31 Esophageal Disorders

• Esophagitis is inflammation or infection of the esophagus and can be caused by reflux of gastric contents, infectious organisms, corrosive agents, or direct contact with swallowed pills.

• Candida species, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus are the most common organisms that infect the esophagus of an immunosuppressed patient.

• The most dangerous esophageal foreign body is a disc (button) battery, which can cause a chemically induced perforation in as little as 4 hours.

• Esophageal perforation may initially be manifested as nonspecific chest symptoms. The condition can rapidly progress to mediastinitis, overwhelming sepsis, and death.

• Esophageal motility disorders represent a heterogeneous group of conditions that result from derangement in peristalsis of the esophagus and abnormal functioning of the lower esophageal sphincter.

Reflux Esophagitis

Epidemiology

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) describes a constellation of symptoms or complications that result from reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. Even though approximately 40% of adults in the United States suffer from symptoms of heartburn at least once per month, the overall prevalence of GERD is just 14%.1,2 GERD represents a spectrum of disease from nonerosive to erosive esophagitis and finally Barrett esophagus.3 Common complications of GERD include esophageal strictures and the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Within the United States, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is increasing at an alarming rate of 4% to 10% per year.4

Pathophysiology

A number of conditions and lifestyle choices increase the risk for reflux esophagitis (Box 31.1). The primary pathophysiologic mechanism contributing to the development of GERD is an incompetent lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Inability of the LES to prevent reflux of stomach contents is influenced by esophageal anatomy, impaired gastrointestinal motility, acid hypersecretion, and increased abdominal pressure. Patients with a higher incidence of hiatal hernias, low LES pressure confirmed by manometry, and increased levels of reflux confirmed by esophageal pH monitoring have been shown to experience more severe GERD symptoms.5

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Heartburn is more severe when patients are supine, bend forward, wear tight clothing, or consume large meals. The pain may last from minutes to hours and may resolve spontaneously or with antacids. Patients with nocturnal symptoms often complain of “water brash,” which is the bitter, metallic taste of regurgitated gastric contents noted on arising from sleep. Approximately 80% of patients with GERD have primarily nocturnal symptoms that are exacerbated by being supine.6 Patients with daytime symptoms have postprandial heartburn and fullness even when upright. GERD can cause chronic cough, recurrent throat clearing, and wheezing as a result of aspiration of gastric contents from the esophagus into the trachea and larynx.7 A complaint of dysphagia in the setting of GERD is an ominous sign that should prompt endoscopic evaluation for underlying strictures or adenocarcinoma.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

GERD is a clinical diagnosis elicited by a detailed and directed history of the present illness. GERD should be diagnosed only after other life-threatening causes of chest pain have been convincingly excluded (Box 31.2). Providers must consider the potential life threats and serious medical conditions that can be manifested in a similar fashion to GERD. A thorough history is the most important consideration in the differentiation diagnosis of patients with GERD-like symptoms. The initial history should be obtained in concert with immediate electrocardiography. Physical examination, laboratory testing, and radiographic imaging aid only in the exclusion of alternative diagnoses. Cardiac stress testing may be required in certain patient populations. A reported clinical response to antacids should not be used to make the presumptive diagnosis of GERD in the emergency department (ED).

Treatment

Lifestyle modifications may reduce symptoms by decreasing the frequency and amount of gastric reflux. Examples of low-cost, low-risk recommendations are summarized in the Patient Teaching Tips box in this section of the chapter.8

H2RAs have similar efficacy with equivalent dosing schedules (Table 31.1). These agents have previously been recommended as first-line therapy; however, a Cochrane review suggests that PPIs relieve heartburn better than H2RAs do in patients treated without specific diagnostic testing.9 These medications should be used for 2 to 4 weeks before any reassessment of symptoms. Recurrence is a common problem in patients with reflux, and therefore many patients require long-term maintenance therapy.

Table 31.1 Equivalent Dosages for Histamine H2 Receptor Antagonists

| DRUG | RECOMMENDED DOSE |

|---|---|

| Cimetidine |

Success rates with PPIs approach 90%, and all agents have equal efficacy at appropriate doses (Table 31.2). Once-daily dosing before breakfast is sufficient for the control of mild to moderate GERD; twice-daily dosing should be considered for those with severe or refractory symptoms. Gastroprokinetic agents (cisapride) and coating agents (sucralfate) are less effective than PPIs but may be useful in selected patients as second-line agents.

