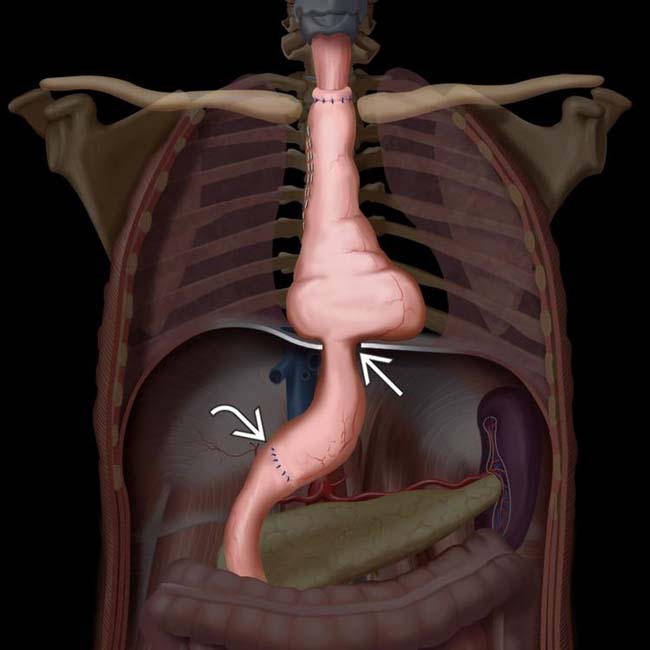

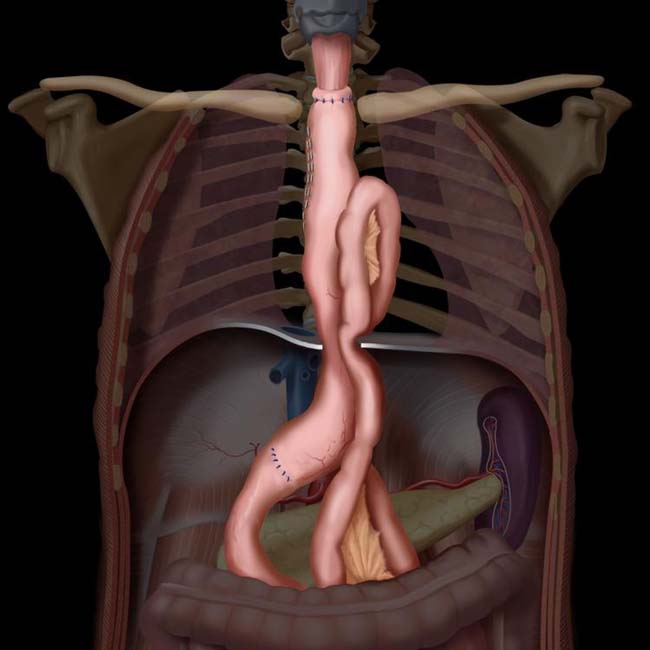

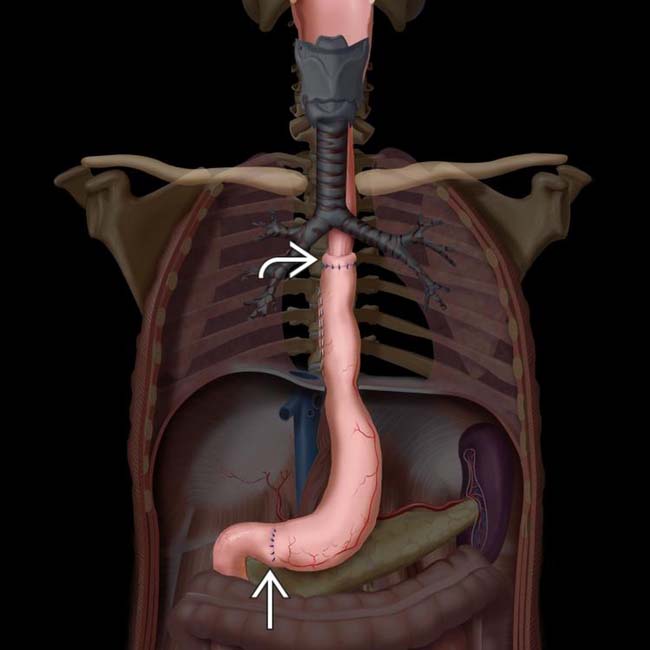

Transthoracic esophagectomy: Usually performed through right intercostal approach (Ivor Lewis procedure)

