16 Endocrine disorders

The history

Presenting symptoms

There are a number of symptom complexes that particularly suggest endocrine disease.

Thirst and polyuria

Excessive thirst (polydipsia) and increased urine output (polyuria) are the most important presenting symptoms of diabetes mellitus; these are discussed in detail in Chapter 17. Polydipsia and polyuria may also be due to impairment of renal concentrating capacity as a result of a deficiency of antidiuretic hormone (cranial diabetes insipidus) or a failure of antidiuretic hormone action (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus). The latter may be inherited or may occur secondary to impairment of antidiuretic hormone action by hypercalcaemia or hypokalaemia. Sometimes, apparent polydipsia and polyuria may be due to increased fluid intake, which at its most extreme may be vastly excessive (psychogenic polydipsia). The distinction between psychogenic polydipsia and diabetes insipidus is important. Generally, nocturnal polyuria is not a feature of psychogenic polydipsia, but this is not an absolute distinction and further investigation of urine concentrating capacity is usually required.

Weight loss

Loss of weight is a feature of decreased food intake or increased metabolic rate. Sometimes both factors may operate to reduce body weight, as in the cachexia of malignant disease. Thyroid overactivity (hyperthyroidism) is nearly always associated with a combination of weight loss and increased appetite, although occasionally the latter may be stimulated more than the former so that there is a paradoxical increase in weight. Weight loss is rarely the sole presenting symptom of hyperthyroidism and other clinical features often predominate, particularly in younger patients (Box 16.1). In the elderly, however, hyperthyroidism may be occult or may simulate the gradual weight loss of malignant disease. Cardiac arrhythmias are a frequent feature in the elderly. Anorexia nervosa, a psychogenic disorder characterized by a long history of low body weight in the absence of other features of ill health, must be considered, especially in young women. Any form of weight loss may be associated with amenorrhoea.

Other endocrine conditions in which weight loss is a major feature are listed in Box 16.2. Weight loss associated with diabetes mellitus is discussed in Chapter 17.

Weight gain or redistribution

An increase in body weight (Box 16.3) is a predictable result of a reduction in metabolic rate. Weight gain is therefore a common feature of primary hypothyroidism. However, obesity is rarely a consequence of specific endocrine dysfunction, an exception being the recently described but very rare phenomenon of leptin deficiency. In the majority of patients, ‘simple obesity’ is due to a longstanding imbalance between energy intake and expenditure; it frequently begins in childhood and is often present in more than one family member. Glucocorticoid hormone excess (Cushing’s syndrome) results in an increase in body fat predominantly involving abdominal, omental and interscapular fat (truncal obesity), with paradoxical thinning of the limbs due to muscle atrophy.

Muscle weakness

Symptomatic muscular weakness not due to neurological disease is a feature of several metabolic disorders, including thyrotoxicosis, Cushing’s syndrome and vitamin D deficiency. In all these conditions, the metabolic myopathy (Box 16.4) causes symmetrical proximal weakness, mainly involving the shoulder and hip girdle musculature. There is usually associated muscle wasting. The major symptom is difficulty in climbing stairs, boarding a bus or rising from a sitting position. Most patients with hyperthyroidism have proximal weakness. This may be subclinical; it is best demonstrated by asking the patient to rise from the squatting position. The proximal myopathy of vitamin D deficiency is often painful, in contrast to other causes. The differential diagnosis of painful proximal muscular weakness includes polymyositis and polymyalgia rheumatica, as well as spinal root or plexus disease.

Cold intolerance

An abnormal sensation of cold, out of proportion to that experienced by other individuals, may indicate underlying hypothyroidism (Boxes 16.5 and 16.6). This symptom differs from the localized vasomotor symptoms in the hands found in Raynaud’s phenomenon and is rather non-specific, especially in the elderly.

Fasting symptoms

Autonomous insulin production due to an insulinoma.

Autonomous insulin production due to an insulinoma.

