Objectives

• Identify the components of an endocrine history.

• Describe clinical findings in patients with pancreatic and posterior pituitary dysfunction.

• Explain the clinical significance of laboratory and diagnostic tests of pancreatic dysfunction.

![]()

Be sure to check out the bonus material, including free self-assessment exercises, on the Evolve web site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Urden/priorities/.

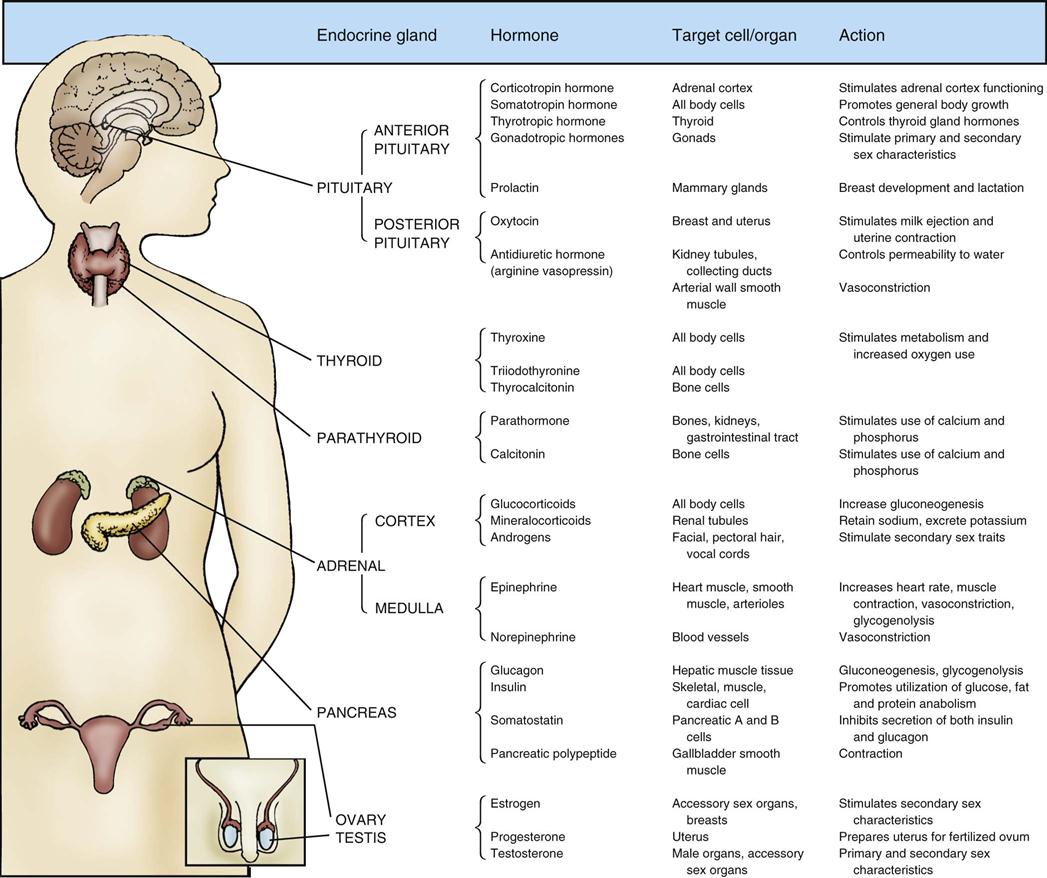

Assessment of the patient with endocrine dysfunction is a systematic process that incorporates the history and the physical examination. Most of the endocrine glands are deeply encased in the human body. Although the placement of the glands provides security, their inaccessibility limits clinical examination. The location of the endocrine glands, with the hormones they produce, target cells or organs, and hormonal actions, is presented in Figure 23-1. This chapter describes clinical and diagnostic evaluation of the pancreas and posterior pituitary gland.

History

The initial presentation of the patient determines the rapidity and direction of the interview. For a patient in acute distress, the history is curtailed to only a few questions about the patient’s chief complaint and precipitating events. For the patient without obvious distress, the endocrine history focuses on five areas: current health status, description of the current illness, medical history, general endocrine status, and family history.