Table 31.2 Equivalent Dosages for Proton Pump Inhibitors

| DRUG | RECOMMENDED DOSE |

|---|---|

| Omeprazole | |

| Lansoprazole | |

| Rabeprazole | |

| Pantoprazole | |

| Esomeprazole |

Next Steps in Care

Further diagnostic evaluation, including endoscopy, pH monitoring, manometry, and referral to a gastroenterologist, may be indicated for patients with persistent symptoms. Patients with known reflux esophagitis should be admitted to the hospital for suspected esophageal perforation, significant bleeding, obstruction, volume depletion, or intractable pain. Emergency upper endoscopy is indicated if life-threatening complications are suspected in patients demonstrating dysphagia, odynophagia, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, or weight loss.10

Infectious Esophagitis

Epidemiology

Infection of the esophageal mucosa, known as infectious esophagitis, may result from a variety of organisms in an immunocompromised host. Esophageal infections are more commonly observed in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cancer, neutropenia, or diabetes mellitus or in those taking chronic immunosuppressive medications, especially corticosteroids.11 Candida species are by far the most common cause of infectious esophagitis, although cytomegalovirus (CMV), varicella-zoster virus, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) represent common viral causes of the condition.12

Pathophysiology

Infectious esophagitis results from direct invasion of the infectious agent into esophageal tissue. Immunosuppression from any condition can lead to esophageal infections, although patients infected with advanced human immunodeficiency virus and those with lymphoma and leukemia receiving chemotherapy are at highest risk. Prevention of adherence of esophageal pathogens is an important pathophysiologic defense. Impairment of salivation, impairment of esophageal motility, and reduction in gastric acid production can result in opportunistic infections. Injury to the esophageal mucosa from radiation treatment also increases the risk for infection.12

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Pain or difficulty swallowing is the hallmark of infectious esophagitis; however, many infections may be asymptomatic or have other associated symptoms. Infectious esophagitis should be considered in immunocompromised patients at risk for opportunistic infections. Given the similar spectrum of signs and symptoms, the differential diagnosis of infectious esophagitis includes the same life threats and serious conditions as reflux esophagitis (see Box 31.2).

Pill Esophagitis And Caustic Esophageal Injury

Epidemiology

Pill esophagitis refers to damage to the esophageal mucosa by prolonged direct contact with a caustic agent. A variety of medications have been reported to cause esophageal injury, but the majority of cases involve potassium chloride, quinidine, emepronium bromide (Cetiprin), alendronate sodium (Fosamax), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, vitamin supplements, or antibiotics.13 Caustic injury to the esophagus results from the accidental or intentional ingestion of extremely acidic or alkaline agents. Caustic injuries are reported to have an estimated incidence of approximately 10,000 cases per year in the United States.14

Pathophysiology

Bisphosphonates, a notorious cause of pill esophagitis, cause esophageal injury as a result of nonspecific irritation secondary to contact between the pill and the esophageal mucosa.13 Following ingestion of a caustic substance, the extent of tissue injury and destruction depends on the physical properties and concentration of the ingested agent, the duration of contact, and the amount ingested.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

A presumptive diagnosis of pill esophagitis or caustic ingestion can be made when the history and the signs and symptoms are clear. For confusing or atypical findings, the same differential diagnosis for GERD listed in Box 31.2 must be investigated. If other esophageal disease is suspected (e.g., strictures, perforation), additional testing is indicated. Upper endoscopy is the most sensitive method of detecting pill-induced mucosal injury and assessing the extent of caustic injury following the ingestion of a corrosive agent. The timing of endoscopy is still under debate, but most medical centers perform the procedure early to define the extent of esophageal injury.13

Esophageal Foreign Bodies and Food Impaction

Epidemiology

Ingestion of a foreign body and food impaction are relatively common causes of ED visits. Esophageal foreign bodies are most commonly seen in children (80%) between 1 and 4 years of age.15 A significant proportion of adults with esophageal foreign bodies are prisoners, suffer from psychiatric illness, or have recurrent episodes of intentional foreign body ingestion. A wide range of ingested foreign bodies have been reported, and they can be conceptually grouped into the most threatening and most common foreign bodies (Box 31.3). The most dangerous esophageal foreign body in children is a disc (button) battery, which has shown a greater than sixfold increase in serious complication or fatalities from 1985 to 2009.16

Pathophysiology

Foreign objects tend to lodge in one of four areas of anatomic narrowing in the esophagus: the upper esophageal sphincter, the aortic crossover, the left mainstem bronchus crossover, and the LES. The upper sphincter is the most common site of impaction in children (75%), and the LES is the most common location in adults (70%).17 Foreign bodies in the upper esophageal sphincter may compress the airway and cause respiratory distress. Erosions from a foreign body or perforation from an ingested sharp object can result in mediastinitis and injury to adjacent structures such as the great vessels and trachea.

