DIABETES MELLITUS

Case vignette

A 58-year-old female presents with nausea and vomiting in the background of progressive exertional dyspnoea.She is a smoker with a 10-pack per year history. She was diagnosed with diabetes 2 years ago and has been managed on metformin 500 mg twice daily. On examination she has coarse crepitations in the lung bases bilaterally. She has an S3 gallop in the precordium. She is obese and has moderate bipedal pitting oedema. Blood pressure is 140/90 mmHg. On the ECG, ST segment depression is observed in the lateral leads. Her fasting blood sugar levels are 11.2 mmo/L with an Hb A1c of 8.2%. Serum troponin level is not elevated.

Approach to the patient

Diabetes is a very commonly encountered condition in the long case setting. Most diabetic patients have multiple associated medical conditions, and this makes them favourite long case material. A candidate is expected to be able to address diabetic cases thoroughly and extensively. Ascertain whether the patient has the metabolic syndrome (see box) that is associated with high cardiovascular risk. The following is a discussion of the integral issues that should never be missed in any diabetic case.

(Adapted from International Diabetes Federation 2006 Consensus worldwide definition of metabolic syndrome. Online. Available: http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/MetS_def_update2006.pdf)

(Adapted from International Diabetes Federation 2006 Consensus worldwide definition of metabolic syndrome. Online. Available: http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/MetS_def_update2006.pdf)

History

Ask about:

• when and how the diagnosis was made, and symptoms at presentation, such as loss of weight, polyuria, polydypsia, and other associated presenting features such as diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar coma and infection

• initial treatment, subsequent treatment and the current medical regimen

• age at disease onset

• the type of diabetes the patient has—this has implications for the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis and for the therapeutic regimens

• the insulin treatment, such as previous and/or current regimens, types of insulin, dose and frequency of administration, who injects the insulin, the method of delivery (pen or syringe) and adverse effects associated with insulin treatment

• medication history, in detail—note the different classes of drugs that have been used to treat the diabetes, and also other medications that would interfere with adequate glycaemic control

• the patient’s knowledge of and compliance with the diabetic diet, and knowledge of the concept of the glycaemic index of various carbohydrate-containing foods

• who monitors the blood sugar levels and how often this is done—ask for the most recent readings

• episodes of ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar coma and other acute events that have necessitated hospitalisation

• whether the patient suffers from hypoglycaemic episodes and how he or she recognises early warning signs, and what remedial measures the patient takes in such situations

• other vascular risk factors, such as smoking, hyperlipidaemia and hypertension

• diabetic complications:

– macrovascular complications—ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, intermittent claudication and stroke (remember that diabetic cardiomyopathy may dominate the picture, leading to silent ischaemic episodes)

– microvascular complications:

ocular complications—such as diabetic retinopathy. Ask how often the patient visits the ophthalmologist and the current level of vision and any visual symptoms. Ask about any laser therapy for diabetic retinopathy. While discussing the eye, ask about cataracts.

ocular complications—such as diabetic retinopathy. Ask how often the patient visits the ophthalmologist and the current level of vision and any visual symptoms. Ask about any laser therapy for diabetic retinopathy. While discussing the eye, ask about cataracts.

neurological complications—ask about peripheral paraesthesias, painful peripheries, burns, neuropathic ulcers and Charcot’s joints. Ask whether the patient has ever had nerve conduction studies done. Enquire about symptoms of autonomic neuropathy, such as persistent postural dizziness, bloating, nocturnal diarrhoea, impotence and incontinence.

neurological complications—ask about peripheral paraesthesias, painful peripheries, burns, neuropathic ulcers and Charcot’s joints. Ask whether the patient has ever had nerve conduction studies done. Enquire about symptoms of autonomic neuropathy, such as persistent postural dizziness, bloating, nocturnal diarrhoea, impotence and incontinence.

nephropathy—ask whether the patient has any urinary symptoms, such as frequency, polyuria and nocturia. Has the patient observed peripheral oedema that would suggest early-stage renal failure? Enquire about any previous investigations, such as 24-hour urinary collection for proteinuria, and whether the patient is aware of their level of renal function.

nephropathy—ask whether the patient has any urinary symptoms, such as frequency, polyuria and nocturia. Has the patient observed peripheral oedema that would suggest early-stage renal failure? Enquire about any previous investigations, such as 24-hour urinary collection for proteinuria, and whether the patient is aware of their level of renal function.

ocular complications—such as diabetic retinopathy. Ask how often the patient visits the ophthalmologist and the current level of vision and any visual symptoms. Ask about any laser therapy for diabetic retinopathy. While discussing the eye, ask about cataracts.

