CHAPTER 15 Endoscopic mid and lower face rejuvenation

History

The concepts and principles for the endoscopic midface procedure currently employed began in the 1980s when plate fixation for zygomatic fractures was introduced. These plates necessitated wide subperiosteal stripping for exposure and fixation. Postoperatively, patients developed significant soft tissue ptosis that was ascribed to this extensive dissection without adequate soft tissue suspension. Since these plates were to be removed at a second stage, resuspension of the soft tissues through a subperiosteal dissection was subsequently carried out at that time. To our surprise we failed to restore the preoperative aesthetics through this approach. In some instances there was excess bunching and fullness in the lower lid necessitating removal of substantial amounts of lower lid skin and orbicularis oculi muscle that ultimately resulted in very unpredictable lower lid outcomes. Suffice it to say that the final outcome on the operated side seldom succeeded in achieving aesthetic symmetry with the normal unoperated side.

These disappointing results prompted a fresh cadaver anatomic study of a supraperiosteal approach specifically aimed at remaining above the zygomaticus major muscle and below the orbicularis oculi muscle. This approach had the advantage of mobilizing the orbicularis oculi muscle, malar fat pad, and high SMAS as a composite unit while avoiding the downward force of the zygomaticus major muscle by leaving its origin attached to the bone. This anatomic approach was adopted as an aesthetic procedure and was reported in the 1990s as an extended temporal lift.1 It reached its full aesthetic value as an endoscopic procedure in the late 1990s where motor innervation to the lower eyelid was further defined and precise suture fixation of the orbicularis muscle identified in a manner that allowed correction of most lower lid problems.2,3 Complete with this evolution of facial aesthetics was the simultaneous recognition that the midface procedure necessitated adjustments in lower facial rejuvenation that emphasized the neck and jawline, and at the same time eliminated the lateral sweep deformity as described by Hamra.3

Physical evaluation

• Upper lid fullness corrected at least in part by brow repositioning.

• A widened malar-orbicular crescent.

• A deepened tear trough and malar groove.

• An accentuated lid/cheek junction.

• Improved aesthetics with two point elevation of the lateral brow and malar complex.

Anatomy

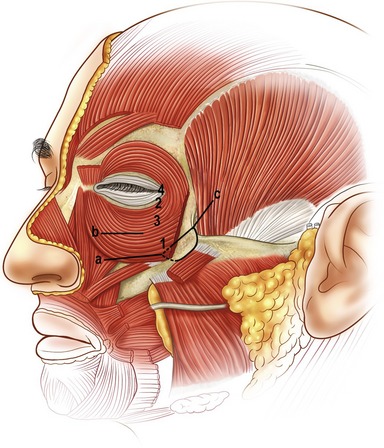

A key goal in the forehead and midface portion of this procedure is the mobilization and release of the orbicularis oculi muscle from the orbit. The release is above rather than below the periosteum. We feel this obtains more shaping of the brow and an effective shift of the preseptal upper lid orbicularis, which eliminates the need for upper eyelid muscle resection. Critical to the mobility of the orbicularis oculi muscle is the release of the preseptal muscle from its attachments to the orbital rim. In the lower lid this attachment has been identified as the zygo-orbicular ligament.3 Laterally this same attachment along the outer rim surface represents the superficial head of the lateral canthus, while in the upper lid fusion between the orbit and orbicularis is anatomically similar to that described in the lower eyelid. This zone of fusion serves as a retaining structure to the brow.4 The selective release, mobilization, and fixation of these retaining structures of the orbicularis oculi muscle are important to achieving the desired periorbital aesthetics. Precise suture placement in the four target zones of the orbicularis oculi muscle allows lower lid shaping and control based on the requirements of the lid morphology (Fig. 15.3).

