129 Emergency Contraception

• Emergency contraception (EC) is more effective the sooner it is administered, and its effectiveness decreases with time. It can be administered up to 120 hours after intercourse with reasonable effectiveness.

• EC is not effective in pregnancy, but it is also not harmful.

• Progestin-only EC (levonorgestrel, “Plan B”) is more effective than combined estrogen-progestin EC and has fewer side effects.

• In the United States, levonorgestrel EC (“Plan B”) is available to women older than 17 years without a prescription.

• Both levonorgestrel doses (1.5 mg total) can be administered as a single, one-time dose.

• Hormonal EC can cause nausea. Antiemetics can help if administered 30 to 60 minutes before taking contraceptive pills.

• Because patients can still become pregnant for the remainder of the cycle after the use of EC, alternative methods of contraception must still be used, and patients should immediately resume taking their regular oral contraceptive pills.

• A pelvic examination is not a prerequisite to providing EC.

• Many pharmacies do not have Plan B available in timely fashion; therefore, it is prudent to give the pills directly to the patient.

Epidemiology

Approximately 50% of women between the ages of 15 and 44 years have had at least one unwanted pregnancy, which amounts to more than 3 million unwanted pregnancies annually in the United States.1 No contraceptive method is 100% effective, and the failure rates of contraceptives are surprisingly high (Table 129.1).2 Because contraceptive failure is so common, most emergency physicians (EPs) will deal with this issue on a regular basis, and they should be aware of the indications and complications of this treatment.

Table 129.1 Failure Rates of Selected Contraceptive Methods Within 1 Year (%)

| METHOD | PERFECT USE | TYPICAL USE |

|---|---|---|

| Chance | 85 | 85 |

| Combination pill | 0.1 | 5.0 |

| Progestin-only pill | 0.5 | 5.0 |

| Male condom | 3.0 | 14.0 |

| Diaphragm | 6.0 | 20 |

| Spermicide | 6.0 | 26 |

| Periodic abstinence—calendar method | 9.0 | NA |

| Hormonal emergency contraception | 0.1 | 3.0 |

| Copper IUD | 0.1 | NA |

IUD, Intrauterine device; NA, not available.

From Kafrissen M, Adashi E. Fertility control: current approaches and global aspects. In: Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, et al, editors. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003. pp. 665–708.

Pathophysiology

The primary mechanism of action of estrogen-progestin EC is inhibition of ovulation. Additional possible contributing mechanisms include thickening of cervical mucus, altered sperm transport, and changes in the endometrial lining.3 Progestin-only methods (levonorgestrel) do not appear to have an effect on the endometrium. Ulipristal is a progesterone receptor modulator, similar to mifepristone. The primary mechanism of these drugs at the EC dose is inhibition of ovulation, although the possibility of an additional affect on uterine implantation cannot be entirely excluded. Once an embryo is implanted in the endometrium, hormonal EC has no effect on a pregnancy and does not cause abortion.4

It is important for the EP to understand the mechanism of action of EC to accurately address the concerns of individual patients. According to the definition of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, pregnancy is established at the time of implantation of the embryo in the uterus.5 By this definition, hormonal EC drugs are not abortifacients because these medications do not interfere with already established (implanted) pregnancies. However, individual patients may have a different understanding of terms such as conception and abortion than the medical community does. The known facts should be presented to patients simply and clearly so that they will be informed participants in their health care (Table 129.2 and Boxes 129.1 and 129.2).6,7

| MYTH | FACT |

|---|---|

| EC causes a “medical abortion.” | EC has no effect on an established pregnancy, and EC agents are not teratogenic. |

| The primary mechanism of action of EC is inhibition of ovulation. | |

| Estrogen-progestin combination EC may inhibit implantation of a fertilized egg. | |

| If EC is too easily available, women will “abuse” it and use EC instead of regular forms of birth control. | Women who receive advance prescriptions for EC agents are not less likely to use regular forms of birth control. |

| EC agents contain high doses of hormones and are dangerous to use. | The small dose of hormones in EC agents is extremely safe and can be used by virtually any woman. |

| EC is readily available in the United States. | Although FDA approval for over-the-counter EC medications is an improvement, availability in EDs, as well as pharmacies, is variable. The emergency physician must be a patient advocate and ensure that the patient is able to obtain the medication that has been prescribed. |

EC, emergency contraception; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Box 129.1

Sample Indications for Using Emergency Contraception

Failure to use a contraceptive method

Dislodged, broken, or improperly used condom, diaphragm, or cervical cap

Unprotected intercourse within 7 days of starting oral contraceptives

Two or more missed estrogen-progestin birth control pills

One or more missed progestin-only birth control pills

Removal of a contraceptive skin patch or ring

Unprotected intercourse within 14 days of first depot medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera) injection

Ejaculation on the external genitalia without reliable contraception

Sexual assault when the woman is not using reliable contraception

Data from Conard LA, Gold MA. Emergency contraception. Adolesc Med Clin 2005;16:585–602; and WHO Fact Sheet. Levonorgestrel for emergency contraception. October 2005. Available at http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/family_planning/docs/ec_factsheet.pdf.

