45 Emergency Biliary Ultrasonography

• Hepatobiliary disease has a high prevalence and is a common cause of abdominal symptoms in patients seeking care in the emergency department.

• Biliary infections represent up to 25% of the causes of intraabdominal sepsis in the elderly.

• Poor sensitivity of the clinical and laboratory data for cholecystitis creates a large demand for hepatobiliary imaging.

• Ultrasound is the initial imaging modality of choice in evaluating the biliary tract for suspected infection or obstruction.

• Focused hepatobiliary ultrasound is a skill that can be effectively learned by emergency department physicians and performed rapidly at the patient’s bedside.

• Focused hepatobiliary ultrasound is a dynamic process that can be facilitated by proper patient positioning, inspiratory maneuvers, and Doppler evaluation.

• Beside ultrasound is a useful adjunct for the detection of ascites in patients with hepatic disease and can provide procedural guidance for paracentesis.

Introduction

Hepatobiliary disease is a common cause of abdominal pain in patients evaluated in the emergency department. Cholelithiasis is present in 20 to 25 million of Americans, which represents 10% to 15% of the adult population.1 Cholecystectomy has become the most common elective abdominal surgery performed in the United States.2 Significant clinical symptoms, however, do not develop in the majority of patients (up to 80%) with gallstones.3 Both the prevalence and the complication rate of cholelithiasis increase with age. Biliary infection is a common cause of abdominal sepsis in the elderly.

Review of Literature on Evaluation for Cholecystitis

Clinical findings and laboratory data lack acceptable sensitivity to rule out cholecystitis,4 which has led to the need for abdominal imaging to aid in determining the patient’s disposition. Commonly used imaging modalities to evaluate for cholecystitis and its complications are ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and cholescintigraphy or hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scanning. The sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound for the detection of cholelithiasis can approach 100% for providers with significant ultrasound experience.5 CT is much less sensitive than ultrasound for detecting cholelithiasis and misses up to 25% of gallstones.6 HIDA scanning has been reported to have high sensitivity for acute cholecystitis, but it does not provide an adequate structural evaluation of the hepatobiliary system. HIDA scanning also has limited availability in many locations and is not a practical screening modality in the emergency department setting. These distinctions make ultrasound the imaging modality of choice for the initial evaluation of patients with right upper quadrant pain and suspected cholecystitis.7

Emergency physicians have demonstrated the ability to effectively learn to perform point-of-care bedside hepatobiliary ultrasonography.8 Studies on emergency physician–performed biliary sonography have demonstrated sensitivities and specificities of up to 92% and 87% for the detection of cholelithiasis.9,10

Biliary Duct Evaluation

Transabdominal ultrasound is the initial imaging modality used to evaluate for suspected choledocholithiasis and obstruction of the biliary ducts. In the western world, gallstones are the most common cause of both biliary obstruction and cholangitis.11,12 Even with the most advanced equipment, the sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting choledocholithiasis is still essentially dependent on the examiner’s proficiency and can range between 22% and 100%.5,11,13–15 Specific data on the accuracy of emergency medicine physicians’ performance in detecting choledocholithiasis are not yet available and need further investigation. The overall specificity of transabdominal sonography for detection of common bile duct (CBD) stones is usually very high and ranges between 95% and 100%.11

Biliary Sepsis

In patients older than 65 years, cholecystitis and cholangitis each account for 12% of the causes of intraabdominal sepsis, or 24% of the total causes of intraabdominal sepsis combined.16 Bedside ultrasound can be used to detect this common entity and expedite the initiation of appropriate antibiotics and consultation if signs of biliary infection or obstruction are identified.

How to Scan, Probe Selection, and Machine Settings

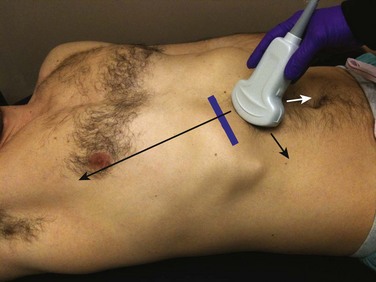

Bedside hepatobiliary imaging is most often performed with a lower-frequency (2- to 5-MHz) curvilinear probe (Fig. 45.1). The lower frequencies typically provide the most appropriate penetration relative to the depth of the structures of interest. In young or very thin patients with superficially located structures of interest, use of a higher-frequency probe may provide better image resolution. A phased-array probe can limit the amount of rib shadowing when intercostal imaging is required.

