CHAPTER 61 Endoscopic Treatment of Pancreatic Disease

EARLY ACUTE PANCREATITIS

When a patient presents with acute pancreatitis the role of endoscopy is limited to two situations: first, those patients with gallstone-induced pancreatitis (see Chapters 58 and 66) and second, to provide nutritional support via enteric feeding (see Chapter 5). Gallstone pancreatitis is caused by impaction of a stone within the common channel of the ampulla of Vater, usually transiently. ERCP and biliary sphincterotomy are used to improve the outcome of gallstone pancreatitis by removal of an impacted stone with relief of pancreatic ductal obstruction. Initial studies of patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis and choledocholithiasis used urgent (within 72 hours of admission) ERCP and sphincterotomy (if a stone was identified). An improved outcome was seen only in patients with clinically severe acute pancreatitis.1 Studies now suggest that the improved outcome following ERCP and sphincterotomy in gallstone pancreatitis results from reduced biliary sepsis rather than improvement in pancreatitis.2,3 A meta-analysis showed that early ERCP in patients with predicted mild or severe acute biliary pancreatitis without concomitant acute cholangitis did not significantly reduce overall complications and mortality.4 Similarly, results from a prospective randomized trial showed that ERCP and sphincterotomy could decrease morbidity in patients with gallstones pancreatitis and ampullary obstruction when the duration of obstruction did not exceed 28 hours.5 ERCP in patients with severe gallstone acute pancreatitis is best reserved for patients with suspected biliary obstruction, based on hyperbilirubinemia and evidence of clinical cholangitis because it is unlikely that the ampulla is obstructed in the presence of a normal serum bilirubin.6,7 Other imaging modalities in patients with severe biliary pancreatitis such as EUS and MRCP can help select patients for ERCP when bile duct stones are identified.8,9 If bile duct stones are not identified during ERCP performed for acute gallstone pancreatitis, there are no data to guide whether an empirical biliary sphincterotomy should be performed. However, sphincterotomy can reduce the risk of recurrent acute pancreatitis and cholangitis prior to cholecystectomy.10

Evidence supports enteral feeding for patients with severe acute pancreatitis based on randomized prospective studies comparing total parenteral nutrition with enteral feeding (through a nasoenteric feeding tube placed beyond the ligament of Treitz) instituted within 48 hours of illness onset.11 Lower cost and fewer infectious complications are seen with enteral feeding (see Chapter 5). There are a variety of endoscopic techniques for placing nasojejunal feeding tubes in the setting of acute pancreatitis12 including transnasal endoscopy.13

LOCAL COMPLICATIONS OF ACUTE PANCREATITIS

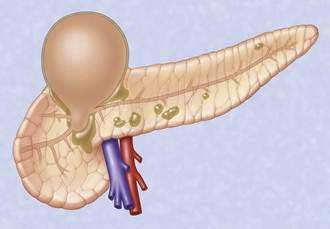

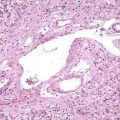

Acute fluid collections, acute pancreatic pseudocysts, organized pancreatic necrosis, and pancreatic abscesses may arise as a result of acute pancreatitis.14 Acute fluid collections form early in the course of acute pancreatitis and usually resolve without therapy. Acute pseudocysts arise as a sequela of acute pancreatitis, require at least four weeks to form, and are devoid of significant solid debris. Acute pancreatic pseudocysts usually form as a result of limited pancreatic necrosis that produces a pancreatic ductal leak (Fig. 61-1). Alternatively, areas of pancreatic and peripancreatic fat necrosis may liquefy over time and become a pseudocyst.15 Despite the requirement of at least four weeks for a pseudocyst to form, it is important to realize that some patients with significant early acute pancreatic necrosis (>30%) may evolve the pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis into a collection that radiographically resembles a pseudocyst.16 These collections contain significant solid debris, and endoscopic treatment of them using typical pseudocyst drainage methods often results in infectious complications because of contamination and inadequate removal of solid debris.17,18

ACUTE PANCREATIC PSEUDOCYST

Drainage of an acute pseudocyst is indicated for treatment of symptomatic pseudocysts that may or may not be infected19 and for progressive enlargement on imaging studies. Symptoms and signs from an acute pseudocyst include abdominal pain, often exacerbated by eating, weight loss, gastric outlet obstruction, obstructive jaundice, and pancreatic duct leakage, which may result in pancreatic ascites or pancreatic fistulae.20 Pseudocysts may be drained through the papilla (transpapillary), through the gastric or duodenal wall (transmurally), or by using a combination of the two.

