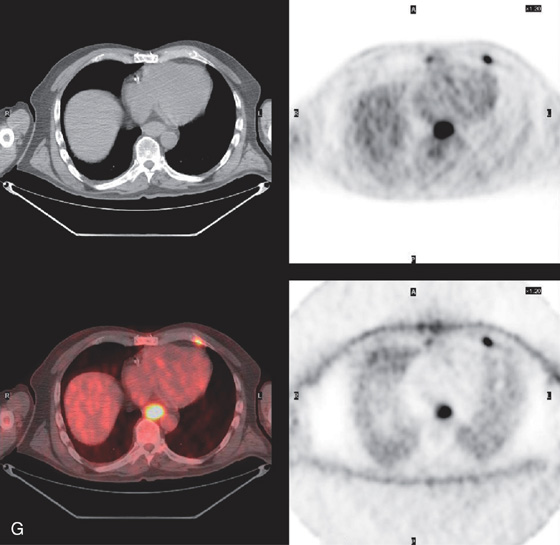

Figure 2.69 BARRETT’S-ASSOCIATED ADENOCARCINOMA

A, Stricture of the distal esophagus.

B, Circumferential thickening of the distal esophagus. C, Hemicircumferential ulceration at the point of luminal narrowing in the distal esophagus. D, The area of neoplastic obstruction is now open after dilation. E, Note the distal extent of the tumor and the Barrett’s mucosa in the distance.

F, Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) shows invasion of muscularis and adventitia (T3 stage).

G, PET scan demonstrates the tumor.

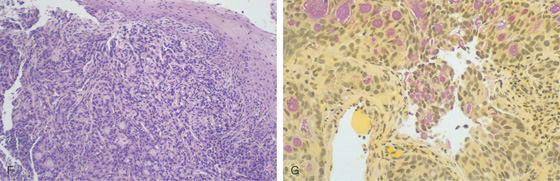

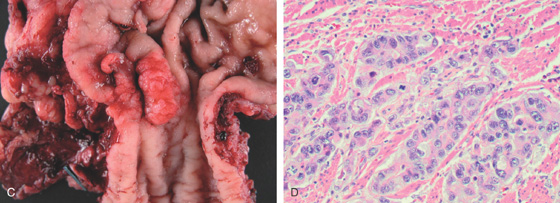

Figure 2.70 BARRETT’S-ASSOCIATED ADENOCARCINOMA

A, Nodular mass lesion at the GE junction in the setting of Barrett’s esophagus. B, Endoscopic ultrasonography confirms a T3 tumor that involves the muscularis.

C, Surgical resection specimen. D, Adenocarcinoma on hematoxylin and eosin staining.

E, Note the tumor invasion of the submucosa.

Figure 2.71 NON-HODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA

Well-circumscribed ulcerated “donut” lesion in the proximal esophagus.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (Figure 2.71)

Squamous cell carcinoma

Metastatic tumors

Melanoma

Lung carcinoma

Breast carcinoma

Lymphoma

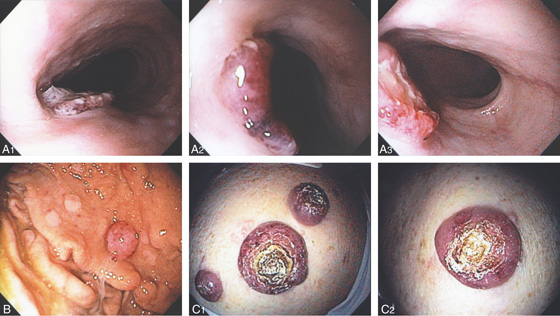

Figure 2.72 BURKITT’S LYMPHOMA

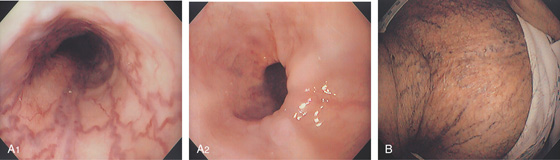

A1, A2, Multiple well-circumscribed, raised, ulcerated dark lesions of the esophagus. There is central ulceration (A3). Note the resemblance to the gastric lesion (B) and to the nodular skin lesions (C1, C2).

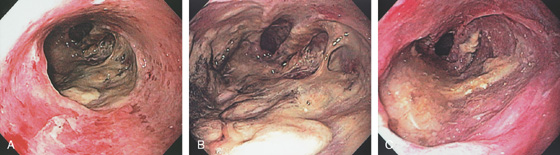

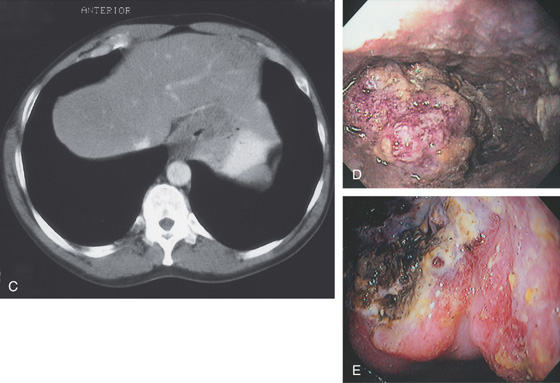

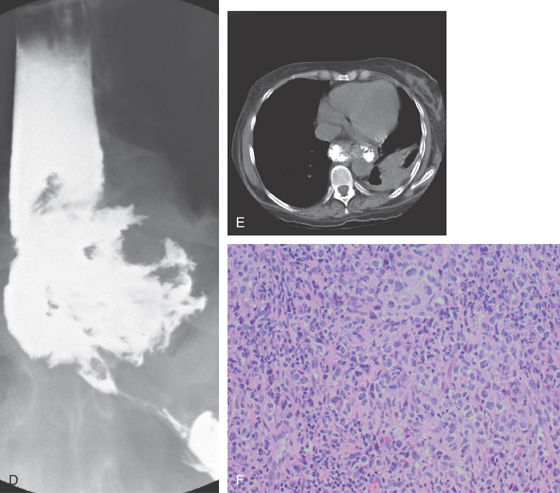

Figure 2.73 POST-TRANSPLANT LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDER

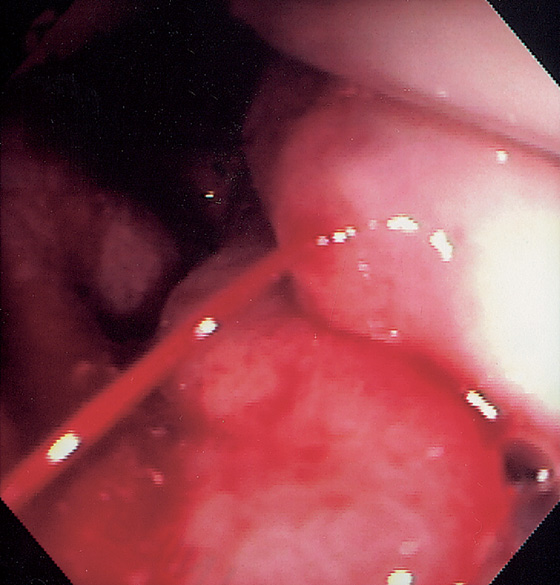

A, Distal esophagitis with a large necrotic ulcerative lesion. B, Close-up shows the diffuse exudate. C, With washing, a large ulcerative lesion is identified. Note the luminal narrowing distally.

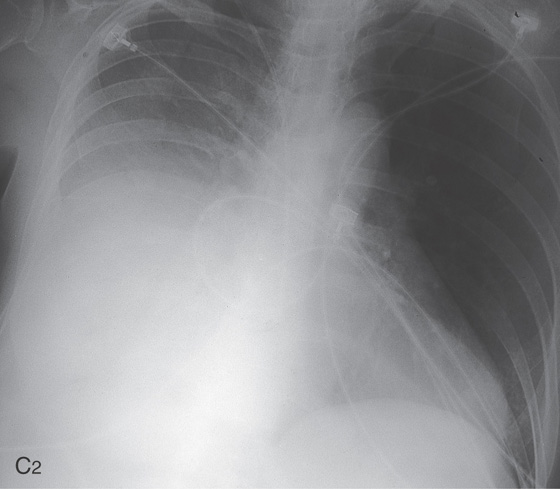

D, Upper GI shows the large ulcer proximal to the GE junction with distal narrowing. E, CT shows the extent of the GE junction lesion. F, Hematoxylin and eosin stain shows infiltration with lymphocytes.

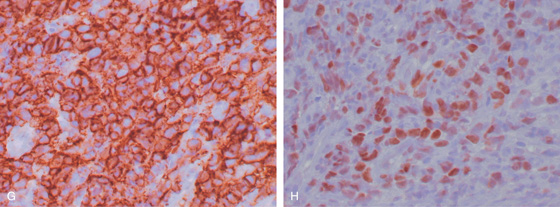

Figure 2.73 POST-TRANSPLANT LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDER

G, CD20 immunostain is positive, indicating a population of B cells. H, Staining for Epstein-Barr virus is positive, typical for a lymphoproliferative disorder after transplant.

Figure 2.74 LEUKEMIA

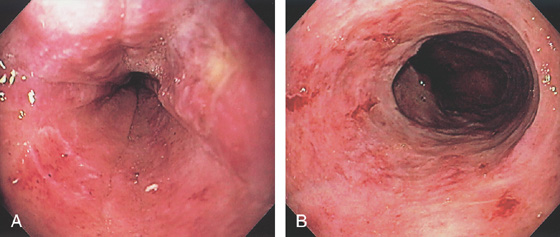

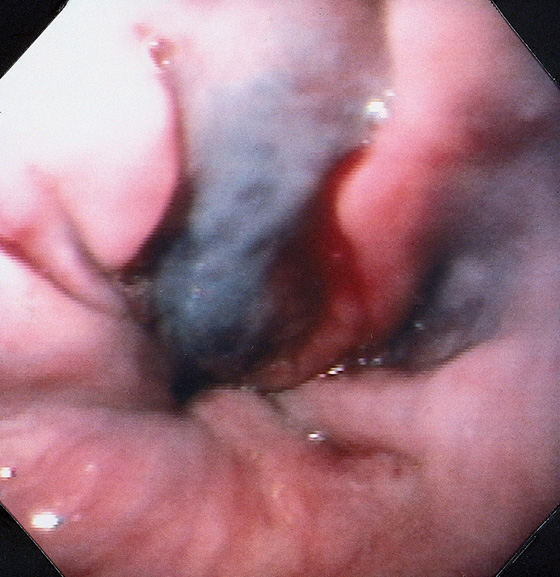

A, B, Diffuse esophagitis with focal ulceration.

C1, C2, The submucosa is infiltrated by lymphocytes. (See also Figures 1.37, 5.145, and 5.207.)

