64 Endoscopic Surgical Pain Management in the Aging Spine

KEY POINTS

Introduction

The aging spine typically begins with disc degeneration and annular dehiscence, followed by transfer of loads from the anterior spinal column to the facets. This may produce discogenic pain and axial back pain, resulting in segmental instability with resultant deformity. If the condition becomes painful, and nonsurgical treatment is not effective, traditional surgical treatment has been limited to diskectomy and fusion. Though diskectomy has been shown to be beneficial by the SPORT1 study, the long-term cost-effectiveness of fusion is questioned. Traditional spine surgery to treat painful degenerative disc disease such as with herniated discs, spondylolisthesis, central spinal stenosis, and neuroforaminal stenosis encompasses many different techniques. Surgical treatment, however, often results in a “failed back surgery syndrome” (FBSS) with limited success for subsequent salvage procedures. Newer minimally invasive techniques, in skilled and experienced hands, when approaching the pathology along natural muscle and tissue planes opens the door to earlier and a greater number of minimally invasive surgical options for the painful, aging spine without excessive concern about the paradoxical effects of surgery. The concept of “endoscopic surgical pain management” is addressed in this chapter, based on the senior author’s (ATY) 20-year experience using his percutaneous endoscopic transforaminal surgical technique described as the YESS (Yeung Endoscopic Spine Surgery) procedure.

The YESS procedure eliminates the pain generator causing the pain syndrome, not just “masking” the pain with therapeutic injections. The approach accomplishes disc decompression by “selectively” removing degenerative nucleus, sealing and closing annular tears, decompressing spinal nerves, ablating nerves and inflammatory tissue contributing to discogenic and axial back pain, and surgically removing a wide spectrum of disc herniations. In more advanced stages, lumbar spondylolysis and isthmic and degenerative spondylolisthesis can also be addressed surgically. This brief overview provides examples of conditions that the senior author has treated endoscopically with minimal surgical morbidity, in contrast with the much more invasive traditional option. The reader is directed to the published references for more detailed information on the evolution of this new minimally invasive and innovative technique.2–15

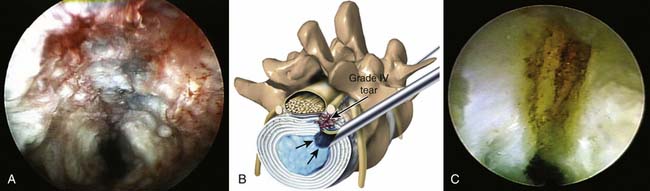

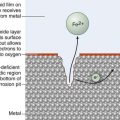

Traditional surgical correction in the aging spine usually involves open decompression, fixation, and fusion techniques. The percentage of fusion surgeries for these conditions as a whole has increased dramatically in the United States over the past few decades. Between 1990 and 2001, lumbar fusion surgery increased 220%.16 A recent article by Tosteson and colleagues,17 examining the data from the SPORT trial, concluded that even for degenerative spondylolisthesis surgery (decompression and fusion) is not a cost-effective procedure, when examined over a 2-year period. The importance of this data is that it emphasizes the need to better identify the source of back pain and sciatica, possibly earlier treatment, and more thorough study of the complex innervations of the spine in the foramen (Figure 64-1A-C). This area, known as the “hidden zone” of MacNab, holds the answer to the effectiveness of foraminal decompression and ablation of foraminal nerves in the treatment of discogenic and facet pain. It may have an impact on health care reform that seeks to reduce the cost of care, because over 100 billion dollars a year is spent on back pain in the United States, most of it being spent on nonsurgical treatment such as physical therapy, interventional pain management, and over-the-counter and prescription drugs. We also need to reduce the need for fusion as a surgical solution for pain. This can be accomplished if we are able to not only demonstrate the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of endoscopic surgical pain management, but help establish a new subspecialty in endoscopic surgical pain management, because it requires special training to acquire proficiency.