• Stomach is ideal conduit, as it has reliable blood supply and can reach high into thorax or neck for anastomosis

• Postoperative complications

Essentially all patients have some degree of dysphagia, early satiety, and reflux following esophagectomy

Essentially all patients have some degree of dysphagia, early satiety, and reflux following esophagectomy

Essentially all patients have some degree of dysphagia, early satiety, and reflux following esophagectomy

Essentially all patients have some degree of dysphagia, early satiety, and reflux following esophagectomy

is done to facilitate gastric emptying.

is done to facilitate gastric emptying.

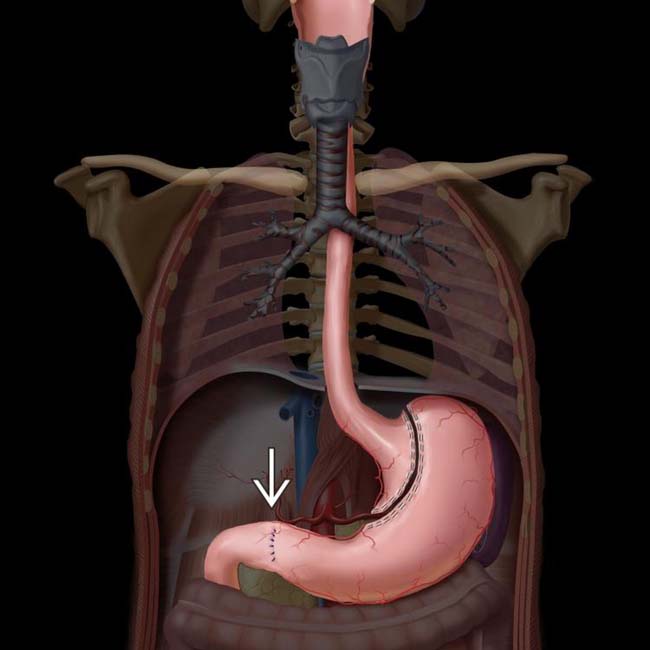

anastomosed to the cervical esophagus. Note the position of the gastric staple line

anastomosed to the cervical esophagus. Note the position of the gastric staple line  along the right side of the conduit.

along the right side of the conduit.

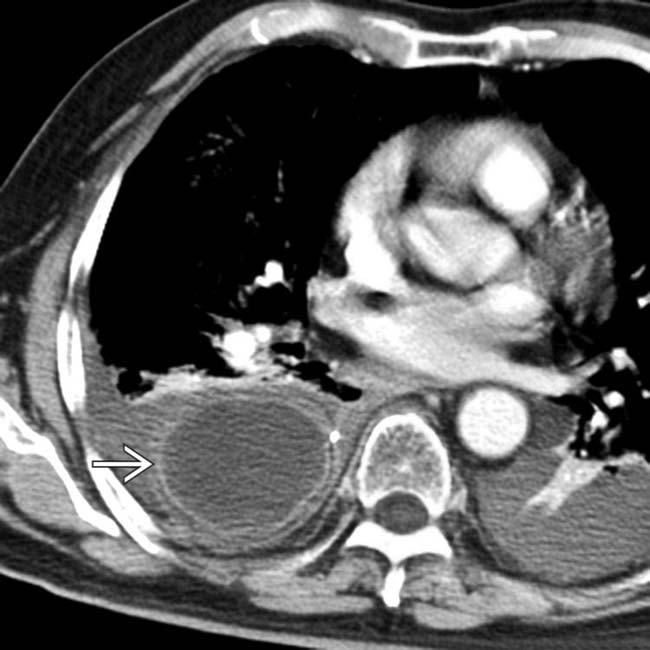

in the paravertebral location. Note the position of the gastric staple line

in the paravertebral location. Note the position of the gastric staple line  . The conduit is not filled with retained fluid, and there is no evidence of lung injury from reflux.