Although food impaction can occur in patients with a normal esophagus, both adult and pediatric patients often have an underlying esophageal abnormality. Abnormal areas of esophageal narrowing that predispose individuals to foreign body impaction include strictures, malignancies, dysmotility disorders (achalasia), and scleroderma.18,19

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Children and adults with esophageal foreign bodies may have an acute onset of drooling or respiratory distress. Other common symptoms associated with esophageal foreign bodies are retrosternal pain, dysphagia, coughing, gagging, wheezing, anorexia, and refusal to drink fluids. Unwitnessed ingestions account for approximately 40% of esophageal foreign bodies in children.20 Parental suspicion of an ingested object may prompt ED evaluation, even in an asymptomatic child. The vast majority of ingested objects will pass spontaneously; however, dangerous objects such as button batteries and sharp objects must be removed, even in asymptomatic patients.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Box 31.4 lists the differential diagnosis for esophageal foreign bodies. If a report of an ingested object is obtained from the patient, the diagnostic considerations are relatively straightforward. In both children and adults in whom a history of ingestion is unclear, more comprehensive assessment of the patient’s symptoms to include cardiac ischemia, infectious causes, and motility disorders should be considered. A high index of suspicion for an ingested foreign object must be maintained in children younger than 4 years because the history of ingestion is often absent and verbalization of symptoms is problematic.

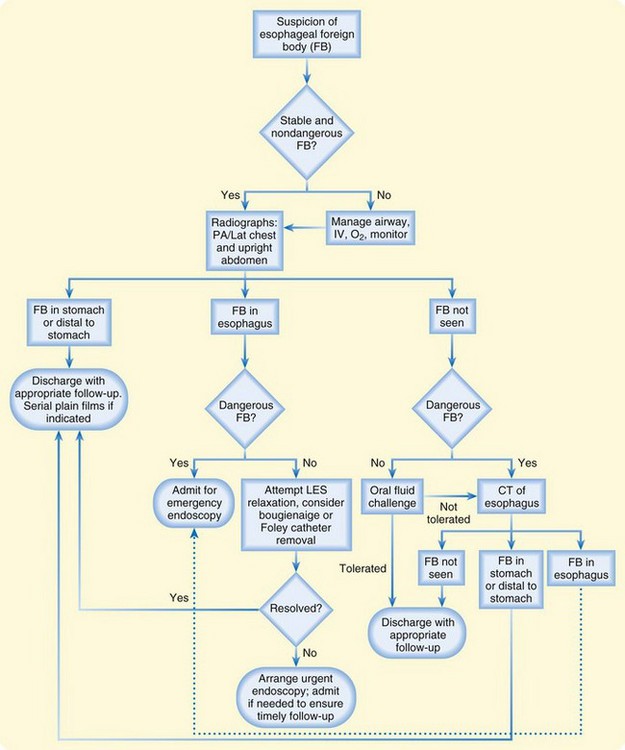

Treatment

A diagnostic algorithm for the evaluation of a suspected esophageal foreign body is presented in Figure 31.1. Foreign bodies found to be in the stomach will probably pass through the remainder of the gastrointestinal tract without intervention. Oral fluid challenges should be attempted when a foreign body is not identified on plain radiographs. Inability to tolerate fluids should prompt further evaluation with computed tomography or endoscopy.

Foreign bodies may also be guided into the stomach by bougienage, or advancement of a rubber dilator from the oropharynx into the esophagus. Removal of the foreign body may be attempted by passing a urinary catheter distal to the object under fluoroscopic guidance, inflating the balloon, and using the inflated distal catheter to withdraw the object. Foreign body advancement via bougienage and removal with a urinary catheter should be attempted only by skilled operators; complications include airway compromise and esophageal perforation. When reserved for relatively low-risk foreign bodies such as coins, these techniques have reported success rates of approximately 95% without serious complications.20 It should be recognized that removal of foreign bodies by bougienage is considered by many to be quite controversial.