ocular complications—such as diabetic retinopathy. Ask how often the patient visits the ophthalmologist and the current level of vision and any visual symptoms. Ask about any laser therapy for diabetic retinopathy. While discussing the eye, ask about cataracts. neurological complications—ask about peripheral paraesthesias, painful peripheries, burns, neuropathic ulcers and Charcot’s joints. Ask whether the patient has ever had nerve conduction studies done. Enquire about symptoms of autonomic neuropathy, such as persistent postural dizziness, bloating, nocturnal diarrhoea, impotence and incontinence.

neurological complications—ask about peripheral paraesthesias, painful peripheries, burns, neuropathic ulcers and Charcot’s joints. Ask whether the patient has ever had nerve conduction studies done. Enquire about symptoms of autonomic neuropathy, such as persistent postural dizziness, bloating, nocturnal diarrhoea, impotence and incontinence. nephropathy—ask whether the patient has any urinary symptoms, such as frequency, polyuria and nocturia. Has the patient observed peripheral oedema that would suggest early-stage renal failure? Enquire about any previous investigations, such as 24-hour urinary collection for proteinuria, and whether the patient is aware of their level of renal function.

nephropathy—ask whether the patient has any urinary symptoms, such as frequency, polyuria and nocturia. Has the patient observed peripheral oedema that would suggest early-stage renal failure? Enquire about any previous investigations, such as 24-hour urinary collection for proteinuria, and whether the patient is aware of their level of renal function.• other complications:

– infections/sepsis—ask about previous or current oral or vaginal candidiasis, impetigo, ulcers, abscesses, carbuncles, furuncles and recurrent urinary tract infections

– diabetic foot—the presence of painful callosities, corns or ulcers. Any anatomical foot deformities that predispose to foot injury should be enquired into. Ask whether the patient sees a podiatrist and, if so, how often.

The social and occupational impact of diabetes on the patient should be discussed in detail. Talk about impotence, if relevant to the patient. Social and marital issues associated with this condition should be dealt with in detail. Check for a family history of diabetes mellitus and obtain details thereof.

Exclude possible secondary causes for the diabetes, such as chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly, polycystic ovary syndrome and consumption of drugs such as corticosteroids, thiazides and the oral contraceptive pill (see box).

Causes of secondary diabetes mellitus

1. Medications—glucocorticoids, diazoxide, thiazides, oral contraceptive pill

2. Cushing’s disease

3. Acromegaly

4. Polycystic ovary syndrome

5. Pancreatic insufficiency (e.g. chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis)

6. Obesity

7. Gestation

8. Haemochromatosis

9. Ataxia telangiectasia

10. Glucagonoma/vipoma

Examination

1. Body habitus—particularly looking for obesity, endocrinopathic appearance suggesting Cushing’s syndrome (see box), polycystic ovary syndrome or acromegaly (see box), and evidence of recent weight loss or weight gain. Measure the waist circumference and calculate the body mass index (BMI). Patients who have had type 1 diabetes from an early age may have stunted growth.

2. Postural blood pressure and postural pulse (postural response is absent in autonomic neuropathy)

3. State of hydration, injection marks, amputations, impetigo, acanthosis nigricans

4. Eye examination—looking for cataract, visual acuity, diabetic retinopathy and oculomotor nerve palsy with pupillary sparing

5. Oral cavity—for hygiene, periodontal disease and candidiasis

6. Abdomen—for hepatomegaly associated with diabetic fatty liver

7. Peripheral neuropathy (motor and sensory) and diabetic amyotrophy (in the quadriceps femoris musculature)—the 10 g Semmes-Weinstein monofilament test, looking for peripheral neuropathy (assesses the foot at risk)

8. Cutaneous stigmata—such as diabetic dermopathy, necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum and lipodystrophy associated with frequent injections (particularly in patients with poor technique)

9. Presence or absence of all peripheral pulses

10. A detailed diabetic foot examination.

Clinical features of Cushing’s syndrome

• Weight gain leading to central obesity

• Moon facies

• Excessive sweating

• Telangiectasia, straie, increased skin fragility (easy bruising)

• Hyperpigmentation

• Proximal myopathy

• Hirsutism

• Buffalo hump

• Decreased libido, impotence, amenorrhoea

• Mood disturbances (euphoria, depression and delirium)

• Hypertension

• Diabetes

Clinical features of acromegaly

• Enlargement of the hands and feet

• Protrusion of eyebrows and jaw

• Arthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome

• Increased spacing between the teeth

• Macroglossia

• Compression of the optic chiasma leading to bitemporal hemianopia

• Diabetes mellitus

• Hypertension

• Increased palmar sweating and seborrhea of the face

Investigations

Investigations that should be performed in the diabetic patient include:

