CHAPTER 19 EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT THORACOTOMY

Emergency department thoracotomy (EDT) remains a formidable tool within the trauma surgeon’s armamentarium. Since its introduction during the 1960s, the use of this procedure has ranged from sparing to liberal.1 At many urban trauma centers, this procedure has found a niche as part of the resuscitative process.1 Because of improvements in emergency medical services systems (EMS), many critically injured patients now arrive in extremis prompting trauma surgeons to perform this procedure to attempt saving their lives. This technically complex procedure should only be performed by surgeons familiar with the management of penetrating cardiothoracic injuries.

Indications for the use of EDT appearing in the literature range from vague to quite specific.1 It has been used in a variety of settings including penetrating and blunt thoracic and/or thoracoabdominal injuries, cardiac and exsanguinating abdominal vascular injuries.1–4 It has also been used rarely in exsanguinating peripheral vascular injuries arriving in cardiopulmonary arrest and also in pediatric trauma. Many studies in the literature have also reported its use in patients presenting in cardiopulmonary arrest secondary to blunt trauma.

HISTORIC PERSPECTIVE

In 1874, Schift5 was first to promote the concept of open cardiac massage. Rehn6 in 1896 reported the first successful repair of a cardiac injury, a stab wound of the right ventricle. In 1897, Duval7 described the median sternotomy incision widely used today. Igelsbrud5 in 1901 was the first to report successful resuscitation of a patient, sustaining a post-traumatic cardiac arrest patient with a thoracotomy and open cardiac massage. Spangaro8 in 1906 described the left anterolateral thoracotomy widely used today for resuscitation as an intercostocondral thoracotomy.

Zolls5 in 1956 was the first to introduce the concept of external defibrillation, and Kouwenhoven5 in 1960 described closed cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Beall9 et al. in 1961 was the first to propose that patients experiencing cessation of cardiac action should undergo immediate resuscitative thoracotomy and cardiac massage, whether in the ED, operating room (OR), or recovery ward, and was first to attempt this procedure. Similarly, in 1966, he advocated the use of immediate cardiorrhaphy in the emergency room and setting up an instrument tray; he was also the first to successfully perform this procedure.10

OBJECTIVES

Objectives of the EDT procedure include the following:

Cross-clamp the pulmonary hilum and aspirate both the right and left ventricles to prevent and/or treat pulmonary embolism

Cross-clamp the pulmonary hilum and aspirate both the right and left ventricles to prevent and/or treat pulmonary embolismPHYSIOLOGY

Positive Effects

INDICATIONS

Indications for EDT can be subdivided into three categories: accepted, selective, and rare.1–4

Selective Indications

EDT should be performed selectively in patients sustaining exsanguinating abdominal vascular injuries due to its very low survival rate. Meticulous selection of patients should be exercised. This procedure should be used as an adjunct to definitive repair of abdominal vascular injuries.

TECHNIQUES FOR CARDIAC INJURY REPAIR

Incisions

There are two main incisions that are used in the management of penetrating cardiac injuries. Trauma surgeons should be aware that injuries caused by missiles can be unpredictable in their trajectory and that a missile injury that penetrates a hemithoracic cavity may not remain confined in the original area of entrance and may produce injury to the contralateral cavity. This will require the trauma surgeon to access the contralateral hemithoracic cavity.67,68,70,74,77

Median sternotomy described by Duval37 is the incision of choice for patients admitted with penetrating precordial injuries that arrive with some degree of hemodynamic instability and may either undergo preoperative investigation with FAST and/or chest x-ray. It is also the incision of choice or those that are thought to harbor occult cardiac injuries. The left anterolateral thoracotomy is the incision of choice in the management of patients who arrive in extremis. This incision is used in the ED for resuscitative purposes.67,68,70,74,77

The left anterolateral thoracotomy described by Spangaro41 can also be extended across the sternum as bilateral anterolateral thoracotomies, if it is determined during the resuscitative period that the patient’s injury extends into the right hemithoracic cavity (Table 1). Extension into bilateral anterolateral thoracotomies is also is the incision of choice for patients that are hemodynamically unstable after incurring mediastinal traversing injuries. This incision allows full exposure of the anterior mediastinum and pericardium as well as both hemithoracic cavities. It is important to note that upon transection of the sternum both internal mammary arteries are also transected and must be ligated after restoration of perfusion pressure. Uncontrolled, they can serve as a significant source of blood loss. This is a frequent pitfall during the institution of damage control; as trauma surgeons may forget to ligate these vessels prompting return to the operating room for a patient that can ill afford it. For patients that sustain thoracoabdominal injuries, the left anterolateral thoracotomy is also the incision of choice if patients deteriorate in the OR while undergoing a laparotomy.67,68,70,74,77

| Operator | Well-trained surgeon |

| Initial assessment and resuscitation | Endotracheal intubation |

| Immediate venous access | |

| Rapid infusion | |

| Position | Supine with left arm elevated |

| Incision | Left anterolateral incision |

| Fifth intercostal space from left sternocostal junction to latissimus dorsi m. | |

| Procedure | Incision as above |

| Sharp transection of intercostal m. | |

| Open pleura | |

| Place a Finnochietto retractor | |

| Open cardiac massage | |

| Elevate left lung medially | |

| Locate and dissect descending aorta | |

| Cross clamp aorta by Crafoord-Debakey clamp | |

| If cardiac injury (bluish and tense pericardium) | Open pericardium longitudinally with preserving phrenic n. |

| Evacuate blood clot | |

| Repair cardiac injury (mattress sutures of Halsted with Prolene 2/0) | |

| If active bleeding at pulmonary hilum | Cross-clamp pulmonary hilum with Crafoord-Debakey clamp |

| If pulmonary parenchymal laceration | Clamp with Duval clamp |

| If associated injury in contralateral thoracic cavity | Extend incision to the contralateral side |

| Transect sternum sharply | |

| Convert to bilateral anterolateral thoracotomy | |

| If air embolism is suspected (air in coronary v) | Aspirate left ventricle |

| Miscellaneous | Ligate internal mammary a. |

| Systemic or intraventricular epinephrine administration | |

| Internal defibrillation 10–50 joules | |

| Temporary pacemaker | |

| Immediately transport to operating room after successful resuscitation | |

Adjunct Maneuvers

Trauma surgeons must possess several maneuvers in their armamentarium to deal with penetrating cardiothoracic injuries. The first adjunct maneuver dealing with these injuries was described by Sauerbuch42 in 1907, as quoted by Brantigan. This maneuver entailed controlling blood flow to the heart by compression of the base. This maneuver is difficult to perform via a left anterolateral thoracotomy, has been abandoned, and is only mentioned because of historical interest only.