Understanding chronic, surgically treatable back pain begins with understanding common lumbar pain. Cadaver microdissection of the nerves in the foramen reveals an extensive network of nerves arising from the spinal cord, splitting into the dorsal and ventral rami before exiting the foramen as the spinal nerve. A ramus communicans connects with the sinuvertebral nerves innervating the annulus. When there is an inflammatory response to annular tears with the development of an inflammatory membrane, the subsequent neo-neurogenesis and angiogenesis response contributes to pain that is not detected by imaging studies currently available. Better soft tissue imaging and imaging of chemical changes in the spine may help. We traditionally only grossly see the traversing and exiting spinal nerves as surgeons, and routinely fail to recognize and miss the relatively common furcal nerve, or the dorsal ramus and its medial and lateral branches that emanate from each spinal nerve. This network of nerves from the dorsal ramus contributes greatly to chronic discogenic and axial back pain not responsive to nonsurgical treatment. It is undetected by MRI or CT scan, but can be visualized endoscopically and confirmed by meticulous cadaver dissection (Figure 64-1B, C). Rational treatment calls for the appropriate and effective use of diagnostic and therapeutic diagnostic procedures such as diskography, selective nerve root blocks, foraminal epidural steroid blocks, facet and medial branch blocks, and sympathetic nerve blocks. Research studies, such as those by Caragee18, that emphasize the risks and the difficulty of interpretation of diagnostic tests such as diskography without balancing the indications and usefulness of the diskography, does a disfavor to endoscopic minimally invasive surgeons who are able to look at pathoanatomy and are skilled at spinal endoscopy. This skill affords endoscopic surgeons the opportunity to treat lumbar pain and sciatica without fusion.

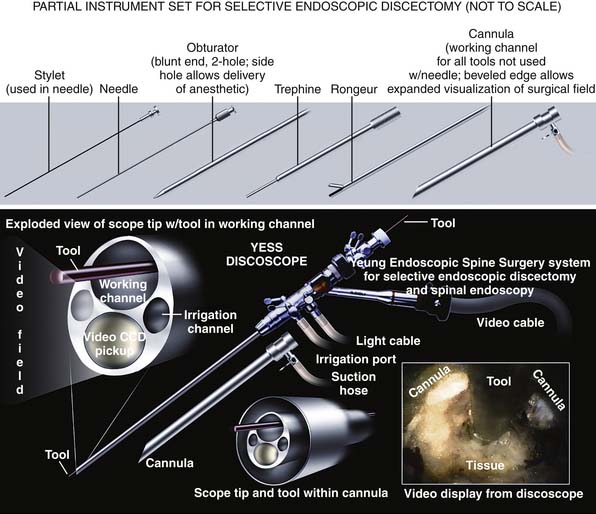

Description of the Device

The design of the endoscope and endoscopic system is an important factor for endoscopic surgeons to consider. Techniques of endoscopic decompression vary depending on the endoscope design, the available surgical instruments, and surgical techniques practiced by the developer of the system. Not all endoscopic systems are designed for or amenable to the technique described here, but techniques and endoscopic systems continue to evolve. This chapter specifically describes the YESS transforaminal “inside-out-technique,” utilizing the YESS foraminoscope (Figure 64-2) and the instruments designed for the system and technique. Not only is it important to have the necessary instruments, but specially configured cannulas are designed to expose the pathoanatomy to be surgically treated but, in the process, also protect vital anatomy such as the nerve and dura. Other systems are also evolving, so that in time, there will be similarities evolved and copied from the YESS transforaminal technique illustrated here.