1. Blood sugar level (capillary or venous)

2. Glycosylated haemoglobin (Hb A1c) level

3. Serum fructosamine level (not a very reliable test)

4. Full blood count

5. Fasting serum lipid profile

6. Electrolyte profile and the renal function indices—looking for evidence of renal impairment

7. Spot urine specimen—for proteinuria and for albumin-to-creatinine ratio (a ratio of > 2.5 is considered significant). If urine is positive for protein, a 24-hour urine collection should be carried out, looking for microalbuminuria. An albumin excretion of 30–300 mg over 24 hours is defined as microalbuminuria and is predictive of early diabetic nephropathy. The positive tests should be repeated within 3 months, and if there is persistent microalbuminuria on two occasions the patient should be commenced on an ACE inhibitor.

8. ECG—for evidence of ischaemic heart disease

Management

Discussion of therapeutic options revolves around the diabetic diet, regular physical exercise, oral hypoglycaemic agents and their side effects, and insulin therapy. Objectives of diabetes management include: 1) adequate control of the blood sugar level (fasting levels to be maintained below 6.1 mmol/L and postprandial levels below 7.8 mmol/L) and the glycosylated haemoglobin level (should be maintained below 7% in most cases, based on the patient’s clinical status); 2) prevention of end-organ complications; and 3) control of other vascular risk factors.

1. Hypoglycaemic agents—If the diabetic diet and physical exercise fail to provide adequate glycaemic control in the patient with type 2 diabetes, consider commencing an oral hypoglycaemic agent. Commonly used agents are:

• biguanides—metformin is the most common and the first line of pharmacotherapy in type 2 diabetes. Act to enhance peripheral insulin sensitivity. Side effects of this class of drugs include diarrhoea, nausea, impaired vitamin B12 absorption and lactic acidosis, particularly in patients with hepatic or renal failure.

• sulfonylureas—act via stimulation of pancreatic insulin secretion. Side effects of this class of drugs include hypoglycaemia, weight gain, rash and, very rarely, bone marrow suppression and cholestasis. Sulfonylureas have been associated with an increased mortality rate in post myocardial infarction patients.

• thiazolidinediones—rosiglitazone and pioglitazone are the thiazolidinediones currently available. These agents act mainly by improving insulin sensitivity and preserving pancreatic beta cell function. These agents have beneficial effects on cardiovascular health and have been observed to be able to prevent in-stent restenosis. According to the guidelines these agents are considered third-line therapy in difficult-to-control diabetes and should be added to the regimen when glycaemic control is suboptimal on biguanides and sulfonylureas. First-generation agent troglitazone was associated with hepatotoxicity, but other agents of this class (e.g. rosiglitazone) are believed to be safe. Thiazolidinediones give good blood sugar control when used in combination with insulin, metformin or sulfonylureas, but have a tendency to cause weight gain. In heart failure patients these agents may contribute to an exacerbation of the condition and they also have a negative impact on bone density, contributing to osteoporosis. It is very important to avoid this agent in patients with heart failure. Peripheral oedema is another commonly observed side effect. Rosiglitazone can elevate LDL as well as HDL levels, while pioglitazone has a neutral effect on LDL levels and a beneficial effect on HDL levels.

• meglitinides—repaglinide is a short-acting agent that acts by stimulating pancreatic insulin secretion, but can cause weight gain and hypoglycaemia. This agent can be given in combination with metformin.

• alpha-glucosidase inhibitor agents such as acarbose act to inhibit the activity of intestinal glucosidase enzymes. Their side effect profile includes bloating, abdominal discomfort, diarrhoea and flatulence.

2. Insulin therapy—Type 2 diabetic patients whose glycaemic control is suboptimal on oral agents alone need therapy with insulin, as do all type 1 diabetics. Insulin therapy can be commenced as an outpatient at a dose of 0.25 units per kg (in an inpatient it can be commenced at up to 1 unit per kg) and the dose increased according to the blood sugar control achieved. Different centres have different protocols for insulin therapy, so it is best to know thoroughly the one used at your centre. A combination short- and long-acting insulin 30/70 units twice daily divided into a ratio of 2:1, before lunch and before dinner, is a good starting regimen for the patient with type 2 diabetes. Premixed rapid-acting insulin 25 units is another attractive option for the mature-onset diabetes patient. This is composed of 25% insulin lispro (rapid-acting) with 75% insulin lispro-protamine (intermediate-acting), and should be administered preprandially twice daily. Because of its very rapid onset of action, it can be given immediately before meals, thus ensuring convenience of use and better compliance. Insulin regimens for the patient with type 1 diabetes are different from those for the patient with type 2 diabetes and are usually a four-times-a-day regimen.

