Epilepsy

Types of seizure

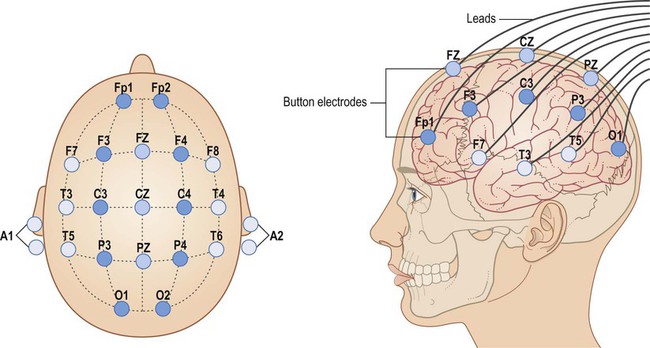

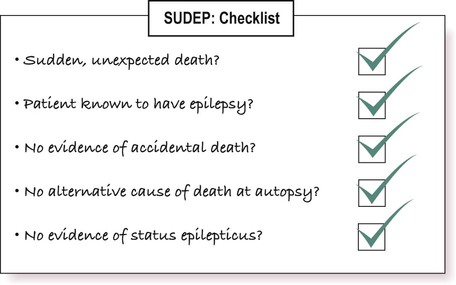

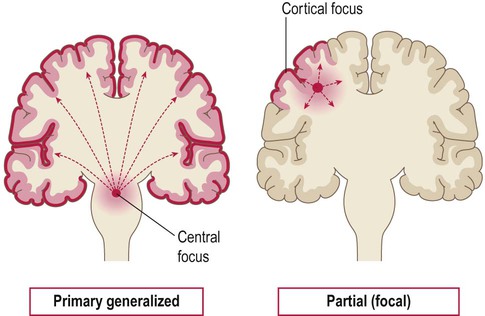

The two main types of seizure are illustrated in Fig. 11.1. Primary generalized seizures diffusely involve both cerebral hemispheres at onset and consciousness is usually lost. Partial (focal) seizures have a discrete cortical origin and the clinical features reflect the function of the affected area. Abnormal electrical activity can often be recorded during a seizure using scalp electrodes (discussed below).

Primary generalized seizures originate from a central focus in the thalamus or brain stem and involve both cerebral hemispheres at onset. Partial (focal) seizures begin in a discrete cortical region and are due to an abnormality in the neighbouring grey or white matter. A focal seizure may spread to become secondarily generalized.

General aspects

There are numerous epilepsy syndromes with differences in seizure type, age at onset, presumed aetiology and EEG findings (Clinical Box 11.1). They can be classified in different ways such as mode of onset (generalized versus focal) or age at presentation. Many epilepsy syndromes arise in childhood and some have highly characteristic features (Clinical Boxes 11.2, 11.3 & 11.4).

Common seizure patterns

Despite the large number of epilepsy syndromes, there are several commonly encountered types of seizure, each with distinctive semiology (clinical manifestations). An example of a simple partial seizure has been described in Clinical Box 11.2; in the following sections, typical features of a complex partial seizure and two very different forms of primary generalized seizure will be described.

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures

Tonic phase (30 seconds)

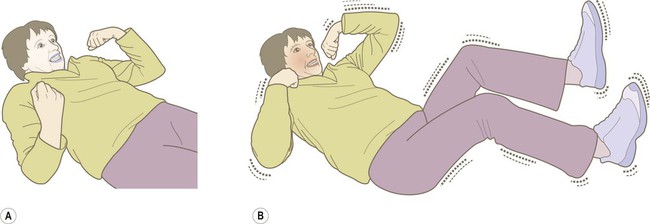

Intense neuronal discharges from the cerebral cortex cause the entire body to become rigid (Fig. 11.4A). Spasm of the laryngeal and respiratory muscles forces air out of the chest, often producing an epileptic cry. The eyes deviate upwards and the patient falls stiffly to the ground, remaining in a state of tonic muscular contraction. Breathing ceases temporarily, leading to cyanosis.

(A) The tonic phase lasts around 30 seconds. The entire body becomes rigid, respiration ceases and the patient becomes cyanotic; (B) The clonic (jerking) phase is characterized by violent symmetrical convulsions, often associated with laboured breathing and frothing at the mouth, typically lasting around 60 seconds.