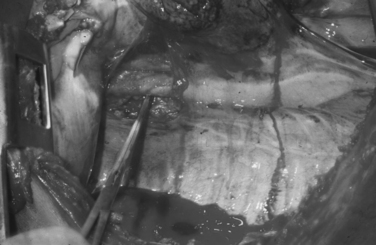

Total inflow occlusion to the heart is a complex maneuver that entails cross-clamping both the superior (SVC) and inferior vena cava (IVC) in their intrapericardial location to arrest total blood flow to the heart. Crafoord-DeBakey cross-clamps are employed, resulting in the immediate emptying of the heart. The trauma surgeon must recognize that cross-clamping the inferior vena cava intrapericardially at the space of Gibbons can be quite treacherous, as it is often fused with the posterior aspect of the pericardium. Inexperienced trauma surgeons will often force the cross-clamp in an attempt to rapidly achieve total occlusion leading to an iatrogenic injury of the intrapericardial IVC. Similarly, circumferentially dissecting this delicate vessel can also lead to iatrogenic injury. The clamp must be placed carefully and sometimes at an angle so as to totally occlude the intrapericardial IVC.70,77

Total inflow occlusion of the heart is indicated for the management of injuries in the lateral-most aspect of the right atrium and/or the superior or inferior atriocaval junction. Total inflow occlusion will lead to immediate emptying of the heart and allow the injury to be visualized and thus repaired. Frequently this procedure results in cardiopulmonary arrest, as tolerance by the injured, acidotic, hypothermic and ischemic heart is very limited. The safe period for this maneuver is unknown, although a 1–3 minute range is often quoted in the literature as the period of time after which clamps must be released. As the clamps are released, venous return fills the right-sided cardiac chambers and forward cardiac pumping motion will begin. More often than not, the heart will fibrillate requiring immediate direct defibrillation along with pharmacologic manipulation. This may be unsuccessful, particularly if a period of 3 minutes has been exceeded. Restoration of a normal sinus rhythm is often impossible.70,77

Cross-clamping of the pulmonary hilum is another valuable maneuver indicated for the management of associated pulmonary injuries, particularly those that have hilar central hematomas and/or active bleeding. This maneuver arrests bleeding from the lung and prevents air emboli from reaching the systemic circulation. However, one of its negative effects is responsible for significantly increasing the afterload of the right ventricle, as half of the pulmonary circulation is no longer available for perfusion. We recommend sequential de-clamping of the hilum to be carried out as expediently as possible along with a direct approach by stapled pulmonary tractotomy70,74 for identification and control of hemorrhaging intraparenchymal pulmonary vessels. This will promptly unload the right ventricle. In the presence of acidosis, hypothermia, and ischemia, the right ventricle may not be able to tolerate this maneuver leading to fibrillation and arrest.70,74

Grabowski1 recently described a maneuver to facilitate exposure of posterior cardiac wounds by placing a Satinsky clamp at the right ventricular angle, which is formed at the acute anteroinferior margin of the right ventricle as it reflects on the right diaphragm. Grabowski1 recommends that the clamp only grasp a small portion of the right ventricle. He recommends this maneuver for elevating the heart out of the pericardium to repair posterior injuries. We have no experience with this maneuver and cannot recommend it. We strongly feel that if used inappropriately, it will lead to the development of significant cardiac dysrhythmias.70,74

Maneuvers such as venting either the right or left ventricle postcardiorrhaphy are recommended to provide an avenue of egress for air emboli trapped in these chambers. This is usually accomplished by placing 16-gauge intravenous catheters. Theoretically, air should eject out of the repair chambers, thus preventing air emboli. Although the authors have used this maneuver successfully, little has been written in the literature describing its outcome.70,74

At times a trauma surgeon will need to elevate the heart out of the pericardium in order to repair certain injuries. Rapid and injudicious manipulation of the heart will often result in complex dysrhythmias that might include ventricular fibrillation and even cardiopulmonary arrest. Occasionally, given the degree of exsanguinating hemorrhage the heart must be extracted rapidly from pericardium in order to perform cardiorrhaphy. The trauma surgeon must communicate with the anesthesiologists whenever this maneuver is performed. If hemorrhage can be digitally controlled, gradual elevation of the heart by placing multiple laparotomy packs will allow better tolerance of this maneuver while decreasing the chances for the development of dysrhythmias.70,74

Waterworth11 recently reported the first case in which the Octopus IV Mechanical Cardiac Stabilizer was used on a 20-year-old patient who sustained a 2-cm stab wound in the right ventricular outflow tract approximately 1 cm below the pulmonary valve. According to the author, this area was difficult to suture without causing further tearing due to tachycardia sustained by the patient and the fragile nature of this area. After control of hemorrhage by direct pressure, the Octopus IV Mechanical Cardiac Stabilizer was placed, which provided for immobility to this area of the heart and thus facilitated repair. In this case report, the author describes the use of this device, suggesting that cardiac stabilization devices with adjustable suction foot blades may be used to control hemorrhage in addition to facilitating repair, particularly in areas difficult or dangerous to handle manually. The recommended positioning parallel to the direction of the wound and approximating the foot plates may result in closure of the wound, providing a clear field for repair. This case report by Waterworth11 appears to be the first and only case reported in the literature utilizing a mechanical cardiac stabilizer in the management of a penetrating cardiac injury. Whether stabilizers will be routinely used in the management of penetrating cardiac injuries in the future remains to be seen.