After selecting the abdominal preset, the gain should be adjusted accordingly. The depth needs to be optimized to see the structures of interest and the area posterior to them without creating needless dead space beyond them. Tissue harmonic imaging has been demonstrated to enhance the visibility of lesions and diagnostic confidence in abdominal imaging, particularly in areas containing echogenic tissue such as fat, calcium, or air.17 The tissue harmonics feature should be used when assessing the gallbladder because it typically reduces artifact interference and facilitates imaging. The sonographer should also be comfortable with the color and power Doppler functions, which can be used to distinguish the biliary ducts and gallbladder from adjacent vascular structures.

Systematic Scanning Approach

The authors suggest the following systematic approach:

1. The patient is placed in a supine position with the right arm raised above the head. To begin the examination, the sonographer should imagine a line that connects the patient’s umbilicus and right shoulder. The probe is placed immediately below the intersection of this line with the right inferior costal margin. The probe is placed parallel to the rib in about 45 degrees of angulation (see Fig. 45.1).

2. If the liver and aspects of the gallbladder are not in the visual field, the probe is fanned cephalad and caudal. If the gallbladder is still not visualized, the probe should be moved slowly along the inferior costal margin while repeating the fanning motion upward and downward and moving the probe laterally and medially.

3. If no liver tissue or gallbladder can be visualized along this inferior margin, the probe is moved one intercostal space up and placed in the same position where the line between the umbilicus and right shoulder intersects with now the last intercostal space. The probe is angled 60 to 90 degrees (Fig. 45.2). Next, the fanning maneuver is repeated and the probe moved within this intercostal space medially and laterally. The process is repeated in next intercostal space if needed.

4. If unsuccessful, the transducer is placed in a modified focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) view. Instead of angling down to the retroperitoneal location of the kidney, the transducer is angled up toward the tip of the liver, and the lateral margin of the liver is scanned until the gallbladder is located.

5. If unsuccessful after steps 1 to 4, the patient is placed in the left lateral decubitus position and steps 1 to 4 are repeated.

6. Finally, if feasible, have the patient stand up, which often drops the liver and gallbladder more caudally and makes them more accessible for sonography.

Gallbladder Evaluation

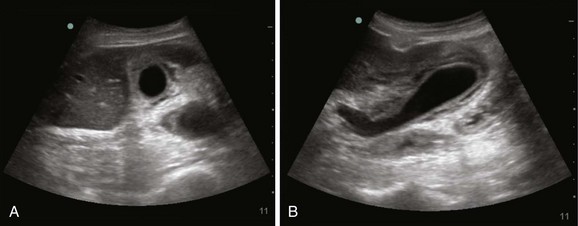

After locating the gallbladder, the probe is rotated clockwise and counterclockwise as needed to obtain a longitudinal (long-axis) view (Fig. 45.3). Next, the probe is moved medially and laterally to evaluate the entire gallbladder in long axis. A normal gallbladder has echogenic walls with an anechoic internal cavity. The gallbladder should be thoroughly evaluated for the presence or absence of cholelithiasis. Special attention should be paid to the gallbladder neck for impacted stones.

Following long-axis evaluation, the probe is rotated 90 degrees to the patient’s right (the indicator is rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise), which will give a transverse or short-axis view of the gallbladder (see Fig. 45.3). The probe should be angled or moved cephalad and caudad to evaluate the entire gallbladder. The gallbladder is scanned from the fundus to the neck. Again, particular attention should be directed to the gallbladder neck. Air artifact can obscure small stones in this area.

