Chapter 88 Endovascular Treatment of Extracranial Occlusive Disease

Stroke is currently the third leading cause of death in the United States.1 Carotid occlusive disease is the underlying pathology for 25% of the estimated 750,000 annual strokes.2–4 The prevalence of carotid stenosis is 0.5% after age 60 and increases to 10% in the population older than 80 years.5–7 There is a direct correlation between the degree of carotid artery stenosis and the risk of ipsilateral stroke.8 The majority of cases of carotid stenosis are asymptomatic; however, symptomatic stroke treatment and lost productivity due to stroke account for an estimated annual cost of $74 billion.9 The clinical and fiscal significance of stroke-related disabling morbidity has led to medical and surgical treatments for carotid occlusive disease, the goals of which lie in lowering the risk of stroke.

In the past, medical treatment for carotid occlusive disease was based on strategies stemming from studies directed at the treatment of general cardiovascular disease. However, more recently, prospective, randomized, controlled studies have proved a combination of surgical carotid revascularization by means of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and medical management is highly successful in reducing the incidence of stroke among patients with moderate to severe symptomatic carotid stenosis10 and among those with severe asymptomatic carotid stenosis.3 CEA has been the standard of care for surgical revascularization for carotid occlusive disease; however, since the 1990s, carotid artery stenting (CAS) has evolved as an alternative treatment to CEA when dealing with patients deemed to be too high a surgical risk. High-risk patients account for up to one third of the patients undergoing CEA.11,12 CAS is an attractive alternative to CEA because it is less invasive, has less risk for cranial nerve damage, and has the ability to treat lesions that are anatomically out of reach or too difficult for CEA.12

Indications and Patient Selection

There is irrefutable evidence that for certain patient populations CEA offers an advantage over best medical treatment (BMT) alone. The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) generated prospective, randomized data demonstrating symptomatic patients with carotid stenosis greater than 70% and a perioperative stroke or death rate below 6% are best treated by CEA over BMT alone.13,14 The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program (VACSP) also found a beneficial effect of CEA when compared to BMT.15 The Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS) proved asymptomatic patients with carotid stenosis of greater than 60% could benefit from CEA with a reduction in 5-year ipsilateral stroke risk, provided that their perioperative stroke or death rate was less than 3% and their modifiable risk factors were aggressively treated.16 Based on the preceding results, the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association has published guidelines and indications for CEA.17 However, these key trials excluded patients deemed to be high risk for CEA. The initial indications for CAS were some of the key exclusion criteria from NASCET, VACSP, and ACAS, including restenosis after CEA, contralateral internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusion, previous neck irradiation, advanced age, renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and severe cardiopulmonary disease. The increasing use of CAS has led investigators to question whether either revascularization procedure is more beneficial over the other. Over the last 10 years, multiple studies have attempted to answer that question; however, variability in study design, technology used, and patient selection have made a comparison between CAS and CEA difficult.12,18–22 It is beyond the scope of this chapter to detail individual study design flaws, results, and criticisms; however, several study trials have helped influence patient selection for CAS in my practice. The trial that led to U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for CAS was the Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy (SAPPHIRE). The SAPPHIRE study led to a general sense that CAS was at least equivalent to CEA in high-risk patients. SAPPHIRE 30-day myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and death rates were 4.8% in the CAS arm versus 9.8% in the CEA arm (P = 0.09).12 One-year MI, ipsilateral stroke, and death rates were 12.2% in CAS versus 20.1% in CEA (P = 0.048). The 3-year incidence of stroke was 7% for both CAS and CEA. The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST) randomized 1326 symptomatic and 1196 asymptomatic patients to CAS or CEA with a median follow-up period of 2.5 years. This study recently concluded that among patients with symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid stenosis, the risk of the composite primary outcome of stroke, MI, or death did not differ significantly in the groups treated by CAS from those treated by CEA.18 This study did find a higher risk of periprocedural stroke with stenting (4.1% vs. 2.3%, P = 0.01) and periprocedural MI with endarterectomy (1.1% vs. 2.3%, P = 0.03). Further, quality-of-life analyses among survivors at 1 year indicated that stroke had a greater adverse effect than did MI on a range of health-status domains. It is the current practice of my colleagues and I to offer CAS to asymptomatic or symptomatic patients who would benefit from CEA but are deemed to be too high a surgical risk for CEA.