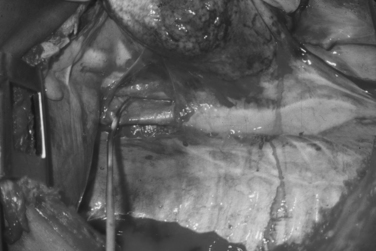

Repair of Atrial Injuries

Atrial injuries can usually be controlled by placement of a Satinsky partial occlusion vascular clamp. Control of the wound will allow the trauma surgeon to perform cardiorrhaphy. We recommend utilizing 2-0 or 3-0 polypropylene monofilament sutures on an MH needle in a running or interrupted fashion. It is important to visualize both sides of the atrial injury, particularly those caused by missiles. Missile injuries can usually cause a significant amount of tissue destruction, which might require meticulous debridement prior to closure. Similarly, a portion of the atria may be resected and cardiorrhaphy performed utilizing a running suture of 2-0 or 3-0 polypropylene monofilament suture. The trauma surgeon must be aware that the atria have fairly thin walls and demand gentleness during cardiorrhaphy, as they can easily tear and enlarge the original injury. The use of bioprosthetic materials in the form of Teflon pledgets is not recommended for management of these injuries.70,74

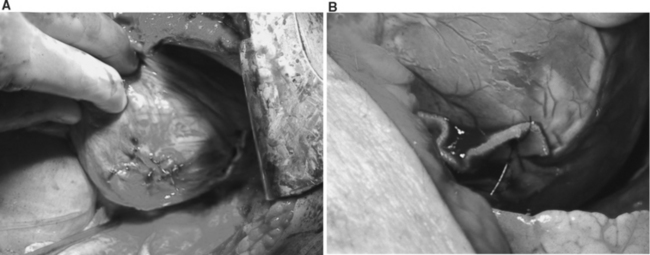

Repair of Ventricular Injuries

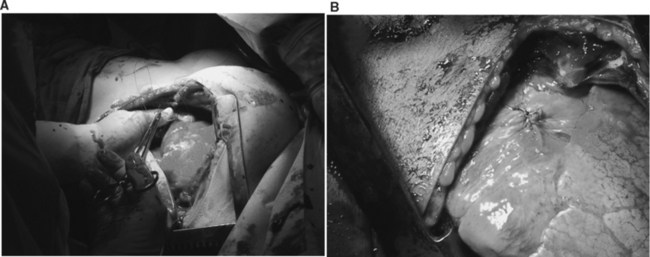

Ventricular injuries usually cause significant hemorrhage. They should be occluded digitally while simultaneously repaired by either simple interrupted or horizontal mattress sutures of Halsted. Ventricular cardiorrhaphy can also be accomplished with a running monofilament suture of 2-0 polypropylene on an MH needle. Performing cardiorrhaphy for ventricular for stab wounds is usually less challenging than for gunshot wounds. Missile injuries often produce some degree of blast effect that causes myocardial fibers to retract. Frequently, missile injuries that have been successfully sutured and controlled enlarge, as the damaged myocardium retracts and becomes more friable. Frequently, these injuries require multiple sutures to control significant hemorrhage. In the presence of this scenario, bioprosthetic materials such as Teflon strips and/or pledgets are often needed to buttress the suture line. This is usually performed by fashioning a Teflon strip that may measure anywhere from 1 to 5 cm (Figure 4A and B). This strip is held by two straight Crile clamps held by an assistant. Simultaneously, the trauma surgeon may then place double-armed 2-0 polypropylene monofilament sutures on an MH needle, first through the strip, and then through both sides of the injury. A second strip is then held in a similar fashion so that the trauma surgeon then places both needles thru the second Teflon strip. The sutures are then gently tied against the Teflon strip and/or pledget, which will buttress and reinforce the suture line. This maneuver must be repeated until total control of ventricular hemorrhage is achieved. The authors have recently used commercially made fibrin sealants to seal complex ventricular injuries.70,74

Coronary Artery Injuries

The repair of ventricular injuries adjacent to coronary arteries can be very challenging. Injudicious and/or inappropriate placement of sutures during cardiorrhaphy may narrow and/or occlude a coronary artery or one of its branches. Therefore, it is recommended that sutures be placed underneath the bed of the coronary artery. Coronary arteries are usually divided into three segments: proximal, middle, and distal. Injuries to the proximal segment of a coronary artery will usually require cardiopulmonary bypass for repair, although this is infrequently necessary. Injuries of the middle segment of the coronary artery may also require cardiopulmonary bypass, or if ligated in desperation, may result in immediate myocardial infarction at the operating table. These patients may benefit from the institution of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation followed by aortocoronary bypass. Lacerations of the distal segment of the coronary artery particularly in the distal-most third of the vessel are managed by ligation.70,74

Use of Bioprosthetic and Autogenous Materials

Trauma surgeons are familiar with the use of Teflon pledgets and/or strips to buttress suture lines on friable myocardial tissue. Mattox18 provided the first reference in the literature alluding to the use of this material. The authors strongly believe in the necessity to buttress complex suture lines and use Teflon when indicated. However, no studies have been performed to determine if the use of Teflon increases tensile strength of the repair. The use of autogenous materials such as the pericardium to bolster suture lines is also well known. A small flap is developed and excised from the pericardium to be used in a manner similar to use of Teflon pledgets. Inexperienced trauma surgeons will often suture the pericardium to a ventricular injury causing the chamber to be fixated, which leads to dysrhythmias. This is mentioned, as it is a pitfall that should be avoided at all costs.70,74

Complex and Combined Injuries

As trauma surgeons and trauma centers continue to develop greater expertise in the management of penetrating cardiac injuries, and patients are subjected to greater degrees of violence in urban arenas of warfare, a significant number of patients arrive harboring multiple associated injuries in addition to their penetrating cardiac injuries. Complex and combined cardiac injuries can be defined as a penetrating cardiac injury plus associated neck, thoracic, thoracic-vascular, abdominal, abdominal vascular, or peripheral vascular injuries. These injuries are quite challenging to manage. Priority should be given early to the injury causing the greatest blood loss or threatening the patient’s life.70,74