Transpapillary Drainage

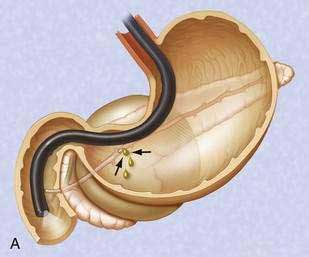

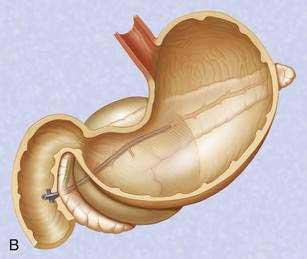

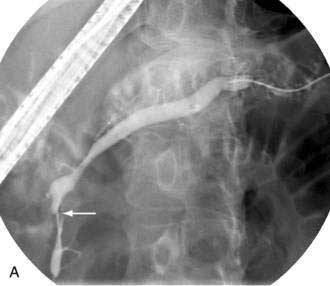

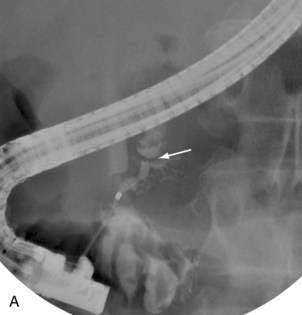

If the pseudocyst communicates with the main pancreatic duct, placement of a pancreatic duct stent with or without pancreatic sphincterotomy is effective, especially for smaller pseudocysts (<5 to 6 cm) that are not otherwise approachable transmurally.21 The proximal end of the stent (toward the pancreatic tail) may directly enter the pseudocyst, bridge the area of leak into the pancreatic duct upstream from the leak, or lie completely downstream to the leak. Bridging the leak is the preferred approach because it restores ductal continuity and appears to be more effective (Fig. 61-2).22,23 Transpapillary drainage avoids bleeding or perforation that may occur with transmural drainage. However, pancreatic stents may induce scarring of the main pancreatic duct.24

Transmural Drainage

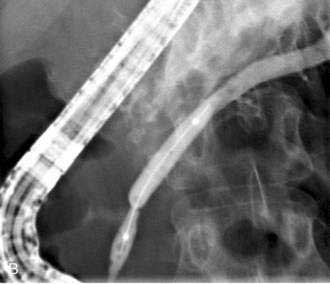

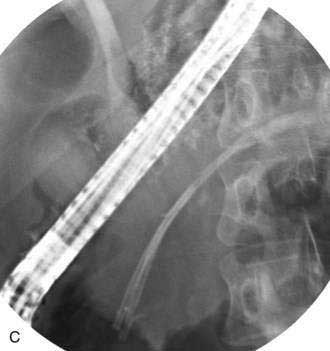

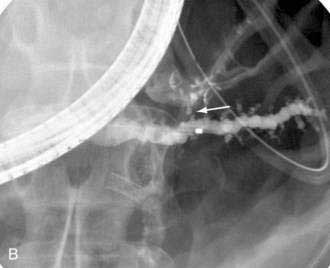

There is no standardized approach to transmural pseudocyst drainage. Transmural drainage is performed by entering the cyst using a needle without cautery or using a cautery device (e.g., needle knife). Some endoscopists believe EUS-guided drainage is mandatory prior to performing endoscopic transmural drainage to prevent bleeding and perforation.25 Although the superiority of EUS-guided versus non–EUS-guided drainage has not been demonstrated,26 there are increasing data to support its routine use during transmural drainage,26–28 especially when non–EUS-guided drainage fails.29 EUS-guided entry is successful in more than 95% of patients and with low complication rates.30–32 Non–EUS-guided entry also can be performed33 and, in the hands of experienced operators, successful transmural entry has been reported in 91 of 94 patients in lesions as small as 3 cm and without endoscopically visible extrinsic compression.34 Once the pseudocyst is successfully entered, the transmural tract is balloon dilated to 8 to 10 mm in diameter to allow placement of one or two 10-French stents (Fig. 61-3).35

Following uncomplicated attempted endoscopic drainage, a follow-up CT is obtained four to six weeks after the procedure. The internal stents are endoscopically removed after documented radiographic pseudocyst resolution. Success rates, recurrence rates, and complication rates of endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts are variable, likely because of many reports included acute and chronic pseudocysts and pancreatic abscesses. In addition, some patients underwent transpapillary drainage and others underwent transmural drainage. Nonetheless, cumulatively successful drainage is achieved in approximately 75% to 90%, with complication rates of about 5% to 10% and pseudocyst recurrence rates of 5% to 20%.36,37

ORGANIZED PANCREATIC NECROSIS (WALLED-OFF PANCREATIC NECROSIS)

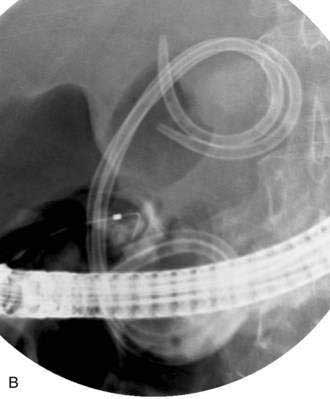

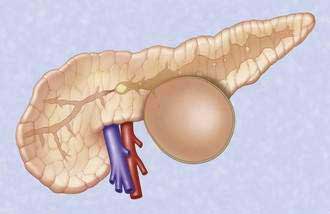

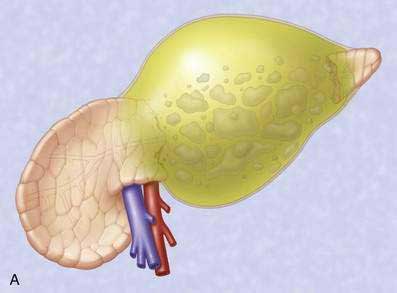

Pancreatic necrosis is nonviable pancreatic parenchyma, usually associated with peripancreatic fat necrosis. In the earliest form, this is detected on contrast-enhanced CT by demonstrating areas of nonenhancing pancreatic parenchyma. Pancreatic necrosis is frequently accompanied by major pancreatic ductal disruptions. Over the course of several weeks, the collection may continue to evolve and expand the initial area of necrosis and contains both liquid and solid debris (Fig. 61-4). The terms organized pancreatic necrosis20 and walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN)38 have been used to differentiate this process from the early (acute phase) of pancreatic necrosis. The CT appearance of organized pancreatic necrosis may be mistaken as an acute pseudocyst.16

