Chapter 61 Emergency Medical Services for Children

The overwhelming majority of the 30 million children who present annually for emergency care in the USA are seen at community hospital emergency departments (EDs). Visits to children’s hospital EDs account for just 11% of initial emergency care encounters. This distribution suggests that the greatest opportunity to optimize care for acutely ill or injured pediatric patients, on a population basis, occurs broadly as part of a systems-based approach to emergency services, an approach that incorporates the unique needs of children at every level. Conceptually, emergency medical services for children (EMSC) are characterized by an integrated, continuum of care model (see Fig. 61-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at ![]() www.expertconsult.com). The model is designed such that patient care flows seamlessly from the primary care medical home through transport and on to hospital-based definitive care. It includes the following 5 principal domains of activity:

www.expertconsult.com). The model is designed such that patient care flows seamlessly from the primary care medical home through transport and on to hospital-based definitive care. It includes the following 5 principal domains of activity:

The Primary Care Physician and Office Preparedness

Staff Training and Continuing Education

Resuscitation Equipment

Availability of necessary equipment is a vital part of an emergency response. Every physician’s office should have essential resuscitation equipment and medications packaged in a pediatric resuscitation cart or kit (Table 61-1). This cart or kit should be checked on a regular basis and kept in an accessible location known to all office staff. Outdated medications, a laryngoscope with a failed light source, or an empty oxygen tank represents a potential catastrophe in a resuscitation setting. Such an incident can be easily avoided if an equipment checklist and maintenance schedule are implemented. A pediatric kit that includes posters, laminated cards, or a color-coded length-based resuscitation tape specifying emergency drug doses and equipment size is invaluable in avoiding critical therapeutic errors during resuscitation.

Table 61-1 RECOMMENDED DRUGS AND EQUIPMENT FOR PEDIATRIC OFFICE EMERGENCIES

| PRIORITY | |

|---|---|

| DRUGS | |

| Oxygen | E |

| Albuterol for inhalation | E |

| Epinephrine (1 : 1,000) | E |

| Activated charcoal | S |

| Antibiotics | S |

| Anticonvulsants (diazepam/lorazepam) | S |

| Corticosteroids (parenteral/oral) | S |

| Dextrose (25%) | S |

| Diphenhydramine (parenteral, 50 mg/mL) | S |

| Epinephrine (1 : 10,000) | S |

| Atropine sulfate (0.1 mg/mL) | S |

| Naloxone (0.4 mg/mL) | S |

| Sodium bicarbonate (4.2%) | S |

| INTRAVENOUS FLUIDS | |

| Normal saline (NS) or lactated Ringer solution (500-mL bags) | S |

| 5% dextrose, 0.45 NS (500-mL bags) | S |

| Equipment for Airway Management | |

| Oxygen and delivery system | E |

| Bag-valve-mask (450-mL and 1,000-mL) | E |

| Clear oxygen masks, breather and non-rebreather, with reservoirs (infant, child, adult) | E |

