End-of-Life Issues

End of life has become an important clinical topic in critical care, although requisite improvements in end-of-life care have been slow to follow. Because the primary purpose of admission of patients to a critical care unit is to provide aggressive, lifesaving treatment, the death of a patient is generally regarded as a failure. Because the culture emphasizes saving lives, the language that describes the end of life employs negative terms, such as “forgoing life-sustaining treatments,” “do not resuscitate (DNR),” and “withdrawal of life support.” Sometimes the phrase withdrawal of care is used, which can cause families to think there will be no comfort measures or assistance provided after a decision is made to discontinue mechanical ventilation and other life-sustaining treatments. This lack of end-of-life language has hampered literature searches until recently. The medical subject headings (MeSH) term for withdrawal of life support is passive euthanasia. Content on the end of life in medical1 and nursing2 critical care textbooks is minimal. The first textbook on end of life in critical care was published in 19983 and the second in 2001.4 Recently, more accurate language has been used in health care and popular literature to describe end-of-life decision making and medical interventions, such as allow natural death instead of “do not resuscitate” and withholding of non-beneficial treatment in place of “futile care.”5,6 This shift toward more realistic descriptors reflects extensive recent research in health care, especially palliative care, and the effectiveness of goals-of-care discussions in people with serious illnesses prior to crisis events.

More attention is being given to the quality of the end-of-life experience of people with serious illnesses, particularly those who become critically ill. Recent studies suggest that “medical care for patients with advanced illness is characterized by inadequately treated physical distress; fragmented care systems; poor communication between doctors, patients, and families; and enormous strains on family caregiver and support systems.”7 In addition to health care system barriers to good end-of-life care, mainstream media has significantly influenced misconceptions among the American population about the success rate of medical interventions in seriously ill people. A familiar media presentation of life and death in the hospital is a critical event in a patient who is resuscitated and immediately awakens with full capacity. In reality, treatment options are usually explained in rapid technical language, followed by a frightening question, “Do you want us to keep going?” or “Tell us what you want us to do.” This heavy burden placed on loved ones means they must choose between treatment options, one of which may result in loss of their loved one.

The emphasis on patient autonomy as a valued ethical principle is deeply embedded in the health care system of the United States. Expert medical recommendations are offered to patients and families and they must determine in a brief space of time whether those recommendations are aligned with their personal values. Most nurses are familiar with the scenario of families of critical care unit patients who are told how well one body organ is functioning being unable to understand why another physician communicates a poor prognosis. Less often, families are provided with a longer-term perspective that addresses the loss of functional status, decreased quality of life, and potential need for long-term care. Hope is a powerful influence on decision making, and a shift from hope for recovery to hope for a peaceful death should be guided by clinicians with exemplary communication skills. Strategies for communicating with critically ill patients and their families are further described in Chapter 6 (Box 6-2). Critical care nurses are often the interpreters of medical information and how it applies to personal preferences and values. The ability to respond realistically in accordance with the listener’s values and culture is a learned skill. Fortunately, many resources are available to further develop the necessary skills to better support patients and families through a critical care unit admission to discharge. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) has recognized the importance of this aspect of care in the critical care unit by developing protocols for palliative and end-of-life issues in the critical care unit and by identifying palliative and end-of-life care as a major advocacy initiative.8,9 Several key resources to enhance communication and elicit goals of care will be discussed throughout this chapter.

This chapter focuses on the evidence available for the care rendered to the dying critical care patient and his or her family through research reports and summaries of research and guidelines. One such report is from the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum,10 in which the preferred practices of the imminently dying are discussed. This type of report can be used to make a checklist of indicators for quality improvement in end-of-life care. Other reports that are specific to the critical care unit have been written by groups headed by Teno,11 Nelson,12 Glavan,13 Beckstrand,14 and Mularski.15 Curtis and Rubenfeld4 have provided a “how to” guide for critical care quality improvement to outline the process that can be used with these indicators. More recently, the Center to Advance Palliative Care has created a resource site for implementing palliative care in the critical care unit.16

End-of-Life Experience in Critical Care

Attention to the end of life of hospitalized patients has increased since the publication of the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment (SUPPORT).17 In this major report, more than 9000 seriously ill patients in five medical centers were studied. Despite an intervention to improve communication, shortcomings were found, aggressive treatment was common, only one half of physicians knew their patients’ preferences to avoid cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), more than one third of patients who died spent at least 10 days in a critical care unit, and for 50% of conscious patients, family members reported moderate to severe pain at least one half of the time.

Following closely after the publication of the SUPPORT study, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report, Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life.18 The group detailed deficiencies in care and gave seven recommendations to improve care:

1. Patients with fatal illnesses and their family should receive reliable, skillful, and supportive care.

2. Health professionals should improve care for the dying.

3. Policymakers and consumers should work with health professionals to improve quality and financing of care.

4. Health profession education should include end-of-life content.

5. Palliative care should be developed, possibly as a medical specialty.

6. Research on end of life should be funded.

7. The public should communicate more about the experience of dying and options available.

In SUPPORT and in the IOM report, critical care patients were not distinguished from other hospitalized patients, preventing distinctions to be made between types of units. To describe the number of deaths in critical care units, Angus and colleagues19 reviewed hospital discharge data from six states and the National Death Index. Of the more than 500,000 deaths studied, 38.3% were in hospitals, and 22% (59% of all hospital deaths) occurred after admission to the critical care unit. Terminal admissions associated with critical care accounted for 80% of all terminal hospitalization costs. The likelihood of dying in the hospital increased from age 25 to 74 years, and the likelihood of dying after critical care unit admission remained at 25% of all deaths for each age category.19 Although 90% of people would prefer to die in their own homes,18 more than 20% of those who died in this review received high-tech, aggressive care before they died.