Figure 61-4. A, Illustration of walled-off (organized) pancreatic necrosis. B, Computed tomography scan of patient with organized pancreatic necrosis. Successful endoscopic therapy using direct necrosectomy was performed (see Fig. 61-5).

The indications for and timing of drainage of sterile WOPN are controversial. Endoscopic drainage cannot be performed until the process becomes organized, which usually occurs several weeks after onset of pancreatitis. Indications for drainage of sterile WOPN are refractory abdominal pain, gastric outlet obstruction or failure to thrive (continued systemic illness, anorexia, and weight loss) at four or more weeks after the onset of acute pancreatitis.38 Because endoscopic drainage of WOPN is more technically difficult, carries a higher rate of complications, and tends to involve more severely ill patients than patients with acute pseudocyst, the decision to endoscopically intervene when the process is sterile pancreatic necrosis must be carefully considered.39 Alternative management options to endoscopic drainage include nutritional support with parenteral or enteral jejunal feeding and nonendoscopic drainage methods such as percutaneous and surgical drainage. The management option selected is usually based on local expertise and severity of comorbid medical illnesses. Ideally, these patients are best managed by a multidisciplinary approach.

Infected necrosis is an indication for drainage. Percutaneous fine-needle aspiration may be required to determine the bacteriologic status prior to intervention.40

Because of the need to evacuate solid material, the endoscopic approach to drainage of WOPN differs from drainage of pseudocysts. In general, the transpapillary approach alone is not adequate because it does not allow removal of solid debris. Therefore, the transmural drainage approach is used. The endoscopic approach has evolved. Initially nasal irrigation tubes were placed of alongside transmurally placed stents in order to lavage the solid debris.41 Subsequent approaches used percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes to provide a method of placing irrigation tubes into the necrotic cavity and avoid uncomfortable transnasal tubes.42,43

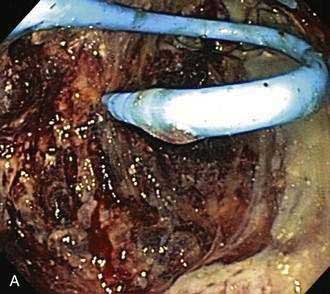

The most recent approach for removal of necrotic debris is to perform direct endoscopic debridement. This is performed by dilating the transmural tract with large-caliber balloons (up to 20 mm) and passing a forward-viewing endoscope through the tract directly into the necrotic cavity (Fig. 61-5).44,45 Snares, grasping forceps, and other accessories are then be used to remove solid debris. This approach has been shown in a retrospective study to be superior to the irrigation approach.46 Nevertheless, repeat procedures are often needed to re-dilate the transmural tract, to debride residual necrotic material, and to attempt to treat underlying pancreatic ductal disruptions in hopes of preventing a ductal disconnection.

Figure 61-5. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy performed in the patient depicted in Figure 61-4. A, Endoscopic view from inside the necrotic cavity; an indwelling pigtail stent is seen with surrounding necrotic debris. B, Necrotic solid material being withdrawn from the cavity through the posterior gastric wall with a snare.

Drainage of pancreatic necrosis is associated with a higher complication rate and longer hospital stay.27,47 Patients with acute pseudocysts tend to have less severe ductal abnormalities and fewer recurrences.

PANCREATIC ABSCESS

When a broad definition of pancreatic abscess is taken to include infected pseudocysts or infected liquefied collections without significant solid debris (pancreatic necrosis), success rates following endoscopic drainage are high, although there are few series with small numbers of patient.47–49

COMPLICATIONS OF ENDOSCOPIC THERAPY OF PANCREATIC FLUID COLLECTIONS

Operator experience likely plays a role in the outcome following endoscopic drainage.50 Life-threatening bleeding or perforation may arise following attempted endoscopic drainage of pancreatic fluid collections. Infectious complications usually occur from inadequate drainage of fluid and solid debris. Infection can usually be managed by additional endoscopic procedures and placement of percutaneous drains. Endoscopic therapy followed by complications may adversely alter the surgical outcome as compared to patients undergoing primary surgical therapy.51,52

RECURRENT ACUTE PANCREATITIS

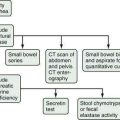

Recurrent acute pancreatitis presents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. In about 10% to 22% of such cases, it is not possible to establish the etiology of the disease.53 Multiple factors discussed in other chapters may be involved with episodes of recurrent acute pancreatitis including alcohol use, microlithiasis, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD), pancreas divisum, hereditary pancreatitis, gene mutations, cystic fibrosis, choledochocele, annular pancreas, anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction, ampullary lesions, pancreatic tumors, and autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP).49