| Suction device, tonsil tip, bulb syringe | E |

| Nebulizer (or metered-dose inhaler with spacer/mask) | E |

| Oropharyngeal airways (sizes 00-5) | E |

| Pulse oximeter | E |

| Nasopharyngeal airways (sizes 12-30F) | S |

| Magill forceps (pediatric, adult) | S |

| Suction catheters (sizes 5-14F) | S |

| Nasogastric tubes (sizes 6-14F) | S |

| Laryngoscope handle (pediatric, adult) with extra batteries, bulbs | S |

| Laryngoscope blades (straight 0-4; curved 2-3) | S |

| Endotracheal tubes (uncuffed 2.5-5.5; cuffed 6.0-8.0) | S |

| Stylets (pediatric, adult) | S |

| Esophageal intubation detector or end-tidal carbon dioxide detector | S |

| EQUIPMENT FOR VASCULAR ACCESS AND FLUID MANAGEMENT | |

| Butterfly needles (19-25 gauge) | S |

| Catheter-over-needle device (14-24 gauge) | S |

| Arm boards, tape, tourniquet | S |

| Intraosseous needles (16-, 18-gauge) | S |

| Intravenous tubing, micro-drip | S |

| MISCELLANEOUS EQUIPMENT AND SUPPLIES | |

| Color-coded tape or preprinted drug doses | E |

| Cardiac arrest board/backboard | E |

| Sphygmomanometer (infant, child, adult, thigh cuffs) | E |

| Splints, sterile dressings | E |

| Automated external defibrillator with pediatric capabilities | S |

| Spot glucose test | S |

| Stiff neck collars (small/large) | S |

| Heating source (overhead warmer/infrared lamp) | S |

E, essential; S, strongly suggested.

Adapted from American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine; Frush K: Preparation for emergencies in the offices of pediatricians and pediatric primary care providers, Pediatrics 120:200–212, 2007.

Pediatric Prehospital Care

Destination Determination

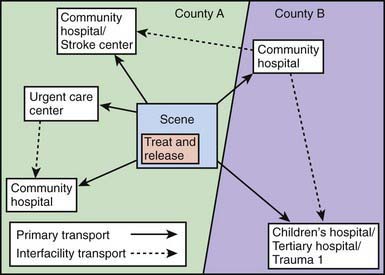

The destination to which a pediatric patient is transported may be defined by parental preference, provider preference, or jurisdictional protocol, which is typically predicated on field assessment of anatomic and physiologic criteria and, in the case of trauma, mechanism of injury. In communities served by an organized trauma or regionalized EMS system that incorporates pediatric designation based on objectively verified hospital capabilities, seriously ill or injured children may be triaged by protocol to the highest-level center reachable within a reasonable amount of time. The mantra is to deliver the child to the “right care in the right time,” even if it requires bypassing closer hospitals. An exception is the child in full arrest, for whom expeditious transport to the nearest facility is always warranted. Regionalization in the context of EMS is defined as a geographically organized system of services that ensures access to care at a level appropriate to patient needs while maintaining efficient use of available resources. This system concept is especially germane in the care of children, given the relative scarcity of facilities capable of managing the full range and scope of pediatric conditions (Fig. 61-2). Regionalized systems of care coordinated with emergency medical dispatch, field triage, and EMS transport have demonstrated efficacy in improving outcomes for pediatric trauma patients, especially for younger children and children with isolated head injury. Emerging evidence also suggests a similar benefit conferred to children in shock identified in the field who are preferentially transported to hospital EDs with documented pediatric ALS capability. The existence of statewide or regional standardized systems that formally recognize hospitals able to stabilize and/or manage pediatric medical emergencies is another federal EMSC performance measure against which operational capacity to provide optimal pediatric emergency care in this country is currently being judged.

In communities that do not have a hospital with the equipment and personnel resources to provide definitive pediatric inpatient care, interfacility transport of a child to a regional center should be undertaken after initial stabilization (Chapter 61.1). When interfacility transport is to be undertaken, indications for transfer, parental consent for transfer, and acceptance of the patient by the receiving physician must all be clearly documented in the medical record.

The Emergency Department

Minimum standards must be met by community EDs to ensure that children receive the best emergency care possible. Updated guidelines for the care of children in the ED have been published and are endorsed by the AAP, the ACEP, and the ENA. These guidelines provide current information on policies, procedures, protocols, quality assurance methods, and equipment and supplies considered essential for managing pediatric emergencies. Specific recommendations on equipment, supplies, and medications for the ED are listed and updates are available on the AAP website. Sample policies, procedures, and protocols specifically addressing the needs of children in the ED are listed in Table 61-2.

