31 Epilepsy

Epidemiology

Epilepsy does impact on an individual’s human rights, for example, access to health and life insurance is affected. A person who suffers from epilepsy may not be able to obtain a driving licence and it has an impact on the choice of career. In addition, legislation can impact on the life of individuals with epilepsy, for example, in some countries epilepsy may deter marriages. Legislation based on internationally accepted human rights standards can prevent discrimination and rights violations, improve access to health care services and raise quality of life (WHO, 2009). A global campaign has been established to raise awareness about epilepsy, provide information and highlight the need to improve care and reduce the disorder’s impact through public and private collaboration. This is supported through a partnership established between WHO, the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE).

Clinical manifestations

Partial or focal seizures

Secondarily generalised seizures

There have been recent proposals to revise the concepts, terminology and approaches for classifying seizures and forms of epilepsy (Berg et al., 2010). In this proposal, the so-called natural classes, for example, specific underlying cause, age at onset, associated seizure type; or pragmatic groupings, for example, epileptic encephalopathies, self-limited electroclinical syndromes, serve as the basis for classification.

Treatment

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2004a) issued guidance on the diagnosis and treatment of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. The guidance covered issues such as when a person with epilepsy should be referred to a specialist centre, the special considerations concerning the care and treatment of women with epilepsy and the management of people with learning disabilities. The key points of the guidance are summarised in Box 31.1.

Box 31.1 Key points on the diagnosis and management of epilepsy (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004a)

Treatment during seizures

Long-term treatment

Initiating treatment with an AED is a major event in the life of a person, and the diagnosis should be unequivocal. Treatment options must be considered with careful evaluation of all relevant factors, including the number and frequency of attacks, the presence of precipitating factors such as alcohol, drugs or flashing lights, and the presence of other medical conditions (Feely, 1999). Single seizures do not require treatment unless they are associated with a structural abnormality in the brain, a progressive brain disorder or there is a clearly abnormal EEG recording. If there are long intervals between seizures (over 2 years), there is a case for not starting treatment. If there are more than two attacks that are clearly associated with a precipitating factor, fever or alcohol for instance, then treatment may not be necessary.