EUS is considered an important tool for evaluating for possible causes of recurrent acute pancreatitis.54 EUS with high resolution allows detection of gallstones, sludge, and microlithiasis55 that can direct treatment toward cholecystectomy or ERCP. In addition, a diagnosis of AIP can be suspected based on ultrasonographic findings and confirmed by EUS-FNA or Tru-cut biopsies.56 In patients with otherwise unexplained recurrent acute pancreatitis after exhaustive clinical and laboratory evaluation and EUS, measurement of pancreatic sphincter pressure by ERCP with pancreaticobiliary manometry can allow the diagnosis of pancreatic sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.57 Subsequent biliary and pancreatic sphincterotomy (when elevated sphincter pressures are identified) may prevent recurrent attacks of pancreatitis.

Pancreas divisum is present in approximately 10% of the population (see Chapter 55) and results from failure of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts to fuse.58 The role of pancreas divisum as a cause of pancreatitis is controversial, but it is believed that in a subset of patients the minor papilla produces functional obstruction to the flow of pancreatic secretions. Pancreas divisum can be diagnosed by CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or EUS. Secretin MRCP may predict which patients have functional minor papilla obstruction.59 Pancreas divisum is confirmed by cannulation of the minor papilla, which can be facilitated by intravenous administration of secretin. Endoscopic minor papilla sphincterotomy in properly selected patients without extensive changes of chronic pancreatitis can reduce or prevent further attacks of acute pancreatitis.60–62

CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

A variety of endoscopic interventions can be performed in patients with chronic pancreatitis (Table 61-1).63

Table 61-1 Endoscopic Therapies for Chronic Pancreatitis

PANCREATIC DUCTAL ENDOTHERAPY

Pancreatic duct strictures and pancreatic duct stones frequently coexist, cause obstruction to the main pancreatic duct, and may contribute to abdominal pain and episodes of acute pancreatitis superimposed on chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopic therapy of pancreatic duct strictures is performed with balloon or catheter dilation followed by placement of one or more plastic pancreatic stents (Fig. 61-6).64 Stents are exchanged and remain in place for a variable period of time.

Pancreatic sphincterotomy and stone removal can rarely be successfully performed using standard biliary stone removal techniques because the stones are calcified and usually impacted within side branches and pancreatic duct strictures. Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL), if available, can be used to fragment stones prior to or without endoscopic removal.65–67 Intraductal lithotripsy under pancreatoscopic guidance has also been used to fragment and remove obstructing stones.68 Pancreatic endotherapy has a high rate of initial technical success.69 In some series long-term clinical success has been achieved in two thirds of patients without need for surgery and with a significant reduction in annual rate of hospitalizations for pain.65,70

Two prospective randomized studies comparing endotherapy and surgery for patients with painful obstructive chronic pancreatitis have been performed.71,72 Endotherapy was associated with a higher number of procedures, and pain improvement was seen more often in the surgical groups. There were limitations to endotherapy in both of these studies, however, namely, lack of availability of ESWL in one study and less aggressive endoscopic stricture therapy in another.73

In cases in which transpapillary approaches are not possible for treatment of pancreatic duct obstruction because of impassable stones or strictures within the pancreatic head, EUS-guided transgastric pancreatic duct puncture can be performed. This can facilitate a rendezvous procedure74 or provide transgastric or transduodenal ductal stent placement.75

DRAINAGE OF CHRONIC PANCREATIC PSEUDOCYSTS

The mechanism of formation of a chronic pseudocyst is different than an acute pseudocyst. As discussed in Chapter 59, chronic pseudocysts arise as a sequela of chronic pancreatitis and downstream pancreatic ductal obstruction from fibrotic strictures or stones (Fig. 61-7).76 This results in a pancreatic ductal blowout (leak) and accumulation of pancreatic fluid. These collections do not contain solid debris and usually do not arise as a result of acute inflammatory processes. The endoscopic approach to chronic pancreatic pseudocysts is as described for acute pseudocysts earlier. The main difference is that the underlying ductal abnormalities may lead to recurrences if left untreated.77,78

BILIARY STRICTURES

The fibrosing process within the pancreatic head can encase the distal bile duct and result in formation of a biliary stricture. Possible sequelae include hepatic fibrosis (secondary biliary cirrhosis) and cholangitis. Balloon dilation and endoscopic insertion of multiple plastic stents across the biliary stricture may result in nonsurgical resolution.79–81 Patients with noncalcific pancreatitis appear to respond better to biliary stricture dilation than those with calcific pancreatitis. Endoscopic insertion of biliary stents can be used for treatment of benign biliary obstruction due to chronic pancreatitis in several situations: (1) preoperative placement for relief of jaundice or cholangitis, (2) temporary placement when biliary obstruction occurs following recent acute pancreatitis superimposed on chronic pancreatitis, (3) long-term therapy of refractory strictures.79 Placement of covered self-expandable metal stents with removal at 3 months has resulted in resolution of biliary strictures that were due to chronic pancreatitis in nearly 80% of patients at a minimal follow-up of 12 months.82

PANCREATIC DUCT LEAKS

Pancreatic duct leaks and pancreatic duct disruptions may occur as a sequela of acute or chronic pancreatitis (see Chapters 58 and 59) as well as after pancreatic surgery (Fig. 61-8) and trauma. Leaks can arise from the tail, body, or head of the pancreas. Fluid can then track laterally (toward the spleen or into the abdomen), medially toward the duodenum or bile duct, centrally into the lesser sac, or into the mediastinum or abdomen with resultant pleural effusions and ascites, respectively.