Background of Scientific Testing and Clinical Outcomes

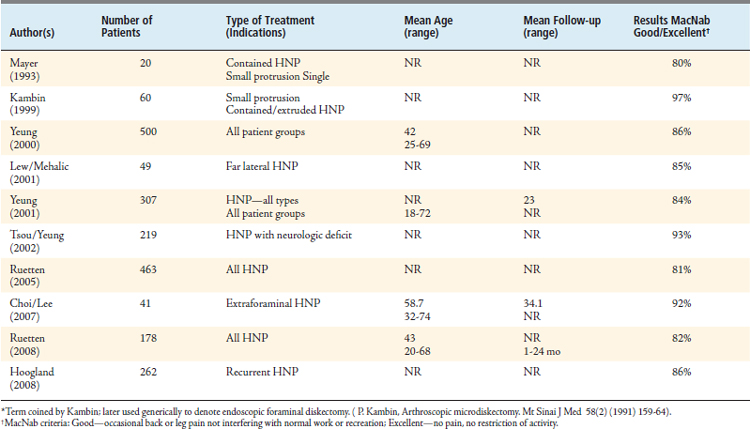

Peer-reviewed literature for disc herniation, first reported by Mayer and Brock19 in 19933 then by Hermantin2 in a prospective randomized study, has concluded that the results with transforaminal endoscopic (coined “arthroscopic” by Kambin20) diskectomy in the lumbar spine are generally similar to those with open diskectomy, but with significantly less surgical morbidity and quicker recovery (Table 64-1). The YESS technique evolved from the original Kambin technique as Yeung originally learned from Kambin. The procedure, done on an outpatient basis, utilizes local anesthesia with sedation. Patients are usually discharged an hour after surgery. Results show that patients use less postoperative pain medication and return to work within 1 to 6 weeks. It is not unusual for individual patients to return to work in a matter of days. Long-term follow-up has demonstrated decreased recurrence (6%), less postlaminectomy syndrome, and greater patient satisfaction overall. Morganstern, a student of Yeung21, has reported6 that after a learning curve of approximately 70 patients utilizing the YESS technique for a wide spectrum of disc herniation types, a 90% overall good/excellent result by MacNab and modified MacNab criteria is achievable. The 90% standard was the goal established for endoscopic surgeons wishing to take up the procedure. The results for all types of herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP), through 2008, as reported in the literature are summarized in Table 64-2.

| Level II-III Evidence | SURGICAL OUTCOME | |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Arthroscopic Microdiskectomy | Group 2: Microscopic Diskectomy | |

| Satisfactory outcome | 97% | 93% |

| “Very satisfied” | 73% | 67% |

| Disability | 27 days | 49 days |

| Narcotic use | 7 days | 25 days |

| Hospital stay | 0 day | 1 day |

∗ Sixty patients randomized, 30 per group.

From F.U. Hermantin,T. Peters, L. Quartararo, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing the results of open discectomy with those of video-assisted arthroscopic microdiscectomy. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 81A ( 1999 ) 958 – 965.

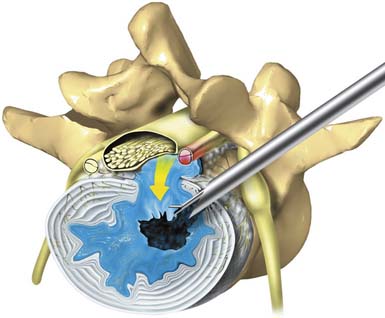

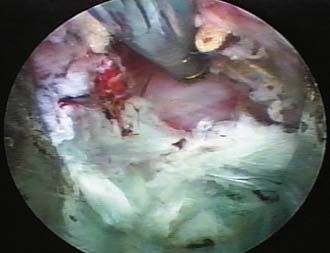

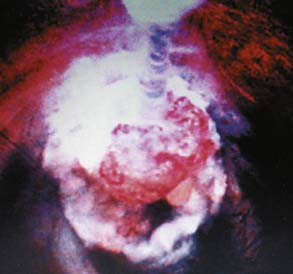

The endoscopic foraminal approach, differentiated from the posterior approach, emphasizes the dilation along tissue planes without damage to normal anatomy. The foraminal approach for disc herniation utilizing the “inside-out-technique” provides easy access for central, paracentral, and subligamentous foraminal and extraforaminal disc herniations through natural tissue planes between the longissimus and psoas muscles (Figure 64-3). For foraminal and large paracentral herniations, it is easy to visualize the lateral edge of the traversing nerve (Figure 64-4) once the herniation is removed. If the fragment is large and extruded, it comes out as an intact collagenized fragment. Prodromal symptoms of disc herniation in the aging spine usually arise from annular tears, which cause recurrent back pain and sciatica before the disc herniates. The opportunity to study and treat painful annular tears endoscopically that do not heal naturally provides information on validating the theory of electrothermal therapy but also sheds light on the reasons why the usefulness of blind radiographic methods will always be limited. Identification of granulation tissue and nucleus material in the annular layers (Figure 64-5A) provides a good prognosis for those tears treated with thermal annuloplasty. The nucleus material that weakens the annulus must be removed before the annulus is cauterized to close the tear. Using a biportal approach and a 70-degree scope, cauterization and confirmation of successful thermal annuloplasty under direct endoscopic visualization provide confirmation that the tear is closed and sealed (Figure 64-5B).