General principles of treatment

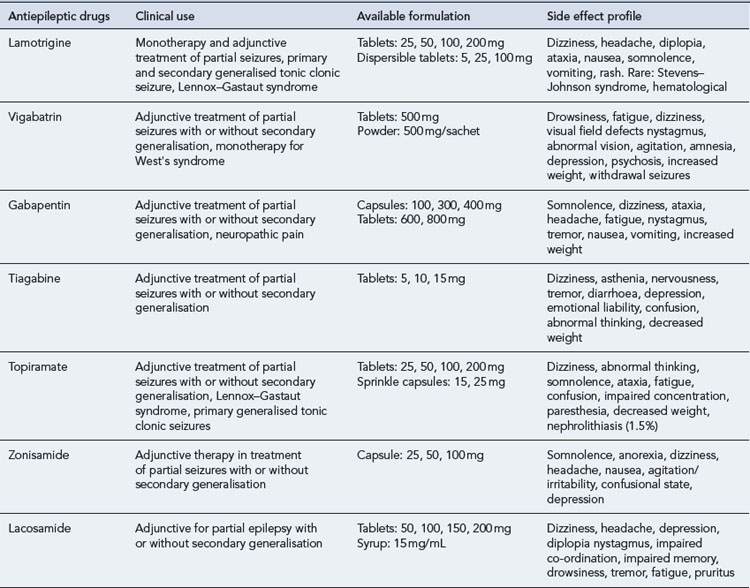

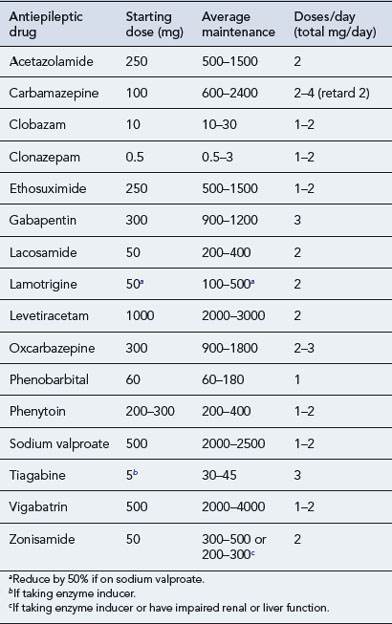

Therapy aims to control seizures using one drug, with the lowest possible dose that causes the fewest side effects possible. The established AEDs, carbamazepine, ethosuximide and sodium valproate, are still important parts of the antiepileptic armamentarium. Acetazolamide, clobazam, clonazepam, phenobarbital phenytoin and primidone are also still used. In the last two decades, new AEDs such as vigabatrin, lamotrigine, gabapentin, topiramate, tiagabine, oxcarbazepine, levetiracetam, pregabalin, zonisamide, lacosamide and eslicarbazepine acetate have been introduced. The choice of drugs depends largely on the seizure type, and so correct diagnosis and classification are essential. Table 31.1 lists the main indications for the more commonly used AEDs, and Table 31.2 summarises the clinical use of the newer AEDs.

| Seizure type | First-linetreatment | Second-line treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Partial seizures | ||

| Carbamazepine | Topiramate | |

| Lamotrigine | Valproate | |

| Oxcarbazepine | Clobazam | |

| Levetiracetam | Zonisamide | |

| Pregabalin | ||

| Phenytoin | ||

| Gabapentin | ||

| Lacosamide | ||

| Eslicarbazepine | ||

| Generalised seizures | ||

| Tonic clonic | Valproate sodium | Lamotrigine |

| Tonic | Carbamazepine | Clobazam |

| Clonic | Lamotrigine | Phenobarbital |

| Absence | Ethosuximide | Clonazepam |

| Sodium valproate | Lamotrigine | |

| Atypical absences | Sodium valproate | |

| Atonic | Clonazepam | Lamotrigine |

| Clobazam | Carbamazepine | |

| Phenytoin | ||

| Acetazolamide | ||

| Topiramate | ||

| Myoclonic | Sodium valproate | Levetiracetam |

| Clonazepam | Acetazolamide | |

| Topiramate | ||

Newer AEDs

There is no evidence that the newer AEDs are more effective than the established drugs, although it could be argued that they might be better tolerated. The chronic side effect profile of the new AEDs has not yet been fully established and this is the main reason why use should be reserved for those cases where benefit outweighs risk. Guidance has been issued that covers the use of the newer AEDs in adults (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004b):

The guidance for adults was followed up by advice for use of the newer AEDs in children (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004c). This advice reflected that issued for adults and included:

A third set of national guidance was issued on the diagnoses and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004a). A recent report on the implementation of this guidance (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009) revealed:

Monitoring antiepileptic therapy

Drug development and action

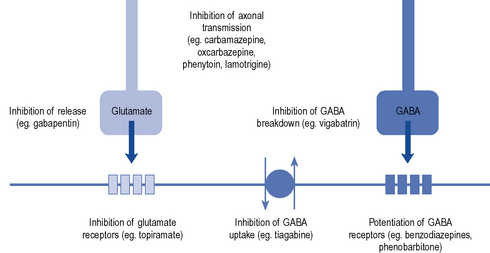

Established AEDs such as phenytoin, phenobarbital, sodium valproate, carbamazepine, ethosuximide, clonazepam and diazepam are effective but have poor side effect profiles, are involved in many interactions and have complex pharmacokinetics. Over the past 10–15 years, there has been renewed interest in the development of new AEDs, based on a better understanding of excitatory and inhibitory pathways in the brain. The main mechanisms of current drugs are thought to involve enhancement of the inhibitory GABA-ergic system, for example, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, tiagabine, vigabatrin or use-dependent blockers of sodium channels, for example, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine and phenytoin (Fig. 31.1).