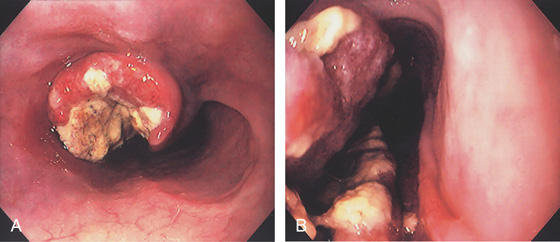

Figure 2.75 SMALL CELL CARCINOMA

A, Ulcerated heaped-up lesion in the distal esophagus. B, Close-up shows the hemicircumferential excavated lesion.

Figure 2.76 KAPOSI’S SARCOMA

A, Multiple flat, red plaques throughout the esophagus. B, Characteristic spindle cell stroma and slitlike vascular channels occupying the submucosa form a plaquelike lesion.

C, Smooth nodular lesion bulging into the esophageal lumen.

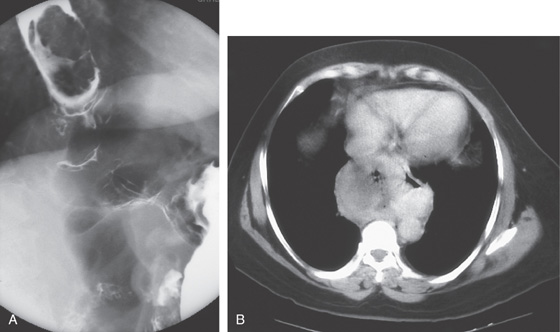

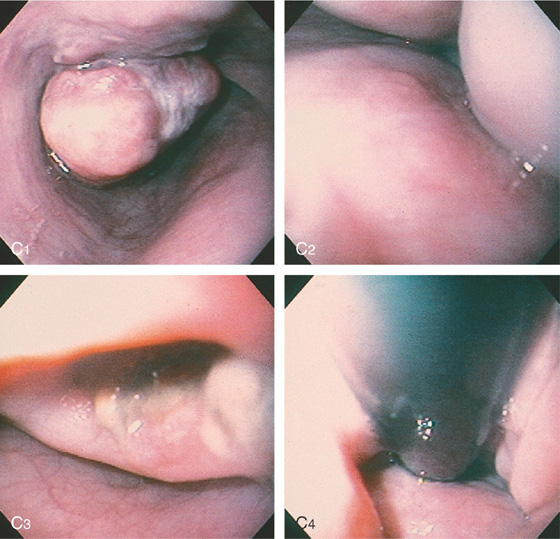

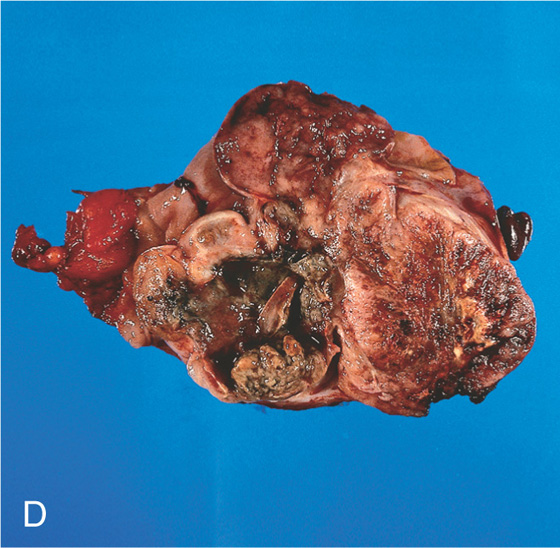

Figure 2.77 GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR (GIST)

A, Large, masslike lesion, with obliteration of the esophageal lumen. B, Large mass lesion in the midesophagus with hypodense areas, suggesting tumor necrosis or debris in the esophagus. The esophageal lumen is narrowed.

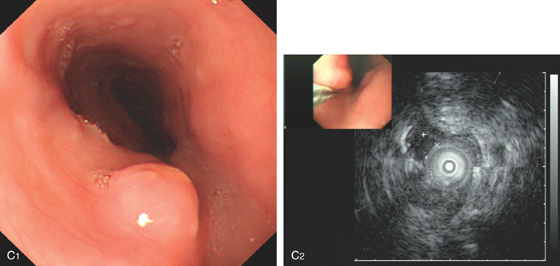

C1, Polypoid mass in the distal esophagus. Ulcer is present on the mass. C2, The distal esophageal lumen is obliterated by extrinsic compression. C3, The extrinsic compression is ulcerated. C4, Retroflex view of the proximal stomach confirms the mass lesion.

D, The resection specimen shows a bulky, necrotic polypoid lesion.

Figure 2.78 GRANULAR CELL TUMOR

A, Small, submucosal, yellowish nodule. Patient has associated reflux esophagitis. B1, B2, Raised submucosal lesion with yellowish discoloration at the mucosal surface. C, Amorphous pink material fills these large cells typical for granular cell tumors. D, Postoperative specimen shows a giant granular cell lesion. Note the yellow appearance of the tumor.

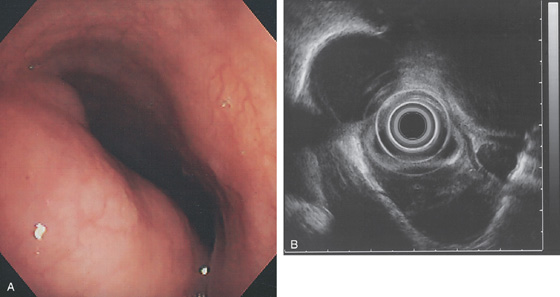

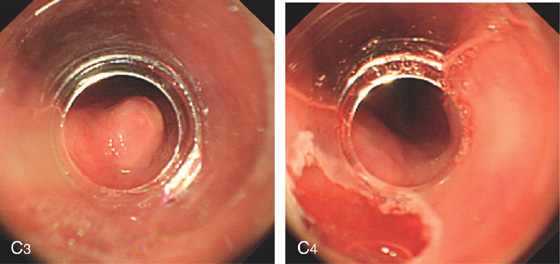

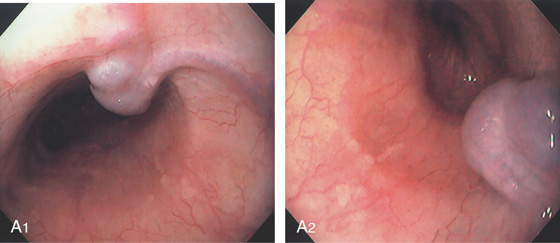

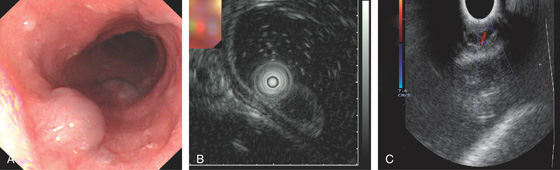

Figure 2.79 LEIOMYOMA

A, Large, submucosal, masslike lesion of the midesophagus. B, Endoscopic ultrasonography shows the lesion arises from the muscularis propria.

C1, Submucosal lesion in the proximal esophagus. C2, Endoscopic ultrasonography with a probe demonstrates the lesion arises from the muscle layer diagnostic of leiomyoma.

C3, A cap device is used for endoscopic mucosal resection. C4, Appearance of the mucosal defect after endoscopic mucosal resection.

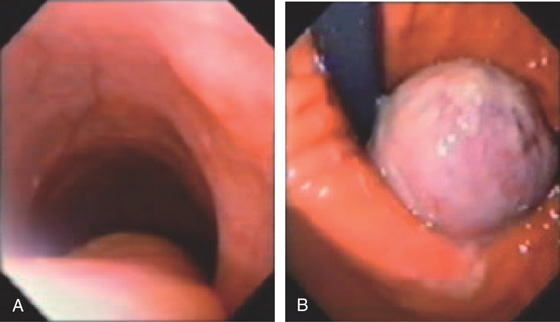

Figure 2.80 FIBROVASCULAR POLYP

A, Submucosal lesion in the midesophagus. The lesion extended to the GE junction where the polypoid nature of the lesions is appreciated on retroflexion (B). (Courtesy B. Garcia-Perez, MD, Cartagena, Spain.)

Figure 2.81 METASTATIC GASTRIC CANCER

Multiple submucosal nodules in the distal esophagus in a patient with signet ring carcinoma of the stomach.

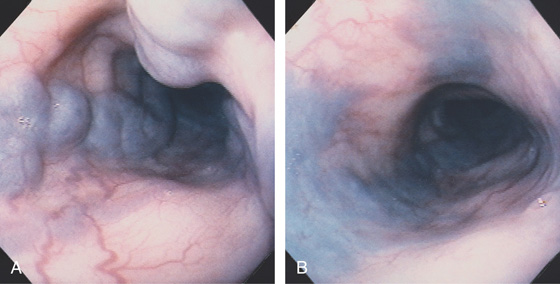

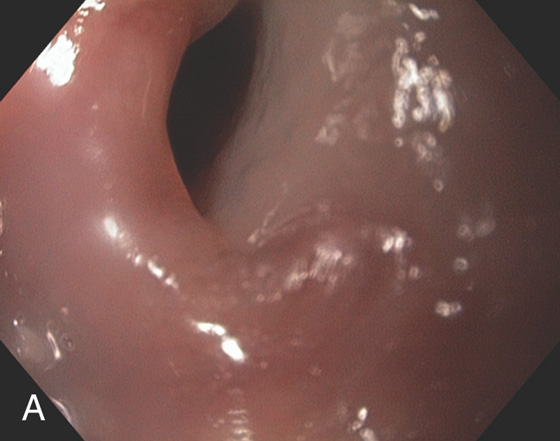

Figure 2.82 EARLY PORTAL HYPERTENSION

A, The vessels at the gastroesophageal junction are dilated and tortuous. B, With progression of portal hypertension, the varices become more apparent. The gastroesophageal junction is well demarcated, and the veins appear to originate from the gastroesophageal junction. Veins are not present in the gastric mucosa.

Figure 2.83 ESOPHAGEAL VARICES ON BARIUM ESOPHAGRAM

Tubular filling defects in the distal esophagus.

Figure 2.84 PROXIMAL VARICES

A, Small serpiginous veins in the proximal esophagus. Note the normal distal esophagus (A2). This patient had superior venacaval syndrome with marked varices on the neck and upper chest (B).

Figure 2.85 PROXIMAL ESOPHAGEAL VARICES

A, Dilated veins in the proximal esophagus. Small subepithelial vessels are also dilated and ectatic. B, With further insufflation, the esophageal veins flatten, but not completely.