Clonic phase (60 seconds)

This is characterized by violent, symmetrical convulsions, with muscular contraction and relaxation (Fig. 11.4B). Breathing is noisy and poorly coordinated, with salivation that appears as ‘frothing at the mouth’. The face may be pink and congested or cyanosis may persist if ventilation is poor. Tongue biting and other injuries sometimes occur and the patient may be incontinent of urine. As the clonic phase comes to an end the jerking movements gradually subside.

Diagnosis and management

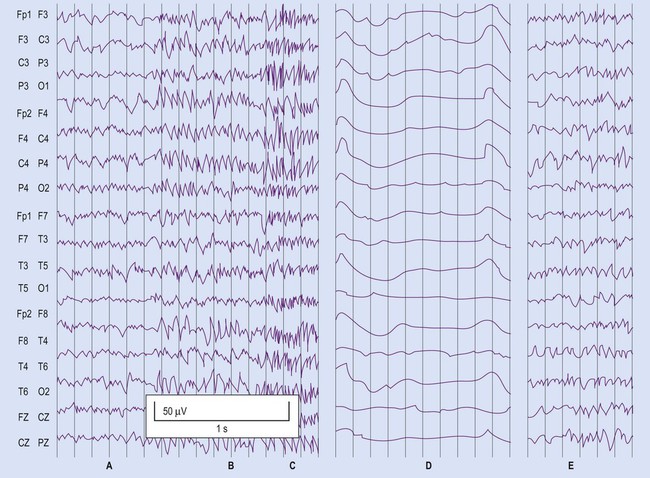

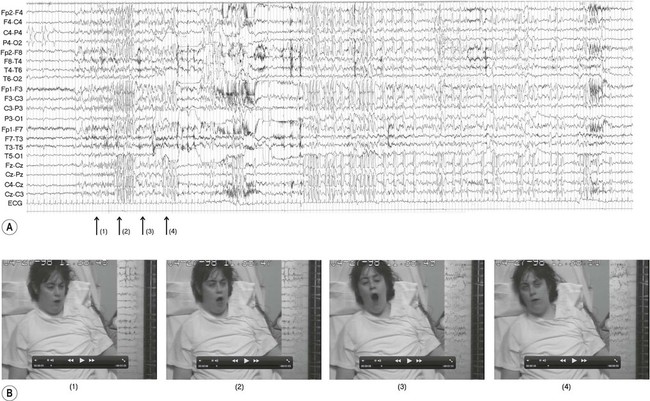

The diagnosis of epilepsy is clinical and requires a detailed eyewitness account of the episodes. If EEG is performed, this may provide evidence to support the clinical diagnosis. Video recording combined with EEG (referred to as telemetry) may be particularly helpful in difficult cases (Fig. 11.5). Epilepsy can usually be managed pharmacologically, but a neurosurgical procedure may be suitable in a minority of cases. In some patients, the less invasive option of a vagus nerve stimulator may be considered (Clinical Box 11.5).

The EEG trace (A) and video sequence (B) capture an ictal event, characterized by involuntary orofacial movements. From Specchio, N et al: Epilepsy and Behavior: Ictal yawning in a patient with drug-resistant focal epilepsy: Video/EEG documentation and review of literature reports. Epilep Behav 2011 Nov; 22(3):602–605 with permission.

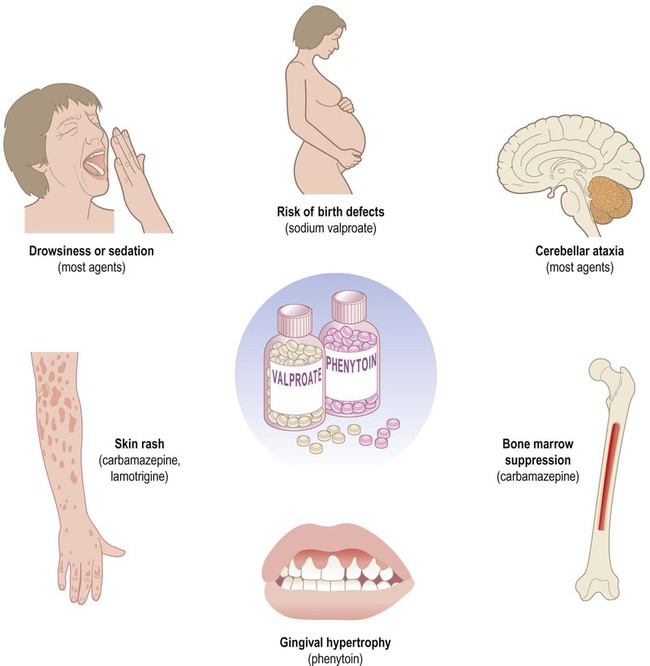

Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs)

Two thirds of patients can be managed effectively with anti-epileptic drugs and adequate control is usually achieved with a single agent (monotherapy). Some of the important side effects of anti-epileptic drugs are discussed in Clinical Box 11.6.

