13

Endometriosis

Introduction

Chronic pelvic pain is defined as constant or intermittent pain in the lower abdomen or pelvis of a woman of at least 6 months’ duration and not associated with pregnancy. The causes of chronic pelvic pain include: endometriosis and adenomyosis; ovarian cysts; scar tissue and adhesions; irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); interstitial cystitis; chronic pelvic infection; musculoskeletal and nerve entrapment. Chronic pelvic pain presents in primary care as frequently as migraine or low-back pain, and may significantly impact on a woman’s ability to function.

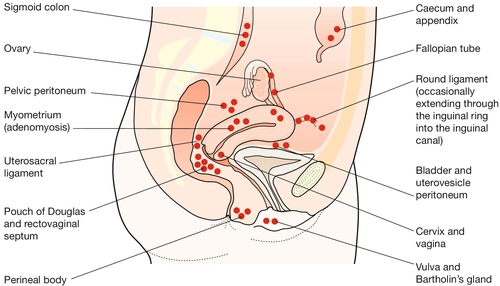

Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, which induces a chronic inflammatory reaction. It usually lies within the peritoneal cavity and predominantly in the pelvis, commonly on the uterosacral ligaments behind the uterus (Fig. 13.1). Rarely, it can also be found in distant sites such as the umbilicus, abdominal scars, perineal scars and even the pleural cavity and nasal mucosa. Like the true endometrium, it responds to cyclical hormonal changes and it bleeds at menstruation. Such bleeding may cause symptoms.

Adenomyosis occurs when there is endometrial tissue within the myometrium of the uterus. The uterus is enlarged and feels ‘boggy’. There is painful and heavy menstruation. Adenomyosis is difficult to diagnose clinically and is usually only apparent retrospectively, with histological examination of the uterus after hysterectomy. It is commonly considered to be a separate entity from endometriosis, occurring in a different population and having a different aetiology.

Incidence

The reported incidence of endometriosis varies widely; for example among asymptomatic fertile women undergoing laparoscopic sterilization procedures, the incidence of endometriosis ranges from 4–43%. Endometriosis is more commonly identified in infertile women. Most cases of endometriosis are diagnosed in women aged 25–35 years, although the symptoms of endometriosis can present as early as the onset of puberty. As it is oestrogen dependent, it is rarely diagnosed postmenopausally, but recurrence has been associated with the use of hormone replacement therapy.

Aetiology

The precise aetiology of endometriosis remains unclear, with no single explanation reliably explaining all its features. Sampson’s ‘implantation’ theory (see History box) postulates that endometrial fragments flow in a retrograde manner along the fallopian tube during menstruation, ‘seeding’ themselves on the pelvic peritoneum. In support of this theory is the fact that it is sometimes possible to see blood flowing from the fimbrial end of the fallopian tube if a laparoscopy is carried out during menstruation – it is believed that retrograde menstruation occurs in 90% of menstruating women. Seeding is also observed onto scars such as after hysterectomy or caesarean section, or on perineal scars after delivery, and there is some animal research in which endometrial tissue has been surgically implanted directly onto the peritoneum. Other animal research, where retrograde menstruation has been surgically created, found that endometriosis developed in 50% of cases.

This theory, however, cannot be the only mechanism of endometriosis formation, as endometriosis has been reported in women with congenitally obstructed fallopian tubes. Meyer’s ‘coelomic metaplasia’ theory (see History box) proposes that cells of the original coelomic membrane transform to endometrial cells by metaplasia, possibly as a result of hormonal stimulation or inflammatory irritation. This could explain the presence of endometriosis in nearly all the distant sites, although it is also possible that spread from the uterus to these distant sites occurs by venous or lymphatic microembolism.

In some instances, the presence of endometriosis may be explained by neoplasia. This is particularly so in the ovary, where a solitary ovarian endometrioma is sometimes included in the classification of ovarian neoplasia as the benign counterpart of endometrioid carcinoma.

The question remains as to why endometriosis becomes established in some, but not all, women and it is possible that there is some genetic or immunological predisposition to account for such wide variation. Endometriosis is significantly more common in first-degree relatives of women with the disease and twin studies also support a genetic basis.