. The conduit is not filled with retained fluid, and there is no evidence of lung injury from reflux.IMAGING

Surgical Procedures

• Transthoracic esophagectomy

Usually performed through right intercostal approach (Ivor Lewis procedure)

Usually performed through right intercostal approach (Ivor Lewis procedure)

Many variations exist

Many variations exist

Usually performed through right intercostal approach (Ivor Lewis procedure)

Usually performed through right intercostal approach (Ivor Lewis procedure)

– Generally begins with laparotomy for mobilization of stomach, which is then used to create gastric tube/conduit that will replace resected esophagus

– Pyloroplasty or pyloromyotomy is performed to facilitate gastric emptying and to minimize gastroesophageal reflux

Many variations exist

Many variations exist

– e.g., left thoracotomy approach, transhiatal open approach (without thoracotomy), minimally invasive procedures (performed through ports in thorax and abdomen without open incision into either)

Complications

• Perioperative complications

Injury to recurrent laryngeal or vagus nerve (5-10%)

Injury to recurrent laryngeal or vagus nerve (5-10%)

Injury to recurrent laryngeal or vagus nerve (5-10%)

Injury to recurrent laryngeal or vagus nerve (5-10%)

• Postoperative complications

Essentially all patients have some degree of dysphagia, early satiety, and reflux following esophagectomy

Essentially all patients have some degree of dysphagia, early satiety, and reflux following esophagectomy

Anastomotic leak (10-16%)

Anastomotic leak (10-16%)

Delayed e mptying of conduit

Delayed e mptying of conduit

Essentially all patients have some degree of dysphagia, early satiety, and reflux following esophagectomy

Essentially all patients have some degree of dysphagia, early satiety, and reflux following esophagectomy

Anastomotic leak (10-16%)

Anastomotic leak (10-16%)

– Occurs more commonly with neck anastomoses, but thoracic anastomotic leaks cause more serious complications