The next step should be to measure the thickness of the gallbladder wall (Fig. 45.4). Transmission of ultrasound waves through the fluid-filled gallbladder leads to enhancement of the posterior gallbladder wall, and posterior enhancement can result in overestimation of wall thickness. Hence, measurements are obtained at the anterior wall. Thickness of the anterior wall greater than 3 mm is considered abnormal.18 One should be aware that isolated increased gallbladder wall thickness is not a sensitive finding for detecting acute inflammation because it can be caused by multiple disease processes (e.g., chronic cholecystitis, ascites, hepatitis).19 Next, the area encompassing the gallbladder should be evaluated for the presence of pericholecystic fluid. This finding will appear as anechoic areas adjacent to the gallbladder. Pericholecystic fluid with septations, internal echoes, or thick walls may suggest perforation of the gallbladder with abscess formation.18

Finally, one should evaluate for a sonographic Murphy sign, which is defined as reproducible tenderness when transducer pressure is applied with the gallbladder in direct view. Correct evaluation for the Murphy sign includes repeating this maneuver on both the left and right sides next to the gallbladder, but with the gallbladder out of the visual field. With a true Murphy sign, tenderness or discomfort in areas away from the gallbladder should be significantly less.18

Common Bile Duct

Evaluation of the Common Bile Duct

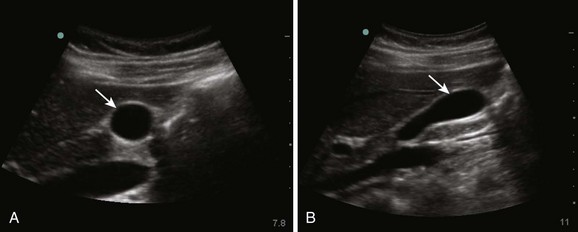

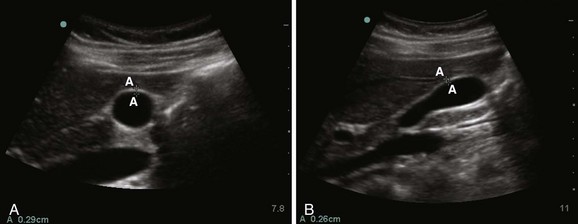

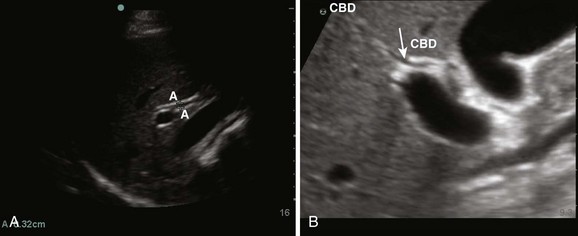

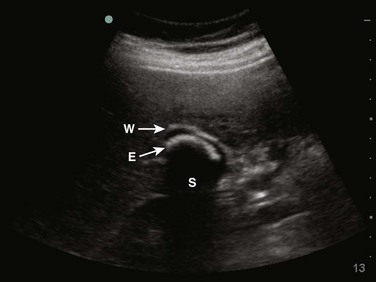

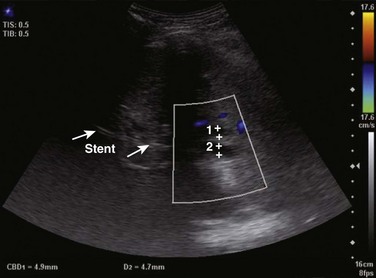

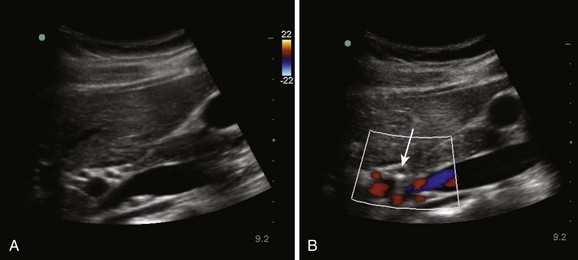

Once located, the sonographer should interrogate the portal triad with color Doppler to distinguish the CBD from the vessels. The hepatic artery and the portal vein should demonstrate flow, whereas the CBD will not (Fig. 45.5). In patients with sluggish portal flow, the sensitivity of the color or power Doppler settings should be adjusted until the vessels can be distinguished from the CBD. This should be carefully evaluated with a steady hand because motion artifact may produce the illusion of flow with more sensitive Doppler settings. Once the CBD is identified, it should be measured inner wall to inner wall in the transverse plane (Fig. 45.6).

Fig. 45.5 Common bile duct (CBD) in transverse view (A) showing no flow with Doppler (B, white arrow).

