Emerging Infectious Diseases

After reading this chapter, the student will be able to:

• Explain the difference between newly emerging and reemerging infectious diseases in the United States and worldwide

• Describe the main factors responsible for the emergence of new infectious diseases

• Discuss the factors involved in the reemerging of infectious diseases that have previously been under control

• Describe how emerging infectious diseases can be divided into four groups based on the process of emergence

• Name and briefly describe the classification of emerging and reemerging infectious diseases set by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

• Explain how to address and prevent emerging infectious diseases

• Discuss the global concerns relating to emerging and reemerging infectious diseases

• Describe the role of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in protecting U.S. citizens from emerging infectious diseases

• Discuss the importance of global surveillance of infectious diseases

• Name and describe five infectious diseases that have emerged or reemerged between 1980 and the present

Emerging/Reemerging Infectious Diseases

1. The introduction of the pathogen into a new host population, and

2. The establishment and further spreading of the pathogen within the new host population, a process referred to as adoption.

Factors of Emergence/Reemergence

Human Demographics and Behavior

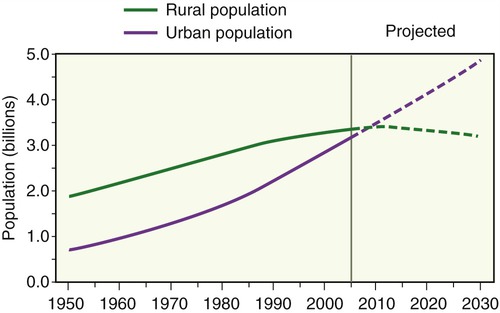

Changes in human demographics due to migration or war are often significant factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Population movements are often due to economic conditions, which encourage workers to move from rural areas into cities. Beginning in the twentieth century a rapid urbanization of the world’s population occurred: whereas in 1950, 29% of the population lived in urban areas, the United Nations estimates that in 2030 approximately 60% will live in urban areas, increasing to more than 69% by the year 2050 (Figure 18.1 and Table 18.1). The population density in urban areas makes disease transmission easier as it allows infections that arise in isolated rural areas that previously remained vague and localized, to reach the larger urban population. Once in the city, the disease not only spreads locally, but can also spread farther by intraurban transport routes, along highways, and by airplane.

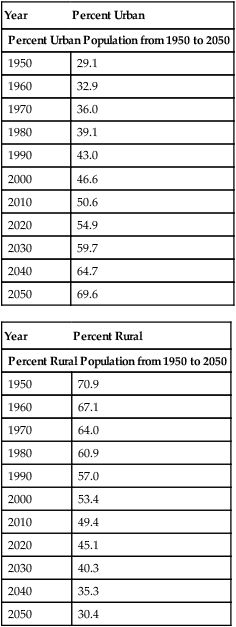

TABLE 18.1

Urban and Rural Population Percentages from 1950 to 2050

| Year | Percent Urban |

| Percent Urban Population from 1950 to 2050 | |

| 1950 | 29.1 |

| 1960 | 32.9 |

| 1970 | 36.0 |

| 1980 | 39.1 |

| 1990 | 43.0 |

| 2000 | 46.6 |

| 2010 | 50.6 |

| 2020 | 54.9 |

| 2030 | 59.7 |

| 2040 | 64.7 |

| 2050 | 69.6 |

| Year | Percent Rural |

| Percent Rural Population from 1950 to 2050 | |

| 1950 | 70.9 |

| 1960 | 67.1 |

| 1970 | 64.0 |

| 1980 | 60.9 |

| 1990 | 57.0 |

| 2000 | 53.4 |

| 2010 | 49.4 |

| 2020 | 45.1 |

| 2030 | 40.3 |

| 2040 | 35.3 |

| 2050 | 30.4 |

Microbial Adaptation and Change

Antimicrobial resistance (see Chapter 22, Antimicrobial Drugs) due to the overuse of antimicrobial drugs and the failure to ensure proper diagnosis and adherence to treatment has become a significant public health problem. This widespread use of antibiotics and other antimicrobials has resulted in evolutionary adaptations in microbes, enabling them to survive many powerful drugs. Antimicrobial drug–resistant strains are a continuing source of emerging infections and diseases.

Other Factors in Disease Emergence and Reemergence

• Human susceptibility to infection: A compromised immune system due to HIV infection, transplants, cancer treatment, chronic diseases, as well as aging increases the susceptibility to emerging and reemerging disease in individuals.

• Poverty: Malnutrition and poor living conditions also increase susceptibility to all infectious diseases.