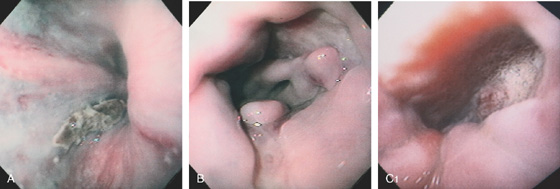

Figure 2.86 RED COLOR SIGNS

High-risk bleeding stigmata on varices include red whale signs (A, B) and hematocystic spots (C).

Figure 2.87 BLEEDING VARIX AT THE GASTROESOPHAGEAL JUNCTION

Active bleeding from this varix at the GE junction.

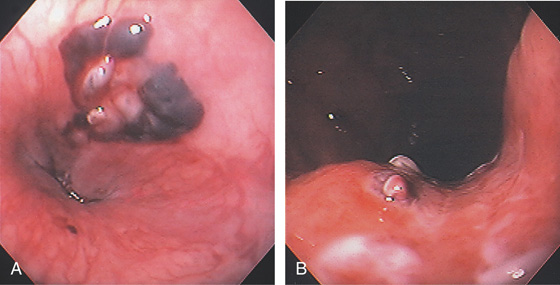

Figure 2.88 BLEEDING ESOPHAGEAL VARIX

A, Actively bleeding esophageal varix. B, Injection of sclerosant causes bleb formation, suggesting a submucosal rather than intravariceal injection. C, With further sclerotherapy, the bleeding stops; a white nipple appears at the bleeding point.

Figure 2.89 SCLEROTHERAPY-ASSOCIATED ULCERATION

A, Flat esophageal varices demonstrated by the two blue areas. One area has a yellowish plaque, representing ulceration from prior injection sclerotherapy. B, Large, irregular ulcerations in the distal esophagus. Normal-appearing mucosa is seen between the ulcers. With healing, the normal areas assume a polypoid appearance from undermining of the ulcerations. C1, Deep solitary ulcer with a central bleeding point.

C2, Large right pleural effusion was present in this patient as a complication of sclerotherapy.

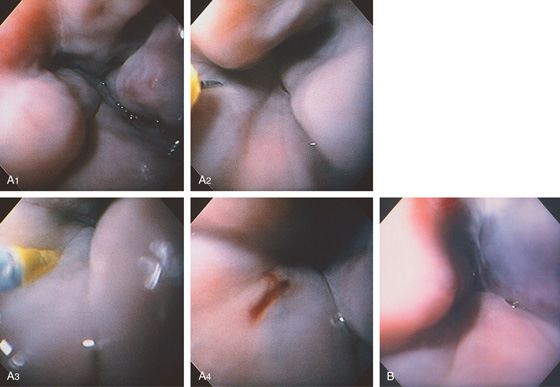

Figure 2.90 VARICEAL SCLEROTHERAPY

Varices with red color signs in the distal esophagus (A1). The sclerotherapy needle is placed into the lumen (A2) and directed toward a varix. The needle is then advanced into the varix and sclerosant is injected (A3). A small amount of oozing occurs after injection, marking the injection site (A4). B, After sclerotherapy, the varix appears to have a dark blue color.

Figure 2.91 VARICEAL SCLEROTHERAPY

After sclerotherapy, a deep bluish discoloration outlines the sclerosed varix. This color change probably represents either variceal thrombosis or stasis of blood. A small amount of blood is oozing from the injection site.

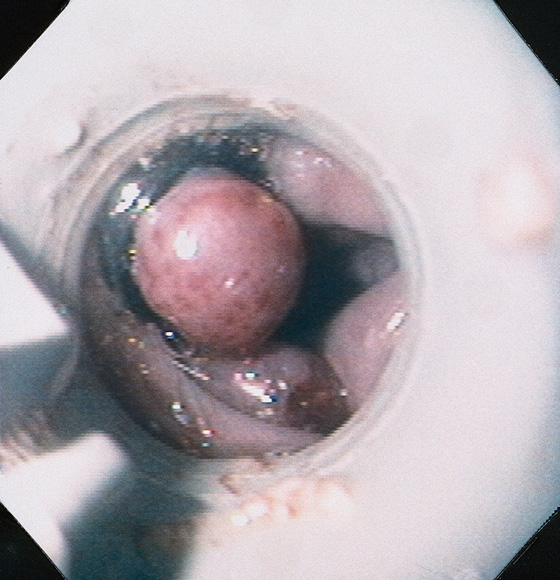

Figure 2.92 ESOPHAGEAL VARICEAL BANDING

View of an esophageal varix through an early banding device. The varix appears round, with the band encircling it. Two varices that have not been banded are on the contralateral wall.

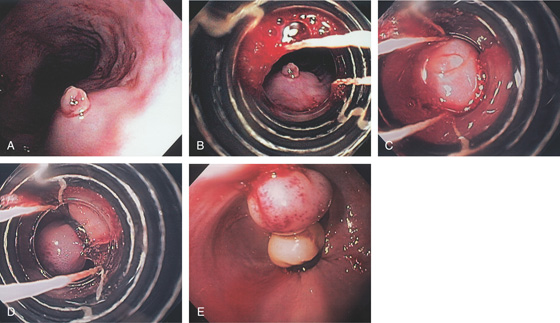

Figure 2.93 ESOPHAGEAL VARICEAL BANDING

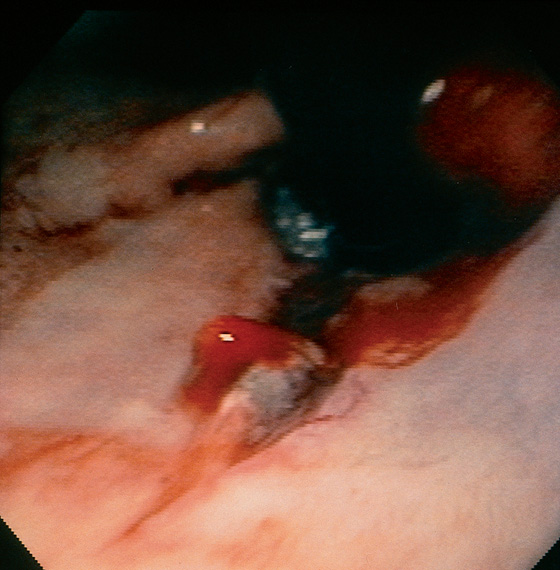

A, White nipple on the varix represents a fibrin clot at the site of recent bleeding. B, The banding device is placed just proximal to the varix. The varix is aspirated into the ligating device (C) and the band deployed (D). Multiple varices were ligated. Note the ischemic color of one varix after banding (E).

Figure 2.94 RECENT BANDING

A, Areas with the bands have spontaneously fallen off, leaving ulceration alongside persistent bands. B, More extensive ulceration at the GE junction at the site of band placement. C, Ulceration just distal to the GE junction at the site of band placement.

Figure 2.95 POST-BANDING ULCER WITH RECENT BLEEDING

Large ulceration in the distal esophagus with two flat clots at the site of bleeding from a banding-associated ulcer.

Figure 2.96 POST-BANDING SCAR

White stellate area in the distal esophagus representing a site of prior banding.

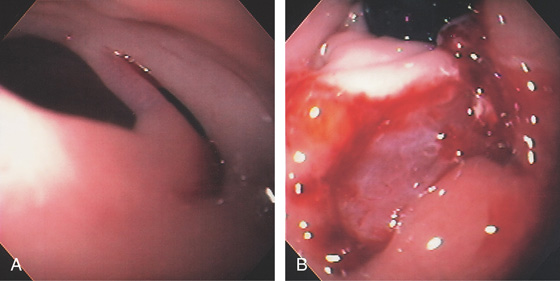

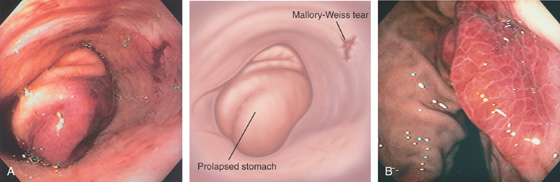

Figure 2.97 GASTRIC PROLAPSE INDUCING A MALLORY-WEISS TEAR

A, With retching, prolapse of gastric mucosa comes from the gastroesophageal junction. B, After retraction of the stomach, two areas of subepithelial hemorrhage with one small tear are seen at the gastroesophageal junction.

Figure 2.98 GASTRIC LESION ASSOCIATED WITH RETCHING

A, With repetitive emesis, gastric subepithelial hemorrhage occurs. This hemorrhagic prolapsed mucosa mimics some unusual mass lesions. A small Mallory-Weiss tear is also present on the lesser curve portion of the distal esophagus. B, With retraction of the stomach, the hemorrhagic area is well circumscribed, with accentuation of the areae gastricae.

C, Diffuse subepithelial hemorrhage of otherwise normal gastric mucosa.

Figure 2.99 ESOPHAGEAL MALLORY-WEISS TEAR

Tear at the gastroesophageal junction extending proximally, without involvement of the gastric mucosa. The base of the lesion is hemorrhagic from recent bleeding. The most common location for a Mallory-Weiss tear is on the lesser curvature side of the gastroesophageal junction.

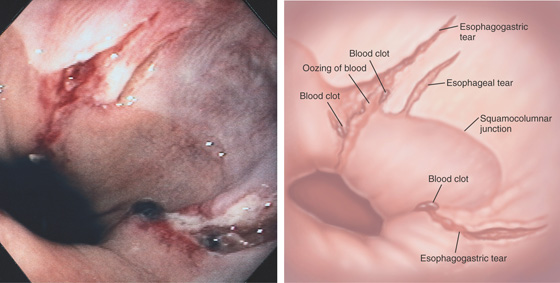

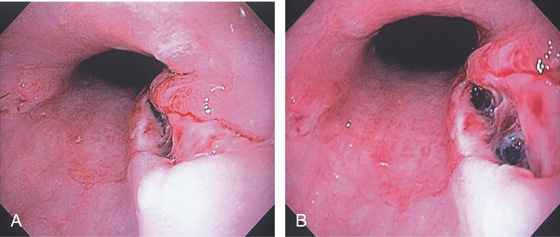

Figure 2.100 ESOPHAGOGASTRIC MALLORY-WEISS TEAR

Long, linear tear involving both the esophageal and gastric mucosae. The surrounding area is nodular, and the base of the tear is hemorrhagic. A, Linear tear along the lesser curve in the distal esophagus with heaped-up margins. B, The tear extends into a small hiatal hernia.

Figure 2.101 MALLORY-WEISS TEAR WITH FIBRIN CLOT

A, Small tear at the GE junction. B, The tear extends along the lesser curve into the cardia. Note the adherent clot. C, On close-up, a fibrin clot with active oozing is apparent.