New drugs include lamotrigine, pregabalin, levetiracetam, topiramate, felbamate, lacosamide, oxcarbazepine, eslicarbazepine and zonisamide. Unlike most of the older agents, vigabatrin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, lacosamide, gabapentin, pregabalin and zonisamide are devoid of clinically significant enzyme-inhibiting or enzyme-inducing properties. Oral contraceptives may increase the metabolism of lamotrigine and topiramate, and oxcarbazepine may induce cytochrome P450 CYP3A4 which is responsible for the metabolism of oral contraceptives (Sabers and Gram, 2000).

AED profiles

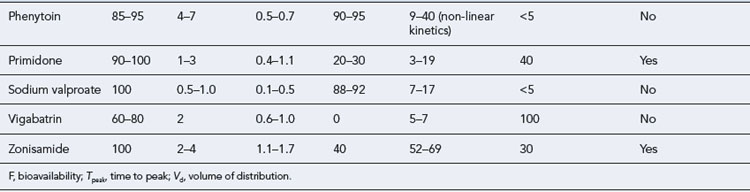

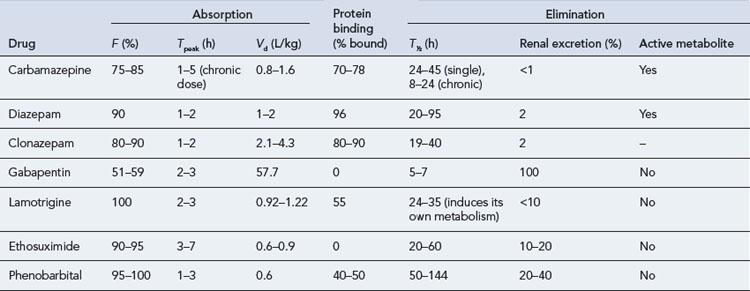

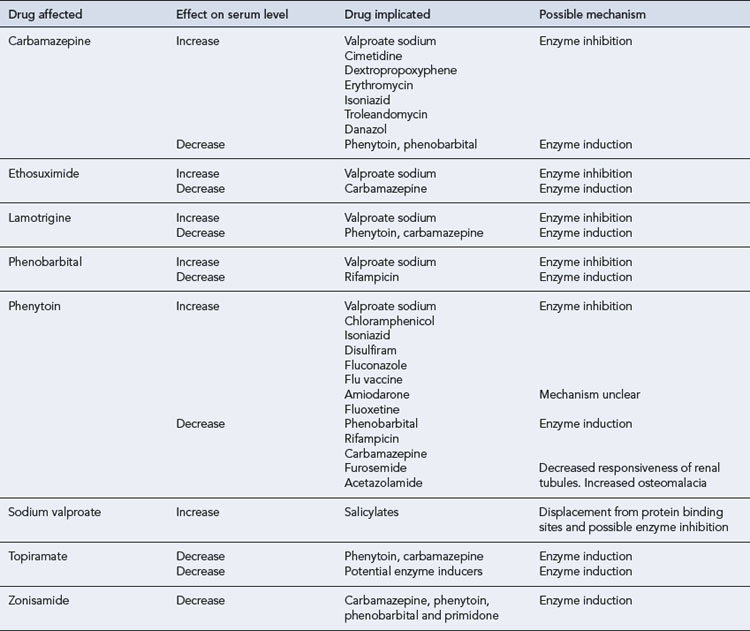

The maintenance doses for the more widely used AEDs are given in Table 31.3, while their pharmacokinetic profile is presented in Table 31.4. Drug interactions are summarised in Table 31.5, and common side effects in Table 31.6.

| Drug | Dose related (predictable) | Non-dose related (idiosyncratic) |

|---|---|---|

| Carbamazepine | Diplopia, drowsiness, headache, nausea, orofacial dyskinesia, arrhythmias | Photosensitivity, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, agranulocytosis, aplastic anaemia, hepatotoxicity |

| Clonazepam | Fatigue, drowsiness, ataxia | Rash, thrombocytopenia |

| Ethosuximide | Nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, headache, lethargy | Rash, erythema multiforme, Stevens–Johnson syndrome |

| Gabapentin | Drowsiness, diplopia, ataxia, headache | Not reported |

| Lacosamide | Nausea, vomiting, dizziness, headache, drowsiness, depression, diplopia (double vision), impaired memory, impaired coordination, tremor, fatigue (tiredness), asthenia (muscle weakness), pruritus (itching). | Not reported |