Mechanisms of action

Sodium channel antagonists

Inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels is the most common mechanism. This interferes with the depolarization phase of the action potential, which is mediated by a fast inward sodium (Na+) current. Many agents prolong channel inactivation by preferentially binding to sodium channels in their inactivated state. This increases the refractory period of the neuronal membrane (see Ch. 6). Repetitive neuronal firing at high frequencies is specifically reduced (activity-dependence), minimizing interference with normal brain activity. Examples of agents that block sodium channels include: phenytoin, carbamazepine, sodium valproate and lamotrigine.

GABA potentiators

These drugs increase activity at inhibitory synapses (see Ch. 7). Some act via post-synaptic GABAA receptors which are linked to a chloride ion channel; this stabilizes the neuronal membrane via an inward chloride (Cl–) current. These include (i) benzodiazepines (e.g. clonazepam, diazepam) which increase the frequency of channel opening and (ii) barbiturates (e.g. primidone, phenobarbital) which increase the duration of channel opening. Others act at metabotropic (G-protein-coupled) GABAB receptors which influence second messenger cascades; this causes longer-lasting hyperpolarization of the neuronal membrane by opening potassium channels. Several anti-epileptic agents increase the amount of GABA available by modulating its synthesis (sodium valproate), reuptake (tiagabine), release (gabapentin) or breakdown (vigabatrin).

Surgery in epilepsy

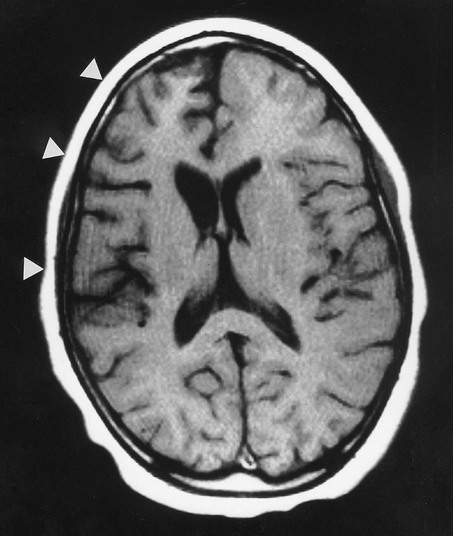

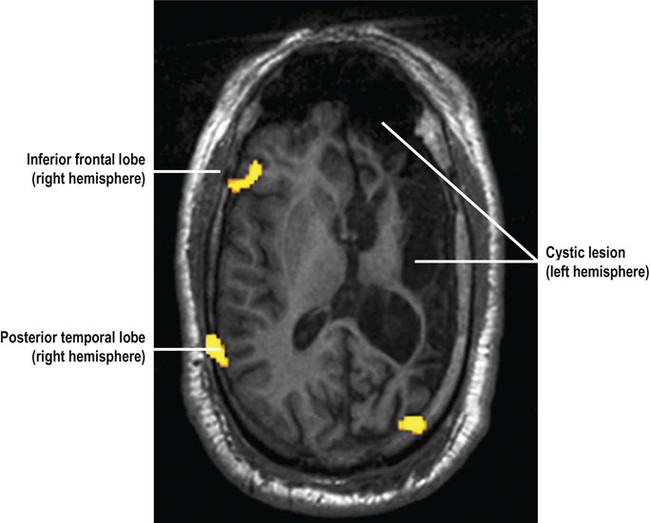

Approximately 10% of patients with drug-resistant focal epilepsy might benefit from a neurosurgical procedure. Before any surgical intervention, detailed preoperative assessment is carried out including psychometric testing and functional brain imaging, to assess the potential impact of surgery on memory, language and intellect (Fig. 11.7).

This patient has a large cystic lesion in the left cerebral hemisphere. The image shows a functional MRI (fMRI) scan in the axial plane during a word generation task used to determine if radical epilepsy surgery is likely to lead to post-operative language impairment. There is increased regional cerebral blood flow in the inferior frontal and posterior temporal regions in the right cerebral hemisphere suggestive of language reorganization to the unaffected (right) side of the brain in this patient which predicts a more favourable outcome following surgery (NB language is normally represented in the left cerebral hemisphere in 95% of right-handed people and 70% of those who are left-handed; see Ch. 3). From Bargalló, Núria: Eur J Radiol 2008 67(3): 401–408 with permission.