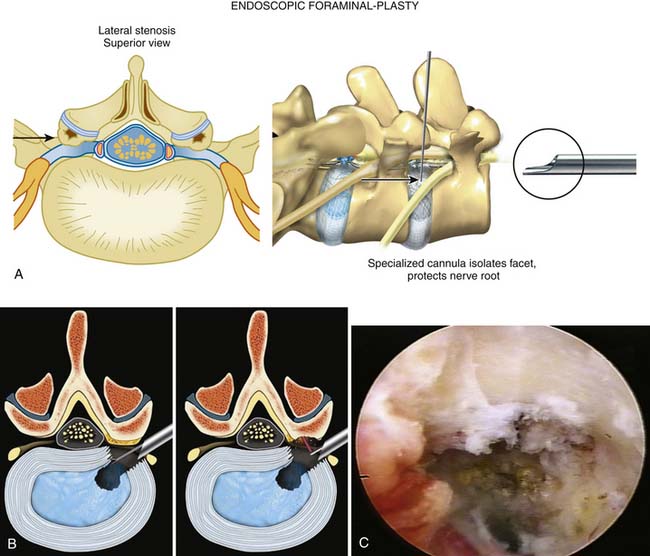

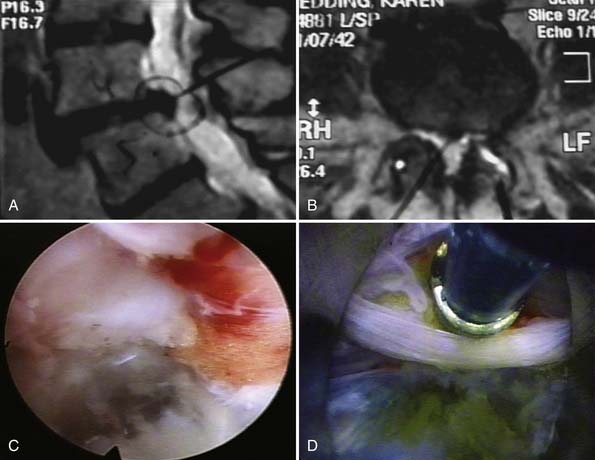

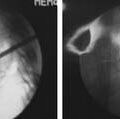

The technique for endoscopic foraminoplasty in more advanced disc degeneration and foraminal narrowing is associated with central and foraminal stenosis, not only for lateral recess stenosis but also for foraminal decompression of the ventral facet in tall discs to gain “inside-out” access to sequestered herniations in the epidural space. A foraminoplasty cannula exposes the ventral aspect of the superior facet for endoscopic decompression (Figure 64-6A), which helps strip the capsule and define the undersurface of the facet to be removed with trephines and burrs (Figure 64-6B). Degenerative spondylolisthesis is often associated with disc protrusions and lateral stenosis, whereas sciatica from isthmic spondylolisthesis, due to the mechanical compression of the axilla and subarticular recess (Figure 64-6C), is effectively treated by endoscopic foraminal decompression in selected patients. These patients usually improve temporarily with foraminal diagnostic and therapeutic injections. Endoscopic decompression of the foramen can provide enough relief that the patient will avoid fusion. Failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) patients with lateral recess stenosis and recurrent disc herniation also respond well. When the support is shifted posteriorly to the facet joints, synovitis and facet cysts may form. These cysts may impinge on the spinal nerves. Pedunculated cysts are sometimes visualized endoscopically, especially if the cyst wall is stained by indigo carmine or is visualized in the course of a diskectomy for chronic sciatica (Figure 64-7). Degenerative and isthmic spondylolisthesis (Figure 64-8A-D) can also be treated endoscopically with proper interventional injection workup. Impingement from the disc or superior facet of the inferior vertebra can be sorted out with diagnostic and therapeutic injections. If evocative diskography evokes concordant back pain and/or sciatica, and foraminal epiduralgrams and therapeutic injections provide information of the pathoanatomy, then careful preoperative planning will provide information on the likely outcome of foraminal decompression.