| Lamotrigine | Headaches, drowsiness, diplopia, ataxia | Liver failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| Levetiracetam | Dizziness, drowsiness, irritability, behavioural problems, insomnia, ataxia (unsteadiness), tremor, headache, nausea | Not reported |

| Oxcarbazepine | Diplopia (double vision), ataxia (unsteadiness), headache, nausea, confusion and vomiting | Skin rash |

| Phenobarbital | Fatigue, listlessness, depression, poor memory, impotence | Maculopapular rash, exfoliation, hepatotoxicity hypocalcaemia, osteomalacia, folate deficiency |

| Phenytoin | Ataxia, nystagmus, drowsiness, gingival hyperplasia, hirsutism, diplopia, asterixis, orofacial dyskinesia, folate deficiency | Blood dyscrasias, rash, Dupuytren’s contracture, hepatotoxicity |

| Sodium valproate | Dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, hair loss, anorexia, drowsiness | Acute pancreatitis, aplastic anaemia, thrombocytopenia, hepatotoxicity |

| Tigabine | Dizziness, fatigue (tiredness), nervousness, tremor, concentration difficulties, depression of mood, agitation | |

| Topiramate | Dizziness, drowsiness, nervousness, fatigue, weight loss | Not reported |

| Vigabatrin | Drowsiness, dizziness, weight gain | Behavioural disturbances, severe psychosis |

| Zonisamide | Ataxia, dizziness, somnolence, anorexia | Hypersensitivity, weight decrease, rash, gastro-intestinal problems |

Carbamazepine

Carbamazepine exhibits autoinduction, that is, induces its own metabolism as well as inducing the metabolism of other drugs. It should, therefore, be introduced at low dosage and this should be steadily increased over a period of a month. The target serum concentration therapeutic range is 4–12 μcg/mL. In addition, a number of clinically important pharmacokinetic interactions may occur, and caution should be exercised when co-medication is instituted (see Table 31.5). For patients requiring higher doses, the slow-release preparation of carbamazepine has distinct advantages, allowing twice-daily ingestion and avoiding high peak serum concentrations. A ‘chewtab’ formulation is also available and pharmacokinetic studies have shown that it performs well even if inadvertently swallowed whole. Carbamazepine retard offers paediatric patients in particular a dosage form that reduces fluctuations in the peak to trough serum levels and hence allows a twice-daily regimen, which can assist compliance.

Phenobarbital

Phenobarbital, a barbiturate, may be used for the treatment of tonic clonic, tonic and partial seizures. It may also be used in other seizure types. Its antiepileptic efficacy is similar to that of phenytoin or carbamazepine. Adverse effects on cognitive function, the propensity to produce tolerance and the risk of serious seizure exacerbation on withdrawal make it an unattractive option, and it should be used only as a last resort. In addition to cognitive effects, barbiturates may cause skin rashes, ataxia, folate deficiency, osteomalacia, behavioural disturbances (particularly in children) and an increased risk of connective tissue disorders such as Dupuytren’s contracture and frozen shoulder. Phenobarbital is a potent enzyme inducer and is implicated in several clinically important drug interactions (see Table 31.5).

Phenytoin

In current practice, phenytoin is now a second-line drug for partial seizures, tonic clonic seizures as well atonic seizures and atypical absences. It is not effective in typical generalised absences and myoclonic seizures. Tolerance to its antiepileptic action does not usually occur. Phenytoin has non-linear kinetics and a low therapeutic index, and in some patients frequent drug serum level measurements may be necessary. Drug interactions (see Table 31.5) are common as phenytoin metabolism is very susceptible to inhibition by some drugs, while it may enhance the metabolism of others. Caution should be exercised when other medication is introduced or withdrawn.