Types of procedure

Division of the corpus callosum (callosotomy) can be used to prevent interhemispheric spread of seizures. Resection of an entire cerebral hemisphere (hemispherectomy) or surgical ‘disconnection’ of the cerebral cortex (functional hemispherotomy) is occasionally performed for severe unilateral disease (Clinical Box 11.7).

Neuropathology of epilepsy

Hippocampal sclerosis

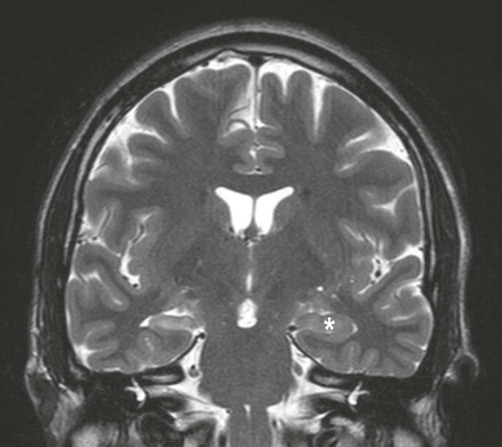

Hippocampal sclerosis is the most common pathological finding in focal epilepsy, accounting for 65% of cases. The typical MRI findings are unilateral volume loss on T1-weighted images and increased signal (hyperintensity) on T2-weighted images (Fig. 11.9). Resected surgical specimens usually appear shrunken and may feel firm or sclerotic when they are sliced (Greek: sklerōs, hard).

Coronal, T2-weighted MRI scan showing unilateral volume loss and T2 hyperintensity in comparison to the normal hippocampus (*) with associated enlargement of the lateral ventricle. Courtesy of Dr Andrew MacKinnon.

Microscopic features

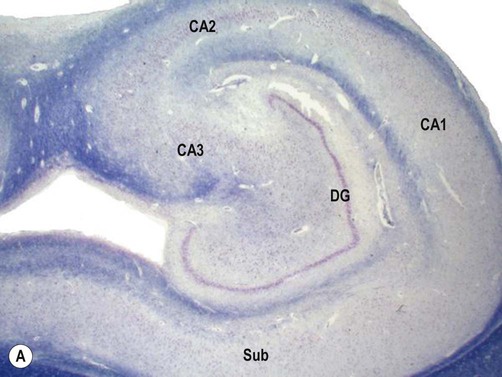

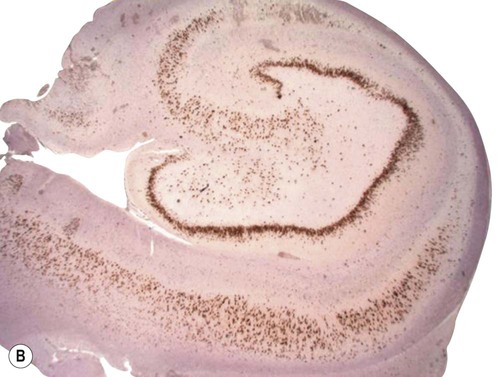

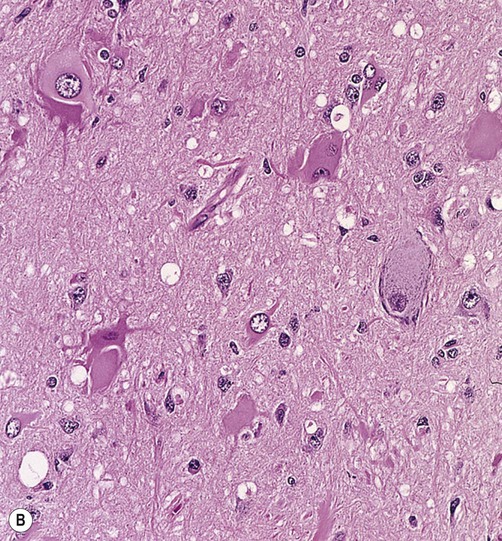

Examination of the specimen under the microscope shows marked loss of neurons in the pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampus, accompanied by glial scarring (Fig. 11.10). Neuronal loss is most pronounced in the CA1 subfield, a region that is selectively vulnerable to a range of pathological processes including hypoxia, ischaemia and excitotoxic injury (see Ch. 8). In severe cases there may be widespread loss of hippocampal neurons, but those within the CA2 subfield and dentate gyrus tend to be resistant.