Once-daily, long-acting insulin analogues such as glargine can be given to patients with type 2 diabetes on oral agents requiring insulin therapy.

3. Education—This is often overlooked in the management of diabetes. Patient education should be discussed in detail and should take the following format:

• Educate the patient on the need to control blood sugar levels adequately, to prevent end-organ damage, and warn about the severe adverse consequences of poor control. Teach them how to monitor blood sugar levels, giving instructions on the methods and frequency. Initially it is wise to monitor the blood sugar level several times daily at regular intervals. This can be done immediately before each meal and 2 hours postprandially. Once stable levels are achieved, twice-daily monitoring is adequate—this should be done at different times on different days, so that a good estimate of the overall control can be gained. A satisfactory level at which to maintain blood sugar is 4–8 mmol/L.

• Advise on the optimal diabetic diet and the benefits of regular, light physical exercise. Diet should comprise at least 50% carbohydrate, made up of food with a low glycaemic index and containing complex carbohydrates. Food should contain minimum amounts of saturated fat. A high fibre content and mono- or polyunsaturated fats are highly desirable. The patient should take smaller portions at regular intervals (three main meals and one snack between each meal) to maintain blood sugar levels at a uniform range and avoid rapid fluctuations.

4. Prevention of end-organ damage—When a patient tests positive for microalbuminuria it is important to ensure strict blood pressure control to prevent progression to diabetic nephropathy. Ideally the blood pressure in the diabetic patient will be below 130/85 mmHg. All nephrotoxic drugs should be stopped and care should be exercised when administering ionic radiocontrast material to the patient. To prevent atherosclerotic vascular disease, the patient should be strongly advised against smoking, and strict control of serum cholesterol levels should be ensured (aim at LDL < 2.0 mmol/L). Global risk factor modification also involves strict control of blood pressure too.

5. Weight reduction—Should be promoted if the patient is overweight or obese. Losing 5–10 kg is of significant benefit. This can be achieved by joule restriction and regular exercise. A suitable form of exercise is brisk walking for at least 30 minutes a day, 4 days a week. Resistant cases may benefit from agents such as orlistat, which is an inhibitor of gastrointestinal lipase. Warn the patient about the side effects of greasy stool, frequency of defecation and bulky stool.

6. Family education and support—Do not forget to stress the importance of providing education and support to the patient’s family. Diabetes is best managed in a multidisciplinary setting with the participation of the physician, general practitioner, nurse educator, podiatrist, nutritionist and social worker.

7. In some jurisdictions the local department in charge of roads and traffic may require notification of a person’s diagnosis with diabetes.

Cholesterol target guidelines

Cholesterol-lowering drug therapy is indicated for any patient with a diagnosis of coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes with either age > 60 years or microalbuminuria or Aboriginal ethnicity or a significant family history of coronary heart disease at a younger age. These patients do not need a lipid level done prior to commencement of therapy.

OBESITY

Case vignette

A 45-year-old obese female is admitted after a suicide attempt with ingestion of and overdose of tricyclic antidepressant. She has recovered from the acute episode but complains of early morning headache of long-standing duration, exertional dyspnoea, bilateral knee pain on walking, lower back pain, cold intolerance and easy bruising. She has known diabetes mellitus managed on metformin and rosiglitazone. On examination she is obese with a BMI of 35. She is tachycardic at 100 bpm and hypertensive at 140/95 mmHg and there is a loud P2 in the precordium. There is evidence of hirsutism, acanthosis nigricans and bipedal oedema.

1. What other clinical information is required to consider the most likely differential diagnosis?

2. What are the possible contributing factors to her obesity?

3. What investigations would you request?

4. What are the psychosocial issues related to her obesity and how do you propose to manage these?

5. Suggest a treatment plan for this patient.

Approach to the patient

Obesity may be central to many a medical problem that a long case patient presents with. It may be an incidental observation, but obesity needs addressing if present. Obesity is associated with an increased all-cause mortality and in particular cardiovascular mortality. A BMI of > 30 is defined as obesity according to the US National Institute of Health criteria. A BMI of 19–25 is considered healthy and desirable.

History

Ask about:

• family history of obesity

• age of onset of obesity

• any recent weight gain

• vascular risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and smoking

• symptoms such as excessive sweating, headache, visual disturbance (bitemporal hemianopia), easy bruising and cold intolerance—may suggest endocrinological disorders known to cause obesity, such as Cushing’s syndrome, myxoedema or pituitary tumour

• medications that contribute to weight gain, such as corticosteroids, insulin and rosiglitazone

• snoring (bed partner’s report)

• daytime somnolence

• early-morning diuresis and waking in the morning not feeling fresh—may suggest obstructive sleep apnoea (common in the obese)

• medications that would cause weight gain, such as sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones

• detailed dietary history—this is very important, with information about the types of food consumed and the frequency of meals. Ask whether the patient is on a particular diet (in particular enquire about popular diets) and if so, ask about the benefits and side effects experienced.