Operative Technique(s)

Procedure

The procedure and technique described are those preferred by the author. In every instance, diskography is an integral part of the technique. The diagnostic value of the subjective provocative response is valuable for confirming the disc as the source of the pain. Not only is evocative Chromo-Discography a clinical confirmatory test that links the suspected painful disc to the patient’s subjective pain complaints, but the blue staining of the degenerated nucleus pulposus and annular defects, using the vital dye indigo carmine in 10% concentration, visually identifies normal and degenerative portions of the disc and annulus in contained or uncontained herniations. Contiguous disc fragments in the epidural space, disc tissue embedded in the annular defects, and herniation tracts are stained by the dye for targeted removal. Nonionic Isovue 300 contrast is used for radiographic visualization of the injectate. It is mixed with indigo carmine in a 10:1 ratio. In a nondegenerated disc, the roentgenographic contrast permeates the nucleus pulposus and forms a compact oval or bilobular nucleogram. There is no dye penetration into the substance of the normal impermeable annular collagen layers. Therefore the absence of an annulogram represents a normal annulus. In degenerated conditions, clefts, crevices, tears, and migrated fragments of nucleus will be filled with contrast both inside the disc and along the herniation tract.

The endoscopic approach uses a posterolateral approach, located typically 10 to 12 cm from the midline of the spine in a 160- to 180-pound patient, and uses an access cannula with 6- to 7-mm inner diameter and 7- to 8-mm outer diameter. It allows for the use of foramimal endoscopes with 2.8-, 3.1-, and 4.0-mm working channels that provide excellent, clear visualization of and access to the foraminal structures containing the disc and annulus, the epidural space, and ventral surface of the facet joint, including the pedicle and vertebral body. A combination of trephines, Kerrison rongeurs, high-speed drills, articulating graspers, flexible pituitary graspers, and various laser delivery systems can be used to ablate nerves, enlarge the neural foramen, remove facet and foraminal osteophytes, and decompress the spinal canal compressing neural structures without any destruction of the posterior spinal structures. Foraminal decompression is capable of treating a treating a wide variety of the pathologies discussed here. Its application potential in the elderly is virtually limitless, as it allows for outpatient and minimally invasive treatment of many spine disorders currently managed with either large, open surgeries or pain medications alone. The emergence of foraminal spinal endoscopy offers a bridge for treating many spinal ailments in patients who might not fare well with large open surgeries yet need something more than pain management.

Complications and Avoidance

The risk of serious complications or injury is low—approximately 1% or less in the authors’ experience. As with any surgery, there are the usual risks of infection, nerve injury, dural tears, bleeding, and scar tissue formation. Transient dysesthesia, the most common postoperative complaint, occurs in approximately 5% to 15% of cases and is almost always transient. Its cause remains incompletely understood, but a detailed study of foraminal anatomy reveals an extensive network of nerves that can be surgically irritated, even with the most careful use of surgical instruments. Dysesthesia may also be related to nerve recovery, operating adjacent to the dorsal root ganglion of the exiting nerve, or a small hematoma adjacent to the ganglion of the exiting nerve, because it can occur days or even weeks after surgery. There are also anomalous nerve fibers in the annular tissue, which may be furcal nerves or

nerves growing into an inflammatory membrane in the area of the foramen that is not the traversing or exiting nerve. It could show up in the surgical specimen without permanent effect on the patient, but may cause temporary dysesthesia. Using blunt techniques to dilate the annular fibers has limited surgical morbidity and the excisional biopsy of tissues (anomalous nerves) caused by neo-neurogenesis and angiogenesis from the surgical specimen, but dysesthesia cannot be avoided completely, because it has occurred even when there were no adverse intraoperative events and in cases in which the continuous electromyography (EMG) and somatosensory evoked potentials (SEP) did not show any nerve irritation. The symptoms are sometimes so minimal that most endoscopic surgeons do not report it as a “complication.” The more severe dysesthetic symptoms are similar to a variant of complex regional pain syndrome, but usually less severe, and without the skin changes. Postoperative dysesthesia is treated with transforaminal epidurals, sympathetic blocks, and the off-label use of pregabalin 150 mg/day or gabapentin titrated to as much as 1800 to 3200 mg/day. Gabapentin is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for postherpetic neuralgia, but is effective in the treatment of neuropathic pain. The close proximity of sympathetic nerves and their role in disc innervation is still poorly understood, but treatment of dysesthesia by blocking the sympathetic trunk has produced dramatic results, especially when provided early in the course of postoperative dysesthesia.

1. Weinstein J.N., Tosteson T.D., Lurie J.D., Tosteson A.N., Hanscom B., Skinner J.S., et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2441-2450.

