CHAPTER 33 Endometriosis

Introduction

Endometriosis is one of the most common benign gynaecological conditions. It is second only to uterine fibroids as the most common reason for major surgical procedures in women under 45 years of age. It has been estimated that it is present in between 10% and 25% of women presenting with gynaecological symptoms in the UK and USA (Tyson 1974). These figures are based on the findings of patients who have undergone laparoscopy for diagnostic indications, such as pelvic pain or infertility, or in patients undergoing laparotomy. Although it is such a widespread condition, it is true to say that there is limited understanding regarding its aetiology and pathogenesis, and the condition still arouses much controversy with regard to its diagnosis, treatment and management. Endometriosis varies in severity from minimal disease with a few peritoneal implants to severe disease producing adhesions, deep infiltrating lesions and involvement with ovarian cyst formation.

Prevalence

No racial differences in the incidence of the disease have been found, except for Japanese women who have been reported to have twice the incidence of Caucasian women (Miyazawa 1976).

The exact prevalence of endometriosis is unknown since precise diagnosis depends on observation of implants, predominantly at the time of laparoscopy or laparotomy. Until simple non-invasive screening tests are developed, the true prevalence will remain unknown. Current prevalence therefore depends upon identification in women who are either symptomatic or undergoing various operative procedures. The incidence is markedly variable as the data in Table 33.1 show, but the prevalence of endometriosis in the reproductive years is estimated to be approximately 10% (Eskenazi and Warner 1997). Endometriosis commonly affects women during their childbearing years. In the main, this is reflected in deleterious sexual, reproductive and social consequences as a result of its associated painful symptoms and often associated infertility. Symptomatology may extend over several decades of a patient’s life because of its often late diagnosis and the recurrent nature of the disease. For individual patients and healthcare systems, it represents a major call upon resource use.

Table 33.1 Prevalence of endometriosis through various presentations

| Presentation | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Unexplained infertility | 70–80* |

| Infertile women (all causes) | 15–20* |

| At diagnostic laparoscopy | 0–53† |

| At treatment laparoscopy | 0.1–50† |

| Women undergoing sterilization | 2‡ |

| In women with diagnosed first-degree relatives | 7§ |

* Source: Kistner RW 1977 In: Sciarra J (ed) Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Vol. 1. Harper and Row, London.

† Source: Houston DE 1984 Epidemiology Reviews 6: 167–191.

‡ Source: Strathy JH, Molgaard GA, Coulam CB, Molton LJ III 1982 Fertility and Sterility 38: 667–672.

§ Source: Simpson JL, Elias S, Malinak LR, Buttram VC Jr 1980 American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 137: 327–331.

Pathogenesis

Transformation of coelomic epithelium

This theory, first described by Meyer (1919), postulated the possibility of differentiation by metaplasia towards an endometrial-like tissue of the original coelomic membrane following prolonged irritation and oestrogen stimulation. It is proposed that these adult cells undergo dedifferentiation back to their primitive origin and then transform to endometrial cells. If this theory is correct, metaplasia should occur wherever coelomic membranes are present. This theory has many attractions which could explain the occurrence of endometriosis in nearly all the ectopic sites in the presence of aberrant Müllerian cells. What induces this transformation — whether it is hormonal stimuli, inflammatory irritation or other processes — is uncertain. If coelomic metaplasia is similar to metaplasia elsewhere, the frequency of the disorder should increase with advancing age. The clinical pattern of endometriosis is distinctly different from this, with an abrupt halt in the disease with the cessation of menses at the menopause and reduced oestrogen production, thus raising some questions over this theory.

Menstrual regurgitation and implantation (metastatic theory)

As early as 1927, Sampson proposed the metastatic theory, postulating that retrograde menstrual flow transported desquamated endometrial fragments through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity (Sampson 1927). Once there, the still viable cells subsequently implanted and began growth and invasion. In support of this theory, experimental endometriosis has been induced in animals with replacement of menstrual fluid or endometrial tissue in the peritoneal cavity. Supporting this theory in humans is the finding that endometriosis is commonly found in young girls with associated abnormalities in the genital tract causing obstruction to the outflow of menstrual fluid (Schifrin et al 1973). Halme et al (1984) observed bloody fluid at the time of menstruation in the pelvis during laparoscopic assessment, but as this finding occurs in up to 90% of all women, it is regarded as a physiological phenomenon. The high incidence of retrograde menstruation suggests that this phenomenon alone does not give rise to endometriosis, but that some other factor(s) must be involved in development of the disease. These factors could include some alteration in the (uterine) endometrium, altered immune response to retrograde menstruation (hence failure to clear the peritoneal cavity of debris efficiently), or a more favourable peritoneal environment which may stimulate the growth and implantation of ectopic endometrium within the peritoneal cavity itself.

Genetic and immunological factors

Many studies have indicated that there may be a genetic factor related to endometriosis since the disease is more prevalent in certain families. It has been shown that women with an affected first-degree relative have a seven times higher risk of developing endometriosis, which may be severe (Simpson et al 1980, Halme et al 1986). Endometriosis is also more common in monozygotic twin sisters than dizygotic twins, but no association was found with specifically identified tissue types (Simpson et al 1984). Whilst Dmowski et al (1981) demonstrated a decreased cellular immunity to endometriotic tissue in women with endometriosis, no clinically significant immune system abnormality has been observed in women with the disease; hence, the precise genetic or immune components increasing an individual’s potential to develop this disorder are yet to be defined.

Endometrial disease theory

Many view the superficial implants as ‘physiological’ lesions which may regress spontaneously. Deep infiltrating lesions and ovarian endometriotic cysts are pathological and arise from cells that have undergone somatic mutations. Such mutations may have been produced by environmental factors (e.g. pollutants, dioxins). These abnormal cells then develop into a ‘benign tumour’ consisting of endometriotic glands and stroma. For a review on environmental factors in the aetiology of endometriosis, the reader is directed to Missmer and Mohllagee (2008).

Further support of the above theory stems from biochemical differences demonstrated in the endometrium in patients with and without endometriosis (Guidice and Kao 2004). These include differences in the expression of metalloproteinases, tumour susceptibility genes and angiogenic factors. Such changes may allow certain types of retrograde endometrial fragments to implant more readily than others, and this may be due to an underlying inherited genetic tendency.