RESULTS

The literature abounds with retrospective series describing the use of EDT. Great difficulties, however, exist in evaluating the results of these series. Close scrutiny reveals several flaws; most series have been retrospective reviews, many from institutions that employ this technique infrequently. Furthermore, many institutions report many overlapping studies that encompass the experience of many years. Whereas many series have selected physiologic parameters as predictors of outcome, none have statistically validated their predictive values. Invariably, these series omit data pertaining to the physiologic status of the patient upon initial presentation. To our knowledge, there is only one prospective study in the literature.67 As a result, there are still many questions to be answered.25

Well-known physiologic factors predictive of poor outcome include prehospital and ED absence of vital signs, fixed and dilated pupils, absence of cardiac rhythm and motion in the extremities, and agonal breathing. Similarly, the absence of a palpable pulse in the presence of cardiopulmonary arrest is also predictive of poor outcome. These factors have been validated by Asensio and colleagues,12,13 who tracked cases in the field, during transport, and upon arrival in the ED in two prospective studies dealing with penetrating cardiac injuries. Interestingly enough, many of these physiologic predictors of outcome, as well as any data describing the physiologic condition of the patient prior to EDT, are often absent in many studies.1,2,25

Previous work by Buckman et al.17 and Asensio and colleagues12,13 applied and validated the cardiovascular respiratory score (CVRS) of the trauma score (TS). The cardiovascular respiratory component of the trauma score reflects individual elements of blood pressure, respiratory rate, respiratory effort and capillary refill. The highest possible CVRS is 11, which denotes a systolic blood pressure of greater than 90 mm Hg, respiratory rates that fluctuate between 10 and 24/min along with a normal respiratory effort and capillary refill. The lowest possible CVRS score is zero, and reflects an absence of blood pressure, no palpable carotid pulse along with an absence of breathing, respiratory effort, and capillary refill. This score has been statistically validated and applied to the only three perspective cardiac injury series reported in the literature.

Asensio and colleagues,2 in the only prospective study on the use of EDT reported in the literature, analyzed parameters measuring the physiologic condition of patients incurring cardiopulmonary arrest in the field, during transport, and upon arrival at the trauma center. The CVRS, injury mechanism, and anatomic site of injury along with restoration of blood pressure were tracked prospectively with the objectives of identifying a set of parameters that would reliably predict mortality and exclude patients from EDT. This 2-year prospective study had a single inclusion criterion—cardiopulmonary arrest secondary to traumatic injury—as well as a single intervention, EDT for resuscitation. The main outcome of this study was survival at 1 hour and survival to discharge.

A total of 162 patients (75%) succumbed in the ED. Fifty-three patients (25%) survived up to 1 hour, after successful ED resuscitation with some restoration of vital signs so that they could be transported immediately to the OR. Of the 215 patients, only 6 (3%) survived, all of whom sustained cardiac injuries. None of the 48 patients who were injured due to blunt trauma survived. Upon comparing patients succumbing in the ED with those who survived at least 1 hour, all physiologic parameters were predictive of outcome (p<0.001). When all patients who survived 1 hour were compared with overall survivors, none of the physiologic parameters predicted outcome. Duration of CPR (p=0.04), penetrating mechanism of injury (p<0.001), and exsanguination (p<0.006) were predictors of outcome. The CVRS showed a trend toward the prediction of survival (p=0.07). When all nonsurvivors were compared with survivors, restoration of blood pressure was a strong predictor of outcome (p<0.001).

The authors concluded from these data that physiologic parameters plus the CVRS score were predictive of survival for patients undergoing EDT. On the basis of these criteria, the authors estimated that 75% of these patients could be safely excluded from this procedure at a cost savings of over $500,000 at their institution, and recommended that EDT should be limited to patients sustaining penetrating cardiac injuries and should not be applied to patients sustaining cardiopulmonary arrest secondary to blunt trauma.

Precisely because of the lack of uniformity in the reporting process in many of the reports in the literature, Asensio and colleagues25 in the working group of the Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Outcomes of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma closely scrutinized the literature to generate practice management guidelines for EDT.

In an extensive literature search, studies were classified into three classes. Class I comprises prospective randomized controlled trials and remains the gold standard of all clinical trials. In this category, the studies found were generally poorly designed, had inadequate numbers, or suffered from methodological inadequacies, rendering them clinically nonsignificant. In this group, no prospective randomized controlled trials were found. Studies in class II included clinical studies in which data were collected prospectively, as well as retrospective analyses based on clearly reliable data. Included here are observational, cohort, prevalence, and case-controlled studies. The authors found 29 studies that qualified for class II, three of which were prospective. Finally, for class III—defined as retrospectively collected data including clinical series, databases or registries, case reviews, case reports, and expert opinion—the authors located 63 studies.25