Glucocorticoid deficiency, with or without thyroxine and growth hormone deficiency (e.g. primary adrenal failure or hypopituitarism).

Glucocorticoid deficiency, with or without thyroxine and growth hormone deficiency (e.g. primary adrenal failure or hypopituitarism).

Inappropriate insulin or excessive sulphonylurea drug administration in a diabetic patient.

Inappropriate insulin or excessive sulphonylurea drug administration in a diabetic patient.

Rarer causes of hypoglycaemia, for example hepatic failure and rapidly growing malignant lesions, especially thoracic or retroperitoneal mesothelial tumours secreting proinsulin-like growth factor II.

Rarer causes of hypoglycaemia, for example hepatic failure and rapidly growing malignant lesions, especially thoracic or retroperitoneal mesothelial tumours secreting proinsulin-like growth factor II.

Cramps and ‘pins and needles’

Intermittent cramp and ‘pins and needles’ (paraesthesiae), especially if bilateral, can be due to a decreased level of circulating ionized calcium. This may occur in hypoparathyroidism or be associated with a fall in the ionized component of serum calcium, owing to an increased extracellular pH (alkalosis). The latter may occur with any alkalosis, but is particularly well recognized in hyperventilatory states (respiratory alkalosis) and hypokalaemia (metabolic alkalosis). Refractory cramping symptoms after correction of hypocalcaemia can be due to an associated hypomagnesaemia. However, the differential diagnosis of paraesthesiae in the hands includes median nerve compression at the wrist (carpal tunnel syndrome), a syndrome that is usually accompanied by typical sensory and motor disturbance suggestive of a lesion in the median nerve (see Ch. 14).

Impotence

Reduced erectile potency may be a consequence of primary abnormalities, such as the following:

Galactorrhoea

Prolactin-secreting tumours of the pituitary gland.

Prolactin-secreting tumours of the pituitary gland.

Idiopathic galactorrhoea, in which there is an apparent increased sensitivity to normal levels of serum prolactin.

Idiopathic galactorrhoea, in which there is an apparent increased sensitivity to normal levels of serum prolactin.

Hyperprolactinaemia due to hypothyroidism.

Hyperprolactinaemia due to hypothyroidism.

Hyperprolactinaemia due to dopamine antagonist drugs.

Hyperprolactinaemia due to dopamine antagonist drugs.

Hyperprolactinaemia due to lactotroph disinhibiting lesions of the hypothalamopituitary region.

Hyperprolactinaemia due to lactotroph disinhibiting lesions of the hypothalamopituitary region.

The examination

General assessment

This should begin with observing the general appearance of the patient. Start by assessing the state of nutrition and by measuring weight and height. Calculate the body mass index (BMI). The distribution of fat should be noted. Deposition of fat in the intra-abdominal, thyrocervical and interscapular regions with relative sparing of the limbs (truncal obesity) is characteristic of Cushing’s syndrome and is accompanied by a typical moon-faced plethoric appearance (Fig. 16.1) owing to a combination of increased subcutaneous fat and thinning of the skin.

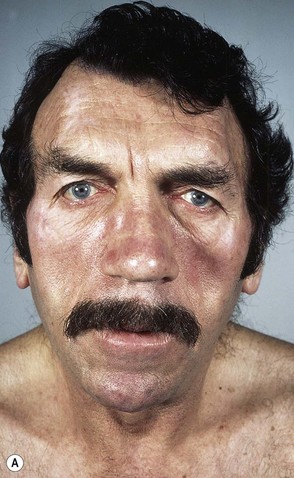

Patients with growth hormone hypersecretion, resulting from somatotroph pituitary adenomas, also demonstrate a classic facial appearance with increased fullness and coarsening of soft tissues, including the lips and tongue which, in patients with longstanding disease, may be accompanied by overgrowth of the zygoma, orbital ridges and mandible (prognathism) (Fig. 16.2). Acromegaly in young people occurring before epiphyseal fusion causes abnormally tall stature (gigantism). Increased adiposity in a child who is growing poorly suggests the possibility of growth hormone deficiency, hypothyroidism or, rarely, Cushing’s syndrome. Simple obesity is associated with normal or increased linear growth velocity.