Table 61-2 GUIDELINES FOR PEDIATRIC-SPECIFIC POLICIES, PROCEDURES, AND PROTOCOLS FOR THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

Illness and injury triage

Pediatric patient assessment and reassessment

Documentation of pediatric vital signs, abnormal vital signs, and actions to be taken for abnormal vital signs

Immunization assessment and management of the underimmunized patient

Sedation and analgesia for procedures, including medical imaging

Consent (including situations in which a parent is not immediately available)

Social and mental health issues

Physical or chemical restraint of patients

Child maltreatment (physical and sexual abuse, sexual assault, and neglect) mandated reporting criteria, requirements, and processes

Death of the child in the emergency department

Do-not-resuscitate orders

Communication with patient’s medical home or primary health care provider

Medical imaging policies that address age- or weight-appropriate dosing for children receiving studies that impart ionizing radiation, consistent with ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) principles

Adapted from American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine; American College of Emergency Physicians Pediatric Committee; Emergency Nurses Association Pediatric Committee: Joint policy statement—guidelines for care of children in the emergency department, Pediatrics 124:1233–1243, 2009.

Emerging Issues in EMSC

Research

Building the evidence base for pediatric emergency care and EMSC is especially challenging, given the relative infrequency of critical conditions of research interest and need, and the rare occurrence of adverse outcomes. No single medical center or EMS agency is able to generate sufficient sample size to conduct scientifically rigorous controlled studies, let alone randomized trials, of emergency pediatric problems. In 2001, the Health Resources and Services Administration announced a competitive research funding opportunity, entitled the EMSC Network Development Demonstration Project (NDDP). The NDDP funding stream has supported a now mature national research network known as the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN), which accounts for more than 800,000 ED visits of children distributed among nearly two dozen sites around the country. The PECARN is exploring some of the most vexing questions in pediatric emergency care and challenging practice dogma by leveraging the strength of its number of potential subject enrollees in randomized, controlled trials. According to the specific IOM recommendation, the National Resource Center (NRC) of the EMSC program has generated a comprehensive Gap Analysis of EMS Related Research, which can be accessed electronically from the EMSC NRC website, www.childrensnational.org/EMSC.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Emergency MedicineAmerican College of Emergency Physicians Pediatric CommitteeO’Malley PJ, Brown K, Krug SE. Patient and family-centered care and the role of the emergency physician providing care to a child in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:643-645.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency MedicineAmerican College of Emergency Physicians Pediatric CommitteeEmergency Nurses Association Pediatric CommitteeGausche-Hill M, Krug SE. Joint policy statement—guidelines for care of children in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1233-1243.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency MedicineFrush K, Krug SE. Patient safety in the pediatric emergency care setting. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1367-1375.

American Academy of PediatricsCommittee on Pediatric Emergency MedicineFrush K. Preparation for emergencies in the offices of pediatricians and pediatric primary care providers. Pediatrics. 2007;120:200-212.

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on OrthopaedicsAmerican Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency MedicineAmerican Academy of Pediatrics Section on Critical Care; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on SurgeryAmerican Academy of Pediatrics Section on Transport MedicineAmerican Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency MedicinePediatric Orthopaedic Society of North AmericaTuggle D, Krug SE. Management of pediatric trauma. Pediatrics. 2008;121:849-854.

American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, American College of Emergency Physicians, National Association of EMS Physicians, Pediatric Equipment Guidelines Committee—Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) Partnership for Children Stakeholder Group, American Academy of Pediatrics. Equipment for ambulances. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e166-e171.

Ball JW, Liao E, Kavanaugh D, et al. The emergency medical services for children program: accomplishments and contributions. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2006;7:6-14.

Burt CW, Middleton KR. Factors associated with ability to treat pediatric emergencies in US hospitals. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:681-689.

Carcillo J, Kuch B, Han Y, et al. Use of PALS/APLS by community physicians to reverse all-cause pediatric shock is associated with reduced mortality and functional morbidity: a multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;124:500-508.

Cichon M, Lyons E, Fuchs S, et al. A statewide model program to improve emergency department readiness for pediatric care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:198-204.

Committee on Pediatric Emergency MedicineKrug SE, Frush K. Patient safety in the pediatric emergency care setting. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1367-1375.

EMSC National Resource Center. EMSC performance measures: 2007 edition. Implementation manual for state partnership grantees. EMSC National Resource Center, Washington, DC, 2007. http://bolivia.hrsa.gov/emsc/PerformanceMeasures/PerformanceMeasuresComplete.htm. Accessed July 13, 2009

EMSC National Resource Center, Children’s National Medical Center. Gap analysis of EMS related research: report to the Federal Interagency Committee on EMS (website). www.childrensnational.org/emsc. Accessed March 17, 2010

Gausche-Hill M, Schmitz C, Lewis RJ. Pediatric preparedness of United States emergency departments: a 2003 survey. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1229-1237.

Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the US Health System. Emergency care for children: growing pains. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the US Health System. Emergency medical services: at the crossroads. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the US Health System. Hospital-based emergency care: at the breaking point. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

Institute of Medicine, Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medical Services. Durch JS, Lohr KN, editors. Institute of Medicine report: emergency medical services for children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1993.

Junkins E, O’Connell J, Mann N. Pediatric trauma systems in the United States: do they make a difference? Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2006;7:76-81.

National Commission on Children and Disasters: 2010 Report to the President and Congress, AHRQ Pub No 10-M037, Rockville, MD, October 2010, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.ahrq.gov/prep/nccdreport. Accessed November 16, 2010.

Sirbaugh PE, Gurwitch KD, Macias CG, et al. Caring for evacuated children housed in the Astrodome: creation and implementation of a mobile pediatric emergency response team: regionalized caring for displaced children after a disaster. Pediatrics. 2006;117:S428-S438.

Toback S, Fiedor M, Kilpela B, et al. Impact of a pediatric primary care office-based mock code program on physician and staff confidence to perform life-saving skills. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:415-422.

Wright J. Emergency medical services for children and the Institute of Medicine revisited, 1993–2006. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2006;7:69-70.

61.1 Interfacility Transport of the Seriously Ill or Injured Pediatric Patient*

Ajizian SJ, Nakagawa TA. Interfacility transport of the critically ill pediatric patient. Chest. 2007;132:1361-1367.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Transport Medicine. Woodward GA, Insoft RM, Kleinman ME, editors. Air and ground transport of neonatal and pediatric patients. Chicago: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2007.

Institute of Medicine Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Emergency care for children: growing pains. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007.

King BR, King TM, Foster RL, et al. Pediatric and neonatal transport teams with and without a physician: a comparison of outcomes and interventions. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:77-82.

King BR, Woodward GA. Pediatric critical care transport: the safety of the journey; a five-year review of vehicular collisions involving pediatric and neonatal transport teams. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;6:449-454.

McCloskey KA, King WD, Byron L. Pediatric critical care transport: is a physician always needed on the team? Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:961-966.

Nieman CT, Merlino JI, Kovach B, et al. Intubated pediatric patients requiring transport: a review of patients, indications, and standards. Air Med J. 2001;21:22-25.

Philpot C, Day S, Marcdante K, et al. Pediatric interhospital transport: diagnostic discordance and hospital mortality. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:15-19.

Woodward GA, Insoft RM, Pearson-Shaver AL, et al. The state of pediatric interfacility transport: consensus of the second national pediatric and neonatal interfacility transport medicine leadership conference. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:38-43.

61.2 Outcomes and Risk Adjustment

Risk Adjustment Tools in EMSC

Pediatric Risk of Admission II

PRISA II uses components of acute and chronic medical history and physiology to determine the probability of hospitalization. The outcome measure of interest is mandatory hospital admission (admissions utilizing therapies best delivered on an inpatient basis). The patient-related attributes contributing to the PRISA II risk-adjustment score are listed in Table 61-3. Analytic models including the PRISA II score had good calibration (how well the probabilities predicted from the model correlated with the observed outcomes in the population) and discrimination (the ability to categorize subjects correctly into the categories of interest) with respect to mandatory hospital admission. Construct validity of the PRISA score was demonstrated by measuring the rates of the secondary outcomes: mandatory admission, PICU admission, and mortality. As the probability of hospital admission rose, the proportion of patients with these increasing care requirements also increased. This finding strongly supports the use of the PRISA II score as a valid measure of severity of illness. In addition, PRISA II was used to demonstrate racial/ethnic differences in severity-adjusted hospitalization rates, and also demonstrated that teaching hospitals had higher than expected severity-adjusted admission rates in comparison with non-teaching hospitals.

