CHAPTER 136 Epidermoid, Dermoid, and Neurenteric Cysts

Recent developments in understanding the embryogenesis of complex dysraphic malformations suggest that the three central nervous system (CNS) entities epidermoid, dermoid, and neurenteric cysts all reflect a problem at the gastrulation stage of development and consist of primary disruption of tissues derived from one or more of the three germ cell layers.1–3 Thus, dermoid and epidermoid cysts, as well as dermal sinus tracts, reflect an abnormality of surface ectoderm, and neurenteric cysts are a type of endodermal malformation. All three disorders are frequently associated with one or more of the mesodermal malformations, particularly those involving the vertebrae (e.g., hemivertebrae, absent vertebrae, fused vertebrae, butterfly vertebrae, midline bony spurs).

Epidermoid Cysts

Epidermoid cysts or tumors are benign lesions that may arise in the spine or intracranially. They may be intradural (usually extra-axial) or extradural (usually arising in the diploic space of the calvaria). Intracranial epidermoid cysts account for 0.2% to 1.8% of all intracranial tumors.4,5 They generally occur in the cerebellopontine angle or in the parasellar cisterns.6–8 Most intraspinal epidermoid cysts are subdural and extramedullary, but they can rarely develop in the intramedullary compartment.9,10 In 1936, Love and Kernohan first described epidermoid and dermoid cysts as congenital epithelial tumors.11 However, it has been widely held that these tumors derive from ectopic inclusions of epithelial cells during neural tube closure.12 More recently, Dias and Walker explained their cause as primarily being a gastrulation dysembryogenesis,3 with secondary disruption of neural tube closure during the third to fifth week of gestation.13 Epidermoid and dermoid cysts represent malformations of surface ectoderm (as opposed to neuroectoderm) in this schema.

Clinical Findings

Epidermoid tumors have been reported in patients from infancy to adulthood and have been incidental findings at autopsy.11 They may be cranial or spinal in location. The average age at detection is 40 years.4 The tumors usually grow linearly, similar to normal skin, and thus have an insidious onset.14 The symptoms and signs are variable and depend on tumor location. Extradural lesions are often manifested as a local mass, with or without headache.12 Intradural tumors are more likely to be associated with headache (because of the common parasellar location), visual disturbance, and to a lesser extent, hypothalamic alterations. Tumors in the middle fossa grow quite insidiously and are often asymptomatic, whereas those in the cerebellopontine angle may cause ataxia, dizziness, or local cranial nerve deficits.4 Twenty years of trigeminal numbness was the initial complaint in a patient with a large middle fossa–petrous apex–Meckel’s cave interdural (between the dural leaves) epidermoid.15 A picture of acute meningitis may indicate epidermoid cyst rupture. Spinal epidermoid tumors are frequently associated with vertebral anomalies.3,11

In their classic 1936 paper on epidermoid and dermoid tumors, Love and Kernohan described 15 patients, 10 of whom had epidermoid tumors.11 Seven of these tumors were intradural, and 3 were extradural. Almost 60 years later, Gormley and colleagues reported their experience with 32 tumors, 22 of which were epidermoids (16 intradural and 6 extradural).12 The initial symptoms and signs in both series were amazingly similar. The duration of symptoms is long for epidermoid tumors, an average of 16 years in the series of Love and Kernohan.11 Recently, Akar and coauthors reported their experience with 28 cases of intracranial epidermoid tumor, 17 of which were in the cerebellopontine angle, 2 in the fourth ventricle, 1 in the cisterna magna, 4 in the sylvian fissure, 2 in the occipital lobe, 1 in the lateral ventricle, and 1 in the intradiploic space.4 The median duration of symptoms was 4.6 years.

