Chapter 33

Endocarditis and Endocarditis Prophylaxis

1. What are believed to be the first steps in the development of infective endocarditis (IE)?

2. How often does routine tooth brushing and flossing cause transient bacteremia?

3. True or false: Prospective randomized placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated that antibiotic prophylaxis before a dental or other procedure reduces the risk of IE?

4. What are the four conditions identified as having the highest risk of adverse outcome from endocarditis for which prophylaxis with dental procedures is still recommended?

Certain cases of congenital heart disease (CHD), such as:

Certain cases of congenital heart disease (CHD), such as:

Cardiac transplantation recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy

Cardiac transplantation recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy

5. Which of the above AHA criteria for endocarditis prophylaxis is not recommended for prophylaxis in the 2009 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines?

Cardiac transplant recipients with valvulopathy. The 2009 ESC guidelines take an approach that is generally similar to that of the 2007 AHA guidelines on which conditions and which procedures should be considered for endocarditis prophylaxis. However, the ESC guidelines do not list cardiac transplant recipients with valvulopathy as a population that should receive prophylaxis, noting that prophylaxis in this group is not supported by strong evidence, and that the probability of IE from dental origin is extremely low in such patients.

6. In the new AHA guidelines, for those patients with conditions listed in Question 4, which dental procedures carry a recommendation of endocarditis prophylaxis?

The guidelines emphasize that all dental procedures that involve the manipulation of gingival tissue or the periapical region of teeth or perforation of the oral mucosa should receive endocarditis prophylaxis. Procedures that do not require prophylaxis include routine anesthetic injections through noninfected tissue, dental radiographs, placement of removable prosthodontic or orthodontic appliances, bleeding from trauma to the lips or oral mucosa, and select other procedures and manipulations. The guidelines emphasize that prophylaxis for the former mentioned procedures “may be reasonable for these patients,” although “its effectiveness is unknown” (and this prophylaxis recommendation is given a class IIb recommendation, with level of evidence C). New changes in the AHA guidelines on IE are summarized in Box 33-1.

7. For those patients with conditions for which antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended, undergoing dental procedures for which prophylaxis is recommended, what regimens are recommended?

Antibiotic treatment should be administered as a single dose before the procedure, with antimicrobial therapy directed against viridians group streptococci. Amoxicillin (2 g orally [PO]), administered 30 to 60 minutes before the procedure, is the first-line recommendation. Those unable to take oral medication can be treated with ampicillin (2 g intramuscularly [IM] or intravenously [IV]) or cefazolin or ceftriaxone (1 g IM or IV). For those allergic to the penicillins or ampicillin, potential agents to use include cephalexin, clindamycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, cefazolin, and ceftriaxone.

8. For what other procedures may prophylaxis be considered in patients with high-risk lesions?

Invasive procedures of the respiratory tract that involve incision or biopsy of the respiratory mucosa (e.g., tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy)

Invasive procedures of the respiratory tract that involve incision or biopsy of the respiratory mucosa (e.g., tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy)

Bronchoscopy with incision of the respiratory tract mucosa (but not otherwise for bronchoscopy)

Bronchoscopy with incision of the respiratory tract mucosa (but not otherwise for bronchoscopy)

Invasive respiratory tract procedures to treat an established infection (e.g., drainage of an abscess or empyema)

Invasive respiratory tract procedures to treat an established infection (e.g., drainage of an abscess or empyema)

Surgical procedures that involve infected skin, skin structures, or musculoskeletal tissue

Surgical procedures that involve infected skin, skin structures, or musculoskeletal tissue

9. Is endocarditis prophylaxis recommended in patients treated with coronary stents, pacemakers, or defibrillators, those undergoing transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), or those who have undergone coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) (without valve replacement)?

10. What factors (discussed in detail in the ESC guidelines on endocarditis) should raise the suspicion for endocarditis?

Bacteremia or sepsis of unknown cause

Bacteremia or sepsis of unknown cause

Constitutional symptoms such as unexplained malaise, weakness, arthralgias, and weight loss

Constitutional symptoms such as unexplained malaise, weakness, arthralgias, and weight loss

Hematuria, glomerulonephritis, and suspected renal infarction

Hematuria, glomerulonephritis, and suspected renal infarction

Embolic event of unknown origin

Embolic event of unknown origin

New heart murmur (primarily regurgitant murmurs)

New heart murmur (primarily regurgitant murmurs)

Unexplained new atrioventricular (AV) nodal conduction abnormality (prolonged PR interval, heart block)

Unexplained new atrioventricular (AV) nodal conduction abnormality (prolonged PR interval, heart block)