Conclusion

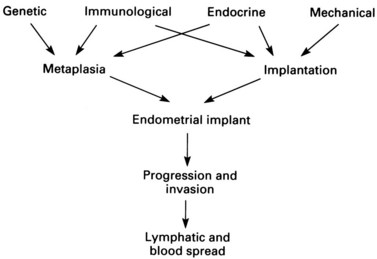

The conclusion reached from the above theories is that pelvic endometriosis is probably a consequence of transplantation of viable endometrial cells regurgitated at the time of menstruation from the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity. In addition, transport of endometrial cells may occur by other routes (some iatrogenic). It is unclear whether endometriotic implants are derived from in-situ pluripotential cells generated by metastatic seeding, but it is known that endocrine and immunological factors allow growth and spread within the pelvis and neighbouring organs. Delayed childbearing, either by choice or infertility, has been implicated as a risk factor for the development of endometriosis. The risk of developing endometriosis also corresponds with cumulative menstruation, menstrual frequency and volume. Women with shorter menstrual cycles of less than 27 days and longer flows (more than 7 days) are twice as likely to develop the disease compared with women with longer cycles and shorter flows. Thus, many components are necessary to allow endometriotic deposits to implant and subsequently grow (Figure 33.1).

Peritoneal Fluid Environment in Endometriosis

Peritoneal macrophages

Normal peritoneal fluid contains approximately 106 cells per ml; 90% are macrophages, and the remainder are lymphocytes and desquamated mesothelial cells. The role of peritoneal macrophages in women with endometriosis has been the source of much interest, and women with endometriosis associated with infertility have been reported to have significantly higher concentrations of macrophages in peritoneal fluid than either fertile women or infertile women without endometriosis. Macrophages in patients with endometriosis appeared to be highly phagocytic against spermatozoa in vitro compared with those from fertile women or infertile women without endometriosis (Muscato et al 1982). In addition, they are also able to survive better in vitro than those from fertile controls (Halme et al 1986). Peritoneal fluid from patients with endometriosis has also been shown to have a cytotoxic effect on in-vivo cleavage of mouse embryos. These findings on the quantitative and qualitative properties of macrophages in peritoneal fluid may partially explain the mechanisms of infertility in patients with endometriosis.

Prostaglandins and prostanoids

The role of prostaglandins and their metabolites in peritoneal fluid in the pathogenesis and symptomatology of endometriosis is controversial. It has been reported that increased levels of prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) are found in the peritoneal fluid of patients with the disease (Meldrum et al 1977). In addition, increased peritoneal fluid volume and increased concentrations of the prostaglandin metabolites thromboxane B2 and 6-keto PGF2α have been noted. Other investigators have found no increase in either the volume of peritoneal fluid or its concentrations of prostaglandins or metabolites (Rock et al 1982). These conflicting reports may reflect the timing of peritoneal fluid sampling and difficulties in assay measurement of the small quantities of substrates, all of which have very short half-lives.

Presentation

Atypical bleeding patterns are a leading symptom in a variety of gynaecological diseases, but may also characterize patients with endometriosis. Premenstrual spotting and menometrorrhagia are frequently noted. On the other hand, cyclical rectal bleeding or haematuria is pathognomonic of the disease and, although rarely observed (1–2% of cases), these symptoms give strong evidence for bowel or bladder involvement. Painful micturition or defaecation at the time of menstruation may be the first signs of progressing disease. The various symptoms of endometriosis as found in various sites of implantation are shown in Table 33.2.

Table 33.2 Symptoms of endometriosis related to sites of implants

| Symptoms | Site |

|---|---|

| Dysmenorrhoea | Reproductive organs |

| Lower abdominal pain | |

| Pelvic pain | |

| Low back pain | |

| Menstrual irregularity | |

| Rupture/torsion endometrioma | |

| Infertility | |

| Cyclical rectal bleeding | Gastrointestinal tract |

| Tenesmus | |

| Diarrhoea/cyclic constipation | |

| Cyclical haematuria | Urinary tract |

| Dysuria (cyclical) | |

| Ureteric obstruction | |

| Cyclical haemoptysis | Lungs |

| Cyclical pain and bleeding | Surgical scars/umbilicus |

| Cyclical pain and swelling | Limbs |

Correlation of symptoms and severity of endometriosis

The frequencies of the more common symptoms in endometriosis patients are summarized in Table 33.3. Whilst the symptoms of dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia and pelvic pain can occur with other gynaecological disorders, it is the combination, cyclical and menstrually related component of several symptoms which should alert the clinician to the potential underlying presence of endometriosis. Many women have delayed diagnosis of their condition, which may mean that it has progressed to a more extensive and potentially less reversible or curable stage at the time of diagnosis.

Table 33.3 Frequency of the more common symptoms in endometriosis patients

| Symptom | Likely frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Dysmenorrhoea | 60–80 |

| Pelvic pain | 30–50 |

| Infertility | 30–40 |

| Dyspareunia | 25–40 |

| Menstrual irregularities | 10–20 |

| Cyclical dysuria/haematuria | 1–2 |

| Dyschezia | 1–2 |

| Rectal bleeding (cyclic) | <1 |

There appears to be little correlation between sites involved in endometriosis and symptoms. Various ‘types’ of symptoms can, however, be related to some degree to the system involved (see Table 33.2). However, these do not always correlate with the anatomy and type of pain innervation of the pelvis (for review, see MacLaverty and Shaw 1995).

Deeply infiltrating endometriosis is very strongly associated with the presence and severity of pelvic pain. In addition, superficial non-pigmented endometriosis has the capacity to produce more prostaglandin F (PGF) than pigmented classic powder burn lesions. PGF is implicated in pain causation (Vernon et al 1986). Thus, in the early, less florid stages before it has become destructive and more easily recognized, endometriosis may be producing large quantities of PGF and hence possesses greater potential to increase the severity of pain. The type of pain may alter with disease progression, with constant pain and exacerbation at the menses initially in the disease, and pain later becoming continuous due to scar formation and organ fixity.