Imaging

With the advent of CT, intradural epidermoid tumors could be more accurately diagnosed. Typical CT findings consist of a homogeneous nonenhancing hypodense lesion in the subarachnoid space without surrounding edema. The differential diagnosis includes arachnoid cyst, Rathke’s cleft cyst, craniopharyngioma, and other cystic tumors, with arachnoid cysts being the most problematic. Careful evaluation of Hounsfield units may show the lesion to have more fat density than cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) density. Epidermoid tumors more often extend into the subarachnoid space and enlarge it, unlike arachnoid cysts, which cause a more focal mass effect. Occasionally, epidermoids are seen as high-density masses (“white epidermoids”) on CT images, which can make diagnosis difficult.2,5

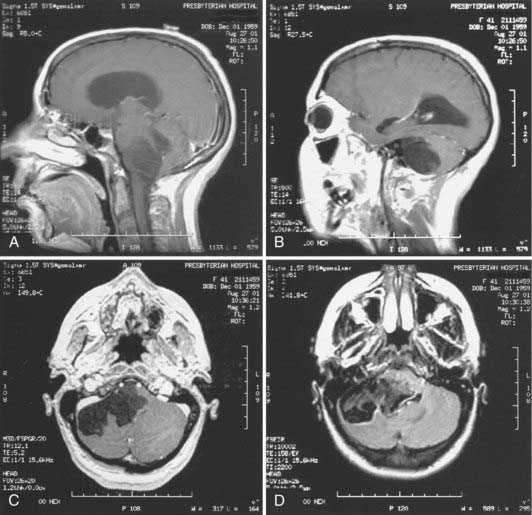

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is now the tool of choice for diagnosing these lesions. Signal intensity patterns are variable, ranging from hypointense to hyperintense, and the tumors are frequently multiloculated. Typically, the tumor signal is heterogeneous and most often shows hypointensity on T1-weighted images and hyperintensity on T2-weighted images.2,7 There may be a rim of high signal intensity visible on proton density studies; some tumors show rim enhancement with gadolinium administration (Fig. 136-1). The differential diagnosis again includes the cystic entities described earlier. It is difficult to distinguish epidermoids from arachnoid cysts on standard and spin echo MRI pulse sequences, but diffusion-weighted (DW), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), constructive interference in the steady state, and fast imaging with steady-state precession studies can often differentiate between epidermoid tumors and the CSF within arachnoid cysts.16 There is usually no edema of the surrounding parenchyma, and hydrocephalus is rare, even in the setting of large tumors and brain displacement. In a radiographic series of 23 intracranial epidermoids, Kallmes and coauthors reported 14 tumors in the cerebellopontine angle, 6 (43%) of which extended into Meckel’s cave.17 Hakyemez and colleagues conducted a prospective radiologic study comparing DW with spin echo and FLAIR sequences in the evaluation of 15 patients with intracranial epidermoid cysts.16 They found that FLAIR sequencing was superior to the use of conventional MRI in demonstrating the epidermoid cysts and that DW imaging was superior to other types of MRI sequencing in delineating the borders of the epidermoid cysts.

Treatment

Symptomatic patients benefit from surgery, but it is often technically difficult because of tumor adhesions insinuating themselves among adjacent structures. The tumor is well demarcated, with a smooth, hypovascular capsule. The cyst contains characteristic pearly flakes. Current recommendations for the surgical approach are similar to those promulgated by Love and Kernohan in 1936,11 including primary intracapsular debulking and subsequent removal of the capsule. The surgical ultrasonic aspirator is extremely useful in the operative management of these tumors. Fragments of capsule adherent to important structures are left when necessary to avoid neural or vascular injury. Although subtotal resection increases the risk for recurrence, the slow growth of epidermoid cysts makes this less problematic. The capsule should not be removed from intramedullary cysts because of the risk of causing neurological deficits.10

Much has been written and said about the risk for chemical meningitis associated with intraoperative spillage of cyst contents or preoperative cyst rupture. This has also been reported as a radiographic finding of small fat globules in the subarachnoid and intraventricular spaces.4 Steroid administration is useful in the treatment of meningitis, but hydrocephalus may ensue and require shunting. At this time, there is no established role for radiotherapy or chemotherapy in the treatment of residual or recurrent epidermoid cysts.