Most pancreatic leaks that occur after pancreatic surgery are already controlled by indwelling surgical drains. Many of these leaks will close over time; endoscopic therapy is reserved for persistent or refractory leaks.85–87 In the absence of a surgical drain, endoscopic therapy is performed to treat symptomatic leaks. Internal leaks that are associated with clinical deterioration or symptoms require intervention.88

Endoscopic intervention for pancreatic duct leaks is similar to that described for pancreatic pseudocysts and necrosis. In the setting of a large pancreatic fluid collection, transmural drainage of the collection may be undertaken, with or without concomitant transpapillary therapy. This will control the leak internally. In the absence of a pancreatic fluid collection, the treatment is transpapillary pancreatic duct stent placement to promote internal drainage.20,89

Transpapillary therapy is performed with the intent of crossing the site of the leak,22 though it is not feasible when leaks follow pancreatic tail resection or are located at the pancreatic tail, because the stent would be located outside the pancreatic duct. In this situation, the tip of the stent is positioned downstream to the site of leakage.

In patients with external drains in whom endoscopic therapy is being performed to allow drainage removal, success depends on the size of the external drain as compared with the size of the internal stent. Downsizing, clamping, or removing the external drain after successful endoscopic stent placement can promote internal drainage and fistula closure. A variety of glues have been used to seal pancreatic fistula and leaks,90,91 though these glues are not U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved and they have the potential for occlusion of the main pancreatic duct.

PANCREATIC CANCER

Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic cancer primarily involves palliation of malignant biliary obstruction via ERCP placement of transpapillary biliary stents (see Chapters 60 and 70). In some patients placement of a stent into the pancreatic duct can relieve abdominal pain from pancreatic ductal obstruction.92 In addition, some pancreatic cancer patients with pancreatic ductal obstruction will develop pseudocysts or leaks; endoscopic pancreatic duct stent placement across the pancreatic duct stricture can be useful. Pancreatic head cancer can produce gastric outlet obstruction due to duodenal invasion by tumor in 15% to 20% of patients.93,94 Endoscopic placement of self-expandable metal duodenal stents is an effective palliative method with results comparable to surgical bypass.95 Combined palliation of malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction is also feasible.96 Pancreatic cancer pain can be treated by EUS-guided celiac plexus block using ethanol to allow permanent ablation of the ganglion. This treatment appears to be effective and sustainable.79

PANCREATIC CYSTS

There are a wide variety of pancreatic cysts and cystic neoplasms, as discussed in Chapter 60. CT, MRI, and EUS allow differentiation and direction of management toward observation or surgery.97 Preliminary studies suggest that EUS alcohol injection into specific types of cysts may be a useful nonsurgical alternative.98,99

Baron TH. Treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts, pancreatic necrosis, and pancreatic duct leaks. Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am. 2007;17:559-79. (Ref 20.)

Barthet M, Lamblin G, Gasmi M, et al. Clinical usefulness of a treatment algorithm for pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:245-52. (Ref 21.)

Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: A report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330-6. (Ref 97.)

Cahen DL, Gouma DJ, Nio Y, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:676-84. (Ref 72.)

Cahen D, Rauws E, Fockens P, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: Long-term outcome and procedural factors associated with safe and successful treatment. Endoscopy. 2005;37:977-83. (Ref 35.)

Costamagna G, Bulajic M, Tringali A, et al. Multiple stenting of refractory pancreatic duct strictures in severe chronic pancreatitis: Long-term results. Endoscopy. 2006;38:254-9. (Ref 81.)

Delhaye M, Arvanitakis M, Verset G, et al. Long-term clinical outcome after endoscopic pancreatic ductal drainage for patients with painful chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1096-106. (Ref 69.)

Dumonceau JM, Costamagna G, Tringali A, et al. Treatment for painful calcified chronic pancreatitis: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus endoscopic treatment: A randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2007;56:545-52. (Ref 66.)

Hookey LC, Debroux S, Delhaye M, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections in 116 patients: A comparison of etiologies, drainage techniques, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:635-43. (Ref 27.)

Kwan V, Loh SM, Walsh PR, et al. Minor papilla sphincterotomy for pancreatitis due to pancreas divisum. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:257-61. (Ref 62.)

Petrov MS, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, et al. Early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography versus conservative management in acute biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Surg. 2008;247:250-7. (Ref 4.)

Seewald S, Groth S, Omar S, et al. Aggressive endoscopic therapy for pancreatic necrosis and pancreatic abscess: A new safe and effective treatment algorithm (videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:92-100. (Ref 44.)