Figure 2.102 MULTIPLE MALLORY-WEISS TEARS

Two large, deep tears involve the esophagus and stomach, with overlying blood clots. One area of active oozing is present. One smaller tear involves only the squamous mucosa.

Figure 2.103 MALLORY-WEISS TEAR AND ESOPHAGEAL HEMATOMA

A, Multiple hematomas just proximal to the GE junction on the lesser curve. B, The tear extends into the cardia along the lesser curvature. A visible vessel is present.

Figure 2.104 BLEEDING MALLORY-WEISS TEAR

Retroflex view demonstrates an irregular tear, with blood oozing from one of the margins.

Figure 2.105 MALLORY-WEISS TEAR: THERMAL PROBE THERAPY

A, Fresh blood clot and active oozing at the GE junction. B, The heater probe is used to wash the clot demonstrating active bleeding. C, The thermal probe is applied to the area, resulting in eschar and hemostasis.

Figure 2.106 HEALING MALLORY-WEISS TEAR

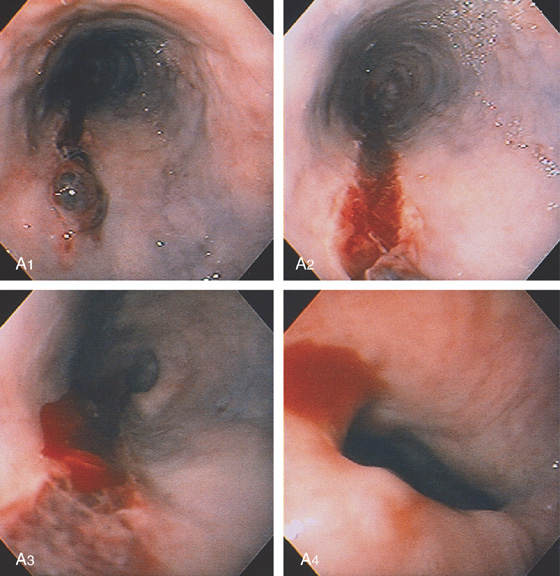

Retroflex view shows shallow exudate with surrounding subepithelial hemorrhage, characteristic of a healing Mallory-Weiss tear. The endoscopic photograph was taken 6 days after the clinical event.

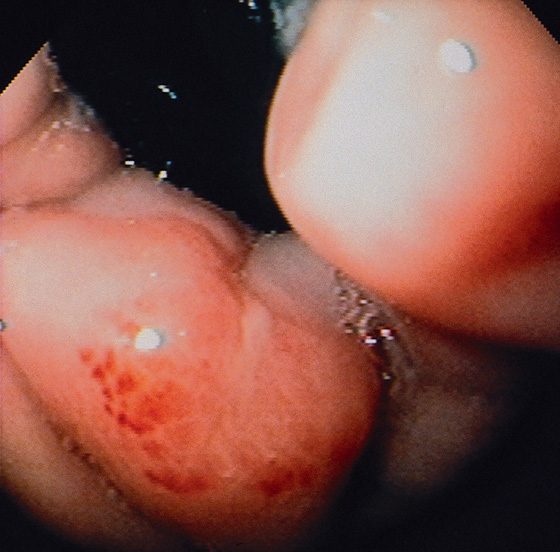

The proximal margin of the lesion has an overlying blood clot (A1). The lesion is linear with a hemorrhagic base (A2) and an active bleeding point (A3). The lesion does not extend to the gastroesophageal junction (A4).

Epinephrine and sodium morrhuate were injected into the lesion for hemostasis. After injection, a well-demarcated area with a bluish hue appeared (B1), resulting from ischemia. Note that the base of the tear is now bland (B2).

Figure 2.107 ESOPHAGEAL TEAR

C, Four days later, the esophageal mucosa appears abnormal. The tear is well shown (C1-C3), Biopsy of the mucosa demonstrated severe acute inflammation, probably resulting from ischemia secondary to the injection therapy (C4).

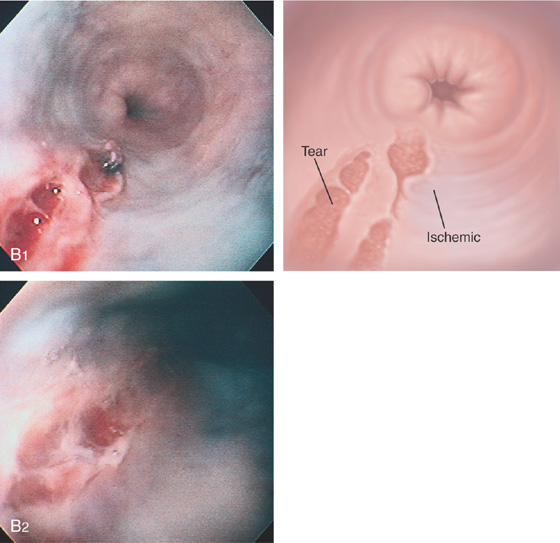

Figure 2.108 ESOPHAGEAL TEAR

A, Large tear extending proximally from the GE junction. B, The lesion is shallow with well-circumscribed margins.

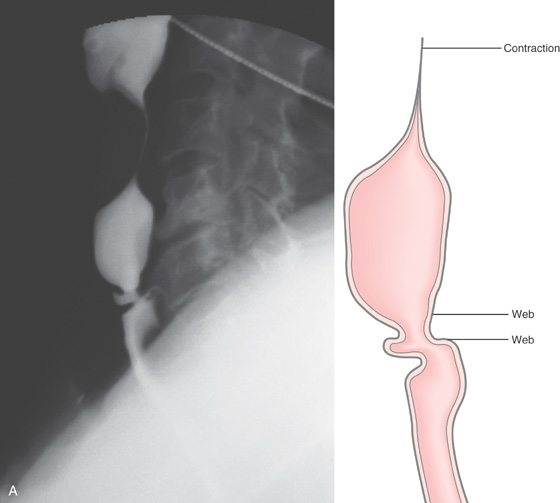

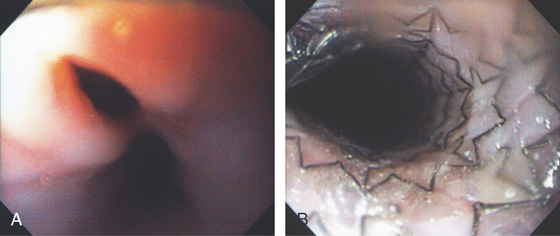

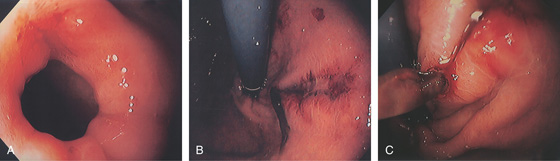

Figure 2.109 ESOPHAGEAL WEB

A, Lateral view demonstrates a short stricture with outpouching of mucosa in the middle of the stricture. An esophageal contraction is shown proximally. Two webs are present, with the distal web well visualized. Between the two webs is normal esophagus. The distal web is characterized by symmetric, circumferential narrowing of normal-appearing mucosa.

B, Web just distal to the upper esophageal sphincter. C, After dilatation, a tear is evident.

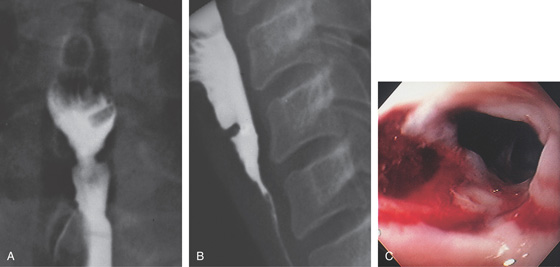

Figure 2.110 ESOPHAGEAL WEB IN PLUMMER-VINSON SYNDROME

A, Anteroposterior view shows the compromised luminal diameter. B, Lateral projection demonstrates a thick web just distal to the cricopharyngeus. C, Tight stricture with Candida esophagitis resulting from stasis.

Figure 2.111 PROXIMAL ESOPHAGEAL STRICTURE

A, Tight ringlike stricture in the proximal esophagus. B, A Savary guidewire is passed through the stricture. C, Tearing of the stricture after dilatation.

Figure 2.112 ESOPHAGEAL RINGS

A, Multiple rings in the midesophagus.

B, Endoscopically, the rings have a semilunar appearance.

Figure 2.113 CHRONIC GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST DISEASE

A, Ring in the midesophagus. B, When passing the endoscope through the area, the mucosa peels away. C, Multiple rings with a thickened textured appearance.

