Chapter 25 Endoscopic Endonasal Approach for Craniopharyngiomas

Craniopharyngiomas are benign tumors originating from squamous epithelial remnants of Rathke’s pouch, and can arise from any area from nasopharynx to the hypothalamus.1,2 Their consistency can be cystic, solid, or a combination of both; intralesional calcifications are a quite common finding (60% to 80% of cases). They are relatively infrequent, accounting for the 2% to 5% of all intracranial tumors, most frequently involving children (5–14 years) and older adults (50–74 years).3,4 These features contribute to a somewhat unpredictable biological behavior; therefore, the correct management strategy is controversial.5

Surgical management is challenging, especially when complete removal has been advocated as the most effective treatment.6–13 However, despite the benign nature of craniopharyngiomas, complete removal is not always possible due to their proximity and adhesions to vital neurovascular structures. Furthermore, craniopharyngiomas can recur even after radical resection and the surgical removal of recurrent craniopharyngiomas is even more complex due to the scarring and new adhesions.6–12,14,15

The surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas has been historically performed using various microscopic transcranial approaches, such as the subfrontal, frontolateral, and pterional routes. Trans-sphenoidal approaches, either microsurgical or endoscopic, have been restricted to intrasellar or intrasuprasellar subdiaphragmatic tumors.16,17 Nonetheless, in the last 20 years, the evolution of surgical techniques and technology have led to the progressive reduction of surgical invasiveness along with decreased morbidity. This has resulted in an increase of effectiveness for both transcranial and trans-sphenoidal approaches.18–25

The introduction and diffusion of the extended trans-sphenoidal approach, described by Weiss,26 created a new paradigm in trans-sphenoidal surgery opening a new corridor to the suprasellar space. This extended route for the removal of craniopharyngiomas was successfully adopted by Edward Laws.17,27

The widespread use of the endoscope in sinus surgery was introduced to trans-sphenoidal surgery for the treatment of pituitary tumors.28–30 The wider and panoramic view offered by the endoscope increased the versatility of the trans-sphenoidal approach and permitted its expansion to different parts of the skull base, thus allowing the removal of different “pure” supradiaphragmatic lesions.18,31–45

Furthermore, because craniopharyngiomas are infrachiasmatic midline tumors, the endonasal route provides the advantage of accessing the tumor without the need for brain or optic nerve retraction with a direct visualization through a linear surgical route.46,47

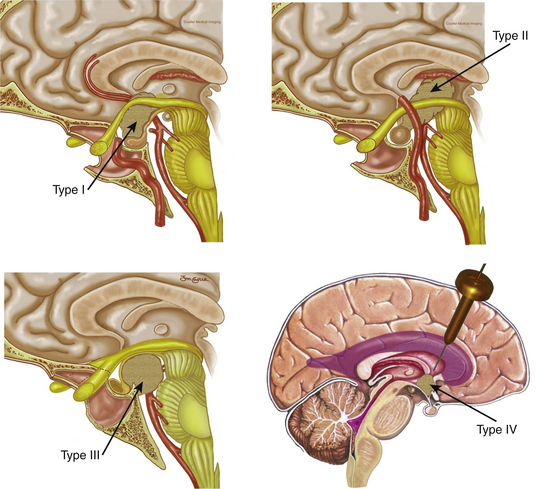

Since the approach has a caudal–cranial orientation, and the tumors are basically infrachiasmatic, the original classification of craniopharyngiomas in relation to the chiasm (pre or post fixed) is not practical. The infundibulum becomes the structure of reference; therefore, craniopharyngiomas have been recently classified accordingly43 as type 1, preinfundibular; type 2, transinfundibular; type 3, post- or retro-infundibular, further subdivision is based on rostral or caudal extension, whether it is to the anterior third ventricular (infundibular recess, hypothalamic) and interpeduncular fossa; and type 4, isolated third ventricular (not well accessed via endonasal routes) (Fig. 25-1). Consequently, specific surgical variations are required for each modality.43

Surgical Technique

Technical Nuances in Craniopharyngioma Surgery

The endoscopic endonasal approach involves the team of two surgeons, using three- or four-hand technique using the visualization provided by rod lens endoscope (18 cm in 4-mm length in diameter; Karl Storz Endoscopy-America, Inc., Culver City, CA) of varying lens angulations (0 degrees and 45 degrees). The surgical team is usually composed of an otolaryngologist and a neurosurgeon experienced in endoscopic endonasal surgery. The otolaryngologist performs the sinonasal approach and then drives the endoscope to provide a dynamic view of the surgical field throughout the procedure, while the neurosurgeon performs a bimanual dissection of the intradural structures.18