Glucagon, nitroglycerin, and benzodiazepines have commonly been used to relax the LES and promote advancement of the foreign body in the esophagus. No convincing trials, however, have demonstrated that these medications improve the resolution of esophageal foreign bodies.21 Glucagon commonly causes vomiting, which poses an increased risk for aspiration. Use of these medications often serves only to delay involvement of a consultant for definitive removal of the foreign body. The addition of a gas-forming agent or oral meat tenderizer is also not recommended because of an increased risk for perforation.

Next Steps in Care

Patients with dangerous foreign bodies such as disc batteries and sharp objects should undergo emergency endoscopy. The opportunity for safe removal of an esophageal button battery is approximately 2 hours, with delay in diagnosis or removal of the battery contributing to catastrophic outcomes.16 Patients with unresolved but low-risk foreign bodies should be referred for endoscopy within 24 hours if they are able to tolerate oral fluids. Stable patients with nondangerous foreign bodies can be observed for several hours without harm.

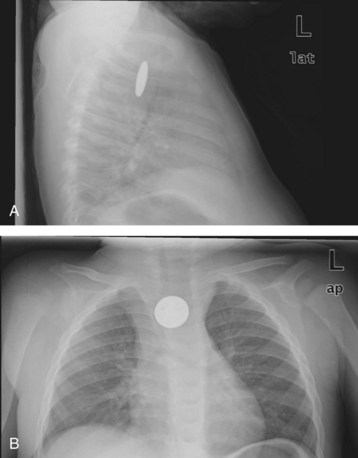

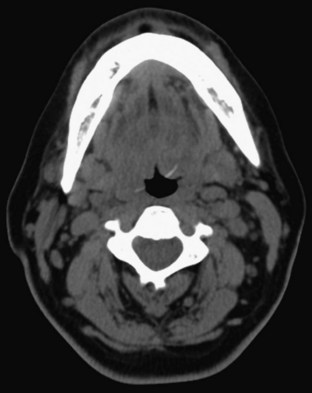

Adults with foreign bodies that resolve with observation should be referred for outpatient evaluation of potential structural or neuromuscular diseases of the esophagus. Children with resolved foreign bodies may be discharged for follow-up with a primary care provider. A swallowed coin in the esophagus (Fig. 31.2) and a fishbone in the hypopharynx (Fig. 31.3) are common esophageal foreign bodies.

Esophageal Perforation

Epidemiology

Esophageal perforation is defined as a transmural communication between the upper gastrointestinal tract and the mediastinum. Perforation leads to a rapidly progressive chemical and infectious mediastinitis that can result in sepsis and death. Iatrogenic perforations may occur at any anatomic location and account for up to 60% of all cases; they carry a mortality rate of approximately 20%.22

Boerhaave syndrome, or spontaneous esophageal perforation, is most commonly the result of forceful retching or vomiting. Other conditions associated with this syndrome are childbirth, coughing, seizures, asthma exacerbations, and the Valsalva maneuver. Even with treatment, this entity has a mortality rate approaching 30%.23

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Esophageal perforation is classically accompanied by mild, nonspecific symptoms that lead to misdiagnosis initially in more than half the patients. Pain is the initial symptom in 70% to 90% of cases, although variability in location makes this symptom difficult to interpret. Pain may be felt in the chest, neck, abdomen, or upper part of the back and may be increased with deep breathing or swallowing.24 Other common symptoms are dyspnea, odynophagia, vomiting, and hematemesis. The clinical findings depend on the location of the perforation and the delay between perforation and evaluation. Delayed evaluation for esophageal perforation will be complicated by findings of septic shock: fever, tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypotension. Physical examination may reveal subcutaneous emphysema of the neck or upper part of the chest in approximately 60% of patients. Hamman crunch is a classic but uncommon auscultatory finding attributed to mediastinal emphysema.