Revised Pediatric Emergency Assessment Tool

The Revised Pediatric Emergency Assessment Tool uses a limited set of data collected at the time of triage to model severity of illness as reflected by the level of care provided in the ED. This tool was developed to predict the level of care provided—routine assessment (clinical examination only ± nonprescription medicine), specific ED care (ED diagnostics and/or therapeutics), or hospital admission—with the implicit assumption that patients with a higher level of care have a higher severity of illness. The patient-related attributes contributing to the RePEAT risk-adjustment score are listed in Table 61-4. As with PRISA II, analytic models including the RePEAT score had good calibration and discrimination with respect to predicting ED care and hospital admission. Furthermore, analytic models that compare costs and ED length of stay between EDs are improved by adjustment for severity of illness using the RePEAT score. These results demonstrate that RePEAT is a reasonable marker of severity of illness and that inclusion of this severity index substantially improves the ability to compare outcomes between EDs.

Chamberlain JM, Joseph JG, Pollack MM. Differences in severity-adjusted pediatric hospitalization rates are associated with race/ethnicity. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1319-e1324.

Chamberlain JM, Patel KM, Pollack MM. The pediatric risk of hospital admission score: a second-generation severity-of-illness score for pediatric emergency patients. Pediatrics. 2005;115:388-395.

Chamberlain JM, Patel KM, Pollack MM. The association of emergency department care factors with admission and discharge decisions for pediatric patients. J Pediatr. 2006;149:644-649.

Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260:1743-1748.

Gorelick MH, Alessandrini EA, Cronan K, et al. Revised pediatric emergency assessment tool (RePEAT): a severity index for pediatric emergency care. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:316-323.

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

Institute of Medicine. The future of emergency care in the United States health system. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

Institute of Medicine. To err is human: building a safer health care system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system: risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991;100:1619-1636.

MacKenzie EJ. Injury severity scales: overview and directions for future research. Am J Emerg Med. 1984;2:537-549.

Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE. PRISM III: an updated pediatric risk of mortality score. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:743-752.

61.3 Principles Applicable to the Developing World

International pediatric emergency medicine, or IPEM, is an emerging academic field whose practitioners are committed to international collaboration aimed at improving the quality of care for children outside their national borders (see Tables 61-5 and 61-6 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at ![]() www.expertconsult.com).

www.expertconsult.com).

Table 61-5 PEDIATRIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE (PEM) PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

| Australia, New Zealand | |

| PEM Section, Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) | Canada |

| France | |

| PEM Section, Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) | Canada |

| Israel | |

| Italy | |

| Mexico | |

| Spain | |

| Turkey | |

| Europe | |

| USA | |

| USA | |

| USA |

Table 61-6 PEDIATRIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE RESEARCH COLLABORATIVES

| PREDICT: Paediatric Research in Emergency Departments International Collaborative | Australia, New Zealand | www.pems.org.au |

| PERC: Pediatric Emergency Research Canada | Canada | www.perc-canada.ca |

| PECARN: Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network | USA | www.pecarn.org |

| PEM-CRC: Collaborative Research Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics | USA | www.aap.org/sections/PEM/pemcrc.htm |

| REPEDS: Research in European Paediatric Emergency Departments | Belgium, France, Great Britain, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Northern Ireland, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Sweden, Turkey | www.pemdatabase.org/REPEM |

Applying the Continuum of Care Model to the Developing World

Prevention

Injuries

For reducing drowning deaths, strategies that have proven effective focus on creating barriers between children and water hazards, such as covering wells, buckets, and other standing sources of water, and placing high fences around pools (Chapter 67). Burns have been addressed by advocating for installation of smoke detectors and lowering the temperature of water from water heaters (Chapter 68).