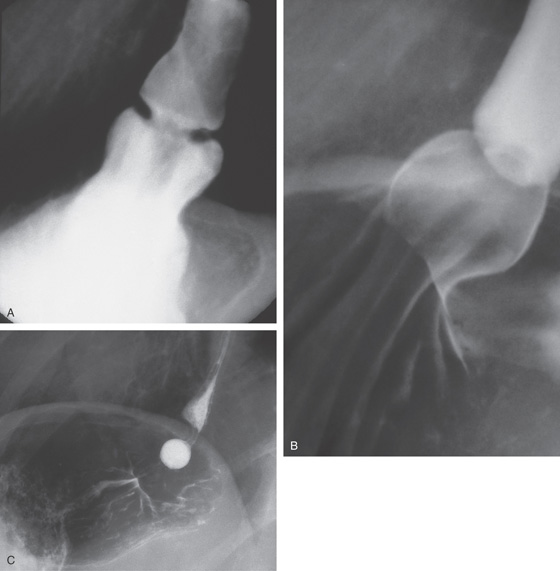

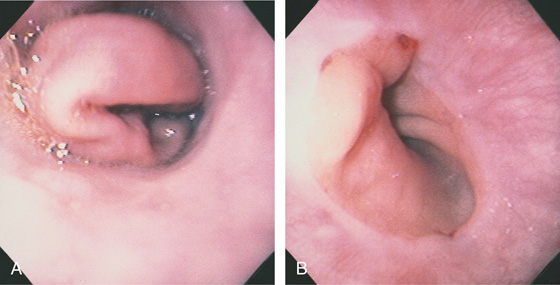

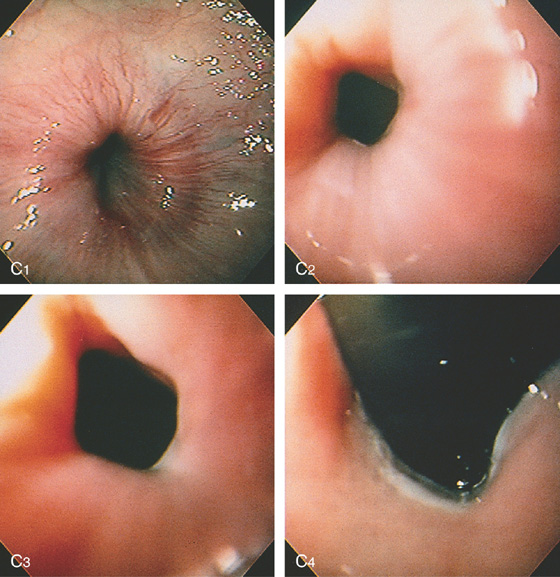

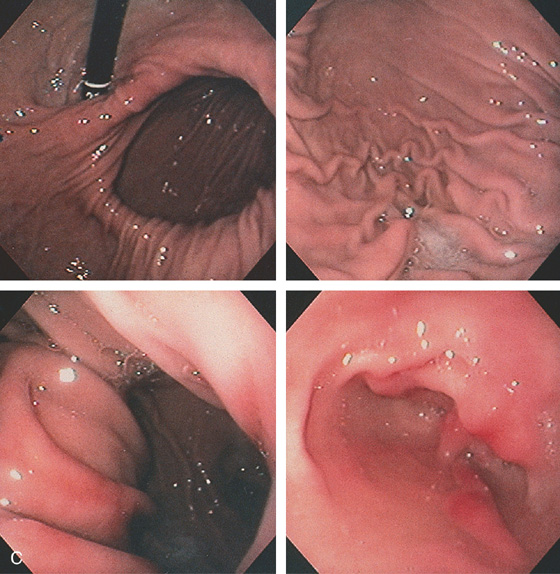

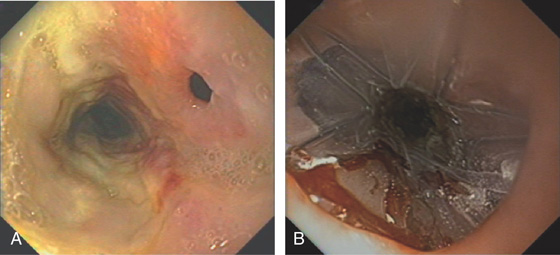

Figure 2.114 SCHATZKI’S RING

A, Circumferential, smooth narrowing proximal to a hiatal hernia. B, Close-up view demonstrates the hiatal hernia with gastric folds radiating toward the stricture. C, A 12.5-mm tablet is delayed at the level of the stricture.

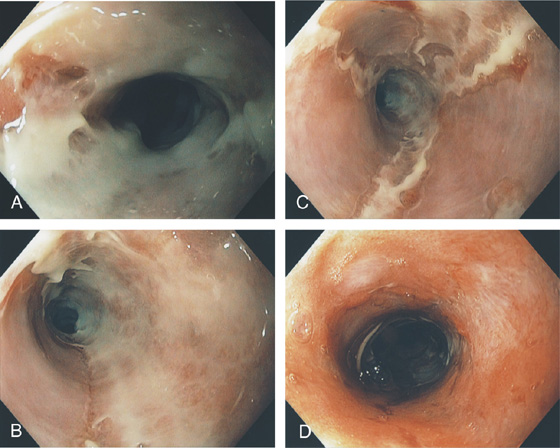

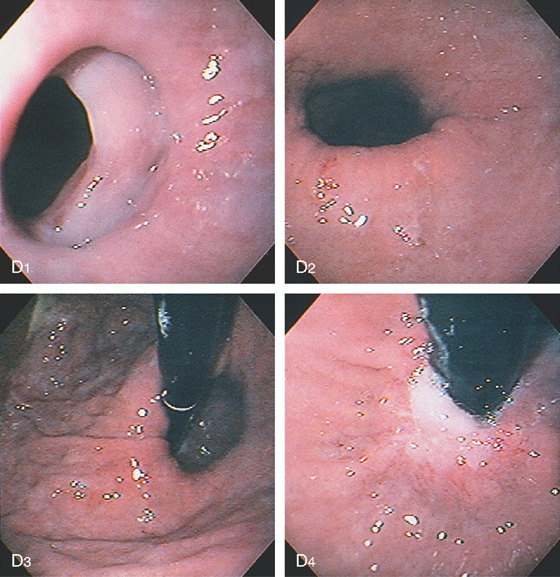

Figure 2.114 SCHATZKI’S RING

Circumferential, smooth stricture at the gastroesophageal junction, characteristic of a Schatzki’s ring. The surrounding esophageal mucosa is normal (D1). The hiatal hernia is distal to the stricture (D2) and by retroflexion (D3, D4). Retroflex view in the hiatal hernia demonstrates squamous mucosa tightly encircling the endoscope (D4).

E, After passage of a 60 French Maloney dilator, a tear can be seen in the stricture.

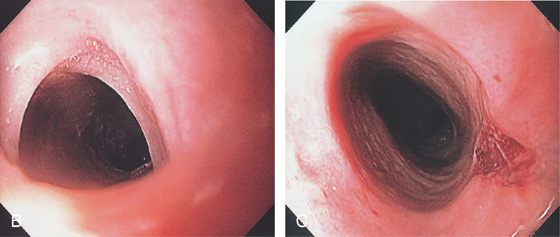

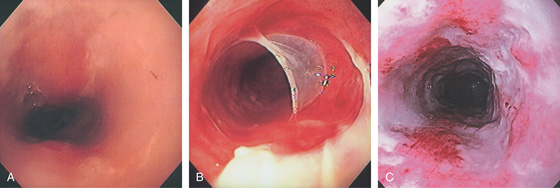

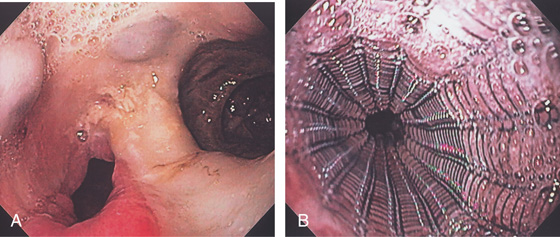

Figure 2.115 SCHATZKI’S RING

A, Typical-appearing ring as shown on standard endoscopy. B, High-definition and (C) narrow band imaging.

Figure 2.116 TEARING OF A SCHATZKI’S RING

A1, A2, Tight ring at the gastroesophageal junction on antegrade and retrograde views. B1, B2, After Maloney dilation, a large tear with a flap of squamous tissue is shown. C, Linear ulceration and hematoma are shown more proximally.

Figure 2.117 RADIATION ESOPHAGITIS

A, Diffuse exudate of the midesophagus. B, With passage of the endoscope, the mucosa peels away. C, Diffuse exudate with ulceration representing the site of prior tumor.

Figure 2.118 RADIATION STRICTURE

A, A short, smooth narrowing in the proximal esophagus. The esophagus is dilated proximal to the stricture.

B, The short, smooth stricture is shown. The surrounding mucosa has a tan appearance, suggestive of fibrosis.

Figure 2.119 ANASTOMOTIC STRICTURE

A, A short, smooth stricture proximal to the gastric pull-up, after resection for carcinoma. Multiple surgical clips are present. B, The stricture is smooth, without ulceration or tumor. Surgical clips and sutures are shown.

Figure 2.120 BARRETT’S STRICTURE

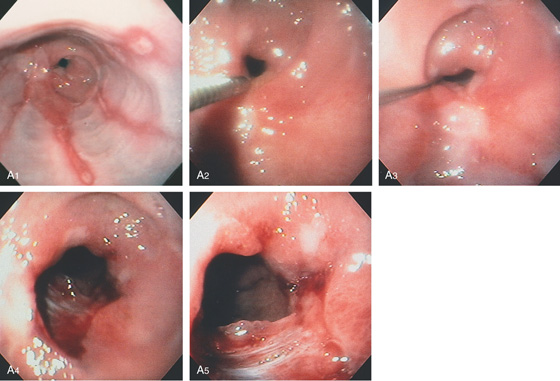

A1, Linear erosions are emanating from the stricture. The mucosa at the stricture has a textured orange color. These findings suggest reflux-associated Barrett’s esophagus. A2, The tip of the guidewire is just proximal to the stricture. A3, The guidewire is then passed blindly through the stricture. A4, After passage of Savary dilators, a tear is seen in the stricture. A5, The base of the stricture has a fibrotic appearance.

Figure 2.120 BARRETT’S STRICTURE

B1, Irregular stricture in the proximal esophagus. B2, The distal esophageal mucosa has a fine granular appearance. Free reflux is seen to the level of the stricture. A hiatal hernia is also present. These radiographic findings are compatible with a Barrett’s stricture. The mucosa of the distal esophagus is granular as the squamous mucosa is replaced by gastric mucosa. B3, There is nodularity at the level of the stricture and active ulceration. The orange ulcerated mucosa extending proximally from the stricture contained gastric mucosa on biopsy.

Figure 2.120 BARRETT’S STRICTURE

B4, The stricture has been dilated (top left). The mucosa distal to the stricture has an orange color with a few erosions (top right, bottom left), and a large hiatal hernia is present (bottom right). Biopsy of the mucosa distal to the esophageal stricture consisted of normal gastric (body-type) tissue.

Figure 2.121 STRICTURE DILATATION WITH CREATION OF FISTULA

A, Slitlike area alongside a Schatzki’s ring. B, Retroflex view shows tearing representing creation of a fistula alongside the ring. Dilatation was performed with a Maloney bougie.

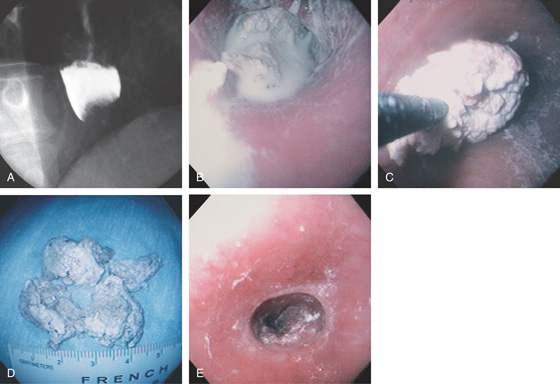

Figure 2.122 FOOD BOLUS IMPACTION

A, Acute dysphagia resulted after the patient swallowed a large piece of meat at a steakhouse. Barium can be seen overlying a filling defect at the gastroesophageal junction, with mild dilation proximally. B, Barium coats the food bolus. C, The large meat bolus is being extracted with the forceps grabber up to an overtube. D, After extraction, multiple large pieces of meat are identified. E, A slight area of narrowing is seen at the gastroesophageal junction, which, although nonobstructing, caused the impaction. Many patients with food bolus esophageal impaction have an underlying esophageal stricture, although, as shown in this case, it can be very mild. A 60 French Maloney dilator was then passed to treat the stricture.