2. Hermantin F.U., Peters T., Quartararo L., Kambin P. A prospective, randomized study comparing the results of open discectomy with those of video-assisted arthroscopic microdiscectomy. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1999;81A:958-965.

3. Yeung A.T. Minimally invasive disc surgery with the Yeung Endoscopic Spine System (YESS). Surg. Technol. Int.. 2000;VIII:267-277.

4. Yeung A.T., Tsou P.M: Posterolateral endoscopic excision for lumbar disc herniation: surgical technique, outcome, and complications in 307 consecutive cases, Spine, 27:722-731, 2002.

5. Tsou P.M., Yeung A.T. Transforaminal endoscopic decompression for radiculopathy secondary to intra-canal non-contained lumbar disc herniations: outcome and technique. Spine J.. 2002;2:41-48.

6. Yeung A.T., Yeung C.A. Advances in endoscopic disc and spine surgery: foraminal approach. Surg. Technol. Int.. 2003;XI:253-261.

7. Tsou P.M., Yeung C.A., Yeung A.T. “Selective endoscopic discectomy™ and thermal annuloplasty for chronic lumbar discogenic pain: a minimal access visualized intradiscal procedure”. Spine J.. 2004;2:563-574.

8. Yeung, M.H. Savitz A.T., Khoo L.T., et al. Complications of minimally invasive spinal procedures and surgery Part IV: percutaneous and intradiscal techniques. In: Vacarro A.R., Regan J.J., Crawford A.H., et al, editors. Complications of pediatric and adult spinal surgery. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004:547-571.

9. Yeung A.T., Yeung C.A. Percutaneous foraminal surgery: the YESS technique. In: Kim D., Fessler R., Regan J., editors. Endoscopic spine surgery and instrumentation. New York: Thieme, 2005.

10. Yeung A.T., Yeung C.A. In vivo endoscopic visualization of patho-anatomy in painful degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine. Surg. Technol. Int. XV. 2006:243-256.

11. Yeung A.T., Yeung C.A. Microtherapy in low back pain. In: Mayer H.M., editor. Minimally invasive spine surgery. second ed. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 2006:267-277.

12. Kauffman C., Yeung C.A., Yeung A.T: Percutaneous lumbar surgery. In Rothman Simeone, Herkowitz H.N., Garfin S.R., Eismont F.J., Bell G.R., Balderston M.D. The spine, 5th edition, Philadelphia: Elsevier/ Mosby Saunders, 2006.

13. Yeung A.T. Incorporating adjunctive minimally invasive surgical technologies in endoscopic foraminal surgery: one surgeon’s experience with endoscopic treatment of painful degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine. SAS J. 2007.

14. Yeung A.T., Yeung C.A. Minimally invasive techniques in the management of lumbar disc herniation. Orthop. Clin. North Am.. 2007;38(3):363-372.

15. A. Yeung, C.A. Yeung, Arthroscopic lumbar discectomy, in: advanced reconstruction: spine, American Academy of Orthopedic surgeon publication, Chicago, Illinois Publication Project 2009 (in Press)

16. Martin B.I., Mirza S.K., Comstock B.A., et al. Reoperation rates following lumbar spine surgery and the influence of spinal fusion procedures. Spine. 2007;32(3):382-387.

17. Tosteson A.N.A., Lurie J.D., Tosteson T.D., et al. Surgical treatment of spinal stenosis with and without degenerative spondylolisthesis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;149(12):845-854.

18. Caragee E.J. Is Lumbar discography a determinate of discogenic low back: Provocative discography reconsidered: current Pain and Headache Reports. 2007;4:301-308.

19. Mayer H.M., Brock M. Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy (PELD). Neurosurg Rev. 1993;16(2):115-120.

20. Kambin P., Nass. Arthroscopic Microdiscectomy. Spine Journal. 2003;3(Suppl. 3):60S-64S. (Review)

21. Tsou P.M., Yeung A.T. Transforaminal endoscopic decompression for radiculopathy secondary to intracanal noncontained lumbar disc herniations: outcome and technique. Spine Journal. 2002;2(1):41-48.

22. Kambin P. Arthroscopic microdiskectomy. Mt Sinai J Med. 1991;58(2):159-164.