Preoperative Preparation

In our practice, all patients considered for CAS are started on aspirin at a dosage of 325 mg daily at least 5 days prior to the procedure. My colleagues and I also start clopidogrel at least 24 hours prior to the procedure but preferably 3 to 5 days prior to intervention. Clopidogrel is loaded as a 300-mg dose the day before or 75 mg daily 5 days prior to intervention. Some evidence suggests the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel decreases restenosis by inhibiting myointimal proliferation.23–25 In emergent cases in which patients are not pretreated, patients are loaded the day of surgery with aspirin at 325 mg and clopidogrel at 300 mg. After the angiogram is completed and the determination to proceed with CAS is made, 4000 U of heparin is administered intravenously and redosed at 1000 U every hour until completion of the stenting procedure. Although not a standard of care, many surgeons check activated coagulation times with the practice of anticoagulating to achieve the goal of doubling these times.

Procedure

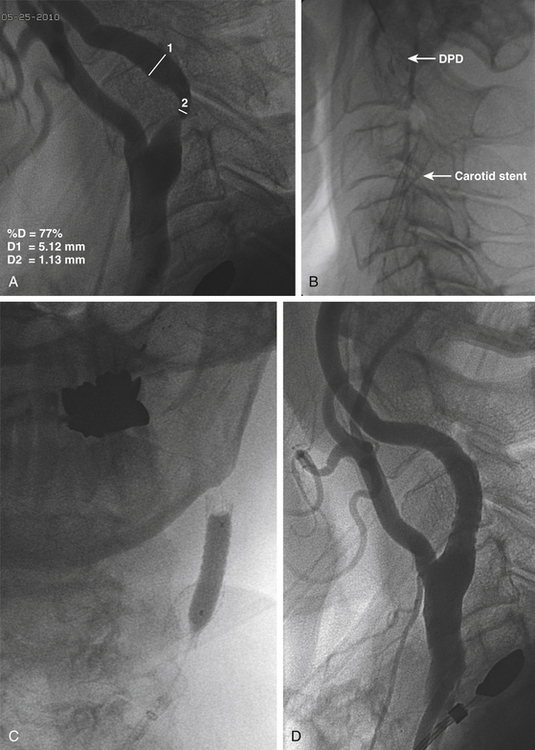

The 0.035-inch exchange-length wire (and 5-Fr diagnostic catheter, if used) is removed, and more accurate measurements using a magnified cervical carotid arteriogram are performed using the 8-Fr outer diameter of the sheath as the measurement standard. The stenosis is determined according to NASCET criteria (Fig. 88-1A). The diameter of a straight portion of the ICA distal to the stenosis is determined to select the appropriate size of the distal protection device (DPD) and the appropriate diameter of the angioplasty balloon. The diameter of the CCA and the length of the stenosis are also determined to ensure selection of the appropriate length and diameter of the carotid stent. The carotid stent is sized so that it is 1 mm greater in diameter than the CCA.