Box 129.2 Contraindications to and Complications of Emergency Contraception (EC)

There are no absolute contraindications to hormonal EC.

EC agents are not abortifacients, and EC is not effective in pregnancy. A urine pregnancy test should be performed before administering EC if the patient might be pregnant.

Relative contraindications to estrogen-containing EC include smokers older than 35 years and patients with a history of thrombophilia, stroke, heart attack, malignancy, deep vein thrombosis, and migraine with neurologic symptoms. In these cases, a progestin-only form of EC is recommended.

An intrauterine device should not be used by patients with multiple sexual partners or those at risk for sexually transmitted diseases.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Patients seen immediately after coitus should have no symptoms.

Patients requesting emergency contraception (EC) who are having medical symptoms (abdominal pain) should be evaluated for the cause of their symptoms.

If signs or symptoms consistent with pregnancy are present, a pregnancy test should be performed because EC is not effective in pregnant patients.

Patients requesting EC may be at risk for sexually transmitted diseases and should be counseled and either tested or referred for outpatient follow-up or testing.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

EC may be indicated in several circumstances, as listed in Box 129.1.

Treatment

Four regimens for EC are commonly used in the United States: combined estrogen-progesterone (“Yuzpe method”), progestin only (levonorgestrel), progesterone agonist-antagonist (ulipristal), and the copper intrauterine device (IUD). A combined regimen of estrogen and progesterone pills for EC was first reported and popularized in the 1970s by Yuzpe et al.8 and is often referred to as the Yuzpe method. The standard dosing in this regimen is two 100-mcg doses of ethinyl estradiol and 1 mg of norgestrel taken 12 hours apart. When taken within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse, this regimen will prevent approximately 75% of pregnancies.9 This method of EC has been effectively supplanted by progestin-only methods, which are more effective and have fewer side effects. The Yuzpe method is thus primarily a historical regimen.

A preferred, progestin-only method of EC has become popular and is marketed in the United States under the brand name Plan B, which consists of two 0.75-mg doses of levonorgestrel taken 12 hours apart. The recommended approach is to take the two doses simultaneously, which increases compliance, decreases side effects, and is equally effective. The EP should instruct the patient on this method because the packaging lists only the two-dose method (Table 129.3).

Table 129.3 Common Hormonal Methods of Emergency Contraception

| METHOD | CONTAINS | DOSING |

|---|---|---|

| Combination oral (Yuzpe method) | 0.1 mg ethinyl estradiol and 0.5 mg levonorgestrel | Two doses 12 hr apart |

| Progestin-only oral (Plan B) | 0.75 mg levonorgestrel | Two doses 12 hr apart |

| Progestin-only oral, single-dose regimen* | 1.5 mg levonorgestrel | One dose |

| Progesterone agonist-antagonist | 30 mg ulipristal acetate | one dose |

Ulipristal acetate (brand name Ella) is a progesterone agonist-antagonist that became available for use in the United States late in 2010. It is available by prescription only. Its effectiveness is similar to that of levonorgestrel, and ulipristal has been found to not be inferior to levonorgestrel in two well-conducted studies.10,11 It is administered as a single 30-mg dose taken within 120 hours of intercourse. The side effect profile of Ulipristal is remarkably similar to that of levonorgestrel, with about 20% of women experiencing headache and 10% to 15% experiencing nausea or dysmenorrhea (or both).11 Unlike levonorgestrel, which tends to bring about the next menses sooner than expected, thus relieving the patient of the fear of being pregnant, ulipristal is associated with a delay in subsequent menses by a mean of 2 days.

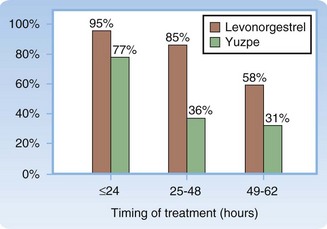

Of the hormonal EC methods, levonorgestrel and ulipristal are more effective and are recommended over the Yuzpe method. The difference in effectiveness varies with the timing of treatment (Fig. 129.1).9 Both levonorgestrel and ulipristal are less likely to cause nausea and vomiting than combined estrogen-progestin formulations are. Other hormonal methods have been used for EC but are less popular either because of questionable efficacy (danazol) or because of a higher incidence of side effects (high-dose estrogens).