• details of the occupational and social problems associated with obesity

• previous attempts at weight loss and reasons for failure.

Estimate the level of insight the patient has into his or her condition.

Examination

Calculate the BMI and the waist-to-hip ratio. Check the exact distribution of fat. Check blood pressure. Look for features of any associated endocrinological disorder, such as

cushingoid body habitus, easy bruising and buffalo hump (suggestive of Cushing’s syndrome), peach complexion, goitre and bradycardia (suggestive of myxoedema), and

virilisation in a female patient (suggestive of polycystic ovary syndrome).

Investigations

1. Random or fasting blood sugar level—looking for hyperglycaemia

2. Fasting lipid profile—looking for hyperlipidaemia

3. Liver function tests—looking for abnormalities that may be due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

4. Thyroid function tests—looking for hypothyroidism

5. 24-hour urinary cortisol excretion—to screen for Cushing’s syndrome.

The major predictor of health risks associated with primary obesity is body fat distribution. Android distribution or central obesity (adiposity preferentially located in the abdomen) is associated with a variety of metabolic derangements, including dyslipidaemia, hypertension and glucose intolerance. Obesity is also associated with type 2 diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, stroke, gallbladder disease, liver function abnormalities due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and osteoarthritis of the weight-bearing joints (see box).

Morbidities associated with obesity

• Coronary artery disease

• Atrial fibrillation

• Congestive cardiac failure/right heart failure (cor pulmonale)

• Stroke

• Deep venous thrombosis

• Hypertension

• Hyperinsulinaemia

• Diabetes mellitus

• Obstructive sleep apnoea

• Restrictive lung disease

• Hypoventilation

• Reflux

• Hirsutism

• Acanthosis nigricans

• Gout

• Osteoarthritis

• Cancer

• Depression

Management

1. Educate the patient about the ills of obesity and the need for significant weight loss.

2. Formulate a practical weight-loss program with definite goals and a timetable.

3. Prescribe a low-joule/high-fibre diet in consultation with a dietitian. Educate the patient about joule counting and fat counting. Encourage the patient to eat only small portions of food.

4. Encourage regular physical exercise. Light exercise to the level of slight breathlessness for 20–30 minutes, four times a week, would be adequate. This may take the form of fast walking, jogging or swimming.

5. For refractory patients, prescription of anti-obesity medications such as orlistat may be beneficial. But when prescribing a lipase inhibitor such as orlistat, warn the patient about the side effects of faecal urgency, greasy stool, increased frequency of defecation and, at times, faecal incontinence.

6. Other pharmacotherapeutic agents include phentermine and sibutramine (Reductil®).

7. Bariatric surgery should be considered for morbidly obese patients who respond poorly to non-surgical measures.

8. Rimonabant is a new cannabinoid receptor antagonist that has shown promise as an antiobesity and smoking cessation agent. However, it should not be used in the setting of depression.

CORTICOSTEROID USE

Case vignette

A 74-year-old woman presents with recent weight gain, occasional blurred vision and polyuria. She has been commenced on prednisolone 25 mg daily for a recent diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. On examination she has cutaneous striae and evidence of easy bruising together with abdominal obesity and a moon facies.

Approach to the patient

History

When assessing patients commenced or maintained on long-term corticosteroid therapy, it is important to find out whether the patient is aware of the multiple adverse effects associated with such therapy and the precautionary measures that need to be taken to minimise such effects. If the patient has been on steroids for a considerable period of time, ask about weight gain, easy bruising, insomnia, polyphagia, ankle oedema, irritability and the psychological symptoms of depression or psychosis. Ask whether the patient has ever been tested for diabetes and, if so, how often and using which test. Also ask whether the patient’s blood pressure is monitored closely. Ask whether the patient has had cataracts diagnosed or experienced any visual impairment. Some patients may develop glaucoma associated with steroid use.