Endometriosis and Infertility

Endometriosis was one of the most frequently made diagnoses in couples undergoing infertility investigation, when routine use of laparoscopy for investigation of such couples was employed, in past years. The assumption was made that endometriotic implants are responsible for the patient’s inability to conceive. Estimates of the incidence of endometriosis in the general population of reproductive age vary between 2% and 10%. From retrospective studies in infertile patients, the incidence has been reported as being between 20% and 40% (Mahmood and Templeton 1990). This increased incidence in infertile patients has led many clinicians to consider the endometriotic implants to be responsible, in some way, for the associated infertility. The question is how, and a number of suggested mechanisms have been reported. These are summarized in Table 33.4. For the majority of these potential causes, there are few or no consistent data to provide a sustainable explanation. Thus, the nature of the relationship between mild endometriosis and infertility remains unresolved.

Table 33.4 Possible mechanisms of causation of infertility with mild endometriosis

| Problem area | Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Ovarian function |

Although there may be some debate about the role of filmy peritubal or periovarian adhesions in infertility, it is accepted that with increasing severity of endometriosis, adhesions become more common and the chances of a natural conception decrease. The majority of specialists would divide such adhesions if found at laparoscopy and if appropriate consent had been obtained, although laparoscopy is no longer routinely undertaken in asymptomatic infertile women. Evidence that the treatment of endometriosis benefits fertility would provide proof that endometriosis is linked with infertility. Historically, many studies have utilized ovarian-suppression treatments with progestogens, danazol and/or gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues in the hope of treating endometriosis and enhancing fertility. The majority of these patients had minimal or mild endometriosis (see later for classification). These studies show that 3–6 months of medication prevents fertility during treatment, but does not increase pregnancy rates following treatment cessation. Meta-analysis showed no difference in pregnancy rate between ovarian suppression and no treatment (relative risk 0.98; confidence interval 0.81–1.15) (Hughes et al 1993, Adamson and Pasta 1994). There was no difference among different ovarian-suppression agents, and the current recommendation is that ovarian suppression in the infertile patient is not justified because of lack of effectiveness on improving conception rates over a conservative approach alone.

Laparoscopic surgical destruction, excision or laser ablation of endometriotic deposits has become popular in recent years and is helpful in pain management of selective endometriosis patients (see later). However, its role in patients with endometriosis and infertility without tubo-ovarian adhesion, endometriomas or other pathology is in question. The ENDOCAN randomized trial from Canada showed a higher pregnancy rate at 9 months in patients who had undergone surgical destruction of endometriotic deposits (and any adhesions present) compared with the control (no treatment) arm (37.5% vs 22.5%). The number needed to treat to create a pregnancy was 7.7 (Marcoux et al 1997). However, a smaller, prospective randomized controlled trial from Italy did not show any difference in pregnancy rates between the treatment and control groups (19.6% vs 22.2%) (Parazzinni 1999). There is a need for more large randomized controlled trials to investigate the role of surgery in such patients.

Conclusions

To date, it is not known how mild endometriosis (without tubo-ovarian disease or adhesions) causes infertility, but it is recognized that such patients have a reduced fecundity rate. Until the underlying cause (if any) is found and appropriate corrective therapies are available, such asymptomatic patients are best treated along the lines of unexplained infertile couples (see Chapters 20 and 22) with treatment options based on age and duration of infertility.

Diagnosis

Symptomatic pointers

No single symptom is pathognomic of endometriosis, but severe dysmenorrhoea (pain sufficient to require time off work and/or to interfere with normal everyday activity) is highly predictive. Dyspareunia and pelvic pain are less predictive in the absence of severe dysmenorrhoea (Overton and Kennedy 1993). These gynaecological symptoms may, however, be of diagnostic help in the suspicion of endometriosis, which should be a differential diagnosis in any patient presenting with worsening dysmenorrhoea, pelvic pain and/or dyspareunia or with other cycle-associated symptoms relating specifically to the bowel, bladder or localized skin lesions (see Table 33.2 and Box 33.1). In endometriosis, the associated dysmenorrhoea extends to the pre- and postmenstrual phase, and is typically of secondary onset and progressive rather than being present from the onset of the menarche. In women presenting with pelvic pain, a history of whether or not this relates to the menstrual cycle is helpful in differentiating other aetiological causes of pain. In those with associated marked bowel symptoms, a trial of treatment for irritable bowel syndrome may be worthwhile before considering referral for diagnostic laparoscopy, although other pathologies may be present concurrently (see Box 33.2).

Box 33.1 Symptoms suggestive of the presence of endometriosis

Pelvic endometriosis

Morphology of the typical black lesions

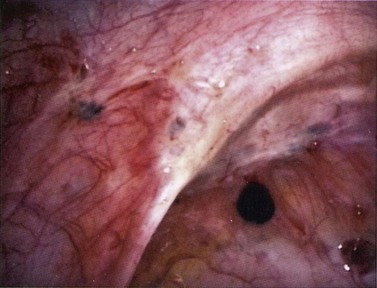

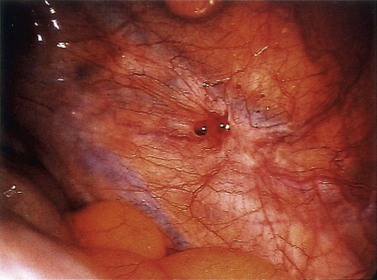

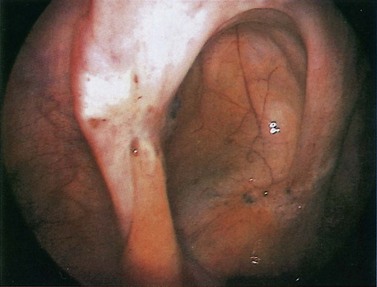

The typical peritoneal endometriotic lesion is described as a ‘powder burn’ which results from tissue bleeding and retention of blood pigments, producing a brown–black discoloration of the tissue. In the early stages, these lesions may appear more pink, red and haemorrhagic, and develop into brown–black lesions with increasing time. Eventually, discoloration disappears altogether and a white plaque of old collagen is all that remains of the endometriotic implant (Figure 33.2).

Classification and morphology of subtle appearances

More recently, more subtle laparoscopic appearances have been reported which were confirmed on biopsy as being due to endometriosis (Donnez and Nisolle 1991). The subtle forms are more common and may be more active and more important than the puckered black lesions that represent the later stages of the disease. These other peritoneal lesions include red lesions and white lesions.

