15 Emergencies in the First Weeks of Life

• Premature infants are at higher risk for most serious neonatal illnesses.

• Congenital heart and gastrointestinal anomalies are commonly manifested during the first month of life.

• A complete set of vital signs, including weight (undressed), is required for assessment and treatment of neonatal patients.

• The majority of neonates who have experienced an apparent life-threatening event have a normal appearance at the time of arrival at the emergency department.

• Laboratory work-up of infants after an apparent life-threatening event who have normal perinatal histories and normal findings on physical examination is most often unproductive.

• An echocardiogram may help distinguish between pulmonary and cardiac causes of cyanosis.

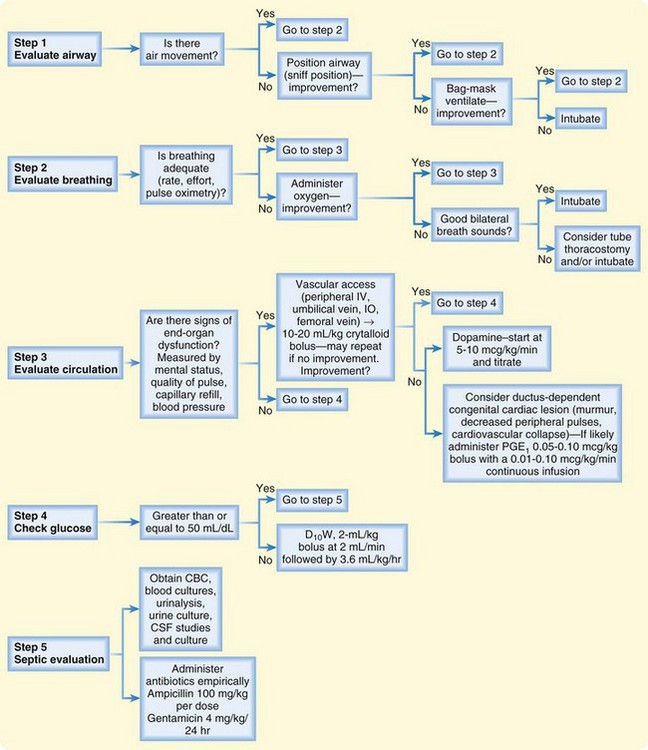

• Figure 15.1 summarizes the initial evaluation and management of seriously ill infants in the emergency department.

In 2007 the infant (child <1 year old) death rate was 686.9 per 100,000 population. This death rate is not approached again until the sixth decade of life. Two thirds of the deaths that occur in the first year of life do so in the first month.1

The Normal Neonate

Vital Signs

The core temperature in an infant is the same as that in an adult. Fever is generally recognized as a temperature higher than 38° C (100.4° F). Any temperature lower than 36.1° C (97° F) should raise concern for hypothermia. Because of limited thermoregulatory ability, neonates should be examined and treated in a warm ambient environment. See Table 15.1 for normal neonatal vital signs.

| Heart rate | 120-160 beats/min |

| Respiratory rate | 40-60 breaths/min |

| Blood pressure | Systolic pressure > 60 mm Hg |

| Temperature | 36.1-38° C (97-100.4° F) |

Apnea and Apparent Life-Threatening Events

Epidemiology

General estimates suggest that between 0.5% and 6.0% of infants will experience an apparent life-threatening event (ALTE). A prospective Austrian study conducted from 1993 to 2001 revealed an incidence of 2.46 per 1000 live births.2 In this study more than 60% of the events occurred in infants 2 months or younger.

Pathophysiology

ALTE is not a single disease entity but rather a constellation of signs and symptoms of numerous diseases that can have lethal consequences. The 1986 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on Infantile Apnea and Home Monitoring defined ALTE as “an episode that is frightening to the observer and is characterized by some combination of apnea (central or occasionally obstructive), change in color (usually cyanotic or pallid, but occasionally erythematous or plethoric), marked change in muscle tone (usually marked limpness), choking, or gagging.”3