Corticosteroids at a dose higher than the replacement dose (equivalent of 7.5 mg per day of prednisolone) for more than 6 months can predispose the patient to osteoporosis, and it is important to enquire whether the patient has ever been diagnosed with osteoporosis and, if so, what treatment he or she has received. If not, ask whether they have ever had bone densitometry done. Ask about any fractures on minimum impact, and bone pain, and whether a radioisotope bone scan has been performed. Patients on corticosteroids benefit from calcium and vitamin D supplementation (steroids can impair vitamin D absorption in the gut) in addition to bisphosphonates and hormone replacement therapy in the setting of established osteoporosis. Ask about hip pain on movement, a feature that may suggest aseptic necrosis of the femoral head. Ask about infections, particularly atypical infections such as Pneumocystis carinii, cytomegalovirus infections, tuberculosis, Cryptococcus neoformans and recurrent oral and genital candidiasis.

Examination

Look for moon-shaped facies, cushingoid body habitus, multiple cutaneous ecchymoses, evidence of skin fragility, cataract, oral candidiasis, buffalo hump, proximal muscle loss and weakness, tenderness in the hip joints and tenderness in the vertebral column (see box).

Adverse effects of chronic corticosteroid therapy

• Obesity

• Cushingoid body habitus

• Hypertension

• Diabetes mellitus

• Hirsutism

• Cutaneous fragility/striae

• Acne

• Immunosuppression/opportunistic infection

• Oral/vaginal candidiasis

• Cataract

• Osteoporosis

• Proximal myopathy

• Avascular necrosis of bone (especially head of femur)

• Mood disorders/psychosis

• Peptic ulcer disease

• Pancreatitis

• Hypokalaemia

• Peripheral oedema

• Suppression of hypothalamic–pituitary axis

It is highly recommended that these patients be regularly vaccinated with pneumococcal vaccine every 5 years and influenza vaccine every year.

Ask about any steroid-sparing agents that have been tried, and their effects.

OSTEOPOROSIS

Approach to the patient

History

Ask about back pain, any falls or fractures and the treatment received. Check whether the patient is on any therapeutic agents that would contribute to osteoporosis. Ask about family history of osteoporosis and enquire into the menopausal status. Postmenopausal osteoporosis is common, but do not forget other contributing factors relevant to the patient’s circumstances, such as chronic corticosteroid use, chronic renal failure, vitamin D deficiency, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, multiple myeloma and Cushing’s syndrome.

Examination

Look for bone tenderness, vertebral column abnormalities and exclude physical signs of endocrine disorders such as Cushing’s syndrome.

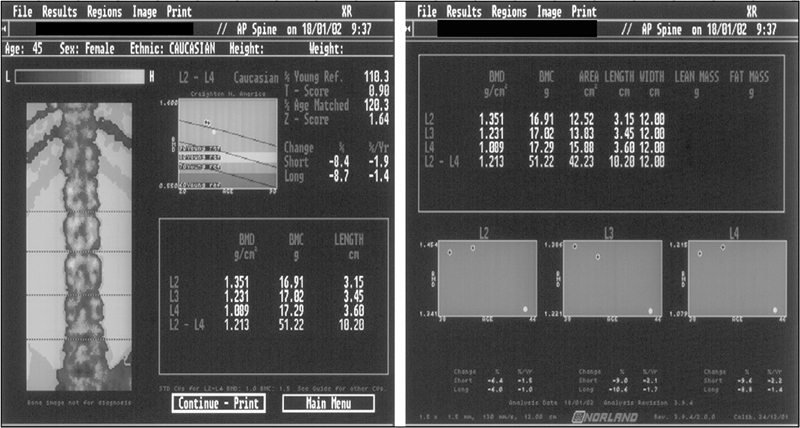

Osteoporosis is common and the cause can be multifactorial. If clinical assessment suggests the existence of osteoporosis in the patient, ask the examiner for the report of the dual-energy X-ray densitometry (DEXA) study to establish a definite diagnosis. Candidates should be able to quickly and accurately interpret the Z and T scores in the bone densitometry report (Fig 9.1). A bone mineral density value lower than 1 standard deviation below the mean bone densitometry value of the young normal (T score < 1) should be considered an indication for the initiation of preventive measures. A T score of –2.5 or below is considered diagnostic of osteoporosis and an indication for treatment. A significantly abnormal Z score should alert the candidate to secondary causes of osteoporosis. Remember, most pathological fractures due to osteoporosis occur in the mid- and lower thoracic and upper lumbar regions of the vertebral column. Pathological fractures elsewhere in the vertebral column should arouse suspicion of other causes, such as malignancy.

Investigations

1. Bone densitometry

2. Serum testosterone levels in male patients, to exclude hypogonadism

3. Thyroid function tests

4. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and serum calcium and phosphate levels

5. Renal function indices—to exclude chronic renal failure

6. Serum electrophoresis and immunoelectrophoresis—to exclude multiple myeloma

7. 24-hour urinary cortisol levels—to exclude Cushing’s syndrome

Management

1. Correct the underlying cause, if there is one—this is the first step in the management of osteoporosis.

2. Education—educate and encourage the patient to adopt lifestyle measures that will prevent the progression of osteoporosis, such as ingestion of food with high calcium content, calcium supplements, adequate amounts of vitamin D, regular low-impact and weight-bearing physical exercise, cessation of smoking and reduction of alcohol intake. Postmenopausal women should aim at ingesting 1.5 g of calcium daily.