Exposure

We customarily initiate the procedure with removal of the inferior half of the right middle turbinate. Thereafter, the most posterior aspect of the posterior ethmoid sinuses is removed to expose the lamina papyracea bilaterally. A Hadad-Bassagasteguy (nasoseptal flap) is raised from the widest nasal cavity (usually the right in view of the middle turbinectomy) using a standard technique (see reconstruction section). At this point, the most posterior 2 cm of the nasal septum are removed and the left middle turbinate is displaced laterally (not resected). A wide sphenoidotomy is opened, enlarging the natural ostium until the lamina papyracea is in plane with the lateral wall of the orbit, the roof of the sphenoid sinus is in plane with that of the nose, and the bottom of the sinus is in full view. All intrasinus septae are removed and, if the sinus is not well pneumatized, the bone is drilled until all surgical landmarks are well exposed. These include the optic nerves and intracranial carotid artery (ICA) canals as well as lateral and medial opticocarotid recesses (MOCR and LOCR, respectively), and the clival recess.48,49 The LOCR lies at the junction of the optic nerve and ICA canals corresponding to the optic strut and the MOCR lies at the confluence of the optic canal and the paraclinoid carotid canal at the lateral portion of the tuberculum sellae. Image guidance is of assistance during these steps of the procedure. It should be remembered that continuous irrigation must be used to avoid thermal injury to the underlying optic nerve. Venous bleeding may be encountered in this region, which also represents the point of insertion of the SIS into the cavernous sinus. The bleeding can be controlled by packing microfibrillar collagen (Avitene, Ethicon, Inc.) or with the use of collagen (Surgifoam, Ethicon, Inc.) mixed with thrombin.

This opens an unobstructed corridor connecting the nasal cavities and the sphenoid sinus; thus, creating a single, large working cavity and bimanual access. The posterior ethmoidal arteries (PEA), encountered 4 to 7 mm anterior to the optic nerve and just anterior to the rostrum of the sphenoid, represent the anterior boundary of the exposure. Staying posterior to the PEAs prevents injury to the cribiform plate and the olfactory system associated with it. The surgical field extends from the posterior ethmoidal arteries rostrally to the clival recess caudally. Subsequently, the endoscope is kept in the patient’s right nostril, slightly stretching it superiorly, over the 12 o’clock position, to create space for the suction tip that is introduced at the 6 o’clock position.

Resection

Above all, it should be kept in mind that the concept of extracapsular dissection introduced by Laws17 takes precedence over any other consideration. One highlight of the endoscopic technique is that it approaches the tumor at its ventral aspect and all of the critical neurovascular structures will lie on its dorsum and perimeter. Furthermore, the endonasal endoscopic technique provides direct visualization of the inferior aspect of the chiasm, the infundibulum, the third ventricle, and/or the retro and parasellar spaces, which can be dissected free from tumor. Debulking of the solid and/or cystic component is performed followed by capsule mobilization and extracapsular sharp dissection. Debulking can be effectively performed using the two-suction technique43 or a combination of a suction and a cut-through instrument. It is important to mention that craniopharyngiomas are often adherent to the chiasm and/or hypothalamus, particularly in cases of recurrence.50 In these circumstances, we advise a partial resection in order to preserve critical neural tissue and its function.

In our experience, we have found that delicate “countertraction,” with a controlled suction fine tip (4 or 6 French), can be very useful to facilitate the isolation of the arachnoid bands and/or the attachments to other neurovascular structures, which then can be sharply dissected,43 as long there is no direct invasion.

Reconstruction

The reconstruction starts with a subdural inlay collagen matrix graft (Duragen, Integra LifeSciences). This graft contains the flow of CSF and facilitates the placement and healing of the graft. Immediately after the inlay reconstruction, the nasoseptal flap is rotated to cover the skull base defect. It is important that osseous surfaces in contact with the flap are stripped of mucosa, which would otherwise prevent adherence and healing of the flap to the defect.51,52 The flap is positioned to cover the defect overlapping its margins to allow contact with bone. In our experience this vascularized flap is superior to any other previously used technique. Its vascularity allows faster healing and an earlier, more resilient seal.