• War and famine: Most casualties in modern wars are not soldiers but civilians as a result of the destruction of water supplies, malnutrition, and a collapse of the public healthcare system. All these will help contribute to the emergence and reemergence of infectious disease.

• Climate, weather, and natural disasters: Tsunamis, hurricanes, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and simple changes in weather pattern will force microbes to adapt to the new environment for survival—possibly creating new strains of organisms that are capable of causing a new disease, or the reemergence of old, disease-causing strains.

• Intent to do harm: Bioterrorism and biowarfare agents are covered in Chapter 24 (Microorganisms in the Environment and Environmental Safety)

Types of Emerging and Reemerging Diseases

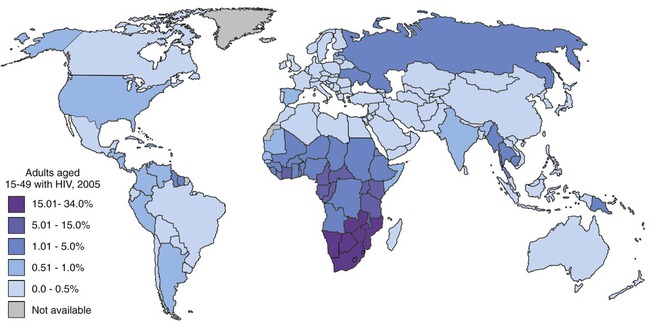

1. Newly emerging diseases that previously have not been known, such as hantavirus, Ebola, and AIDS (Figure 18.2)

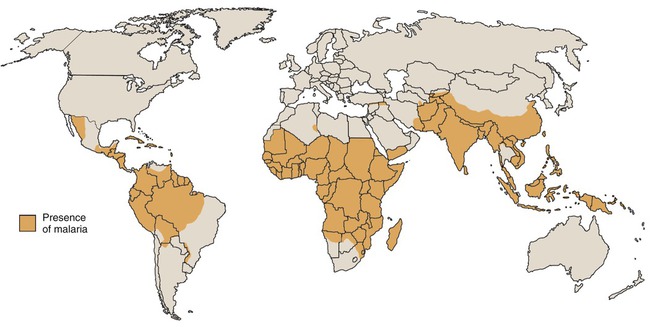

2. Reemerging diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria (Figure 18.3)

3. New manifestations of known disease agents, for example, genital, respiratory, and cardiac manifestations of chlamydia

4. Introduction of known agents into new geographical territories such as the rapid spread of the West Nile virus in the United States

• Group I: Pathogens that have been newly recognized in the past two decades

• Group II: Reemerging pathogens

• Group III: Agents with bioterrorism potential, subdivided into categories A, B, and C (see Chapter 24, Microorganisms in the Environment and Environmental Safety). Only NIAID category A organisms are included in the tables of this chapter

Bacterial, viral, fungal, protozoan, as well as prion-related emerging diseases are included in these groups (Tables 18.2 through 18.5). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, Atlanta, GA), almost 70% of emerging infectious disease episodes in the last decade or more have been zoonotic diseases. The recurrent examples of infections originating as zoonoses suggest that this reservoir of infections is a potentially rich source of emerging diseases and the periodic appearance of new zoonoses indicates that this pool is not exhausted. Although zoonotic agents generally do not spread easily from person to person, other factors, as discussed previously, might help to transmit the infection.

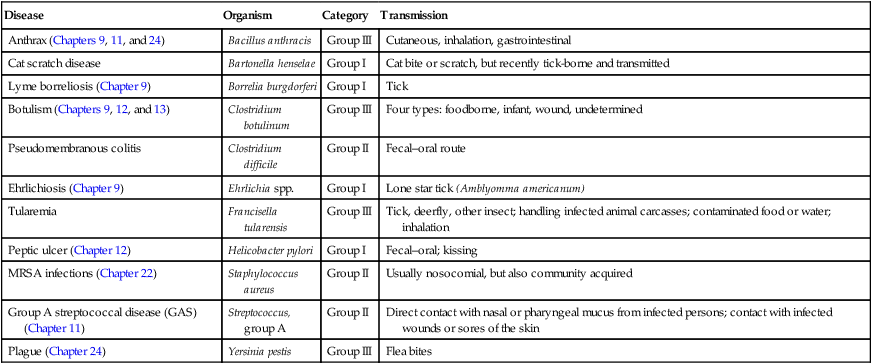

TABLE 18.2

Bacterial Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases

| Disease | Organism | Category | Transmission |

| Anthrax (Chapters 9, 11, and 24) | Bacillus anthracis | Group III | Cutaneous, inhalation, gastrointestinal |

| Cat scratch disease | Bartonella henselae | Group I | Cat bite or scratch, but recently tick-borne and transmitted |