The conventional definition of apnea is absence of breathing for 20 seconds or for a shorter period if associated with clinical signs such as cyanosis, hypotonia, and bradycardia. Because periods of apnea of up to 30 seconds have been observed in normal, healthy, asymptomatic term and preterm infants, the duration of apnea does not seem to be as clinically important as apnea associated with signs and symptoms.4 Apnea should be distinguished from the normal periodic breathing of newborns, which is characterized by irregular breathing and episodes of pauses. This latter pattern is more commonly seen in premature infants during sleep. Although similarities exist, ALTE is now considered a different pathophysiologic entity from sudden infant death syndrome.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The majority of neonates who have experienced an ALTE have a normal appearance at the time of arrival at the ED. Stratton et al. reported a prehospital study of 60 cases of ALTE in which 83% of the infants were asymptomatic by the time that emergency medical service personnel arrived.5 A comprehensive history and a thorough physical examination should be performed. One study showed that the history and physical examination were helpful in diagnosing the cause of ALTE in 70% of cases.6 The history should consist of a detailed description of the event, a prenatal and perinatal history, a review of systems, and a family history (especially child deaths, neurologic diseases, cardiac diseases, and congenital problems). Box 15.1 lists essential historical questions in these cases. A detailed physical examination should pay particular attention to the neurologic, respiratory, cardiac, and developmental components. Evidence of child abuse should be sought, including a funduscopic examination for retinal hemorrhage.

Box 15.1 Historical Questions to Ask the Caregiver of an Infant Who Has Had an Apparent Life-Threatening Event or Apnea

What was the appearance of the infant when found?

What was the infant doing when the episode occurred?

Were any interventions (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) necessary?

Was the infant awake or asleep when the event occurred?

What was the infant’s body position?

Was the infant alone in the bed?

When was the last time that the infant ate?

Was the infant sick or well in the time before the event?

Is there any history of trauma?

Is there a family history of sudden infant death syndrome or apparent life-threatening event?

* A trick that an emergency physician (EP) can use to help the caregiver answer this question is as follows: (1) the EP asks the caregiver to look at him or her, (2) the EP says “Go,” and (3) the caregiver says “Stop” when he or she thinks that the time that has passed matches the time that the event ended.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

ALTEs and apnea are clinical manifestations that have many causes, as summarized in Box 15.2. The most common organ systems involved (in order of decreasing frequency) are the gastrointestinal, neurologic, respiratory, cardiac, metabolic, and endocrine systems. The cause of ALTE in an individual patient is likely to be discovered only about 50% of the time.

Box 15.2 Causes of Apparent Life-Threatening Events

Diagnostic testing is best guided by the history and physical examination. Laboratory tests have been shown to be contributory to the diagnosis only 3.3% of the time if the results of the history and physical examination were noncontributory.6 An Israeli study concluded that diagnostic testing has low yield in infants with normal perinatal histories and normal findings on physical examination.7

Disposition

Historically it has been the practice that all infants with apnea or ALTE be admitted for observation. Some studies suggest that certain low-risk infant groups might be able to be discharged home from the ED.8,9 Box 15.3 lists low-risk criteria for ALTE. An infant meeting all the criteria in this box would have a very low probability of experiencing an adverse outcome. Otherwise, it is prudent to admit the infant for observation and in-patient evaluation by a pediatric specialist.

Excessive Crying and Irritability

Epidemiology

Crying peaks in infancy at 6 weeks of age with an average crying time of 3 hours per day. More of the crying time is clustered in the late afternoon and evening. Forty percent of these infants cry for 30 minutes or longer at one time, 75% of whom have the longest crying spells between 6 and 12 PM.10 The prevalence of excessive crying varies between 1.5% and 11.9%, depending on the definition of excessive crying.11

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Box 15.4 lists important questions to ask the caregiver of an afebrile infant with excessive crying. Table 15.2 lists possible physical findings in these infants.

Box 15.4 Historical Questions to Ask the Caregiver of an Afebrile Infant with Acute and Excessive Crying

Was the crying gradual or sudden in onset?

How long has the child been crying?

Were there any potential inciting events (trauma, immunizations)?

Has the child been sick or had a fever?

Has any change in feeding pattern or stooling taken place?

Did the infant have any significant birth or perinatal problems?

