Epithelial Neoplasms of the Esophagus

Jonathan N. Glickman

Robert D. Odze

Introduction

Most benign and malignant neoplasms of the esophagus are epithelial in origin (Box 24.1). Overall, an estimated 17,000 new diagnoses of esophageal carcinoma, and 15,000 deaths, occurred in the United States in 2012.1 The incidence of esophageal carcinoma has increased dramatically in the United States in the past 30 years, principally because of a marked rise in Barrett’s esophagus (BE)-associated adenocarcinoma.2

Benign Neoplasms and Tumor-Like Lesions

Squamous Papilloma

Clinical Features

Esophageal squamous papilloma is the most common benign type of epithelial tumor of the esophagus.3,4 Studies suggest a prevalence rate of as much as 1%. These lesions may affect patients of all ages and both sexes. Most are asymptomatic, but large lesions may cause epigastric pain, dysphagia, or symptoms related to luminal obstruction.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of esophageal squamous papilloma is controversial. Whereas several studies have shown a high association (as much as 86%) with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection,3,4 other studies have failed to show a strong association with HPV.5 When detected, both low-risk and high-risk subtypes (e.g., types 6/11 and 16, respectively) have been reported. Variation in the prevalence of HPV among studies may result from differences in the techniques used to detect viral antigens or DNA and the possibility that as yet unidentified subtypes of HPV may be involved. Others have proposed that these lesions develop as a result of chronic mucosal irritation, perhaps secondary to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Pathologic Features

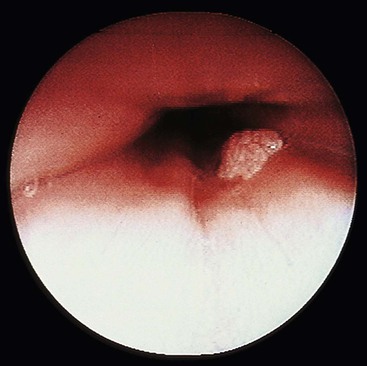

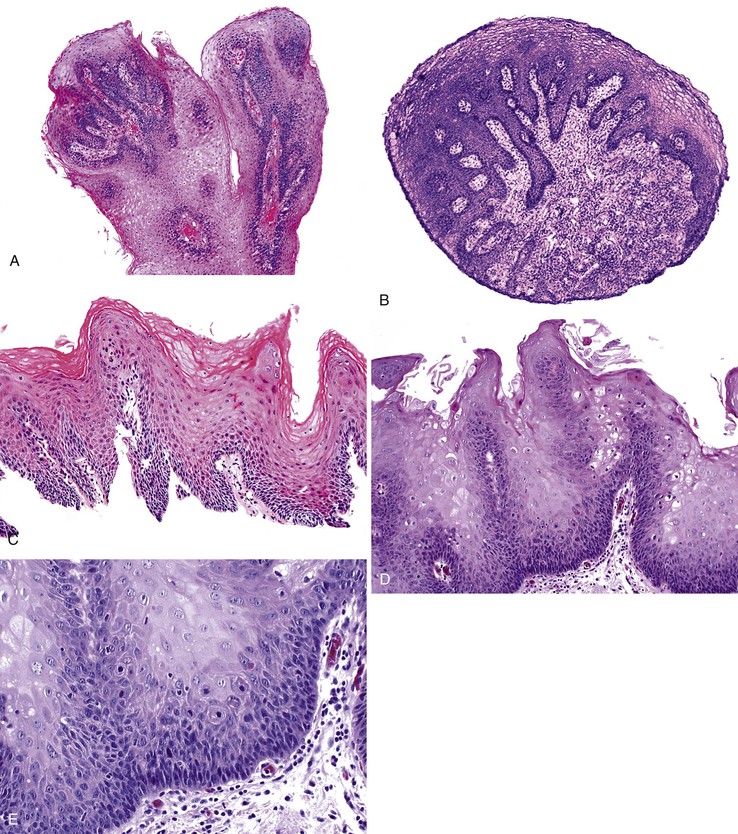

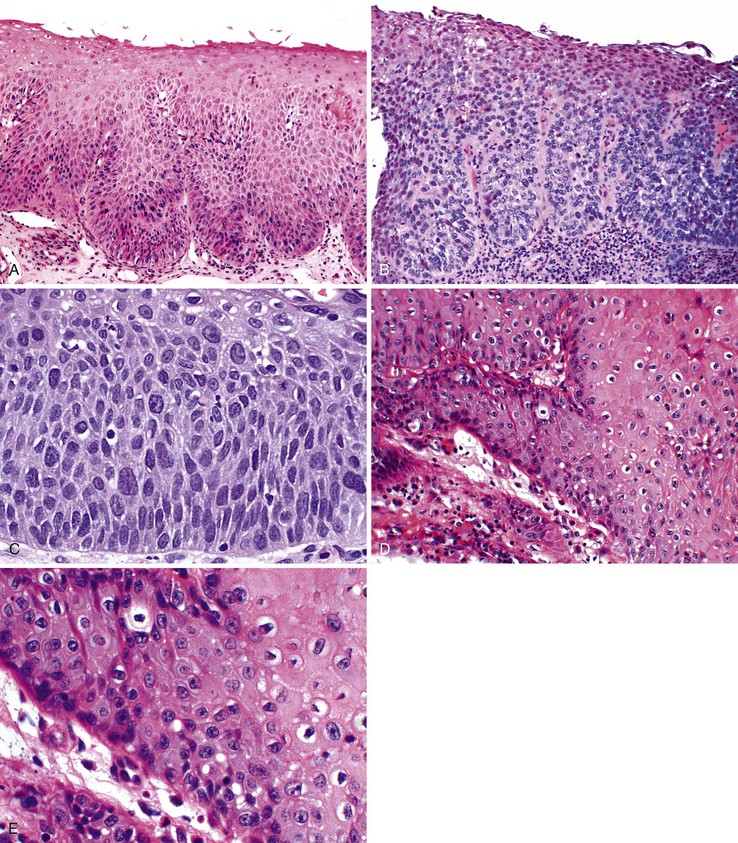

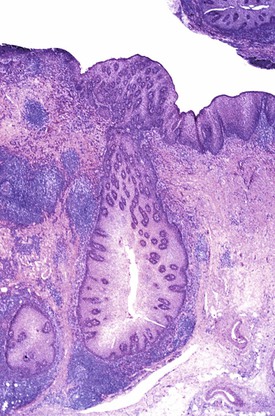

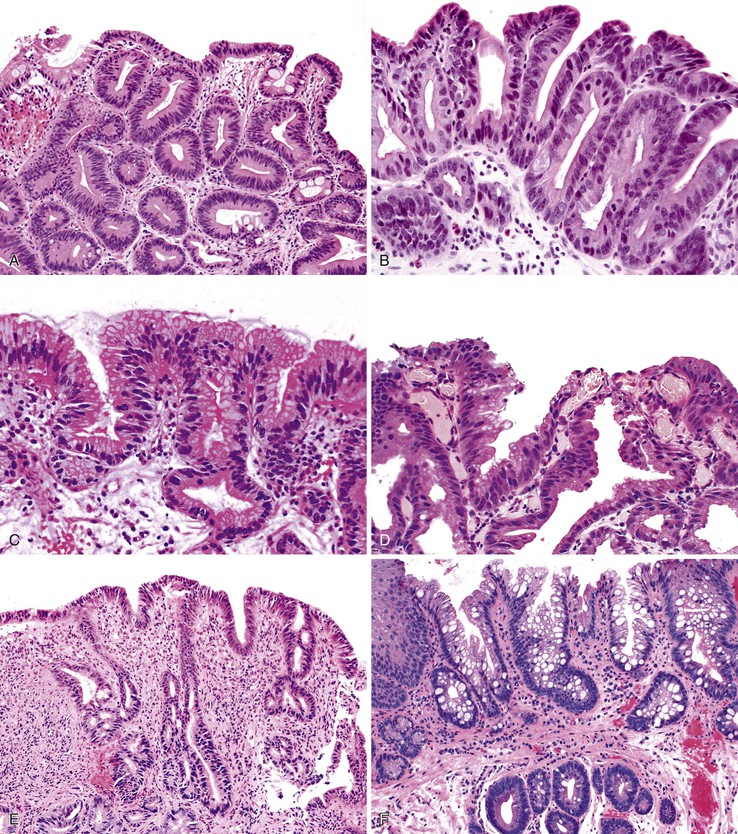

Grossly, esophageal squamous papillomas are usually small, discrete, sessile, soft, tan lesions that range in size from 0.5 to 3 cm; they occur most commonly in the distal or middle esophagus but may develop anywhere in the esophagus (Fig. 24.1). As much as 20% of cases are multiple, and rare cases of diffuse papillomatosis have also been reported.6,7 Microscopically, three distinct histopathologic types have been recognized: exophytic, endophytic, and spiked (verrucoid) (Fig. 24.2).3 The exophytic type, which is the most common, is composed of finger-like papillary fronds. The endophytic type shows a smooth, round surface contour and an inverted papillomatous proliferation. Least common is the spiked or verrucoid type, which has a spiked surface contour, a prominent granular cell layer, and marked hyperkeratosis.

All types are characterized by the presence of a branched fibrovascular core of lamina propria with a variable degree of acute and chronic inflammation and vascular congestion. The overlying squamous epithelium in all types is acanthotic, often reactive, showing a prominent basal cell zone and complete surface maturation (see Fig. 24.2, E). Features that are variably present include koilocytosis, parakeratosis, binucleation, dyskeratosis, and a prominent granular cell layer. Mitoses may be present in the basal and suprabasal epithelial layers, particularly in cases with active inflammation.

Differential Diagnosis

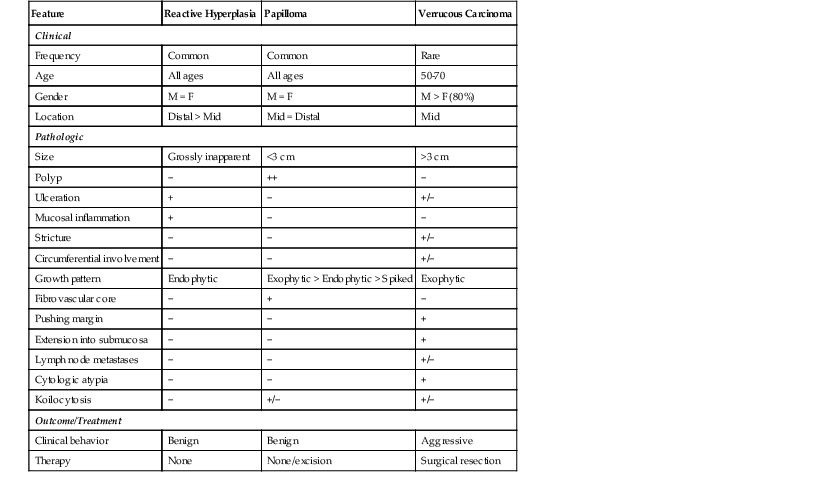

A papilloma that is large, is oriented poorly, or shows marked reactive changes may, on occasion, be difficult to distinguish from a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma or a verrucous carcinoma. However, esophageal squamous papillomas lack cytologic atypia, mitoses in the middle and upper levels of the squamous epithelium, atypical mitoses, and an infiltrative growth pattern characteristic of carcinoma. Furthermore, their gross (endoscopic) appearance is distinctive. In contrast to carcinoma, papillomas are well localized and well demarcated, smooth, discrete polyps without necrosis, stricture formation, or heaped-up borders. They lack the central keratinous crater characteristic of verrucous carcinoma (Table 24.1).

Table 24.1

Esophageal Squamous Papilloma: Differential Diagnosis

| Feature | Reactive Hyperplasia | Papilloma | Verrucous Carcinoma |

| Clinical | |||

| Frequency | Common | Common | Rare |

| Age | All ages | All ages | 50-70 |

| Gender | M = F | M = F | M > F (80%) |

| Location | Distal > Mid | Mid = Distal | Mid |

| Pathologic | |||

| Size | Grossly inapparent | <3 cm | >3 cm |

| Polyp | − | ++ | − |

| Ulceration | + | − | +/− |

| Mucosal inflammation | + | − | − |

| Stricture | − | − | +/− |

| Circumferential involvement | − | − | +/− |

| Growth pattern | Endophytic | Exophytic > Endophytic > Spiked | Exophytic |

| Fibrovascular core | − | + | − |

| Pushing margin | − | − | + |

| Extension into submucosa | − | − | + |

| Lymph node metastases | − | − | +/− |

| Cytologic atypia | − | − | + |

| Koilocytosis | − | +/− | +/− |

| Outcome/Treatment | |||

| Clinical behavior | Benign | Benign | Aggressive |

| Therapy | None | None/excision | Surgical resection |

+, Consistently present; ++, key feature; −, not present.

Papillomas may also be confused with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia occurring adjacent to a healing ulcer or overlying a granular cell tumor. However, the latter type of lesion lacks a fibrovascular core and other features of HPV infection such as koilocytosis. Unlike esophageal squamous papillomas, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia often shows abundant inflammation and surface erosion.