Pancreas

Physical Assessment

Nursing priorities for physical assessment of the patient with pancreatic dysfunction focus on (1) hyperglycemia and (2) hypoglycemia.

Insulin, which is produced by the pancreas, is responsible for glucose metabolism. The clinical assessment provides information about pancreatic functioning. Hyperglycemia is the clinical manifestation of abnormal glucose metabolism.1,2 Patients with hyperglycemia may ultimately be diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes1,2 or be hyperglycemic in association with a severe critical illness.1,3 Hypoglycemia is often a complication of intensive insulin therapy. These conditions have specific identifying features as described in further detail in Chapter 24. Data collection for diabetic complications is outlined in Box 23-1.

Hyperglycemia

Because severe hyperglycemia affects a variety of body systems, all systems are assessed. The patient may complain of blurred vision, headache, weakness, fatigue, drowsiness, anorexia, nausea, and abdominal pain. On inspection, the patient has flushed skin, polyuria, polydipsia, vomiting, and evidence of dehydration. Progressive deterioration in the level of consciousness, from alert to lethargic or comatose, is observed as the hyperglycemia exacerbates. If ketoacidosis occurs, the patient’s breathing becomes deep and rapid (Kussmaul respirations), and the breath may have a fruity odor. Auscultation of the abdomen may reveal hypoactive bowel sounds. Palpation elicits abdominal tenderness. Percussion may reveal diminished deep tendon reflexes. Because hyperglycemia results in osmotic diuresis, the patient’s fluid volume status is assessed. Signs of dehydration include tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, and poor skin turgor. The key laboratory tests that confirm the assessment of hyperglycemia are discussed under laboratory studies.

Hypoglycemia

Patients with hypoglycemia may experience symptoms of tiredness, extreme hunger, headache, dizziness or blurred vision. On inspection, the skin may be diaphoretic, cool and clammy, or sweaty. Hands may be shaky with decreased coordination. Deterioration in the level of consciousness, from alert to disorientated, lethargic to coma occur. Seizures can occur with hypoglycemia. Although hypoglycemia can be suspected from physical signs and symptoms, a blood glucose level, as described under laboratory studies, is required to confirm this suspicion.

Laboratory Studies

Pertinent laboratory tests for pancreatic function measure short-term and long-term blood glucose levels, which can identify and diagnose diabetes.

Blood Glucose

The fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level is assessed by a simple blood test after the person has not eaten for 8 hours.1 A normal FPG level is between 70 and 100 mg/dL.1 A fasting glucose level between 100 and 125 mg/dL identifies a person who is prediabetic. Even prediabetic individuals are at increased risk for complications of diabetes such as coronary heart disease and stroke. An FPG level of 126 mg/dL (7 mmol/L) or higher is diagnostic of diabetes (Table 23-1). In non-urgent settings, the test is repeated on another day to ensure the result is accurate. In a patient with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia as described above, a non-fasting blood glucose level above 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol\L) suggests diabetes.1,2 After a meal, the concentration of glucose will increase in the bloodstream. Postprandial glucose levels should never exceed 180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L).4

TABLE 23-1

| PATIENT STATUS LEVEL | (mg/dL) | LEVEL (mmol/L) |

| Hypoglycemia | <70 | <3.9 |

| Normal FPG level | 70-100 | ≥3.9-5.6 |

| Impaired FPG level pre-diabetes* | 100-125 | 5.6-6.9 |

| Fasting FPG level diagnostic of diabetes | ≥126 | ≥7.0 |

| Non-FPG level diagnostic of diabetes | ≥200 | ≥11.1 |

*Intermediate group whose FPG levels do not meet the criteria for diabetes but are too high to be considered normal.

Data from American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2010, Diabetes Care 33(Suppl 1):S11, 2010.

All hospitalized patients must have their blood glucose levels monitored frequently while in the hospital.1 Clinical practice guidelines from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommend a target blood glucose level of 140 to 180 mg/dL in the critically ill.5 This range was selected to increase patient safety while on continuous insulin infusions by decreasing the risk of hypoglycemia.