3. Pharmacology—pharmacological treatment of osteoporosis is a judicious decision that needs to be taken on further consideration of the patient’s clinical condition. If the bone mineral density is significantly low, or the patient is older, or if there is an established pathological fracture, the need for pharmacological intervention is significantly high, and hence can be justified:

• Bisphosphonate therapy is of proven benefit in osteoporosis. The oral agents alendronate, etidronate and risedronate are useful in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. They have been shown to decrease the rate of new fractures occurring in the vertebrae and hips. These agents, however, can cause severe oesophagitis. To prevent this adverse effect, the patient should be advised to take the drug first thing in the morning with a glass of water, at least 30 minutes before breakfast. The patient should also avoid lying down for at least 30 minutes after the ingestion of the drug. For patients intolerant of oral forms, once-a-month IV pamidronate infusion is a suitable alternative.

• Other agents that should be considered include raloxifene, the selective oestrogen receptor modulator (SERM) and calcitriol (vitamin D). Calcium supplements should be recommended for all osteoporosis patients. Venous thromboembolism is a serious side effect of raloxifene.

Intermittent dosing of recombinant human parathyroid hormone (teriparatide) has been shown to benefit postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis. Anabolic steroids too have been shown to be beneficial in this group of patients.

Strontium ranelate is approved for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis and has been shown to reduce vertebral and hip fractures.

Often a combination of different agents based on the clinical scenario is necessary to optimise the management of osteoporosis.

PAGET’S DISEASE

Approach to the patient

Paget’s disease is encountered in the long case patient, but often as an inactive disease condition. Usually the active disease presents with bone pain, deformity and pathological fracture.

History

Ask when and how the diagnosis was made and what treatment has been received so far. Ask about any change in hat size (though not many people wear hats these days!) or the size of spectacle frames, bone deformity, joint pain and symptoms of cardiac failure. By now you may have noticed whether the patient has any hearing impairment, which may be due to Paget’s disease of the ear ossicles or compression of the acoustic nerve. Check whether the patient suffers from ureteric colic.

Examination

Observe skull enlargement (skull diameter > 55 cm is abnormal), back deformity and limb deformity. Note lateral bowing of the femur and anterior bowing of the tibia. A bony mass lesion in the lower limb should alert the candidate to osteosarcoma. Auscultate for bruits in the skull and other bones. Look for osteoarthritis, particularly in the knees. Perform a detailed cardiovascular examination, looking for evidence of high-output cardiac failure. Conduct a detailed neurological examination, looking for deficit due to compression of cranial nerves at the cranial foramina and of brainstem due to platybasia. Look in the fundi for angioid streaks and optic atrophy.

Investigations

If there is an index of suspicion or a clinical indication, ask for confirmatory tests for Paget’s disease, which include:

1. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels— > 600 mmol/L is considered highly suggestive

2. Urinary deoxypyridinoline and N-telopeptide levels—levels of these markers also reflect disease activity

3. Skeletal X-rays of the relevant regions—when sclerotic bony lesions are seen, differential diagnoses that should also be considered are carcinoma of the prostate in the male and carcinoma of breast in the female

4. Three-phase bone scan—to exclude fractures and the complication of osteosarcoma.

Management

Symptomatic treatment is with analgesics, paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Disease-specific pharmacological treatment is indicated only if there is pain or active disease near a major joint or in a long bone.

The mainstay of treatment is oral bisphosphonates in the form of alendronate, tiludronate, risedronate or IV pamidronate. Calcitonin is used only rarely these days. Treatment should be continued until disease activity ceases, as indicated by symptoms and biochemical markers.

HYPERTHYROIDISM

Case vignette

A 61-year-old man presents with acute dyspnoea, delirium and high fevers after a CT coronary angiogram. He is agitated and has diarrhoea. On examination his blood pressure is 130/85 mmHg and pulse is 120 bpm and irregularly regular. He has diffuse crepitations in the lower zones of both lungs and pitting bipedal oedema. In the background history it is revealed that he has been investigated by his general practitioner for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, heat intolerance and recent weight loss.

1. What are the possible differential diagnoses in this case and what investigations would you request?

2. He has a palpable nodule in the thyroid region and the thyroid function tests reveal elevated T3 levels and significantly suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels. What is the most likely reason for his clinical picture?