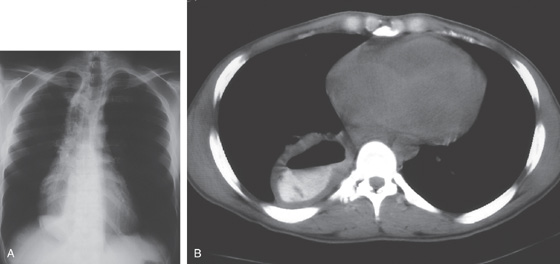

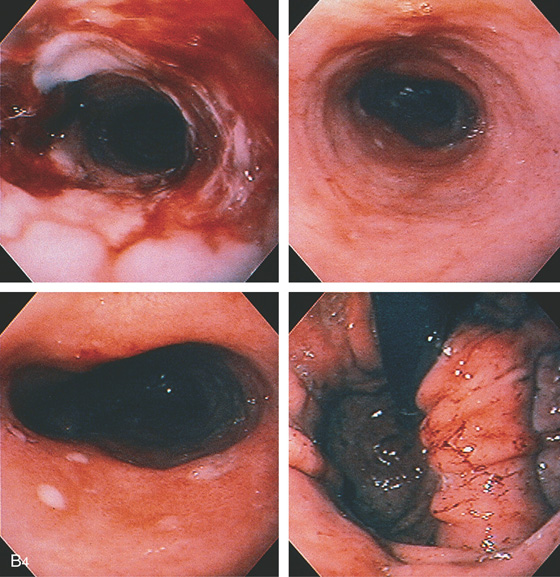

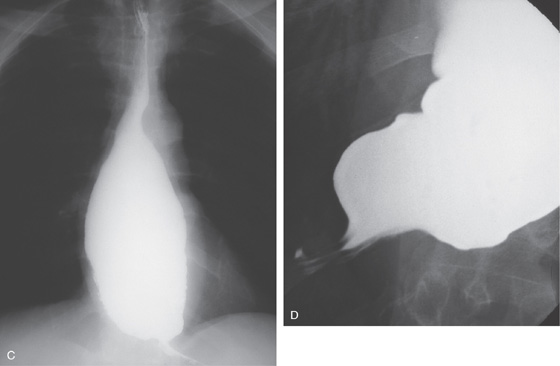

Figure 2.123 ACHALASIA

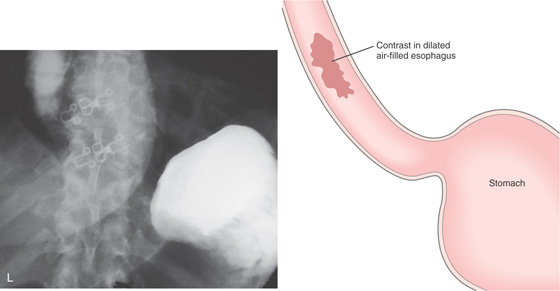

A, The mediastinum is widened, with a large air-fluid level. B, The massively dilated esophagus is filled with barium. Note the thickening of the esophageal wall.

C, The dilated esophagus is well visualized on the anteroposterior view of the chest. D, The massively dilated esophagus tapers to a “bird’s beak,” suggestive of achalasia. During observation of the esophagus under fluoroscopy, there were noted to be tertiary contractions but poor peristalsis.

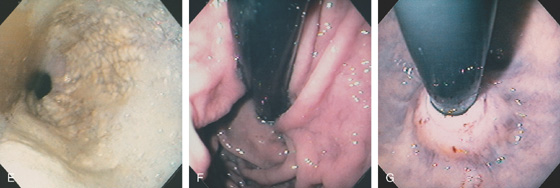

Figure 2.123 ACHALASIA

E, On endoscopic examination, the esophagus is found to be dilated, with puddling of fluid. The thick white mucosa and yellow plaques represent Candida esophagitis, resulting secondarily from stasis of esophageal contents. F, Retroflex view of the gastric cardia demonstrates no mass lesion. G, Close-up view of the gastroesophageal junction shows mucosa tightly encircling the endoscope. The mucosa appeared to bulge when the endoscope was advanced.

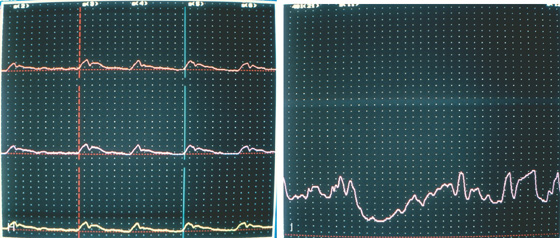

H, Esophageal motility is poor, with reduced amplitude and absence of peristaltic waves. I, The lower esophageal sphincter does not totally relax.

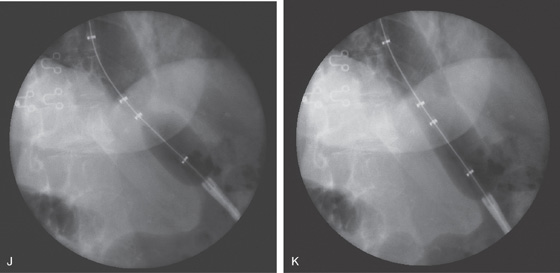

J, The Microvasive 35-mm balloon is passed across the stricture and inflated. A “waist” is shown, representing the gastroesophageal junction. K, With full insufflation of the balloon, the “waist” is obliterated, indicating successful dilation.

Figure 2.123 ACHALASIA

L, After dilation, oral contrast material is swallowed, filling the dilated distal esophagus; however, contrast now enters the stomach. No evidence of extravasation is present.

Figure 2.124 ACHALASIA TEAR POSTDILATATION

Deep mucosal defect just proximal to the GE junction.

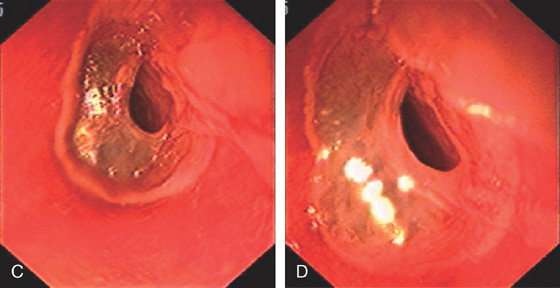

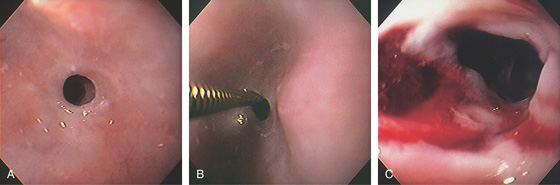

Figure 2.125 BOTOX INJECTION IN ACHALASIA

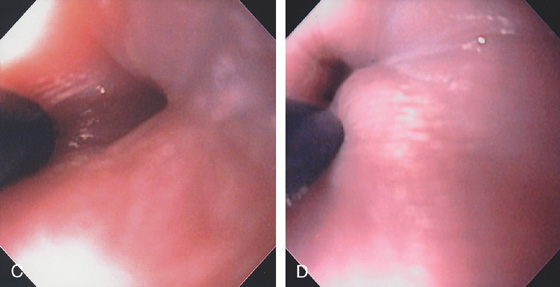

A, Dilated esophagus filled with fluid and debris. B, Tight GE junction.

C, D, Injection is made with a sclerotherapy needle in a circumferential fashion at the GE junction using an antegrade approach.

Figure 2.126 ACHALASIA COMPLICATED BY SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

Hemicircumferential raised ulcerative lesion in the distal esophagus. Note the esophagus is dilated.

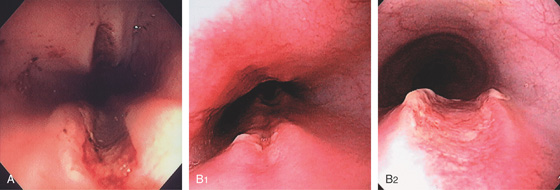

Figure 2.127 HYPERTENSIVE LOWER ESOPHAGEAL SPHINCTER

A, Smooth narrowing at the gastroesophageal junction, suggesting achalasia. The esophagus is dilated. B, Only a small amount of barium passes into the stomach.

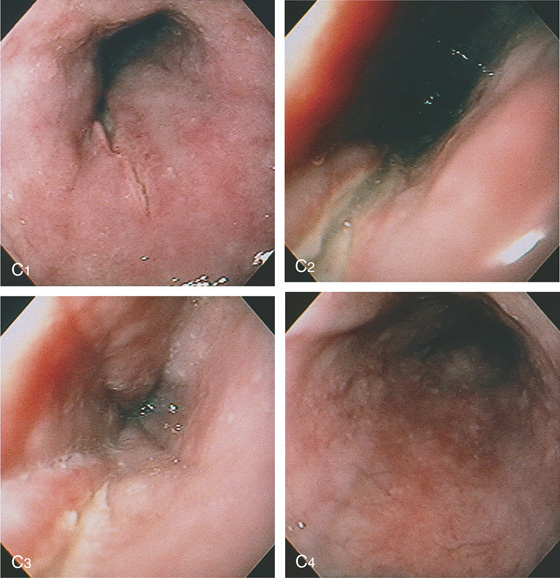

C1, The lower esophagus appears to be wrapped tightly around a doughnut; the gastroesophageal junction appears to have a smooth narrowing, although the endoscope passed with slight pressure (C2, C3). Retroflex view of the gastroesophageal junction is normal (C4). A motility study demonstrated an increased lower esophageal sphincter pressure, with normal relaxation and esophageal peristalsis.

Figure 2.128 DRUG-INDUCED ESOPHAGITIS

A, Hemicircumferential exudate at the GE junction caused by alendronate. B, Several shallow ulcers in the midesophagus caused by aspirin. C, Multiple lesions in the midesophagus caused by doxycycline.

Figure 2.129 DRUG-INDUCED ESOPHAGEAL ULCER

A, Well-circumscribed ulcer, with a distal fold radiating to the lesion. The surrounding mucosa appears normal. B, Large hemicircumferential esophageal ulceration. The surrounding esophageal mucosa and distal esophagus appear normal. Odynophagia resulted several weeks after beginning doxycycline therapy. C, Healing of the ulceration shows the demarcated area now reepithelialized, with a normal vascular pattern.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Drug-Induced Esophageal Ulcer (Figure 2.129)

Cytomegalovirus esophagitis

Herpes simplex virus esophagitis

Human immunodeficiency virus-associated idiopathic esophageal ulcer

Other infections

Figure 2.130 HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS-ASSOCIATED IDIOPATHIC ULCER

Multiple well-circumscribed ulcerations throughout the esophagus. The ulcers have a punched-out appearance, with normal-appearing intervening mucosa. The ulcers seem to be raised above the normal level of the esophageal wall, resulting in this heaped-up appearance.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Idiopathic Ulcer (Figure 2.130)

Cytomegalovirus esophagitis

Herpes simplex virus esophagitis

Histoplasmosis

Drug-induced esophagitis

Other infections

Figure 2.131 HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS-ASSOCIATED IDIOPATHIC ULCER

A, Marked abnormality of the gastroesophageal junction, suggestive of ulceration. B, Barium is refluxing into the more proximal esophagus. The combination of these two radiographic findings suggests reflux disease.