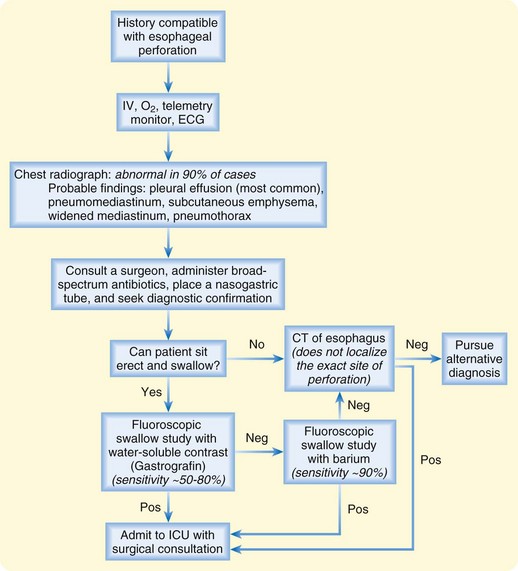

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

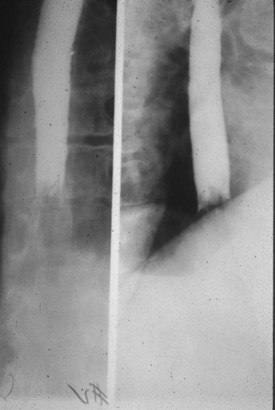

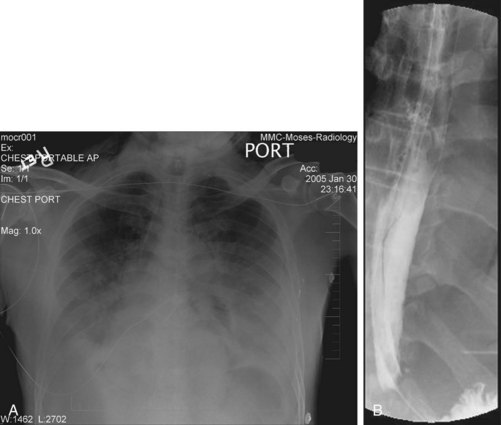

Given the variable findings in patients with esophageal perforation, misdiagnosis and delay in treatment are unfortunately typical. The initial symptoms, like many other esophageal disorders, can be consistent with myocardial infarction, peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, aortic dissection, and pneumothorax. A diagnostic algorithm for the evaluation of suspected esophageal perforation is presented in Figure 31.4. Chest radiographs often demonstrate nonspecific findings such as pleural effusions or perhaps pneumomediastinum. Contrast-enhanced fluoroscopic swallow studies should be performed in patients who can sit erect and tolerate liquids (Figs. 31.5 and 31.6). Computed tomography of the esophagus is an alternative method of confirming the presence but not necessarily the location of a suspected perforation (Fig. 31.7). Again, pleural effusions and pneumomediastinum are common findings.

Fig. 31.5 A and B, Chest radiographs demonstrating pneumomediastinum and bilateral pleural effusions.

(Courtesy of E. Wolf, MD, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY.)

Treatment

Severe sepsis can develop quickly in patients with esophageal perforation, especially those with a delayed diagnosis or evaluation. Aggressive resuscitation with early surgical consultation is mandatory. The ED practitioner should obtain intravenous access and administer broad-spectrum antibiotics effective against gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms. Acceptable empiric regimens include piperacillin/tazobactam (Zosyn), 3.375 g intravenously (IV), or ceftriaxone, 2 g IV, plus metronidazole (Flagyl), 500 mg IV, or clindamycin, 900 mg IV. A nasogastric tube should be inserted to decompress the stomach and reduce further mediastinal contamination (see also Chapter 46).

Early surgical intervention improves the odds of survival in patients with esophageal rupture, with the best results achieved if primary closure is performed within 24 hours. An increasing body of evidence suggests that esophageal stenting and nonoperative management may be useful in selected cases.25 In nonoperative management, drainage of pleural fluid collections with tube thoracostomy, continued nasogastric suction, and bypass of the esophagus with gastric tube placement or total parenteral nutrition are common adjunctive therapies.

Esophageal Motility Disorders

Epidemiology

Esophageal motility disorders represent a spectrum of disorders caused by abnormal coordination of peristalsis and relaxation of the esophageal sphincters. Effective characterization of these disorders has only recently been achieved after manometric and fluoroscopic measurements became more widely available. Five distinct disorders have been described: achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, nutcracker esophagus, ineffective esophageal motility, and disorders of LES relaxation.26 The best-defined esophageal motility disorder, achalasia, is rare with an incidence of 1 per 100,000 population.

Pathophysiology

Esophageal motility disorders result from a number of different pathophysiologic mechanisms that result in functional aberrations of the esophagus. Anatomically and radiographically, the esophagus usually appears normal. Achalasia results from degeneration of the plexus myentericus, which causes an impairment in relaxation of the LES and abnormal peristaltic contractions of the esophagus.27 The other motility disorders are less well understood and are believed to be caused by an impairment in the normally coordinated muscle contractions that occur with swallowing.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Esophageal motility disorders can be diagnosed only with manometric measurements of the esophagus. Emergency medicine physicians need to be aware that esophageal motility disorders exist and can be suspected clinically; however, they cannot be definitively diagnosed in the ED. Other life-threatening and serious causes of dysphagia, chest pain, and heartburn should be considered first. The same considerations for the broad differential diagnosis presented in Box 31.2 should be investigated.