Pathology

Epidermoid cysts are benign and consist of a thin capsule of stratified, keratinized squamous epithelium. The cyst contains an accumulation of desquamated epithelial cells, keratin, and cholesterol. Malignant transformation in these tumors is rare, but squamous cell carcinoma has been reported to arise from an epidermoid cyst.18 Fifteen cases of leptomeningeal dissemination of squamous cell carcinoma arising in an epidermoid cyst have been reported, only four of which demonstrated malignant cells within the CSF.19 A malignant melanoma has also been reported in a temporal lobe epidermoid.14 Immunohistochemical staining for the carbohydrate antigen CA19-9 has been positive in intracranial epidermoids.20 Positive staining for CA19-9 occurred in epithelial cells in the cyst wall in two of four patients with intracranial epidermoids, as well as in the subepithelial collagenous tissue and keratinous tissue.20 This tumor marker, originally developed as a colon cancer antigen, is also detected in the serum of patients with epidermoid tumors. Takeshita and coworkers reported one patient who underwent incomplete tumor resection and whose postoperative CA19-9 serum levels remained elevated but lower than preoperative levels.20 Thus, serum antigen levels can be used to evaluate patients for tumor recurrence or progression.

Dermoid Cysts

Dermoid cysts share many characteristics with epidermoid cysts. They are also clinically and biologically benign, with the main problem at initial evaluation being related to mass effect on neural structures in a tight space (intracranial or spinal). They represent a developmental malformation, with the defect in gastrulation affecting the surface ectoderm and causing a secondary disruption of neural tube closure.3 An interesting case report of monozygotic twins—one with a cerebellar dermoid tumor and an occipital dermal sinus tract and the other with an occipital meningocele and cerebellar aplasia—supports the theory that the malformation occurs at the gastrulation phase with secondary dysraphism.21 Epidermoid cysts contain epithelial cell debris and keratin, whereas dermoids contain elements of the dermis, such as hair and hair follicles and apocrine, sebaceous, or sweat glands. Intracranial dermoids are rare congenital lesions that account for 0.04% to 0.6% of all intracranial tumors. They tend to occur at the midline and, when extradural, may arise at the anterior fontanelle.1,21

Clinical Findings

Patients with dermoid cysts are generally seen at a younger age than those with epidermoids. Gormley and coworkers noted an average age at diagnosis of 15 years for dermoid cysts versus 35 years for epidermoids.12 In the study by Love and Kernohan, the duration of symptoms averaged 8.5 years in patients with dermoid tumors and 16 years in those with epidermoid tumors.11 Their 15-patient series consisted of five dermoid tumors: three intracranial-intradural, one spinal-intramedullary, and one calvarial-extradural. Dermoid cysts are usually found at the midline. As with epidermoid cysts, there is a female preponderance, and patients may initially be seen with local neural deficits, headache, or meningitis.12 Dermoid tumors have been reported in association with Klippel-Feil syndrome.22

Imaging

Just as with epidermoid cysts, CT and MRI can delineate many characteristic features. As seen on CT, the lesions are usually hypodense and avascular and do not exhibit contrast enhancement. The MRI characteristics of dermoids are also similar to those of epidermoids, with perhaps even more signal heterogeneity. Relaxation time on these images may be variable, depending on the fat content of the lesion. The tumors usually show high signal levels on both T1- and T2-weighted images.2 Because dermoid tumors are generally more solid than epidermoid tumors, they are less likely to grow between neurovascular structures and tend to demonstrate more of a local mass effect. Surrounding parenchymal edema is lacking. Rare cases of dermoid cysts showing contrast enhancement and even an enhancing mural nodule have been reported.23 Although it was previously thought to be uniformly fatal, dermoid cyst rupture can result in different patterns of distribution of the spilled contents, as visualized on MRI.24 Most commonly, fat droplets may be seen throughout the subarachnoid or intraventricular space. Another pattern is that of localized dissemination in the sulci causing widening, perhaps contained by pia or inflammatory tissue. Spinal dermoid cysts have been manifested as hydrocephalus secondary to CSF obstruction by fat droplets.25 An extradural cranial lesion shows the typical bony erosive changes seen with epidermoids.