An important shift in care of the terminally ill patient in the critical care unit has occurred with the growth of palliative care programs in the United States in the last decade. The rapid expansion of hospital-based palliative care programs has decreased the mortality rate in critical care units for patients followed by palliative care services through transfer to lower acuity, as well as decreased the costs associated with higher acuity critical care beds, pharmacy, laboratory, and diagnostic costs.20,21 Studies by Morrison and colleagues reviewed hospital and Medicare data to demonstrate that hospitals with palliative care services had significant cost savings in comparison to patients receiving usual care.21

Advance Directives

Although advance directives, also known as a living will or a health care power of attorney, were intended to ensure that patients received the care they desired at end of life, their enactment has been less than desired. Like other preventive measures, advance directives are underused, even though they are inexpensive and potentially effective.22 Completion rates in adults range from 16% to 36% overall with less than one half of seriously or terminally ill patients having documented their wishes.23 Most patients have expressed a desire to avoid “general life support” if dying or permanently unconscious, and few have expressed preferences regarding specific life-sustaining treatments; however, only about one third of physicians are aware of the existence of advance directives in their patients.24,25 Cook and others25 found that factors differed for determining the establishment of directives for advanced life support more than for informing a decision to limit or withdraw that support after admission to a critical care unit. Care providers also reported discomfort because they believed interventions were excessive and not compatible with an acceptable future quality of life. Even when advance directives are present, the question arises about whether they are applicable for current care decisions; in other words, is this a terminal illness?

Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment

The Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST) initiative began in Oregon in the 1990s when medical leaders collaborated to address the problem of patients’ advance directives not being honored.26 Different from an advance directive, POLST forms are medical orders that are honored across all treatment settings and are especially important to emergency responders in the community. Also, they are completed by the patient and physician in the presence of a serious chronic illness and should be incorporated into medical orders upon admission to the hospital or skilled nursing facility. POLST forms are more easily read than an advance directive in that the format is one of check boxes with specific directions. States that have approved use of POLST forms through legislation or specific regulations have witnessed a shift in proactive discussions of patients’ wishes for life-sustaining treatment.27,28 Preventing unwanted life-sustaining treatment through ongoing communication between patient and provider impacts the critical care setting in several ways. Treatment decision making is supported when prior discussions have occurred between physicians, patients, and their loved ones regarding declining health and limits on intervention. Resource utilization is maximized when inappropriate critical care unit admissions are prevented. Finally, moral distress of nurses is decreased when care is congruent with patient autonomy. Critical care nurses in states that recognize POLST forms need to be aware whether a regulatory mandate requires health care providers to honor the patient’s wishes documented on the form, or if the documentation is merely a guideline. Equally important is the need to identify the POLST form when it is presented and to communicate with medical staff to ensure that stated treatment wishes are incorporated into the plan of care.

Advance Care Planning

Cultural influences in the United States discourage discussion of death. Planning for decisions to be made at a later date if one is deemed incompetent is a difficult process, but this knowledge helps the family members left to make the treatment decisions. Advance care planning for those with chronic illness is advantageous for all involved.29 When surrogates hear the patient’s wishes for end-of-life care, they can be more congruent and knowledgeable about those wishes in future decision making. Significant effort has been expended on determining ideal interventions for the treatment and recovery from serious illnesses in the critical care setting. Currently, an equal amount of effort is being placed on providing adequate support and symptom management when recovery from illness is not likely to occur. This process may look different for individual patients or settings, but some guiding principles for a good death assist clinicians to identify what patients’ individual values are and where gaps in care exist that may be resolved (Box 11-1).30

Communication of the patient’s wishes between primary care providers and intensivists is critical. If patients have stated desires, they should be communicated when patients are transferred out of the critical care unit. If the patient has not specified his or her preferences, that information also is important and should be communicated to new health care providers; the level of care patients desire should be offered as appropriate. Families and care providers should be informed if patients decline aggressive care, so their families will not be left with difficult decisions in emergency situations. Emotional support for the patient and the family is important as they discuss advance care planning in the critical care setting and is described in the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) feature on Family Support in Box 6-3 in Chapter 6.

Ethical and Legal Issues

Two of the basic principles underlying the provision of health care are beneficence and nonmaleficence. Beneficence is the principle of intending to benefit the other through one’s actions. Nonmaleficence means to do no harm. Sometimes at end of life, these two principles are in conflict, such as when resuscitation is attempted under beneficence but causes harm to the patient, especially if resuscitation was not desired by the patient. An equally troubling situation exists when the fear of liability drives decision making from the clinician’s perspective. Medical recommendations for limitation of life-sustaining treatment or comfort care often result in conflict with surrogate decision makers. When life-sustaining interventions are offered, even though they are likely to be unsuccessful, families are given hope that their loved one may respond and recover. In family conferences, a shift in language and dialogue to distinguish non-beneficial treatment from interventions that may produce long-lasting benefit after discharge should occur early in the critical care unit stay. Most physicians and nurses have not been taught how to conduct this type of dialogue in their training. Fortunately there are many more options to gain the training and experience necessary to shift the decision making from a purely clinical perspective to a more humanistic view. Programs such as Education in Palliative and End-of-life Care (EPEC), End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) and the Center to Advance Palliative Care’s Palliative Care Leadership Center (PCLC) training are cost-effective methods to educate and support clinicians to more effectively communicate with patients and families at the end of life. Additional information on ethical and legal issues can be found in Chapter 2, Ethical Issues and Chapter 3, Legal Issues.

Comfort Care

The decision to withdraw life-sustaining treatments and switch to comfort care at end of life should be made with as much involvement of the patient as possible, including physical presence of the patient in decision making or procuring paper documents if the patient is not able to participate. If neither option is available, the patient’s intent as understood from discussions or knowledge of the patient should guide the decision about whether to withdraw treatment. Withholding and withdrawing care are considered to be morally and legally equivalent.31 However, because families experience more stress in withdrawing treatments than in withholding them,32 treatments should not be started that the patient would not want or that would not benefit him or her.