| Lyme borreliosis (Chapter 9) | Borrelia burgdorferi | Group I | Tick |

| Botulism (Chapters 9, 12, and 13) | Clostridium botulinum | Group III | Four types: foodborne, infant, wound, undetermined |

| Pseudomembranous colitis | Clostridium difficile | Group II | Fecal–oral route |

| Ehrlichiosis (Chapter 9) | Ehrlichia spp. | Group I | Lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) |

| Tularemia | Francisella tularensis | Group III | Tick, deerfly, other insect; handling infected animal carcasses; contaminated food or water; inhalation |

| Peptic ulcer (Chapter 12) | Helicobacter pylori | Group I | Fecal–oral; kissing |

| MRSA infections (Chapter 22) | Staphylococcus aureus | Group II | Usually nosocomial, but also community acquired |

| Group A streptococcal disease (GAS) (Chapter 11) | Streptococcus, group A | Group II | Direct contact with nasal or pharyngeal mucus from infected persons; contact with infected wounds or sores of the skin |

| Plague (Chapter 24) | Yersinia pestis | Group III | Flea bites |

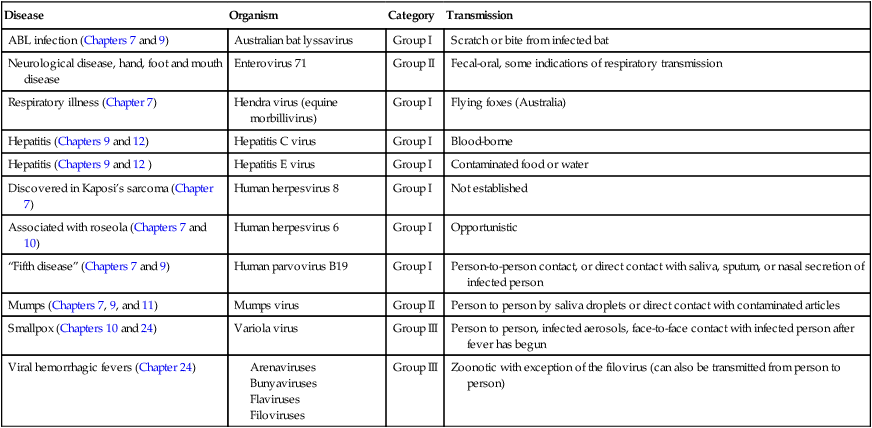

TABLE 18.3

Viral Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases

| Disease | Organism | Category | Transmission |

| ABL infection (Chapters 7 and 9) | Australian bat lyssavirus | Group I | Scratch or bite from infected bat |

| Neurological disease, hand, foot and mouth disease | Enterovirus 71 | Group II | Fecal-oral, some indications of respiratory transmission |

| Respiratory illness (Chapter 7) | Hendra virus (equine morbillivirus) | Group I | Flying foxes (Australia) |

| Hepatitis (Chapters 9 and 12) | Hepatitis C virus | Group I | Blood-borne |

| Hepatitis (Chapters 9 and 12 ) | Hepatitis E virus | Group I | Contaminated food or water |

| Discovered in Kaposi’s sarcoma (Chapter 7) | Human herpesvirus 8 | Group I | Not established |

| Associated with roseola (Chapters 7 and 10) | Human herpesvirus 6 | Group I | Opportunistic |

| “Fifth disease” (Chapters 7 and 9) | Human parvovirus B19 | Group I | Person-to-person contact, or direct contact with saliva, sputum, or nasal secretion of infected person |

| Mumps (Chapters 7, 9, and 11) | Mumps virus | Group II | Person to person by saliva droplets or direct contact with contaminated articles |

| Smallpox (Chapters 10 and 24) | Variola virus | Group III | Person to person, infected aerosols, face-to-face contact with infected person after fever has begun |

| Viral hemorrhagic fevers (Chapter 24) |

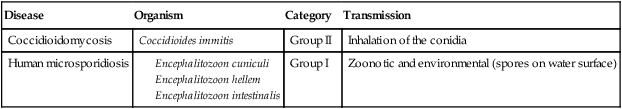

TABLE 18.4

Fungal Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases

| Disease | Organism | Category | Transmission |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Coccidioides immitis | Group II | Inhalation of the conidia |

| Human microsporidiosis | Group I | Zoonotic and environmental (spores on water surface) |