Multifocal or rapidly changing pulmonic infiltrates

Multifocal or rapidly changing pulmonic infiltrates

11. When should cardiac echo (echocardiography) be obtained in cases of suspected endocarditis?

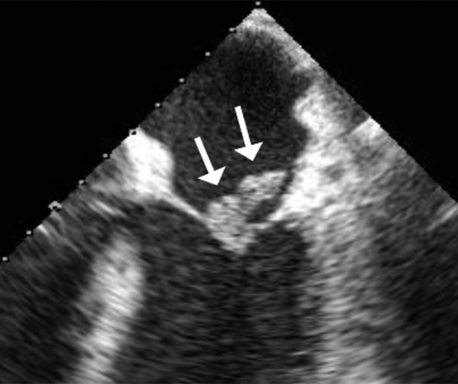

As soon as possible. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) has a sensitivity of 60% to 75% in the detection of native valve endocarditis. It can detect 70% of vegetations larger than 6 mm but only 25% of vegetations less than 5 mm. In cases where the clinical suspicion of endocarditis is low, a good-quality TTE is usually adequate. In cases where the suspicion of endocarditis is higher, a negative TTE should be followed by transesophageal echocardiography, which has a sensitivity of 88% to 100% and a specificity of 91% to 100% for native valves. TTE is not considered a sensitive test for prosthetic valve endocarditis, and a TEE is routinely obtained in such cases. TEE is also considerably more sensitive for detecting myocardial abscesses. Figure 33-1 demonstrates a mitral valve vegetation visualized by TEE.

Figure 33-1 A vegetation (arrows) on the mitral valve, as visualized by transesophageal echocardiography. (Courtesy Dr. Kumudha Ramasubbu.)

12. What is the procedure for obtaining blood cultures in cases of suspected endocarditis?

Three separate sets of blood cultures should be obtained, each at least 1 hour apart from the others (different authorities differ on the exact timing recommendations, but this is a reasonable ballpark figure). For what is called subacute IE, some experts recommend the cultures be drawn over a period of 24 hours. These blood cultures should not be obtained from intravenous lines (although some may recommend additional blood cultures be obtained from indwelling lines). At least 5 mL, and ideally 10 mL, of blood should be added to each culture bottle. In patients treated for a short period with antibiotics, one should wait, if possible, for at least 3 days after antibiotic discontinuation before obtaining new blood cultures.

13. What is the most common overall organism reported to cause endocarditis?

14. What is the most common organism causing subacute native valve endocarditis?

15. What is the most common organism causing endocarditis in intravenous drug abusers (IVDA)?

16. What is the most common organism causing early prosthetic valve endocarditis?

Staphylococcus infection, particularly S. epidermidis and S. aureus.

17. What is Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis often associated with?

18. What is the most common cause of culture-negative endocarditis?

19. How does one diagnose endocarditis caused by fastidious and nonculturable agents?

20. What is the mortality rate from IE?

21. Has the incidence or mortality from endocarditis decreased over the last three decades?

22. What are the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of endocarditis?

The Duke criteria is a set of criteria proposed for the definite and possible diagnosis of IE, published in 1994 (see Bibliography), based on both pathologic and clinical criteria. These criteria were a modification of previously proposed criteria (the Von Reyn criteria). These criteria were then themselves slightly modified in 2000, with the criteria incorporating the value of TEE, special recognition of Coxiella burnettii, and several other issues (see Bibliography). These revisions became known as the “modified Duke criteria” and are presented in Boxes 33-2 and 33-3.

23. What are some of the complications of endocarditis?

Valve destruction and development of regurgitant lesions (aortic insufficiency [AI] or mitral regurgitation [MR])

Valve destruction and development of regurgitant lesions (aortic insufficiency [AI] or mitral regurgitation [MR])

AV node heart block (as a result of abscess formation and extension to the area of the AV node and/or the bundle of His)

AV node heart block (as a result of abscess formation and extension to the area of the AV node and/or the bundle of His)

Prosthetic valve dehiscence and perivalvular leaks

Prosthetic valve dehiscence and perivalvular leaks

Peripheral embolization (brain, kidneys, spleen, lungs, etc.)

Peripheral embolization (brain, kidneys, spleen, lungs, etc.)

