Chapter 13

Endomyocardial Biopsy

1. Why is an endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) performed?

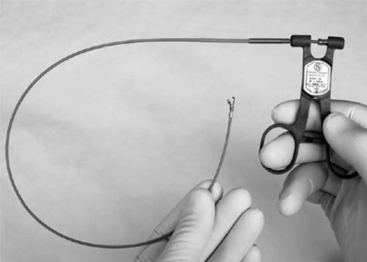

A bioptome is shown in Figure 13-1. The Stanford-Caves-Schultz and the King bioptomes access the right ventricle through the right internal jugular vein. A modified Cordis bioptome (B-18110, Wolfgang Meiners Medizintechnik, Monheim, Germany) has been used for access from the right femoral vein. The subclavian and left femoral veins are used less frequently.

The femoral artery may be used as a percutaneous access site for left ventricular biopsy.

3. What are the risks associated with an EMB?

Risks correlated with EMB are summarized in Table 13-1. EMB is associated with a serious acute complication rate of less than 1% using the current flexible bioptomes, and the overall rate of complication is reported as less than 6% in most case series. Complications include access-site hematoma, transient right bundle branch block (RBBB), transient arrhythmias, tricuspid regurgitation, and, rarely, pulmonary embolism. Life-threatening complications occur far less frequently. Right ventricular perforation was reported in less than 1% of patients. Following cardiac transplant, the risk is especially low. The risks of EMB depend on the clinical state of the patient, the experience of the operator, and site procedural volume.

TABLE 13-1

ADVERSE EVENTS WHICH CAN OCCUR WITH ENDOMYOCARDIAL BIOPSY

IVCD, Intraventricular conduction delay; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

4. How is the EMB tissue analyzed?

Specimen preparation depends on the clinical question to be answered.

5. When should EMB be performed?

EMB is not commonly indicated in the evaluation of heart disease and should only be performed in specific clinical circumstances in which EMB results may meaningfully modify prognosis or guide treatment. In 2007, an American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and European Society of Cardiology (AHA/ACC/ESC) scientific statement recommended that EMB be used selectively in a limited set of clinical scenarios described in the answers to Questions 6 through 8. Since that statement, reports suggest that EMB may also have a role in the evaluation of idiopathic heart block for possible cardiac sarcoidosis or giant cell myocarditis.

6. What are the class I recommendations to perform an EMB?

Clinical scenario 1: Unexplained new-onset heart failure (HF) of less than 2 weeks duration associated with a normal size or dilated cardiomyopathy in addition to hemodynamic compromise

Clinical scenario 1: Unexplained new-onset heart failure (HF) of less than 2 weeks duration associated with a normal size or dilated cardiomyopathy in addition to hemodynamic compromise

Clinical scenario 2: Unexplained new-onset HF of 2 weeks to 3 months duration associated with a dilated left ventricle and new ventricular arrhythmias, Mobitz type II second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, third-degree AV block, or failure to respond to usual care within 1 to 2 weeks

Clinical scenario 2: Unexplained new-onset HF of 2 weeks to 3 months duration associated with a dilated left ventricle and new ventricular arrhythmias, Mobitz type II second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, third-degree AV block, or failure to respond to usual care within 1 to 2 weeks

7. When is it reasonable to perform an EMB (class IIa recommendation)?

Clinical scenario 3: Unexplained HF of more than 3 months duration associated with a dilated left ventricle and new ventricular arrhythmias, Mobitz type II second-degree AV block, third-degree AV block, or failure to respond to usual care within 1 to 2 weeks

Clinical scenario 3: Unexplained HF of more than 3 months duration associated with a dilated left ventricle and new ventricular arrhythmias, Mobitz type II second-degree AV block, third-degree AV block, or failure to respond to usual care within 1 to 2 weeks

Clinical Scenario 4: Unexplained HF with a dilated cardiomyopathy of any duration associated with a suspected allergic reaction in addition to eosinophilia

Clinical Scenario 4: Unexplained HF with a dilated cardiomyopathy of any duration associated with a suspected allergic reaction in addition to eosinophilia