A unique selective shortening of the fourth and fifth metacarpals may be found as the major somatic manifestation of a group of recessively inherited disorders of parathormone action (pseudohypoparathyroidism; Fig. 16.3).

The skin

Pigmentation, especially buccal, circumoral or palmar, may indicate the increased secretion of ACTH that occurs with adrenal failure (Addison’s disease; Fig. 16.4); patches of depigmentation, or vitiligo (Fig. 16.5), may also be found in Addison’s disease or other organ-specific autoimmune disorders. Violaceous striae, arising as a result of stretching of thin skin with exposure of the dermal capillary circulation, suggest the possibility of glucocorticoid excess (Fig. 16.6), and abnormal dryness of the skin and coarseness of the hair are found in hypothyroidism (Fig. 16.7). Localized thickening of the dermis due to mucopolysaccharide and inflammatory cell deposition, particularly on the anterior aspects of the legs when it is known as pretibial myxoedema, is one of the classic but relatively rare extrathyroidal manifestations of Graves’ disease.

Figure 16.5 Extensive areas of depigmentation (vitiligo) in a patient with organ-specific autoimmune disease.

The thyroid

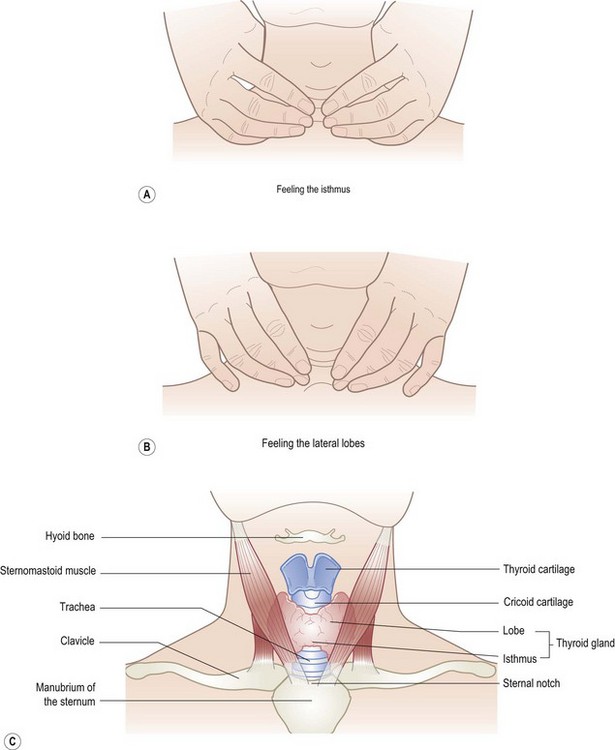

The anatomical landmarks relevant to inspection and palpation of the thyroid are shown in Figure 16.8. Immediately inferior to the thyroid cartilage (with its superior notch) is the cricoid cartilage, with the thyroid isthmus lying just below in the midline. The right and left lobes of the thyroid curve posterolaterally round the trachea and oesophagus and are partially covered by the sternomastoid muscles. The attachment of the thyroid to the pretracheal fascia dictates that it moves superiorly on swallowing; absence of this movement raises the possibility of an infiltrative thyroid carcinoma. Remember that the right lobe is slightly larger than the left; hence, diffuse thyroid enlargement, as in Graves’ disease, is often apparently asymmetrical. There are several methods for examining the thyroid, but a suggested routine is as follows.