Next, the DPD is mounted on a 0.014-inch wire and advanced past the stenosis into the distal ICA under fluoroscopic guidance. The filter basket is deployed, with the surgeon taking care to position the filter distal enough to the stenosis to allow for positioning of the stent (Fig. 88-1B). My colleagues and I have found a very gentle curve on the guidewire tip helps the surgeon manipulate the wire past the stenosis. At this stage, we prefer to position and deploy the self-expanding carotid stent (Fig. 88-1C and D) in cases where the degree of stenosis will allow this, but we predilate with angioplasty if the degree of stenosis is severe enough to make stent passage difficult. If the lesion cannot be crossed with the DPD, the options are to perform the procedure without distal protection or the use of a proximal protection device that relies on flow reversal.26 Once the stent is deployed and stent position is confirmed, the stent delivery system is removed over the 0.014-inch wire. Angioplasty is then performed under fluoroscopy (Fig. 88-1C). It is important to warn the anesthesia team prior to angioplasty, because this step can induce profound bradycardia, requiring treatment with atropine. This is particularly true when angioplasty involves the carotid bulb.

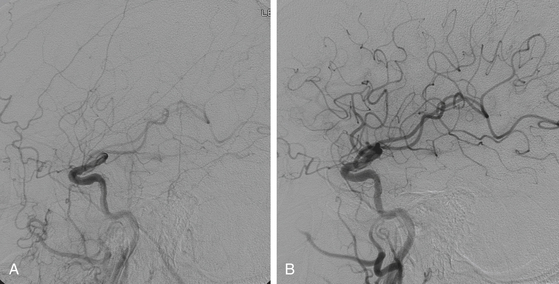

The final step is removal of the DPD with a DPD recapture catheter. Occasionally, if the stent extends around a turn in the carotid, it can be difficult to pass the retrieval catheter. In this case, removal is aided by straightening the stented section of the ICA by gentle external manipulation of the carotid artery or by the use of a second 0.014-inch wire as a “buddy wire.” The basket should be inspected for any debris. Prior to removal of the sheath, a poststent arteriogram is performed (Fig. 88-2). My colleagues and I routinely perform a poststent cerebral arteriogram and compare it to our initial prestent arteriogram to assess for any thromboembolic events during the stenting or angioplasty.

Postoperative Care

Following CAS, almost all postoperative patients are sent to monitored floor beds for overnight observation and discharged home the following day. If there was significant intraprocedural hemodynamic change or there continues to be profound hemodynamic aberrations postoperatively, my colleagues and I monitor the patient in an intensive care unit until hemodynamic instability has resolved.

Complications

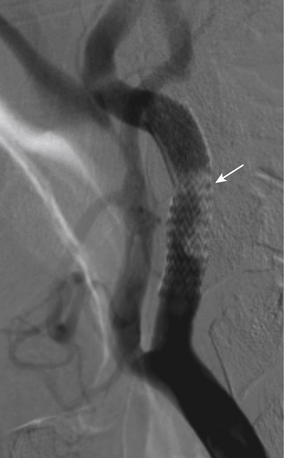

Following successful deployment of the carotid stent and removal of the DPD, a repeat cerebral arteriogram is performed and compared with the prestent cerebral arteriogram to assess for any large vessel occlusions. If a large vessel occlusion is identified, treatment options include intra-arterial tissue plasminogen activator or intra-arterial abciximab. Another option is mechanical thromboembolectomy using the Penumbra System (Penumbra, Alameda, CA).27 In rare cases where thrombosis is seen in the stent, my colleagues and I have used intravenous abciximab, because the thrombus is felt to be an acute platelet aggregation (Fig. 88-3).

Outcome Data

The endovascular technique for CAS presented here has produced acceptable results in asymptomatic and symptomatic high-risk patients with carotid stenosis.28 In a review of treatment outcomes found by my colleagues and I for 101 consecutive patients (109 stents), in which DPDs were used in 72% of the cases treated, the overall in-hospital adverse event rate was 8.3%. Periprocedural events included, 2 patients (1.8%) experienced a hemispheric transient ischemic attack, 2 patients (1.8%) had transiently symptomatic acute reperfusion syndrome, and 1 patient (0.9%) died of an MI. The 30-day MI, stroke, and death outcome included 3 patients (2.7%) with minor strokes, defined as a modified Rankin score of less than 3, at 1-year follow-up and 1 patient (0.9%) with a major stroke, defined as a modified Rankin score of 3 or more, at 1-year follow-up.