Surgical Considerations Based on Craniopharyngioma Type

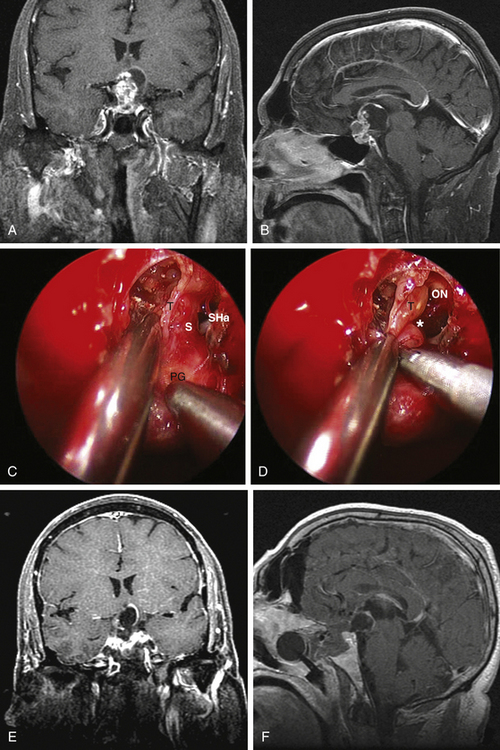

Type 1 craniopharyngiomas are preinfundibular and occupy the suprasellar cistern immediately anterior to the stalk. They tend to displace the chiasm superiorly and posteriorly. Concurrently, they displace the suprasellar arachnoid and the attached superior hypophyseal artery against the retrotubercular dura. These are the most accessible craniopharyngiomas via the endonasal route. Extreme care is critical during the dural opening to preserve the vascular supply for the optic nerves (SHa). Once the SHa are mobilized, the tumor can be debulked and this is followed by extracapsular sharp dissection as described above. SIS ligation and sellar exposure helps in defining the possibility of stalk preservation once the tumor is grossly removed (Fig. 25-2).

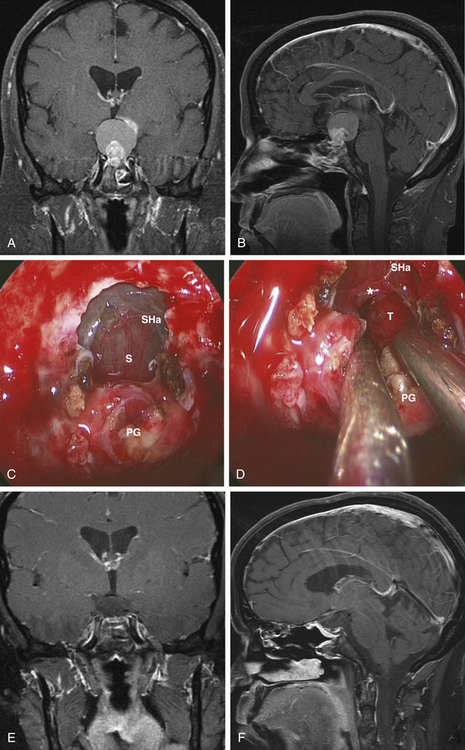

Type 2 craniopharyngiomas comprise those in the infundibular area. They grow from the inner aspect of the stalk and they tend to expand it circumferentially. In these cases, the stalk forms the capsule of the tumor. Once the SIS and sella are exposed, the anterior tumor capsule (distended stalk) is visualized. The SHa are dissected away and the capsule is entered. The center of the tumor is debulked and the capsule is dissected laterally and posteriorly. Unless there is a significant remaining stalk, the stalk/capsule should be sacrificed with a superior transection to avoid recurrence. This is the most difficult decision that has to be made in the operating room and becomes even more challenging when operating on children (Fig. 25-3).