CBD diameter sizes of 1 mm per decade of life and CBD measurements of up to 1 cm following cholecystectomy have traditionally been accepted as normal.20 Measurements of CBD diameter accepted as normal range from 6 to 8 mm, with 7 mm commonly recognized as the upper limit of normal CBD size.21,22

More recent studies, however, do not correlate with the extent of traditionally expected increases in size in elderly and postcholecystectomy patients. A large study of patients older than 60 years found that mean bile duct size increases from 3.6 ± 0.26 mm at 60 years of age to 4 ± 0.25 mm in patients older than 85. Interestingly, 98% of ducts were less than 7 mm in diameter.23 Additionally, two large studies of patients undergoing cholecystectomy revealed postsurgical mean CBD diameters of 3.96 mm and 6.1 mm, respectively.24,25

Main Lobar Fissure

The gallbladder and the hepatic hilum are connected by the hepatic main lobar fissure (Fig. 45.7). Sonographically, it appears as a bright echogenic structure, relative to the adjacent liver, because of its fibrous content. It is a useful landmark that can be followed away from the gallbladder to locate the portal triad. Conversely, it can be traced from the portal triad to locate obscure gallbladders.

Images—Normal and Abnormal

Cholelithiasis

Gallstones tend to be rounded, mobile structures found in a dependent position. They have a highly reflective surface, which leads to visualization of a curved echogenic surface and shadowing posterior to the gallstone (Fig. 45.9). An attempt should be made to confirm that the gallstones identified are mobile and not impacted.

Acute Cholecystitis

Components of the focused sonographic examination for suspected cholecystitis are listed in Box 45.1. Because no single sonographic finding is diagnostic of cholecystitis, the ultrasound findings must be interpreted in conjunction with the clinical picture and laboratory data. The absence of cholelithiasis combined with a negative sonographic Murphy sign has a negative predictive value of 95%. When cholelithiasis is identified, its positive predictive value is increased in the presence of gallbladder wall thickening (95%) or a positive sonographic Murphy sign (92.2%).26 Pericholecystic fluid is also a common finding in patients with acute cholecystitis (Fig. 45.10).

Cholecystitis Variants

Emphysematous cholecystitis occurs when the gallbladder is infected with a gas-producing organism. Focal areas of gas and its characteristic appearance of small, hyperechoic areas with reverberation artifacts can be identified within the gallbladder wall (Fig. 45.11). This can be difficult to differentiate from overlying bowel in some cases. Less than 10% of cases of cholecystitis occur without cholelithiasis (acalculous cholecystitis).27 Debilitated or critically ill patients are most commonly affected (Fig. 45.12). Occasionally, a gallbladder abscess can develop (Fig. 45.13).

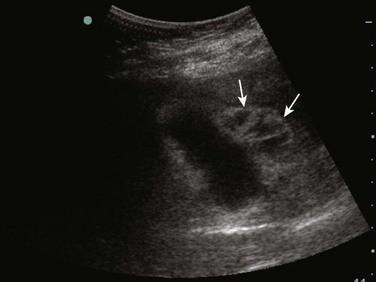

Wall-Echo-Shadow Sign

The wall-echo-shadow (WES) sign (Fig. 45.14) describes cholecystitis cases in which ultrasound reveals a thickened gallbladder wall closely followed by a hyperechoic line (representing the gallstone surface) and shadowing distal to it. In cases with minimal to no appreciable intervening bile, the WES sign can be difficult to differentiate from adjacent bowel, but the nature of the acoustic shadowing can help differentiate it. Gallstones have surfaces that are strongly reflective of ultrasound waves, thereby leading to a “clean” acoustic shadow, in contrast to the irregular shadowing produced by the scattering of ultrasound waves when bowel gas is encountered.