Delayed e mptying of conduit

Delayed e mptying of conduit

– Mechanical obstruction

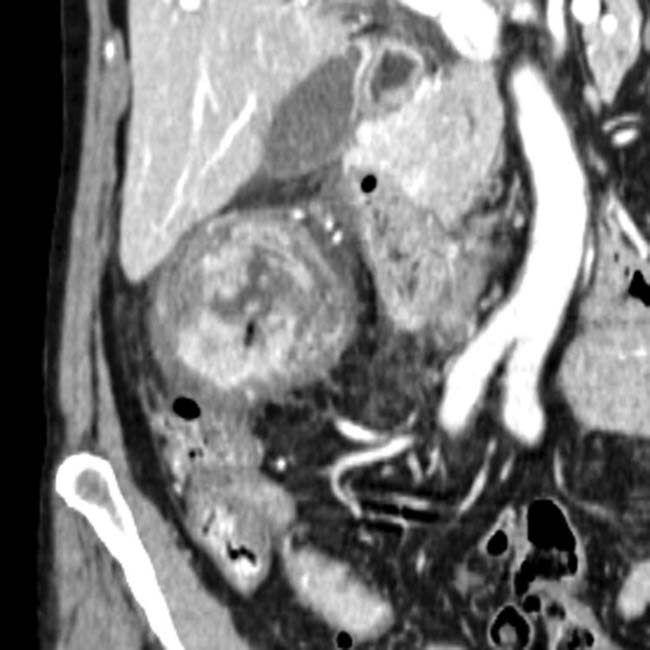

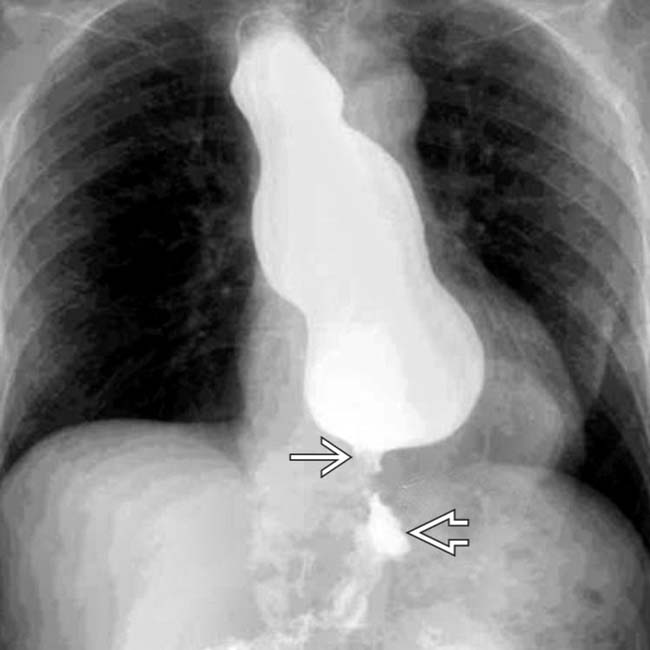

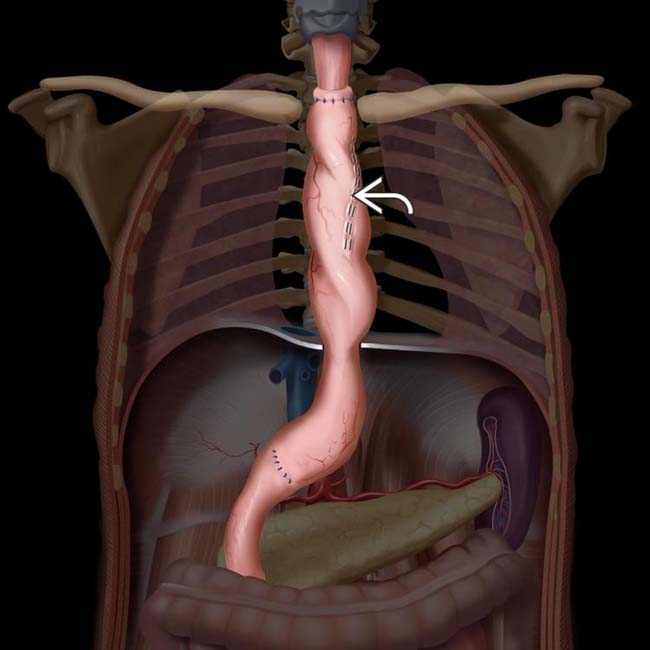

and evidence of severe aspiration pneumonia and pleural effusion. The conduit is probably twisted, as evidenced by the position of the gastric staple line

and evidence of severe aspiration pneumonia and pleural effusion. The conduit is probably twisted, as evidenced by the position of the gastric staple line  .

.

, as well as severe lung disease and pleural effusions.

, as well as severe lung disease and pleural effusions.

above the diaphragm

above the diaphragm  . The conduit is dilated with an air-fluid level, indicating partial obstruction. The conduit was pulled down into the abdomen at revision laparoscopy with resolution of symptoms.

. The conduit is dilated with an air-fluid level, indicating partial obstruction. The conduit was pulled down into the abdomen at revision laparoscopy with resolution of symptoms.

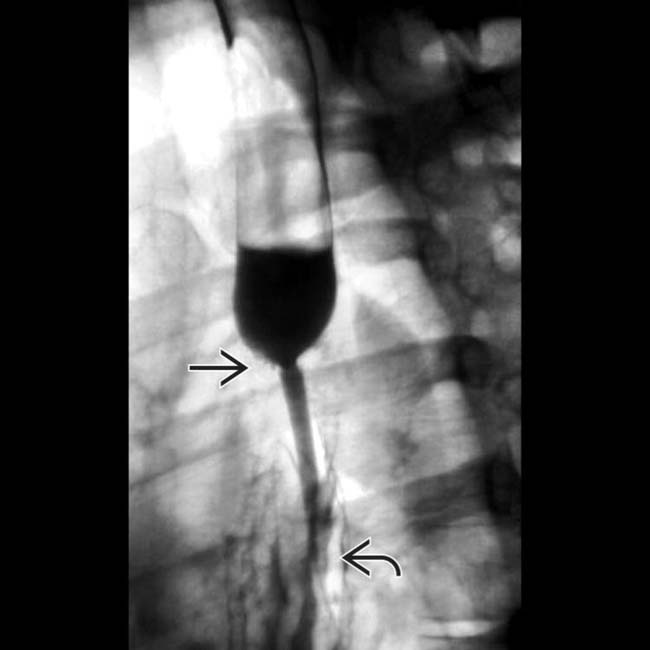

, not the pylorus, which has been widened by pyloroplasty

, not the pylorus, which has been widened by pyloroplasty  .