The goal of withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments is to remove treatments that are not beneficial and may be uncomfortable. Any treatment in this circumstance may be withheld or withdrawn. After the goal of comfort has been chosen, each procedure should be evaluated to see if it is necessary or causes discomfort. Treatments that cause discomfort do not need to be continued. Another defining question is whether treatments are prolonging the dying process. When disagreements arise, ethics consultations have been found to resolve conflicts regarding inappropriately prolonged, non-beneficial, or unwanted treatments in the critical care unit, shifting the focus to more appropriate comfort care.33

Forgoing life-sustaining treatments is not the same as active euthanasia or assisted suicide. Killing is an action causing another’s death, whereas allowing a person to die by withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment is avoiding any intervention that interferes with a natural death after illness or trauma.3

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

CPR was originally developed for those with coronary artery disease, and they are the most likely to survive resuscitation to discharge, as well as those who suffer cardiac arrest in the critical care unit.34 The benefits of resuscitation may be overestimated for survival and for the more relevant outcome of resumption of baseline functional status. In a meta-analysis of 51 studies, Ebell and colleagues34 found that the rate of overall survival to discharge after in-hospital CPR was 13.4%. A decreased rate of immediate survival was found for patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome, those with a hematocrit above 35%, and patients who were male. Decreased survival to discharge was related to sepsis on the day before resuscitation, cancer with or without metastasis, dementia, elevated serum creatinine level, African American race, and dependent status. Brindley and colleagues35 found the same rate for overall survival to hospital discharge (13.4%) in a retrospective study of hospital charts for inpatients who had undergone or experienced resuscitation. A study from Norway found that only 17% of older adult patients older than 75 years survived resuscitation to return home.36 The survival rate for cancer patients has risen from 2% to 6.7% since 1990 perhaps because better treatment and support have transformed many cancers into chronic diseases.37 It has also become evident that critical care unit patients don’t survive CPR as often as ward patients and overall functional status declined 25% in all survivors.37

FitzGerald and others38 found that functional status among almost half of the survivors of in-hospital CPR had deteriorated compared with their condition 2 months before the event. After 6 months, 30% of those patients had died, and two thirds continued to lose function. Despite these dismal statistics, CPR is offered as an option without fully informing patients or families of the low possibility of survival, the pain and suffering involved during and after the procedure, and the potential for decline in functional status.

Family members typically are asked to leave the room during resuscitation. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN)39 and the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA)40 have issued position statements recommending that families be allowed to be present during CPR and invasive procedures. Family presence is a significant source of support for the patient, and there may be a benefit to the family in observing the resuscitation that can aid in the grieving process when resuscitation is not successful by knowing that all was done that could be done.

Impact of Do Not Resuscitate Orders

As death approaches, the decision to initiate a DNR order is frequently delayed.41 A DNR order is intended to prevent the initiation of life-sustaining measures such as endotracheal intubation or CPR. In a review of the literature covering the 25 years since the DNR was established, Burns and colleagues42 found that those with a DNR order sometimes received less care and that some treatments were withheld43 without those changes being specified in the DNR order. Although acuity of illness and organ dysfunction consistently predicted mortality, only the medical history was positively associated with a DNR order for critically ill surgical patients.44 Documentation of consent conversations for DNR is less than ideal because the reasons for the DNR order were documented in only 55% of cases, and a consent conversation was documented in only 69%.45

Chang et al46 studied the effect of DNR orders in two critical care units in Taiwan and found that even though a DNR order was issued late in the clinical course, life-sustaining interventions were reduced through discussions and consent by surrogate decision makers. Nurses in Korea did not change their nursing activities substantially after receiving a DNR order, continuing to focus on maintenance, preventive, and hygiene tasks.47 They reported becoming more passive with interventions such as CVP monitoring, fluid and electrolyte balance, and reporting the patient’s condition. However, the nurses were more active in communicating with the family.

Prognostication and Prognostic Tools

Why patients who are dying would have received life-prolonging therapy or aggressive interventions shortly before their death can be explained in part by a series of studies. It was found that physicians’ ability to prognosticate the length of time before death is limited48,49 and that the time to death usually is overestimated. Patients’ wishes are often not known, can be vague even when they are known,50 or change over the course of an illness.51 Care may not be in accordance with patients’ wishes, and this discrepancy is more prevalent when comfort care is desired over aggressive care.52 Skills in communication and end-of-life care that would enable providers to better assess patient and family wishes are poorly developed and are not emphasized in medical curricula.53,54

Severity scoring systems belong to one of five classes: prognostic, disease-specific, single-organ failure, trauma scores, and organ dysfunction.55 Two common tools for estimating critical care unit mortality are the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) and multiple organ dysfunction score (MODS).56 However, when these tools were compared with physicians’ estimates of critical care unit survival of less than 10%, the physicians’ estimates were associated with subsequent life-support limitation. A physician’s estimate was more powerful in predicting mortality than illness severity, organ dysfunction, and use of inotropes or vasopressors.57

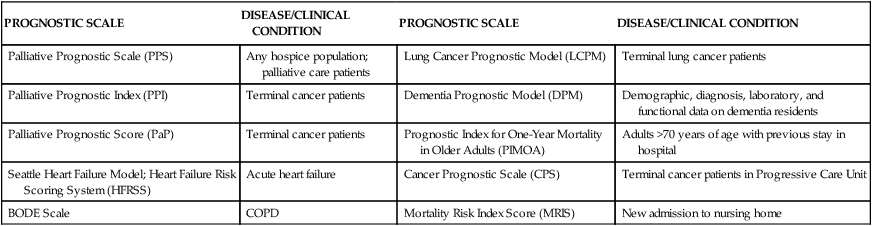

A majority of patients in the critical care unit have one or more chronic illnesses that greatly impact long-term recovery from major health events such as respiratory failure, myocardial infarction, or sepsis. In addition to use of prognostic tools specific to the critical care unit, it makes sense to incorporate prognostic tools for chronic illnesses into overall decision making and the communication process with patients and families. Scoring diagnoses with a traditionally poor prognosis or a consistent trajectory of functional decline can be helpful in comparing current health status with that which existed at the time of diagnosis. Loved ones of critically ill patients have witnessed the functional decline and may have hoped for improvement despite advancement of disease. Use of prognostic scales can add meaningful information to help patients and families make informed decisions. A summary of some of the more commonly used prognostic scales is listed in Table 11-1.58

TABLE 11-1

| PROGNOSTIC SCALE | DISEASE/CLINICAL CONDITION | PROGNOSTIC SCALE | DISEASE/CLINICAL CONDITION |

| Palliative Prognostic Scale (PPS) | Any hospice population; palliative care patients | Lung Cancer Prognostic Model (LCPM) | Terminal lung cancer patients |

| Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI) | Terminal cancer patients | Dementia Prognostic Model (DPM) | Demographic, diagnosis, laboratory, and functional data on dementia residents |

| Palliative Prognostic Score (PaP) | Terminal cancer patients | Prognostic Index for One-Year Mortality in Older Adults (PIMOA) | Adults >70 years of age with previous stay in hospital |

| Seattle Heart Failure Model; Heart Failure Risk Scoring System (HFRSS) | Acute heart failure | Cancer Prognostic Scale (CPS) | Terminal cancer patients in Progressive Care Unit |

| BODE Scale | COPD | Mortality Risk Index Score (MRIS) | New admission to nursing home |

Adapted from Lau F, et al. A systematic review of prognostic tools for estimating survival time in palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2007;23(2):93.