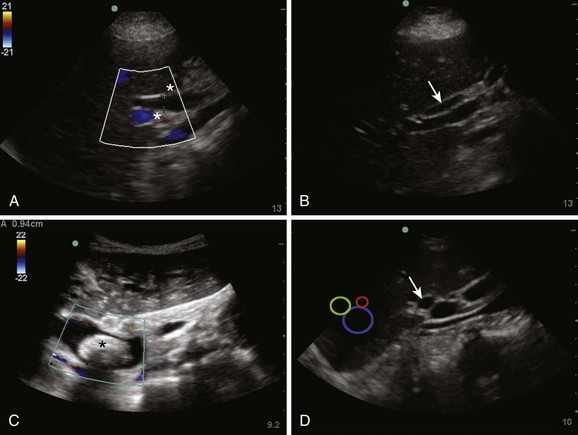

Intrahepatic Biliary Duct Dilation and Common Bile Duct Stones

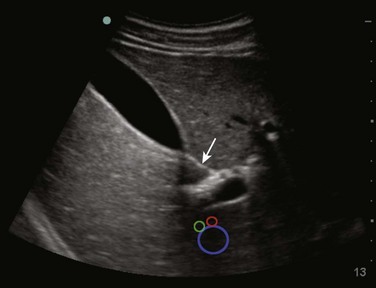

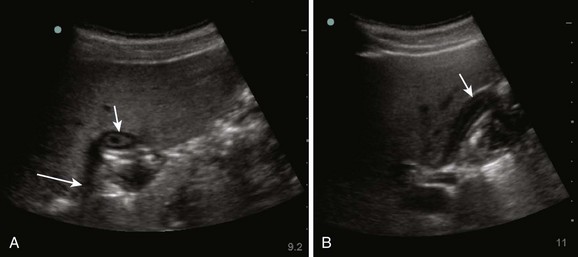

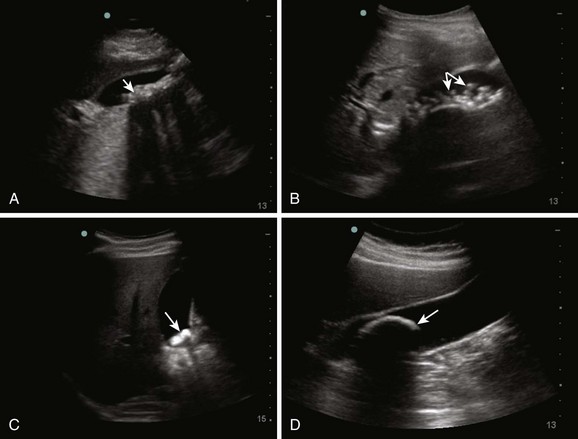

Dilation of the intrahepatic biliary ducts (Fig. 45.15) suggests ductal obstruction, although it is not diagnostic of a specific etiology. Obstruction has multiple causes, including choledocholithiasis (most common in the western world; Fig. 45.16), biliary duct stricture, ductal edema (as seen with Mirizzi syndrome), and compression from pancreatic masses.

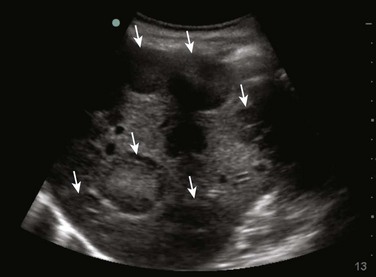

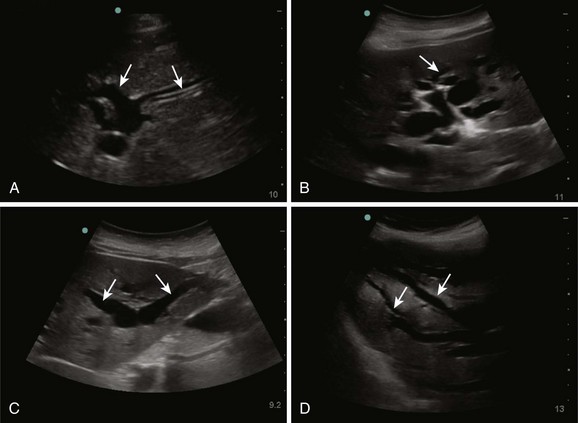

Fig. 45.15 Appearance of intrahepatic biliary duct dilation.

A-D, Multiple areas of intrahepatic ductal dilation (arrows) can be seen. Intrahepatic biliary ducts have echogenic walls and typically contain anechoic bile within. Color Doppler can be used to differentiate bile ducts (no flow) from vessels (see Fig. 45.16). Prominent dilation of major biliary ducts is sometimes described as a “staghorn” appearance (C).