Adenoma

Adenomas of the esophagus may develop from the submucosal gland/duct system or, more commonly, from metaplastic columnar epithelium in cases of BE, in which case the term polypoid dysplasia is preferred.

Submucosal Gland/Duct Adenoma

Adenomas that develop from the submucosal glands are rare. They are usually histologically similar to those that arise from the minor salivary glands. This is not surprising because, embryologically, the esophageal submucosal glands are considered a continuation of the minor salivary glands of the oropharynx. They are usually submucosal and develop as well-circumscribed lesions that resemble pleomorphic adenomas9 or, more rarely, pancreatic or ovary-like serous cystadenomas.10

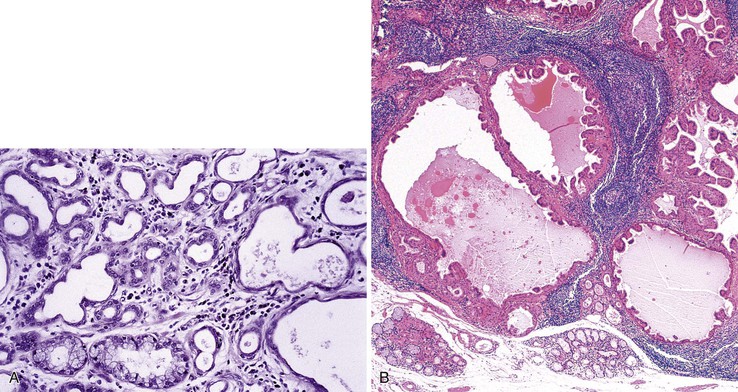

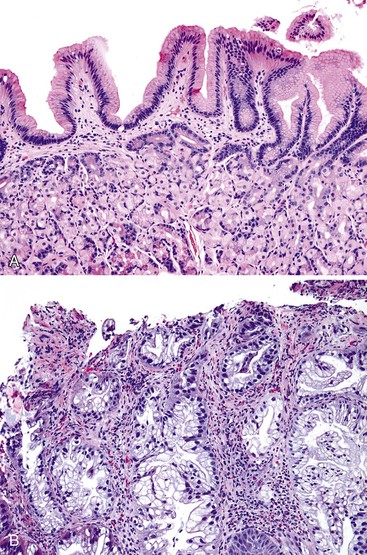

Microscopically, adenomas that develop from the submucosal gland ducts show a mixture of tubal, cystic, and papillary growth patterns similar to intraductal papillomas of the breast or sialadenoma papilliferum of the salivary glands.11 The epithelium typically contains two cell layers (similar to the normal submucosal gland ducts) with only mild to moderate cytologic atypia and infrequent mitoses (Fig. 24.3, A). Other adenomas may resemble salivary gland Warthin tumors (see Fig. 24.3, B). The immunophenotype of the tumor cells is also similar to that of the normal esophageal gland ducts.12 A mixed inflammatory infiltrate may be present as well. Most of these tumors behave in a benign fashion,13 although rare carcinomas have been reported.14

Polypoid Dysplasia in Barrett’s Esophagus

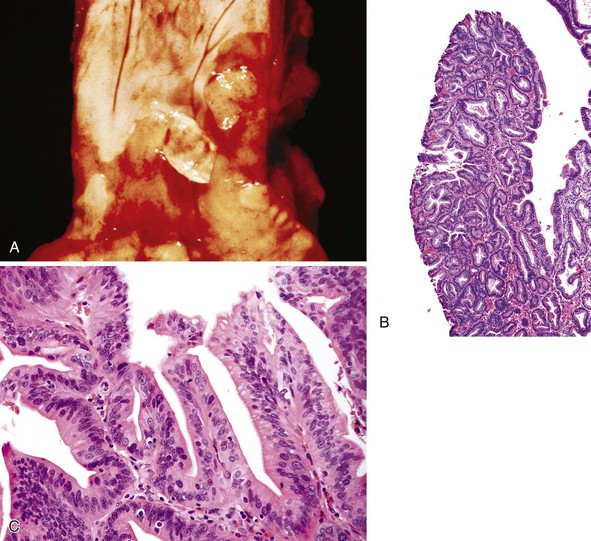

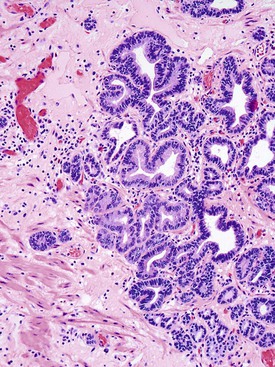

Adenoma-like polypoid dysplastic lesions may develop in BE (see Chapter 14). Endoscopically, these lesions usually appear as well-defined sessile or pedunculated polyps that range in size from 0.5 to 1.5 cm and usually occur in the middle or distal esophagus within areas of BE (Fig. 24.4). Histologically, these polyps are composed of a tubular or tubulovillous proliferation of low- or high-grade dysplastic epithelium, similar in appearance to colonic adenomas. The polyp epithelium is usually of the intestinal type, similar to the surrounding BE, but it may also show a gastric (foveolar) phenotype or mixed features of both.15

In one study, these lesions showed proliferative and molecular abnormalities (loss of heterozygosity of APC and TP53) similar to those of flat dysplasia and probably should be treated in a similar fashion.16 In fact, of the 10 cases reported, 9 were associated with adenocarcinoma, illustrating their high malignant potential.16 Because of the high association with flat dysplasia in the nonpolypoid Barrett’s mucosa, treatment by polypectomy is not considered adequate. Affected patients should be treated according to standard protocols for flat Barrett’s dysplasia, taking into account the extent, location, and grade of dysplasia in the esophagus as a whole.

Tumor-Like Lesions

Developmental Cysts and Duplications

Congenital cystic lesions and duplications may occur in the esophagus and mimic a malignant tumor because of their mass effect. These lesions, which are discussed more thoroughly in Chapter 8, are categorized by their site of origin, their embryologic derivation, and the histologic appearance of their lining epithelium. Clinically, they may be asymptomatic, or they may cause symptomatic compression of nearby respiratory or alimentary tract structures.

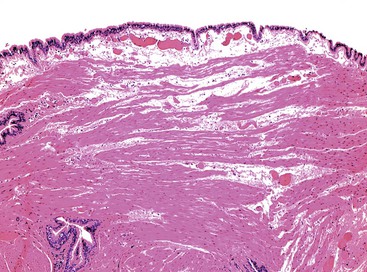

Bronchogenic cysts result from anomalous budding of bronchial structures derived from the embryonic foregut. They are typically located in the mediastinum or in the wall of the esophagus.17 Grossly, these cysts are usually unilocular and do not normally communicate with the esophageal lumen. Microscopically, they are lined by ciliated columnar epithelium and frequently contain cartilage, smooth muscle, and mucous glands in the surrounding cyst-lining tissue (Fig. 24.5).

Intramural cysts most likely develop as a result of abnormal recanalization of the esophageal lumen during embryogenesis. They may produce extrinsic compression and obstruction of the esophageal lumen or trachea, and they have also been associated with hemoptysis. Histologically, unilocular cysts may be lined by respiratory, gastric, oxyntic, squamous, or simple cuboidal epithelium, often with smooth muscle and ganglia in the cyst wall.18,19 A lymphoepithelial cyst of the cervical esophagus has also been reported.20 This lesion is characterized by a cyst lined most often by squamous or cuboidal epithelium and surrounded, uniformly, by a dense mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate.

Dorsal enteric (neurenteric) cysts occur primarily in the posterior mediastinum of infants and are thought to arise from incomplete closure of the notochordal remnant.21 These cysts may be associated with additional congenital defects, including spina bifida and vertebral anomalies. Microscopically, they are lined by gastric, intestinal, squamous, or respiratory epithelium and are usually surrounded by all the normal tissue layers of the bowel wall.

Other rare congenital anomalies include esophageal duplications, which may be asymptomatic but more often cause dysphagia or respiratory symptoms. They are usually isolated but may also be associated with other congenital foregut lesions such as pulmonary cystic malformations.22 Histologically, these cysts may be lined by squamous, gastric, ciliated columnar, or even pancreatic epithelium. The wall consists of admixed fibrous tissue and smooth muscle but does not contain organized layers of muscularis or cartilage.

Developmental cysts and duplications are benign. However, they may become infected as a result of rupture.23 Extremely rarely, adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma may develop from these lesions.24,25

Among acquired cystic lesions, mucoceles are not uncommon. They may even develop in excluded segments of esophagus created after surgery for esophageal atresia or rupture.26 In large or chronic cases, the cystic lining may not be apparent microscopically, revealing only inflammation and fibrous tissue.

Heterotopias

Gastric, thyroid, parathyroid, pancreatic, or even sebaceous tissue may be present as heterotopias in the esophagus. These deposits are presumed to be congenital in origin, although, as discussed later, some possible relationships with clinical conditions such as GERD and BE have been proposed.

Gastric heterotopia (“inlet patch”) is by far the most common type, being present in an estimated 2% to 11% of the general population.27–29 These lesions are usually located in the upper third of the esophagus. Although they are often asymptomatic, they may give rise to symptoms that result from complications of acid secretion, such as heartburn, dysphagia, active esophagitis, ulceration, bleeding, stricture, and perforation. Patients with Helicobacter pylori gastritis frequently show concurrent colonization of the heterotopic mucosa.30 The diagnosis is established by finding gastric glandular and surface epithelium (usually with parietal cells) in the esophagus in patients without intervening BE (Fig. 24.6, A). Some investigators have found a positive correlation with the presence of BE, although the basis for this association, if any, is unknown.27,29 Rarely, adenocarcinoma may develop in gastric heterotopia (see Fig. 24.6, B),31,32 and an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm arising from a pancreatic heterotopia has been reported.33

Heterotopic sebaceous glands are the second most common form of heterotopia in the esophagus. They may occur at any level of the esophagus, are frequently multiple, and usually appear as slightly elevated, yellowish lesions, 1 to 2 mm in diameter.34 Microscopically, these lesions show sebaceous cells within the epithelium or in the lamina propria (Fig. 24.7). Sebaceous cells are microvesicular and contain vacuolated cytoplasm filled with lipid substances. An excretory duct, with or without a connection to the surface epithelium, may be present as well. One study suggested that sebaceous glands may represent a metaplastic process because of their frequent association with reflux esophagitis and expression of cytokeratin 14 (CK14), which has been demonstrated in cell lines to represent the progeny of dormant stem cells.35

Pseudoepitheliomatous Hyperplasia

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia is a morphologic pattern of reactive squamous epithelium that most commonly occurs adjacent to healing ulcers. It is characterized by parallel, elongated, and typically evenly spaced and uniform columns (pegs) of highly reactive squamous cells with prominent nucleoli and mitoses, which may extend deep into the lamina propria (Fig. 24.8). Inflammation, both acute and chronic, is usually present, and this assists in recognizing the reactive nature of the cell proliferation. Lack of surface maturation (nucleated cells at surface) and parakeratosis may be present as well. Its appearance may simulate invasive squamous cell carcinoma, although the lack of either cytologic atypia or deeply infiltrative growth supports its benign nature.36 Furthermore, the squamous cells in reactive hyperplasia usually retain their polarity with respect to each other (absence of overlapping nuclei) and with respect to the basement membrane. Nevertheless, if the columns (pegs) of squamous epithelium are irregular and nonuniform, particularly in areas immediately adjacent to ulcers, and this feature is present in abundance, suspicion for a malignant process should be higher.

On occasion, this pseudoepitheliomatous reaction may be endoscopically visible and polypoid; some authors refer to these lesions as “hyperplastic” or “inflammatory” polyps.37 In addition, polypoid foci of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may be confused with the endophytic type of squamous papilloma. However, the latter lesions usually lack the significant inflammation and epithelial damage associated with hyperplasia.

Malignant Neoplasms

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical Features

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignant tumor of the esophagus worldwide. However, in the United States and Western Europe, the incidence of this type of esophageal cancer has been declining over the past 20 years, both in absolute terms and relative to esophageal adenocarcinoma (see later discussion). In 2005, the overall incidence of squamous cell carcinoma in the United States was approximately 2.0 per 100,000 person-years.38 It affects predominantly men (two to three times more often than women) with a peak incidence in the seventh decade of life. There is a marked geographic and ethnic variation in incidence: the highest rates (as many as 161 per 100,000) occur in China, Iran, South America, and South Africa.39 In the United States, the disease is approximately four times more common in black men than in white men.38 Common presenting symptoms include dysphagia and weight loss. In addition, as much as 3% of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma have concurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.40

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma is multifactorial and varies significantly among different regions of the world.41 Many cases develop without an identifiable cause or predisposing condition. Known risk factors in high-prevalence areas such as China and Iran include consumption of food or water rich in nitrates and nitrosamines, which results in the development of chronic esophagitis. Additional risk factors, common to both Western and developing countries, include tobacco smoke, alcohol, and various vitamin deficiencies. Other predisposing conditions are achalasia,42 Plummer-Vinson syndrome, strictures resulting from acid or lye ingestion, and the rare autosomal dominant condition tylosis palmaris et plantaris.43 Individuals related to affected family members are also at increased risk for esophageal carcinoma.