Despite this information and these tools, uncertainty remains a major issue in decision making for physicians, patients, and families.51 Because of uncertainty and because a few patients who were never thought likely to survive actually return to visit a critical care unit, professionals are not confident about issues of survivability. Moreover, many families cling to small hopes of survival and recovery.

Communication and Decision Making

Communication with the patient and family is critical. White and colleagues59 found that shared decision making about end-of-life treatment choices in physician-family conferences was often incomplete, especially among less educated families. Families were found to go through a process in their decision making in which they considered the personal domain (rallying support and evaluating quality of life), the critical care unit environment domain (chasing the doctors and relating to the health care team), and the decision domain (arriving at a new belief and making and communicating the decision).60 Higher levels of shared decision making were associated with greater family satisfaction. Regardless of the health literacy of the patient or family, simple language explanations of life-sustaining treatments such as CPR, ventilation, and tube feedings are necessary to effectively communicate. Many patients and families experience a “data dump” during communication with health care providers who focus on reporting vital statistics and odds of success. Several organizations have made available education handouts—some in multiple languages—that explain life-sustaining treatments in realistic terms that are intended to be accompanied by health care provider discussion.61,62 Focusing on improving critical care unit communication when patients are dying reduces lengths of stay and resource use.63

Patient Communication

Patients’ capacity for decision making is limited by illness severity; they are too sick or are hampered by the therapies or medications used to treat them.64 When decision making is required, the patient is the first person to be approached. Information that can assist the clinical team to facilitate and support health-related decision making is provided in the NIC feature on Decision-Making Support in Box 2-3 in Chapter 2. When the patient is not able to safely make health care decisions because of disease progression or the therapy used for treatment, written documents such as a living will or a health care power of attorney should be obtained when possible. Additional information on power of attorney for health care can be found in the section on “Advance Care Planning” earlier in this chapter. Without those documents, wishes of the patient should be ascertained from those closest to the patient. Some states have a legal order of priority for surrogates. Some patients have neither capacity nor surrogates to assist in decision making, accounting for up to 27% of deaths in one study.65

Family Communication

How questions are asked of surrogates is extremely important. The question is not “What do you want to do about (patient’s name)?” but rather “What would (patient’s name) want if he knew he were in this situation?” These two questions have vastly different meanings and consequences for the patient and the family. The former question has a greater likelihood of engendering guilt over “pulling the plug.” The latter question provides a sense of fulfilling the patient’s wishes and respecting choices. Sometimes, this discussion is held during the family meeting, in which a general sense of goals can be discussed. As families make decisions, they appreciate support for those decisions, because the support can reduce the burden they experience. There is some evidence from a French study that families are reluctant to participate in decision making.66 This evidence reinforces the need to support families who are highly stressed and possibly exhausted while they are trying to make the most difficult decisions they have ever faced.

Family members have reported dissatisfaction with communication and decision making.67 Increasing the frequency of communication and sharing concerns early in the hospitalization will make subsequent discussions easier for the patient, family, and health professional. Having the entire critical care unit team present for morning rounds is one method of improving communication.68 Family members who understood the communication of staff were acknowledged and comforted by them; those who had difficulties drew back and received less adequate communication.69 Families who reported increased understanding when communicating with staff also reported greater acknowledgment and comfort from staff members, whereas families who experienced a lack of understanding when communicating with staff tended to withdraw, further limiting the effectiveness in communication with the hospital staff. Having to focus on understanding the professional is an unacceptable burden.

A publication from the Society of Critical-Care Medicine (SCCM) recommends supporting the families of critical care unit patients.70 Forty-three recommendations are presented, including an endorsement of a shared decision-making model, family care conferencing, culturally appropriate requests for truth-telling and informed refusal, spiritual support, staff education and debriefing, family presence at rounds and resuscitation, open and flexible visitation, family-friendly signs, and family support before, during, and after a death. One use of this guideline is to assess the level of family support for each critical care unit so that the most deficient recommendations could be addressed with quality-improvement actions. The categories used in this guideline are for general support of critical care unit families. When cross-indexed with seven end-of-life domains,71 the needs of a family with a dying patient are decision making; spiritual and cultural support; emotional and practical support of families, including visitation and family preparation for death; and continuity of care.72

Cultural and Spiritual Influences on Communication

Cultural and spiritual influences on attitudes and beliefs about death and dying differ dramatically. The cultures of the predominant religions commonly seen in the surrounding community should be familiar to the local health care team. These differences may affect how the health care team is viewed, how decisions are made, whether aggressive treatment is preferred, how death is met, and how grieving will occur.73,74 Patients who do not follow a particular religion should be assessed for their individual spiritual beliefs, or lack thereof. Identifying sources of spiritual comfort strengthens the bond between caregivers, patients, or family. Satisfaction with critical care unit care has been associated with the extent to which the family is satisfied with their spiritual care, especially when the patient is near death.75 Staff members’ own attitudes about the specific practices of a culture should be carefully assessed76 and should be tempered with respect and humility. Interpreters are necessary when the patient or the family members do not speak English. A cultural and religious assessment is warranted in all situations, because cultural or religious affiliation does not imply that patients or families follow all of the tenets of that group.

Withdrawal or Withholding of Treatment

Discussions about the potential for impending death are never held early enough. Usually, the first discussion about prognosis occurs in conjunction with the topic of the discontinuation of life support. The late timing of that first discussion is an issue, particularly because some families have arrived at the notion of withdrawal before physicians.64,77 Equally important is that some family members dread such conversations but are grateful to discuss the uncertainty of their loved one’s future. Physicians should give families time to adjust to this information and make preparations by providing discussions early about prognosis, goals of therapy, and the patient’s wishes.4

Proactive Approach

After a poor prognosis is established, a period can elapse before end-of-life treatment goals are determined. Campbell and Guzman78 recommended a proactive case-finding approach by palliative care personnel to decrease hospital length of stay for patients with multiorgan system failure and global cerebral ischemia. They shortened the time between identifying the poor prognosis and establishing comfort care goals, decreased length of critical care unit stay for patients with multisystem organ dysfunction, and reduced the cost of care. Proactive palliative care should occur when admission diagnoses trigger a consultation instead of after several avenues of treatment have been exhausted. Case managers and social workers can be particularly helpful in this regard.