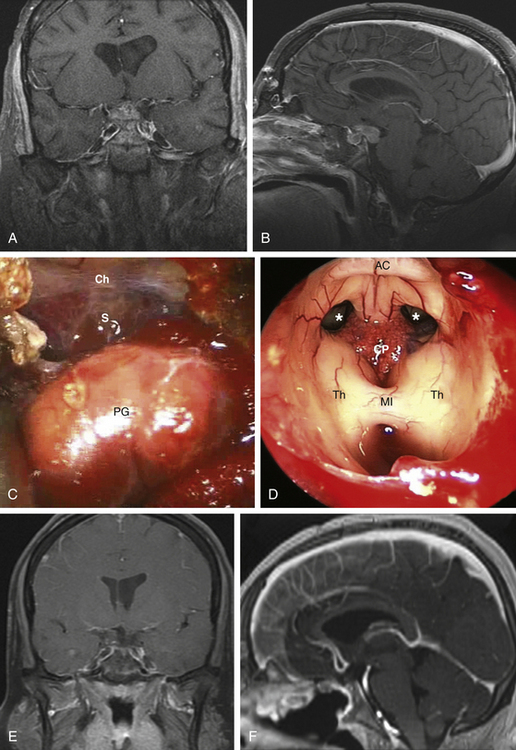

Type 3 craniopharyngiomas are those that are retroinfundibular. They are posterior to the pituitary stalk, which is confirmed once the SIS and pituitary aperture are transected. The suprasellar cistern is going to be relaxed and looks like there is no tumor present, which is all hidden behind the infundibulum. In these cases, we advocate a pituitary transposition followed by a superior clivectomy with removal of the dorsum sellae in order to have a direct access to the interpeduncular cistern.47 Once the transposition is done, a 45-degree endoscope is used to allow for a caudal–cranial orientation of dissection. The basilar artery is encountered initially with the Liliequist membrane. Craniopharyngiomas usually respect this membrane, displacing it downward. The tumor is debulked and the capsule is then dissected using microsurgical techniques with vascular proximal control on the basilar artery. The stalk is preserved anteriorly and the tumor is removed from its posterior surface. Often, the floor of the third ventricle is eroded by the tumor and this will allow a direct view at the end of the dissection (Fig. 25-4).

Discussion

Historically, transcranial microsurgical approaches have been advocated for the removal of craniopharyngiomas involving the suprasellar and ventricular areas. Trans-sphenoidal approach has been indicated for intrasuprasellar infradiaphragmatic lesions,16,17 extending upward out of an enlarged sella turcica and only with partial involvement of the anterior inferior aspect of the third ventricle, such as craniopharyngiomas of grades 1 and 2, according to the Samii’s classification.53 Furthermore, patients with normal pituitary function were often considered as a contraindication for endonasal route. These indications have been recently revised since the introduction of extended trans-sphenoidal approaches.54

The concept of accessing median lesions via median approaches holds inherent appeal and many others have reported a successful experience with the use of such a technique.26,32,36,40,45,55–59 Median approaches were boosted by the introduction of innovative tools such as the endoscope, high-definition cameras, and image guidance technology.

During the last decade multiple surgical centers around the world, already confident with the endoscopic endonasal management of pituitary tumors, began to perform “pure” extended endoscopic endonasal procedures for the removal of lesions involving different areas of the skull base.18,31–34,36–38,41,42 This technique actually provides a median and two-sided access and direct visualization of the suprasellar space without brain manipulation. This technique provides a wider, close-up view of the surgical field that permits the identification of surgical landmarks, thereby allowing the safe dissection and removal of the tumor without brain or optic apparatus retraction, even with a normal-sized sella. Besides, the risk of postoperative visual loss, which is strictly related to the integrity of the blood supply of the optic chiasm, seems to be reduced.

In 2004, Kassam and coworkers60 presented their initial experience with the treatment of craniopharyngiomas by mean of a fully endoscopic endonasal approach, describing an extension of the resection to the retrochiasmatic space and prepontine cisterns. Frank et al. in Bologna (Italy) reported a series of 10 patients with craniopharyngiomas who underwent a purely endoscopic endonasal approach.37 Six were purely suprasellar tumors without sellar enlargement. More recently, de Divitiis et al.46 confirmed the feasibility of this approach for the treatment of craniopharyngiomas, describing the use of an EEA for the removal of 10 cases of craniopharyngiomas. Seven were classified as suprasellar (6 had intraventricular extension and one purely intraventricular).

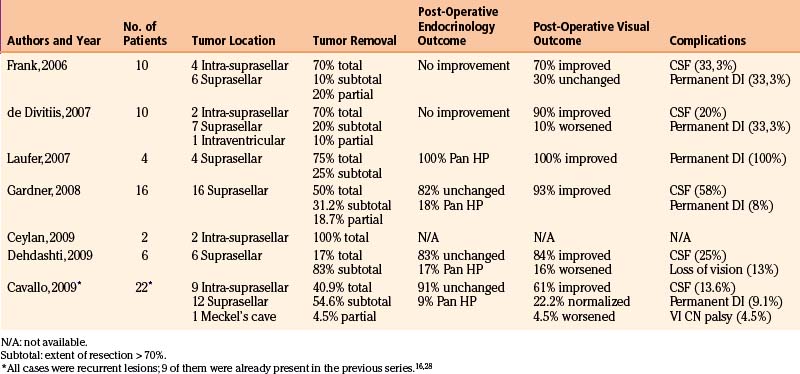

Following these encouraging results, others adopted EEA as a surgical strategy for the removal of various skull base lesions including craniopharyngiomas.46,50,61–64 The data from the main series of EEA for the removal of craniopharyngiomas is summarized in Table 25-1.