When a continuous insulin infusion is administered, point-of-care blood glucose testing is performed hourly or according to hospital protocol by the critical care nurse to achieve and maintain the blood glucose within the target range.1,5

Hypoglycemia is defined as a blood glucose level below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).1,5,6 Severe hypoglycemia is defined as a blood glucose level below 40 mg/dL. Not all patients with hypoglycemia experience symptoms such as fatigue, hunger, diaphoresis, and dizziness. With severe hypoglycemia, mental status changes leading to coma can occur. A complication of intensive glucose control is that hypoglycemic episodes may occur more frequently.5–7 Critically ill patients at risk of hypoglycemia are usually placed on a regimen of routine blood glucose checks using bedside point-of-care testing.

Before discharge to home, diabetic patients should be taught to monitor their blood glucose levels.1,4,7 Maintaining blood glucose within the normal range is associated with fewer types of diabetes-related complications and a lower rate of complications of diabetes.4 Laboratory tests and point-of-care or self-monitoring of blood glucose represent the standard of care for management of diabetes. Unfortunately, home monitoring of blood glucose is not the norm, despite research evidence that maintaining blood glucose levels as close to normal as possible prolongs life and reduces complications. Only 40% of patients with type 1 diabetes and 26% of patients with type 2 diabetes monitor their blood glucose levels at least once daily.4

Urine Glucose

Testing the urine for glucose is not recommended for diabetic patients because there is too much variation in the renal threshold for glucose when diabetes-related kidney damage has occurred.4 Urine glucose measurements are affected by variation in fluid intake, reflect an average glucose level, and not a specific point in time, and are altered by some drugs. Urine glucose testing does not offer any help in the identification of hypoglycemia.4 For all of these reasons, urine testing is not recommended.

Glycated Hemoglobin

Blood testing of glucose is useful for daily management of diabetes. However, a different blood test is used to achieve an objective measure of blood glucose over an extended period. The glycated hemoglobin test (also known as glycosylated hemoglobin [HbA1C or A1C]) provides information about the average amount of glucose that has been present in the patient’s bloodstream over the previous 3 to 4 months.4 During the 120-day life span of red blood cells (erythrocytes), the hemoglobin within each cell binds to the available blood glucose through a process known as glycosylation. Typically, 4% to 6% of hemoglobin contains the glucose group A1C. A normal HbA1C value is 4% to 6%. HbA1C values above 6.5% are diagnostic for diabetes.1 For individuals with established diabetes, below 7% is the suggested HbA1C target to decrease the risk of microvascular and cardiac complications.1 The HbA1C value correlates with specific blood glucose levels as shown in Table 23-2.1 Not all clinical laboratories use the same analytic techniques to measure the glycated hemoglobin A1C, and methods to standardize the reporting of results worldwide are being developed.4,8 The American Diabetes Association recommends use of the HbA1C value both during initial assessment of diabetes mellitus, and for follow-up to monitor treatment effectiveness.1

TABLE 23-2

CORRELATION BETWEEN HEMOGLOBIN A1C CONCENTRATION AND PLASMA GLUCOSE LEVEL

| HbA1C (%) | MEAN PLASMA GLUCOSE LEVEL (mg/dL) | MEAN PLASMA GLUCOSE LEVEL (mmol/L) |

| 6 | 126 | 7.0 |

| 7 | 154 | 8.6 |

| 8 | 183 | 10.2 |

| 9 | 212 | 11.8 |

| 10 | 240 | 13.4 |

| 11 | 269 | 14.9 |

| 12 | 298 | 16.5 |

Data from American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2010, Diabetes Care 33(Suppl 1):S11, 2010.

Blood Ketones

Ketones (acetoacetate, β-hydroxybutyrate, and acetone) are by-products of fat metabolism. In most cases, when the body uses carbohydrate as its main source of energy, the liver completes fat metabolism, and minimal or no ketones are found in the blood. Ketone levels in the blood rise in acute illness, fasting, and with sustained elevation of blood glucose in type 1 diabetes when there is insufficient insulin. Home monitors to test capillary blood for elevated ketones (generally β-hydroxybutyrate) are recommended for type 1 diabetics in times of illness or stress.4

Elevated levels of ketones (ketonemia) are also detected by a fruity, sweet-smelling odor on the exhaled breath. This distinctive breath odor derives from the elimination of acetone as part of the compensatory response to maintain a normal pH. Ketones are also eliminated in the urine.