Treatment

Surgical extirpation is the treatment of choice of dermoids and may be somewhat less problematic than removal of epidermoid tumors because of the firmer consistency of dermoids. Complete excision decreases the risk for both postoperative chemical meningitis and tumor recurrence. Tumor recurrence has been reported with both cranial and spinal dermoids.25 Although surgical resection of recurrent tumors may be more difficult, this should not influence the decision to reoperate. The surgeon must be cognizant of adherence of the tumor capsule to vascular and neural structures, damage to which can be devastating. This consideration may dictate a more conservative surgical approach. As might be predicted, surgical treatment of recurrent cysts remains controversial. There is no current role for radiotherapy or chemotherapy in the treatment of these tumors.

Pathology

Histopathologically, dermoid cysts are benign and demonstrate both dermal and epidermal elements. The epithelial cell lining may be less differentiated in dermoids than in epidermoids.14 Serum CA19-9 levels were found to be elevated in two of three patients with dermoid cysts, and the levels tended to be higher than in patients with epidermoid cysts. In one patient who had incomplete resection of a dermoid tumor, antigen levels remained high postoperatively.20

Neurenteric Cysts

Neurenteric cysts, also known as enterogenous cysts, neuroepithelial cysts, gastrocytomas, and foregut cysts, are rare developmental malformations that occur intracranially or in the spinal canal. They represent approximately 0.7% to 1.3% of all spinal cord tumors26 and 16% of cysts in the CNS.27 They are usually extramedullary and arise in the pontomedullary region, cerebellopontine angle, parasellar area, and craniocervical junction and along the spinal axis; intramedullary lesions have been reported both intracranially and in the spine.26,28,29

These cysts develop as early as embryonic day 16 to 17. They have been considered part of the split notochord syndrome or split cord malformation.30 Dias and Walker classified them as one of the endodermal malformations arising as a result of abnormal gastrulation.3 After this embryologic phase, a tube of mesoderm condenses to form the notochord. The neurenteric canal, a normally transient communication between the endoderm and ectoderm through the notochord, is also seen at this stage. By the third embryonic week, this neurenteric canal closes, and the notochord separates from the primitive gut.31 A persistent embryologic communication between the endoderm and ectoderm results in neurenteric fistulas or cysts.32,33 Most are ventral in the CNS and extra-axial. Spinal neurenteric cysts are almost pathognomonically associated with vertebral anomalies such as cleft vertebrae, hemivertebrae, spina bifida, absent or fused vertebrae, or diastematomyelia.26,29 Spinal neurenteric cysts, particularly in the low cervical or high thoracic region, are more common than intracranial neurenteric cysts.28 Up to 5% of patients with Klippel-Feil syndrome and vertebral fusion abnormalities may have neurenteric cysts and fistulas.34

Clinical Findings

Neurenteric cysts may develop prenatally up through adulthood.29 In general, there is no definite predominance of these lesions in either sex, but spinal neurenteric cysts are seen more often in males, whereas 60% of intracranial cysts have been reported in females.27,35 Patients have symptoms and signs relative to the location of the lesion in the CNS, usually as a result of compression of the adjacent spinal cord. In general, the course of the disease in adults is slow and insidious; progression is more rapid in children. When a fistula persists, patients may initially be seen with recurrent meningitis.34 Unusual manifestations have been reported, such as acute onset of neurological deficits, episodic neurological deficits with recovery between the episodes, aseptic (chemical) meningitis, chronic pyrexia, and infantile paraplegia.26,29