Table 15.2 Potential Abnormalities in Crying Infants Found on Physical Examination

| FINDINGS AND POSSIBLE DIAGNOSES | |

|---|---|

| Inspection | |

| General | Ill appearance: |

| Sepsis, meningitis, other infectious process | |

| Dehydration | |

| Congenital heart disease (cardiogenic shock), supraventricular tachycardia | |

| Volvulus, bowel perforation, incarcerated hernia, intussusception, appendicitis | |

| Intracranial hemorrhage (traumatic/nontraumatic) | |

| Hypoglycemia, inborn error of metabolism | |

| Skin | Trauma, abscess, cellulitis |

| Eyes, ears, nose, throat | Corneal abrasion, foreign body, teething |

| Abdomen, genitourinary structures | Hernia, hair tourniquet on penis, paraphimosis |

| Extremities/clavicles | Fracture deformity (accidental/nonaccidental), digit hair tourniquet |

| Palpation | |

| Head | Trauma Fontanelle: Dehydration, increased intracranial pressure |

| Chest | Clavicular fracture |

| Abdomen | Tenderness/peritoneal signs: Volvulus, bowel perforation, appendicitis, intussusception, incarcerated hernia |

| Genitourinary structures | Testicular torsion |

| Extremities/clavicles | Trauma, fracture, soft tissue infection |

| Auscultation | |

| Heart | Decreased pulses: Congenital heart disease, septic shock |

| Lungs | Murmur: Congenital heart disease |

| Tachycardia: Supraventricular tachycardia, congestive heart failure | |

| Stridor: Upper airway obstruction | |

| Wheezing: Airway foreign body, bronchiolitis | |

| Rales: Pneumonia, congestive heart failure | |

| Abdomen | Hypoactive/hyperactive or absence of bowel sounds: Volvulus, intussusception, appendicitis, incarcerated hernia |

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

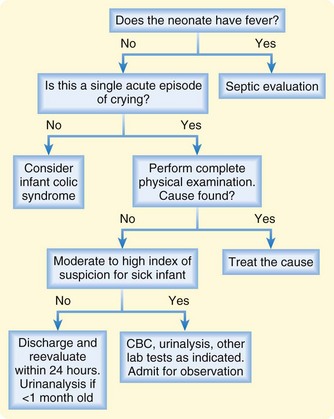

The first differentiation that the clinician must make is whether the child is febrile (see the section “Fever”). In an afebrile infant the chronicity of the crying is important. Is the crying an acute single episode, or has it been an ongoing problem for some time?

The latter describes colic, which affects a large subgroup of excessively crying infants. Classically, colic has been described by the rule of threes—crying for 3 hours per day, for at least 3 days per week, for 3 weeks. Scores of theories concerning the etiology of colic have been proposed; such theories range from physiologic disturbances (cow’s milk allergies, gastrointestinal reflux, hypocontractile gallbladder, and other gastrointestinal disturbances), to infant temperament and maternal response, to deficiencies in parenting practices.12 No single cause has been identified.

No pharmacologic agent has been listed as being both safe and efficacious for the treatment of colic. Anticholinergic agents have been found to be more effective than placebo but are associated with apnea and should not be administered to infants younger than 6 months.13 Many other interventions have been proposed for colic, such as having the infant in a car, specific ways to hold the infant, use of white noise, crib vibrators, and herbal teas. None have been shown to be particularly beneficial, however. The EP should reassure parents that there is no ideal treatment of colic, that their child is normal, that the infant will outgrow the colic, and that colic has no long-term sequelae.

A retrospective study involving 237 afebrile children younger than 1 year brought to the ED with the chief complaint of crying or fussiness revealed that 5.1% had a serious underlying etiology. The final diagnosis in the 237 patients was made by the history and physical examination alone in 66% of cases. Only 0.8% of the diagnoses were made by diagnostic evaluation alone. These authors concluded that afebrile crying infants younger than 1 month should undergo urinalysis.14

A suggested approach to the ED evaluation of an excessively crying child is presented in Figure 15.2.

Cyanosis

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

An easy method of classifying cyanosis is by causative organ system (Box 15.5). The cardiac and respiratory systems are responsible for the large majority of cases of neonatal cyanosis. Distinguishing between these two categories can be difficult but is necessary for optimal management of the patient.