HPV infection has been implicated in tumorigenesis in many squamous epithelia. However, its precise role in esophageal carcinoma is controversial. HPV DNA has been isolated from esophageal tumors at prevalence rates of 0% to 66%.44–46 Viral types most commonly identified include HPV types 16 and 18. Varying rates of HPV positivity among studies may be attributed to differences in the techniques used to detect HPV and to different populations of patients studied (e.g., isolation rates are highest in high-risk areas such as China and Iran).45,46 Therefore, HPV is most likely a causative factor in only a small fraction of squamous cell carcinomas, and, when present, this agent is typically found in high-risk areas.

Molecular Features

At the molecular level, the most common alterations are overexpression of cell cycle regulatory proteins (e.g., cyclin D1 in 50% of tumors) and inactivation or loss of tumor suppressor proteins (e.g. p16 [CDKN2A] in as much as 80% of cases).47 Environmental risk factors such as tobacco, alcohol, and diet appear to produce mutations through the production of reactive oxygen species and DNA adducts. Polymorphisms in the ALDH2 and ALDH1B1 genes, which encode enzymes involved in alcohol metabolism, and in CYP1A1, a detoxification enzyme for xenobiotics, are associated with elevated risk for squamous cell carcinoma.48 Most of these tumors also express high levels of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), seen in 29% to 92% of the cases in some studies.47Some of these alterations, such as inactivating mutations of TP53 and increased cell proliferation, appear to occur early in neoplastic progression and are frequently detectable in squamous dysplastic precursor lesions as well.49 For more information on molecular features, refer to Chapter 23.

Squamous Dysplasia

Clinical Features

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, similar to its counterparts in the skin or cervix, is believed to develop through a progression of premalignant or dysplastic precursor lesions. Dysplasia is defined as the presence of unequivocal neoplastic cells confined to the epithelium. Squamous dysplasia is more common in patients at high risk for squamous cell carcinoma50 and is adjacent to squamous cell carcinomas in 60% to 90% of cases.51 In addition, dysplasia is frequently multifocal, and carcinomas associated with dysplasia are more likely to be multifocal in origin.52 Dysplasia is currently classified as low-grade or high-grade, based on the proportion of the thickness of the epithelium involved by dysplasia. In this two-tiered system, low-grade dysplasia roughly corresponds to the previously used terms mild and moderate dysplasia, and high-grade dysplasia includes severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ (see later discussion).

Pathologic Features

Gross Pathology

Dysplastic epithelium appears erythematous, friable, and irregular in more than 80% of cases.50 Erosions, plaques, and nodules may also be present. However, dysplasia may appear completely normal endoscopically. Mucosal staining with Lugol iodine may be helpful to highlight dysplastic mucosa and has been advocated as a means of improving the sensitivity of endoscopic biopsy surveillance in high-risk populations.53 When available, enhanced endoscopic visualization techniques such as narrow-band imaging are also helpful in highlighting dysplastic mucosa that is otherwise grossly nondescript.54 Dysplastic cells may also be harvested by exfoliative balloon cytology, a technique that is often used for screening in high-risk areas such as China (see Chapter 3).55

Microscopic Pathology

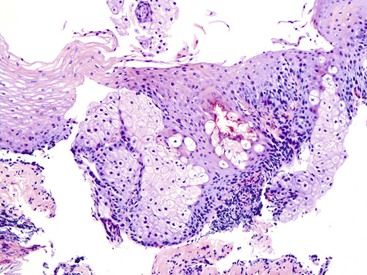

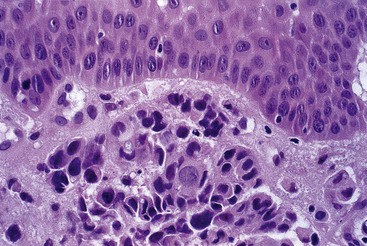

Dysplastic squamous epithelium is characterized by a combination of architectural and cytologic abnormalities that vary in extent and severity, and this is reflected in the grade (Fig. 24.9). The epithelium is usually hypertrophic but may be atrophic in rare circumstances. Dysplasia may involve the basal layer only or the full thickness of the epithelium. In 20% of cases, dysplastic epithelium spreads into esophageal mucosal gland ducts and simulates stromal invasion.56 Low-grade dysplasia reveals involvement of the basal third to half of the squamous epithelium with neoplastic cells, whereas high-grade lesions show complete or almost complete involvement of the native squamous epithelium. Dysplastic cells may occasionally grow as isolated cells in a horizontal pagetoid fashion, although this pattern must be distinguished from pagetoid involvement of the squamous epithelium by adenocarcinoma.57,58

Cytologic changes include nuclear hyperchromasia, pleomorphism, increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm (N : C) ratio, and increased mitotic rate. The chromatin of dysplastic cells is usually coarse and may be associated with thickening of the nuclear membrane. Nucleoli may be present but are not a consistent feature and are not specific because they are also frequently present in reactive squamous epithelium (discussed later). When present, nucleoli may be unusually large in size and irregular in shape. Architecturally, dysplastic cells display disorganization, loss of polarity, overlapping nuclei, and lack of surface maturation, which are key features in helping to distinguish true dysplasia from non-neoplastic (reactive) processes (see Fig. 24.9, C). Mitotic figures are usually increased in number and may be found at any level of the epithelium (base, midepithelium, or surface). Abnormal (tripolar or disorganized) mitotic figures may be present as well, particularly in high-grade lesions.

Rarely, precursor dysplastic lesions may reveal a proliferation of disorganized large cells (with a normal or even low N : C ratio) with open irregular nuclei, prominent enlarged and irregular single or multiple nucleoli, peripheral condensation of chromatin, and multinucleation (see Fig. 24.9, D and E). In these cases, the border between the epithelium and the lamina propria is often highly irregular, showing sharp, budding, or bulbous expansions of epithelium protruding deep into the lamina propria. This type of dysplastic epithelium is often associated with inflammation and surface maturation, although the latter to a much lesser degree than in either normal or reactive squamous epithelium. In these cases, distinguishing dysplastic epithelium from either markedly reactive squamous epithelium or very well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma may be extremely difficult. Often, repeat biopsies from deeper portions of the lesion and close correlation with the gross endoscopic appearance are necessary to help establish a final diagnosis. In these cases, invasion should not be diagnosed unless there is unequivocal evidence of irregular clusters of neoplastic cells within the deep lamina propria that are clearly disconnected from the overlying surface epithelium (on deeper levels of tissue sectioning) and associated with a peritumoral stromal desmoplastic response.

Differential Diagnosis (Reactive versus Neoplastic)

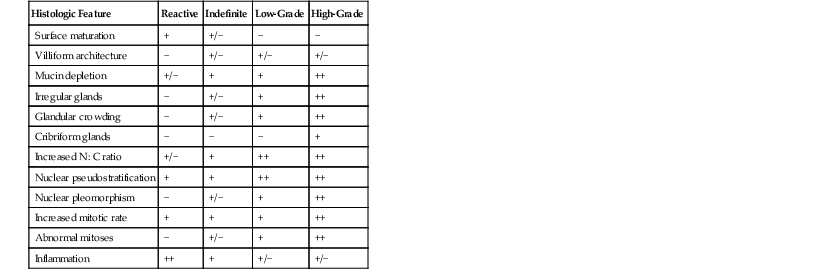

Squamous dysplasia must be distinguished from reactive epithelial changes associated with esophagitis. Although regenerating squamous cells may show mild nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, and expansion of the basal cell layers, they lack significant nuclear pleomorphism, overlapping nuclei, and nuclear crowding and do not display abnormal mitoses (see Fig. 24.9). Unlike in dysplasia, the chromatin is typically fine and homogeneous, and nucleoli, when present, are small and regular in shape. Architecturally, reactive squamous epithelium often displays some degree of surface maturation. Essential to the benign, non-neoplastic diagnosis is the fact that the basal and suprabasal layers maintain their polarity and orderly spacing in reactive lesions. Mucosal inflammation frequently accompanies reactive squamous epithelium, and in the presence of inflammation, a diagnosis of dysplasia should be rendered with caution. In biopsy specimens in which the epithelial changes appear sufficiently marked to suggest dysplasia but a reactive process cannot be excluded because of inflammation, a diagnosis of “indefinite for dysplasia” is appropriate. In such cases, follow-up biopsies after treatment of the underlying esophagitis frequently help resolve the diagnostic uncertainty. The results of ancillary stains, such as strong nuclear staining for TP53 (indicative of inactivating mutations) and extensive, suprabasal cell proliferation highlighted by the proliferation marker Ki67, may also support a diagnosis of dysplasia in problematic cases.49 Histologic features useful in the differential diagnosis of squamous dysplasia are summarized in Table 24.2.

Table 24.2

Reactive Hyperplasia versus Dysplastic Squamous Epithelium

| Feature | Reactive | Dysplastic |

| Clinical/Endoscopic | ||

| Esophageal SCC risk factors | +/− | + |

| Normal appearance | +/− | +/− |

| Erythema | +/− | +/− |

| Irregular/nodular | − | +/− |

| Abnormal Lugol/chromoendoscopy | − | + |

| Pathologic | ||

| Nuclear pleomorphism | − | ++ |

| Increased N : C ratio | +/− | ++ |

| Nuclear hyperchromasia | +/− | + |

| Increased mitotic rate | +/− | + |

| Abnormal mitoses | − | + |

| Nuclear crowding, disarray | − | ++ |

| Surface maturation | + | +/− |

| Inflammation | + | +/− |

| Immunohistochemical/Molecular | ||

| TP53 mutation/abnormal staining | − | + |

| Full-thickness Ki67 staining | − | + |

| DNA aneuploidy | − | + |

N : C ratio, Nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; +, consistently present; ++, key feature; −, not present.

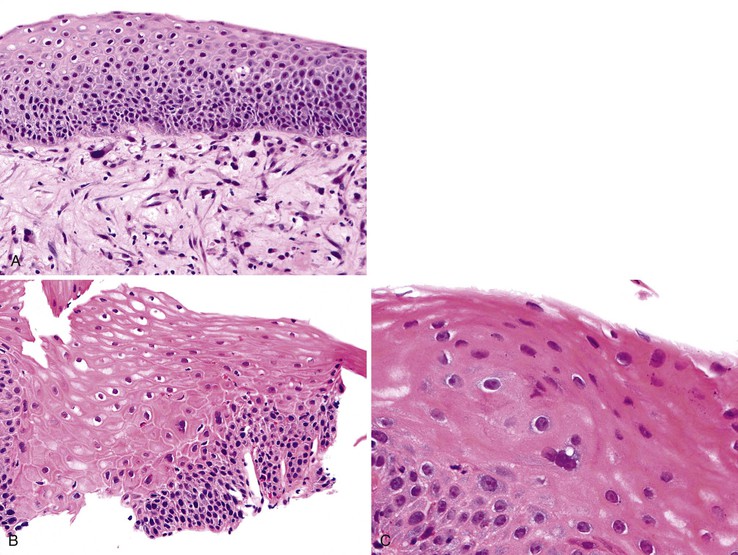

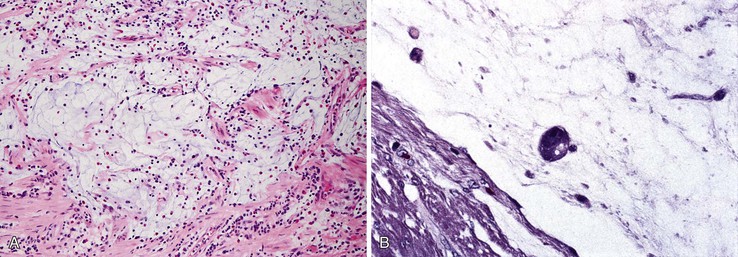

In biopsy specimens from patients who have received chemotherapy or radiotherapy, the squamous epithelium may contain markedly atypical cells with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei that raise the possibility of dysplasia. However, in contrast to dysplasia, these cells do not have an increased N : C ratio and often contain distinctive vacuolization in their cytoplasm. Furthermore, unlike in dysplasia, mesenchymal cells showing similar changes may also be present in the lamina propria, as well as other characteristic stromal changes of chemotherapy or radiotherapy (Fig. 24.10, A). Therefore, awareness of the patient’s clinical history is critical.

Biopsy specimens from patients with esophagitis caused by GERD or other causes such as drug effects occasionally contain multinucleated epithelial giant cells, raising the possibility of dysplasia (see Fig. 24.10, B and C).59 In these cases, no other cytologic or architectural features of dysplasia are present, and results of special studies for viral inclusions are negative. In inflammation-induced multinucleation, the nucleated squamous cells are typically basal or suprabasal in location and may be increased in number adjacent to areas of ulceration. In contrast, multinucleated virally infected cells (e.g., herpes simplex) are common in the surface epithelium and adjacent to sloughing epithelium.