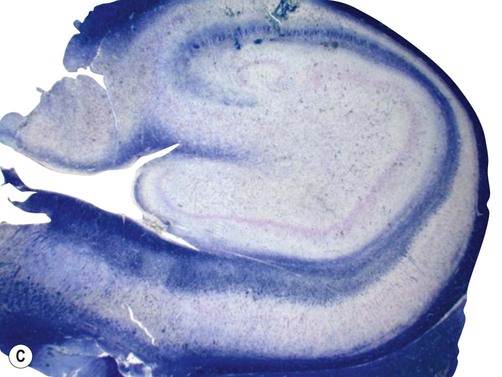

(A) Micrograph of a normal human hippocampus (stained with Luxol fast blue/cresyl violet) showing the main anatomical structures [DG = dentate gyrus; CA1-3 = subfields of Ammon’s horn; Sub = subiculum]; (B) Immunohistochemistry for the neuronal marker NeuN in a patient with hippocampal sclerosis showing neuronal loss in the CA1 subregion; (C) The same specimen stained with Luxol fast blue (a myelin stain) which shows collapse of the CA1 subfield; (D) Astrogliosis (glial ‘scarring’) in the same case, which is most obvious in CA1, demonstrated using antibody-labelling for the astrocytic marker GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein).

Malformations of cortical development

This is a group of neuronal migration disorders characterized by abnormal development of the cerebral cortex, termed cortical dysplasia. This accounts for approximately 20% of cases in epilepsy surgical specimens and is an important cause of pharmacoresistant partial seizures. There are several types (some of which are discussed in Clinical Box 11.8) but the most common form is focal cortical dysplasia.

Focal cortical dysplasia (FCD)

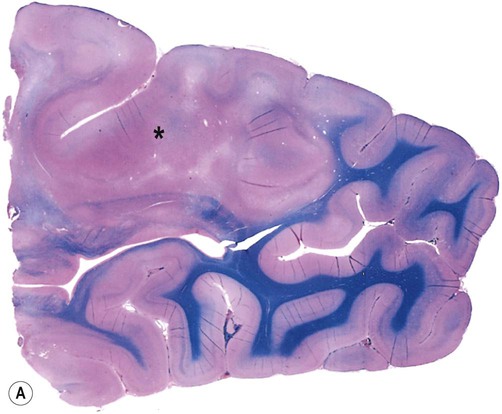

In this condition the affection region of the cerebral cortex is thickened and the junction with the subcortical white matter is blurred (Fig. 11.11A). The microscopic structure of the cortex is disturbed, with malorientated neurons and abnormal cell types (Fig. 11.11B):

(A) Brain specimen showing an area of abnormal cortical architecture (*) with blurring of the normally sharp boundary between the cerebral cortex (stained pink) and subcortical white matter (stained blue). This is a combined preparation using haematoxylin and eosin with Luxol fast blue; (B) Micrograph of FCD (routine haematoxylin and eosin staining) showing the disorganized cortical structure with abnormal (dysplastic) cells. The presence of balloon cells is best confirmed with immunohistochemistry (antibody labelling) by demonstrating large, swollen cells that express both neuronal and glial proteins. From Burger: Surgical Pathology of the Nervous System and its Coverings 4e (Churchill Livingstone 2002) with permission.

Balloon cells are large, rounded cells with intermediate features between neurons and glia; the presence of balloon cells is diagnostic of focal cortical dysplasia.

Balloon cells are large, rounded cells with intermediate features between neurons and glia; the presence of balloon cells is diagnostic of focal cortical dysplasia.

Dysplastic neurons have abnormal, bizarrely shaped cell bodies and dendrites, in addition to abnormal orientation and positioning within cortical laminae.

Dysplastic neurons have abnormal, bizarrely shaped cell bodies and dendrites, in addition to abnormal orientation and positioning within cortical laminae.

Giant neurons are large pyramidal cells with an otherwise normal morphology. They can be found throughout the dysplastic cortex.

Giant neurons are large pyramidal cells with an otherwise normal morphology. They can be found throughout the dysplastic cortex.

Epileptiform discharges have been obtained in electrode recordings from dysplastic cortex in human surgical specimens and appear to arise from abnormal neurons. Interestingly, the foci of dysplasia are indistinguishable from cortical ‘tubers’ in tuberous sclerosis (Clinical Box 11.9).

Glioneuronal tumours

Two tumours with a predilection for the mesial temporal lobe commonly cause drug-resistant focal epilepsy: dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumour (DNT) and ganglioglioma. These are both classified as ‘low-grade’ tumours, meaning that they are benign and slow-growing (see Ch. 5).