Treatment

If a cyanotic neonate continues to show signs of inadequate tissue oxygenation after the initial resuscitation, prostaglandin E1 (alprostadil) should be given intravenously (IV) starting at 0.05 to 0.1 mcg/kg/min. Administration of prostaglandin is frequently associated with apnea, fever, and occasionally shock. The EP should be prepared to intubate the infant if such complications arise. One study has shown that aminophylline given as a 6-mg/kg bolus before the administration of prostaglandin E1, followed by 2 mg/kg IV every 8 hours for 72 hours, significantly reduces apnea.15

Difficulty Breathing

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

A list of potential causes of respiratory distress that can occur anytime during the first 28 days is presented in Box 15.6. The majority of causes are pulmonary, cardiac, or infectious. Diagnostic testing includes a complete blood count, serum glucose measurement, metabolic profile, blood cultures, arterial blood gas measurements, urinalysis, urine culture, chest radiography, and electrocardiography.

Pneumonia is the most common and most serious infectious cause of respiratory distress in the first 28 days of life. From a clinical perspective, neonatal pneumonia can be divided into early-onset and late-onset types (Table 15.3).

| ONSET OF PNEUMONIA | BACTERIAL CAUSES | VIRAL CAUSES |

|---|---|---|

| Early |

The clinical findings of neonates with pneumonia can be atypical. Signs of respiratory distress are generally present, but they may be absent. Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as vomiting, abdominal distention, and poor feeding, may predominate. General systemic signs such as lethargy, ill appearance, poor feeding, and jaundice may be the initial complaints. The classic radiographic appearance consists of bilateral alveolar densities with air bronchograms.16 Hyperinflation of the lungs without evidence of infiltrate is a common early finding with viral lower respiratory tract infections.17 The chest radiograph may be normal in up to 15% of cases.18

Laryngomalacia is the most common cause of stridor in infants. Stridor secondary to laryngomalacia starts soon after birth and is exacerbated by crying, agitation, and supine positioning. This disorder is generally benign and self-limited. The stridor worsens with upper respiratory tract infections and occasionally necessitates hospital admission for supportive care. Less than 10% of patients with laryngomalacia have significant respiratory or feeding problems that mandate epiglottoplasty or tracheotomy. Vocal cord paralysis is the next most common cause of neonatal stridor19 and can be unilateral or bilateral. Unilateral cord paralysis generally requires conservative treatment, such as monitoring oxygen saturation and observing for aspiration secondary to an incompetent glottis.

See Box 15.7 for the differential diagnosis of stridor in neonates. Inspiratory stridor indicates a lesion above the glottis such as laryngomalacia. Biphasic stridor usually points to a lesion at the level of the glottis or the subglottic area, such as vocal cord paralysis or subglottic stenosis. Expiratory stridor is caused by a lesion below the thoracic inlet, typically tracheomalacia. The stridor may result from a fixed narrowing that is not worsening or from progressive narrowing, which should alert the physician to urgent airway management action. A stridulous infant without severe distress should be examined by the EP. Radiographs of the chest and soft tissues of the neck are indicated. The definitive diagnostic test is direct laryngoscopy by a pediatric otorhinolaryngologist.

Treatment and Disposition

Antibiotic coverage for early-onset pneumonia consists of ampicillin, 150 mg/kg IV every 12 hours if meningitis is suspected. If meningitis is not suspected, 50 to 100 mg/kg IV every 12 hours is adequate. Intravenous gentamicin is given according to gestational age and renal function. For infants born after 35 weeks of gestation, the dose is 4 mg/kg every 24 hours; for those born between 30 and 35 weeks of gestation, the dose is 3 mg/kg every 24 hours.20 In neonates with late-onset neonatal pneumonia, some authorities would recommend administering vancomycin, 15 mg/kg IV every 12 hours with gentamicin, instead of ampicillin until the results of culture are available.21 If herpes simplex virus pneumonia is suspected, acyclovir, 20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours (in infants with normal renal function), should be started.22 All neonates with pneumonia should be admitted to the hospital.

In an infant with cardiovascular collapse from a ductus-dependent left-sided heart obstruction, the only nonoperative way to maintain adequate systemic perfusion is to keep the ductus arteriosus patent. This is done on an emergency basis by the administration of a continuous infusion of prostaglandin E1 (alprostadil). The initial dose is 0.05 to 0.1 mcg/kg/min IV, with a maintenance dose titrated to the lowest dose effective in maintaining patency.23 Treatment of a stridulous infant initially depends on the degree of respiratory distress. If respiratory distress is present, it is best to not manipulate the child too much unless emergency airway interventions are necessary. If possible, the EP should perform the physical examination of a stridulous infant in distress in the presence of an otorhinolaryngologist or pediatric surgeon who can obtain a surgical airway immediately in a controlled setting (operating suite). A neonate with stridor should be admitted to the hospital unless the EP is certain that the child is stable and the cause of the stridor is not progressing.