Conclusions

We presented the technique and outcomes at our clinic for CAS treatment of high-risk patients with extracranial carotid disease. Despite the debate generated by several large trials attempting to compare CAS and CEA,12,18–22 my colleagues and I feel that—with proper patient selection, evolving endovascular technology, and attention to interventional technique—CAS is a viable option for high-risk surgical patients. Improved periprocedural outcomes in both our data and the most recent CREST add credence to CAS for extracranial carotid disease in the high-surgical-risk population.

Bledsoe S.L., et al. Effect of clopidogrel on platelet aggregation and intimal hyperplasia following carotid endarterectomy in the rat. Vascular. 2005;13(1):43-49.

Biller J., et al. Guidelines for carotid endarterectomy: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 1998;29(2):554-562.

Brott T.G., Hobson R.W.2nd, Howard G., et al. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 1;363(1):1-23. Epub 2010 May 26

Coppi G., et al. PRIAMUS—proximal flow blockage cerebral protection during carotid stenting: results from a multicenter Italian registry. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2005;46(3):219-227.

Eckstein H.H., et al. Results of the Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy (SPACE) study to treat symptomatic stenoses at 2 years: a multinational, prospective, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(10):893-902.

Ederle J., et al. Endovascular treatment with angioplasty or stenting versus endarterectomy in patients with carotid artery stenosis in the Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS): long-term follow-up of a randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(10):898-907.

Goncu T., et al. Inhibitory effects of ticlopidine and clopidogrel on the intimal hyperplastic response after arterial injury. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2010;10(1):11-16.

Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics. 2010 Update At-A-Glance. American Heart Association; 2010.

Herbert J.M., et al. The antiaggregating and antithrombotic activity of clopidogrel is potentiated by aspirin in several experimental models in the rabbit. Thromb Haemost. 1998;80(3):512-518.

Mas J.L., et al. Endarterectomy versus stenting in patients with symptomatic severe carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(16):1660-1671.

Mayberg M.R., et al. Carotid endarterectomy and prevention of cerebral ischemia in symptomatic carotid stenosis. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program 309 Trialist Group. JAMA. 1991;266(23):3289-3294.

Meyer S.A., Gandhi C.D., Johnson D.M., Winn H.R., Patel A.B., et al. Outcomes of carotid artery stenting in high-risk patients with carotid artery stenosis: A single neurovascular center retrospective review of 101 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(3):448-453. discussion 453-454

Moore W.S., et al. Carotid endarterectomy: practice guidelines. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee to the Joint Council of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the North American Chapter of the International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 1992;15(3):469-479.

North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial. Methods, patient characteristics, and progress. Stroke. 1991;22(6):711-720.

North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(7):445-453.

O’Leary D.H., et al. Distribution and correlates of sonographically detected carotid artery disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. The CHS Collaborative Research Group. Stroke. 1992;23(12):1752-1760.

Prati P., et al. Prevalence and determinants of carotid atherosclerosis in a general population. Stroke. 1992;23(12):1705-1711.

Ricci S., et al. (The prevalence of stenosis of the internal carotid in subjects over 49: a population study.). Epidemiol Prev. 1991;13(48-49):173-176.

Ringleb P.A., et al. 30 day results from the SPACE trial of stent-protected angioplasty versus carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1239-1247.

Rosamond W., et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115(5):e69-e171.

Rothwell P.M., et al. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet. 2003;361(9352):107-116.

Wennberg D.E., et al. Variation in carotid endarterectomy mortality in the Medicare population: trial hospitals, volume, and patient characteristics. JAMA. 1998;279(16):1278-1281.

Yadav J.S., et al. Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1493-1501.

Young B., et al. An analysis of perioperative surgical mortality and morbidity in the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. Stroke. 1996;27(12):2216-2224.