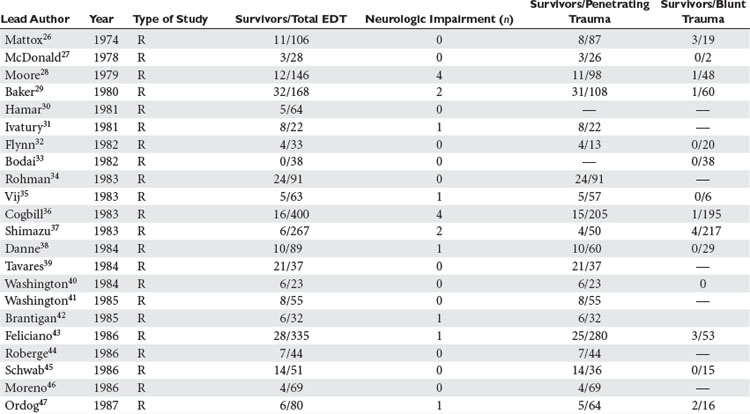

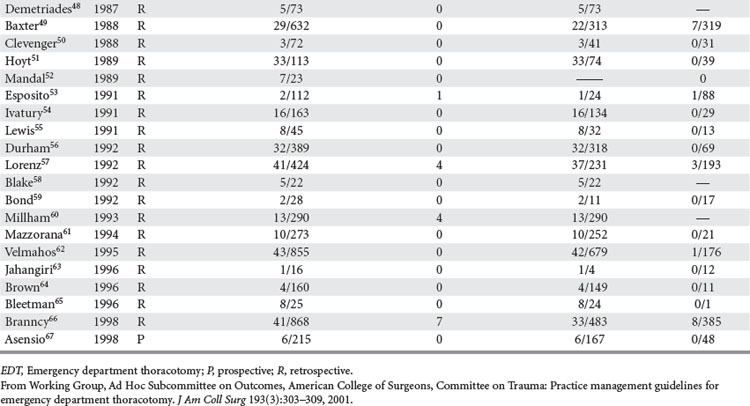

Analysis was conducted by stratifying the series into series dealing with EDT, series reporting neurologic outcomes of patients subjected to EDT, series dealing exclusively with penetrating cardiac injuries, and series dealing with pediatric patients. In the 42 series25–67 dealing with EDT (Table 2), there were 7035 EDTs and 551 survivors, for a survival rate of 7.83%. When data were stratified according to mechanism of injury, there were 4482 thoracotomies for penetrating injuries; of these, 500 patients survived, yielding a survival rate of 11.16%. There were 2193 thoracotomies performed for blunt injuries; only 35 patients survived, for a survival rate of 1.60%.25–67

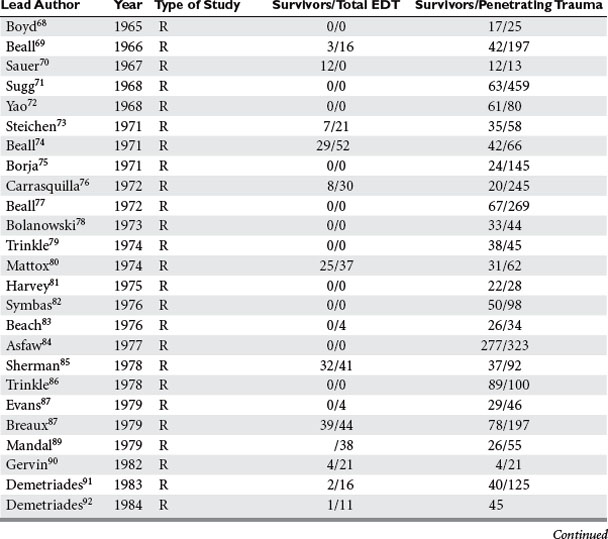

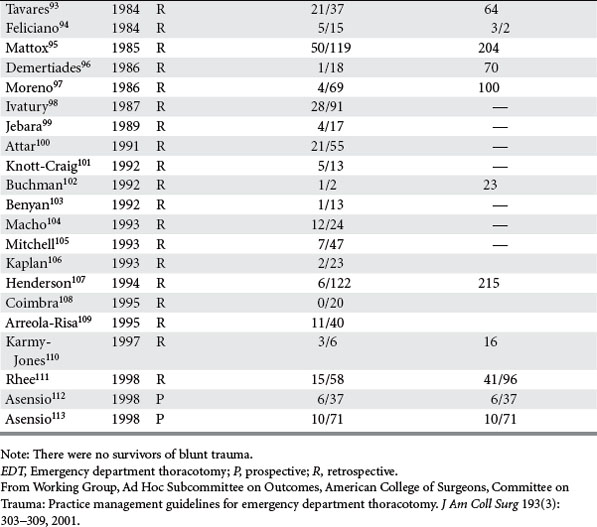

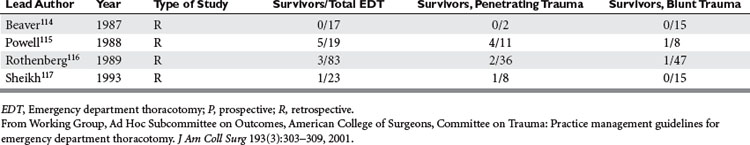

Of the 14 series reporting neurologic outcomes and their results,27,28,30,34–37,41,42,46,52,56,59,65 a total of 4520 patients were subjected to EDT with 226 survivors, yielding a 5% survival rate. Of these 226 survivors, 34 (15%) survived with neurologic impairment. In the series dealing exclusively with EDTs performed to repair penetrating cardiac injuries (Table 3), in a total of 1165 EDTs, 363 patients survived, yielding a survival rate of 31.1%. Only four series were found that dealt exclusively with pediatric patients (Table 4). There were 142 EDTs performed. Of 57 thoracotomies performed for penetrating injuries, 7 patients survived, yielding a survival rate of 12.2%. Eighty-five thoracotomies were performed for blunt injuries; 2 patients survived, for a survival rate of 2.3%.

In conclusion, EDT remains a very powerful tool in the trauma surgeons’ armamentarium. It should be employed wisely with strict indications, and should only be performed by trauma surgeons and surgeons properly trained. Only by judicious scientific inquiry can we push the envelope, save lives, and advance science.1–4,25

1 Asensio JA, Tsai KJ. Emergency department thoracotomy. In: Demetriades D, Asensio JA, editors. Trauma Management. Georgetown, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2000:271-279.

2 JA Asensio, D Hanpeter & D Demetriades: The futility of liberal utilization of emergency department thoracotomy. A prospective study. Proceedings of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma 58th Annual Meeting, September 1998, Baltimore, p. 210

3 Asensio JA, Hanpeter D, Gomez H, et al. Exsanguination. In: Shoemaker W, Greenvik A, Ayres SM, et al, editors. Textbook of Critical Care. 4 ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:37-47.

4 Asensio JA, Hanpeter D, Gomez H, et al. Thoracic injuries. In: Shoemaker W, Greenvik A, Ayres SM, et al, editors. Textbook of Critical Care. 4 ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:337-348.

5 Biffl WL, Moore EE, Harken AH. Emergency department thoracotomy. In: Mattox KL, Feliciano DV, Moore EE, editors. Trauma. 4 ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000:245-259.