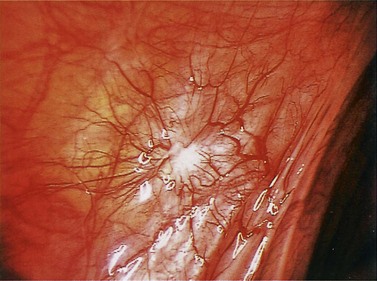

Red lesions

Figure 33.3 Active endometriosis on the uterosacral ligament.

Source: Overton C, Davis C, McMillan L, Shaw RW 2007 An Atlas of Endometriosis, 3rd edn. Informa Healthcare, London.

White lesions

Ovarian endometriosis

Superficial endometriosis

Superficial implants on the ovary resemble implants in other peritoneal sites. Comparable features are typical black, red or white lesions (Figure 33.8).

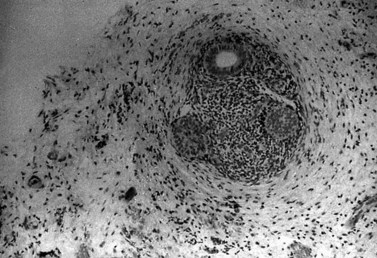

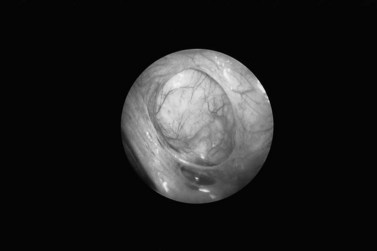

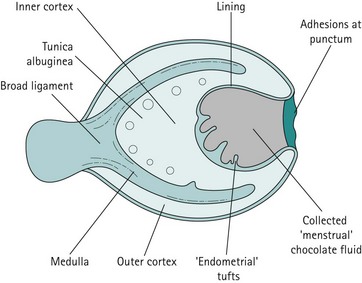

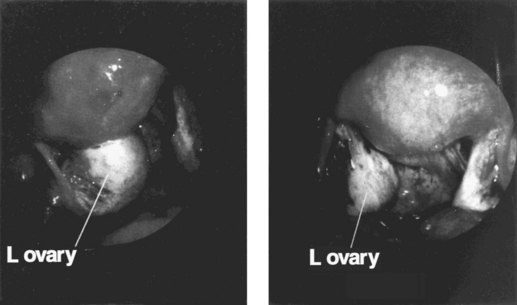

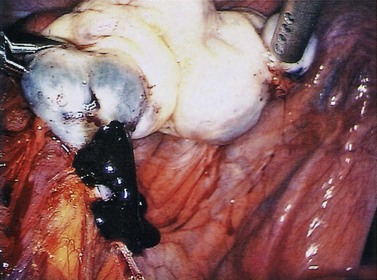

Endometrioma

The pathogenesis of the typical ovarian endometriotic cyst or endometrioma has now been clarified. It is a process originating from a free superficial implant which is in contact with the ovarian surface and is sealed off by adhesions (Figure 33.9). A pseudocyst is thus formed by accumulation of menstrual debris from shedding and bleeding of the small implant, resulting in fluid collection. Progressive invagination of the ovarian cortex occurs and the associated inflammatory reactive tissue progressively thickens the inverted cortex. Outgrowths through the endometrial epithelium, with or without stroma, extend over the surface or become embedded in the fibroreactive tissue covering the wall. This pathogenesis explains the typical features of an endometrium such as frequent location of the cyst, adhesions on the anterior side of the ovary opposing the posterior side of the parametrium or, when on the posterior aspect of the ovary, adhesions to the ovarian fossa. The contents of the cyst are, to a large extent, fluid which represents the debris from cyclical menstruation (Figures 33.10 and 33.11).

Figure 33.10 Left ovarian endometrioma.

Source: Overton C, Davis C, McMillan L, Shaw RW 2007 An Atlas of Endometriosis, 3rd edn. Informa Healthcare, London.

Ovarian endometriomas rarely occur in the adolescent, but incidence increases with age. Laparoscopic features of a typical endometrioma include ovarian cysts not greater than 12 cm in diameter, adhesions to the pelvic side wall and/or the posterior broad ligament, powder burns, minute red or blue spots with adjacent puckering on the surface, and the presence of the characteristic tarry, thick, chocolate-coloured fluid content (see Figure 33.10).

Extrapelvic endometriosis

Involvement in surgical scars

Endometriosis in surgical scars has been reported in the umbilicus or other port sites following laparoscopy, in abdominal incisions following gynaecological surgery and caesarean section, and in the perineum within episiotomy scars following childbirth (Figure 33.12). Such patients present with a painful, palpable swelling, usually more symptomatic at the time of menstruation. Occasionally, some women report discharge or cyclical bleeding occurring perimenstrually from the lesions. While medical treatment will control the symptoms with effective suppression of menstruation, surgical excision of the nodule will normally be necessary in the long term.

Non-invasive methods of diagnosis

Serum markers: CA125

The most widely used serum marker for endometriosis has been the monoclonal antibody OC125, raised against a human ovarian cancer cell line containing the antigen designated ‘CA125’. CA125 is a high-molecular-weight glycoprotein found in over 80% of cases of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Investigation leads to the conclusion that CA125 is possessed by many tissues present in the pelvis, as well as more distant sites including the pericardium and the pleura. Moderate elevation of serum CA125 has been observed in endometriosis, particularly in patients with severe disease (Barbieri et al 1986, Pittaway and Douglas 1989). In these studies, serum levels in excess of 35 u/ml were used as a cut-off point, but sensitivity and specificity have proved inadequate for the use of CA125 as a screening test for endometriosis. However, in individuals in whom the disease has been confirmed and treated, an increase in serum levels above 35 u/ml may be a useful marker of disease recurrence.

Monocyte chemotactic protein-1

Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) is a member of the small inducible gene family which plays a role in the recruitment of monocytes to sites of injury and inflammation. Levels of MCP-1 have been shown to be increased in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis (Arici et al 1997) and in the serum of such patients compared with controls (Pizzo et al 2002), particularly in patients with early disease. Further investigation needs to be undertaken to evaluate the potential value of measuring MCP-1 in the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis.