When dilation of the CBD is found, the duct should be followed as far medially as possible to search for choledocholithiasis. Scanning through the liver may also reveal intrahepatic ductal dilation. Sensitivity is significantly dependent on operator performance and ranges from 25% to 100%.5

Liver Masses

Although use of ultrasound for evaluation of liver masses is beyond the scope of emergency medicine, observation of liver masses with bedside imaging is not uncommon. Common benign liver masses are hemangiomas (Fig. 45.17) and adenomas. Metastatic disease is the most frequent cause of malignant liver masses, and hepatocellular carcinoma is the most common primary malignant liver tumor. The sonographic features of hepatic masses depend on both the composition of the liver mass and secondary factors, such as associated edema, hemorrhage, and necrosis. The findings often mimic a target lesion (Fig. 45.18).

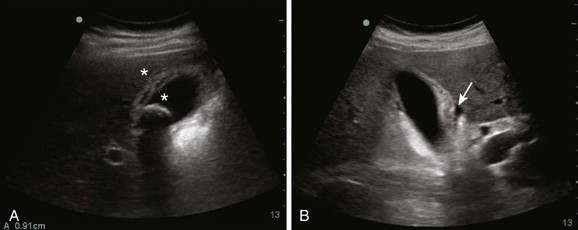

Identification of a liver mass should prompt appropriate referral for further work-up. Liver cysts can also be encountered, and the findings can be quite impressive in patients with polycystic liver disease, which is often combined with kidney disease (Fig. 45.19).

Hepatitis and Cirrhosis

Chronic liver disease and other conditions that elevate portal venous pressure can produce sonographic findings that can mimic acute cholecystitis. Gallbladder wall thickening and ascites are common findings. Ascites may be mistaken for pericholecystic fluid. As the disease progresses, the liver will eventually become hyperechoic in comparison with healthy liver tissue with tissue changes manifested as multiple liver nodules surrounded by echogenic fibrotic tissue. As the cirrhosis progresses, the liver typically decreases in size. Occasionally, a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt can be detected in patients with portal hypertension (Fig. 45.20).

Normal Variants

Polyps appear sonographically as fixed, pedunculated structures adherent to the gallbladder wall that are unchanged by patient positioning. Gallstones are typically mobile and settle to dependent areas of the gallbladder cavity unless they are impacted. Gallbladder polyps do not normally cause posterior shadowing (Fig. 45.21). Gallbladder folds are commonly encountered normal variants that appear as a bright echogenic line within the gallbladder lumen. A fold at the fundus is commonly seen and is termed a phrygian cap (Fig. 45.22). A fold may appear to divide the gallbladder into two sections. Careful imaging of the gallbladder in multiple planes can decrease the likelihood of misdiagnosis.

Fig. 45.22 Gallbladder fold.

The echogenic line partially transecting the middle of the gallbladder lumen is a gallbladder fold.

Adenomyomatosis is a common benign condition with a reported incidence of 2.8% to 5% that leads to hyperplastic changes and thickening of the gallbladder wall.28 It is usually asymptomatic, however. In the majority of cases it is associated with chronic biliary inflammation, most commonly gallstones in 25% to 75% but also cholesterolosis in 33% and pancreatitis. Cholesterol crystals precipitate in the bile trapped in Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses and cause a quite a distinct sonographic ring-down artifact (Fig. 45.23). Duplicated gallbladder, intrahepatic gallbladder, and congenital absence of the gallbladder are all uncommon variants that may be encountered.

Gallbladder Sludge and Gravel

Gravel is a variant of cholelithiasis that has a distinct ultrasound appearance identified as multiple small individual dependent stones (Fig. 45.24). Sludge produces a homogeneous, hyperechoic area in the gallbladder that does not produce shadowing. Sludge is viscous and settles to the dependent portion of the gallbladder, but it may take longer to settle than larger stones (Fig. 45.25).

How to Incorporate Evaluation of Suspected Cholecystitis into Practice

Evaluation of Jaundiced Patients and Those with Suspected Biliary Obstruction

Discovery of a dilated CBD should prompt the sonographer to follow the CBD as far medially as possible. The most common cause of biliary obstruction is choledocholithiasis, for which transabdominal ultrasound has a specificity of up to 95%.11 It should be noted, however, that ultrasound is not a specific modality for distinguishing the cause of biliary obstruction with the isolated finding of CBD dilation. Further imaging is often required.