Imaging

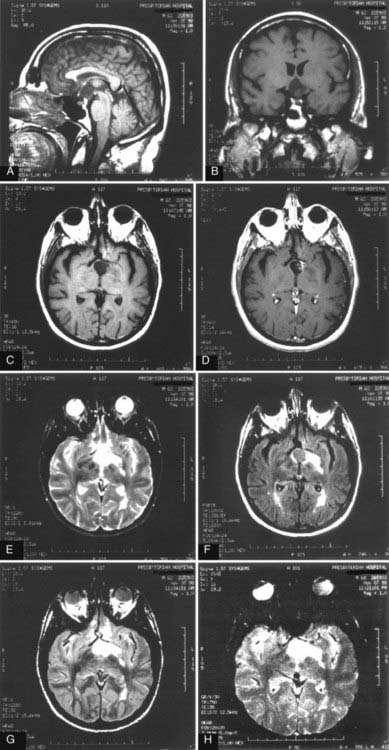

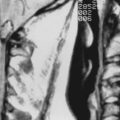

MRI is currently the best choice for evaluation of both spinal and intracranial cysts. The cysts often parallel the signal intensity of CSF seen on T1- and T2-weighted images. Mixed signal intensity has been described (Fig. 136-2). There have been reports of T1 signal changes in these tumors, probably resulting from changes in protein concentration or hemorrhage.26,36 Most cysts do not show enhancement after the administration of gadolinium contrast material, but some variable wall enhancement may be present.37 The cysts have a tendency to insinuate themselves between surrounding structures. Intracranial neurenteric cysts have been located primarily in the posterior fossa, midline fourth ventricular area, or cerebellopontine angle, although there have also been reports of parasellar cysts.2 Spinal neurenteric cysts are seen ventral or dorsal to the spinal cord and are rarely intramedullary.26,29 The radiographic differential diagnosis includes epidermoid and dermoid cysts, arachnoidal and ependymal cysts, colloid cysts, Rathke’s cleft cysts, and other cystic tumors.2

Treatment

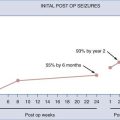

Treatment of these slow-growing lesions is primarily surgical. The goal is complete resection, although this is not always feasible given the difficulty of completely removing the cyst wall at locations where it adheres to adjacent structures. Descriptions of the cyst fluid have varied, including clear and colorless, milky, yellowish, gelatinous, xanthochromic, and blackish and viscous.26,29 Attempts to remove the capsule of intramedullary cysts usually result in increased neurological deficits.26,30 Other modalities of treatment, such as simple cyst aspiration, cyst wall marsupialization, or creation of a cyst-subarachnoid shunt, are considered in difficult cases.26 Aseptic meningitis as a consequence of these latter maneuvers has not been the problem one might expect. Cyst recurrence has been reported 4 to 14 years after surgery in cases in which macroscopically complete removal was achieved.26 Recurrence after incomplete cyst wall removal is variable as well. Conventional radiotherapy for residual tumor is not likely to be effective given the benign and cystic nature of the tissue. Whether there may be some role for radiosurgery in the treatment of residual neurenteric cysts remains to be seen. Chemotherapy has not been used in the treatment of these tumors.

Pathology

Histologically, neurenteric cysts are benign tumors. The cyst wall is composed of well-differentiated cuboidal, columnar, or ciliated epithelium, with or without goblet cells or microvilli.2,26 Mucin-containing cells show a positive reaction with periodic acid–Schiff stain and are seen in 75% to 80% of specimens.26,29 The epithelium may resemble the intestinal or respiratory type, and there may be smooth muscle in the underlying fibrovascular tissue.26,29 Immunohistochemical staining is positive for cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen and negative for vimentin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and S-100.28,30 The cells also often test positive for carcinoembryonic antigen.27,35

It is important to differentiate between neurenteric and ependymal cysts. The presence of an underlying basement membrane or collagenous tissue separating the epithelial layer from neuroglial tissue is characteristic of neurenteric cysts.30 Lack of immunoreactivity to glial fibrillary acidic protein, S-100, neuron-specific enolase, and vimentin allows exclusion of arachnoidal or ependymal cysts.28,35 Mittler and McComb reported a patient with an intramedullary thoracic neurenteric cyst and an arachnoid cyst directly subjacent in the ventral extra-axial space.38