Imaging techniques

Ultrasound

Ultrasound examination of the pelvis may be useful in delineating the presence and aetiology of ovarian cystic structures. The characteristic pictures on ultrasound are different when there is a large proportion of blood, such as haemorrhagic corpus luteum cysts or endometriomas, which in a minority of cases may be echo free. However, the walls of an endometrioma are irregular as opposed to the smooth wall of the simple ovarian cyst. The most common pattern is for the chocolate cyst to contain low-level echoes or lumps of dense high-level echoes representing blood clots. The picture may sometimes be confused if there are several cysts in different phases of evolution (see Figure 33.13).

Figure 33.13 Transvaginal ultrasound scan showing the typical ground-glass appearance of endometrioma.

Source: Overton C, Davis C, McMillan L, Shaw RW 2007 An Atlas of Endometriosis, 3rd edn. Informa Healthcare, London.

Transrectal ultrasound may be of value before surgery in patients in whom rectal/rectovaginal septum involvement is suspected. This method permits measurement of the distance between the lesion and anal verge, as well as assessment of extrinsic compression and lesions in the rectal submucosal layer (Abrão et al 2004). This method is limited to evaluating the rectosigmoid and retrocervical region. It is advisable to undertake such examinations 1 h after a simple rectal enema.

Computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance imaging

Ultrasound, CT and MRI scanning do not appear to be of any help in the diagnosis of peritoneal endometriosis, the deposits of which are too small to be detected by current technology, although various strategies utilizing enhancement agents are being investigated. However, MRI of the pelvis is an additional tool for the diagnosis of pelvic deep infiltrating endometriosis (Bazot and Darai 2005). MRI is unable to precisely define the intestinal layer affected by the lesion, and rectosigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy may be necessary. Even when cyclical rectal bleeding occurs at menstruation, no overt mucosal lesion may be visualized in such patients since the lesions are submucosal. However, external compression or stricture formation may be seen and may also be demonstrated by barium enema studies.

Classification Systems

Over the last three decades, various classification systems have been proposed which attempt to standardize criteria on which the severity of endometriosis could be based. Such a system, if available, would help in the critical assessment of performance of various forms of treatment, and hopefully provide meaningful prognostic indicators. No classification system so far devised has received uniform acceptance; all have suffered from various pitfalls which make it difficult to compare treatment results. The most recent attempt to provide a standardized classification for uniform use has been the Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine Classification of Endometriosis (American Society for Reproductive Medicine 1996), shown in Figure 20.4. This serves to record the sites of deposits accurately and makes some effort to differentiate between superficial and deep-seated disease, as well as the presence or absence of adhesions. Whilst it offers a differential weighting to the score given to different types of endometriosis, it must be appreciated that these scores are arbitrary. Classification of the extent of the disease as minimal, mild, moderate or severe is certainly helpful in explaining the problem to the patient, and perhaps in determining whether a medical, surgical or combined medical and surgical approach is the most logical treatment step, at least in relation to fertility outcome.

In addition to the Revised American Fertility score, it may be helpful to chart the exact sites of all implants and their sizes; a method used in the scheme of Additive Diameter of Implants (ADI score) described by Doberl et al (1984), gives a simple quantitative valuation of alteration of the volume of endometriotic disease, although not the activity. For each square millimetre of disease, a score of 1 is given. The ADI score helps to quantify the volume of disease and may be useful in evaluating the response to treatment options.

Treatment: General Principles

Endometriosis is a particularly difficult disease to treat. Often, response to therapy relies on recognition of the disease in its earliest possible stages. With most treatment modalities, there is eventual recurrence in up to 60% of cases. Thus, there is no known permanent cure and eventually clinicians have to proceed to surgical oophorectomy in selected cases; this offers the most effective available treatment to date. In addition, in minimal and mild disease (according to the Revised American Fertility Society Classification), particularly in asymptomatic cases presenting with infertility alone, controversy exists as to whether treatment should be given, since no control studies have shown a significant increase in fertility rates following such ovarian-suppression therapies. However, placebo-controlled studies in such cases have shown that endometriosis tends to be a progressive disease for many patients (Thomas and Cooke 1987), and hence treatment may at least arrest progression or eradicate disease for significant intervals.

The treatment should be individualized, taking into account the patient’s age, wish for fertility, severity of symptoms and extent of disease (see Box 33.3). An important aspect of therapy is a sympathetic approach, with adequate counselling and explanation to the patient that will also ensure her compliance whilst on therapy.

Medical Treatments

The treatment of endometriosis has undergone a remarkable evolution in the last 40 years. In the past, testosterone, diethylstilboestrol and high-dose combination oestrogen–progestogen pill preparations were used with some success. However, therapies which induce decidualization (pseudopregnancy regimes) or suppress ovarian function (pseudomenopausal regimes) appear to offer the best chance of inducing clinical remission of endometriosis (Table 33.5).

Table 33.5 Various hormonal states and their effects upon normal endometrium and ectopic endometrial deposits

| Hormonal state | Effects on endometrium | Effects on endometriotic implants |

|---|---|---|

GnRH, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system.

Gestagen and antigestagen treatment

The oral progestogens used most commonly to attempt to induce amenorrhoea are:

Long-acting depot preparations of progestogens (Depo-Provera 150 mg, 3 monthly) can be used. However, the author’s personal experience has been that in order to avoid the initial problems (e.g. erratic/irregular vaginal bleeding), this may be best commenced once amenorrhoea has been achieved with other agents (e.g. GnRH analogues) for a few months. Depo-Provera has been shown to be as effective as the combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) or danazol in reducing endometriosis-associated pain (Vercellini et al 1996).

Levonorgestrel intrauterine system

The levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) was introduced as a long-acting contraceptive coil method, but its utility as a treatment option in gynaecology has been expanded into the treatment of menorrhagia due to dysfunction (unexplained) causes (see Chapter 31) and more recently in the treatment of endometriosis.

Effectiveness data come from two randomized controlled trials. In a study comparing LNG-IUS with expectant management, significantly lower pain scores were achieved in the LNG-IUS women at 12 months (Vercellini et al 2003). In the second trial, LNG-IUS was compared with GnRH analogue; after 6 months of treatment, both treatments were equally effective in reducing pain scores (Petta et al 2005).