1. Rosamond W., et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115(5):e69-e171.

2. DeBakey M.E. Carotid endarterectomy revisited. J Endovasc Surg. 1996;3(1):4.

3. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA. 1995;273(18):1421-1428.

4. Moore W.S., et al. Carotid endarterectomy: practice guidelines. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee to the Joint Council of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the North American Chapter of the International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 1992;15(3):469-479.

5. Ricci S., et al. The prevalence of stenosis of the internal carotid in subjects over 49: a population study. Epidemiol Prev. 1991;13(48-49):173-176.

6. Prati P., et al. Prevalence and determinants of carotid atherosclerosis in a general population. Stroke. 1992;23(12):1705-1711.

7. O’Leary D.H., et al. Distribution and correlates of sonographically detected carotid artery disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. The CHS Collaborative Research Group. Stroke. 1992;23(12):1752-1760.

8. Culebras A., Magana R., Cacayorin E.D. Computed tomography of the cervical carotid artery: significance of the lucent defect. Stroke. 1988;19(6):723-727.

9. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics. 2010 Update At-A-Glance. American Heart Association; 2010.

10. Rothwell P.M., et al. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet. 2003;361(9352):107-116.

11. Wennberg D.E., et al. Variation in carotid endarterectomy mortality in the Medicare population: trial hospitals, volume, and patient characteristics. JAMA. 1998;279(16):1278-1281.

12. Yadav J.S., et al. Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1493-1501.

13. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial. Methods, patient characteristics, and progress. Stroke. 1991;22(6):711-720.

14. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(7):445-453.

15. Mayberg M.R., et al. Carotid endarterectomy and prevention of cerebral ischemia in symptomatic carotid stenosis. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program 309 Trialist Group. JAMA. 1991;266(23):3289-3294.

16. Young B., et al. An analysis of perioperative surgical mortality and morbidity in the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. Stroke. 1996;27(12):2216-2224.

17. Biller J., et al. Guidelines for carotid endarterectomy: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 1998;29(2):554-562.

18. Brott T.G., Hobson R.W.2nd, Howard G., et al. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):11-23.

19. Ringleb P.A., et al. 30 day results from the SPACE trial of stent-protected angioplasty versus carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1239-1247.

20. Eckstein H.H., et al. Results of the Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy (SPACE) study to treat symptomatic stenoses at 2 years: a multinational, prospective, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(10):893-902.

21. Mas J.L., et al. Endarterectomy versus stenting in patients with symptomatic severe carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(16):1660-1671.

22. Ederle J., et al. Endovascular treatment with angioplasty or stenting versus endarterectomy in patients with carotid artery stenosis in the Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS): long-term follow-up of a randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(10):898-907.

23. Goncu T., et al. Inhibitory effects of ticlopidine and clopidogrel on the intimal hyperplastic response after arterial injury. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2010;10(1):11-16.

24. Bledsoe S.L., et al. Effect of clopidogrel on platelet aggregation and intimal hyperplasia following carotid endarterectomy in the rat. Vascular. 2005;13(1):43-49.

25. Herbert J.M., et al. The antiaggregating and antithrombotic activity of clopidogrel is potentiated by aspirin in several experimental models in the rabbit. Thromb Haemost. 1998;80(3):512-518.

26. Coppi G., et al. PRIAMUS—proximal flow blockage cerebral protection during carotid stenting: results from a multicenter Italian registry. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2005;46(3):219-227.

27. The penumbra pivotal stroke trial: safety and effectiveness of a new generation of mechanical devices for clot removal in intracranial large vessel occlusive disease. Stroke. 2009;40(8):2761-2768.

28. Meyer S.A., Gandhi C.D., Johnson D.M., Winn H.R., Patel A.B. Outcomes of carotid artery stenting in high-risk patients with carotid artery stenosis: a single neurovascular center retrospective review of 101 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(3):448-453. discussion 453-454