When patients are admitted with serious illnesses and are likely to die, a proactive approach to palliative care has been found to shorten critical care unit stays without a significant difference in mortality rates or discharge disposition.79 The use of nonbeneficial resources decreased, and prolonged dying was avoided.78 Patients with assistive cardiac devices present a different challenge in discussion of withdrawal of life support. Many times, these patients are cognitively intact and consent to removal of technology that is keeping them alive. Weigand and Kalowes outlined issues surrounding discontinuation of cardiac devices as a preventive ethics approach with health care providers anticipating the need to shift goals of care and support patients and families through the process.80

Disagreement and Distress for Caregivers

Nurses and doctors frequently disagree about the futility of interventions. Sometimes, nurses consider withdrawal before physicians and patients do, and they then feel the care they are giving is unnecessary and possibly harmful. Nurses in one study were found to be more pessimistic but more often correct than physicians about the prognoses of dying patients, but the nurses also proposed treatment withdrawal for some very sick patients who survived.81 This issue is a serious one for critical care nurses, because emotional and ethical distress can lead to burnout. Meltzer found that the score on the emotional exhaustion subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory and the score on the frequency subscale on the Moral Distress Scale correlated for a group of 60 critical care nurses.82 Often, critical care nurses experience moral distress due to the severity of patients’ illnesses as well as the requirement of technology to maintain vital organ function. Collaborative strategies for minimizing moral distress rely on the bedside nurse and critical care leadership to implement individual and organizational changes.83

Barriers to Dying

Ellershaw and Ward84 identified a number of barriers to diagnosing dying: hope for the patient to improve, unclear diagnosis, pursuance of futile interventions, disagreement about the patient’s condition, failure to recognize key signs and symptoms, poor ability to communicate, fears about foreshortening life, concerns about withdrawal and withholding, and medicolegal issues. Prognostic models are used to predict mortality rates for groups of critical care patients, not to guide specific decisions to forgo treatment.85 This perspective is changing with the increased availability of end-of-life research recommendations, newer prognostic models, and the growth of palliative care services to support patients, families, and providers.

Steps Toward Comfort Care

If a series of interventions is to be withdrawn, dialysis usually is discontinued first along with diagnostic tests and vasopressors. Next, intravenous fluids, monitoring, laboratory tests, and antibiotics are stopped.85 Withdrawal of specific treatments may have effects necessitating symptom management. Withdrawal of dialysis may cause dyspnea from volume overload, which may necessitate the use of opioids or benzodiazepines. Efforts to discontinue artificial feeding may be met with concern from the family, because offering food has great social significance. It is essential to share information with family and providers regarding the potential benefits of withholding food and fluids in the days immediately prior to death to prevent unnecessary suffering.86

Palliative Care

The growth of palliative care programs in the United States has demonstrated the importance of this new health care specialty, with a 125% increase from 2000 to 2008.20 Initiatives such as the IPAL-ICU have demonstrated that a focus on life-saving interventions can be integrated with palliative care concurrently, rather than one following the failure of another.20 Evidence-based clinical, communication, and quality tools are available through the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC). Resources include templates for

• Family conference documentation

• Quality of palliative care surveys

• Pocket reference cards on pain, family conferences, and communication

• Model policies for ventilator withdrawal and medical futility

Patients who are identified as being near the end of life require aggressive care for their symptom management, provided by a team of health professionals. The most relevant clinical goal is to palliate these unpleasant situations by assessing for them and implementing appropriate interventions.3 Palliative care guidelines have been released by a consortium of organizations concerned with palliative care and end-of-life care, and they may provide guidance when the usual first-line treatments do not promote comfort for critically ill patients who are near death.87 Strategies that are based on research evidence and expert opinion for specific conditions such as delirium, opioid dose escalation, and dyspnea at the end of life are outlined on the End of Life/Palliative Education Resource Center (EPERC) website.88 Palliative care has been thought of as desirable only when the patient nears death or when several interventions have been tried for management of symptoms without success. However, publications such as these guidelines and the IOM report Improving Palliative Care for Cancer89 have stated that palliative care ideally begins at the time of diagnosis of a life-threatening illness and continues through cure or until death and into the family’s bereavement period.

Pain Management

Because many critical care patients are not conscious, assessment of pain and other symptoms becomes more difficult.90 Gélinas and colleagues91 recommended using signs of body movements, neuromuscular signs, facial expressions, or responses to physical examination for pain assessment in patients with altered consciousness (see Chapter 9). Foley,92 while acknowledging the usual three-step approach of the World Health Organization, admitted that in critical care units, step 3 is frequently used because of the intensity of the pain.

Nonopioid medications are the first-line approach, followed by adding an opioid for additional analgesia when relief is not obtained. Because opioids provide sedation, anxiolysis, and analgesia, they are particularly beneficial in the ventilated patient. Morphine is the medication of choice, and there is no upper limit in dosing.3 In nonventilated patients, sedation may cause respiratory depression,92 and nonopioids or specific anesthetic agents may be more appropriate. In the sedated ventilated patient, especially those receiving neuromuscular blocking medications, there is no systematic, reliable method to determine presence or degree of pain.93 The absence of the usual clinical indicators of pain, such as grimacing or guarding, makes it a challenge to determine whether pain is present. Titration of intravenous infusions to achieve maximum effect with minimum sedation is an inexact science. Sedation/agitation scales are one method of monitoring the effectiveness of medications but are not performed continuously with frequent titration, such as during surgery. Potential pain sources include prone position, endotracheal tube, wounds, and immobility, and should necessitate preventive analgesia administration.93 Critical care nurses should assume pain is present in the immobile patient and administer routine analgesics to prevent suffering. Jacobi and others94 published a guideline for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesia (see Chapter 10); it is also available on the SCCM’s website (http://www.sccm.org).