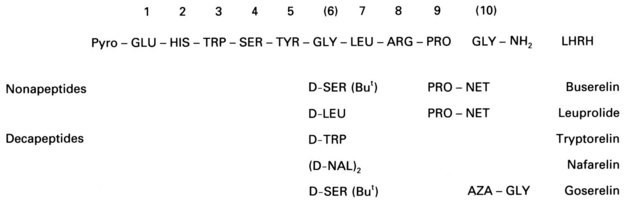

Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonists

Surgical castration is known to be an effective therapy for severe endometriosis. Thus, the possibility of inducing a reversible medical castration with the continued administration of GnRH agonists has been investigated as an alternative therapy in endometriosis. Modification of the native GnRH molecule with substitution, particularly in positions 6 and 10, with alternative amino acids produces agonistic analogues with a reduced susceptibility to degradation and hence a prolonged therapeutic half-life (Figure 33.14). Continued administration of these analogues induces pituitary gonadotrophin desensitization via downregulation of GnRH receptors and an eventual state of hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism. Reduced gonadotrophic stimulation of the ovaries leads to cessation of follicular growth and reduction in ovarian steroidogenesis, with circulating 17β-oestradiol levels falling to those observed in the postmenopausal range (typically less than 100 pmol/l).

A large amount of data has now appeared in the literature from both controlled and randomized comparative trials of GnRH analogues and danazol (for review, see Shaw 1995). These trials have all confirmed the value of GnRH analogues for the treatment of endometriosis. Rapid and effective symptomatic relief is achieved with these agents, as well as a marked degree of resolution of the endometrial deposits in the majority of patients. However, for both symptomatic relief and the resolution of endometrial deposits, there is essentially no significant difference in comparative trials between GnRH analogues and danazol. However, patient acceptability and the profile of side-effects may be slightly in favour of GnRH analogues (Matta and Shaw 1987, Henzl et al 1988).

Metabolic side-effects include (as in the menopause) increased excretion of urinary calcium. Over a 6-month period, there is a 3–5% loss in the vertebral trabecular bone density of the lumbar spine as assessed by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. In most patients, the bone density changes induced following a 6-month course of therapy with GnRH analogues are reversed 6 months after return of ovarian function (Matta et al 1987, Henzl et al 1988). However, the implications of such changes in calcium homeostasis with prolonged and repetitive treatment with GnRH analogues are being further investigated. This has led to the development of protective ‘add-back’ regimens which reduce the symptomatic effects of the GnRH-agonist-induced hypo-oestrogenism, particularly the frequency of hot flushes and bone loss, but do not result in reduced therapeutic effectiveness on symptom relief or implant resolution. A recent meta-analysis of 15 studies assessing GnRH agonists with add-back with oestrogen and progestogen showed protection to the lumbar spine for up to 12 months following cessation of treatment (Sagsveen et al 2003).

Danazol

Objective resolution of endometriotic lesions has been observed at post-treatment laparoscopic evaluation in between 70% and 95% of patients, depending upon the stage of the disease (Barbieri et al 1982). However, recurrence rates of up to 40% have been reported in the 36 months after completion of a course of danazol.

Gestrinone

Gestrinone is a synthetic trienic 19-norsteroid (13-ethyl-17-α-ethinyl-17-hydroxy-gona-4,o,Il-triene-3-one). It has been shown in clinical trials to be another effective clinical treatment for endometriosis (Thomas and Cooke 1987). The drug exhibits mild androgenic and antigonadotrophic properties. The combined effect is to induce progressive endometrial atrophy. Gestrinone has a high binding affinity for progesterone receptors; it also binds to androgen receptors but not to oestrogen receptors. The combined endocrine effect of gestrinone therapy is similar to that of danazol in that the midcycle gonadotrophin surge is abolished, although basal gonadotrophin levels are not significantly reduced, together with inhibition of ovarian steroidogenesis and reduction of sex-hormone-binding globulin levels. Gestrinone has a prolonged half-life and may be administered orally at a dosage of 2.5–5.0 mg twice weekly for a period of 6–9 months in patients with endometriosis. This dosage schedule effectively induces endometrial atrophy, with 85–90% of patients becoming amenorrhoeic within 2 months.

Gestrinone compares favourably with danazol in terms of both symptomatic relief and resolution of endometrial deposits (Mettler and Semm 1984).

Aromatase inhibitors

Limited data have been published on the use of aromatase inhibitors in endometriosis. A meta-analysis of 40 women from seven published case studies utilizing aromatase inhibitors in combination with progestogens, COCP or GnRH-A reported reduced mean pain scores and lesion size, and improved quality-of-life scores (Nawathe et al 2008). More data are needed to establish the efficacy and safety of aromatase inhibitors, and which combination of drugs produces the best results.

Surgical Treatment

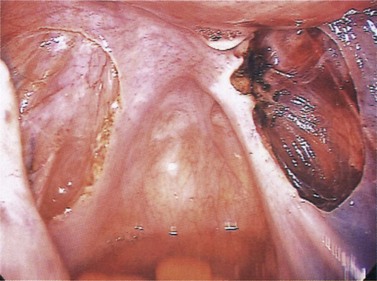

Conservative surgery

With the increasingly widespread availability of laparoscopic expertise, improved instrumentation and experience of laser technology, minimal access surgery is becoming a more popular treatment option. There have been few appropriately conducted randomized trials, but one small double-blind placebo-controlled study measured pain relief following laser ablation and/or laparoscopic uterosacral nerve ablation or placebo (no treatment). At 6 month follow-up, 53% of those treated with laser compared with only 23% from the placebo diagnostic laparoscopy group had improvements in symptoms (Sutton et al 1994). It was of interest that in minimal disease, only 38% of women had a reduction in pain. Therefore, this approach appeared to be more effective in reducing pain symptoms in women with more severe disease.

Sutton et al (1997) published the results of a longer term follow-up of this cohort of patients. Sadly, 1 year after the initial treatment, 44% had recurrence of pain requiring additional treatment. The reasons for failure of the surgical approach may result from missing lesions, incomplete destruction and, of course, recurrence of the disease.

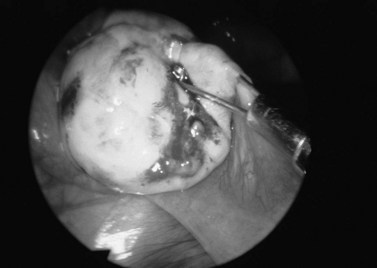

An alternative approach to ablation of lesions is excision. Advocates of this approach argue that excision is the only way to ensure complete treatment because it may be difficult to determine the depth of the implant. Local excision can achieve good results in terms of pain reduction — 67% improvement up to 12 months (Wykes et al 2006) — but another study reported a high reoperation rate with longer term follow-up of 46% at 5 years and 55% at 7 years (Shakiba et al 2008) (see Figures 33.15 and 33.16).