1 Shaffer EA. Gallstone disease: epidemiology of gallbladder stone disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:981–996.

2 Stinton LM, Myers RP, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallstones. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:157–169. vii

3 Ransohoff DF, Gracie WA, Wolfenson LB, et al. Prophylactic cholecystectomy or expectant management for silent gallstones. A decision analysis to assess survival. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:199–204.

4 Trowbridge RL, Rutkowski NK, Shojania KG. Does this patient have acute cholecystitis? JAMA. 2003;289:80–86.

5 Nuernberg D, Ignee A, dietrich CF. [Ultrasound in gastroenterology. Biliopancreatic system]. Med Klin (Munich). 2007;102:112–126.

6 Bennett GL, Balthazar EJ. Ultrasound and CT evaluation of emergent gallbladder pathology. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:1203–1216.

7 Saini S. Imaging of the hepatobiliary tract. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1889–1894.

8 Gaspari RJ, Dickman E, Blehar D. Learning curve of bedside ultrasound of the gallbladder. J Emerg Med. 2009;37:51–56.

9 Scruggs W, Fox JC, Potts B, et al. Accuracy of ED bedside ultrasound for identification of gallstones: retrospective analysis of 575 studies. West. J Emerg Med. 2008;9:1–15.

10 Rosen CL, Brown DF, Chang Y, et al. Ultrasonography by emergency physicians in patients with suspected cholecystitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:32–36.

11 Attasaranya S, Fogel EL, Lehman GA. Choledocholithiasis, ascending cholangitis, and gallstone pancreatitis. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:925–960. x

12 Pedersen OM, Nordgård K, Kvinnsland S. Value of sonography in obstructive jaundice. Limitations of bile duct caliber as an index of obstruction. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;22:975–981.

13 Stott MA, Farrands PA, Guyer PB, et al. Ultrasound of the common bile duct in patients undergoing cholecystectomy. J Clin Ultrasound. 1991;19:73–76.

14 Pasanen P, Partanen K, Pikkarainen P, et al. Ultrasonography, CT, and ERCP in the diagnosis of choledochal stones. Acta Radiol. 1992;33:53–56.

15 Dong B, Chen M. Improved sonographic visualization of choledocholithiasis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1987;15:185–190.

16 Podnos YD, Jimenez JC, Wilson SE. Intra-abdominal sepsis in elderly persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:62–68.

17 Choudhry S, Gorman B, Charboneau JW, et al. Comparison of tissue harmonic imaging with conventional US in abdominal disease. Radiographics. 2000;20:1127–1135.

18 Rubens DJ. Hepatobiliary imaging and its pitfalls. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:257–278.

19 Carroll BA. Preferred imaging techniques for the diagnosis of cholecystitis and cholelithiasis. Ann Surg. 1989;210:1–12.

20 Holm AN, Gerke H. What should be done with a dilated bile duct? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12:150–156.

21 Coss A, Enns R. The investigation of unexplained biliary dilatation. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:155–159.

22 Bowie JD. What is the upper limit of normal for the common bile duct on ultrasound: how much do you want it to be? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:897–900.

23 Perret RS, Sloop GD, Borne JA. Common bile duct measurements in an elderly population. J Ultrasound Med. 2000;19:727–730.

24 Feng B, Song Q. Does the common bile duct dilate after cholecystectomy? Sonographic evaluation in 234 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:859–861.

25 Majeed AW, Johnson AG. The preoperatively normal bile duct does not dilate after cholecystectomy: results of a five year study. Gut. 1999;45:741–743.

26 Ralls PW, Colletti PM, Lapin SA, et al. Real-time sonography in suspected acute cholecystitis. Prospective evaluation of primary and secondary signs. Radiology. 1985;155:767–771.

27 Strasberg SM. Clinical practice. Acute calculous cholecystitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2804–2811.

28 Stunell H, Buckley O, Geoghegan T, et al. Imaging of adenomyomatosis of the gall bladder. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2008;52:109–117.