8

Erythroderma

Introduction

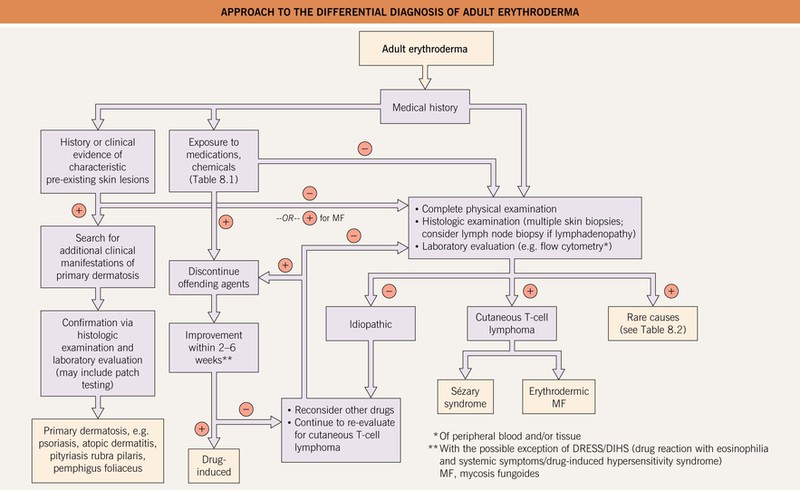

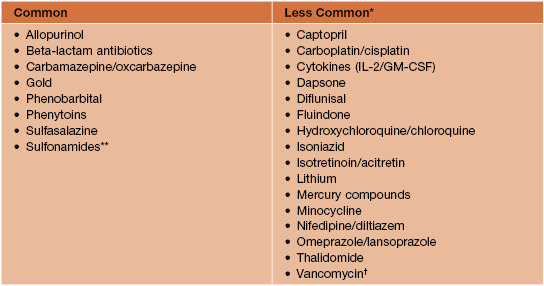

• A clinical presentation for a variety of diseases, often divided into three major categories: (1) primary skin disorders; (2) drug-related (Table 8.1); and (3) malignancies, particularly Sézary syndrome and erythrodermic mycosis fungoides.

Table 8.1

Drugs associated with erythroderma.

* Reference for additional drugs: Litt, JZ. 2010. Litt’s Drug Eruptions & Reactions Manual, 16th ed. London. Informa Healthcare.

** Includes furosemide.

† Not to be confused with red man syndrome due to rapid infusion of vancomycin.

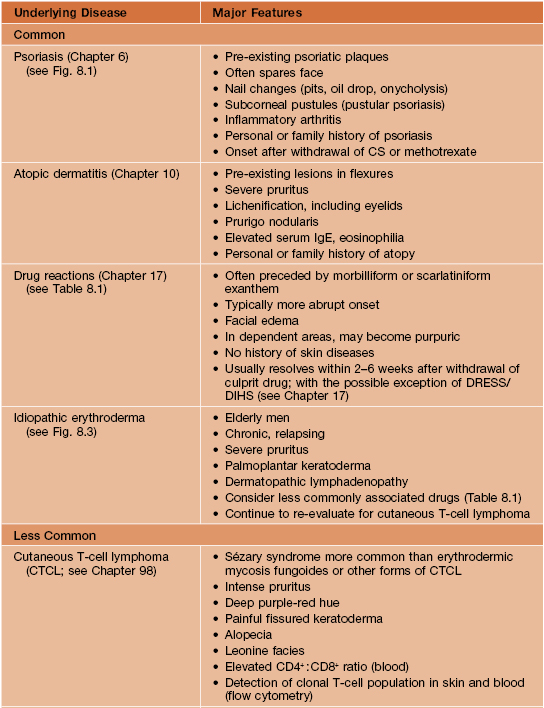

• In adults (Table 8.2), the most common primary skin disorders are psoriasis (Fig. 8.1) and atopic dermatitis, with allergic contact dermatitis or pityriasis rubra pilaris (Fig. 8.2) less common.

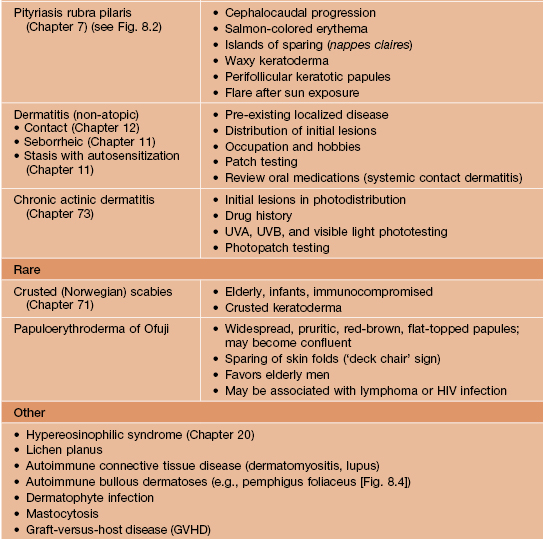

Table 8.2

Causes of erythroderma in adults.

DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (also referred to as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome [DIHS]).

Fig. 8.4 Erythroderma due to pemphigus foliaceus. Generalized erythema with widespread scale-crusts and large areas of erosion.

Fig. 8.1 Psoriatic erythroderma. A The disease flare correlated with the administration of lithium. B Nail findings (subungual hyperkeratosis, nail plate thickening, and oil-drop changes) point to the diagnosis of psoriasis. There is also soft tissue swelling of the forefinger due to psoriatic arthritis. A, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; B, Courtesy, Wolfram Sterry, MD.

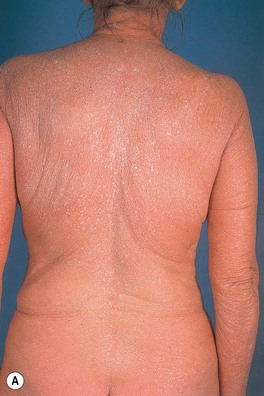

Fig. 8.2 Erythroderma secondary to pityriasis rubra pilaris. A few islands of sparing are noted on the upper back (A) but are more noticeable on the flank and breast (B). C Large thin scales are seen as well as the distinctive salmon to orange-red color.

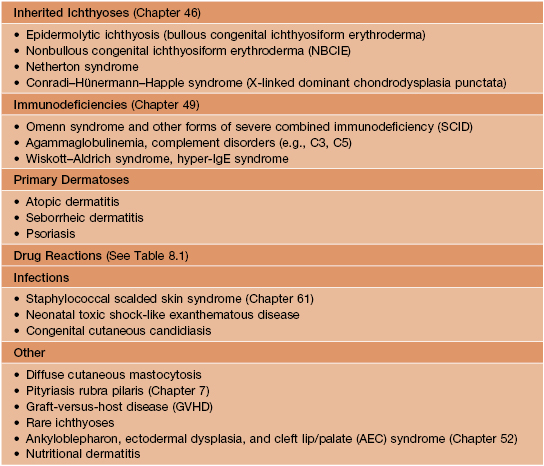

• In addition to atopic dermatitis, causes in infants and neonates (Table 8.3) include inherited ichthyoses, immunodeficiencies, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), and seborrheic dermatitis.

• Despite varied etiologies, patients have a number of clinical features in common: generalized erythema and desquamation (scaling) (Fig. 8.5), pruritus with secondary changes (e.g., lichenification), dyspigmentation, eruptive seborrheic keratoses (Fig. 8.6), secondary cutaneous infections, ectropion and purulent conjunctivitis; additional findings include palmoplantar keratoderma, nail dystrophy (Fig. 8.7), and alopecia.

Fig. 8.6 Eruptive seborrheic keratoses in a patient with idiopathic erythroderma. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 8.7 Nail dystrophy in a patient with idiopathic erythroderma. In addition to yellowing and thickening of the nail plate as well as subungual debris, splinter hemorrhages, and onycholysis, there is impending onychomadesis of at least one fingernail. Courtesy, Karynne O. Duncan, MD.

• In addition to these shared features, more specific clinical findings and initial sites of involvement may suggest the underlying etiology (see Table 8.2).

• Dx is often challenging because both clinical and histologic features may be nonspecific; repeat clinical examinations, laboratory evaluations, and skin biopsies are often necessary (Fig. 8.8).

• Despite a thorough evaluation, the cause can remain unknown (idiopathic) in up to a third of patients (see Fig. 8.3).

Fig. 8.3 Idiopathic erythroderma. This is the type of patient who requires longitudinal evaluation to exclude the development of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

• Some patients with idiopathic erythroderma eventually develop a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

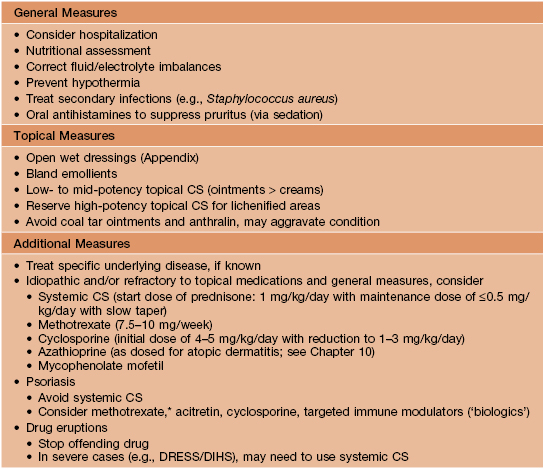

• Treatment strategies should address the dermatological symptoms, the underlying etiology, and the associated systemic complications (Table 8.4).

Table 8.4

General treatment strategies for adult erythroderma.

* May take 4–6 weeks to see any significant improvement.

DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (also referred to as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome [DIHS]).

• May represent a serious medical threat to the patient and require hospitalization.

For further information see Ch. 120. From Dermatology, Third Edition.