Varadarajulu S, Noone TC, Tutuian R, et al. Predictors of outcome in pancreatic duct disruption managed by endoscopic transpapillary stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:568-75. (Ref 23.)

1. Neoptolemos JP, Carr-Locke DL, London NJ, et al. Controlled trial of urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic sphincterotomy versus conservative treatment for acute pancreatitis due to gallstones. Lancet. 1988;2:979-83.

2. Fan ST, Lai EC, Mok FP, et al. Early treatment of acute biliary pancreatitis by endoscopic papillotomy. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:228-32.

3. Folsch UR, Nitsche R, Ludtke R, et al. Early ERCP and papillotomy compared with conservative treatment for acute biliary pancreatitis. The German Study Group on Acute Biliary Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:237-42.

4. Petrov MS, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, et al. Early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography versus conservative management in acute biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Surg. 2008;247:250-7.

5. Acosta JM, Katkhouda N, Debian KA, et al. Early ductal decompression versus conservative management for gallstone pancreatitis with ampullary obstruction: A prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2006;243:33-40.

6. Baillie J. Treatment of acute biliary pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:286-7.

7. Working Party of the British Society of GastroenterologyAssociation of Surgeons of Great Britain and IrelandPancreatic Society of Great Britain and IrelandAssociation of Upper GI Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54:iii1-9.

8. Mofidi R, Lee AC, Madhavan KK, et al. The selective use of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in the imaging of the axial biliary tree in patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2008;8:55-60. Epub 2008 Feb 4

9. Romagnuolo J, Currie G, Calgary Advanced Therapeutic Endoscopy Center study group. Noninvasive vs. selective invasive biliary imaging for acute biliary pancreatitis: An economic evaluation by using decision tree analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:86-97.

10. Heider TR, Brown A, Grimm IS, Behrns KE. Endoscopic sphincterotomy permits interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with moderately severe gallstone pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1-5.

11. Petrov MS, Pylypchuk RD, Emelyanov NV. Systematic review: Nutritional support in acute pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Jul 1. [Epub ahead of print]

12. DiSario JA, Baskin WN, Brown RD, et al. Endoscopic approaches to enteral nutritional support. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:901-8.

13. Kulling D, Bauerfeind P, Fried M. Transnasal versus transoral endoscopy for the placement of nasoenteral feeding tubes in critically ill patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:506-10.

14. Baron TH, Morgan DE. The diagnosis and management of fluid collections associated with pancreatitis. Am J Med. 1997;102:555-63.

15. Kloppel G. Pathology of severe acute pancreatitis. In: Bradley ELIII, editor. Acute pancreatitis: Diagnosis and therapy. New York: Raven Press; 1994:35-46.

16. Takahashi N, Papachristou GI, Schmit GD, et al. CT findings of walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN): Differentiation from pseudocyst and prediction of outcome after endoscopic therapy. Eur Radiol. 2008 Jun 18. [Epub ahead of print]

17. Hariri M, Slivka A, Carr-Locke DL, et al. Pseudocyst drainage predisposes to infection when pancreatic necrosis is unrecognized. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1781-4.

18. Soliani P, Franzini C, Ziegler S, et al. Pancreatic pseudocysts following acute pancreatitis: risk factors influencing therapeutic outcomes. JOP. 2004;5:338-47.

19. Baron TH. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:369-72.

20. Baron TH. Treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts, pancreatic necrosis, and pancreatic duct leaks. Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am. 2007;17:559-79.

21. Barthet M, Lamblin G, Gasmi M, et al. Clinical usefulness of a treatment algorithm for pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:245-52.

22. Telford JJ, Farrell JJ, Saltzman JR, et al. Pancreatic stent placement for duct disruption. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:18-24.

23. Varadarajulu S, Noone TC, Tutuian R, et al. Predictors of outcome in pancreatic duct disruption managed by endoscopic transpapillary stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:568-75.

24. Rashdan A, Fogel EL, McHenry LJr, et al. Improved stent characteristics for prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:322-9.

25. Yusuf TE, Baron TH. Endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: results of a national and an international survey of ASGE members. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:223-7.

26. Kahaleh M, Shami VM, Conaway MR, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst: A prospective comparison with conventional endoscopic drainage. Endoscopy. 2006;38:355-9.

27. Hookey LC, Debroux S, Delhaye M, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections in 116 patients: A comparison of etiologies, drainage techniques, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:635-43.

28. Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Tamhane A, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing EUS and EGD for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1102-11.

29. Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM, Tamhane A, et al. Role of EUS in drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections not amenable for endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1107-19.

30. Giovannini M, Pesenti C, Rolland AL, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts or pancreatic abscesses using a therapeutic echo endoscope. Endoscopy. 2001;33:473-7.

31. Azar RR, Oh YS, Janec EM, et al. Wire-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage by using a modified needle knife and therapeutic echoendoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:688-92.

32. Kruger M, Schneider AS, Manns MP, Meier PN. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts or abscesses after an EUS-guided 1-step procedure for initial access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:409-16.

33. Baron TH. Drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: Is EUS really necessary? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1123-5.