Figure 2.131 HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS-ASSOCIATED IDIOPATHIC ULCER

C, Large, deep ulceration extending from the distal esophagus to the gastroesophageal junction (C1-C3), where the ulcer becomes hemicircumferential (C3-C4). The ulcer base has an irregular appearance. D, Retroflex view into the ulcer demonstrates the depth of the lesion. E, After oral steroid therapy, the ulceration has completely reepithelialized.

Figure 2.132 HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS-ASSOCIATED IDIOPATHIC ULCER

A, Large, well-circumscribed, heaped-up ulcer in the midesophagus. B, Multiple deep ulcers in the esophagus. C1, C2, Deep ulcer at the GE junction with creation of a fistula to the stomach. Note the slit in the cardia representing the fistula into the stomach (C3).

Figure 2.133 NASOGASTRIC TUBE ULCER

A, Linear “kissing” ulcers in the midesophagus associated with long-standing nasogastric tube placement. B1, B2, Linear ulcer with raised appearance of the midesophagus. The most distal portion has a raised appearance to the edges.

Figure 2.134 CROHN’S DISEASE

A, Multiple shallow, well-circumscribed ulcers in the midesophagus. B, Healing of the ulcers after corticosteroid therapy.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Crohn’s Disease (Figure 2.134)

Cytomegalovirus esophagitis

Herpes simplex virus esophagitis

Pill-induced esophagitis

Figure 2.135 ESOPHAGEAL SARCOIDOSIS

A, Multiple pinpoint raised whitish areas. B, Biopsy confirmed granulomatous esophagitis.

Figure 2.136 INLET PATCH

A, Distal to the cricopharyngeus, a well-circumscribed area with an orange color is shown. The surrounding esophageal mucosa has the typical pearly white appearance of squamous mucosa. B, Close-up view of the patch. C, Large area of involvement. D, The inlet patch has a raised appearance. E, This area represents heterotopic gastric mucosa. Normal squamous epithelium is on the right, with gastric mucosa and typical-appearing fundic glands on the left.

Figure 2.137 SLOUGHING ESOPHAGITIS

Normal-appearing squamous mucosa appears to be peeling away from the mucosal surface. Note the underlying mucosa is normal.

Figure 2.138 LICHEN PLANUS

A, Narrowing at the GE junction.

B-D, The mucosa is easily detached from the underlying mucosa.

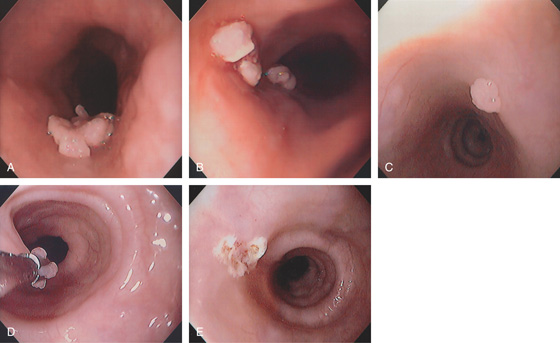

Figure 2.139 SQUAMOUS PAPILLOMA

Verrucous-appearing lesion in the midesophagus.

Figure 2.140 SQUAMOUS PAPILLOMA

A, Large verrucous plaquelike lesion. B, Multiple smaller lesions were more distal. C, Solitary verrucous lesion in the midesophagus. The lesion is grasped with a hot biopsy forcep and ablated (D), and the area coagulated (E).

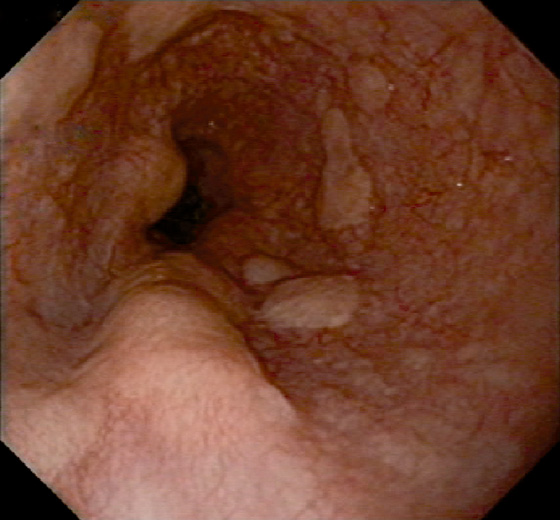

Figure 2.141 GLYCOGENIC ACANTHOSIS

Multiple slightly raised, yellowish lesions are seen throughout the esophagus.

Figure 2.142 GLYCOGENIC ACANTHOSIS

A, Solitary white lesion in the distal esophagus. B, Large, flat, white lesion in the midesophagus. This patient had multiple lesions.

Figure 2.143 PARAKERATOSIS

A1, A2, Marked thickening and plaquelike appearance of the squamous mucosa in the distal esophagus. These lesions can result from stasis such as in achalasia or obstruction from other causes.

B1, B2, Increased thickness of the stratum corneum with spindle-shaped cells and condensed nuclei.

Figure 2.144 HYPERKERATOSIS OF THE ESOPHAGUS

A, B, Multiple whitish plaques throughout the distal esophagus, some of which are confluent.

C, D, Biopsy of the lesion shows squamous mucosa with thickening of the superficial squamous mucosa, granular cell formation, parakeratosis, and focal papillomatosis.

E, Close-up shows the marked thickening of the superficial mucosa.

Figure 2.145 VASCULAR LESION

This well-circumscribed lesion bulges into the esophageal lumen. The overlying mucosa is normal and has a red discoloration, typical of a vascular anomaly.

Figure 2.146 VASCULAR LESION

A1, A2, Venous bleb in the midesophagus.

Figure 2.147 HEMANGIOMA

A, Submucosal vascular lesion. B, Endoscopic ultrasonography characterizes the lesion. C, Doppler probe of the lesion confirms arterial flow.

Figure 2.148 BLUE RUBBER BLEB NEVOUS SYNDROME

Focal venous bleb in the distal esophagus.

Figure 2.149 VASCULAR ECTASIA

Pinpoint ectasia at the GE junction in a patient with Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome.

Figure 2.150 ESOPHAGEAL DIVERTICULA

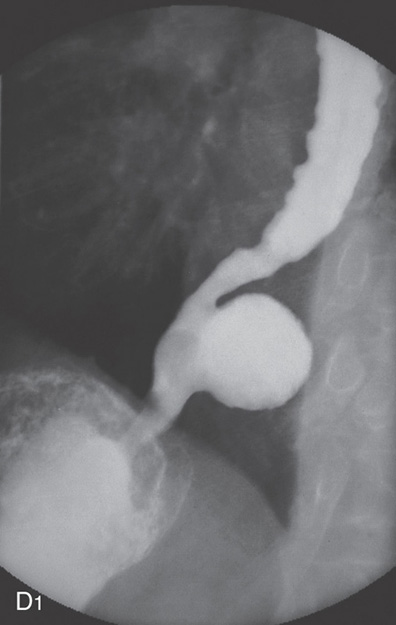

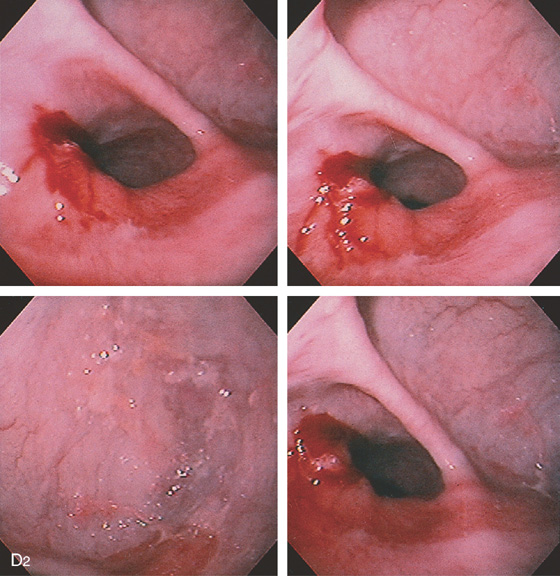

A, Zenker’s diverticulum. A1, A2, Barium swallow both on anteroposterior and lateral view shows typical location of the diverticulum, which is filled with barium.

A3, Debris-filled cavity posterior to the trachea. A4, Debris-filled cavity. A5, A guidewire is in the esophagus at the level of the cricopharyngeus, with the arytenoids visible. This lesion results from outpouching of hypopharyngeal mucosa between the oblique fibers of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle and the transverse fibers of the cricopharyngeus. This area of thin muscular wall is termed Killian’s triangle.

Figure 2.150 ESOPHAGEAL DIVERTICULA

B, Cervical esophageal. B1, A large diverticulum is present, distal to the cricopharyngeus. B2, The diverticulum is filled with Candida, food debris, and a pill. C, Midesophageal. C1, Diverticulum in the midesophagus, usually termed a traction diverticulum. C2, The diverticulum projects laterally. C3, Midesophageal diverticulum with exudate at the base.

Figure 2.150 ESOPHAGEAL DIVERTICULA

D, Epiphrenic. D1, Epiphrenic diverticulum and tertiary esophageal contractions.

D2, A large diverticulum proximal to the gastroesophageal junction is present on the right, with the normal esophageal lumen on the left. The size of the diverticulum is appreciated (bottom left). Gastric tissue appears to enter the diverticulum (right). Fresh blood is seen across the gastroesophageal junction resulting from a Mallory-Weiss tear (bottom right).

Figure 2.151 ESOPHAGEAL DIVERTICULUM

Outpouching in the distal esophagus.

Figure 2.152 INTRAMURAL PSEUDODIVERTICULOSIS

A, Multiple small collections of barium immediately lateral to the esophageal wall. B, The barium collections represent these round defects in the esophageal wall. The base of the lesions does not have a granular appearance suggestive of ulceration.