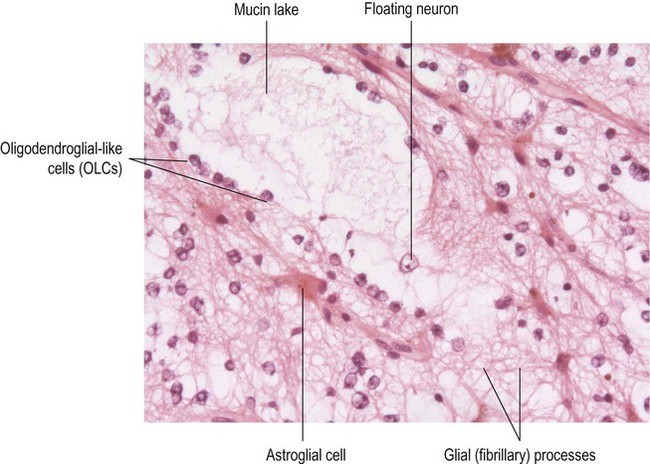

Microscopic examination shows a mixture of immature neurons and glial cells. In DNT, the main glial component consists of oligodendroglia-like cells (OLCs) (Fig. 11.13). The characteristic elements in ganglioglioma are ganglion cells, large neurons with rounded cell bodies and large nuclei. In 50% of cases binucleate ganglion cells can be found. Epileptiform discharges sometimes originate from abnormal neurons within the tumour itself and in other cases result from disturbance to the perilesional cortex, which is often removed together with the tumour.

Rows of cells with round nuclei (oligodendroglia-like cells or OLCs) can be seen lining up on either side of a large, mucin-filled lake. A ‘floating neuron’ with a large nucleus and prominent nucleolus is present with the mucin lake. Astrocytic cells (with a spidery appearance) can also be identified. This overall pattern is referred to as the ‘specific glioneuronal element’ and is diagnostic of DNT. (Routine haematoxylin and eosin staining.)

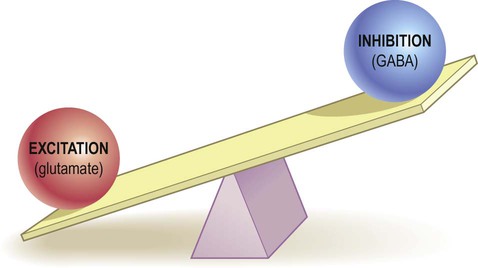

Partial seizure mechanisms

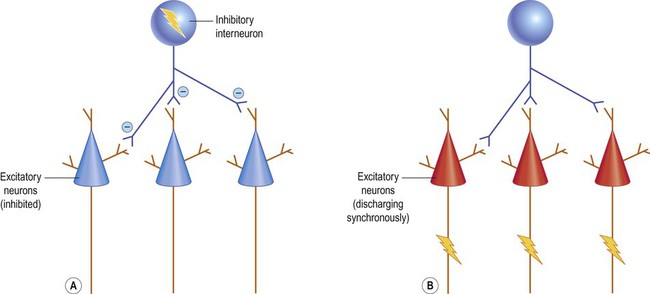

It was traditionally assumed that epilepsy resulted from a simple imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory influences in the brain (Fig. 11.14). It is now regarded as a network phenomenon that arises from abnormal synchronized discharges in large neuronal assemblies. Reseach (in animal models) has shown associated changes in connectivity, receptors and ion channels.

Animal models of epilepsy

Acute seizure models

Acute seizure models are used to simulate a range of epilepsies including generalized tonic-clonic, myoclonic and absence seizures. Prolonged stimulation (e.g. with pilocarpine) may induce status epilepticus (seizure activity lasting more than 30 minutes; see Clinical Box 11.10). This leads to changes in the medial temporal lobe that are similar to those seen in human temporal lobe epilepsy.

Chronic seizure models

A popular animal model of temporal lobe epilepsy is called kindling, which alludes to the process of starting a fire. In this method, an electrode is used to deliver a repetitive, low-frequency electrical stimulation to the medial temporal region of a rodent (e.g. within the amygdala or hippocampus; see Ch. 3). The current is not sufficient to cause a seizure, but sustained electrical stimulation over a period of time eventually leads to epileptiform discharges, together with a long-lasting susceptibility to further stimulation or even spontaneous seizures. It is thought that repetitive stimulation leads to abnormal recruitment of synaptic strengthening mechanisms (long-term potentiation or LTP) that are involved in learning and memory (see Ch. 7).