Laparoscopic uterosacral nerve ablation

In a double-blind randomized controlled study, the addition of laparoscopic uterosacral nerve ablation to laparoscopic laser vaporization of endometriotic lesions alone was not found to improve pelvic pain responses (Sutton et al 2001). This procedure should not be performed if the uterosacral ligaments have a normal appearance, whilst excision of deep infiltrating lesions on the uterosacral ligament seems to be beneficial.

Surgical treatment of endometriomas

The definitive treatment of the typical endometrioma is the surgical release of the adhesions and fibrosis at the site of invagination, and the eversion of the invaginated cortex. Simply puncturing and draining the endometrioma, whether this is followed by GnRH agonist therapy or not, has no beneficial effects in the long term (Vercellini et al 1992). Medical treatment is highly effective for the destruction of active implants located on the surface of the normal ovarian cortex. However, when a definite endometrioma is present, surgery is necessary. This can be performed laparoscopically for smaller endometriomas using laser destruction. With endometriomas larger than 3 cm in diameter, treatment may be facilitated to enable laparoscopic surgery if, following initial drainage, patients are pretreated for 3 months with a GnRH agonist prior to laser ablation (Donnez et al 1990).

Whatever the surgical approach, be it minimal access or open laparotomy, if dense and extensive adhesions are present at the time of original surgery, it is likely that such patients will have recurrence of adhesions with attendant problems of fixity of the ovary following such approaches (Shaw et al 2001).

Recurrent Endometriosis

After medical suppression of the disease or surgical destruction of all visible deposits, residual viable (microscopic) implants can regenerate once ovarian function is re-established. In other cases, new disease develops at new sites, perhaps indicating the potential for an entire ‘field change’ within the pelvic peritoneum. The degree of differentiation of a lesion may also correlate with persistence of disease following medical therapy. Two-thirds of lesions that were most highly differentiated disappeared following 6 months of medical therapy, whilst three-quarters of poorly differentiated lesions persisted (Schweppe 1984).

KEY POINTS

Abrão MS, Neme RM, Averbach M, Petta CA, Aldrighi JM. Rectal endoscopic ultrasound with a radial probe in the assessment of rectovaginal endometriosis. Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. 2004;11:50-54.

Adamson GD, Pasta DJ. Surgical treatment of endometriosis-associated infertility: meta-analysis compared with survival analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;171:1488-1504.

American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Revised ASRM classification of endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility. 1996;67:817-821.

Arici A, Oral E, Attar E, Tazuke SI, Olive DL. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 concentration in peritoneal fluid in patients with endometriosis and its modulation in human mesothelial cells. Fertility and Sterility. 1997;67:1065-1072.

Barbieri RL, Evans S, Kistner RW. Danazol in the treatment of endometriosis: analysis of 100 cases with a 4-year follow-up. Fertility and Sterility. 1982;37:737-749.

Barbieri RL, Niloff JM, Bast RC, Shaetzl E, Kistner RW, Knapp RC. Elevated serum concentrations of CA-125 in patients with advanced endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility. 1986;45:630-634.

Bazot M, Darai E. Sonography and MR imaging for the assessment of deep pelvic endometriosis. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 2005;12:178-185.

Dmowski WP, Steele RW, Baker GF. Deficient cellular immunity in endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1981;141:377-383.

Doberl A, Bergquist A, Jeppson S, Koskimies AI, Ronnberg L, Segerbrand E. Repression of endometriosis following shorter treatment with or lower dose of danazol. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1984;123(Suppl):51-58.

Donnez J, Nisolle M, Clerckx F, et al. The ovarian endometrial cyst: combined (hormonal and surgical) therapy. In: Brosens I, Jacobs HS, Runnebaum B, editors. LHRH Analogues in Gynaecology. Carnforth: Parthenon; 1990:165-175.

Donnez J, Nisolle M. Appearance of peritoneal endometriosis. Brussels: Third Laser Surgery Symposium, March 1991; 1991.

Drake TS, O’Brien WF, Ramwell P, Metz SA. Peritoneal fluid thromboxane B2 and 6-keto-prostaglandin F1 alpha in endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1981;140:401-404.

Eskanazi B, Warner ML. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstetrics and Gynecological Clinics of North America. 1997;24:235-258.

Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. The Lancet. 2004;364:1789-1799.

Halme J, Beecher S, Wing R. Accentuated cyclic activation of peritoneal macrophages in patients with endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1984;148:85-90.

Halme J, Becher S, Haskill S. Altered life span and function of peritoneal macrophages: a new hypothesis for pathogenesis of endometriosis. Toronto: Society of Gynecologic Investigation; 1986. Abstract 48

Henzl MR, Corson SL, Moghissi K, Buttram VC, Bergquist C, Jacobson C. Administration of nasal nafarelin as compared with oral danazol for endometriosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;318:485-489.

Houston DE. Evidence for the risk of pelvic endometriosis by age, race and socioeconomic status. Epidemiology Reviews. 1984;6:167-191.

Hughes EG, Fedorkow DM, Collins JA. A quantitative overview of controlled trials in endometriosis-associated infertility. Fertility and Sterility. 1993;59:963-970.

Ingamells S, Thomas EJ. Infertility and endometriosis. In: Shaw RW, editor. Endometriosis — Current Understanding and Management. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1995:147-167.

Kennedy SH, Soper NDW, Mojiminiyi OA, Shepstone BJ, Barlow DH. Immunoscintigraphy of ovarian endometriosis. A preliminary study. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1988;95:693-697.

Kistner RW. Sciarra J, editor. Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Vol. 1. Harper and Row, London, 1977.

Koninckx PR, de Moor P, Brosens IA. Diagnosis of the luteinizing unruptured follicle syndrome by steroid hormone assays in peritoneal fluid. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1980;87:929-934.

Landazabal A, Diaz I, Valbuena D. Endometriosis and in vitro fertilisation: a meta-analysis. Human Reproduction. 1999;14:181-182.

MacLaverty CM, Shaw RW. Pelvic pain and endometriosis. In: Shaw RW, editor. Endometriosis — Current Understanding and Management. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1995:112-146.