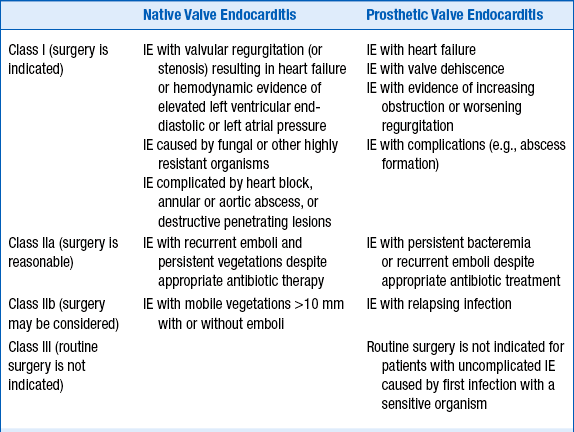

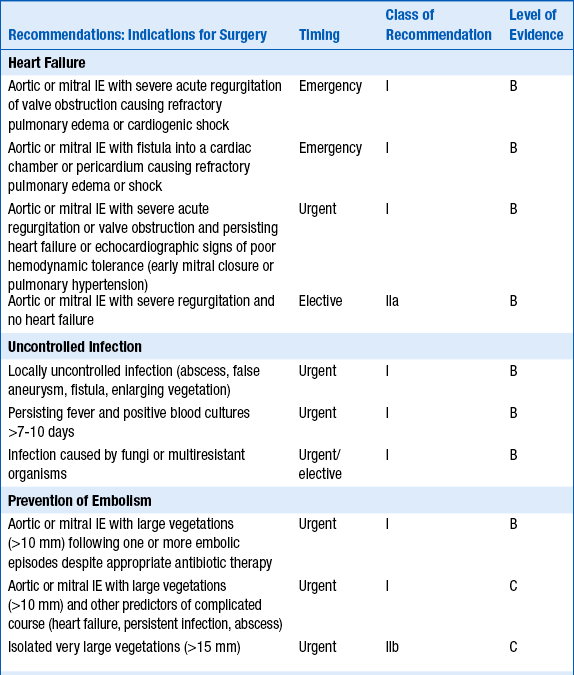

24. What are generally accepted indications for surgery in patients with active IE?

Decisions regarding surgery will depend both on the indications for surgery and the patient’s overall status and risks of surgery. Recommendations vary among the ACCF/AHA guidelines on valvular disease, the ESC guidelines on IE, and other experts who have weighed in on the topic. In general, accepted indications include acute AI or AR (or valvular stenosis) leading to heart failure, infection caused by fungi or other organisms not likely to be successfully treated with antibiotics, complications such as abscess formation, or recurrent embolism. Other potential indications for surgery include pseudoaneurysm, perforation, fistula, valve aneurysm, and dehiscence of a prosthetic valve. ACCF/AHA guidelines for surgery in cases of IE are summarized in Table 33-1; ESC guidelines for surgery are summarized in Table 33-2.

TABLE 33-1

SUMMARY OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY FOUNDATION/AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SURGERY FOR INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

Table created from text in RO Bonow, BA Carabello, C Kanu, et al: 2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 52:e1-e142, 2008.

TABLE 33-2

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE 2009 EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF CARDIOLOGY GUIDELINES ON THE PREVENTION, DIAGNOSIS, AND TREATMENT OF INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS: INDICATIONS AND TIMING OF SURGERY IN LEFT-SIDED NATIVE VALVE INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

Reproduced with permission from The Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009). Eur Heart J 30:2369-2413, 2009.

25. Are patients with mechanical prosthetic heart valves more likely to develop endocarditis than those with bioprosthetic heart valves?

Janeway lesions are irregular macules located on the hands and feet (Fig. 33-2). As opposed to Osler nodes, they are painless.

Figure 33-2 Janeway lesions in a patient with Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. (From Sande MA, Strausbaugh LJ: Infective endocarditis. In Hook EW, Mandell GL, Gwaltney JM Jr, et al, editors: Current concepts of infectious diseases, New York, 1977, Wiley Press.)

28. What is marantic endocarditis?

Marantic endocarditis is the term previously used for what is now referred to as nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis. The term reportedly derived from the Greek marantikos, meaning “wasting away.” The vegetations in NBTE are sterile and believed to be composed of platelets and fibrin. The finding of such sterile vegetations occurs in the setting of chronic wasting diseases, chronic infections (e.g., tuberculosis [TB], osteomyelitis), certain cancers, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. These often large vegetations may embolize to the brain, the coronary arteries, or the periphery.

29. What is Libman-Sacks endocarditis?

Libman-Sacks endocarditis is a form of NBTE seen in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Described in 1924, the vegetations most commonly occur on the mitral valve, although they can affect all four cardiac valves. The lesions are due to accumulations of immune complexes, fibrin, and mononuclear cells. Most lesions do not cause symptoms, although valvular regurgitation or stenosis can occasionally occur because of the lesions. Embolization of the lesions is rare.

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Bonow, R.O., Carabello, B.A., Kanu, C., et al. 2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:e1–e142.

2. Brusch, J.L. Infective Endocarditis. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/216650-overview. Accessed March 26, 2013

3. Durack, D.T., Lukes, A.S., Bright, D.K. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. Am J Med. 1994;96:200–209.

4. Horstkotte, D., Follath, F., Gutschik, E., et al. Guidelines on prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infective endocarditis executive summary; the task force on infective endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:267–276.

5. Li, J.S., Sexton, D.J., Mick, N., et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:633–638.

6. Mylonakis, E., Calderwood, S.B. Infective endocarditis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1318–1330.

7. Sexton DJ: Infective Endocarditis. In Basow, DS, editor: UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2013, UpToDate. Available at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/infective-endocarditis-historical-and-duke-criteria. Accessed March 26, 2013.

8. The Task Force on the Prevention. Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2369–2413.

9. Wilson, W., Taubert, K.A., Gewitz, M., et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;116:1736–1754.