Prognosis and Treatment

Squamous dysplasia frequently occurs adjacent to invasive carcinoma. For example, 30% of patients with a biopsy diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia show invasive squamous cell carcinoma in subsequent endoscopic resections.60 In addition, patients with squamous dysplasia are at increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma on follow-up. In a 13-year follow-up study of patients from China, 106 with low-grade dysplasia and 23 with high-grade dysplasia, those with low-grade dysplasia had a threefold to eightfold increased risk, and patients with high-grade dysplasia had a 28- to 34-fold increased risk for invasive carcinoma.61 In another study, 15% of patients with low-grade dysplasia progressed to high-grade dysplasia, whereas invasive carcinoma developed in 30% of patients with high-grade dysplasia during an 8-year follow-up period.62 However, dysplasia may also regress or disappear, although sampling error certainly may account for a normal finding on follow-up biopsy in a patient with dysplasia in a prior biopsy specimen. Therefore, patients with a diagnosis of squamous dysplasia require thorough endoscopic examination with biopsies, first to exclude synchronous invasive squamous cell carcinoma (particularly if associated with a visible mass lesion or ulceration) and second to detect the development of early invasive tumor on follow-up. Any grade of squamous dysplasia associated with a mass lesion should be considered carcinoma and treated accordingly. Low-grade dysplasia without a mass or associated carcinoma may be managed with repeated biopsies and continued surveillance in most instances. Some endoscopically subtle invasive carcinomas have been reported that apparently arose from low-grade dysplasia, further emphasizing the need for careful endoscopic scrutiny and adequate sampling in patients with any grade of squamous dysplasia.63

Endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection, which permits removal of dysplastic lesions or even early superficial cancers, aids in the diagnosis of early invasive tumors and is performed increasingly in some highly specialized centers. In one study of 87 patients with high-grade dysplasia and 213 patients with early (intramucosal) carcinoma treated with these two techniques, a total of 19 patients (6%) developed recurrences over an 85-month follow-up period. Endoscopic submucosal dissection gave superior results, with no nodal or distant metastases during a 36-month follow-up period.60

Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Box 24.2)

Squamous cell carcinomas may be separated into early (superficial) and late (advanced) types. Superficial squamous cell carcinomas are defined as tumors that invade the lamina propria and submucosa but do not penetrate the muscularis propria. These tumors constitute approximately 15% to 20% of all invasive squamous cell carcinomas, with higher prevalence rates in populations that routinely undergo endoscopic surveillance.39,51

Pathologic Features

Gross Pathology

Squamous cell carcinomas occur in the middle third of the esophagus in 50% to 60% of cases, the distal third in 30%, and the proximal third in 10% to 20%.39,64 Superficial tumors most commonly appear as mucosal plaques or slightly elevated flat lesions but may also be ulcerated, polypoid, or even grossly inconspicuous. Superficially invasive tumors are more commonly multicentric (as much as 20% of cases) when compared with advanced tumors. This finding may reflect either the presence of synchronous primary tumors occurring in a background of dysplasia or the presence of satellite tumor nodules resulting from intramural metastasis.52,65

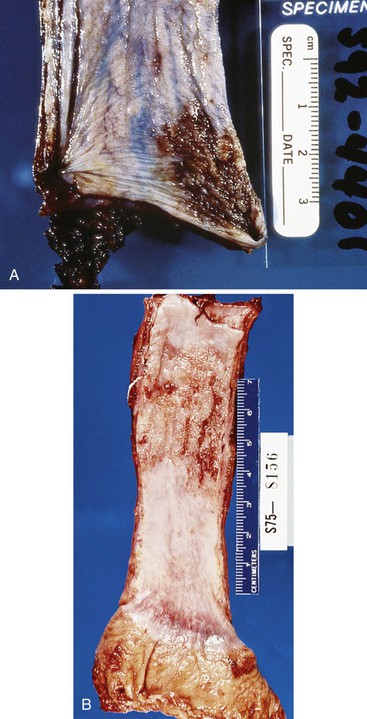

The gross appearance of advanced tumors may be classified as exophytic or fungating (60% of cases), ulcerating (25% of cases), or infiltrative (15% of cases) (Fig. 24.11).39 However, this feature is not a significant prognostic factor. In patients treated with preoperative irradiation or chemotherapy, the tumor may be invisible or perhaps replaced by a shallow surface erosion.

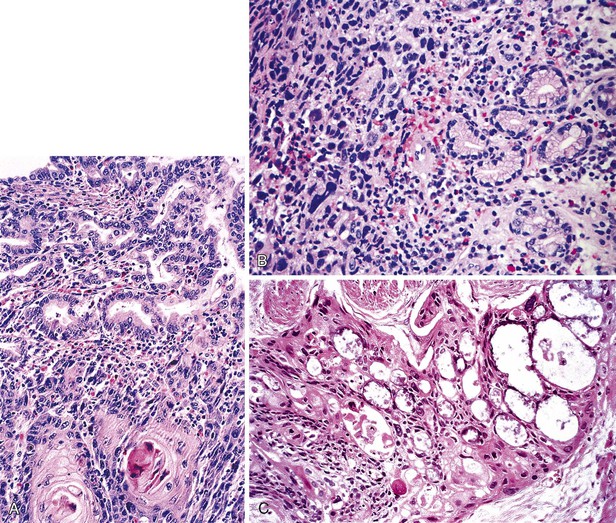

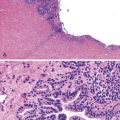

Microscopic Pathology

Superficially invasive tumors consist of irregular, elongated projections of dysplastic epithelium that extend into the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa as isolated cells or clusters of cells with a minimal desmoplastic response. Invasion of mucosal and submucosal lymphatics is not uncommon and is likely to account for the occasional instances of intramural metastasis. Advanced carcinomas spread through the esophageal wall, either with an infiltrative pattern composed of individual small nests of tumor cells or with an expansile (pushing) growth pattern composed of a solid mass of tumor cells with a smooth advancing edge. A prominent lymphocytic infiltrate occasionally surrounds the tumor.66

Squamous cell carcinomas show a range of differentiation from well to poor (Fig. 24.12). Well-differentiated tumors show variably sized nests of polygonal epithelioid cells with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm, easily recognizable intercellular bridges, and abundant keratinization (squamous pearls), with relatively few compact basaloid cells. Moderately differentiated tumors account for approximately two thirds of squamous cell carcinomas. They contain a higher proportion of primitive basaloid cells than well-differentiated tumors, and they are typically arranged in irregular nests and trabeculae with only focal keratinization. Poorly differentiated tumors show no evidence of keratinization, grow in solid sheets or as single cells, and may contain large, bizarre pleomorphic cells. Squamous cell carcinomas commonly show varying degrees of differentiation within a single tumor. Focal glandular or mucinous differentiation occurs in as much as 20% of cases.67,68 If the glandular and squamous components of the tumor are comparable in proportion but intimately mixed, it qualifies as an adenosquamous carcinoma (see Carcinoma with Mixed Squamous and Glandular Elements). Focal neuroendocrine or small cell differentiation has also been reported.69

Special studies are rarely required to establish a diagnosis of conventional squamous cell carcinoma but may be useful in small biopsy specimens or when rare tumor cells are present, such as for patients who have received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. By immunohistochemistry, squamous cell carcinoma cells are positive for broad-spectrum anticytokeratins and for cytokeratins 13, 14, 18, and 19.70,71 CK7 reactivity is present in as much as 29% of cases, but most cases are negative for both CK7 and CK20.72 In addition, most tumors express the nuclear antigen TP63, similar to squamous cell carcinomas that arise in other sites of the human body.49 Mucin stains may show focal positivity in a high proportion of cases, but this finding alone should not imply that the tumor is an adenosquamous carcinoma. Focal positivity for neuroendocrine markers, such as chromogranin and synaptophysin, also does not exclude a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma if it is present in a minority of the tumor cells and if the tumor is otherwise morphologically typical of a squamous cell carcinoma and does not show areas of small cell carcinoma.73

Differential Diagnosis

In small, poorly oriented biopsy specimens, distinguishing between in situ neoplasia (dysplasia) and invasive squamous cell carcinoma may be difficult. Squamous dysplasia, unlike invasive carcinoma, displays smooth-edged papillations with a continuous basement membrane and a connection to the surface epithelium and lacks single-cell infiltration, the presence of irregular discontinuous nests of cells, and desmoplastic stroma. However, the diagnostic criteria for squamous cell carcinoma differ between Western and Japanese pathologists, and many lesions that would be considered “high-grade dysplasia” by Western pathologists are diagnosed as “carcinoma” by Japanese pathologists solely on the basis of nuclear features.74

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma must also be distinguished from non-neoplastic lesions such as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and pseudodiverticulosis. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, similar to other reactive squamous proliferations, does not show significant nuclear pleomorphism, loss of polarity, or overlapping of nuclei and always reveals a connection to the surface epithelium (see Fig. 24.8). Reactive lesions do not show desmoplasia. Pseudodiverticulosis is a rare condition that produces numerous islands of reactive squamous epithelium in the mucosa and submucosa, some of which may be irregular in shape, simulating a carcinoma (Fig. 24.13).75 This condition is caused by extensive squamous metaplasia of the esophageal ducts and glands, which may occur in association with strictures or motility disturbances. On radiologic examination, pseudodiverticulosis may mimic carcinoma by showing irregular stricture formation. Identifying characteristic diverticula with a barium swallow procedure helps separate this condition from carcinoma radiologically. Pathologically, these lesions are distinguished from invasive carcinoma by the lack of an infiltrative growth pattern, absence of histologic features of dysplastic squamous epithelium, and the presence of smooth, often rounded, islands of reactive squamous epithelium associated with, or replacing, the submucosal glands and ducts with a prominent inflammatory infiltrate.

Biopsy or resection specimens from patients who have been treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy may contain only scattered atypical cells, which can occasionally make it difficult to distinguish residual carcinoma from reactive mesenchymal cells. Carcinoma cells may be identified by positive immunostaining for cytokeratins and an increased N : C ratio; reactive mesenchymal cells are typically cytokeratin negative and have expanded, often bubbly or “wispy” cytoplasm. Typically, the N : C ratio of these cells is maintained.

Poorly differentiated tumors may be difficult to recognize as squamous in phenotype, and melanoma or even lymphoma may be suspected on morphologic grounds. Positivity for cytokeratins and negativity for melanocytic and lymphoid markers may help eliminate these alternative diagnoses. In some patients, pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma involves the esophageal wall by metastasis or direct extension (see later discussion) and may be confused with a primary esophageal tumor. Adjacent squamous dysplasia provides strong evidence for an esophageal origin of the tumor. In addition, approximately 10% to 20% of lung squamous cell carcinomas show nuclear immunostaining for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), which is not expressed in esophageal epithelium or in tumors derived from it.76

Prognosis and Treatment

Squamous cell carcinomas may spread horizontally, but more typically they invade vertically through the esophageal wall and in this manner spread to involve contiguous organs such as the trachea, aorta, and pericardium. Intramural metastasis was detected in as much as 7% of resection specimens in one study.77 Regional lymph node metastasis is present in approximately 60% of patients at the time of diagnosis, and the lymph node positivity rate correlates with depth of invasion (<5% for intramucosal carcinomas and as much as 45% for submucosal carcinomas).64,78 Carcinomas originating in the upper thoracic esophagus are more likely to metastasize to cervical or upper mediastinal nodes, whereas tumors from the middle and lower thirds of the esophagus metastasize to lower mediastinal or perigastric nodes.39,64 However, skip nodal metastases are not uncommon in esophageal cancers. Distant metastasis, which most frequently involves the lung or liver, is present in as much as 60% of patients at autopsy.79

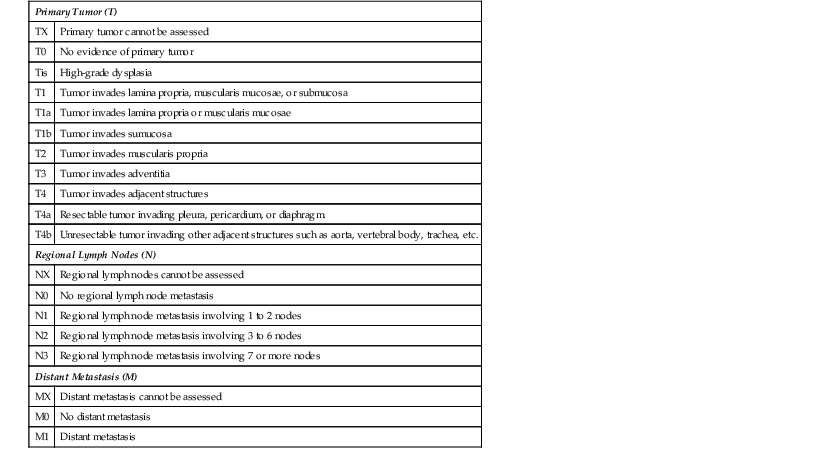

Overall, the 5-year survival rate for patients with squamous cell carcinoma is only 10%, but it approaches 30% to 40% for patients treated with esophagectomy.39,80,81 The most significant prognostic factor is tumor stage, which is based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification system (Table 24.3).81,82 Patients with tumors that penetrate into the submucosa have 5-year survival rates in the range of 60% to 75%, compared with 40% to 60% and 25% to 30% for patients with tumors that extend into the muscularis propria and the adventitia, respectively.81,83 The presence of lymph node metastasis and a greater number of positive lymph nodes are also correlated with worse prognosis.84 In patients who have received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, the presence of residual tumor is correlated with reduced survival. In one study of 175 patients, 55 (31%) had complete histologic tumor response; their median survival time was 125 months, compared with 21 months for those who had residual tumor.85 Some authors have also found that poor tumor differentiation is an independent prognostic factor,80,86 and tumor differentiation as well as tumor location are now incorporated into the AJCC staging for this tumor type (see Table 24.3). Intramural metastases77 and lymphovascular invasion87 have also been found to be predictive of regional lymph node metastasis and poor survival in some studies, but these findings need to be tested in a prospective manner.