Electrical basis of epilepsy

Electrical recordings in animal models of epilepsy have identified abrupt shifts in the resting membrane potential of hippocampal neurons: the paroxysmal depolarization shift (PDS). An inward sodium current (mediated by voltage-gated ion channels) is followed by a prolonged, calcium-dependent depolarization. The PDS lasts ten times longer than a normal action potential and is associated with an intense burst of nerve impulses. It is terminated by calcium-sensitive potassium channels which repolarize the neuronal membrane. A prolonged period of after-hyperpolarization then follows (see Ch. 6). When a paroxysmal depolarization shift occurs simultaneously in several million cortical neurons it can be detected by scalp electrodes as an interictal spike. If the abnormal activity spreads over a large enough cortical area (more than a few centimetres in the human brain) it may develop into a seizure.

Pathophysiology of epilepsy

Alterations in connectivity

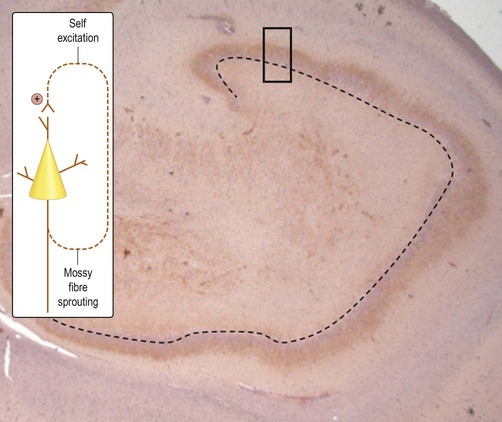

The axons of dentate granule cells (mossy fibres) normally extend into the hilum of the dentate gyrus and synapse on CA3 pyramidal neurons. In hippocampal sclerosis new axons arise from the granule cell layer in a process referred to as mossy fibre sprouting. Importantly, these new processes form aberrant, potentially self-excitatory connections within the granule cell layer that may promote seizure activity (Fig. 11.15). Abnormal connectivity of inhibitory interneurons might also contribute to epileptogenesis by encouraging synchronized bursting in groups of excitatory neurons (Fig. 11.16). This might help to explain why powerful inhibitory agents exacerbate some forms of epilepsy.

Changes in receptors and ion channels

A number of seizure-associated alterations have been observed at the neuronal cell and receptor level, including changes in the pattern of action potential firing. This has led to the concept of the epileptic (bursting) neuron. It appears that previously normal pyramidal neurons can change their behaviour during epileptogenesis to become ‘bursters’. This probably results from alterations within ion channels (or changes in their subunit composition) in the neuronal cell body. Synchronization can also be facilitated by the addition or strengthening of direct intercellular bridges between neurons called gap junctions (see Ch. 7).

Mechanism of absence seizures

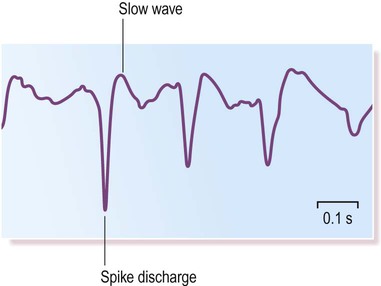

Unlike most forms of primary generalized epilepsy, the mechanism in absence seizures is well understood. It is due to derangement of a rhythmic pattern of oscillations that normally occurs between the cortex and thalamus during sleep. This creates the typical spike and wave discharge seen on the EEG (Fig. 11.17).

The abnormal discharges emerge from a normal background EEG trace at a typical frequency of 3 Hz (cycles per second).

The thalamic relay and sleep

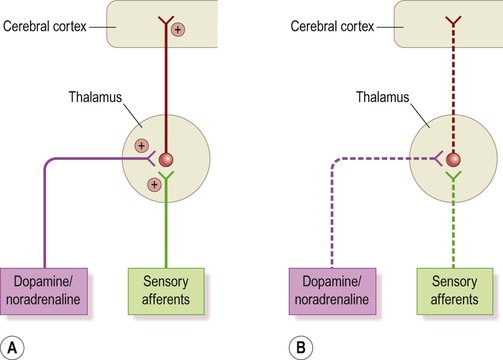

The thalamus acts as the ‘gateway’ to the cerebral cortex and contains specific thalamocortical relay nuclei for all sensory modalities apart from olfaction (see Ch. 3). Thalamocortical neurons projecting to the primary sensory areas of the cortex can be said to operate in two modes:

During wakefulness (Fig. 11.18A) they are tonically active, transmitting sensory information to the cortex. Excitatory noradrenergic and cholinergic projections from the diffuse neurochemical systems of the brain stem (see Ch. 1) contribute to their excitation.