Fever

Scope

Fever is defined as a rectal temperature of 38° C (100.4° F) or higher. The majority of febrile illnesses in infants are self-limited viral infections. Ten percent to 20% of febrile infants younger than 3 months have a serious bacterial infection (SBI), defined as bacterial meningitis, bacteremia, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, skin or soft tissue infection, bacterial enteritis, septic arthritis, or osteomyelitis. Bacteremia is twice as likely to occur in the first month of life as in the second month.24

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

A febrile neonate may look remarkably well or may be extremely toxic appearing.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Box 15.8 present a work-up for a febrile infant younger than 28 days.

Box 15.8 Septic Work-up for Febrile Infants Younger Than 28 Days

Complete blood count with differential

Urinalysis—catheter or suprapubic

Lumbar puncture—cell count, glucose, protein, Gram stain, cerebrospinal fluid culture, herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction if suspected

Chest radiograph (if symptoms of respiratory infection present)

Stool for white blood cell count, culture, and sensitivity (if diarrhea present)

Recent literature suggests that C-reactive protein levels can predict infection. The limitation to its use is that a period of up to 8 to 10 hours is required for synthesis, so it has a variable range of sensitivity (from 14% to 100%) in the first 24 hours. A cutoff of 70 g/L has been proposed, although it is a nonspecific marker for infection.25 Procalcitonin also deserves mention as a possible marker for SBI. It is the prehormone of calcitonin and increases within 2 hours of an infection. Its sensitivity is 92.6% with a specificity of 97.5% if obtained outside the first 48 hours of life.26

Treatment

Empiric antibiotic treatment of neonatal sepsis consists of either ampicillin and gentamicin or ampicillin and cefotaxime (Boxes 15.9 and 15.10). If neonatal meningitis is suspected, ampicillin and cefotaxime are preferred. Some authorities would add gentamicin as a third antibiotic for suspected meningitis when no organisms are seen on Gram stain of cerebrospinal fluid.27 Herpes simplex virus infection should be strongly considered in febrile infants with seizures and abnormal cerebrospinal fluid results. Skin lesions and abnormal liver function values should further increase suspicion for this disorder. An infant with suspected herpes simplex virus infection should receive acyclovir, 60 mg/kg/day in three divided doses (20 mg/kg per dose). Acyclovir should be continued until the results of herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction are negative. Neonates with an identifiable viral infection (e.g., respiratory syncytial virus) have as high as a 7% chance of having a concomitant SBI.28–31 Therefore, a septic evaluation should be performed in any child 1 to 28 days old with fever despite an identifiable viral infection. Antibiotics should be administered empirically to this group. Febrile neonates should be admitted to the hospital.

Vomiting

Signs and Symptoms

It is important to distinguish between bilious vomiting and nonbilious vomiting. If bilious vomiting is reported, it is assumed to be obstructive and a surgical emergency until proved otherwise. Studies have suggested that 20% to 50% of neonates with bilious emesis within the first week of life have a surgical condition.32

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Causes of vomiting can be divided into anatomic and nonanatomic categories (Box 15-11).

Diarrhea

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Salmonella gastroenteritis is potentially dangerous in neonates because of its association with systemic sepsis. Bacteremia may occur in 30% to 50% of neonates infected with this organism. Diarrhea from Salmonella gastroenteritis is usually watery with mucus and may appear bloody. This organism is an enteroinvasive bacterium (i.e., it invades the intestinal mucosa), so a methylene blue smear of a stool specimen will reveal white blood cells. Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is one of the more dangerous causes of neonatal diarrhea. It is classically seen in premature infants but can occur in term neonates. Its incidence is also higher in infants with congenital heart disease.34 The diarrhea is typically bloody and is associated with other symptoms, such as decreased feeding, vomiting, ileus, and abdominal distention. If not treated, symptoms progress to bradycardia, hypothermia, apnea, hypotension, and death. Diagnostic radiographic findings are pneumatosis intestinalis (air in the bowel wall) and air in the portal vein. Intestinal perforation leads to pneumoperitoneum.