Thyroid palpation is best carried out from behind, with the patient’s neck slightly extended, but not so much that the neck musculature is tightened. This may feel awkward initially, but with time and practice it will become more comfortable. Have a glass of water available throughout the examination, so the patient may take repeated sips and swallow as necessary. Position both hands to encircle the neck (Fig. 16.8A), with the fingers slightly flexed, such that the tips of the index fingers lie just below the cricoid in order to palpate the isthmus. Now rotate the fingers down and slightly laterally in order to feel the lateral lobes, including the inferior border (Fig. 16.8B). The anterior surface of each lobe should be no larger than the terminal phalanx of the patient’s thumb.

The following points should be addressed:

Is the thyroid diffusely enlarged, as in thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)-mediated or autoimmune enlargement (Fig. 16.8D)? If so, is it soft (e.g. dyshormogenesis, diffuse goitre of puberty) or firm/hard (e.g. autoimmune thyroiditis). In general, the firmer the texture of an enlarged thyroid, the more likely is the pathology to be autoimmune.

Is the thyroid diffusely enlarged, as in thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)-mediated or autoimmune enlargement (Fig. 16.8D)? If so, is it soft (e.g. dyshormogenesis, diffuse goitre of puberty) or firm/hard (e.g. autoimmune thyroiditis). In general, the firmer the texture of an enlarged thyroid, the more likely is the pathology to be autoimmune.

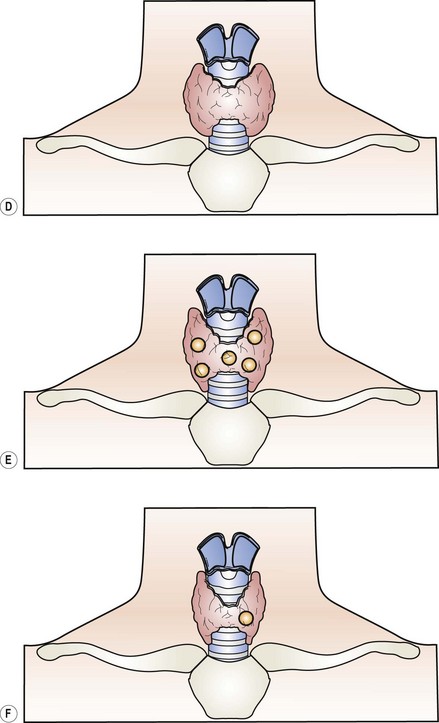

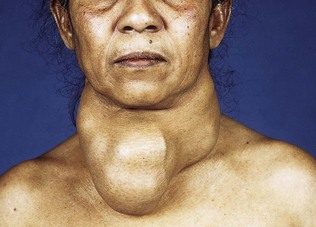

Are there two or more identifiable nodules (Fig. 16.8E, Fig. 16.9) and, if so, is the patient thyrotoxic and does the gland extend downward behind the sternum? (If the gland is partially or completely retrosternal, the inferior border may not be palpable, or palpable only on swallowing.) Most multinodular goitres are benign, but a history of neck irradiation, enlarged cervical lymph nodes or progressive enlargement of one of the nodules raises the suspicion of malignancy.

Are there two or more identifiable nodules (Fig. 16.8E, Fig. 16.9) and, if so, is the patient thyrotoxic and does the gland extend downward behind the sternum? (If the gland is partially or completely retrosternal, the inferior border may not be palpable, or palpable only on swallowing.) Most multinodular goitres are benign, but a history of neck irradiation, enlarged cervical lymph nodes or progressive enlargement of one of the nodules raises the suspicion of malignancy.

Is the palpable abnormality a single focal nodule (Fig. 16.8F), suggesting a cyst, adenoma or carcinoma? Rapid growth, hard texture, lack of movement on swallowing (see above), enlarged regional lymphadenopathy, male gender and a history of neck irradiation all increase the probability of malignancy.

Is the palpable abnormality a single focal nodule (Fig. 16.8F), suggesting a cyst, adenoma or carcinoma? Rapid growth, hard texture, lack of movement on swallowing (see above), enlarged regional lymphadenopathy, male gender and a history of neck irradiation all increase the probability of malignancy.

Is the goitre firm and asymmetrical?

Is the goitre firm and asymmetrical?