Table 24.3

AJCC TNM Classification of Esophageal Carcinomas

| Primary Tumor (T) | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | High-grade dysplasia |

| T1 | Tumor invades lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa |

| T1a | Tumor invades lamina propria or muscularis mucosae |

| T1b | Tumor invades sumucosa |

| T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria |

| T3 | Tumor invades adventitia |

| T4 | Tumor invades adjacent structures |

| T4a | Resectable tumor invading pleura, pericardium, or diaphragm. |

| T4b | Unresectable tumor invading other adjacent structures such as aorta, vertebral body, trachea, etc. |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis involving 1 to 2 nodes |

| N2 | Regional lymph node metastasis involving 3 to 6 nodes |

| N3 | Regional lymph node metastasis involving 7 or more nodes |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

| Stage Grouping (Squamous Cell Carcinoma) | ||||||

| T | N | M | Grade | Location* | 5-Yr Survival (%) | |

| Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | 1, X | Any | 75 |

| Stage IA | T1 | N0 | M0 | 1, X | Any | 75 |

| Stage IB | T1 | N0 | M0 | 2-3 | Any | 60 |

| T2-3 | N0 | M0 | 1, X | Lower, X | ||

| Stage IIA | T2-3 | N0 | M0 | 1, X | Upper, middle | 53 |

| T2-3 | N0 | M0 | 2-3 | Lower, X | ||

| Stage IIB | T2-3 | N0 | M0 | 2-3 | Upper, middle | 41 |

| T1-2 | N1 | M0 | Any | Any | ||

| Stage IIIA | T1-2 | N2 | M0 | Any | Any | 25 |

| T3 | N1 | M0 | Any | Any | ||

| T4a | N0 | M0 | Any | Any | ||

| Stage IIIB | T3 | N2 | M0 | Any | Any | 17 |

| Stage IIIC | T4a | N1-2 | M0 | Any | Any | 14 |

| T4b | Any | M0 | Any | Any | ||

| Any | N3 | M0 | Any | Any | ||

| Stage IV | Any | Any | M1 | Any | Any | <5 |

| Stage Grouping (Adenocarcinoma) | ||||||

| T | N | M | Grade | 5-Yr Survival (%) | ||

| Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | 1, X | 82 | |

| Stage IA | T1 | N0 | M0 | 1-2, X | 78 | |

| Stage IB | T1 | N0 | M0 | 3 | 63 | |

| T2 | N0 | M0 | 1-2, X | |||

| Stage IIA | T2 | N0 | M0 | 3 | 50 | |

| Stage IIB | T3 | N0 | M0 | Any | 40 | |

| T1-2 | N1 | M0 | Any | |||

| Stage IIIA | T1-2 | N2 | M0 | Any | 25 | |

| T3 | N1 | M0 | Any | |||

| T4a | N0 | M0 | Any | |||

| Stage IIIB | T3 | N2 | M0 | Any | 17 | |

| Stage IIIC | T4a | N1-2 | M0 | Any | 14 | |

| T4b | Any | M0 | Any | |||

| Any | N3 | M0 | Any | |||

| Stage IV | Any | Any | M1 | Any | <5 | |

* Location of tumor: Position of proximal edge of tumor in the esophagus. Lower: Below inferior pulmonary vein, approximately 30-40 cm from incisors. Middle: From azygos vein to inferior pulmonary vein, approximately 25-30 cm from incisors. Upper: From hypopharynx to azygos vein, approximately 15-25 cm from incisors.

X, Cannot be determined.

Data from Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

The mainstay of treatment for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is surgical resection, most commonly transthoracic esophagectomy. As mentioned previously, early (intramucosal or submucosal) carcinomas in selected patients have been managed with endoscopic resection, with low rates of tumor recurrence or metastasis in specialized centers.60 For those with more advanced but potentially resectable (stage II and III) tumors, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery induces tumor regression and improves survival in a subset of patients.85,88

Variants of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Basaloid Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical Features

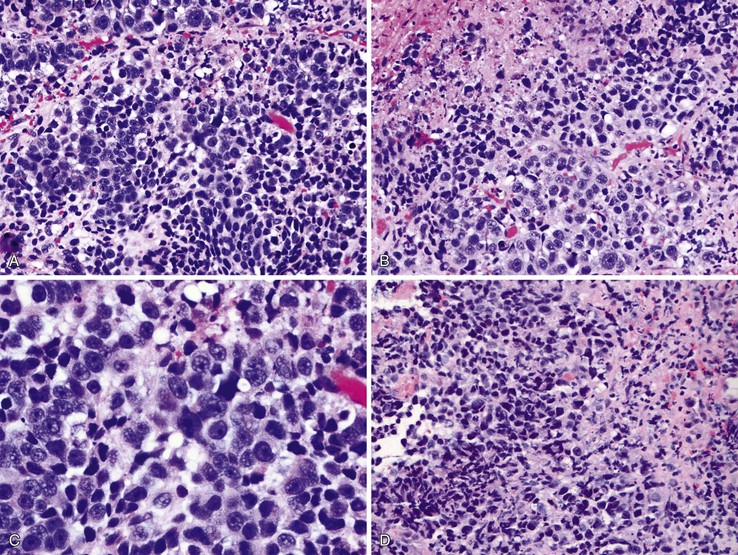

Basaloid (squamous) carcinoma is an unusual variant of squamous cell carcinoma that also occurs in the upper aerodigestive tract (e.g., hypopharynx, base of tongue). The true incidence of esophageal basaloid squamous carcinoma is unknown, but it has been reported to represent 1% to 11% of squamous cell carcinomas.89–91 These tumors, like conventional squamous cell carcinomas, characteristically occur in older men with presenting symptoms of dysphagia and weight loss.

Pathologic Features

Grossly, basaloid squamous carcinomas are large, bulky, fungating tumors that frequently ulcerate and form strictures. They most commonly arise in the middle and distal esophagus.

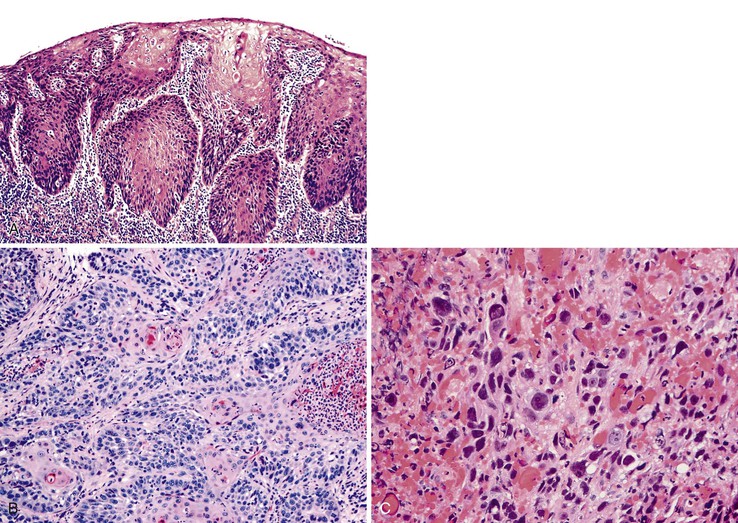

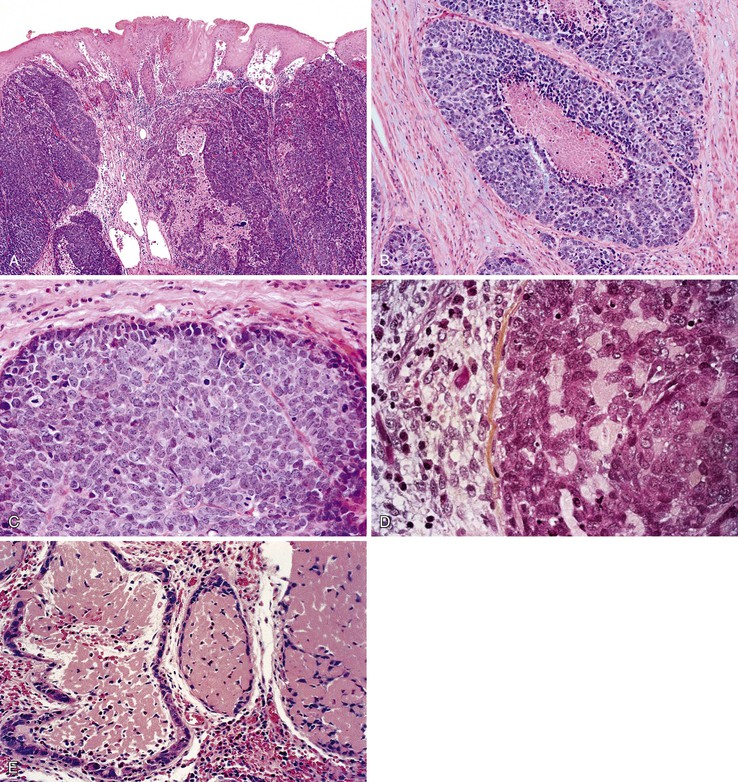

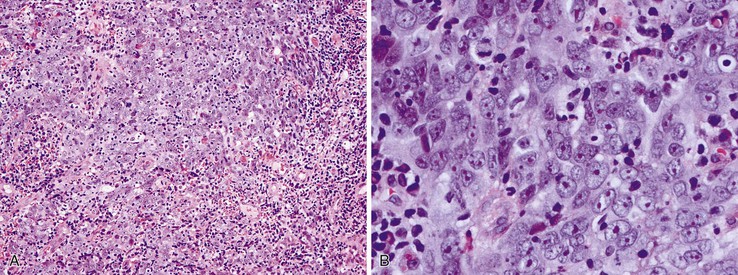

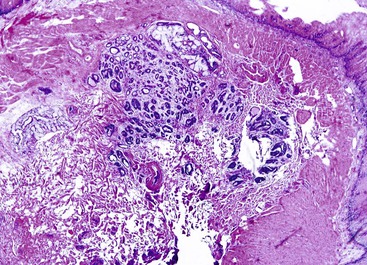

Microscopically, the basaloid component comprises anywhere from 5% to 90% of the tumor and shows a variety of morphologies such as solid, cribriform, trabecular, and ductal growth patterns.89 The characteristic basaloid tumor cells are oval to round, large, and somewhat pleomorphic with an open pale chromatin pattern, small nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm; cells are arranged in solid or cribriform lobules, often showing central necrosis and peripheral palisading (Fig. 24.14). Mitoses are usually easily identifiable. An in situ or invasive squamous cell carcinoma component is often present, at least focally. For example, in one study of 18 basaloid carcinomas, 72% of cases showed areas of squamous cell carcinoma, 50% of which also had in situ squamous cell carcinoma.90 In addition, other lines of differentiation, including adenocarcinoma, small cell carcinoma, or even spindle cell carcinoma may coexist with the basaloid component.91 On the basis of these findings, basaloid carcinoma has been proposed to arise from a multipotential stem cell, or basal cell, in the native squamous epithelium.