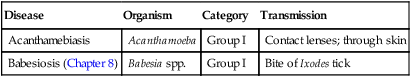

TABLE 18.5

Protozoan Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases

| Disease | Organism | Category | Transmission |

| Acanthamebiasis | Acanthamoeba | Group I | Contact lenses; through skin |

| Babesiosis (Chapter 8) | Babesia spp. | Group I | Bite of Ixodes tick |

Addressing and Preventing Emerging and Reemerging Diseases

Many infectious diseases that occur in the United States are in the category of Nationally Notifiable Diseases (see Box 9-1 in Chapter 9, Infection and Disease). In other words, they need to be reported to the public health system. Numerous other emerging diseases are not yet in this reportable category because of continuous changes and the need for constant updates. General provisions for fighting infectious diseases in the United States include the responsibilities for monitoring, preventing, and controlling infectious disease. These responsibilities are carried out by hospitals, clinical laboratories, pharmaceutical companies, healthcare providers, universities, and various other research groups. Although these are part of a large system working to reduce the impact of pathogenic organisms, it is the CDC that acts as the lead U.S. federal agency responsible for providing information, recommendations, and technical assistance to support state and local public health departments (see Epidemiology and Public Health in Chapter 9, Infection and Disease).

Response

The intervention/prevention/response to emerging diseases will depend on the disease and should be a public health response utilizing a variety of methods. One of the most successful tools in preventing infectious diseases is appropriate immunization programs. The National Immunization Program supports local health departments in planning, developing, and implementing immunization programs (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/). Other measures to prevent or interrupt the transmission process of infectious agents include rodent or insect vector control, food recall, isolation, and quarantine. Because human behavior is an important factor in infectious disease transmission, education and information campaigns are also an essential feature of most disease response activities.

Global Concerns

The National Center for Infectious Diseases (NCID), a branch of the CDC, has now been officially reorganized. The former divisions and programs of the NCID have been reorganized into multiple national centers. The National Center for Preparedness, Detection, and Control of Infectious Diseases (NCPDCID) is now the agency responsible for the protection of domestic and international populations. Through their leadership, partnership, epidemiologic and laboratory studies, and the use of quality systems, this agency establishes standards and practices for response to infectious diseases (http://www.cdc.gov/ncpdcid/).

The International Emerging Infections Program (IEIP) is an integral component of the CDC’s Global Disease Detection Program. This is the agency’s principal program to reinforce the identification of emerging infections around the world, and to effectively respond to them (http://www.cdc.gov/ieip/).

U.S. Global Public Health

• Protecting the health of U.S. citizens at home and abroad by controlling disease outbreaks and also dangerous endemic diseases. Wherever endemic diseases occur, the disease must be prevented from spreading internationally.

• Furthering U.S. humanitarian efforts potentially saves many human lives by preventing infectious diseases overseas. The prevention of many infectious diseases can be achieved by vaccination.

• Providing diplomatic and economic benefits for international projects that address infectious diseases. Improvements in global health will not only enhance the economy but also reduce U.S. healthcare costs by decreasing the number of imported diseases.

• Enhancing security to prevent the intentional release of biological agents by terrorist organizations (see Bioterrorism in Chapter 24, Microorganisms in the Environment and Environmental Safety).

1. International outbreak assistance is considered to be an integral function of the CDC. This needs to include follow-up assistance after each acute emergency response to maintain control of new pathogens after the outbreak.

2. A global approach to disease surveillance needs to evolve into a global “network of networks” to provide early warning of emerging health threats. Such a network also increases the capacity to monitor the effectiveness of public health control measures.

3. Applied research on diseases of global importance, including those that are uncommon in the United States, is a valuable resource because of the dangers represented by certain imported diseases.

4. Applications of proven public health tools need to be identified and shared with the international community.

5. Global initiatives for disease control are needed to reduce the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in young people by 25% and to reduce deaths from tuberculosis and malaria by 50% by the year 2010. To reduce infant mortality the CDC shall work with the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization to enhance delivery and use of new vaccines against respiratory illnesses and other childhood diseases.

6. Public health training through the encouragement and support of the CDC should result in the establishment of International Emerging Infections Programs (IEIPs) in developing countries. These centers of excellence will integrate disease surveillance, applied research, prevention, and control activities.

Global Surveillance

To rapidly identify and contain public health emergencies the world requires a reliable global system. The International Health Regulations (IHR), revised in 2005, provide such a global framework to address these needs through a collective approach for prevention, detection, and timely response to any public health emergency of international concern. Once a communicable disease outbreak has been confirmed, the information is posted on the World Wide Web, and is accessible by healthcare professionals and the general public (http://www.who.int/csr/don/en/). The international response to an outbreak involves a World Health Organization (WHO) team that arrives on site within 24 hours of the information release, for initial assessment and the beginning of immediate control measures. The international response linked to the global surveillance presents a worldwide “network of networks,” available for technical or humanitarian support, ensuring that no one country has to bear the entire burden.