Mahmood TA, Templeton A. The impact of treatment on the natural history of endometriosis. Human Reproduction. 1990;5:965-970.

Marcoux S, Maheux R, Berube S. The Canadian collaborative group on endometriosis laparoscopic surgery in infertile women with minimal–mild endometriosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337:217-222.

Matta WH, Shaw RW. A comparative study between buserelin and danazol in the treatment of endometriosis. British Journal of Clinical Practice. 1987;41(Suppl 48):69-73.

Matta WM, Shaw RW, Hesp R, Katz D. Hypogonadism induced by luteinizing hormone releasing hormone agonist analogues: effects on bone density in premenopausal women. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1987;294:1523-1524.

Meldrum DR, Shamonki IM, Clarke KE 1977 Prostaglandin content of ascitic fluid in endometriosis: a preliminary report. 25th Annual Meeting of the Pacific Coast Fertility Society, Palm Springs, CA.

Mettler L, Semm K. Three-step therapy of genital endometriosis in cases of human infertility with lynestrenol, danazol or gestrinone administration. In: Raynaud JP, Ojasoo T, Martini L, editors. Medical Management of Endometriosis. New York: Raven Press; 1984:233-247.

Meyer R. Uber den Staude der Frage der Adenomyosites Adenomyoma in allegemeinen und Adenomyometitis Sarcomastosa. Zentralblatt für Gynäkologie. 1919;36:745-759.

. The etiology of endometriosis: environment. Blackwell Publishing, Sydney, Australia, 2008;49-67.

Miyazawa K. Incidence of endometriosis among Japanese women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1976;48:407-409.

Nawathe A, Patwardhan S, Yates D, Harrison GR, Khan KS. Systematic review of the effects of aromatase inhibitors on pain associated with endometriosis. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;115:818-822.

Overton C, Kennedy S. Endometriosis and pelvic pain. Contemporary Reviews of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1993;5:94-97.

Overton C, Davis C, McMillan L, Shaw RW. An Atlas of Endometriosis, 3rd edn. London: Informa Healthcare; 2007.

Parazzinni F. Ablation of lesions or no treatment in minimal–mild endometriosis in infertile women: a randomized trial. Human Reproduction. 1999;14:1332-1334.

Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abra MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial for a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Human Reproduction. 2005;20:1993-1998.

Pittaway DE, Douglas JW. Serum CA-125 in women with endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain. Fertility and Sterility. 1989;51:68-70.

Pizzo A, Salmeri FM, Ardita FV, Sofo V, Tripepi M, Marsico S. Behaviour of cytokine levels in serum and peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 2002;54:82-87.

Rock JA, Dubin NM, Ghodgaonkar RB, Bergquist CA, Erozan YS, Kimball AWJr. Cul-de-sac fluid in women with endometriosis: fluid volume and prostanoid concentration during the proliferative phase of the cycle — days 8–12. Fertility and Sterility. 1982;37:747-752.

Sagsveen M, Farmer JE, Prentice A, Breeze A 2003 Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues for endometriosis: bone mineral density. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD001019.

Sampson JA. Perforating haemorrhagic (chocolate) cysts of the ovary, their importance and especially their relation to pelvic adenomas of endometrial type. Archives of Surgery. 1927;3:245-323.

Schifrin BS, Erez S, Moore JG. Teenage endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1973;116:973-980.

Schweppe KW. Morphologie und Klinik der Endometriose. Stuttgart: F.K. Schattauer Verlag; 1984. pp 198–207

Shakiba K, Bena JF, McGill KM, Minger J, Falcone T. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: a 7 year follow-up on the requirement for further surgery. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;111:1285-1292.

Shaw RW. Evaluation of treatment with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues. In: Shaw RW, editor. Endometriosis — Current Understanding and Management. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1995:206-234.

Shaw RW, Garry R, McMillan L, et al. A prospective randomized open study comparing goserelin (Zoladex) plus surgery and surgery alone in the management of ovarian endometriomas. Gynaecological Endoscopy. 2001;10:151-157.

Simpson JL, Elias S, Malinak LR, Buttram VCJr. Heritable aspects of endometriosis. I. Genetic studies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1980;137:327-331.

Simpson JL, Malinak LR, Elias S, Carson SA, Redvary RA. HLA associations in endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1984;148:395-397.

Strathy JH, Molgaard GA, Coulam CB, Molton LJIII. Endometriosis and infertility: a laparoscopic study of endometriosis among fertile and infertile women. Fertility and Sterility. 1982;38:667-672.

Sutton CJ, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomized double blind, controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal mild, and moderate endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility. 1994;62:696-700.

Sutton CJ, Polley AS, Ewen SP, Haines P. Follow-up report on a randomized controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal to moderate endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility. 1997;68:1070-1074.

Sutton C, Pooley AS, Jones KD, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial of laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Gynecological Endoscopy. 2001;10:217-222.

Templeton A, Morris DJK, Parslow W. Factors that affect the outcome of in vitro fertilisation treatment. The Lancet. 1996;348:1402-1406.

Thomas EJ, Cooke ID. Impact of gestrinone on the course of asymptomatic endometriosis. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1987;294:272-274.

Tyson JEA. Surgical consideration in gynecologic endocrine disorders. Surgical Clinics of North America. 1974;54:425-442.

Vercellini P, Vendola N, Bocciolone L, Colombo A, Rognoni MT, Bolis G. Laparoscopic aspiration of ovarian endometriomas: effect with postoperative gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist treatment. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1992;37:577-580.

Vercellini P, De Giorgi O, Oldani S, Cortesi I, Panazza S, Crosignani PG. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate versus an oral contraceptive combined with low-dose danazol for long-term treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;175:396-401.

Vercellini P, Frontino G, De Giorgi O, et al. Comparison of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus expectant management after conservative surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertility and Sterility. 2003;80:305-309.

Vernon M, Beard J, Graves K, Wilson EA. Classification of endometriotic implants in morphologic appearance and capacity to synthesize prostaglandin F. Fertility and Sterility. 1986;46:801-805.

Wykes CB, Clark TJ, Chakravati S, Mann CH, Gupta JK. Efficacy of laparoscopic excision of visually diagnosed peritoneal endometriosis in the treatment of chronic pelvic pain. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2006;125:129-133.