A second key in achieving the desired aesthetic relationship between the midface and lower eyelid depends on the release and mobilization of the malar retaining ligament.5 This ligament consists of a dime-sized zone of fibrous attachments extending from the periosteum of the zygomatic eminence to the subcutaneous tissue of the cheek. The lateral and most dense portion of this ligament arises from the lateral border of the zygoma where the masseter muscle attaches. Fibers continue through the origin of the zygomaticus major muscle and extend superficially through the malar fat pad and lateral border of the orbicularis oculi muscle (Fig. 15.4). By releasing these fibers above the zygomaticus major muscle, the midface can be moved vertically, eliminating the downward force of the zygomaticus muscle that is typically produced in a subperiosteal approach. The anatomic components of this midface movement include the orbital portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle, the malar fat pad, and the upper or high SMAS.

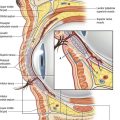

The third anatomic key of the eyelid midface procedure is the sparing of the orbicularis oculi muscle. This is achieved by avoiding: muscle division, muscle resection, and muscle denervation. The motor innervation to the lower lid orbicularis not only arises medially from the zygomatic branch running deep to the zygomaticus major muscle, but also laterally from branches arising from the zygomatic branch before it passes beneath the zygomaticus major muscle6 (Fig. 15.5). These lateral branches enter the inferior lateral belly of the orbicularis muscle. While the medial innervation is integral to the blink reflex, the lateral innervation is equally important to lower lid pretarsal muscle tone. It is for this reason that transpalpebral division of the orbicularis muscle is avoided and a transconjunctival approach is used when access to fat or the septum is needed.

The relevant anatomy to lower facial rejuvenation hinges on the mobilization and fixation of the structures previously described. The important fact to be recognized is that the upper or high SMAS movement has already occurred. Hence, when dealing with the lower face, a skin only or low SMAS skin procedure is indicated. The vector of the low SMAS or skin procedure is placed in a lateral direction along the jawline. Emphasizing a strong jawline vector while avoiding the additional lateral tension on the high SMAS, avoids the tightening and the flattening of the malar remnants with the creation of submalar traction lines that have been referred to as “lateral sweep.”7 In the majority of patients who have significant lower facial laxity my preference is a separate skin and SMAS flap procedure. The SMAS is elevated in continuity with the platysma muscle so that a strong lateral vector SMAS-platysma pull is achieved along the jawline (Fig. 15.6). The skin is closed with minimal preauricular tension. The lateral vector SMAS platysma movement generally fails to provide adequate tension in the submental area from the hyoid to the mandible. A medial plication in this zone is usually incorporated. Platysma muscle division is reserved for banding and for very obtuse necks.

Technical steps

Markings and incisions

Markings for the forehead include a vertical brow vector placed at the junction of the medial  and lateral

and lateral  of the brow. A point for frontalis muscle fixation is marked along this vector where the vertical forehead begins to slope cephalad. The vector for malar and midface lift is marked across the zygomatic eminence and extends from the nasalolabial folds temporally. Tear trough and malar groove depressions are marked, as well as areas of jowl fullness, submental fullness, and platysmal banding. The temporal brow-midface incision is marked in a coronal orientation in the temporal scalp about 2 cm into the hairline and 4 cm in length. An additional 3 cm midline incision is marked in the hairline of patients who need corrugator release or frontalis scoring. Lower face and neck incisions follow a retrotragal path around the ear and are extended in the postauricular scalp to provide access to the neck. Submental incisions are marked in the submental crease when needed.

of the brow. A point for frontalis muscle fixation is marked along this vector where the vertical forehead begins to slope cephalad. The vector for malar and midface lift is marked across the zygomatic eminence and extends from the nasalolabial folds temporally. Tear trough and malar groove depressions are marked, as well as areas of jowl fullness, submental fullness, and platysmal banding. The temporal brow-midface incision is marked in a coronal orientation in the temporal scalp about 2 cm into the hairline and 4 cm in length. An additional 3 cm midline incision is marked in the hairline of patients who need corrugator release or frontalis scoring. Lower face and neck incisions follow a retrotragal path around the ear and are extended in the postauricular scalp to provide access to the neck. Submental incisions are marked in the submental crease when needed.