Clinical presentation

In most instances, clinical presentation occurs because of pelvic disease. Endometriosis is the commonest cause of secondary dysmenorrhoea. There is usually a continuous, non-spasmodic pain, which is worse immediately before and throughout menstruation, and colicky dysmenorrhoea may also occur in association with heavy menstrual loss and the passage of clots. In addition, there may be dyspareunia, which may relate to endometriotic deposits in the pouch of Douglas or to ovarian endometriomas. Typically, this pain settles when the period ends, but some women also describe a continuous, lower abdominal pain that is not specifically related to their cycle or to sexual activity. The common presenting symptoms of endometriosis are outlined in Box 13.1.

One of the puzzles regarding endometriosis is the lack of correlation between the severity of these symptoms and the extent of the disease. Extensive deposits leading to the obliteration of the pouch of Douglas and involving the ovaries, fallopian tubes and other pelvic organs, may be completely asymptomatic; conversely, women with lesions only a few millimetres across may be debilitated by pain.

Menstrual disturbances may be associated with endometriosis, and in particular with adenomyosis. Where there is also significant ovarian involvement, the menstrual cycle may become erratic. Rarely, post-coital bleeding is experienced in the presence of endometriosis involving the ectocervix, or where deposits in the pouch of Douglas penetrate into the posterior fornix.

Endometriosis in distant sites is rare but may generate local symptoms, such as cyclical epistaxes with nasal deposits, or pneumothoraces with pleural deposits (‘catamenial pneumothorax’), or headaches and/or seizures with endometriosis in the brain. Monthly rectal bleeding may occur if the bowel mucosa is affected, or haematuria with bladder involvement.

Examination

The clinical diagnosis of endometriosis is aided by findings of:

![]() thickened pelvic ligaments, particularly the uterosacral ligaments, which may be nodular; on speculum examination, blue nodules may be seen in the posterior vaginal fornix

thickened pelvic ligaments, particularly the uterosacral ligaments, which may be nodular; on speculum examination, blue nodules may be seen in the posterior vaginal fornix

![]() a fixed (immobile) retroverted uterus

a fixed (immobile) retroverted uterus

![]() ovarian enlargement if there is an endometrioma.

ovarian enlargement if there is an endometrioma.

There may also be tenderness in the lateral and posterior fornices and with applied pressure on the uterosacral ligaments. Nodules are most reliably detected when clinical examination is performed during menstruation. Attempts to move the uterus may also provoke pain. This pain often resembles the presenting symptom, particularly when this was dyspareunia.

With the exception of visualizing endometriotic nodules, none of these features is diagnostic of endometriosis and conversely their absence does not exclude the disease. There are many other causes of pelvic pain, including IBS and recurrent urinary infection, which can confuse the differential diagnosis. In particular, chronic conditions such as pelvic inflammatory disease and adhesions mimic many features of endometriosis. Laparoscopy is therefore usually necessary to make the diagnosis.