Symptom Management

It has long been in question whether critical care patients can accurately report their symptoms because of the effects of sedating medications, severe illness, and organ dysfunction. Kalowes studied non-cancer critical care unit patients during a daily wake up and compared their report of symptoms with those of their family members.95 Almost all patients had more than 10 symptoms, and there was 85.5% congruence between patient and family report of physiologic and psychologic symptoms. Overall, patients experienced significant symptom burden near the end of life but received limited treatment to alleviate suffering.

Campbell,3 in her book chapter titled “Usual Care Requirements for the Patient Who Is Near Death,” listed the following symptoms as necessary parts of the assessment: dyspnea, nausea and vomiting, edema and pulmonary edema, anxiety and delirium, metabolic derangements, skin integrity, and anemia and hemorrhage.

Dyspnea

Campbell published a review of terminal dyspnea and respiratory distress.96 Dyspnea is best managed with close evaluation of the patient and the use of opioids, sedatives, and nonpharmacologic interventions (oxygen, positioning, and increased ambient air flow). Morphine reduces anxiety and muscle tension and increases pulmonary vasodilatation but is not effective when inhaled. Benzodiazepines may be used in patients who are not able to take opioids or for whom the respiratory effects are minimal. Benzodiazepines and opioids should be titrated to effect. Treatment efforts should be aimed at the patient’s expression of dyspnea rather than at respiratory rates or oxygen levels.97

Fever and Infection

Fever and infection necessitate assessment of the benefits of continuing antibiotics so as not to prolong the dying process.3 Management of the fever with antipyretics may be appropriate for the patient’s comfort, but other methods such as ice or hypothermia blankets should be balanced against the amount of distress the patient may experience.

Edema

Edema may cause discomfort, and diuretics may be effective if kidney function is intact. Dialysis is not warranted at the end of life. The use of fluids may contribute to the edema when kidney function is impaired and the body is slowing its functions. In a Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) report,98 little relationship was found between thirst and fluid therapy or fluid status.

Delirium

Delirium is commonly observed in the critically ill and in those approaching death. Haloperidol is recommended as useful, and restraints should be avoided. In a review of the available literature, Kehl99 concluded that despite the recommendations of most study authors to use neuroleptic medications as a treatment for restlessness, several studies demonstrated the effectiveness of other medications, such as benzodiazepines (notably midazolam and lorazepam) or phenothiazines, alone or in combination.

Near-Death Awareness

Two hospice nurses have described a phenomenon of near-death awareness.100 The same behaviors may be seen in conscious critical care patients near death. Having an awareness of the phenomenon enables more careful assessment of behaviors that may be interpreted as delirium, acid-base imbalance, or other metabolic derangements. These behaviors include communicating with someone who is not alive, preparing for travel, describing a place they can see, or even knowing when death will occur.101 Family members may find these behaviors disturbing but find comfort in understanding the phenomenon and in sharing these experiences with their loved one.

Family Meetings

Although family meetings should be held within 72 hours of an admission,102 they are frequently held to formulate a decision to withdraw life support. Lilly and colleagues102 found that an earlier meeting led to shorter critical care unit stays for patients who eventually died, and allowed them earlier access to palliative care. These results held up in a 4-year evaluation of this intervention, and they found that they were providing advanced life support to patients with the potential to survive and an earlier withdrawal when ineffective.103

Withdrawal of Mechanical Ventilation

A dramatic geographic variation in the prevalence of withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies has been found. Some evidence suggests this variation may be driven more by physicians’ attitudes and biases than by factors such as patients’ preferences or cultural differences.104 This inconsistency in care further complicates a difficult process. From the clinical, ethical, and legal perspectives, standardized withdrawal from life-support order sets are recommended to direct and support nursing judgment in this complex and emotional clinical situation.

Selph et al taped end-of-life conversations between families and physicians and found that at least one supportive statement was provided 66% of the time during the discussion.105 Recommendations for creating a supportive atmosphere during withdrawal discussions included

• Taking a moment at the beginning of the conversation to inquire about the family’s emotional state

• Acknowledging verbal and nonverbal expressions of emotion and using that to support families

• Acknowledging that most family members face a significant emotional burden when a loved one is critically ill or dying

During the family meeting in which a decision to withdraw life support is made, a time to initiate withdrawal is usually established. For example, a distant family member may need to arrive, and then the procedure will occur. When appropriate, the patient should be moved to a separate or special room. It is helpful if other staff members are alerted to the fact that a withdrawal is occurring. A neutral sign hung on the door or use of a special room may caution staff to avoid loud conversations and laughter, which is quite upsetting to grieving families. Nurses can support the family by suggesting specific measures to modify the environment and minimize symptoms that the family might perceive as suffering of their loved one.104

After the decision to remove ventilatory support is made and the family is gathered, the family should be told what the impending death will be like. When the patient is dependent on ventilatory support or vasopressors and that support is removed, death typically follows in minutes. The patient appears as if sleeping, and the usual signs of color and skin temperature changes will not be seen before death. The opposite is true if the patient is not ventilator dependent. When the patient will be extubated at the beginning of the withdrawal process, the family should be prepared for respiratory noises and gasping respirations. These signs are less likely when the endotracheal tube is removed near the end of the withdrawal process, as is more commonly done. When assessing how prepared family members felt for what would happen during withdrawal of life support, Kirchhoff and colleagues106 found that families who did not receive preparatory information before the withdrawal of life support requested this information during interviews 2 to 4 weeks after the patient’s death. Family members who received this recommended information felt significantly more prepared. Providing information to families for the experience of withdrawal alerts them to what the patient may exhibit as death approaches, reducing the distress families may feel during the withdrawal process.

Pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators should be turned off to prevent patient distress from their firing107 and to avoid interfering with the pronouncement of death.85 Wiegand and Kalowes108 provide detailed information about the conversations that should be held with the patient109 and how each of the specific devices are deactivated. Neuromuscular blocking agents should be discontinued, because paralysis precludes the assessment of the patient’s discomfort and the means of the patient to communicate with loved ones. Time for clearance of the medication should be carefully considered in planning the withdrawal process.85

The removal of monitors is usually recommended.110 However, physicians and nurses may use the monitor to assess the distress of the patient during the withdrawal process and to adjust the amount of medication needed for symptom management. Families may glance at the monitor to verify that electrical activity has ceased, because the appearance of death may be too subtle to detect. If not needed, monitors should be removed to make the room appear as normal as possible. It is important, however, to include family members in the decision-making process.