6 Rehn L, Ueber Penetrerende Herzwunden und Herznaht. Arch Klin Chir. 1897;55:315. Beck CS. Wounds of the heart: the technic of suture. Arch Surg. 1926;13:205-227. As quoted in

7 Duval P, Le incision median thoraco-laparotomy. Bull Mem Soc Chir Paris. 1907;33:15. Ballana C. Bradshaw lecture. The surgery of the heart. Lancet. 1920;CXCVIII:73-79. As quoted in

8 Spangaro S, Sulla tecnica da seguire negli interventi chirurgici per ferite del cuore e su di un nuovo processo di toracotomia. Clin Chir Milan. 1906;14:227. Beck CS. Wounds of the heart: the technic of suture. Arch Surg. 1926;13:205-227. As quoted in

9 Beall AC, Oschner JL, Morris GC, et al. Penetrating wounds of the heart. J Trauma. 1961;1:195-207.

10 Beall AC, Dietrich EB, Crawford HW. Surgical management of penetrating cardiac injuries. Am J Surg. 1966;112:686.

11 Waterworth PD, Musleh G, Greenhalgh D, Tsang A. Innovative use of Octopus IV stabilizer in cardiac truma. Ann Thoracic Surgery. 2005;80:1008-1010.

12 Asensio JA, Murray J, Demetriades D, et al. Penetrating cardiac injuries: a prospective study of variables predicting outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186(1):24-34.

13 Asensio JA, Berne JD, Demetriades D, et al. One hundred five penetrating cardiac injuries. A 2-year prospective evaluation. J Trauma. 1998;44(6):1073-1082.

14 Asensio JA, Forno W, Gambaro E, et al. Penetrating cardiac injuries: a complex challenge. Ann Chir Gynecol. 2000;89(2):155-166.

15 Asensio JA, Hanpeter D, Gomez H, et al. Thoracic injuries. In: Shoemaker W, Greenvik A, Ayres SM, et al, editors. Textbook of Critical Care. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:337-348.

16 Asensio JA, Stewart BM, Murray J, et al. Penetrating cardiac injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 1996;76(4):685-724.

17 Buckman RF, Badellino MM, Mauro LH, et al. Penetrating cardiac wounds: prospective study of factors influencing initial resuscitation. J Trauma. 1993;34(5):717-727.

18 Mattox KL, Espada R, Beall AC, et al. Performing thoracotomy in the emergency center. J Am Coll Emerg Phys. 1974;3:13-17.

19 Beall AC, Morris GC, Cooley DA. Temporary cardiopulmonary bypass in the management of penetrating wounds of the heart. Surgery. 1962;52:330-337.

20 Boyd TF, Strieder JW. Immediate surgery for traumatic heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1965;50:305-315.

21 Sugg WL, Rea WJ, Ecker RR, et al. Penetrating wounds of the heart: an analysis of 459 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1968;56:531-545.

22 Beall AC, Gasior RM, Bricker DL. Gunshot wounds of the heart: changing patterns of surgical management. Ann Thorac Surg. 1971;11:523-531.

23 Steichen FM, Dargan EL, Efron G. A graded approach to the management of penetrating wounds to the heart. Arch Surg. 1971;103:574-580.

24 Mattox KL, Beall AC, Jordan GL, et al. Cardiorraphy in the emergency center. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1974;68:886-895.

25 Asensio JA, Wall M, Minei J, et al. Working Group, Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Outcomes, American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma: Practice management guidelines for emergency department thoracotomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193(3):303-309.

26 Mattox KL, Espada R, Beall AC. Performing thoracotomy in the emergency center. J Am Coll Emerg Physician. 1974;3:13-17.

27 McDonald JR, McDowell RM. Emergency department thoracotomies in a community hospital. J Am Coll Emerg Physician. 1978;7:423-428.

28 Moore EE, Moore JB, Galloway AC, et al. Postinjury thoracotomy in the emergency department: a critical evaluation. Surgery. 1979;86:590-598.

29 Baker CC, Caronna JJ, Trunkey DD. Neurologic outcome after emergency room thoracotomy for trauma. Am J Surg. 1980;139:677-681.

30 Hamar TJ, Oreskovich MR, Copass MK, et al. Role of emergency thoracotomy in the resuscitation of moribund trauma victims. 100 consecutive cases. Am J Surg. 1981;142:96-99.

31 Ivatury RR, Shah PM, Ito K, et al. Emergency room thoracotomy for the resuscitation of patients with “fatal” penetrating injuries of the heart. Ann Thorac Surg. 1981;32:377-385.

32 Flynn TC, Ward RE, Miller PW. Emergency department thoracotomy. Ann Emerg Med. 1982;11:45-48.

33 Bodai BI, Smith JP, Blaisdell FW. The role of emergency thoracotomy in blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1982;22:487-491.

34 Rohman M, Ivatury RR, Steichen FM, et al. Emergency room thoracotomy for penetrating cardiac injuries. J Trauma. 1983;23:570-576.

35 Vij D, Simoni E, Smith RF, et al. Resuscitative thoracotomy for patients with traumatic injury. Surgery. 1983;94:554-561.

36 Cogbill TH, Moore EE, Millikan JS, et al. Rationale for selective application of emergency department thoracotomy in trauma. J Trauma. 1983;23:453-460.

37 Shimazu S, Shatney CH. Outcome of trauma patients with no vital signs on hospital admission. J Trauma. 1983;23:213-216.

38 Danne PO, Finelli F, Champion HR. Emergency bay thoracotomy. J Trauma. 1984;24:796-802.

39 Tavares S, Hankins JR, Moulton AL, et al. Management of penetrating cardiac injuries: the role of emergency thoracotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1984;38:183-187.

40 Washington B, Wilson RF, Steiger Z. Emergency thoracotomies for penetrating trauma. Curr Probl Surg. 1984:14-17.

41 Washington B, Wilson RF, Steiger Z, et al. Emergency thoracotomy: a four-year review. Ann Thorac Surg. 1985;40:188-191.

42 Brantigan MW, Tietz G. Emergency thoracotomy in an urban community hospital: initial cardiac rhythm as a new predictor of survival. Am J Emerg Med. 1985;3:311-315.