Zonisamide

Side effects of zonisamide include dizziness, drowsiness, headaches, hyporexia, nausea and vomiting, weight loss, skin rashes, irritability, impaired concentration and fatigue. These are mostly transient and seem to be related to the dose and rate of titration. Nephrolithiasis has also been reported, particularly in caucasians. It is not recommended for women of child-bearing age as there are issues about its teratogenic potential (Table 31.7).

| Problem | Comment |

|---|---|

| Hepatic enzyme induction | Enzyme induction occurs with carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, primidone and topiramate |

| Interactions occur with a large number of drugs including oral contraceptives | |

| Use of progesterone-only contraceptives with enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drug | Best avoided. If no acceptable alternative, patient should take at least double usual dose of progesterone-only pill |

| Use of combined oral contraceptive with enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drug | Preparations containing 50 μcg of oestrogen should be used |

| Continuation of antiepileptic drug during pregnancy | Ideally review before attempting pregnancy to determine if reducing or discontinuing treatment is possible |

| Use of phenytoin as monotherapy | Less frequently considered first-line monotherapy due to poor side effect profile, narrow therapeutic index and saturation pharmacokinetics |

| Prescribing of branded antiepileptic drugs | Debate continues about whether significant differences exist between generic and branded antiepileptic drugs |

Evidence for clinical use of newer drugs

The evidence for the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of seven new AEDs (gabapentin, lamotrigine, topiramate, tiagabine, oxcarbazepine, levetiracetam and zonisamide) in the treatment of children and adults with refractory partial and generalised epilepsies was assessed by French et al. (2004). All drugs demonstrated efficacy as add-on therapy in patients with refractory partial epilepsy. The relative efficacy of the various agents could not, however, be determined due to the differing populations and dose ranges employed in the various studies. The analysis did, however, show that for all drugs, efficacy and side effects increased with increasing dose. A slower titration of dosage improved tolerability and hence the guidance remains to start with a low dose and increase slowly until side effects occur. For efficacy it appears useful to push to maximal tolerated dose.

Wilby et al. (2005) evaluated the clinical effectiveness, tolerability and cost-effectiveness of gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, tiagabine, topiramate and vigabatrin for epilepsy in adults. They included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews for the newer AEDs when used in the treatment of adults with newly diagnosed or refractory epilepsy and relevant comparator studies which employed older AEDs, other newer AEDs and placebo. The overall findings revealed the following:

Berg A.T., Berkovic S.F., Brodie M.J., et al. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE commission on classification and terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia. 2010;51:676-685.

Duncan J.S., Sander J.W., Sisodiya S.M., et al. Adult epilepsy. Lancet. 2006;367:1087-1100.

Feely M. Drug treatment of epilepsy. Br. Med. J.. 1999;318:106-109.

French J.A., Kanner A.M., Bautista J., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs, II: treatment of refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2004;45:410-423.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The epilepsies: the diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care, Clinical Guideline 20. London: NICE. 2004. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=CG020&c=cns

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. New drugs for epilepsy in adults, Technology Appraisal 76. London: NICE. 2004. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/download.aspx?o=ta076guidance

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Newer drugs for epilepsy in children, Technology Appraisal 76. London: NICE. 2004. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=ta079guidance

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Implementation uptake report: the epilepsies, the diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. London: NICE; 2009. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/media/250/28/ImpUptakeReportCG20.pdf

Sabers A., Gram L. Newer anticonvulsants: comparative review of drug interactions and adverse effects. Drugs. 2000;60:23-33.

WHO. Epilepsy, Key Facts. Fact Sheet Number 999. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs999/en/, 2009.

Wilby J., Kainth A., Hawkins N., et al. Clinical effectiveness, tolerability and cost-effectiveness of newer drugs for epilepsy in adults: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment. 9(15), 2005. Available at: http://www.hta.ac.uk/1304

Brodie M.J., Kwan P. Epilepsy in elderly people. Br. Med. J.. 2005;331:1317-1322.

Nair D.R., Nair R., O’Dyer R., editors. Epilepsy. Oxford: Clinical Publishing, 2010.

Shorvon S.D., editor. Epilepsy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Takahashi K., editor. Epilepsy Research Progress. New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc, 2008.

Tebb Z., Tobias J.D. New anticonvulsants – new adverse effects. South Med. J.. 2006;99:375-379.