Opioids and Sedatives

Opioids and benzodiazepines are the most commonly administered medications, because dyspnea and anxiety are the usual symptoms related to ventilator withdrawal. Campbell111 stated that brain-dead patients do not require sedation and that patients with brainstem activity only may not show signs of distress or need sedation. Von Gunten and Weissman112 recommended sedating all patients, even those who are comatose. They recommend a bolus dose of morphine (2 to 10 mg IV) and a continuous morphine infusion at 50% of the bolus dose per hour. Midazolam (1 to 2 mg IV) is given, followed by an infusion at 1 mg/hr. The intent is to provide good symptom control so that doses accelerate until the patient’s comfort is achieved. Additional medication should be available at the bedside for immediate administration if discomfort is observed in the patient. In one study, the use of opioids or benzodiazepines to treat discomfort after the withdrawal of life support did not hasten death in critically ill patients.113

Ventilator Settings

All patients do not require the same ventilator weaning or extubation protocols. For example, Campbell111 recommended turning off the ventilator and extubating patients who are brain dead, placing patients who have brainstem-only injuries on a T-piece, and using terminal weaning for those with altered consciousness or those who are conscious. The terminal wean offers the most control over secretions, respiratory noises, and gasping.

Professional Issues

Health Care Settings

Professional issues surround the provision of palliative care within traditional acute and clinical settings. In critical care units, care may be managed by an intensivist or by a committee of specialists, but seldom by the family physician who knows the patient. The use of consultants may be limited. Palliative care specialists may be available at certain times, but they are often considered “outsiders” and are infrequently invited. How the consultation is arranged may vary by institution. Turf issues should not compromise patient care. Having a clear plan for withdrawal and better preparation of the family may assist the professionals involved in feeling more comfortable with the care provided.114 Expert nurses should advocate for vulnerable patients by communicating the patient’s wishes and presenting a realistic picture to family members.115

Some interventions have been found helpful for health professionals in improving patient care. Although it did not improve nurses’ assessment of patients’ dying experience, a standardized order form for withdrawal was found to increase the amount of medications nurses administered for sedation.116 Death rounds for critical care unit medical residents were well received and recommended to be included in future rotations.117

Emotional Support for the Nurse

Nurses who care for the dying patient need to have their work as valued as other high-tech functions in the critical care unit. Critical care units usually have several nurses who are looked to by other staff to provide end-of-life care or to assist with withdrawal of life support. When several deaths occur close together, those nurses may be called on frequently. Some consideration in assignment should be given when a nurse has more than one death in a shift or a week. Taking a new admission is also difficult immediately after a death, and it can occur before the family has left the unit. Nurse administrators can provide some additional resources, debriefing, or time off when the burden has been high. Hearing supportive words from colleagues has been reported by critical care nurses as helpful in coping with the death of a patient.118

Nurses experience moral distress when aggressive care is offered to patients who are not expected to benefit from it. These levels of distress are high and have implications for retention of highly skilled nurses.119 One study showed that nurses’ experience of moral distress and a negative ethical environment is more severe than that of their physician colleagues.120 Developing a consensus about care was found to be the most helpful approach.121 Nurses in this study had a number of suggestions when questioned about what could be done to improve end-of-life care, such as facilitating dying with dignity, having someone with patients who are dying, managing patients’ symptoms, knowing and then following patients’ wishes for end-of-life care, and promoting earlier cessation of treatment or not initiating aggressive treatment at all.

Until recently, end-of-life content in nursing school curriculums and textbooks was sparse, and continuing education was limited for licensed nurses on this topic. The End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) was created in 2000 to address gaps in education for nurses caring for dying patients. Based on national reports, guidelines, recommendations, and research studies, ELNEC has grown into the premier source of end-of-life training for nurses all over the world. The Critical Care ELNEC course became available in 2006 and addressed topics focused on the critical care unit setting.122

Organ Donation

Legal Issues

The Social Security Act Section 1138 requires that hospitals have written protocols for the identification of potential organ donors.123 The Joint Commission (TJC) has a standard on organ donation and there is a variety of state legislation to direct health care providers and organ recovery agencies.124 Although an impending death marks a difficult time for family members, the nurse must notify the organ procurement official to approach the family with a donation request. These individuals have training to make a supportive request and are the ones to decide whether a family should not be approached based on the patient’s disease. Although organ donation may not be appropriate in some cases, tissue donation remains a consideration. More information is available in Chapter 37.

Brain Death

Death may be pronounced when the patient meets a list of neurologic criteria. However, there are differences among hospital policies for certification of brain death, which may permit differences in the circumstances under which patients are pronounced dead in different U.S. hospitals.125 Families do not always understand the meaning of brain death, and they are less likely to donate organs when they believe the patient will not be dead until the ventilator is turned off and the heart stops.126 How these conversations are held will determine families’ understanding and positively affect donation. Campbell3 recommended not suggesting that the organs are alive while the brain is dead, but rather that the organs are functioning as a result of the machines used. Chapter 37 provides more information on the specifics of brain death.

Family Care

In this chapter, the term family means whatever the patient states is the family. An integral part of the patient-family dyad, families expect a cure for any condition the patient may have; they do not expect to receive bad news. They look for the good news in any message received from caregivers and are surprised when told that death is the only outcome possible.106 Families need assistance in forming their expectations about outcomes. Ongoing communication about the patient’s progress is preferable to waiting until the patient is near death and then communicating with the family. Most studies of families at this time are descriptive, and interventions need to be developed to help them.127

One intervention used with families at the end of life is the use of a grieving or comfort cart. In one critical care unit,128 the cart has a top drawer with English and Spanish versions of the Bible, Koran, and Book of Mormon and pamphlets about grief and bereavement. The lower portion of the cart holds paper cups, napkins, and condiments. Fresh coffee and tea are brewed on the unit and served with muffins and cookies from the cafeteria. Family responses have been positive because they do not want to leave the bedside despite their hunger. Another strategy is to provide nursing units with supplies to support the emotional and spiritual needs of families at the end of life that include religious items and music.129,130

Communication Needs

Families have complained about infrequent physician communication,131 unmet communication needs in the shift from aggressive to end-of-life care,132 and lacking or inadequate communication.133 Sometimes families are not ready to receive the prognosis and engage in decision making.134 Communication seems to be the most common source of complaints in families across studies and should be at the center of efforts to improve end-of-life care.