34. Chahal P, Papachristou GI, Baron TH. Endoscopic transmural entry into pancreatic fluid collections using a dedicated aspiration needle without endoscopic ultrasound guidance: Success and complication rates. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1726-32.

35. Cahen D, Rauws E, Fockens P, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: Long-term outcome and procedural factors associated with safe and successful treatment. Endoscopy. 2005;37:977-83.

36. Aljarabah M, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic and endoscopic approaches for drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: A systematic review of published series. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1936-44. Epub 2007 Aug 24

37. Weckman L, Kylanpaa ML, Puolakkainen P, Halttunen J. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:603-7.

38. Papachristou GI, Takahashi N, Chahal P, et al. Peroral endoscopic drainage/debridement of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Ann Surg. 2007;245:943-51.

39. Kozarek RA. Endoscopic management of pancreatic necrosis: Not for the uncommitted. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:101-4.

40. Berzin TM, Mortele KJ, Banks PA. The management of suspected pancreatic sepsis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35:393-407.

41. Baron TH, Thaggard WG, Morgan DE, Stanley RJ. Endoscopic therapy for organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:755-64.

42. Baron TH, Morgan DE. Endoscopic transgastric irrigation tube placement via PEG for debridement of organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:574-7.

43. Raczynski S, Teich N, Borte G, et al. Percutaneous transgastric irrigation drainage in combination with endoscopic necrosectomy in necrotizing pancreatitis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:420-4.

44. Seewald S, Groth S, Omar S, et al. Aggressive endoscopic therapy for pancreatic necrosis and pancreatic abscess: A new safe and effective treatment algorithm (videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:92-100.

45. Charnley RM, Lochan R, Gray H, et al. Endoscopic necrosectomy as primary therapy in the management of infected pancreatic necrosis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:925-8.

46. Gardner TB, Chahal P, Papachristou GI, et al. A comparison of direct endoscopic necrosectomy with transmural endoscopic drainage for the treatment of walled off pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1085-94.

47. Baron TH, Harewood GC, Morgan DE, Yates MR. Outcome differences after endoscopic drainage of pancreatic necrosis, acute pancreatic pseudocysts, and chronic pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:7-17.

48. Park JJ, Kim SS, Koo YS, et al. Definitive treatment of pancreatic abscess by endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:256-62.

49. Venu RP, Brown RD, Marrero JA, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary drainage of pancreatic abscess: Technique and results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:391-5.

50. Harewood GC, Wright CA, Baron TH. Impact on patient outcomes of experience in the performance of endoscopic pancreatic fluid collection drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:230-5.

51. Nealon WH, Walser E. Surgical management of complications associated with percutaneous and/or endoscopic management of pseudocyst of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2005;241:948-57.

52. Evans KA, Clark CW, Vogel SB, Behrns KE. Surgical management of failed endoscopic treatment of pancreatic disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008 Aug 15. [Epub ahead of print]

53. Gullo L, Migliori M, Pezzilli R, et al. An update on recurrent acute pancreatitis: Data from five European countries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1959-62.

54. Brugge WR, Lauwers GY, Sahani D, et al. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1218-26.

55. Liu CL, Lo CM, Chan JK, et al. Detection of choledocholithiasis by EUS in acute pancreatitis: A prospective evaluation in 100 consecutive patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:325-30.

56. Levy MJ. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided Trucut biopsy of the pancreas: Prospects and problems. Pancreatology. 2007;7:163-6.

57. Elta GH. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and bile duct microlithiasis in acute idiopathic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1023-6.

58. Klein SD, Affronti JP. Pancreas divisum, an evidence-based review: Part I, pathophysiology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:419-25.

59. Kinney TP, Punjabi G, Freeman M. Technology insight: applications of MRI for the evaluation of benign disease of the pancreas. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:148-59.

60. Heyries L, Barthet M, Delvasto C, et al. Long-term results of endoscopic management of pancreas divisum with recurrent acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:376-81.

61. Chacko LN, Chen YK, Shah RJ. Clinical outcomes and nonendoscopic interventions after minor papilla endotherapy in patients with symptomatic pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 Apr 22. [Epub ahead of print]

62. Kwan V, Loh SM, Walsh PR, Williams SJ, Bourke MJ. Minor papilla sphincterotomy for pancreatitis due to pancreas divisum. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:257-61.

63. Delhaye M, Arvanitakis M, Bali M, et al. Endoscopic therapy for chronic pancreatitis. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:143-53.

64. Costamagna G, Bulajic M, Tringali A, et al. Multiple stenting of refractory pancreatic duct strictures in severe chronic pancreatitis: Long-term results. Endoscopy. 2006;38:254-9.

65. Kozarek RA, Brandabur JJ, Ball TJ, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients who undergo extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for chronic calcific pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:496-500.

66. Dumonceau JM, Costamagna G, Tringali A, et al. Treatment for painful calcified chronic pancreatitis: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus endoscopic treatment: A randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2007;56:545-52.

67. Guda NM, Partington S, Freeman ML. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy in the management of chronic calcific pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. JOP. 2005;6:6-12.