Endometriosis and infertility

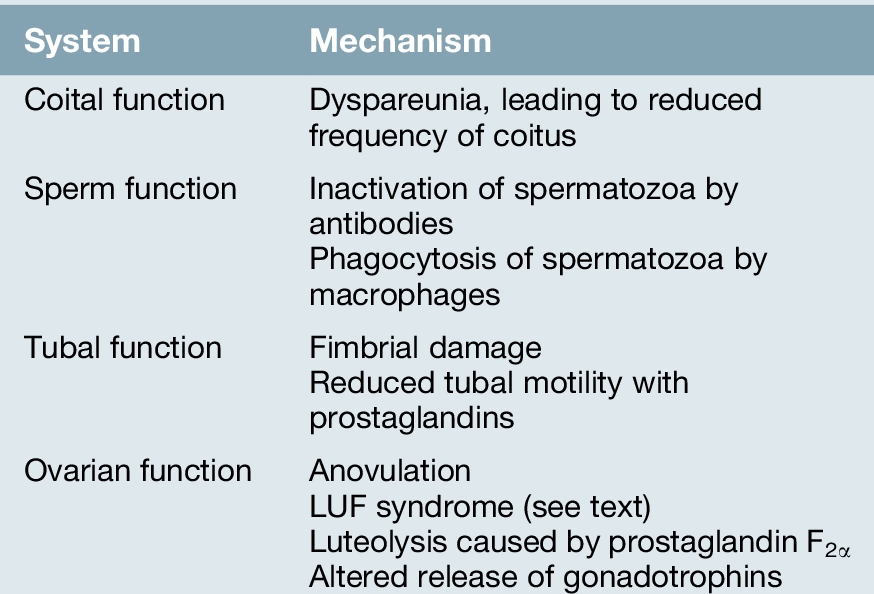

Endometriosis is commonly diagnosed in women who are undergoing laparoscopic investigations for infertility but who do not have specific symptoms. Although endometriosis and infertility are associated more commonly than can be explained by chance, the exact mechanism of their interrelationship is uncertain (Table 13.1).

While it is recognized that severe disease can cause infertility by forming periovarian and peritubular adhesions and by destroying ovarian tissue, the association between mild endometriosis and infertility is less clear. Theoretically, high prostaglandin production from endometriotic tissue could impede tubal motility, or the spermatozoa may be affected by adverse immunological factors.

Another possibility is that infertility caused by some unrelated factor may predispose to endometriosis simply because, in the absence of pregnancy and lactational amenorrhoea, the affected woman will have more periods. Other theories suggest that both endometriosis and infertility are manifestations of a third, unidentified problem. An association with the luteinized unruptured follicle (LUF) syndrome, in which follicular development proceeds along apparently normal lines but oocyte release does not occur, provides another explanation. As endometriosis is more common in this condition, it has been proposed that failure to release follicular fluid mid-cycle may result in a preferential environment for endometriosis to become established.

Investigation

Transvaginal ultrasound can detect gross endometriosis involving the ovaries (endometriomas or chocolate cysts) and occasionally the rectum, and MRI can delineate the extent of active endometriosis lesions greater than 1 cm in diameter in deep tissues, e.g. rectovaginal septum. Laparoscopy remains the traditional standard diagnostic method. Active endometriotic lesions are classically described as red, puckered and inflamed or ‘burnt match heads’ (cigarette burns). Inactive lesions look like scars. The degree to which laparoscopic visualization alone may be adequate, however, has been questioned (see Box 13.2) and it has been proposed that clinicians confirm a positive laparoscopy by histology of biopsies.

Little is known about the rate of progression of low-grade endometriosis, but a proportion of untreated patients may deteriorate over as little as 6 months. The prompt return of symptoms after treatment, seen in many patients, may represent re-extension of uneradicated residual disease.

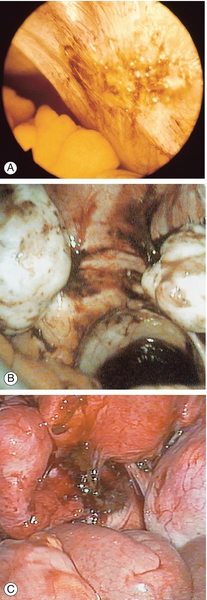

Fig. 13.2Peritoneal appearances of endometriosis.

Laparoscopic views show: (A) clear blisters (‘sago’ granules), ‘blood blisters’, yellow-brown patches, ‘powder burns’, atypical vascularity and telangiectasia; (B) bilateral endometriomas; (C) severe endometriosis with adhesions. (Parts (B) and (C) courtesy of Karl Storz Endoscopy (UK) Ltd.)

It is impossible to guarantee a cure after treatment. Routine repeat laparoscopy after completion of treatment, therefore, has limited prognostic value and is probably best reserved for those patients with recurrent symptoms.

Serum CA125 levels may be elevated in endometriosis, although measuring serum CA125 levels has no value as a diagnostic tool.

Management

Medical treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or simple analgesics is widely employed and many women will be self-prescribing prior to diagnosis. Medical treatment with ovulation suppression is most useful for symptomatic relief, but is of no value for the treatment of endometriosis in patients wishing to conceive. Treatment is usually limited to between 3 and 6 months. Surgical treatment may be conservative, with laser or diathermy ablation, or radical, involving hysterectomy and oophorectomy.