Out-of-Hospital Care

Prehospital Care

Around the world, the effort to establish standardized approaches to prehospital care exists primarily in the form of courses to educate EMS and hospital personnel in the emergency management of patients. For trauma care, the WHO manuals Prehospital Trauma Care Systems and Guidelines for Essential Trauma Care both focus on guidelines for prehospital and trauma care systems that are affordable and sustainable. The AAP course Pediatric Education for Prehospital Professionals (PEPP) is a dynamic, modularized teaching tool designed to provide specific pediatric prehospital education that can be adapted to any EMS system. Table 61-7 lists additional prehospital resources.

| Prehospital | |

| Hospital care | |

| Humanitarian emergencies | |

| Access to academic publications relevant to PEM | |

| Involvement | |

| Health organizations involved in international PEM activities | |

Improvement in Quality of Care

In many locations, low-resource interventions are the easiest to provide and can often make large differences in the quality of care offered by any given practitioner or health care center. A long-term goal should be the establishment of ongoing quality assessment and critical incident monitoring. International PEM development should incorporate all stakeholders in the delivery of emergency care in a given catchment area. This effort may include consumers, public health and government officials, and health care officers and practitioners. One may also make use of relationships with local and foreign universities, professional organizations (see Table 61-5), and governmental and nongovernmental organizations.

Promotion of the Emergency Medicine Model

Research Support and Training

Several examples of inter-institutional international research collaborations could serve as models for facilities in the developing world (see Table 61-6). Researchers can assist with developing low-cost mechanisms for data collection and database management. Additionally, training in the importance of utilizing evidence-based practices and appropriate research design can be useful.

Duke T, Kelly J, Weber M, et al. Hospital care for children in developing countries: clinical guidelines and the need for evidence. J Trop Pediatr. 2006;52:1-2.

HINARI Access to Research Initiative. About HINARI (website). http://www.who.int/hinari/about/en. Accessed March 20, 2009

International Federation of Emergency Medicine. About IFEM (website). http://www.ifem.cc/about/about.htm. Accessed April 2, 2009

Khan AN, Rubin DH. International pediatric emergency care: establishment of a new specialty in a developing country. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19:181-184.

Molyneux E. Emergency care for children in resource-constrained countries. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:11-15.

Molyneux E, Ahmad S, Roberston A. Improved triage and emergency care for children reduces inpatient mortality in a resource-constrained setting. Bull World Health Org. 2006;84:314-319.

Moss WJ, Ramakrishnan M, Storms D, et al. Child health in complex emergencies. Bull World Health Org. 2006;84:58-64.

Nolan T, Angos P, Cunha AJLA, et al. Quality of hospital care for seriously ill children in less-developed countries. Lancet. 2001;357:106-110.

Norton R, Hyder AA, Bishai D, et al. Unintentional injuries. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al, editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries. ed 2. New York: Oxford University Press and the World Bank; 2006:737-753. This book can be downloaded from www.dcp2.org/pubs

Peden M, Oyegbite K, Ozannr-Smith J, et al, editors. World report on child injury prevention. Geneva: WHO Press, 2009. This report can be downloaded from www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/child/injury/world_report/en/index.html

Siddiqui EU, Razzak JA. Pediatric emergency medicine—an evolving sub-speciality in Pakistan. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18:135-136.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Progress for children: a world fit for children statistical review, No. 6. New York: UNICEF; 2007. This booklet can be downloaded from www.unicef.org/publications/index.html

United States Agency for International Development. The first modern pediatric ER in the region opens in Georgia (website). www.usaid.gov/stories/georgia/ss_ge_er.html. Accessed March 20, 2009

Walker DM, Tolentino VR, Teach SJ. Trends and challenges in international pediatric emergency medicine. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19:247-252.

World Health Organization (WHO). Emergency triage assessment and treatment (ETAT): manual for participants. Geneva: WHO Press; 2005. This manual is available for download from www.who.int/child_adolescent_health/documents/9241546875/en/index.html

World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for essential trauma care. Geneva: WHO Press; 2004. This book can be downloaded from www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/services/guidelines_traumacare/en/index.html

World Health Organization (WHO). Integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI). Geneva: WHO Press; 2007. This book can be downloaded from www.who.int/child_adolescent_health/topics/prevention_care/child/imci/en/index.html

World Health Organization (WHO). Prehospital trauma care systems. Geneva: WHO Press; 2005. This book can be downloaded from www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/services/39162_oms_new.pdf