68. Howell DA, Dy RM, Hanson BL, et al. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic duct stones using a 10F pancreatoscope and electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:829-33.

69. Delhaye M, Arvanitakis M, Verset G, et al. Long-term clinical outcome after endoscopic pancreatic ductal drainage for patients with painful chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1096-106.

70. Rosch T, Daniel S, Scholz M, et al. Endoscopic treatment of chronic pancreatitis: A multicenter study of 1000 patients with long-term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2002;34:765-71.

71. Dite P, Ruzicka M, Zboril V, Novotny I. A prospective, randomized trial comparing endoscopic and surgical therapy for chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2003;35:553-8.

72. Cahen DL, Gouma DJ, Nio Y, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:676-84.

73. Devière J, Bell RHJr, Beger HG, Traverso LW. Treatment of chronic pancreatitis with endotherapy or surgery: critical review of randomized control trials. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:640-4.

74. Will U, Meyer F, Manger T, Wanzar I. Endoscopic ultrasound-assisted rendezvous maneuver to achieve pancreatic duct drainage in obstructive chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:171-3.

75. Tessier G, Bories E, Arvanitakis M, et al. EUS-guided pancreatogastrostomy and pancreatobulbostomy for the treatment of pain in patients with pancreatic ductal dilatation inaccessible for transpapillary endoscopic therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:233-41.

76. Andren-Sandberg A, Dervenis C. Pancreatic pseudocysts in the 21st century. Part I: classification, pathophysiology, anatomic considerations and treatment. JOP. 2004;5:8-24.

77. Zhang AB, Zheng SS. Treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts in line with D’Egidio’s classification. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:729-32.

78. Nealon WH, Walser E. Main pancreatic ductal anatomy can direct choice of modality for treating pancreatic pseudocysts (surgery versus percutaneous drainage). Ann Surg. 2002;235:751-8.

79. Baron TH. Endoscopic therapy with multiple plastic stents for benign biliary strictures due to chronic calcific pancreatitis: The good, the bad, and the ugly. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:96-8.

80. Catalano MF, Linder JD, George S, et al. Treatment of symptomatic distal common bile duct stenosis secondary to chronic pancreatitis: Comparison of single vs. multiple simultaneous stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:945-52.

81. Costamagna G, Bulajic M, Tringali A, et al. Multiple stenting of refractory pancreatic duct strictures in severe chronic pancreatitis: Long-term results. Endoscopy. 2006;38:254-9.

82. Kahaleh M, Behm B, Clarke BW, et al. Temporary placement of covered self-expandable metal stents in benign biliary strictures: A new paradigm? (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:446-54.

83. Levy MJ, Wiersema MJ. EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis and celiac plexus block. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:923-30.

84. LeBlanc J, DeWitt J, Johnson C, et al. A prospective randomized trial of 1 versus 2 injections during EUS-guided celiac plexus block for chronic pancreatitis pain. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:835-42.

85. Cicek B, Parlak E, Oguz D, et al. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic fistulas. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1706-12. Epub 2006 Sep 6

86. Costamagna G, Mutignani M, Ingrosso M, et al. Endoscopic treatment of postsurgical external pancreatic fistulas. Endoscopy. 2001;33:317-22.

87. Boerma D, Rauws EA, van Gulik TM, et al. Endoscopic stent placement for pancreaticocutaneous fistula after surgical drainage of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1506-9.

88. Bracher GA, Manocha AP, DeBanto JR, et al. Endoscopic pancreatic duct stenting to treat pancreatic ascites. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:710-15.

89. Cicek B, Parlak E, Oguz D, et al. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic fistulas. Surg Endosc. 2006.

90. Fischer A, Benz S, Baier P, Hopt UT. Endoscopic management of pancreatic fistulas secondary to intraabdominal operation. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:706-8.

91. Rabago LR, Ventosa N, Castro JL, et al. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative fistulas resistant to conservative management using biological fibrin glue. Endoscopy. 2002;34:632-8.

92. Wehrmann T, Riphaus A, Frenz MB, et al. Endoscopic pancreatic duct stenting for relief of pancreatic cancer pain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:1395-400.

93. Mauro MA, Koehler RE, Baron TH. Advances in gastrointestinal interventions: The treatment of gastroduodenal and colorectal obstructions with metallic stent. Radiology. 2000;215:659-69.

94. Kaw M, Singh S, Gagneja H, Azad P. Role of self-expandable metal stents in the palliation of malignant duodenal obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:646-650.

95. Jeurnink SM, van Eijck CH, Steyerberg EW, et al. Stent versus gastrojejunostomy for the palliation of gastric outlet obstruction: A systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:18.

96. Mutignani M, Tringali A, Shah SG, et al. Combined endoscopic stent insertion in malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction. Endoscopy. 2007;39:440-7.

97. Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: A report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330-6.

98. Gan SI, Thompson CC, Lauwers GY, et al. Ethanol lavage of pancreatic cystic lesions: initial pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:746-52.

99. Oh HC, Seo DW, Lee TY, et al. New treatment for cystic tumors of the pancreas: EUS-guided ethanol lavage with paclitaxel injection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:636-42. Epub 2008 Feb 11