Urine Ketones

Urine ketone monitoring is important for critically ill patients with type 1 diabetes.4 The presence of ketones in urine is retrospective and indicates that blood ketones were elevated. In diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), fat breakdown (lipolysis) occurs so rapidly that fat metabolism is incomplete, and ketone bodies (acetone, β-hydroxybutyric acid, and acetoacetic acid) accumulate in the blood (ketonemia) and are excreted in the urine (ketonuria). It is recommended that all diabetic patients self-test or have their blood or urine tested for the presence of ketones during any acute illness or stress with a blood glucose level greater than 250 mg/dL, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain; and for women during pregnancy.

Normally, in healthy non-fasting individuals, only minute quantities of ketones are present in the urine, and these low levels are below the threshold of detection with routine testing methods.4 In fasting and starvation states, ketones may be present in the urine.4

Pituitary Gland

The pituitary gland, recessed in the base of the cranium, is not accessible to physical assessment. One essential hormone formed in the hypothalamus but secreted through the posterior pituitary gland is antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also known as vasopressin.

Physical Assessment

Nursing priorities for physical assessment of the patient with pituitary gland dysfunction focus on (1) hydration status, (2) vital signs, and (3) accurate intake and output.

ADH controls the amount of fluid lost and retained within the body. Acute dysfunction of the posterior pituitary or the hypothalamus can result in insufficient or excessive ADH production. The clinical signs of posterior pituitary dysfunction often manifest as fluid volume deficit (insufficient ADH production) or fluid volume excess (excessive ADH production).

Hydration Status

The nurse determines the effectiveness of ADH production by conducting a hydration assessment. A hydration assessment includes observations of skin integrity, skin turgor, and buccal membrane moisture. Moist, shiny buccal membranes indicate satisfactory fluid balance. Skin turgor that is resilient and returns to its original position in less than 3 seconds after being pinched or lifted indicates adequate skin elasticity. Skin over the forehead, clavicle, and sternum is the most reliable for testing tissue turgor because it is less affected by aging and more easily assessed for changes related to fluid balance. A well-hydrated patient has skin in the groin and axilla that is slightly moist to touch. In older patients, these typical assessment findings may be absent. Older persons, especially women, experience as much as a 50% decrease in total-body water content by age 75.9

Other indicators that the patient’s hydration status is adequate for metabolic demands include a balanced intake and output and absence of thirst. Absence of thirst, however, is not a reliable indicator of dehydration in the older adult or in critically ill patients. Indicators of normal hydration include absence of edema, stable weight, and normal urine specific gravity that falls within the normal range (1.005 to 1.030).

Vital Signs

Changes in heart rate, blood pressure, and central venous pressure (when available) are useful adjuncts to changes in fluid volume status. Blood pressure and pulse are monitored frequently. Decreased blood pressure with increased pulse is characteristic of hypovolemia, whereas elevated blood pressure and a rapid, bounding pulse may indicate hypervolemia. Orthostatic hypotension, which occurs when intravascular fluid volume decreases, is identified by a drop in systolic blood pressure of 20 mm Hg or a drop in diastolic blood pressure of 10 mm Hg when the patient changes position from lying to standing.

Weight Changes and Intake and Output

Daily weight changes coincide with fluid retention and fluid loss. Sudden changes in weight can result from a change in fluid balance; 1 L of fluid lost or retained is equal to approximately 2.2 pounds, or 1 kg, of weight gained or lost. To use weight as a true determinant of the fluid balance, all extraneous variables are eliminated, and the same scale is used at the same time each day. Precise measurement and notation of intake and output are used as criteria for fluid replacement therapy.

Laboratory Assessment

No single diagnostic test identifies dysfunction of the posterior pituitary gland. Diagnosis is made through an array of laboratory tests combined with the clinical profile of the patient.

Serum Antidiuretic Hormone

The result of a blood test for normal levels of serum ADH is 1 to 5 pg/mL.9 To prepare the patient for the test, all drugs that may alter the release of ADH are withheld for a minimum of 8 hours. Common medications that affect ADH levels include morphine sulfate, lithium carbonate, chlorothiazide, carbamazepine, oxytocin, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).10 Nicotine, alcohol, positive-pressure and negative-pressure ventilation, and emotional stress also influence ADH levels and must be considered in the interpretation of values.