The health care team can reinforce the legitimacy of the family expressing feelings of disappointment, sadness, and loss. It is important that the family is made aware that the patient was more than a clinical disease and that he or she was recognized as an individual while in the critical care unit. When relatives of critical care unit patients were provided with a brochure on bereavement and received a proactive communication, they had lower negative scores on the Impact of Event Scale and on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Ways to address the cultural, social, and emotional issues surrounding the expression of grief are given in the NIC feature on Grief Work Facilitation (Box 11-2).135

Waiting for Good News

Patients and families do not come to the critical care unit with the expectation of death. Even those who have had previous admissions expect to be “saved.” They tend to listen to imparted information looking for good news; even when bad news is given, they may initially deny it or have great difficulty taking it in.133 Having this in mind while talking to families may assist professionals in interpreting families’ responses.

Families may refuse to forgo life-supporting treatments and want “everything done” because of mistrust of health professionals, poor communication, survivor guilt, or religious or cultural reasons.64 Effective communication throughout the hospitalization and information provided throughout the stay predispose the family to better acceptance of news as the patient deteriorates. Family satisfaction is increased when they feel supported during their decision making136,137 or hear more empathic statements from physicians.105

Family Meetings

Family meetings in the presence of the critical care team have been one method used to arrive at a common understanding of the patient’s prognosis and goals for future care.138,139 An analysis of the amount of time families had to speak in these meetings revealed that when families had greater opportunity to talk, their satisfaction with physician communication increased and their ratings of conflict with the physician decreased. Abbott and colleagues140 discussed families’ descriptions, 1 year after decisions about withdrawal of life support, of conflict centering on communication and the behavior of the staff. After the patient’s death, greater family satisfaction with withdrawal of life support was associated with the following measures141:

• The process of withdrawal of life support being well explained

• Withdrawal of life support proceeding as expected

• Patient appearing comfortable

• Family and friends being prepared

• Appropriate person initiating discussion

Curtis and colleagues142 have been studying the process of family meetings and how to improve them to promote better end-of-life care for critical care unit patients and their families. They found that the missed opportunities that occur during these meetings were occasions to listen to family, to acknowledge and address emotions, and to pursue key tenets of palliative care, such as patient preferences, surrogate decision making, and nonabandonment.

Family Presence During Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

To be helpful, the family’s presence during procedures or resuscitative attempts40 should be coupled with staff support. Critical care nurses and emergency nurses have taken family members to the bedside for resuscitation or invasive procedures, but most did not have written policies for the family’s presence.143 Sometimes, these experiences provide opportunities for the family to be supportive of the patient. At other times, the family may become more aware of what is involved in decisions they have made on behalf of the patient. Seeing the steps of resuscitation may make clearer the impact of decisions made or delayed.

Visiting Hours

Visiting in critical care units continues to be restricted,144 despite national calls for increases in patient or family control over the care.145 Restricting visiting for dying critical care unit patients seems to be unconscionable. Providing the visiting time to help family members say good-bye is an important function. Family members may have difficulty in seeing the person they knew among all the tubes. Coaching can be provided about how to approach the patient and about how the patient may still be able to hear despite appearing to be nonresponsive. Visitors should be permitted to the extent possible, while not interfering with other patients’ privacy or rest. Children, unless they represent a significant source of infection, should be allowed to say good-bye, but they may need adult assistance in understanding the situation. Families may have religious or cultural ceremonies that are important for them to perform before the patient dies or experiences withdrawal of life support. These practices should be encouraged and facilitated as much as possible. Continuity of care by the same nurse is important. As the patient nears death, nurses have sometimes stayed with the family after the end of a shift when death was imminent so that they would not need to adjust to another person at this difficult time.118

After Death

After the death, the family may wish to spend time at the bedside. The family members’ time with the body should be unhurried and private. They need adequate room to sit and spend time. They can be asked if they need assistance or resources and whether they wish to be alone or have someone nearby. Frequently, the bed is needed for another patient, and juggling is required to ensure that the family has sufficient time even as another patient needs to be admitted. Supporting families after a death involves immediate bereavement support, information on what to do about the death, bereavement support for the future, contact with the family after death, and assessment of the quality of care the patient experienced.146 Having material already prepared with the necessary after-death information is quite helpful at this time. Most hospices offer post-death bereavement support groups that are available to any member of the community free of charge, regardless of whether a loved one was enrolled in hospice. Nurses need to be aware of their own judgment on what is an appropriate response, because individuals respond differently to the same news, even within the same family.

Collaborative Care

The ability to provide collaborative, compassionate end-of-life care is the responsibility of all clinicians who work with the critically ill. Interdisciplinary collaborative efforts are associated with improvement in care.147 In 2008, the SCCM published a revised guideline, “Recommendations for End-of-Life Care in the Intensive Care Unit,” to provide guidance for end-of-life care for the team.148 The Evidence-Based Practice feature on end-of-life care provides a summary of the topics included (Box 11-3). The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Critical Care End-of-Life Peer Workgroup71 identified seven end-of-life care domains for use in the critical care unit:

1. Patient- and family-centered decision making

4. Emotional and practical support

Individuals149 and groups150,151,152 have developed websites for online tools to improve end-of-life care. Critical care unit staff will be able to assess the quality of their care by assessing perceptions of families and staff, auditing documentation,153 or making observations of care. The same attention should be placed on improving end-of-life care that is placed on skills of electrocardiogram interpretation or hemodynamic monitoring.

Summary

• End-of-life care requires knowledge and skill, similar to any other aspect of critical care unit care.

• Patient- and family-centered decision making is key.

• Communication skills are enhanced with additional training in end-of-life conversations.

• Family presence during procedures or resuscitative attempts should be coupled with staff support.

• Extended visiting times are needed to help family members say good-bye.

• Proactive control of symptoms is vital for the patient’s comfort.