.

, which is proximal to the collapsed gastric antrum

, which is proximal to the collapsed gastric antrum  in this patient with mechanical obstruction of the conduit at the diaphragmatic hiatus (the most common site).

in this patient with mechanical obstruction of the conduit at the diaphragmatic hiatus (the most common site).

. The stomach is narrowed as it traverses the diaphragm

. The stomach is narrowed as it traverses the diaphragm  , but the pyloroplasty

, but the pyloroplasty  is neither the site nor the cause of the delayed emptying.

is neither the site nor the cause of the delayed emptying.

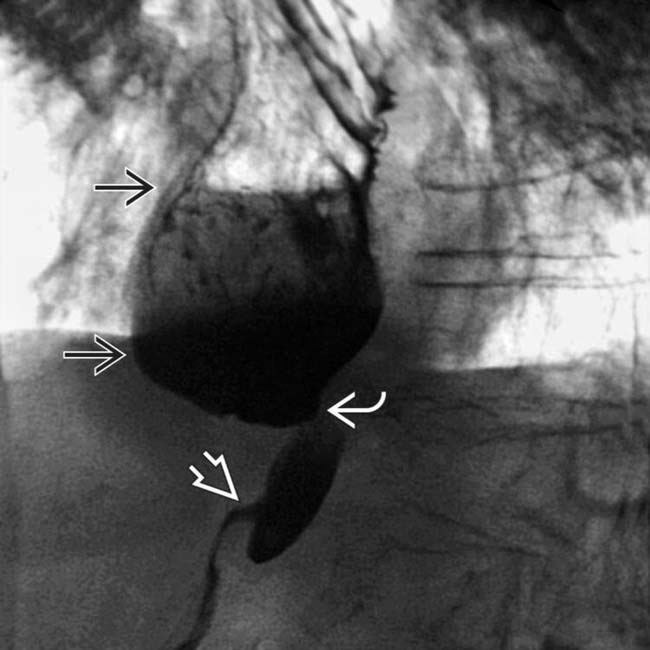

on upright film. Vagal nerve injury is the most common etiology.

on upright film. Vagal nerve injury is the most common etiology.

and omental fat posterior to the gastric conduit

and omental fat posterior to the gastric conduit  .

.

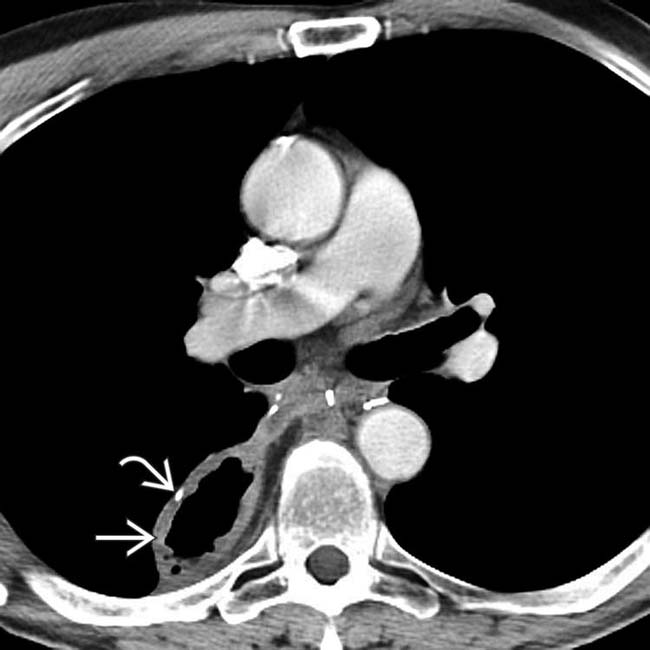

, which has rotated to the left anterolateral position.

, which has rotated to the left anterolateral position.