Neonatal Jaundice

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Jaundice can be normal (physiologic) or abnormal (nonphysiologic). Physiologic jaundice usually becomes visible on the second or third day of life. Jaundice in the first 24 hours of life is always abnormal. Physiologic jaundice is thought to be secondary to the higher breakdown of red blood cells in neonates and transient slowing of conjugation processes in the liver. It peaks at levels between 5 and 12 mg/dL on the third or fourth day of life and then starts to decline. Risk factors for higher levels of physiologic hyperbilirubinemia include a family history of neonatal jaundice, breastfeeding, bruising and cephalohematoma, maternal age older than 25 years, Asian ethnicity, prematurity, weight loss, and delayed bowel movement. Box 15.12 lists the criteria for physiologic jaundice.

Box 15.12 Criteria for Physiologic Jaundice

Jaundice occurring after 24 hours of life

Serum bilirubin level rising no faster than 0.5 mg/dL/hr or 5 mg/dL/day

Total bilirubin value not exceeding 15 mg/dL in a term neonate or 10 mg/dL in a preterm neonate

No evidence of acute hemolysis

Jaundice not persisting longer than 10 days in a term neonate or 21 days in a preterm neonate*

Treatment

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has issued practice guidelines for the treatment of neonatal jaundice.35 One tool that the EP may find helpful is the website www.bilitool.org, in which parameters may be entered to determine the infant’s risk based on the bilirubin level obtained. The following information is needed to estimate an infant’s risk: (1) the infant’s date of birth and time (to the hour), (2) the infant’s gestational age, and (3) the time that the bilirubin level was obtained. After entering this information, the AAP guidelines will be listed and appropriate therapy recommendations will be displayed based on the level of risk.

Metabolic Emergencies

Scope

Metabolic emergencies account for a small percentage of disorders in neonates seen in the ED. This low incidence accounts for the difficulty recognizing and treating these emergencies. Adrenal insufficiency is one metabolic emergency in neonates that can be encountered in the ED and should be taken into consideration to reduce an infant’s morbidity and mortality.36

Treatment

The first step is to restore volume with 0.9% NS in 20-mL/kg boluses. Following initial volume replacement,  is administered at 1 to

is administered at 1 to  times the maintenance rate. Cortisol replacement should be achieved by administration of hydrocortisone, 1 to 2 mg/kg IV for term infants and then 25 to 100 mg/m2/day divided into three to four doses every 6 to 8 hours. Hyperkalemia is typically well tolerated and saline is usually all that is needed to lower the potassium level. Intravenous calcium gluconate, β-agonists, insulin, and glucose should be available for any potential cardiac arrhythmias.37

times the maintenance rate. Cortisol replacement should be achieved by administration of hydrocortisone, 1 to 2 mg/kg IV for term infants and then 25 to 100 mg/m2/day divided into three to four doses every 6 to 8 hours. Hyperkalemia is typically well tolerated and saline is usually all that is needed to lower the potassium level. Intravenous calcium gluconate, β-agonists, insulin, and glucose should be available for any potential cardiac arrhythmias.37

Brand DA, Altman EI, Purtill R, et al. Yield of diagnostic testing in infants who have had an apparent life-threatening event. Pediatrics. 2005;115:885–893.

Freedman S, Al-Harthy N, Thull-Freedman J. The crying infant: diagnostic testing and frequency of serious underlying disease. Pediatrics. 2009;123:841.

1 Xu J, Kochanek K, Murphy SL, et al. Deaths: final data for 2007. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58(19):6, 9.

2 Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U, Hof D, Peglow UP, et al. Epidemiology of apparent life threatening events. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:297.

3 Little G, Ballard R, Brooks J, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on Infantile Apnea and Home Monitoring. September 29 to October 1, 1986. Pediatrics. 1987;79:292–299.

4 Baird T. Clinical correlates, natural history and outcome of neonatal apnoea. Semin Neonatol. 2004;9:205–211.

5 Stratton S, Taves A, Lewis RJ, et al. Apparent life-threatening events in infants: high risk in the out-of-hospital environment. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:711–717.