The analysis of data from these series, even though some included a small number of patients, confirmed the efficacy of the endoscopic endonasal technique for the treatment of craniopharyngiomas. In fact, it showed an overall gross-total/subtotal removal rate of 92.4% (residual tumor less then 25%) including a 60.4% of complete removal (no residual). These data seem to be at least equivalent to resection rates of the transcranial series6,7,10-12,16 reported in the literature, where they range from 0% to 60% with the exception of the study by Yasargil et al.12 (gross-total resection rate is of 90%). Notwithstanding the fact that the paramount aims of the surgery are the complete resection and cure at first attempt, we noted that with the direct subchiasmatic view offered by the endoscopic endonasal approach, there is no “blind” tumor dissection from hypothalamus, optic apparatus, and/or perforators resulting in a greater potential for preservation or even improvement of patient function, whether neurologic, ophthalmologic, or endocrinologic.

EEA has flourished thanks to the strict and systematic study of the anatomy of the skull base from the endoscopic perspective, the technological progress and the development and refinement of special instrumentation and the development of new approaches. Kassam et al. introduced the classification for craniopharyngiomas,43 providing further understanding of the anatomy pertaining to craniopharyngiomas. Indeed, understanding a tumor’s position relative to the stalk and other main vital surrounding structures is critical for the surgical management of craniopharyngiomas. Accordingly, we approached type 1 lesions usually via a transplanum approach,17,65 while for type 2 tumors, which generally extend intrasellar, SIS splitting40 allows full resection with a more rostral trajectory.

For type 3 tumors, where the infundibulum blocks the direct access, we found very useful to mobilize the pituitary gland and stalk to gain direct retrosellar and retroinfundibular access without the manipulation of neurovascular structures.47 Endoscope properties make safe removal of the posterior clinoid possible, which would be more difficult under a microscopic view. A skillful endoscopist is required to maintain the view in a narrow corridor while the clinoidectomy is performed. This latter maneuver is required to gain adequate access to retroinfundibular tumors, thus achieving a straight midline corridor to the interpeduncular cistern. It should be kept in mind that it is not always possible to determine the position of the infundibulum preoperatively and, above all, its relationships with the tumor, especially when dealing with large tumors. We learned that these relationships become clear after surgical exposure, so flaws in the preoperative planning can be accordingly modified.

Conversely, not all craniopharyngiomas are amenable to this kind of surgery, such as pure third ventricular tumors belonging to group 4.43 Eccentric extensions of the tumor into the middle cranial fossa, out of the range of surgical instruments, or those encasing or adherent to critical neurovascular structures (ICA, AcomA, optic apparatus, hypothalamus) are clinical scenarios where the effectiveness of the surgery will be limited regardless of the approach. A more limited access to the suprachiasmatic areas is provided whether the chiasm is prefixed or anteriorly displaced.18,33

As the approach developed, its surgical limitations, ability to control catastrophic bleeding in a narrow space31 and the higher risk of postoperative CSF leak36 were significant concerns. Nevertheless, advances in the exposure techniques and improvements in reconstruction using vascularized flaps51,66-68 have been developed and refined. These new strategies, combined with and the use of new haemostatic materials and customized instruments have significantly reduced such risks.52,69,70

Caldarelli M., di Rocco C., Papacci F., Colosimo C.Jr. Management of recurrent craniopharyngioma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140:447-454.

Cappabianca P., Cavallo L.M., Esposito F., De Divitiis E. Craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:1-3.

Cavallo L.M., Prevedello D.M., Solari D., et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach for residual or recurrent craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:578-589.

de Divitiis E., Cappabianca P., Cavallo L.M., et al. Extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for extrasellar craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:219-227. discussion 228

Fahlbusch R., Honegger J., Paulus W., et al. Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas: experience with 168 patients. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:237-250.

Fatemi N., Dusick J.R. de Paiva Neto MA, et al: Endonasal versus supraorbital keyhole removal of craniopharyngiomas and tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:269-284. discussion 284-286

Frank G., Pasquini E., Doglietto F., et al. The endoscopic extended transsphenoidal approach for craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(suppl 1):ONS75-ONS83.

Gardner P.A., Kassam A.B., Snyderman C.H., et al. Outcomes following endoscopic, expanded endonasal resection of suprasellar craniopharyngiomas: a case series. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:6-16.