3. What is your acute management plan?

4. Develop a comprehensive long-term and definitive plan of management for this man upon his recovery from the acute crisis.

Approach to the patient

The patient’s age may give some clues to the aetiology. Younger patients are more likely to get hyperthyroidism from Graves’ disease and older patients from toxic adenomata or toxic nodular goitres.

History

Ask about:

• visual impairment and headache—may be clues to a pituitary adenoma secreting TSH, although this is very rare

• recent fevers (viral illness) and tenderness over the thyroid gland—suggestive of acute or subacute thyroiditis as a possible differential diagnosis

• whether the patient has had recent iodine-containing contrast dose (coronary angiography etc)—would suggest the possibility of iodine-induced hyperthyroidism

• symptoms such as anxiety, excessive sweating, tearfulness and palpitations

• how the patient handles heat—heat intolerance is a salient feature

• significant weight loss in spite of an increased appetite

• sexual function—loss of libido and impotence in the male can be associated with hyperthyroidism

• menstrual period in females—menstrual abnormalities are common with this condition

• weakness—elderly patients with clinical hyperthyroidism may manifest only weakness and this phenomenon is called apathetic thyrotoxicosis

• whether the patient has ever been treated with amiodarone and whether they have had radiation exposure, particularly to the neck area—remember that the most common cause of hyperthyroidism is Graves’ disease.

Examination

Look for warm, clammy skin and evidence of wasting/weight loss. Check the pulse for AF or tachycardia. Perform an eye examination, looking for lid retraction and lid lag. Patients with cardiac involvement may show evidence of heart failure. Perform a detailed neck examination, looking for a goitre and also lymphadenopathy. If a goitre is found, define the features in detail, including the size, consistency, tenderness and nodularity. Check the limbs for muscle weakness due to thyroid myopathy. Neurological examination shows brisk reflexes and a fine tremor of the upper extremities. Male patients may have gynaecomastia. Look in the extremities for clubbing-like thyroid acropachy and the nail bed for onycholysis. Patients with Graves’ disease may have the eye signs of exophthalmos, conjunctival oedema and periorbital oedema. They may also have skin infiltration manifesting as pretibial myxoedema.

Investigations

1. Serum TSH and free T4/T3 levels—usually TSH is suppressed due to T4/T3 elevation in primary hyperthyroidism. Elevated levels of TSH and T4 are seen with amiodarone therapy. Elevated TSH may indicate secondary (pituitary) hyperthyroidism, which is extremely rare.

3. Radioactive iodine uptake thyroid scan—increased activity is indicative of Graves’ disease, toxic adenoma or toxic nodular goitre, whereas decreased uptake is suggestive of inflammation (thyroiditis).

4. If clinical features suggest and serum TSH is normal or elevated, a cranial CT or MRI—to exclude pituitary tumour.

5. ECG looking for AF, and echocardiogram to assess left ventricular function.

Management

1. Symptomatic treatment with a beta-blocker

2. Carbimazole or propylthiouracil—to achieve euthyroid state. Iodine therapy alone at high doses or in combination with carbimazole can also help achieve euthyroid state.

3. Radioactive iodine—for ablation of the hyperactive thyroid gland

4. Surgery—if relevant for large goitres

HORMONE REPLACEMENT THERAPY

Many patients in the long case examination may be on hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The question of continuation of this therapy may be a subject of interest in the discussion. HRT has proven benefits in the prevention and management of senile osteoporosis. There is observational evidence to support the usefulness of HRT in lowering LDL and lipoprotein-a and in elevating HDL levels, and therefore would seem to have a cardiovascular benefit. However, recently completed controlled trials have failed to demonstrate any objective benefits of HRT in improving the clinical end-points of cardiovascular disease. It has further demonstrated that HRT can increase the incidence of DVT and thromboembolism in some treated patients. Anecdotal risks of malignancies, too, should be acknowledged.

Raloxifene is a selective oestrogen receptor modulator that has shown promise as an alternative to conventional HRT. It acts as an oestrogen receptor agonist in the skeletal tissue and the cardiovascular system, and as an oestrogen receptor antagonist in the breast and the uterus. It is not very useful in the management of perimenopausal symptoms. The incidence of DVT with its use is similar to that of conventional hormonal therapy. The other distressing side effect of this agent is persistent cramps in the legs. Its main indication is for the prevention and treatment of senile osteoporosis. There are observational data supporting its beneficial effect on the serum lipid profile, but end-point data are still awaited. It has also been shown to be helpful in decreasing the incidence of breast cancer. The above information should help the clinician in making a decision regarding the continuation of HRT and deciding on an alternative if indicated.