Special Studies

A mucoid matrix that stains positive for periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and Alcian blue may be present in the cribriform spaces of some tumor cell nests. By immunohistochemistry, basaloid carcinomas typically show weak staining for broad-spectrum keratins (in a membrane-type pattern) and for TP63 and absence of staining for the neuroendocrine markers neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and S100. The basal cells stain strongly for CK14 and CK19.89,91–93 Some tumors show focal actin and vimentin positivity in the basaloid cells and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) positivity in the pseudoglandular spaces. At the molecular level, basaloid carcinomas are similar to conventional squamous cell carcinomas, particularly with regard to the frequency of alterations of cyclin D1, and the TP53 and retinoblastoma (RB) tumor suppressor genes.91,94 However, these tumors are consistently negative for HPV.91

Differential Diagnosis

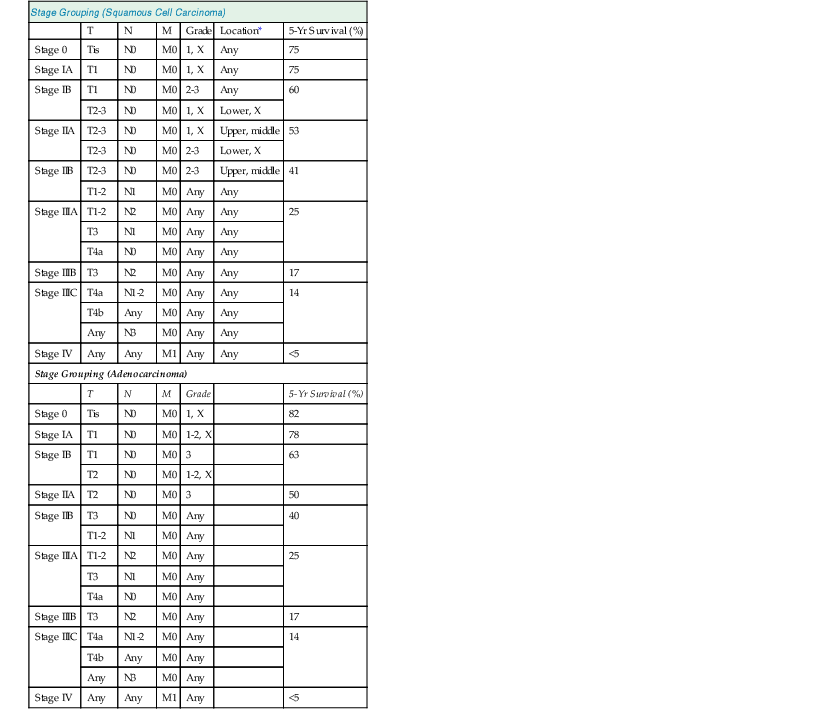

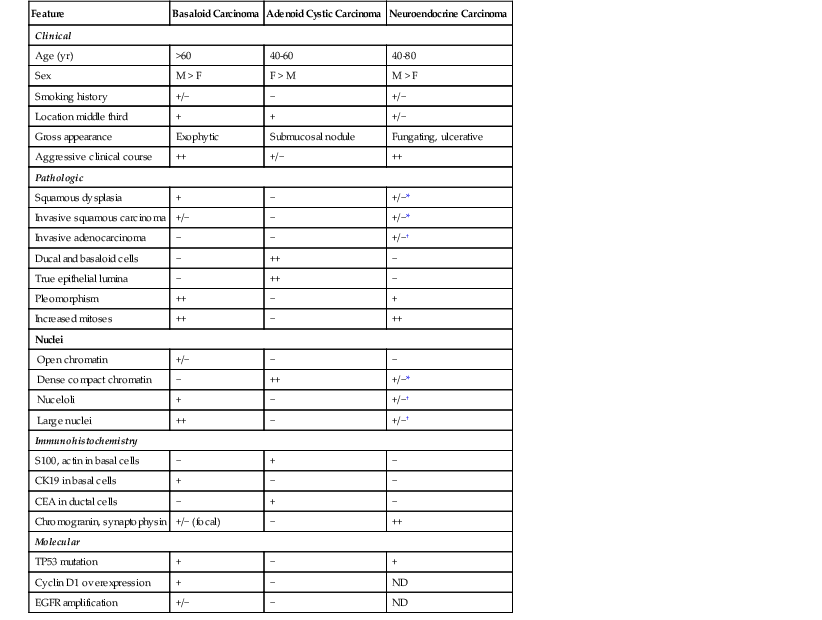

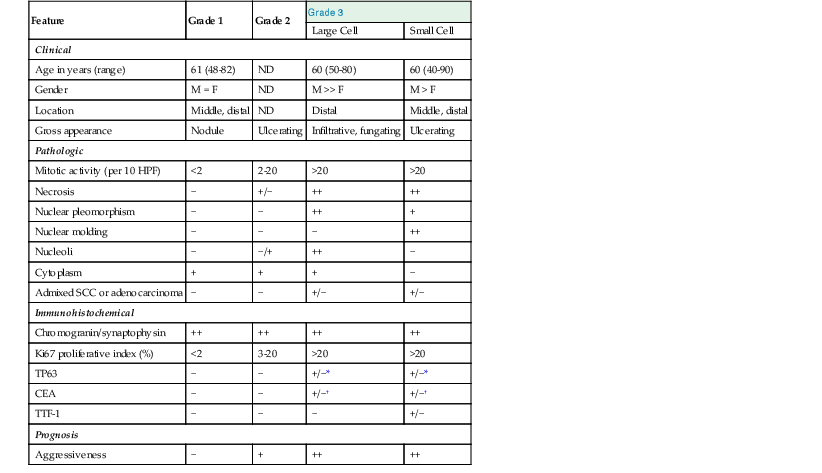

The differential diagnosis of basaloid carcinoma includes conventional (pure) squamous cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC). Cases with a prominent basaloid mucoid matrix (Alcian blue positive, PAS positive) or extensive necrosis can adopt a pseudoacinar or cribriform pattern that may be mistaken for adenoid cystic carcinoma (see Fig. 24.14, D and E). This is an important distinction, because true adenoid cystic carcinomas of the esophagus are less aggressive than basaloid carcinomas (see Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma). Unlike basaloid carcinomas, adenoid cystic carcinomas form true epithelial lumina, do not coexist with conventional squamous cell carcinoma or squamous dysplasia, and lack significant pleomorphism, mitoses, and necrosis (see Fig. 24.25). The basal cells of adenoid cystic carcinoma are smaller and more hyperchromatic and regular in size compared with basaloid carcinoma, and they stain strongly for S100 and actin, whereas the basal cells of basaloid carcinoma are typically positive for CK14 and CK19.92,93 In conventional squamous cell carcinomas, a significant proportion of tumor cells have eosinophilic cytoplasm, grow in irregular infiltrative clusters rather than in rounded nests, and show focal keratinization. However, the distinction between basaloid and squamous carcinoma may be arbitrary and of little prognostic value. The differential diagnosis of basaloid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and NEC is summarized in Table 24.4.

Table 24.4

Basaloid Squamous Carcinoma versus Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma and Neuroendocrine Carcinoma

| Feature | Basaloid Carcinoma | Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma | Neuroendocrine Carcinoma |

| Clinical | |||

| Age (yr) | >60 | 40-60 | 40-80 |

| Sex | M > F | F > M | M > F |

| Smoking history | +/− | − | +/− |

| Location middle third | + | + | +/− |

| Gross appearance | Exophytic | Submucosal nodule | Fungating, ulcerative |

| Aggressive clinical course | ++ | +/− | ++ |

| Pathologic | |||

| Squamous dysplasia | + | − | +/−* |

| Invasive squamous carcinoma | +/− | − | +/−* |

| Invasive adenocarcinoma | − | − | +/−† |

| Ducal and basaloid cells | − | ++ | − |

| True epithelial lumina | − | ++ | − |

| Pleomorphism | ++ | − | + |

| Increased mitoses | ++ | − | ++ |

| Nuclei | |||

| Open chromatin | +/− | − | − |

| Dense compact chromatin | − | ++ | +/−* |

| Nuceloli | + | − | +/−† |

| Large nuclei | ++ | − | +/−† |

| Immunohistochemistry | |||

| S100, actin in basal cells | − | + | − |

| CK19 in basal cells | + | − | − |

| CEA in ductal cells | − | + | − |

| Chromogranin, synaptophysin | +/− (focal) | − | ++ |

| Molecular | |||

| TP53 mutation | + | − | + |

| Cyclin D1 overexpression | + | − | ND |

| EGFR amplification | +/− | − | ND |

* Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

† Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

CEA, Carcinoembryonic antigen; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ND, not determined; +, consistently present; ++, key feature; −, not present.

Differentiation of basaloid carcinoma from NEC is usually easily and best performed by immunohistochemical staining with chromogranin, synaptophysin, Leu-7, or CD56. Basaloid carcinomas may show focal and rare weak staining with endocrine markers, but this contrasts greatly with diffuse strong staining in most NECs. Although small cell carcinoma may show only weak or focal staining, these tumors are characterized by the presence of small hyperchromatic cells without nucleoli and with prominent nuclear molding. This contrasts with basaloid carcinomas, which have larger nuclei, lack molding, and have prominent nucleoli.

Prognosis

Basaloid squamous carcinoma is a highly aggressive tumor that carries a prognosis similar to that of pure squamous cell carcinoma. Although prognostic information is limited because of the relative rarity of this tumor type, the available studies show no difference in overall survival between these two tumor types.90

Carcinosarcoma

Clinical Features

Carcinosarcoma, also known as polypoid carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma, and sarcomatoid carcinoma, was first described by Virchow in 1865; it represents approximately 2% of esophageal carcinomas. Similar to squamous cell carcinoma, it predominantly affects men (80%) in middle to late adult life (40 to 90 years).95 Because of the typical exophytic intraluminal growth pattern of these tumors, presenting symptoms are commonly related to esophageal obstruction.

Pathologic Features

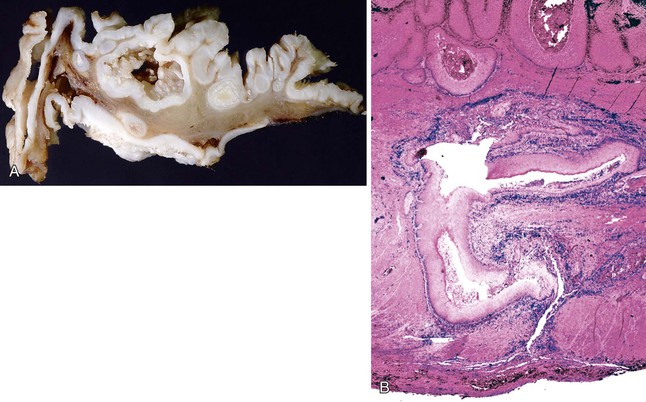

Grossly, these tumors may grow to large sizes (1 to 25 cm) and show a predilection for the middle and distal segments of the esophagus. Eighty percent of lesions are polypoid and have an exophytic growth pattern (Fig. 24.15), whereas only 10% of cases show an infiltrative growth pattern.

Microscopically, the tumor is characterized by a combination of epithelial and spindle cell (or other mesenchymal) elements (Fig. 24.16). The epithelial element is typically moderately to well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. In some cases, only in situ carcinoma is present.95 In fact, some cases show only a small amount of the epithelial component, and this is usually either at the base of the polyp or at the periphery of the invasive tumor. The sarcomatous component is commonly a high-grade spindle cell sarcoma. However, osteosarcomatous, rhabdomyosarcomatous, or chondrosarcomatous differentiation may be present as well.

Immunohistochemically, the epithelial component is typically keratin positive, whereas the sarcomatous component usually stains with vimentin. However, keratin or vimentin may be seen occasionally in either component of the tumor.

By electron microscopy, a mixture of cell types has been identified, ranging from pure epithelial cells, to cells that show a combination of epithelial and sarcomatous features, to cells with pure sarcomatous differentiation.96 It is these ultrastructural findings, combined with the histologic finding in most cases of areas of transition between epithelial and sarcomatous differentiation, that have led to the prevailing theory that these tumors are derived from diverse differentiation (metaplasia) of the carcinomatous element. In addition, molecular studies have found shared chromosome losses and mutations in both the carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements, with additional changes found only in the sarcomatous areas, further supporting this theory of histogenesis.97 In another study of 20 cases, the sarcomatous and carcinomatous areas showed similar Ki67 proliferation indices.98

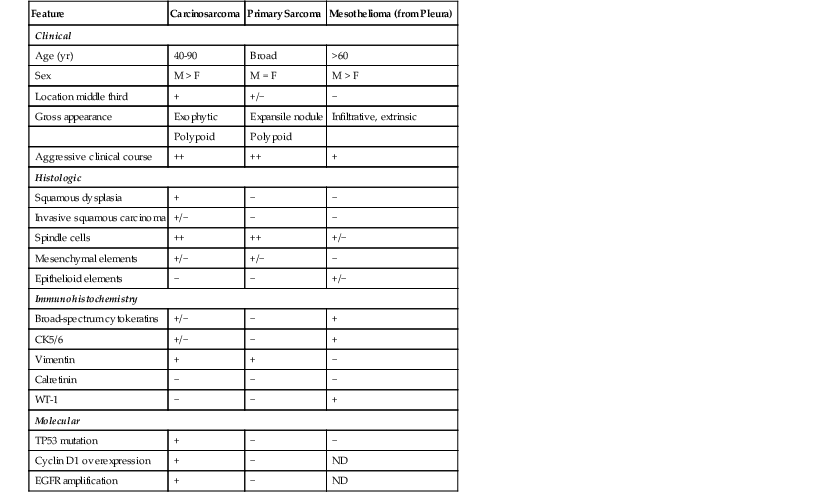

Differential Diagnosis

Esophageal carcinosarcomas must be differentiated from pure sarcomas (e.g., liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma), including those primary to the esophagus and those involving the esophagus by direct spread or metastasis. Recognition of the distinctive gross features and pattern of esophageal involvement, as well as the presence of malignant or premalignant epithelial elements, strongly favors a diagnosis of carcinosarcoma (Table 24.5). Extensive sampling of the tumor and cytokeratin immunostains may be necessary. On occasion, biphasic malignant mesotheliomas may spread from the pleura to involve the esophagus, but these are distinguished by the appropriate clinical history and by the distinctive immunophenotype of mesothelioma (positive for CK5/6, mesothelin, WT-1, and calretinin; negative for CEA and Leu-M1).99

Table 24.5

Esophageal Carcinosarcoma versus Primary Sarcoma and Mesothelioma

| Feature | Carcinosarcoma | Primary Sarcoma | Mesothelioma (from Pleura) |

| Clinical | |||

| Age (yr) | 40-90 | Broad | >60 |

| Sex | M > F | M = F | M > F |

| Location middle third | + | +/− | − |

| Gross appearance | Exophytic | Expansile nodule | Infiltrative, extrinsic |

| Polypoid | Polypoid | ||

| Aggressive clinical course | ++ | ++ | + |

| Histologic | |||

| Squamous dysplasia | + | − | − |

| Invasive squamous carcinoma | +/− | − | − |

| Spindle cells | ++ | ++ | +/− |

| Mesenchymal elements | +/− | +/− | − |

| Epithelioid elements | − | − | +/− |

| Immunohistochemistry | |||

| Broad-spectrum cytokeratins | +/− | − | + |

| CK5/6 | +/− | − | + |

| Vimentin | + | + | − |

| Calretinin | − | − | − |

| WT-1 | − | − | + |

| Molecular | |||

| TP53 mutation | + | − | − |

| Cyclin D1 overexpression | + | − | ND |

| EGFR amplification | + | − | ND |

EGFR, Epidermal growth factor receptor; ND, not determined; +, consistently present; ++, key feature; −, not present.