During wakefulness (Fig. 11.18A) they are tonically active, transmitting sensory information to the cortex. Excitatory noradrenergic and cholinergic projections from the diffuse neurochemical systems of the brain stem (see Ch. 1) contribute to their excitation.

During sleep (Fig. 11.18B) thalamocortical sensory relay neurons are quiescent. This is due to reduced peripheral afferents (in a dark, quiet environment) and decreased activity in the diffuse projections from the brain stem.

During sleep (Fig. 11.18B) thalamocortical sensory relay neurons are quiescent. This is due to reduced peripheral afferents (in a dark, quiet environment) and decreased activity in the diffuse projections from the brain stem.

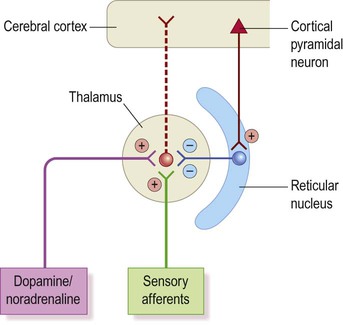

Sleep-associated hyperpolarization (inhibition) of thalamocortical neurons triggers a rhythmic pattern of oscillations between thalamus and cortex. This normally appears on the EEG as the sleep spindle, characterized by regular bursts of activity at a frequency of 12–14 Hz (cycles per second).

Origin of thalamic bursting

The sleep spindle depends upon a hyperpolarization-dependent cation channel which is expressed by thalamocortical neurons. The resting membrane potential for thalamocortical neurons is –60 mV and the reversal potential (see Ch. 6) for the hyperpolarization-dependent channel is –30 mV. Opening of the hyperpolarization-dependent channel therefore causes depolarization of thalamocortical cells (from –60 mV to –30 mV).

Origin of absences

Inhibition comes from the reticular nucleus of the thalamus which utilizes the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (Fig. 11.19). This nucleus appears to be stimulated by a hyperexcitable focus in the primary somatosensory cortex. In keeping with this idea, absence seizures can be triggered by cortical excitation in animal models, but only if thalamocortical connections are intact. This also explains why the calcium-channel antagonist ethosuximide is effective in the treatment of absence seizures.

Sudden death in epilepsy

Seizures are not generally life-threatening, provided that the airway is protected and that oxygenation is adequate. However, the risk of sudden death is 20–30 times higher than in non-epileptic controls and there is a well-recognized syndrome of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). This excludes deaths due to status epilepticus (see Clinical Box 11.10) and can only be diagnosed when the following criteria are met (see also Fig. 11.20):

SUDEP is most commonly seen in young adults with poorly controlled tonic-clonic seizures. It is more common in males and is associated with the use of multiple anti-epileptic drugs, poor compliance and alcohol misuse.

Cause of death

The mechanism of death in SUDEP is uncertain, but cardiorespiratory abnormalities are known to occur in temporal lobe epilepsy, including: cardiac dysrhythmias (disturbances of heart rhythm), apnoea (cessation of respiration) and hypoxaemia (low blood oxygen levels). In particular, there is evidence that seizures originating from the insula and amygdala (which have powerful visceral and autonomic projections; see Ch. 3) may lead to episodes of asystole (cardiac standstill).

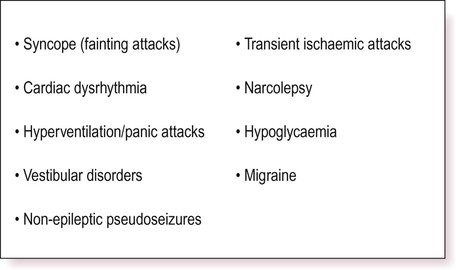

Psychological aspects

The differential diagnosis for epileptic seizures is wide (Fig. 11.21) and includes non-epileptic attacks of psychological origin (Clinical Box 11.11). There are a number of other psychological aspects to consider in patients with epilepsy, including a significant impact on leisure activities and occupation and an association with psychiatric illness.

Pseudoseizures are now more commonly referred to as psychogenic non-epileptic attacks.

Climbing, swimming and other outdoor pursuits may be extremely hazardous without proper supervision and in the UK and USA there are strict driving restrictions (Clinical Box 11.12). Occupational restrictions also apply for pilots, train drivers and members of the armed forces and emergency services.