Medical treatment

Medical treatment is founded upon the observation that endometriosis improves during both pregnancy and the menopause; so creating a ‘pseudo-pregnancy’ with progestogens or combined oral contraceptives and a ‘pseudo-menopause’ with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, is appropriate and frequently effective. Ovulation suppression limits the likelihood of conception, but nonetheless, it is still advisable for women to use barrier methods of contraception (unless using the combined oral contraceptive as their treatment method). To avoid inadvertent administration during pregnancy, all therapies should be initiated within the first 3 days of the start of a menstrual period.

For symptomatic endometriosis, continuous progestogen therapy (e.g. medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg three times daily for 90 days) is most cost-effective, has fewer side-effects and is more suitable for long-term use compared with more expensive alternatives. Progestogens have a direct action on the endometrial target tissue by binding to progestogen receptors. This produces decidualization of the endometrial tissue, which then leads to subsequent necrosis. The combined oral contraceptive pill is also an appropriate alternative; it is usually taken continuously or in a tricycle regimen in order to induce amenorrhoea. The usual risk factors for the suitability or otherwise for using the combined pill should be evaluated, but if appropriate and symptoms are alleviated, it can be continued for several years or even longer.

Second-line drugs are the GnRH analogues (which can be administered by nasal spray, implants or injection), and the orally administered androgen, danazol. GnRH analogues bind to GnRH receptors in the pituitary, initially stimulating gonadotrophin release but rapidly desensitizing the pituitary to GnRH stimulation, thereby in turn suppressing gonadotrophin release and hence ovarian steroid secretion. The profound hypo-oestrogenic state produced not only affects endometrial tissue but also causes side-effects mimicking the climacteric. Therapy is limited to 4–6 months and it is routine to prescribe ‘add-back’ hormone replacement therapy to alleviate the predictable menopausal side-effects and negative effects upon bone density. The use of add-back therapy does not reduce the effect of treatment on pain relief. Danazol combines androgenic activity with anti-oestrogenic and anti-progestogenic activity, and it inhibits pituitary gonadotrophins. It has a relatively high incidence of androgenic and perimenopausal side-effects, and it is therefore rarely employed in current practice.

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) is an effective option to reduce endometriosis-associated pain. It is also useful to prevent the recurrence of endometriosis after surgical treatments.

Medical treatment can also be used as a diagnostic tool. By achieving amenorrhoea and symptom relief, then it is extremely likely that the symptoms were due to endometriosis. If symptoms persist, a review of the diagnosis is necessary and other causes of pelvic pain considered.

Surgical treatment

When continued fertility is required, conservative surgery is appropriate. This is usually carried out laparoscopically and includes diathermy destruction, laser vaporization, helium beam coagulation or excision of endometriosis deposits. It may bring about symptom relief and has a role in subfertile women (see below). Recurrence risks following conservative surgery are as high as 30%. Cystectomy rather than drainage and coagulation, should be performed for an ovarian endometrioma > 3 cm.

Hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy for women who have completed their childbearing is usually curative. Hormone replacement will be needed; although this may activate residual disease, the possibility may be minimized by using some form of combined preparation rather than an oestrogen-only form.

The surgical management of deep infiltrating endometriosis is complex and should be undertaken in an expert centre with the appropriate multidisciplinary expertise.

Fertility treatment

There is no evidence that medical treatment of endometriosis is of any value in the management of subfertility. Surgical ablation or excision of minimal and mild endometriosis does improve fertility, but whether surgery has a role in moderate and severe endometriosis is less clear. Surgical treatment of large ovarian endometriotic cysts probably enhances spontaneous pregnancy rates and will improve transvaginal access if in-vitro fertilization (IVF) is considered. In cases of moderate and severe endometriosis, assisted reproduction techniques should be considered as an alternative to surgery or following unsuccessful surgery.

Complications, prognosis and long-term sequelae

Depending upon the severity of the disease, adhesions and fibrosis may distort bowel, bladder, ureters and other neighbouring viscera, leading to chronic problems with these systems. The physical and psychological morbidity from long-term pain can be considerable.