43 Feliciano DV, Bitondo CG, Cruse PA, et al. Liberal use of emergency center thoracotomy. Am J Surg. 1986;152:654-659.

44 Roberge RJ, Ivatury RR, Stahl W, et al. Emergency department thoracotomy for penetrating injuries: predictive value of patient classification. Am J Emerg Med. 1986;4:129-135.

45 Schwab WC, Adcock OT, Max MH. Emergency department thoracotomy (EDT): a 26-month experience using an “agonal” protocol. Am Surg. 1986;52:20-29.

46 Moreno C, Moore EE, Majure JA, et al. Pericardial tamponade: a critical determinant for survival following penetrating cardiac wounds. Trauma. 1986;26:821-825.

47 Ordog GJ. Emergency department thoracotomy for traumatic cardiac arrest. J Emerg Med. 1987;5:217-223.

48 Demetriades D, Rabinowitz B, Sofianos C. Emergency room thoracotomy for stab wounds to the chest and neck. J Trauma. 1987;27:483-485.

49 Baxter TB, Moore EE, Moore JB, et al. Emergency department thoracotomy following injury: critical determinants for patient salvage. World J Surg. 1988;12:671-675.

50 Clevenger FW, Yarbrough DR, Reines HD. Resuscitative thoracotomy: the effect of field time on outcome. J Trauma. 1988;28:441-445.

51 Hoyt DB, Shackford SR, Davis JW, et al. Thoracotomy during trauma resuscitations-an appraisal by board-certified general surgeons. J Trauma. 1989;29:1318-1321.

52 Mandal AK, Oparah SS. Unusually low mortality of penetrating wounds of the chest-twelve years’ experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989;97:119-125.

53 Esposito TJ, Jurkovich GJ, Rice CL, et al. Reappraisal of emergency room thoracotomy in a changing environment. J Trauma. 1991;31:881-887.

54 Ivatury RR, Kazigo J, Rohman M, et al. “Directed” emergency room thoracotomy: a prognostic prerequisite for survival. J Trauma. 1991;31:1076-1082.

55 Lewis G, Knottenbelt JD. Should emergency room thoracotomy be reserved for cases of cardiac tamponade? Br J Accid Surg. 1991;22:5-6.

56 Durham LA, Richardson RJ, Wall MJJr, et al. Emergency center thoracotomy: impact of prehospital resuscitation. J Trauma. 1992;32:775-779.

57 Lorenz PH, Steinmetz B, Lieberman J, et al. Emergency thoracotomy: survival correlates with physiologic status. J Trauma. 1992;32:780-783.

58 Blake DP, Gisbert VL, Ney AL, et al. Survival after emergency 5 department versus operating room thoracotomy for penetrating cardiac injuries. Am Surg. 1992;58:329-333.

59 Bond M, Vanek VW, Bourguet CC. Emergency room resuscitative thoracotomy: When is it indicated? J Trauma. 1992;33:714-721.

60 Millham FH, Grindlinger GA. Survival determinants in patients undergoing emergency room thoracotomy for penetrating chest injury. J Trauma. 1993;34:332-336.

61 Mazzorana V, Smith RS, Morabito DJ, et al. Limited utility of emergency department thoracotomy. Am Surg. 1994;60:516-521.

62 Velmahos GC, Degiannis E, Souter I, et al. Outcome of a strict policy on emergency department thoracotomies. Arch Surg. 1995;130:774-777.

63 Jahangiri M, Hyde J, Griffin S, et al. Emergency thoracotomy for thoracic trauma in the accident and emergency department: indications and outcome. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1996;78:121-124.

64 Brown SE, Gomez GA, Jacobson LE, et al. Penetrating chest trauma: should indications for emergency room thoracotomy be limited? Am Surg. 1996;62:530-534.

65 Bleetman A, Kasem H, Crawford R. Review of emergency thoracotomy for chest injuries in patients attending a UK accident and emergency department. Injury. 1996;27:119-122.

66 Branncy SW, Moore EE, Feldhaus KM, et al. Critical analysis of two decades of experience with post injury emergency department thoracotomy in a regional trauma center. J Trauma. 1998;4:87-94.

67 JA Asensio, D Hanpeter & D Demetriades, et al: The futility of the liberal utilization of emergency department thoracotomy. A prospective study. Proceedings of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma 58th Annual Meeting, September 1998, Baltimore, Maryland, p. 210

68 Boyd TF, Strieder JW. Immediate surgery for traumatic heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1965;50:305-315.

69 Beall AC, Dietrich EB, Crawford HW, et al. Surgical management of penetrating cardiac injuries. Am J Surg. 1966;112:686-691.

70 Sauer PE, Murdock CE. Immediate surgery for cardiac and great vessel wounds. Arch Surg. 1967;95:7-11.

71 Sugg WL, Rea WJ, Ecker RR, et al. Penetrating wounds of the heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1968;56:530-545.

72 Yao ST, Vanecko RM, Printen K, Shoemaker WC. Penetrating wounds of the heart: a review of 80 cases. Ann Surg. 1968;168:67-78.

73 Steichen FM, Dargan EL, Efron G, et al. A graded approach to the management of penetrating wounds of the heart. Arch Surg. 1971;103:574-580.

74 Beall AC, Gasior RM, Briker DL. Gunshot wounds of the heart. Ann Thorac Surg. 1971;11:523-531.

75 Borja AR, Ransdell HT. Treatment of penetrating gunshot wounds of the chest. Am J Surg. 1971;122:81-84.

76 Carrasquilla C, Wilson RF, Walt AJ, et al. Gunshot wounds of the heart. Ann Thorac Surg. 1972;13:208-213.

77 Beall AC, Patrick TD, Ikles JE, et al. Penetrating wounds of the heart: changing patterns of surgical management. J Trauma. 1972;12:468-473.

78 Bolanowski PS, Swaminathan AP, Neville WE. Aggressive surgical management of penetrating cardiac injuries. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1973;66:52-57.

79 Trinkle JK, Marcos J, Grover FL, et al. Management of the wounded heart. Ann Thorac Surg. 1974;17:231-236.

80 Mattox KL, Beall AC, Jordan GL, et al. Cardiorrhaphy in the emergency center. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1974;68:886-895.