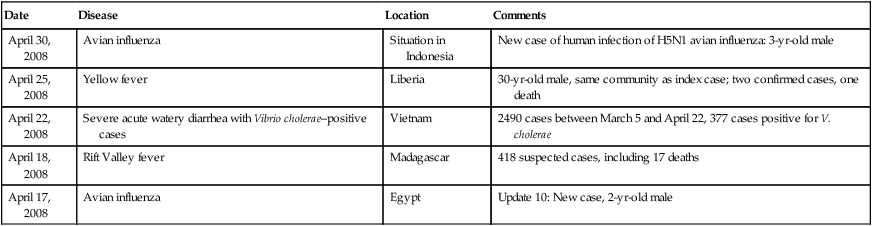

HEALTHCARE APPLICATION

Examples of Epidemic and Pandemic Alert and Response*

| Date | Disease | Location | Comments |

| April 30, 2008 | Avian influenza | Situation in Indonesia | New case of human infection of H5N1 avian influenza: 3-yr-old male |

| April 25, 2008 | Yellow fever | Liberia | 30-yr-old male, same community as index case; two confirmed cases, one death |

| April 22, 2008 | Severe acute watery diarrhea with Vibrio cholerae–positive cases | Vietnam | 2490 cases between March 5 and April 22, 377 cases positive for V. cholerae |

| April 18, 2008 | Rift Valley fever | Madagascar | 418 suspected cases, including 17 deaths |

| April 17, 2008 | Avian influenza | Egypt | Update 10: New case, 2-yr-old male |

*Examples of the cases are reported as soon as information is available. Current updates can be found at http://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/year/2008/en/index.html.

Summary

• Emerging infectious diseases are diseases newly identified in a population; reemerging infectious diseases are known diseases that have previously been under control but are recurring.

• The emergence of infectious diseases generally involves two steps: the introduction of a pathogen into a new host population, and the establishment and further spreading within the new host population, which is referred to as adoption.

• Factors responsible for the emergence of new infectious diseases include human demographics and behavior, ecological changes and agricultural development, international travel and commerce, technology and industry, microbial adaptation and change, breakdown of public health measures, human susceptibility to infection, climate and weather, economic development and land use, war and starvation, and intent to harm.

• Emerging infectious diseases can be divided into four major groups: newly emerging diseases, reemerging diseases, new manifestations of known disease agents, and the introduction of known agents into new geographical territories.

• The NIAID has classified emerging and reemerging infectious diseases as being caused by group I, II, and III pathogens.

• Provisions for fighting infectious diseases in the United States include monitoring, preventing, and controlling infectious disease. The CDC acts as the lead U.S. federal agency responsible for providing information, recommendations, and technical assistance to state and local public health departments.

• Steps in addressing and preventing emerging diseases include surveillance, investigation, and response measures.

• To protect U.S. citizens from infectious disease at home and abroad the United States must participate in combating infectious disease threats around the world.

• The International Emerging Infections Program (IEIP) is an integral component of the CDC’s Global Disease Detection Program.

• The International Health Regulations (IHR) provide a global framework to address prevention, detection, and timely response to any public health emergency of international concern.

Review Questions

1. The establishment and further spreading of an infectious disease within a new population is a process called:

2. The United Nations estimates that by the year 2050 more than __________ of the world’s population will live in urban areas.

3. The Marburg virus was originally spread by:

4. Which of the following infectious diseases is considered a newly emerging disease?

5. Which of the following infectious diseases is considered to be a reemerging disease?

6. Which of the following organisms belongs in the group I category?

7. Which of the following diseases is considered to fall in the group II category?

8. Protozoan emerging and reemerging diseases generally belong to category:

9. Which of the following diseases is transmitted by the fecal–oral route?

10. Which of the following diseases can be transmitted by a tick?

11. Small changes in the viral coat that happen over time are referred to as an antigenic __________.

12. The lead federal agency whose primary responsibility is to protect the people of the United States from infectious diseases is the __________.

13. The Hendra virus is transmitted by __________.

14. “Fifth disease” is caused by __________.

15. Acanthamebiasis is a group __________ emerging/reemerging infectious disease.

16. Define emerging and reemerging infectious diseases.

17. Describe five factors that play a role in the emerging of infectious disease.

18. Describe what type of agent would be placed in group I of emerging and reemerging infectious diseases.

19. Name and briefly describe the six priority areas dealing with global infectious disease.

20. Discuss the role of continuing urbanization in the emerging/reemerging of infectious diseases.