Midface dissection

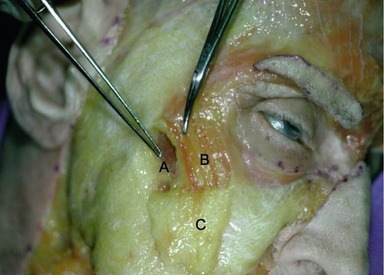

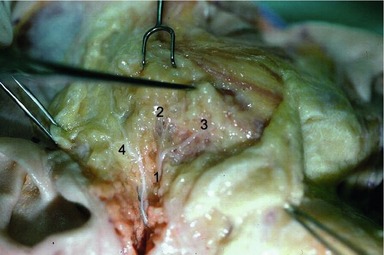

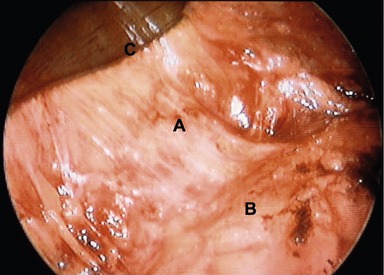

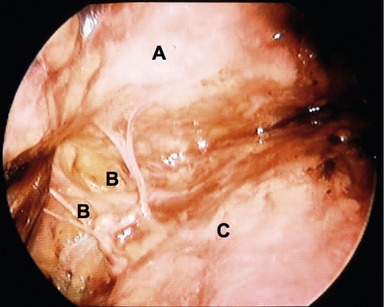

Access to the midface is obtained by extending the brow dissection over the superficial temporalis muscle fascia, deep to the temporoparietal and innominate fascia. At the level of the sentinel vein the superficial temporal muscle fascia is scored so as to bifurcate the fascia establishing a plane that is followed down to the zygomatic arch. A medial to lateral dissection extending from the lateral rim out across the temporalis fascia is employed. Dissection follows the lateral rim and superior margin of the zygomatic arch. At the junction of the lateral one-third and medial two-thirds of the arch, a one-centimeter subperiosteal tunnel is developed over the arch. The periosteum is incised laterally and then dissection is extended medially over the arch above the periosteum until the infraorbital rim is encountered. The reason for elevating the small subperiosteal tunnel is to create a point of anchorage along the course the temporal branch of the facial nerve so as to avoid traction injury on the nerve when the midface is mobilized vertically. Dissection along the infraorbital rim continues in the suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF) beneath the orbicularis oculi muscle. The zygo-orbicular ligament, which connects the preseptal orbicularis muscle to the infraorbital rim is visualized and released (Fig. 15.7). This release spans 8–10 mm and completely liberates the orbicularis at the lid–cheek junction. If excess orbital lid fat is present or if the orbital septum is lax, a transconjunctival preseptal dissection is performed. This connects the plane established by the midface dissection. The mobilized midface facilitates exposure to the fat compartments and orbital septum allowing fat removal and/or septal reset when required. The dissection then extends above the zygomaticus major muscle passing through the malar retaining ligament. Vertical spreading with tenotomy scissors disrupts these strong connective tissue attachments and spares the branches to the lateral orbicularis oculi muscle arising vertically from the zygomatic branch of the facial nerve (Fig. 15.8). The majority of these nerve branches are seen immediately lateral to the zygomatic major muscle. When the malar retaining ligament has been completely released, significant mobility of the midface is achieved. Structures moved are the lateral portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle, the malar fat pad, and the high SMAS. To fix these structures, a single suture of 4-0 clear nylon is passed through the cephalic portion of the malar retaining ligament and anchored to the superficial temporal fascia just lateral to the lateral orbital rim. This single suture is all that is required in the majority of patients. Additional orbicularis oculi sutures are used to shape the lower lid when required. When scleral show or lid laxity is present, a 5-0 clear nylon is placed in the pretarsal muscle and fixed to the deep head of the lateral canthal tendon. In the presence of a proptotic globe or negative vector orbit, a suture is placed in the orbital portion of the orbicularis muscle and sutured directly cephalad along the infraorbital rim. This vertical movement of the orbicularis elevates the lid and eliminates “clothes lining” of the lid that can occur with a traditional canthopexy. The final suture variation involves direct release of the deep head of the lateral canthal tendon and repositioning cephalad. This maneuver is reserved for patients with true canthal malposition and has only been required in 3% of patients. Lower eyelid skin is only removed if significant bunching is created with an approximate 2–3 mm excess. A Croton Oil peel may be applied for minor lower eyelid skin excess or crêpey skin. Commonly, micro-fat grafting is performed in the malar groove, nasolabial folds and lateral malar depression to blend any hollowing created by the vertical lift of the midface. The fat is harvested from an abdominal source at the beginning of the procedure and prepared for injection during the midface and brow dissection. Approximately 0.5 to 1 mL of fat is injected into the malar groove, 2 to 3 mL into the lateral malar area, and 2 mL into the nasolabial folds. A small 7 mm perforated round drain is placed in the temporal incision and extends into the malar dead space.