Are there features of local pressure effects or local infiltration (e.g. dysphonia from recurrent laryngeal involvement)?

Are there features of local pressure effects or local infiltration (e.g. dysphonia from recurrent laryngeal involvement)?

Is there weight loss and debility? These suggest anaplastic carcinoma or lymphoma.

Is there weight loss and debility? These suggest anaplastic carcinoma or lymphoma.

Is there a bruit, indicating increased blood supply? This is frequently found in untreated Graves’ disease, but should not be confused with a transmitted bruit from the carotid.

Is there a bruit, indicating increased blood supply? This is frequently found in untreated Graves’ disease, but should not be confused with a transmitted bruit from the carotid.

The breasts and genitalia

The breasts should be examined for mass lesions and, if suggested by the history, for galactorrhoea. In the adolescent female, physiological breast enlargement provides a precise index of pubertal status and signals the onset of the pubertal growth spurt (Tanner stage 3 breast development). Onset of menses (menarche) is a relatively late pubertal event at which point pubertal breast development is virtually complete. In males, any tendency to gynaecomastia should be noted (Fig. 16.10). This may range from minor degrees of subareolar glandular enlargement to substantial breast prominence; breast enlargement associated with generalized adiposity should not be confused with true gynaecomastia.

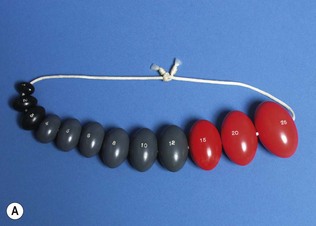

Genital examination in the male should document testicular volume. This is particularly important in the assessment of pubertal development, for which volume should be measured by comparison with calibrated ovoids (Prader orchidometer; Fig. 16.11). Prepubertal testicular volume is less than 4 ml; increased volume implies pubertal gonadotrophin stimulation. Onset of the pubertal growth spurt in boys is associated with a testicular volume of 10 ml and normal adult testicular volume is in the range of 15 to 25 ml. In the assessment of normal puberty, it is important to establish that growth velocity and gonadal changes (testicular volume or breast stage) are concordant, since a discordance of puberty proceeding ahead of growth implies an abnormal source of sex steroid (e.g. androgen-secreting tumours or congenital adrenal hyperplasia). Testicular atrophy in the adult male indicates hypogonadism, due either to primary testicular failure, hypothalamopituitary dysfunction or chronic liver disease. Tumours of Leydig cells are usually palpable and should be sought in any patient with gynaecomastia.

The eyes

The hypercalcaemic patient should be carefully examined for corneal calcification, evident as a narrow band on the medial or lateral border of the cornea (Fig. 16.12); this usually indicates longstanding hypercalcaemia and a diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism.

Figure 16.12 Corneal calcification (band keratopathy) in a patient with longstanding hyperparathyroidism.

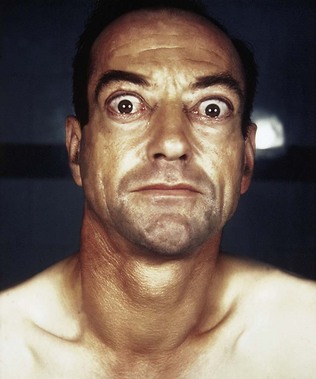

In patients with thyroid disease, the presence of exophthalmos (proptosis) should be noted. This may be unilateral or bilateral, and may be associated with apparent ophthalmoplegia due to tethering of the extraocular muscles, particularly the medial and inferior rectus muscles, such that diplopia occurs on upward or lateral gaze (dysthyroid eye disease; Fig. 16.13). These ocular signs are especially important in the diagnosis of autoimmune thyroid disease (Graves’ disease). It must be remembered that unilateral proptosis may also occur with an orbital tumour. Lid retraction, evident as a wide-eyed staring expression, and lid lag, in which depression of the upper lid lags behind the eye in a downward gaze, are due to increased activity of the sympathetic innervation of levator palpebri superioris and are not specific to Graves’ disease. Any degree of corneal exposure due to failure of complete lid apposition should be documented.