Gardner P.A., Prevedello D.M., Kassam A.B., et al. The evolution of the endonasal approach for craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:1043-1047.

Haupt R., Magnani C., Pavanello M., et al. Epidemiological aspects of craniopharyngioma. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(suppl 1):289-293.

Honegger J., Buchfelder M., Fahlbusch R., et al. Transsphenoidal microsurgery for craniopharyngioma. Surg Neurol. 1992;37:189-196.

Jane J.A.Jr., Laws E.R. Craniopharyngioma. Pituitary. 2006;9:323-326.

Kassam A.B., Gardner P.A., Snyderman C.H., et al. Expanded endonasal approach, a fully endoscopic transnasal approach for the resection of midline suprasellar craniopharyngiomas: a new classification based on the infundibulum. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:715-728.

Kassam A.B., Prevedello D.M., Thomas A., et al. Endoscopic endonasal pituitary transposition for a transdorsum sellae approach to the interpeduncular cistern. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:57-72. discussion 72-74

Kassam A.B., Thomas A., Carrau R.L., et al. Endoscopic reconstruction of the cranial base using a pedicled nasoseptal flap. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:ONS44-52. ONS52-43:discussion 72-74

Laws E.R.Jr. Transsphenoidal microsurgery in the management of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 1980;52:661-666.

Laws E.R.Jr. Transsphenoidal removal of craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21(suppl 1):57-63.

Maira G., Anile C., Albanese A., et al. The role of transsphenoidal surgery in the treatment of craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:445-451.

Minamida Y., Mikami T., Hashi K., Houkin K. Surgical management of the recurrence and regrowth of craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:224-232.

Prevedello D.M., Doglietto F., Jane J.A.Jr., et al. History of endoscopic skull base surgery: its evolution and current reality. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:206-213.

Samii M., Samii A.. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas, Schmidek H.H., editor, Schmidek and Sweet Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods and Results, Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2000;vol 1:489-502.

Symon L., Sprich W. Radical excision of craniopharyngioma. Results in 20 patients. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:174-181.

Van Effenterre R., Boch A.L. Craniopharyngioma in adults and children: a study of 122 surgical cases. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:3-11.

Wisoff J.H. Surgical management of recurrent craniopharyngiomas. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21(suppl 1):108-113.

Yasargil M.G., Curcic M., Kis M., et al. Total removal of craniopharyngiomas. Approaches and long-term results in 144 patients. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:3-11.

1. Jane J.A.Jr, Laws E.R. Craniopharyngioma. Pituitary. 2006;9:323-326.

2. Lewin R., Ruffolo E., Saraceno C. Craniopharyngioma arising in the pharyngeal hypophysis. South Med J. 1984;77:1519-1523.

3. Bunin G.R., Surawicz T.S., Witman P.A., et al. The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:547-551.

4. Haupt R., Magnani C., Pavanello M., et al. Epidemiological aspects of craniopharyngioma. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(suppl 1):289-293.

5. Cappabianca P., Cavallo L.M., Esposito F., De Divitiis E. Craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:1-3.

6. Fahlbusch R., Honegger J., Paulus W., et al. Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas: experience with 168 patients. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:237-250.

7. Hoffman H.J. Surgical management of craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21(suppl 1):44-49.

8. Minamida Y., Mikami T., Hashi K., Houkin K. Surgical management of the recurrence and regrowth of craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:224-232.

9. Samii M., Bini W. Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas. Zentralbl Neurochir. 1991;52:17-23.

10. Symon L., Sprich W. Radical excision of craniopharyngioma. Results in 20 patients. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:174-181.

11. Van Effenterre R., Boch A.L. Craniopharyngioma in adults and children: a study of 122 surgical cases. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:3-11.

12. Yasargil M.G., Curcic M., Kis M., et al. Total removal of craniopharyngiomas. Approaches and long-term results in 144 patients. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:3-11.

13. Zuccaro G. Radical resection of craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:679-690.

14. Caldarelli M., di Rocco C., Papacci F., Colosimo C.Jr. Management of recurrent craniopharyngioma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140:447-454.

15. Wisoff J.H. Surgical management of recurrent craniopharyngiomas. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21(suppl 1):108-113.

16. Honegger J., Buchfelder M., Fahlbusch R., et al. Transsphenoidal microsurgery for craniopharyngioma. Surg Neurol. 1992;37:189-196.

17. Laws E.R.Jr. Transsphenoidal microsurgery in the management of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 1980;52:661-666.