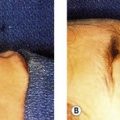

Lower face and neck

The endoscopic brow midface procedure has minimal effect on jawline laxity and no effect on the neck. To combine correction of the lower face and neck with the midface procedure, a retrotragal preauricular incision is carried around the postauricular sulcus to the level of the tragus. This is then extended posteriorly in a curvilinear manner into the hair-bearing scalp. A separate skin and SMAS flap is elevated (refer to Fig. 15.6). Skin dissection varies but generally extends to the midcheek and jawline area, whereas in the neck it extends across the midline. The SMAS is elevated in continuity with the platysma and is elevated across the parotid until the mobile SMAS is encountered. Platysmal elevation stops at the approximate level of the thyroid cartilage. The superior edge of SMAS elevation goes only to the tragus. It is important to avoid extending the SMAS dissection to a high SMAS plane over the arch. This will avoid disruption of the SMAS previously mobilized with the endoscopic procedure. The SMAS and platysma are grasped at the level of the inferior part of the jawline and at the superior edge of SMAS dissection and pulled laterally. Generally 1 to 2 cm of SMAS excess is resected. At the level of the jawline the resected margin of the platysma is sutured to the fixed mastoid fascia with a 4-0 Mersiline® suture (Ethicon, Inc. Somerville, NJ). Similarly the free edge of the superior portion of the SMAS is anchored to the fixed portion of the SMAS immediately in front of the tragus. With these two points of fixation, the remainder of the SMAS and platysma is sutured with a running 4-0 Mersiline® suture (Ethicon, Inc. Somerville, NJ) from its inferior border to superior edge of the SMAS.

If neck banding or an obtuse neck angle is present the inferior edge of the platysma at the level of the thyroid will be divided and advanced laterally and then reapproximated along its line of division. This reapproximation of the platysma avoids window shading along the area of division and creates a vertical elevation of the lateral and inferior neck. When redundancy or banding is seen in the central neck, a 3 cm submental incision is placed 2 mm inferior to the crease with wide dissection performed above the platysma in continuity with the lateral skin. Medially, plication of the platysma from the level of the hyoid to the inferior edge of the mandible is accomplished with 4-0 Mersiline® sutures (Ethicon, Inc. Somerville, NJ). Excess preplatysmal fat is removed, but only cautious removal of subplatysmal fat is carried out so as to avoid over accentuation of the central neck and exposure of the digastric muscle and submandibular gland. Fibrin glue may be sprayed subcutaneously in males and/or hypertensive patients. The skin incisions are closed by placing all tension on the retroauricular incision and leaving a tension-free preauricular incision. By extending the retroauricular incision into the hair-bearing scalp as an arc, a lateral and superior advancement of the neck flap can be carried out that allows realignment of the hairline and vertical elevation of the lateral neck. This adjustment minimizes the occurrence of plication folds of the posterior neck when direct lateral advancement is carried out. A 10 mm drain is placed through the posterior scalp incision and left overnight to drain the neck.