Treatment

Therapies for esophageal motility disorders are as poorly defined as the disorders themselves. Treatment options for achalasia focus on reduction of LES pressure. Botulinum toxin injections, myotomy, and dilation of the LES have been use to treat achalasia with mixed success. Smooth muscle relaxant medications, such as calcium channel blockers, and benzodiazepines have also been used anecdotally to treat achalasia and other esophageal motility disorders without clear benefit.28

Kahrilas PJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1700–1707.

Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L, et al. Emerging battery-ingestion hazard: clinical implications. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1168–1177.

Pace F, Antinori S, Repici A. What is new in esophageal injury (infection, drug-induced, caustic, stricture, perforation)? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25:372–379.

Sepesi B, Raymond DP, Peters JH. Esophageal perforation: surgical, endoscopic, and medical management strategies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:379–383.

van Pinxteren B, Sigterman KE, Bonis P, et al. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux–like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11, 2010. CD002095

1 Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: results of the US Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:543–552.

2 Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, et al. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–1456.

3 Pace F, Pallotta S, Vakil N. Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a progressive disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:409–414.

4 Ofman J. Decision making in gastroesophageal reflux disease: what are the critical issues? Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:S67–S76.

5 Lord R, DeMeester SR, Peters JH, et al. Hiatal hernia, lower esophageal sphincter incompetence, and effectiveness of Nissen fundoplication in the spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:602–610.

6 Farup C, Kleinman L, Sloan S, et al. The impact of nocturnal symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:45–52.

7 Parsons JP, Mastronarde JG. Gastroesophageal reflux and asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16:60–63.

8 Kahrilas PJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1700–1707.

9 van Pinxteren B, Sigterman KE, Bonis P, et al. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux–like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11, 2010. CD002095

10 DeVault KR, Castell DO, American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190–200.

11 Baden LR, Maguire JH. Gastrointestinal infections in the immunocompromised host. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:639–670.

12 Mulhall BP, Wong RK. Infectious esophagitis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2003;6:55–70.

13 Pace F, Antinori S, Repici A. What is new in esophageal injury (infection, drug-induced, caustic, stricture, perforation)? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25:372–379.

14 Arevalo-Silva C, Eliashar R, Wohlgelernter J, et al. Ingestion of caustic substances: a 15 year experience. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1422–1426.

15 Chen MK, Beierle EA. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies. Pediatr Ann. 2001;30:736–742.

16 Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L, et al. Emerging battery-ingestion hazard: clinical implications. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1168–1177.

17 Stack LB, Munter DW. Foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14:493–521.

18 Prasad GA, Reddy JG, Boyd-Enders FT, et al. Predictors of recurrent esophageal food impaction. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:771–775.

19 Hurtado C, Furtura G, Kramer RE. Etiology of food impactions in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:43–46.

20 Arms JL, Mackenberg-Mohn MD, Bowen MV, et al. Safety and efficacy of a protocol using bougienage or endoscopy for the management of coins acutely lodged in the esophagus: a large case series. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:367–372.

21 Arora S, Galich P. Myth: glucagon is an effective first-line therapy for esophageal foreign body impaction. Can. J Emerg Med. 2009;11:169–171.

22 Chirica M, Champault X, Dray L, et al. Esophageal perforations. J Visceral Surg. 2010;147:e117–e128.

23 de Schipper JP, Pull ter Gunne AF, Oostvogel HJ, et al. Spontaneous rupture of the oesphagus: Boerhaave’s syndrome in 2008. Dig Surg. 2009;26:1–6.

24 Brinster CJ, Singhal S, Lee L, et al. Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1475–1483.

25 Sepesi B, Raymond DP, Peters JH. Esophageal perforation: surgical, endoscopic, and medical management strategies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:379–383.

26 Smout A. Advances in esophageal motor disorders. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:485–489.

27 Kahrilas PJ. Esophageal motility disorders: current concepts of pathogenesis and treatment. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14:221–231.

28 Richter JE. Achalasia: an update. J Neurogastroenterol. 2010;16:232–242.