Clinical Scenario 5: Unexplained HF associated with suspected anthracycline cardiomyopathy

Clinical Scenario 5: Unexplained HF associated with suspected anthracycline cardiomyopathy

Clinical Scenario 6: HF associated with restrictive cardiomyopathy

Clinical Scenario 6: HF associated with restrictive cardiomyopathy

Clinical Scenario 7: Suspected cardiac tumors, with the exception of typical myxomas

Clinical Scenario 7: Suspected cardiac tumors, with the exception of typical myxomas

Clinical Scenario 8: Unexplained cardiomyopathy in children

Clinical Scenario 8: Unexplained cardiomyopathy in children

Clinical Scenario 9: Unexplained new-onset HF of 2 weeks to 3 months duration associated with a dilated cardiomyopathy without new ventricular arrhythmias or AV block

Clinical Scenario 9: Unexplained new-onset HF of 2 weeks to 3 months duration associated with a dilated cardiomyopathy without new ventricular arrhythmias or AV block

Clinical scenario 10: Unexplained HF of more than 3 months duration associated with a dilated cardiomyopathy without new ventricular arrhythmias or AV block that responds to usual care within 1 to 2 weeks

Clinical scenario 10: Unexplained HF of more than 3 months duration associated with a dilated cardiomyopathy without new ventricular arrhythmias or AV block that responds to usual care within 1 to 2 weeks

8. When can you consider EMB (class IIb recommendation)?

Clinical Scenario 11: HF associated with unexplained hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Clinical Scenario 11: HF associated with unexplained hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Clinical Scenario 12: Suspected arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

Clinical Scenario 12: Suspected arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

9. What are some of the findings on pathology in different cardiac conditions?

Lymphocytic myocarditis: diagnosis of myocarditis is made when there is inflammatory infiltrate with associated myocyte damage

Lymphocytic myocarditis: diagnosis of myocarditis is made when there is inflammatory infiltrate with associated myocyte damage

Idiopathic giant cell myocarditis: myocyte necrosis, poorly formed granulomas and eosinophils

Idiopathic giant cell myocarditis: myocyte necrosis, poorly formed granulomas and eosinophils

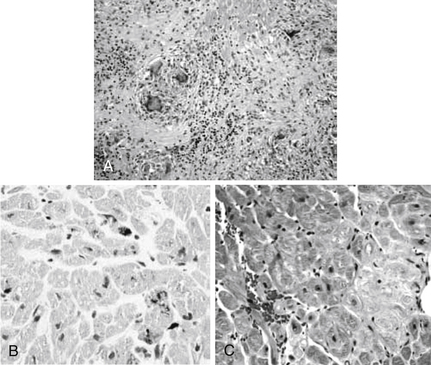

Sarcoidosis: well-formed nonnecrotizing granulomas (Fig. 13-2, A)

Sarcoidosis: well-formed nonnecrotizing granulomas (Fig. 13-2, A)

Figure 13-2 Examples of endomyocardial biopsies (EMBs). A, EMB of sarcoidosis showing noncaseating granulomas. B, EMB of hemochromatosis showing iron deposition in the myocytes. C, EMB of amyloid showing pericellular deposition of amyloid. (From Narula N, Narula J, Dec GW: Endomyocardial biopsy for non-transplant related disorders. Am J Clin Pathol 123(suppl):S106-S118, 2005.)

Dilated cardiomyopathy: commonly associated with end-stage hypertensive, ischemic, valvular disease. The most common finding in dilated cardiomyopathy is myocyte hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis.

Dilated cardiomyopathy: commonly associated with end-stage hypertensive, ischemic, valvular disease. The most common finding in dilated cardiomyopathy is myocyte hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis.

Hemochromatosis: iron is demonstrated (Fig. 13-2, B)

Hemochromatosis: iron is demonstrated (Fig. 13-2, B)

Amyloidosis: a Congo red stain shows apple-green birefringence under polarized light (Fig. 13-2, C)

Amyloidosis: a Congo red stain shows apple-green birefringence under polarized light (Fig. 13-2, C)