Malignant transformation of these tumors is rare. Wang and associates reported a patient with a neurenteric cyst that had focal malignant features.28 In addition, Ho and coworkers described a patient who had a well-differentiated papillary adenocarcinoma within a supratentorial neurenteric cyst.39

Conclusion

Epidermoid and dermoid tumors were described in a classic paper more than 70 years ago,11 and more recent series of patients have confirmed the clinical and histopathologic features.4,6,12 Dermoid cysts generally arise at an earlier age than epidermoids and have a shorter duration of symptoms. Dermoids are denser tumors than epidermoids and have a more focal mass effect. This may explain why patients with dermoids are initially seen at a younger age. Radiographic evaluation of epidermoids and dermoids has improved significantly since the advent of MRI, but there are no pathognomonic radiographic features for either of these tumors. Surgical extirpation is the treatment of choice, with the goal being complete resection. However, because both these entities can grow between and around neural and vascular structures, the risk for operative damage can be high and preclude complete resection. Pathologic study of these tumors is usually straightforward. The tumors are positive for the marker CA19-9 in many cases, which may provide a means of follow-up for residual or recurrent disease.

Bavetta S, El-Shunnar K, Hamlyn PJ. Neurenteric cyst of the anterior cranial fossa. Br J Neurosurg. 1996;10:225-227.

Cai C, Shen C, Yang W, et al. Intraspinal neurenteric cysts in children. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35:609-615.

Caldarelli M, Massimi L, Kondageski C, et al. Intracranial midline dermoid and epidermoid cysts in children. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:473-480.

Cavazzani P, Ruelle A, Michelozzi G, et al. Spinal dermoid cysts originating intracranial fat drops causing obstructive hydrocephalus: case reports. Surg Neurol. 1995;43:466-469.

Darrouzet V, Franco-Vidal V, Hilton M, et al. Surgery of cerebellopontine angle epidermoid cysts: role of the widened retrolabyrinthine approach combined with endoscopy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:120-125.

Garg N, Sampath S, Yasha TC, et al. Is total excision of spinal neurenteric cysts possible? Br J Neurosurg. 2008;22:241-251.

Gormley WB, Tomecek FJ, Qureshi N, et al. Craniocerebral epidermoid and dermoid tumours: a review of 32 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1994;128:115-121.

Groen RJ, van Ouwerkerk WJ. Cerebellar dermoid tumor and occipital meningocele in a monozygotic twin: clues to the embryogenesis of craniospinal dysraphism. Childs Nerv Syst. 1995;11:414-417.

Hakyemez B, Aksoy U, Yildiz H, et al. Intracranial epidermoid cysts: diffusion-weighted, FLAIR and conventional MR findings. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54:214-220.

Hamlat A, Hua ZF, Saikali S, et al. Malignant transformation of intra-cranial epithelial cysts: systematic article review. J Neurooncol. 2005;74:187-194.

Harris CP, Dias MS, Brockmeyer DL, et al. Neurenteric cysts of the posterior fossa: recognition, management, and embryogenesis. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:893-897.

Ho LC, Olivi A, Cho CH, et al. Well-differentiated papillary adenocarcinoma arising in a supratentorial enterogenous cyst: case report. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:1474-1477.

Inoue Y, Ohata K, Nakayama K, et al. An unusual middle fossa interdural epidermoid tumor. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:902-904.

Kallmes DF, Provenzale JM, Cloft HJ, et al. Typical and atypical MR imaging features of intracranial epidermoid tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:883-887.

Kim CY, Wang KC, Choe G, et al. Neurenteric cyst: its various presentations. Childs Nerv Syst. 1999;15:333-341.