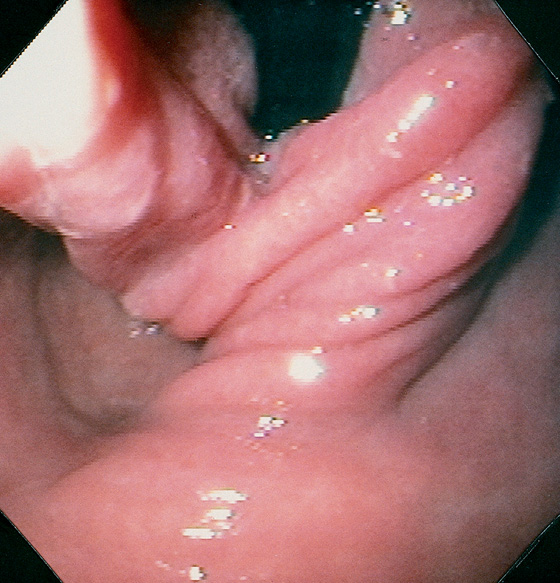

Figure 2.153 HIATAL HERNIA

A, The gastroesophageal junction is patulous, outlined by the borders of the squamous and gastric mucosae. The diaphragmatic impression is shown. B, Retroflex view demonstrates the diaphragmatic impression, with the gastric mucosa proximal. There is no apposition of the esophageal mucosa around the endoscope.

C, A portion of the stomach is in the chest.

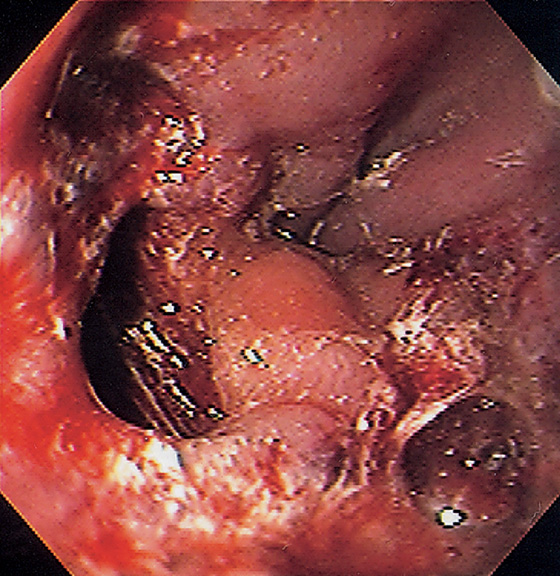

Figure 2.154 PARAESOPHAGEAL HERNIA

A, The mediastinum is widened by a large gastric air bubble. B, Upper gastrointestinal barium study demonstrates that the air bubble represents a significant portion of the stomach in the chest cavity.

C, On retroflex view, a large defect is next to the endoscope extending proximally (top left). The defect is entered, and typical gastric mucosa is shown (top right). With further advancement of the endoscope, an area of impingement is seen encircling the stomach. More gastric mucosa is in the distance (bottom left). With further advancement, the antrum is shown, as evidenced by the loss of gastric rugae (bottom right).

Figure 2.155 NISSEN FUNDOPLICATION

The gastric mucosa tightly encircles the endoscope as if it were twisted.

Figure 2.156 FAILED NISSEN FUNDOPLICATION

Although the gastric mucosa has a twisted appearance, the endoscope is now free, with loss of competence.

Figure 2.157 CAUSTIC INGESTION

A1, After the ingestion of acid, the squamous mucosa sloughs in a linear pattern. The mucosa is edematous and has a bluish discoloration. A2, The gastric mucosa is hemorrhagic and edematous. B, Diffuse shallow ulceration with exudate coating the esophagus.

Figure 2.158 CAUSTIC INGESTION

A, Diffuse ulceration of the hypopharynx. Note the presence of an endotracheal tube. B, Just distal to the upper esophageal sphincter the mucosa is denuded and there is a peculiar vascular pattern. C, More distally, the vascular pattern apparently represents the submucosa as there is a deep ulcer with sparing of the contralateral wall. D, Exudative esophagitis is present in the distal esophagus but without deep ulceration. E, The stomach is spared. F, At 4 days, the hypopharynx is much improved with erosion, and edema is seen at the arytenoids.

Ulceration is more extensive at the upper esophageal sphincter (G). H, The area of hemicircumferential ulceration (C) is now more clearly demarcated. I, At 7 days, ulceration and edema are still present in the hypopharynx. Note the presence of a feeding tube. J, Severe ulceration is still present in the proximal esophagus.

Figure 2.159 CAUSTIC INGESTION IN COLONIC INTERPOSITION

A, Diffuse edema of the hypopharynx and arytenoids. B, Diffuse ulceration is present in the colon. C, There is sparing of the colonic–gastric anastomosis.

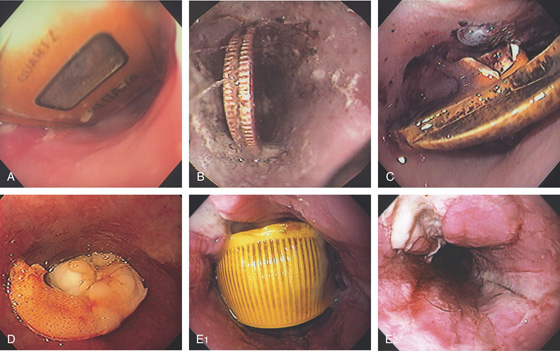

Figure 2.160 FOREIGN BODIES

A variety of foreign bodies are present in the esophagus, including a watch (A), quarters (B), PEG tube bumper (C), and shrimp (D). E1, Bottle cap. E2, After removal, extensive ulceration is evident.

Figure 2.161 BLOM-SINGER PROSTHESIS

The plastic prosthesis enters anteriorly and fits tightly into the esophagus. This prosthesis enters the esophagus through the trachea and is used for speech after tracheostomy.

Figure 2.162 CYSTIC ESOPHAGEAL LESION

A, Well-circumscribed, smooth filling defect in the distal esophagus.

Figure 2.162 CYSTIC ESOPHAGEAL LESION

B, The filling defect appears round and smooth, with overlying normal-appearing mucosa. This can be seen both antegrade (B1) and retrograde (B2, B3). The lesion is soft and collapses when probed with the biopsy forceps (B4).

C, Multiple cystic-appearing lesions in the midesophagus.

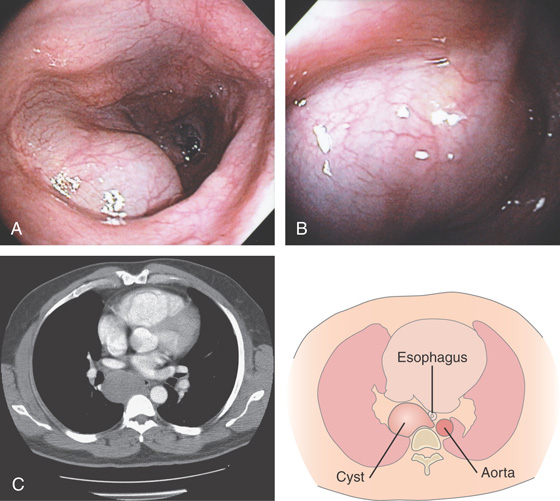

Figure 2.163 PARAESOPHAGEAL CYST

A, B, Cystic impression in the midesophagus. C, Large cystic lesion in the mediastinum impinging on the esophagus.

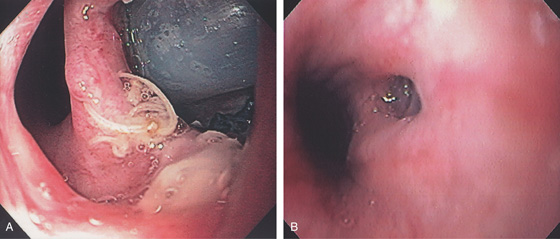

Figure 2.164 TRACHEAL–ESOPHAGEAL FISTULA

A, A communication is present in the midesophagus, with outline of the trachea.

Figure 2.164 TRACHEAL–ESOPHAGEAL FISTULA

B1, B2, A stricture is present proximal to the fistula. Beyond the stricture, the large fistula is apparent (B3, B4), with tracheal rings at the level of the carina (B4).

Figure 2.165 TRACHEAL–ESOPHAGEAL FISTULA

A, Erosion of endotracheal tube into the esophagus. B, A tracheoesophageal fistula resulted from radiation therapy for lung cancer.

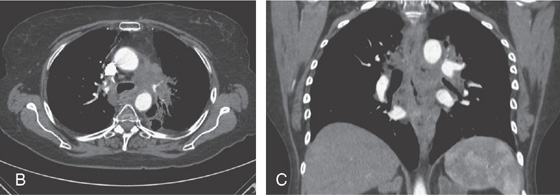

Figure 2.166 TRACHEAL–ESOPHAGEAL FISTULA CAUSED BY LUNG CANCER

A, Small fistulous opening identified. B, A fully covered esophageal stent has been placed.

Figure 2.167 FISTULA AFTER RADIATION THERAPY

A, Fistula easily seen. B, A covered stent has been deployed across the opening.

Figure 2.168 STENTING OF TRACHEOESOPHAGEAL FISTULA FROM LUNG CANCER

A, Large fistula in the midesophagus from lung cancer. B, Placement of coated metallic stent.

Figure 2.169 TRACHEOESOPHAGEAL FISTULA CAUSED BY LUNG CANCER

A, Large, deep ulceration of the midesophagus.

B, C, CT scans shows the large mass lesion that involves the esophagus.

Figure 2.170 ULCER INVOLVING MEDIASTINUM

A, Large idiopathic esophageal ulcer of AIDS in the distal esophagus. B, Close-up shows the depth of the lesion. Biopsy showed lung tissue.

Figure 2.171 POSTSURGICAL FISTULA

A, Large opening in the midesophagus connecting to the mediastinum. B, Metallic suture is present with neovascularization.

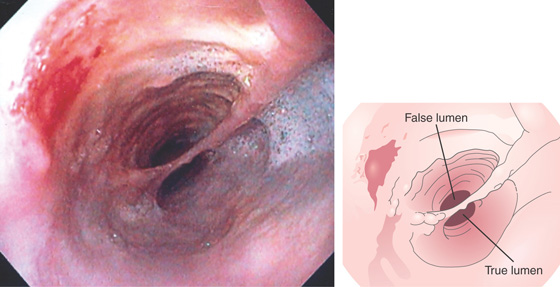

Figure 2.172 DOUBLE-BARREL ESOPHAGUS

Two distinct esophageal lumens are visible. Such a lesion is typically caused by some type of trauma creating a false lumen. In this case, the false lumen is in the superior location.

Figure 2.173 EXTRINSIC LESION

A, Tubular extrinsic compression in the midesophagus in a patient after pneumonectomy. B, Endoscopic ultrasonography confirms the extrinsic compression to be the aorta.