18. de Divitiis E., Cavallo L.M., Cappabianca P., Esposito F. Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach for the removal of suprasellar tumors: Part 2. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:46-58. discussion 58-59

19. Delashaw J.B.Jr, Tedeschi H., Rhoton A.L. Modified supraorbital craniotomy: technical note. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:954-956.

20. Fahlbusch R., Schott W. Pterional surgery of meningiomas of the tuberculum sellae and planum sphenoidale: surgical results with special consideration of ophthalmological and endocrinological outcomes. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:235-243.

21. Fatemi N., Dusick J.R. de Paiva Neto MA, et al. Endonasal versus supraorbital keyhole removal of craniopharyngiomas and tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:269-284. discussion 284-286

22. Goel A., Muzumdar D., Desai K.I. Tuberculum sellae meningioma: a report on management on the basis of a surgical experience with 70 patients. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1358-1363. discussion 1363-1364

23. Jallo G.I., Benjamin V. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: microsurgical anatomy and surgical technique. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1432-1439. discussion 1439-1440

24. Jarrahy R., Cha S.T., Berci G., Shahinian H.K. Endoscopic transglabellar approach to the anterior fossa and paranasal sinuses. J Craniofac Surg. 2000;11:412-417.

25. Reisch R., Perneczky A. Ten-year experience with the supraorbital subfrontal approach through an eyebrow skin incision. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:242-255.

26. Weiss M.H. The transnasal transsphenoidal approach. In: Apuzzo M.L.J., editor. Surgery of the third ventricle. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1987:476-494.

27. Laws E.R.Jr. Transsphenoidal removal of craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21(suppl 1):57-63.

28. Cappabianca P., Alfieri A., de Divitiis E. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach to the sella: towards functional endoscopic pituitary surgery (FEPS). Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 1998;41:66-73.

29. Cappabianca P., Cavallo L.M., de Divitiis E. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:933-940. discussion 940-941

30. Carrau R.L., Jho H.D., Ko Y. Transnasal-transsphenoidal endoscopic surgery of the pituitary gland. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:914-918.

31. Cappabianca P., Cavallo L.M., Esposito F., et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal approach to the midline skull base: the evolving role of transsphenoidal surgery. In: Pickard J.D., Akalan N., Di Rocco C. Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery. Wien New York: Springer; 2008:52-199.

32. Cappabianca P., Frank G., Pasquini E., et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approaches to the suprasellar region, planum sphenoidale and clivus. In: de Divitiis E., Cappabianca P. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery. Wien – New York: Springer; 2003:176-187.

33. Cavallo L.M., de Divitiis O., Aydin S., et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach to the suprasellar area: anatomic considerations—part 1. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:ONS-24-ONS-34.

34. Cavallo L.M., Messina A., Cappabianca P., et al. Endoscopic endonasal surgery of the midline skull base: anatomical study and clinical considerations. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19:E2.

35. Couldwell W.T., Weiss M.H., Rabb C., et al. Variations on the standard transsphenoidal approach to the sellar region, with emphasis on the extended approaches and parasellar approaches: surgical experience in 105 cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:539-550.

36. Dusick J.R., Esposito F., Kelly D.F., et al. The extended direct endonasal transsphenoidal approach for nonadenomatous suprasellar tumors. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:832-841.

37. Frank G., Pasquini E., Doglietto F., et al. The endoscopic extended transsphenoidal approach for craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(suppl 1):ONS75-ONS83.

38. Frank G., Pasquini E., Mazzatenta D. Extended transsphenoidal approach. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:917-918.

39. Jho H.D. The expanding role of endoscopy in skull-base surgery. Indications and instruments. Clin Neurosurg. 2001;48:287-305.

40. Kaptain G.J., Vincent D.A., Sheehan J.P., Laws E.R.Jr. Transsphenoidal approaches for the extracapsular resection of midline suprasellar and anterior cranial base lesions. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:94-101.

41. Kassam A., Snyderman C.H., Mintz A., et al. Expanded endonasal approach: the rostrocaudal axis. Part I. Crista galli to the sella turcica. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19:E3.

42. Kassam A., Snyderman C.H., Mintz A., et al. Expanded endonasal approach: the rostrocaudal axis. Part II. Posterior clinoids to the foramen magnum. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19:E4.

43. Kassam A.B., Gardner P.A., Snyderman C.H., et al. Expanded endonasal approach, a fully endoscopic transnasal approach for the resection of midline suprasellar craniopharyngiomas: a new classification based on the infundibulum. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:715-728.