Li F, Zhu S, Liu Y, et al. Hyperdense intracranial epidermoid cysts: a study of 15 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2007;149:31-39.

Liu JK, Gottfried ON, Salzman KL, et al. Ruptured intracranial dermoid cysts: clinical, radiographic, and surgical features. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:377-384.

Love J, Kernohan J. Dermoid and epidermoid tumors (cholesteatomas) of central nervous system. JAMA. 1936;107:1876-1883.

Mittler MA, McComb JG. Adjacent thoracic neuroenteric and arachnoid cysts. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;30:164-165.

Ogden AT, Khandji AG, McCormick PC, et al. Intramedullary inclusion cysts of the cervicothoracic junction. Report of two cases in adults and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:236-242.

Orakcioglu B, Halatsch ME, Fortunati M, et al. Intracranial dermoid cysts: variations of radiological and clinical features. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150:1227-1234.

Osborn AG, Preece MT. Intracranial cysts: radiologic-pathologic correlation and imaging approach. Radiology. 2006;239:650-664.

Pang D, Dias MS, Ahab-Barmada M. Split cord malformation: Part I: A unified theory of embryogenesis for double spinal cord malformations. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:451-480.

Rivierez M, Buisson G, Kujas M, et al. Intramedullary neurenteric cyst without any associated malformation. One case evaluated by RMI and electron microscopic study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1997;139:887-890.

Sano K. Intracranial dysembryogenetic tumors: pathogenesis and their order of malignancy. Neurosurg Rev. 2001;24:162-167.

1 Orakcioglu B, Halatsch ME, Fortunati M, et al. Intracranial dermoid cysts: variations of radiological and clinical features. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150:1227-1234.

2 Osborn AG, Preece MT. Intracranial cysts: radiologic-pathologic correlation and imaging approach. Radiology. 2006;239:650-664.

3 Dias MS, Walker ML. The embryogenesis of complex dysraphic malformations: a disorder of gastrulation? Pediatr Neurosurg. 1992;18:229-253.

4 Akar Z, Tanriover N, Tuzgen S, et al. Surgical treatment of intracranial epidermoid tumors. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2003;43:275-280.

5 Li F, Zhu S, Liu Y, et al. Hyperdense intracranial epidermoid cysts: a study of 15 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2007;149:31-39.

6 Caldarelli M, Massimi L, Kondageski C, et al. Intracranial midline dermoid and epidermoid cysts in children. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:473-480.

7 Kumari R, Guglani B, Gupta N, et al. Intracranial epidermoid cyst: magnetic resonance imaging features. Neurol India. 2009;57:359-360.

8 Darrouzet V, Franco-Vidal V, Hilton M, et al. Surgery of cerebellopontine angle epidermoid cysts: role of the widened retrolabyrinthine approach combined with endoscopy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:120-125.

9 Roux A, Mercier C, Larbrisseau A, et al. Intramedullary epidermoid cysts of the spinal cord. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:528-533.

10 Ogden AT, Khandji AG, McCormick PC, et al. Intramedullary inclusion cysts of the cervicothoracic junction. Report of two cases in adults and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:236-242.

11 Love J, Kernohan J. Dermoid and epidermoid tumors (cholesteatomas) of central nervous system. JAMA. 1936;107:1876-1883.

12 Gormley WB, Tomecek FJ, Qureshi N, et al. Craniocerebral epidermoid and dermoid tumours: a review of 32 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1994;128:115-121.

13 Sano K. Intracranial dysembryogenetic tumors: pathogenesis and their order of malignancy. Neurosurg Rev. 2001;24:162-167.

14 Iaconetta G, Carvalho GA, Vorkapic P, et al. Intracerebral epidermoid tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2001;55:218-222.

15 Inoue Y, Ohata K, Nakayama K, et al. An unusual middle fossa interdural epidermoid tumor. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:902-904.

16 Hakyemez B, Aksoy U, Yildiz H, et al. Intracranial epidermoid cysts: diffusion-weighted, FLAIR and conventional MR findings. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54:214-220.