The IUD is the most effective postcoital contraceptive and prevents more than 99% of pregnancies if inserted within 5 days of intercourse.12 This can be an ideal form of EC in patients who prefer to continue using an IUD as their contraceptive device for an extended period. IUDs should be avoided in patients with a history of sexually transmitted disease and in those with multiple sexual partners because IUD use increases the likelihood of pelvic inflammatory disease. This drawback makes an IUD unsuitable for patients seen after rape and for adolescent patients. Other contraindications to copper IUD insertion are cervical or endometrial cancer, unexplained vaginal bleeding, and copper allergy. Patients should be informed of its marked superiority in effectiveness over other methods of EC and be referred for IUD insertion if they choose this method.

Mifepristone (RU-486) is a progesterone antagonist that is effective in EC. It functions by inhibiting ovulation, as well as endometrial maturation. In the United States, a 600-mg dose of mifepristone is approved as an abortifacient for pregnancies up to 49 days. Lower doses of mifepristone, from 10 to 50 mg, are at least as effective as and probably more effective than levonorgestrel for EC and have a very good side effect profile.13 Mifepristone is administered as a single dose within 120 days of intercourse. The 10-mg dose is currently used routinely in several countries as EC. Mifepristone causes a 1-week delay in subsequent menses in about 20% of women who use it for EC, which understandably can cause patients anxiety. Currently, administration of mifepristone is limited to registered providers who contract with the patient to schedule three office visits. This restriction makes prescribing mifepristone in the ED impractical. Additionally, its use as an abortifacient has given the drug some notoriety that may make universal implementation a challenge in the future.14

Timing of Administration of Emergency Contraception

Hormonal EC is effective when administered up to 120 hours after intercourse. There is an inverse linear relationship between the time of administration of EC after unprotected intercourse and its effectiveness—the sooner that EC is started, the more effective it is.15 For this reason, it is of the utmost importance to begin EC as soon as possible. Many EDs stock levonorgestrel; if it is available through the hospital pharmacy, it can be given directly to the patient by the EP. If this is not possible, in addition to a prescription (if necessary) and instructions, the patient should be provided with a list of local 24-hour pharmacies that provide EC. It is advisable to call the pharmacies to confirm availability and expedite the preparation because as many as half of the pharmacies will not stock many forms of EC.16

Side Effects

The adverse effects of estrogen-progestin contraceptive drugs are primarily related to the estrogen component. The most common side effect is nausea, which affects half of women taking this regimen. Approximately 20% of women vomit as a result. Nausea and vomiting are significantly less common with progestin-only regimens (nausea in 18% and vomiting in 4%).17 The incidence and severity of nausea and vomiting can be decreased with the administration of an antiemetic 30 to 60 minutes before taking the EC agent. Meclizine (50 mg) has been used with success,18 but any antiemetic can be administered. If a patient vomits more than 1 hour after taking an EC drug, the dosage does not need to be repeated.19

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

1 Henshaw SK. Unintended pregnancies in the U.S. Fam Plann Perspec. 1998;30:24–29.

2 Kafrissen M, Adashi E. Fertility control: current approaches and global aspects. In: Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, et al. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003:665–708.

3 Conard LA, Gold MA. Emergency contraceptive pills: a review of the recent literature. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16:389–395.

4 Croxatto HB, Ortiz ME, Muller AL. Mechanisms of action of emergency contraception. Steroids. 2003;68:1095–1098.

5 Spinnato JA. Informed consent and the redefining of conception: a decision ill conceived? J Matern Fetal Med. 1998;7:264–268.

6 Conard LA, Gold MA. Emergency contraception. Adolesc Med Clin. 2005;16:585–602.

7 WHO Fact Sheet. Levonorgestrel for emergency contraception. October 2005. Available at http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/family_planning/docs/ec_factsheet.pdf

8 Yuzpe AA, Thurlow HJ, Ramzy I, et al. Post coital contraception—a pilot study. J Reprod Med. 1974;13:53–58.

9 WHO Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352:428–433.

10 Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer DF, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomised controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1089–1097.

11 Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555–562.

12 Cheng L, Gulmezoglu AM, Piaggio GP, et al. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2008. CD001324

13 WHO Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Comparison of three single doses of mifepristone as emergency contraception: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:697–702.

14 Langston A. Emergency contraception: update and review. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28:95–102.

15 Piaggio G, von Hertzen H, Grimes DA, et al. Timing of emergency contraception with levonorgestrel or the Yuzpe regimen. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Lancet. 1999;353:721.

16 Harrison T. Availability of emergency contraception: a survey of hospital emergency department staff. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:105–110.

17 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Emergency contraception. Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists, Number 69, December 2005.

18 Raymond EG, Creinin MD, Barnhart KT, et al. Meclizine for prevention of nausea associated with use of emergency contraceptive pills: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:271–277.

19 Hatcher RA. 10 common questions on emergency contraception. Contracept Technol Update. 1998;19(6):11–12.