Prognosis

Carcinosarcomas are potentially aggressive tumors, with roughly 50% of cases having lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis. Nevertheless, the overall survival rate for this tumor type in recent series has approached 60% (better than conventional squamous cell carcinoma), in part reflecting the larger proportion of tumors detected at an early stage because of their exophytic growth.95,98 The sarcomatous component usually exhibits a more aggressive biologic behavior and a higher propensity to metastasize.

Verrucous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical Features

Verrucous carcinoma of the esophagus is an extremely rare low-grade malignant neoplasm, first described in the oral cavity by Ackerman in 1948, with approximately 20 cases reported. Affected patients range from 36 to 76 years of age, and the disease has a male predilection. These tumors may grow very large before the onset of symptoms, with a resultant long delay in diagnosis. Presenting complaints are usually dysphagia, weight loss, coughing, and hematemesis. The pathogenesis has been related to various causes of chronic mucosal irritation such as caustic injury (lye), achalasia, lichen planus, diverticular disease, and GERD.100,101 A circumstantial association with esophageal HPV infection was reported in one patient.102

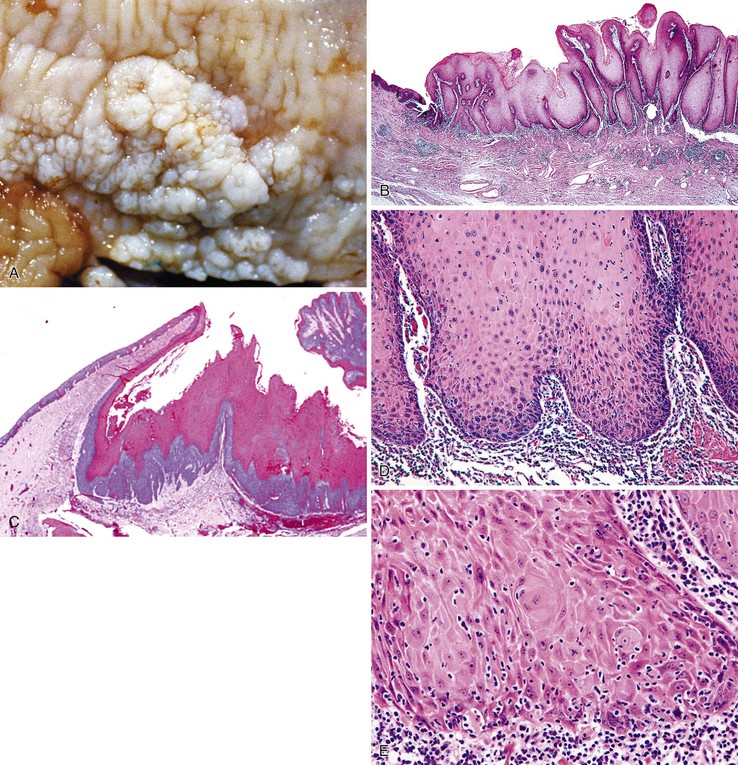

Pathologic Features

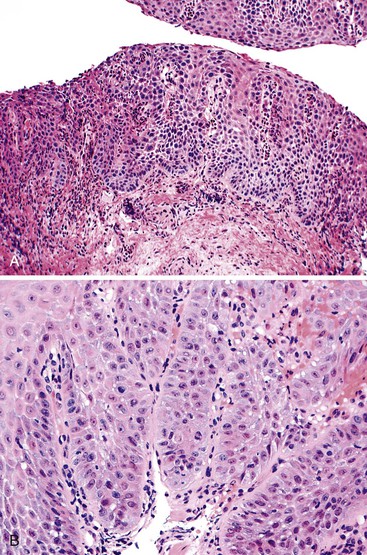

Pathologically, verrucous carcinomas have an exophytic papillary growth pattern and often occupy most, or even the entire, circumference of the esophageal lumen. These tumors show characteristic luminal stricturing and erosion, with necrotic and keratinaceous surface debris. Microscopically, the characteristic features are those of a very well-differentiated verrucoid, or papillomatous, proliferation of squamous cells with mild cytologic atypia, prominent acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, swollen rete pegs, and inflammation (Fig. 24.17). Invasion is usually difficult to assess because it is typically in the form of broad pushing margins. Classic tumors show a central “crater” of keratin with heaped up edges due to acanthotic squamous epithelium. Mitoses may be limited to the basal layers of the tumor or, rarely, scattered in the mid layers as well. Although the degree of cytologic atypia is considered “mild,” often the cells are larger in size than their benign counterparts and show enlarged nuclei with irregular nuclear contours, prominent nucleoli, and slight pleomorphism with loss of polarity. These features may extend several layers above the basal layer of the squamous epithelium. Furthermore, some areas of these tumors may show lack of surface maturation. A mild inflammatory response at the tumor–stroma interface is common.

Differential Diagnosis

The key disease in the differential diagnosis is benign squamous papilloma (see Table 24.1). Clinical and endoscopic findings are usually helpful in differentiating these two tumors. Squamous papillomas are small (<3 cm), localized, discrete lesions, whereas verrucous carcinomas more commonly show extensive or circumferential involvement of the esophageal wall. Microscopically, papillomas may display koilocytosis and do not show a pushing deep margin, submucosal extension, or the mild but definite cytologic atypia of verrucous carcinomas. Accordingly, pathologists should be cautious about making a diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma based on a biopsy specimen because the superficial aspects of both lesions may be indistinguishable, and both may even be mistaken for regenerative epithelium if the endoscopic findings are unknown.

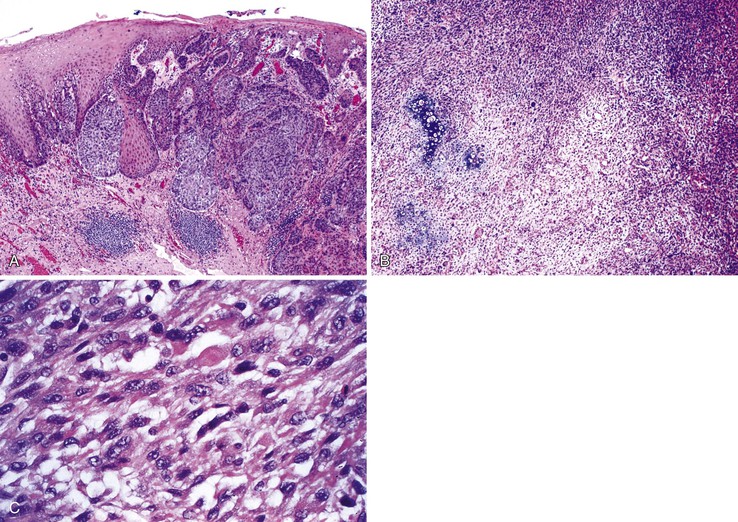

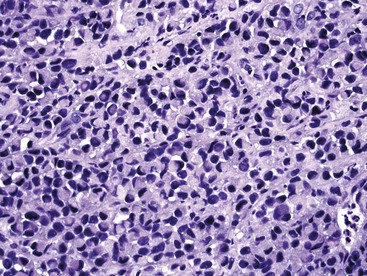

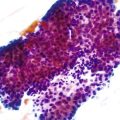

Lymphoepithelioma-Like Carcinoma

A small number of esophageal carcinomas display an undifferentiated phenotype and are associated with a prominent lymphoid infiltrate, similar to lymphoepitheliomas of the nasopharynx. Most cases have been reported from Japan and have clinically resembled conventional squamous cell carcinomas.66,106 These tumors are histologically identical to their counterpart in the nasopharynx, showing syncytia of primitive-appearing epithelioid cells surrounded by a dense inflammatory infiltrate including lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 24.18). By analogy with the tumors in these other organs, Epstein-Barr virus has been suggested as an etiologic agent. However, the virus has been detected in only a minority of esophageal tumors by various methods, including in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and DNA amplification.107,108 Although the clinical behavior of these tumors is incompletely understood because of their rarity, some authors have suggested that they have a slightly better prognosis than ordinary squamous cell carcinomas.106

Esophageal Carcinoma Cuniculatum

Carcinoma cuniculatum is an unusual, extremely well-differentiated variant of squamous cell carcinoma that has been reported in approximately 9 patients.109 The tumor is more common in men (male-to-female ratio, 7 : 2), with a mean age of 57 years, who present with a distal esophageal mass (mean size, 4 cm). Grossly, this tumor type is notable for the presence of prominent surface furrows or sinuses (Fig. 24.19). Microscopically, the furrows correspond to keratin-filled cysts or cavities surrounded by acanthotic, hyperkeratotic squamous epithelium with only mild atypia. Squamous dysplasia was not identified in the surrounding mucosa in any of the published cases, and studies for HPV were consistently negative. None of the reported patients showed lymph node metastasis, and none died of disease after surgical resection. Distinction of this tumor type from verrucous carcinoma is difficult and may, in fact, be arbitrary. Indeed, some reported cases of verrucous carcinoma have histologic features that overlap with those of carcinoma cuniculatum.110 Both subtypes of squamous carcinoma are associated with an excellent prognosis if surgical resection is complete and successful.

Adenocarcinoma

More than 95% of esophageal adenocarcinomas develop in association with BE (Table 24.6). Adenocarcinomas may also develop from esophageal submucosal glands or ducts or from foci of heterotopic epithelium, but these tumors are extremely rare (see Non–Barrett’s-Associated Adenocarcinoma). Adenocarcinomas that arise at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) or gastric cardia are discussed further in Chapter 25.

Table 24.6

Barrett’s Esophagus (BE)-Associated Adenocarcinoma versus Gastric Cardia Adenocarcinoma

| Feature | BE-Associated Adenocarcinoma | Gastric (Cardia) Adenocarcinoma |

| Clinical | ||

| Age (yr) | >60 | 40-60 |

| Sex | M > F | F = M |

| GERD risk factor | ++ | +/− |

| Helicobacter pylori risk factor | − | +/− |

| Location relative to GEJ | Proximal | Distal |

| Gross appearance | Exophytic, ulcerative | Fungating |

| Pathologic | ||

| Adjacent BE | + | − |

| Adjacent gastric intestinal metaplasia | − | + |

| Tubular type | + | + |

| Mucinous type | +/− (10-15%) | +/− |

| Signet ring cell type | +/− | +/− |

| Immunohistochemistry | ||

| CK7+/CK20− | ++ | +/− |

| CDX2 | + | + |

| Chromogranin, synaptophysin | +/− (focal) | +/− (focal) |

| Molecular | ||

| TP53 mutation | + | + |

| HER2 amplification | +/− | +/− |

| EGFR amplification | +/− | +/− |

EGFR, Epidermal growth factor receptor; GEJ, gastroesophageal junction; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; +, consistently present; ++, key feature; −, not present.

Clinical Features

The incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus has increased dramatically in the last two to 3 decades. This tumor now constitutes more than 50% of all esophageal carcinomas diagnosed in the United States, and it is the most common tumor in the distal esophagus.1,2,38 In 2010, the overall incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in the United States was estimated at 2.5 per 100,000 population.111

The demographic characteristics of patients with adenocarcinoma are similar to those of patients with BE. BE-associated adenocarcinoma affects predominantly older men (mean age, 60 years; male-to-female ratio, 3 : 1 to 7 : 1), and more than 80% of patients are white.2,38,111 Depending on the size and location of the tumor, patients may present with dysphagia, odynophagia, or obstruction. Progressive dysphagia and weight loss are ominous signs that are usually associated with advanced disease.