17 Kallmes DF, Provenzale JM, Cloft HJ, et al. Typical and atypical MR imaging features of intracranial epidermoid tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:883-887.

18 Agarwal S, Rishi A, Suri V, et al. Primary intracranial squamous cell carcinoma arising in an epidermoid cyst—a case report and review of literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109:888-891.

19 Hamlat A, Hua ZF, Saikali S, et al. Malignant transformation of intra-cranial epithelial cysts: systematic article review. J Neurooncol. 2005;74:187-194.

20 Takeshita M, Kubo O, Tajika Y, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of carbohydrate determinant 19-9 (CA 19-9) in intracranial epidermoid and dermoid cysts. Surg Neurol. 1993;40:284-288.

21 Groen RJ, van Ouwerkerk WJ. Cerebellar dermoid tumor and occipital meningocele in a monozygotic twin: clues to the embryogenesis of craniospinal dysraphism. Childs Nerv Syst. 1995;11:414-417.

22 Turgut M. Klippel-Feil syndrome in association with posterior fossa dermoid tumour. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2009;151:269-276.

23 Brown JY, Morokoff AP, Mitchell PJ, et al. Unusual imaging appearance of an intracranial dermoid cyst. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1970-1972.

24 Liu JK, Gottfried ON, Salzman KL, et al. Ruptured intracranial dermoid cysts: clinical, radiographic, and surgical features. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:377-384.

25 Cavazzani P, Ruelle A, Michelozzi G, et al. Spinal dermoid cysts originating intracranial fat drops causing obstructive hydrocephalus: case reports. Surg Neurol. 1995;43:466-469.

26 Garg N, Sampath S, Yasha TC, et al. Is total excision of spinal neurenteric cysts possible? Br J Neurosurg. 2008;22:241-251.

27 Bavetta S, El-Shunnar K, Hamlyn PJ. Neurenteric cyst of the anterior cranial fossa. Br J Neurosurg. 1996;10:225-227.

28 Wang W, Piao YS, Gui QP, et al. Cerebellopontine angle neurenteric cyst with focal malignant features. Neuropathology. 2009;29:91-95.

29 Cai C, Shen C, Yang W, et al. Intraspinal neurenteric cysts in children. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35:609-615.

30 Rivierez M, Buisson G, Kujas M, et al. Intramedullary neurenteric cyst without any associated malformation. One case evaluated by MRI and electron microscopic study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1997;139:887-890.

31 Harris CP, Dias MS, Brockmeyer DL, et al. Neurenteric cysts of the posterior fossa: recognition, management, and embryogenesis. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:893-897.

32 Pang D, Dias MS, Ahab-Barmada M. Split cord malformation: Part I: A unified theory of embryogenesis for double spinal cord malformations. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:451-480.

33 Kincaid PK, Stanley P, Kovanlikaya A, et al. Coexistent neurenteric cyst and enterogenous cyst. Further support for a common embryologic error. Pediatr Radiol. 1999;29:539-541.

34 Gumerlock MK, Spollen LE, Nelson MJ, et al. Cervical neurenteric fistula causing recurrent meningitis in Klippel-Feil sequence: case report and literature review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10:532-535.

35 Chaynes P, Bousquet P, Sol JC, et al. Recurrent intracranial neurenteric cysts. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140:905-911.

36 Shakudo M, Inoue Y, Ohata K, et al. Neurenteric cyst with alteration of signal intensity on follow-up MR images. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:496-498.

37 Kim CY, Wang KC, Choe G, et al. Neurenteric cyst: its various presentations. Childs Nerv Syst. 1999;15:333-341.

38 Mittler MA, McComb JG. Adjacent thoracic neuroenteric and arachnoid cysts. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;30:164-165.

39 Ho LC, Olivi A, Cho CH, et al. Well-differentiated papillary adenocarcinoma arising in a supratentorial enterogenous cyst: case report. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:1474-1477.