, suggesting impaired emptying. The position of the gastric staple line

, suggesting impaired emptying. The position of the gastric staple line  indicates rotation or volvulus of the conduit, as it is expected to be at the 9-o’ clock position

indicates rotation or volvulus of the conduit, as it is expected to be at the 9-o’ clock position

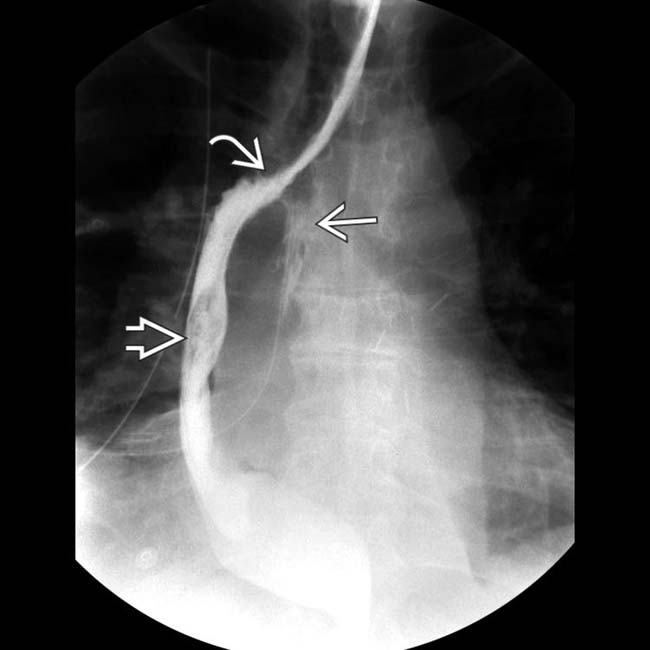

at the esophagogastric anastomosis with delayed emptying of the esophagus, evident as an air-fluid level. Note the smooth surface of the esophagus and the rugal fold pattern of the gastric conduit

at the esophagogastric anastomosis with delayed emptying of the esophagus, evident as an air-fluid level. Note the smooth surface of the esophagus and the rugal fold pattern of the gastric conduit  .

.

between the esophagus and the gastric conduit

between the esophagus and the gastric conduit  . There is an anastomotic leak

. There is an anastomotic leak  into the mediastinum.

into the mediastinum.

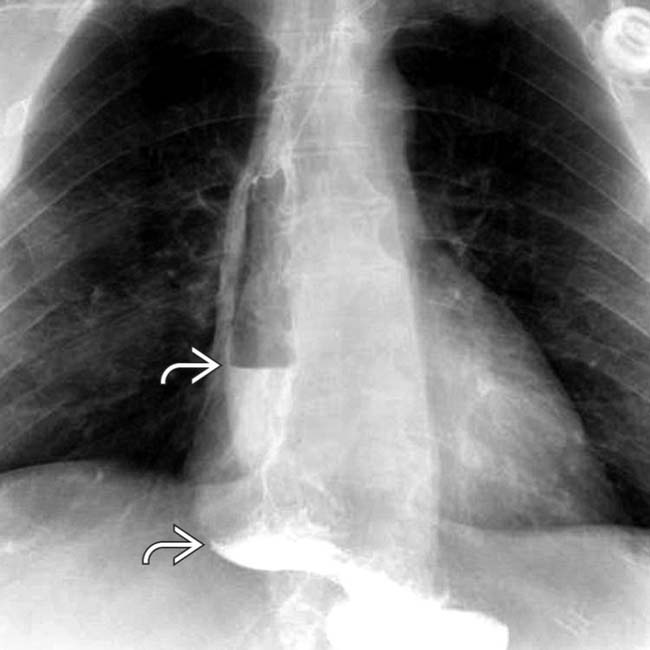

.

.

from the esophagogastric anastomosis

from the esophagogastric anastomosis  into the mediastinum.

into the mediastinum.

. There is a large soft tissue mass

. There is a large soft tissue mass  abutting the conduit and extending into the mediastinum in this patient with a recurrent tumor.

abutting the conduit and extending into the mediastinum in this patient with a recurrent tumor.

and the pyloroplasty

and the pyloroplasty  .

.

and extensive mediastinal mass effect

and extensive mediastinal mass effect  , representing recurrent esophageal tumor. A portion of the anastomotic staple line

, representing recurrent esophageal tumor. A portion of the anastomotic staple line  is seen.

is seen.