The test, which is read by comparing serum ADH levels with the blood and urine osmolality, is helpful in differentiating the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) from central diabetes insipidus (DI). Increased ADH levels in the bloodstream compared with a low serum osmolality and elevated urine osmolality confirms the diagnosis of SIADH. Reduced levels of serum ADH in a patient with high serum osmolality, hypernatremia, and reduced urine concentration signal central DI. Chapter 18 provides more information about SIADH and DI.

Urine and Serum Osmolality

Values for serum osmolality in the bloodstream range from 275 to 295 mOsm/kg H2O. Osmolality measurements determine the concentration of dissolved particles in a solution. In a healthy person, a change in the concentration of solutes triggers a chain of events to maintain adequate serum dilution. Urine osmolality in the person with normal kidneys depends on fluid intake. With high fluid intake, particle dilution is low but will increase if fluids are restricted, and the expected range for urine osmolality therefore is wide, ranging from 50 to 1400 mOsm/kg.

Increased serum osmolality stimulates the release of ADH, which reduces the amount of water lost through the kidney. Body fluid thereby is retained to dilute the particle concentration in the bloodstream. Decreased serum osmolality inhibits the release of ADH, the kidney tubules increase their permeability, and fluid is eliminated from the body in an attempt to regain normal concentration of particles in the bloodstream. The most accurate measures of the body’s fluid balance are obtained when urine and blood samples are collected simultaneously.

Antidiuretic Hormone Test

The ADH test is used to differentiate neurogenic DI (central) from nephrogenic (kidney) DI. The patient is challenged with 0.05 to 1.0 mL of intranasally administered ADH in the form of desmopressin (1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin [DDAVP]).11 An intravenous line is inserted before ADH administration, and urine volume and osmolality are measured every 30 minutes for 2 hours before and after the ADH challenge. The patient with normal posterior pituitary function responds to the exogenous ADH by resorbing water at the kidney tubule and raising the urine osmolality slightly. In cases of severe central DI, in which the pituitary is affected, the urine osmolality shows a significant increase (becomes more concentrated), which indicates that the cell receptor sites on the kidney tubules are responsive to vasopressin.

Test results in which urine osmolality remains unchanged indicate nephrogenic DI, suggesting kidney dysfunction because the kidneys are no longer responsive to ADH. This test is rarely performed in the critical care unit because of the unstable hemodynamic and volume status of most patients.11

Diagnostic Procedures

In addition to laboratory tests, radiographic examination, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used to diagnose structural lesions such as cranial bone fractures, tumors, or blood clots in the region of the pituitary. Although these procedures do not diagnose DI or SIADH, they are useful in uncovering the likely underlying cause.11,12

Radiographic Examination

A basic x-ray examination of the inferior skull views the sella turcica and surrounding bone formation. Bone fractures or tissue swelling at the base of the brain, which are apparent on a radiograph, suggest interference with the vascular supply and nerve impulses to the hypothalamic-pituitary system. Dysfunction can occur if the hypothalamus, infundibular stalk, or pituitary is impaired.

Computed Tomography

CT of the base of the skull identifies pituitary tumors, blood clots, cysts, nodules, or other soft tissue masses. This rapid procedure causes no discomfort except that it requires the patient to lie perfectly still. CT studies can be performed with radiopaque contrast (sodium iodine solution) or without contrast. The contrast dye is given intravenously to highlight the hypothalamus, infundibular stalk, and pituitary gland. This dye may cause allergic reactions in iodine-sensitive persons, and the patient must be carefully questioned about iodine allergy before the test. The size and shape of the sella turcica and the position of the hypothalamus, infundibular stalk, and pituitary are identified.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI enables the radiologist to visualize internal organs and cellular characteristics of specific tissues. MRI uses a magnetic field rather than radiation to produce high-resolution, cross-sectional images. The soft brain tissue and surrounding cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) make the brain especially suited to MRI. Although not a definitive diagnostic test for posterior pituitary hormonal imbalance, MRI may identify anatomic disruption of the gland and the surrounding area to uncover a primary cause of DI or SIADH.