6 Brand DA, Altman EI, Purtill R, et al. Yield of diagnostic testing in infants who have had an apparent life-threatening event. Pediatrics. 2005;115:885–893.

7 Weiss K, Fattal-Valevski A, Reif S. How to evaluate the child presenting with an apparent life-threatening event? Isr Med Assoc J. 2010;12:154.

8 Al Khushi N, Côté A. Apparent life-threatening events: assessment, risks, reality. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2011;12:123–132.

9 Claudius I, Keens T. Do all infants with apparent life-threatening events need to be admitted? Pediatrics. 2007;119:679.

10 Michelsson K, Rinne A, Paajanen S. Crying, feeding and sleeping patterns in 1 to 12 month old infants. Child Care Health Dev. 1990;16:99–111.

11 Reijneveld S, Brugman E, Hirasing R. Excessive infant crying: the impact of varying definitions. Pediatrics. 2001;108:893.

12 Long T. Excessive infantile crying: a review of the literature. J Child Health Care. 2001;5:111–116.

13 Lucassen P, Assendelft WJ, Gubbels JW, et al. Effectiveness of treatments for infantile colic: systematic review. BMJ. 1998;316:1563–1569.

14 Freedman S, Al-Harthy N, Thull-Freedman J. The crying infant: diagnostic testing and frequency of serious underlying disease. Pediatrics. 2009;123:841.

15 Lim D, Kulik TJ, Dim DW. Aminophylline for the prevention of apnea during prostaglandin E1 infusion. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e27–e29.

16 Haney P, Bohlman M, Sun C. Radiographic findings in neonatal pneumonia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143:23–26.

17 Bramson R, Griscom N, Cleveland R. Interpretation of chest radiographs in infants with cough and fever. Radiology. 2005;236:22.

18 Mathur N, Garg K, Kumar S. Respiratory distress in neonates with special reference to pneumonia. Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:529–537.

19 Mancuso R. Stridor in neonates. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996;43:1339–1356.

20 Hansen A, Forbes P, Arnold A, et al. Once-daily gentamicin dosing for the preterm and term newborn: proposal for a simple regimen that achieves target levels. J Perinatol. 2003;23:635–639.

21 Speer ME. Neonatal pneumonia. UpToDate. 2010.

22 Pickering L. Red book: 2003 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 26th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2003.

23 Schamberger M. Cardiac emergencies in children. Pediatr Ann. 1996;25:339–344.

24 Berman S. Acute fever in infants younger than three months. In: Pediatric decision making, 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2003.

25 Blommendahl J, Janas M, Laine S, et al. Comparison of procalcitonin with CRP and differential white blood cell count for diagnosis of culture-proven neonatal sepsis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:620–622.

26 Gómez B, Mintegi S, Benito J, et al. Blood culture and bacteremia predictors in infants less than three months of age with fever without source. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:43.

27 Byington C, Rittichier KK, Bassett KE, et al. Serious bacterial infections in febrile infants younger than 90 days of age: the importance of ampicillin-resistant pathogens. Pediatrics. 2003;111:964–968.

28 Byington C, Enriquez FR, Hoff C, et al. Serious bacterial infections in febrile infants 1 to 90 days old with and without viral infections. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1662–1666.

29 Melendez E, Harper M. Utility of sepsis evaluation in infants 90 days of age or younger with fever and clinical bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:1053–1056.

30 Antonow J, Hansen K, McKinstry CA, et al. Sepsis evaluations in hospitalized infants with bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:231–236.

31 Levine D, Platt SL, Dayan PS, et al. Risk of serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants with respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1728–1734.

32 Godbole P, Stringer M. Bilious vomiting in the newborn: how often is it pathologic? J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:909–911.

33 Swischuk L. Acute-onset vomiting in a 15-day-old infant. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1992;8:359.

34 McElhinney D, Hedrick HL, Bush DM. Necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates with congenital heart disease: risk factors and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1080–1087.

35 American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia. Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 2004;114:297–316.

36 Shulman DI, Palmert MR, Kemp SF. Lawson Wilkins Drug and Therapeutics Committee. Adrenal insufficiency: still a cause of morbidity and death in childhood. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e484–e494.

37 Baren J, Rothrock S. Pediatric emergency medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.