44. Kato T., Sawamura Y., Abe H., Nagashima M. Transsphenoidal-transtuberculum sellae approach for supradiaphragmatic tumours: technical note. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140:715-719.

45. Kouri J.G., Chen M.Y., Watson J.C., Oldfield E.H. Resection of suprasellar tumors by using a modified transsphenoidal approach. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:1028-1035.

46. de Divitiis E., Cappabianca P., Cavallo L.M., et al. Extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for extrasellar craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:219-227. discussion 228

47. Kassam A.B., Prevedello D.M., Thomas A., et al. Endoscopic endonasal pituitary transposition for a transdorsum sellae approach to the interpeduncular cistern. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:57-72. discussion 72-74

48. Clemente C.D. Gray’s Anatomy of the Human Body, 30th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1985.

49. Rhoton A.L.Jr. The supratentorial cranial space: microsurgical anatomy and surgical approaches. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:S1-385.

50. Cavallo L.M., Prevedello D.M., Solari D., et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach for residual or recurrent craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:578-589.

51. Hadad G., Bassagasteguy L., Carrau R.L., et al. A novel reconstructive technique after endoscopic expanded endonasal approaches: vascular pedicle nasoseptal flap. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1882-1886.

52. Kassam A.B., Thomas A., Carrau R.L., et al. Endoscopic reconstruction of the cranial base using a pedicled nasoseptal flap. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:ONS44-ONS52. discussion ONS52–53

53. Samii M., Samii A.. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas, Schmidek H.H., editor, Schmidek and Sweet Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods and Results, Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2000;vol 1:489-502.

54. Prevedello D.M., Doglietto F., Jane J.A.Jr, et al. History of endoscopic skull base surgery: its evolution and current reality. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:206-213.

55. Dumont A.S., Kanter A.S., Jane J.A.Jr, Laws E.R.Jr. Extended transsphenoidal approach. Front Horm Res. 2006;34:29-45.

56. Gardner P.A., Prevedello D.M., Kassam A.B., et al. The evolution of the endonasal approach for craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:1043-1047.

57. Kim J., Choe I., Bak K., et al. Transsphenoidal supradiaphragmatic intradural approach: technical note. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2000;43:33-37.

58. Maira G., Anile C., Albanese A., et al. The role of transsphenoidal surgery in the treatment of craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:445-451.

59. Mason R.B., Nieman L.K., Doppman J.L., Oldfield E.H. Selective excision of adenomas originating in or extending into the pituitary stalk with preservation of pituitary function. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:343-351.

60. Kassam A. Fully endoscopic endonasal resection of parasellar craniophryngiomas: an early experience amd review of litherature. Skull Base. 12(suppl 1), 2004. (abstract)

61. Ceylan S., Koc K., Anik I. Extended endoscopic approaches for midline skull-base lesions. Neurosurg Rev. 2009;32:309-319. discussion 318-319

62. Dehdashti A.R., Ganna A., Witterick I., Gentili F. Expanded endoscopic endonasal approach for anterior cranial base and suprasellar lesions: indications and limitations. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:677-687. discussion 687-689

63. Gardner P.A., Kassam A.B., Snyderman C.H., et al. Outcomes following endoscopic, expanded endonasal resection of suprasellar craniopharyngiomas: a case series. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:6-16.

64. Laufer I., Anand V.K., Schwartz T.H. Endoscopic, endonasal extended transsphenoidal, transplanum transtuberculum approach for resection of suprasellar lesions. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:400-406.

65. Hardy J., Lalonde J.L. [Removal by trans-sphenoidal route of a giant craniopharyngioma.] Union Med Can. 1963;92:1124-1129.

66. Fortes F.S., Carrau R.L., Snyderman C.H., et al. The posterior pedicle inferior turbinate flap: a new vascularized flap for skull base reconstruction. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1329-1332.

67. Oliver C.L., Hackman T.G., Carrau R.L., et al. Palatal flap modifications allow pedicled reconstruction of the skull base. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:2102-2106.

68. Zanation A.M., Snyderman C.H., Carrau R.L., et al. Minimally invasive endoscopic pericranial flap: a new method for endonasal skull base reconstruction. Laryngoscope. 2008;119:13-18.

69. Cavallo L.M., Messina A., Esposito F., et al. Skull base reconstruction in the extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for suprasellar lesions. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:713-720.

70. Pinheiro-Neto C.D., Prevedello D.M., Carrau R.L., et al. Improving the design of the pedicled nasoseptal flap for skull base reconstruction: a radioanatomic study. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1560-1569.