81 Harvey JC, Pacifico AD. Primary operative management method of choice for stab wounds to the heart. South Med J. 1975;68:149-152.

82 Symbas PN, Harlaftis N, Waldo WJ. Penetrating cardiac wounds: a comparison of different therapeutic methods. Ann Surg. 1976;183:377-381.

83 Beach PM, Bognolo D, Hutchinson JE. Penetrating cardiac trauma. Experience with thirty-four patients in a hospital without cardiopulmonary bypass capability. Am J Surg. 1976;131:411-415.

84 Asfaw I, Arbulu A. Penetrating wounds of the pericardium and heart. Surg Clin North Am. 1977;57:37-49.

85 Sherman M, Saini UK, Yardoz MD, et al. Management of penetrating heart wounds. Am J Surg. 1978;135:553-558.

86 Trinkle JK, Toon RS, Franz JL, et al. Affairs of the wounded heart: penetrating cardiac wounds. J Trauma. 1978;19:467-472.

87 Evans J, Gray LA, Payner A, et al. Principles for the management of penetrating cardiac wounds. Ann Surg. 1979;189:777-784.

88 Breaux EP, Dupont JB, Albert HM, et al. Cardiac tamponade following penetrating mediastinal injuries: improved survival with early pericardiocentesis. J Trauma. 1979;19:461-466.

89 Mandal AK, Awariefe SO, Oparah SS. Experience in the management of 50 consecutive penetrating wounds of the heart. Br J Surg. 1979;66:565-568.

90 Gervin AS, Fischer RP. The importance of prompt transport in salvage of patients with penetrating heart wounds. J Trauma. 1982;22:443-448.

91 Demetriades D, Vander Veen BW. Penetrating injuries of the heart: experience over two years in South Africa. J Trauma. 1983;23:1034-1041.

92 Demetriades D. Cardiac penetrating injuries: personal experience of 45 cases. Br J Surg. 1984;71:95-97.

93 Tavares S, Hankins JR, Moulton AL, et al. Management of penetrating cardiac injuries: The role of emergency thoracotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1984;38:183-187.

94 Feliciano DV, Bitondo CG, Mattox KL, et al. Civilian trauma in the 1980’s. A 1-year experience with 456 vascular and cardiac injuries. Ann Surg. 1984;199:717-724.

95 Mattox KL, Limacher MG, Feliciano DV, et al. Cardiac evaluation following heart injury. J Trauma. 1985;25:758-765.

96 Demetriades D. Cardiac wounds. Experience with 70 patients. Ann Surg. 1986;203:315-317.

97 Moreno C, Moore EE, Majure JA, et al. Pericardial tamponade: a critical determinant for survival following penetrating cardiac wounds. J Trauma. 1986;26:821-825.

98 Ivatury RR, Rohman M, Steichen FM, et al. Penetrating cardiac injuries: Twenty-year experience. Am Surg. 1987;53:310-317.

99 Jebara VA, Saade B. Penetrating wounds to the heart: a wartime experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;47:250-253.

100 Attar S, Suter CM, Hankins JR, et al. Penetrating cardiac injuries. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:711-716.

101 Knott-Craig CJ, Dalron RP, Rossouw GJ, et al. Penetrating cardiac trauma: management strategy based on 129 surgical emergencies over 2 years. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53:1006-1009.

102 Buchman TG, Phillips J, Menker JB. Recognition, resuscitation and management of patients with penetrating cardiac injuries. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;174:205-210.

103 Benyan AKZ, Al-A’Ragy HH. The pattern of penetrating cardiac trauma in Basrah province: personal experience with seventy-two cases in a hospital without cardiopulmonary by-pass facility. Int Surg. 1992;7:111-113.

104 Macho JR, Markinson RE, Schecter WP. Cardiac stapling in the management of penetrating injuries of the heart: rapid control of hemorrhage and decreased risk of personal contamination. J Trauma. 1993;34:711-716.

105 Mirchell ME, Muakkassa FF, Pool GV, et al. Surgical approach of choice for penetrating cardiac wounds. J Trauma. 1993;34:17-20.

106 Kaplan AJ, Norcross ED, Crawford FA. Predictors of mortality in penetrating cardiac injuries. Am Surg. 1993;9:338-342.

107 Henderson VJ, Smith SR, Fry WR, et al. Cardiac injuries: analysis of an unselected series of 251 cases. J Trauma. 1994;36:341-348.

108 Coimbra R, Pinto MCC, Razuk A, et al. Penetrating cardiac wounds: predictive value of trauma indices and the necessity of terminology standardization. Am Surg. 1995;61:448-452.

109 Arreola-Risa C, Rhee P, Boyle EM, et al. Factors influencing outcome in stab wounds of the heart. Am J Surg. 1995;169:553-556.

110 Karmy-Jones R, Van Wijngaarden MH, Talwar MK, et al. Penetrating cardiac injuries. Injury. 1997;28:57-61.

111 Rhee PM, Foy H, Kaufman C, et al. Penetrating cardiac injuries: a population-based study. J Trauma. 1998;45:366-370.

112 Asensio JA, Murray J, Demetriades D, et al. Penetrating cardiac injuries: prospective one-year preliminary report: an analysis of variables predicting outcome. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:24-33.

113 Asensio JA, Berne JD, Demetriades D, et al. One hundred and five penetrating cardiac injuries. A two-year prospective evaluation. J Trauma. 1998;44:1073-1083.

114 Beaver B, Colombani P, Buck J. Efficacy of emergency room thoracotomy in pediatric trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:19-23.

115 Powell R, Gill E, Jurkovich G. Resuscitative thoracotomy in children and adolescents. Am Surg. 1988;54:188.

116 Rothenberg S, Moore E, Moore FA, et al. Emergency department thoracotomy in children: a critical analysis. J Trauma. 1989;29:1322-1325.

117 Sheikh A, Culbertson C. Emergency department thoracotomy in children: rationale for selective application. J Trauma. 1993;34:323.