Postoperative care

When the endoscopic brow midface procedure is done as a stand-alone procedure, an elastic band is placed around the forehead providing light compression and a way to hold the hemovac drains that were placed through the temporal incision. When the procedure is combined with a low SMAS neck procedure, a conventional facelift dressing which pads the neck and cheek area is employed. All patients receive 8 mg of Decadron® IV (Abraxis Pharmaceutical Products, Schaumburg, IL, USA) at the initiation of the procedure and are placed on a tapering dose pack that extends out to five days. All patients receive prophylactic antibiotics for 3–5 days. Drains are left in for 12–24 hours. A lighter dressing compressing the neck/jawline is reapplied. The dressing is removed at the time of suture removal on day 5–7. An elastic neckband is worn at night for the next 5 days or until bruising has resolved. Makeup generally begins on the 10th day. Most patients return to work in two weeks, but are advised that they will have tightness and excess lateral canthal tension out to three weeks postoperatively.

Complications

Criticisms and downsides

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Better shaping, repositioning, and control of the brow and midface is achieved in and above the periosteum dissection.

• The midface and brow require careful endoscopic release of multiple anatomic regions for adequate correction of the aging face.

• After release of these regions, the correction relies on suture fixation of key points in the midface and brow.

• The zygo-orbicular ligament acts as the lower eyelid retaining ligament.

• The malar retaining ligament is released superficial to the zygomaticus major muscle.

• The SMAS and platysma can be elevated as a composite flap with lateral vector fixation for the correction of lower facial and neck aging.

Pitfalls

• Superficial dissection in the lateral temporal region may injure the frontal nerve branches; therefore the deep temporal fascia should be bisected at the sentinel vein to maintain a safe deep dissection plane.

• The release of the brow retaining ligaments in previously operated upper eyelids and in patients with pre-existing dry eye may lead to postoperative lagophthalmos and aggravation of dry eye.

• The deep head of the lateral canthus can be disrupted in the lateral periorbital dissection; therefore it should be identified and preserved.

• Motor nerve branches to the orbicularis oculi muscle arising lateral and medial to the zygomaticus major muscle should be preserved during release of the malar retaining ligament.

• A high SMAS dissection will disrupt the vertical midface fixation; therefore only a low SMAS dissection is necessary when combined midface, brow and neck procedures are performed.

Summary of steps

2. Endoscopic deep temporal fascial dissection: sentinel vein identification and bisection of the temporal fascia.

3. Zygo-orbicular ligament and malar retaining ligament release.

4. Midface elevation and suture fixation.

5. Brow dissection in supraperiosteal plane with selective: superior brow retaining ligament release, corrugator cauterization and galeal scoring.

6. Brow fixation with galeal cable suture, dermal repositioning and temporal flap fixation.

8. Selective lower eyelid procedure.

9. Retrotragal incision, subcutaneous neck and face dissection with sub-SMAS and platysmal dissection.

10. Low SMAS flap with lateral vector.

1. Byrd HS, Andochick SE. The deep temporal lift: a multi-linear lateral brow, temporal and upper face lift. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97(5):928.

2. Byrd HS, Salomon J. Endoscopic midface rejuvenation. In: Culbertson JH, ed. Operative techniques in plastic surgery. Philadelphia: WG Saunders; 1998:138–144.

3. Byrd HS. Achieving aesthetic balance in the brow, eyelids and midface. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(3):926.

4. Sullivan PK, Salomon JA, Woo AS, Freeman MB. The importance of the retaining ligamentous attachments of the forehead for selective eyebrow reshaping and forehead rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(1):95–104.

5. Mendelson BC, Muzaffar Arshad R, Adams WP, Jr. surgical anatomy of the midcheek and malar mounds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(3):885–896.

6. Lowe JB, III., Cohen M, Hunter D, Mackinnon SE. Analysis of the nerve branches to the orbicularis oculi muscle of the lower eyelid in fresh cadavers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(6):1743–1749.

7. Hamra ST. Frequent face lift sequelae. Hollow eyes and the lateral sweep: cause and repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(5):1658–1666.