Visual acuity should be measured both with and without a pinhole to correct for any refractive error. Reduced acuity may be a feature of optic nerve compression in severe dysthyroid eye disease or of asymmetrical pressure on the optic chiasm due to hypothalamopituitary space-occupying lesions. In the latter, assessment of the visual fields may reveal a bitemporal hemianopia; this is frequently incomplete and incongruous, reflecting the asymmetrical growth of the tumour. A detailed description of the visual pathways and examination of the visual fields is given in Chapter 19. In the context of suspected pituitary/peripituitary disease, use of a red object (e.g. a hat pin) is preferable to finger movements as this provides a more sensitive marker of early visual pathway compression. Examination of the optic discs with the ophthalmoscope may show papilloedema, indicating recent onset of optic nerve compression, or pallor, indicating neural atrophy resulting from longstanding pressure. In the context of a pituitary mass lesion, pallor of the optic discs suggests that full visual recovery is improbable.

Investigation

Endocrine stimulation tests

Insulin tolerance testing, in which carefully controlled insulin-induced hypoglycaemia stimulates hypothalamopituitary secretion measured by serum growth hormone, cortisol and prolactin.

Insulin tolerance testing, in which carefully controlled insulin-induced hypoglycaemia stimulates hypothalamopituitary secretion measured by serum growth hormone, cortisol and prolactin.

Tetracosactrin testing, in which an injection of a synthetic ACTH analogue is used to assess adrenocortical reserve.

Tetracosactrin testing, in which an injection of a synthetic ACTH analogue is used to assess adrenocortical reserve.

Oral glucose tolerance test, which is an indirect test of insulin secretion and action as determined by the rise and subsequent fall in the plasma glucose level following an oral glucose load.

Oral glucose tolerance test, which is an indirect test of insulin secretion and action as determined by the rise and subsequent fall in the plasma glucose level following an oral glucose load.

Endocrine imaging

Plain X-ray imaging is of limited value in the investigation of endocrine disorders. However, lateral and anteroposterior views of the pituitary fossa can be useful in demonstrating abnormal calcification in the fossa, or gross expansion and erosion of the fossa due to large intrasellar or suprasellar tumours. Plain abdominal radiology may show renal calcification (nephrocalcinosis; Fig. 16.14) in patients with longstanding hypercalcaemia or renal tubular acidosis.

Figure 16.14 Widespread renal calcification typical of nephrocalcinosis in a patient with longstanding hyperparathyroidism.

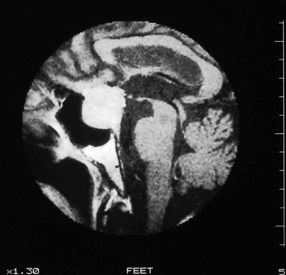

Computed tomography (CT) imaging is useful in assessing the pituitary, adrenal glands (Fig. 16.15) and thorax. However, MR imaging of the pituitary (Fig. 16.16) offers definite advantages over CT in terms of improved precision in detecting small intrasellar tumours, and better definition of the lateral border of the pituitary and the cavernous sinus.

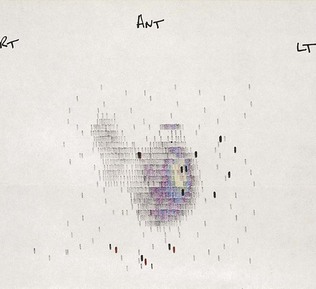

Isotopic imaging is particularly useful for demonstrating autonomous function within endocrine tumours. This technique is applicable to the thyroid gland (radiolabelled pertechnetate; Fig. 16.17) the adrenal medulla (radiolabelled metaiodobenzylguanidine) and parathyroids (combined radiolabelled sesta methoxy-isobutyl-isonitrile (MIBI) and pertechnetate differential scanning).