Pathogenesis and Risk Factors

The most significant risk factor for adenocarcinoma is BE, currently defined in the United States by the presence of columnar epithelium (with goblet cells) anywhere in the tubular esophagus; BE develops in approximately 6% to 12% of patients with GERD.112,113 Obesity, most likely through its association with GERD and BE, is associated with an approximately fourfold increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma compared with a normal body mass index.114 Tobacco use confers an elevated risk for developing adenocarcinoma both in the general population and in BE patients, although the magnitude of risk (approximately 1.5- to 2-fold) does not approach the levels observed for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.115 No consistent association between alcohol use and adenocarcinoma has been found in recent epidemiologic studies.116

The overall prevalence of adenocarcinoma in patients with BE was estimated to be between 5% and 28% in early studies.117 However, many of the early studies of adenocarcinoma in patients with BE were retrospective and overestimated the magnitude of risk.118 More recent studies suggest that patients with BE have an approximately 11-fold increased risk for the development of adenocarcinoma compared with the general population.119 Indeed, only a small percentage of patients with BE (1% to 5%, or 0.1% to 0.5% per year) develop adenocarcinoma when followed prospectively.120–126 Factors that increase the risk for adenocarcinoma include the presence, grade, and extent of dysplasia in BE120,123,127,128; the presence of DNA aneuploidy in BE127; greater lengths of BE120,129; and the presence of a hiatus hernia.129,130 As noted earlier, tobacco use also contributes to the risk of malignant progression in BE patients.115

Intestinal (Goblet Cell) versus Nonintestinal (Nongoblet) Columnar Metaplasia

One current area of controversy concerns the magnitude of risk for adenocarcinoma in patients with metaplastic esophageal columnar mucosa without intestinal metaplasia (goblet cells). Although intestinal (goblet cell) metaplasia has traditionally been used to define BE, biopsy specimens from columnar-lined esophageal segments may contain large areas devoid of goblet cells, and these nonintestinalized areas have been found to harbor genetic alterations associated with neoplastic progression.131–133 A retrospective study of 712 BE patients found that the risk for adenocarcinoma was similar whether the index esophageal biopsy samples had glandular mucosa with intestinal metaplasia or nonintestinalized glandular mucosa (4.5% and 3.6%, respectively, after a 12-year follow-up period).134 Furthermore, in a series of 141 BE-associated “early” adenocarcinomas, 57% occurred within nongoblet columnar mucosa.135 Although additional population-based and preferably prospective studies are needed to more precisely define the relative importance of nonintestinal mucosa as a precursor to adenocarcinoma, current evidence suggests that this pathway accounts for a definite, albeit small, percentage of malignant esophageal tumors.

Molecular Features

The molecular genetic alterations that underlie the development of BE-associated adenocarcinoma have been the subject of extensive study.48,136 Similar to most epithelial malignancies, esophageal adenocarcinomas show alterations in multiple genetic loci (genomic instability), which are acquired in a stepwise fashion during the progression of dysplasia to carcinoma. Among the most common are inactivation (through mutation or transcriptional silencing) of the tumor suppressor proteins p16, p27, p53 and of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene (75% to 92% of tumors) and overexpression or amplification of cyclin D1 (22% to 64% of cases).137,138 Amplification of the genes for the growth factor receptor EGFR (13% to 30%), ERBB2/HER2 (15% to 25%), and MET (2%), although present in only a minority of adenocarcinomas, have significant therapeutic implications.139–141 Downregulation of p16, mutation of p53, and upregulation of cyclin D1 are early abnormalities that occur even before the onset of morphologic dysplasia. For example, methylation, loss of heterozygosity (LOH), or mutations in p16 have been observed in as much as 80% of BE patients before the onset of dysplasia or carcinoma.138

Widespread genomic instability is the molecular hallmark of progression to malignancy, and it is believed to be the cause, not the consequence, of carcinogenesis in BE.136 Most, if not all, chromosomes are affected in this process, either by increased number or by alteration of content (e.g., additions, deletions). In fact, alterations in DNA content (aneuploidy) in nondysplastic BE is a strong predictor of progression to high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma.127,142 By contrast, DNA mismatch repair defects resulting in microsatellite instability occur infrequently (5% to 10%) in BE-associated adenocarcinomas.143 Abnormalities in DNA content can be measured in a variety of ways, including fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), chromosomal karyotyping, comparative genomic hybridization, flow cytometry, and, more recently, image cytometry. Some of these techniques are currently being investigated and have been proposed as potentially providing prognostic markers in BE patients.127,130,133,142 However, at present, no specific biomarkers or biomarker panel has been recommended for routine clinical use to help manage BE by potentially altering the frequency of surveillance endoscopies.144

Pathologic Features

Gross Pathology

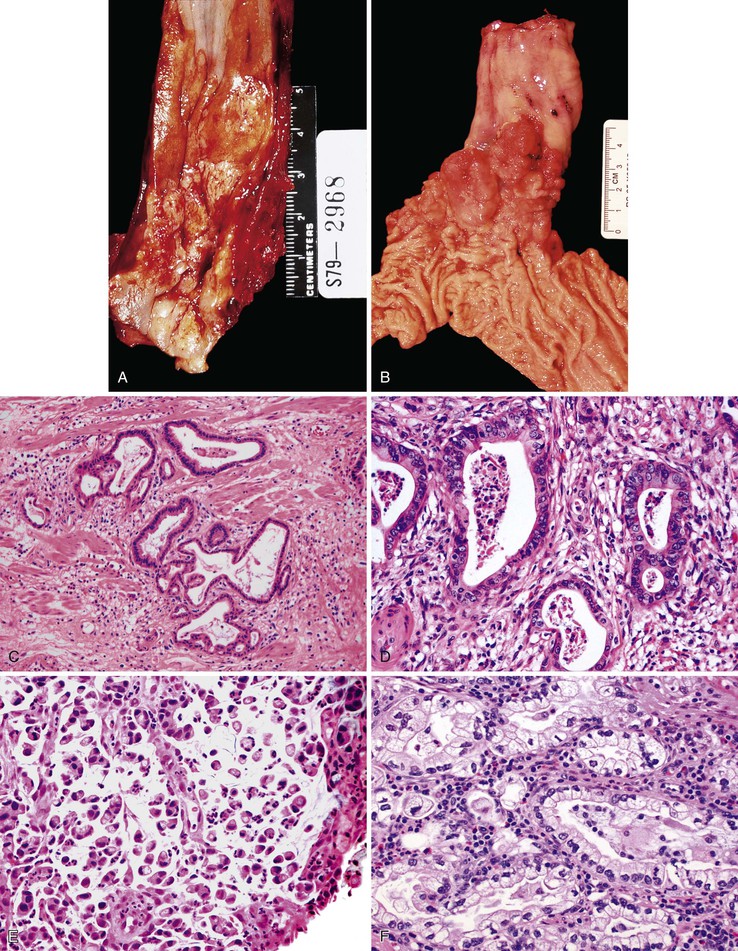

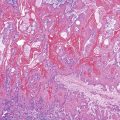

BE-associated adenocarcinomas are located almost exclusively in the distal third of the esophagus in areas of involvement with BE. Distal tumors frequently show extension into the proximal stomach. They may be classified as polypoid (protruding) (5% to 10%), flat (10% to 15%), fungating (20% to 25%), or infiltrative (40% to 50%) (Fig. 24.20, A and B).39,145 Early carcinomas may be undetectable or may appear only as slightly irregular, depressed or elevated lesions.146 Diffusely infiltrative tumors are uncommon. Large tumors may obliterate the underlying or adjacent Barrett’s mucosa, particularly those that arise in the distal esophagus at or near the level of the GEJ. In such instances, it may occasionally be difficult to determine whether an adenocarcinoma located near or at the GEJ is, in fact, esophageal (BE-related) or gastric in origin. Also, patients who have been treated with preoperative chemotherapy or radiation therapy may have little or no gross residual tumor left in their resection specimen. In fact, as much as 50% of patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy show either no, or only minimal, microscopic residual tumor after surgery.147,148

Microscopic Pathology

These tumors, like squamous cell carcinomas, typically spread vertically through the esophageal wall and metastasize to regional lymph nodes. Adenocarcinomas are graded as well, moderately, or poorly differentiated. The AJCC grading system classifies tumors by the proportion of tumor that is composed of glands.81 However, most tumors are moderately or well differentiated.39,145 Some tumors show variations in grade within the same tumor, and the highest grade is usually recorded for prognostic purposes.

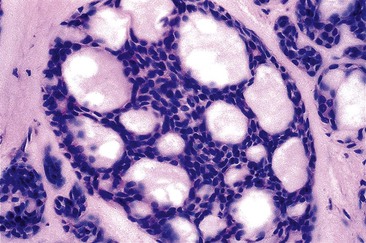

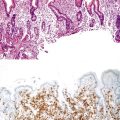

Well-differentiated carcinomas (i.e., >95% of tumor composed of glands) are made almost entirely of irregularly shaped or cystic glandular and tubular profiles that infiltrate the mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis (see Fig. 24.20, C). The tumor cells are cuboidal to columnar in shape and contain irregular nuclei with coarse or vesicular chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and a variable amount of eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm. In moderately differentiated carcinomas (50% to 95% of tumor composed of glands), tumor cells are arranged in solid nests and irregular clusters as well as glands (see Fig. 24.20, D). In these tumors, the cells within the glandular profiles may adopt a cribriform pattern and show considerable stratification. Poorly differentiated carcinomas (5% to 49% of tumor composed of glands) often infiltrate the esophageal wall in a diffuse manner and usually with a prominent desmoplastic stroma. The tumor cells are arranged in sheets and in poorly formed glandular lumina; signet ring cells and bizarre pleomorphic tumor cells may be present. Interestingly, a subset of poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas involve the surface squamous epithelium in the form of single cells that grow in a pagetoid fashion.58 Other intestinal cell types, such as Paneth cells and endocrine cells,149 are present focally in as much as 20% of adenocarcinomas.

Approximately 5% to 10% of adenocarcinomas contain areas of mucinous (colloid) histology, characterized by tumor cell clusters floating in pools of mucin. Another 5% contain areas of infiltrating signet ring cells (see Fig. 24.20, E), and occasional cases show clear cell morphology (see Fig. 24.20, F).145,150 Occasional tumors may show multidirectional differentiation, with coincident areas of glandular, squamous, or neuroendocrine differentiation (see later discussion).

In patients treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy, residual tumor cells may be present merely as individual cells or as small, isolated clusters of cells, in association with ulceration, dense fibrosis, or pools of mucin.147,148 These cells are frequently pleomorphic, showing extreme nuclear irregularity and enlargement; on occasion, they may be difficult to distinguish from reactive mesenchymal cells. Immunohistochemistry for keratins often helps in this situation, being generally positive in the tumor cells and negative in the mesenchymal cells. Clusters of residual keratin-positive endocrine cells may be present in the deep lamina propria of treated areas, but these should not be mistaken for residual carcinoma.151 Sometimes, the only sign of a treated tumor is acellular pools of mucin dissecting through the layers of the esophageal wall (Fig. 24.21). However, acellular mucin pools do not result in an increased risk of recurrence or metastasis.145

Special Studies

Special studies are not usually necessary to establish a diagnosis of esophageal adenocarcinoma, but they can occasionally be useful in characterizing poorly differentiated lesions, identifying resections with little or no residual tumor after neoadjuvant therapy, or distinguishing primary esophageal tumors from metastases. Tumor cells are positive for mucin by histochemical stains including mucicarmine, PAS-diastase, and Alcian blue, although positive cells may be rare or nonexistent in poorly differentiated tumors. Adenocarcinomas stain positively with broad-spectrum anticytokeratin antibodies and are positive for CK7 and negative for CK20 in approximately 70% to 90% of cases.152 Reactivity for the intestine-specific transcription factor CDX2 is present in 34% to 70% of cases.153 Although detailed studies have not been published, in our experience these tumors are negative for the lung/thyroid epithelial marker TTF-1. Focal positivity for neuroendocrine markers, such as chromogranin, can be found in 20% to 50% of cases.149,154

Differential Diagnosis

Most of the difficulties related to diagnosing adenocarcinomas occur in the evaluation of endoscopic biopsy specimens, in which the distinction between high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal or invasive carcinoma may be uncertain. Architectural features such as single cell infiltration of the lamina propria, sharply angulated glands, small glands in a back-to-back pattern, confluent glands or a sheetlike growth pattern, and glandular intraluminal necrosis support a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (Fig. 24.22).155 It is not uncommon for dysplastic glands to be situated within the fibers of the muscularis mucosae, which in BE is often duplicated and fragmented. This finding should not be overinterpreted as representing “invasive” tumor unless other features mentioned earlier are also present.

For patients treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy, cytokeratin immunostaining may be necessary to distinguish rare residual tumor cells from mesenchymal cells with treatment effect.

In some patients, it may be necessary to exclude the possibility of metastasis or spread to the esophagus from another primary site such as the stomach, lung, or breast. The presence of BE and dysplastic epithelium adjacent to the carcinoma is normally considered convincing evidence that the tumor has arisen from the esophagus. In addition, primary esophageal adenocarcinomas do not stain for TTF-1 or estrogen receptor,156 markers of lung and breast tumors, respectively.